Malaria Preventive Practices among People Residing in Different Malaria-Endemic Settings in a Township of Myanmar: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

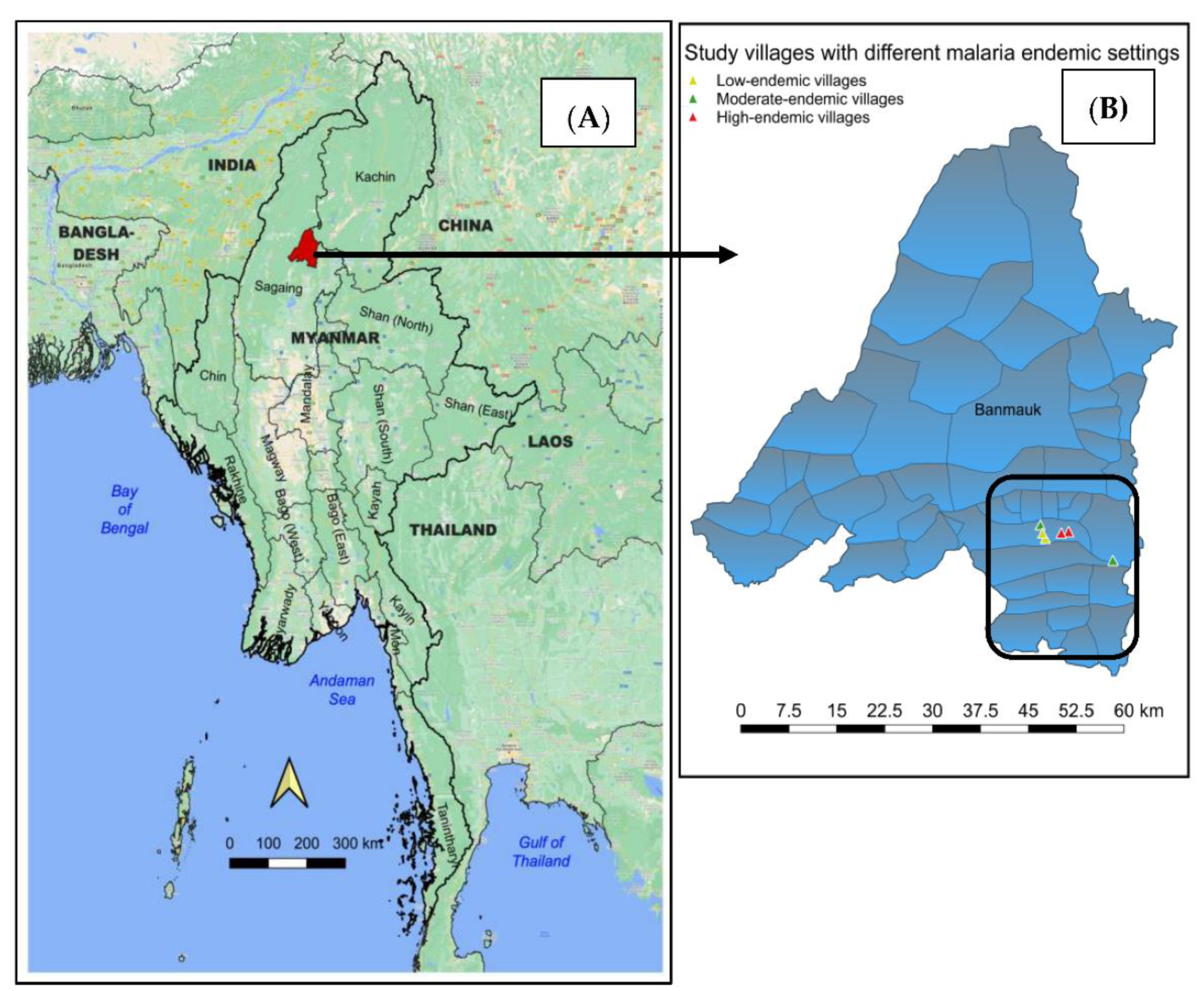

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Subjects

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Findings from the Quantitative Component

3.1.1. General Characteristics of the Respondents

3.1.2. Knowledge on the Causation of Malaria and Access to Malaria-Related Health Information

3.1.3. Malaria Preventive Practices among Respondents from Each Malaria-Endemic Setting

3.1.4. Overall Malaria Preventive Practices in Each Malaria-Endemic Setting

3.1.5. Factors Associated with Poor Malaria Preventive Practices among People Residing in Low-, Moderate-, and High-Malaria-Endemic Villages

3.2. Findings from the Qualitative Components

3.2.1. Perspectives on the Current Malaria Situation

“In my family, my son passed away due to malaria in the last five years when malaria was very common in this village. Nowadays, we can easily receive a diagnosis of malaria and quality antimalarial drugs when malaria is detected. Still, many malaria cases are reported especially during rainy season.”(IDI, 35-year-old man)

“Malaria was very serious in the old days. When one family member contracted malaria, other people had to take care of the patient which could lead to reduced family income. To date, malaria remains a health problem in our village, and we are taking good care to prevent it.”(IDI, 28-year-old woman)

“In my family, everyone contracted malaria two to three times already. Healthcare providers and village malaria volunteers are always ready to provide diagnostic and treatment services. Nonetheless, we still want more malaria-related health information whenever possible.”(IDI, 31-year-old man)

3.2.2. Challenges Faced by Respondents Adhering to Malaria Preventive Measures Including LLIN Use

“I am aware that malaria is transmitted by biting mosquitos. Therefore, I always use bed nets either conventional or insecticidal nets when I am sleeping. Moreover, I also avoid eating bananas and drinking stream water when travelling in the forest.”(IDI, 27-year-old man)

“In our family, we have several insecticidal nets distributed by malaria officers. Nevertheless, I am a gold miner working in the forest especially during night-time, so using LLINs is not possible. Therefore, I just wear long-sleeved clothes to prevent biting of mosquitos and other insects.”(IDI, 35-year-old man)

“In my family, we have used LLINs especially during nighttime. As for me, I prefer to use conventional ones which use a thick layer nylon net. Still, we have some new LLINs which are kept for visitors if any.”(IDI, 35-year-old woman)

3.2.3. Perceived Possible Solutions to Overcome the Obstacles towards the Prevention of Malaria

“I am willing to use LLIN whenever and wherever I am sleeping. Nonetheless, as I work and reside in the farm, I could not use any net. However, I burned rubbish or used mosquito coils to prevent mosquito bites. If possible, I do want any kind of mosquito repellent provided by the malaria project.”(IDI, 29-year-old man)

“We usually use mosquito nets or LLINs at night when many mosquitoes emerged. Still, we burn mosquito coils to prevent mosquito bites before sleeping. Therefore, it would be useful if we could receive mosquito repellents especially for young children.”(IDI, 42-year-old woman)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2021 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Malaria Consortium. Consultancy Report–Assessment of Malaria Surveillance in Myanmar. Available online: https://www.malariaconsortium.org/media-downloads/325/Assessment%20of%20Malaria%20Surveillance%20in%20Myanmar (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Suwonkerd, W.; Ritthison, W.; Ngo, C.T.; Tainchum, K.; Bangs, M.J.; Chareonviriyaphap, T. Vector biology and malaria transmission in Southeast Asia. In Anopheles Mosquitoes-New Insights into Malaria Vectors; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/45385 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Chaumeau, V.; Cerqueira, D.; Zadrozny, J.; Kittiphanakun, P.; Andolina, C.; Chareonviriyaphap, T.; Nosten, F.; Corbel, V. Insecticide resistance in malaria vectors along the Thailand-Myanmar border. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hasyim, H.; Dale, P.; Groneberg, D.A.; Kuch, U.; Müller, R. Social determinants of malaria in an endemic area of Indonesia. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenker, H.; Keating, J.; Alilio, M.; Acosta, A.; Lynch, M.; Nafo-Traore, F. Strategic roles for behavior change communication in a changing malaria landscape. Malar. J. 2014, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ipa, M.; Widawati, M.; Laksono, A.D.; Kusrini, I.; Dhewantara, P.W. Variation of preventive practices and its association with malaria infection in eastern Indonesia: Findings from a community-based survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maung, T.M.; Oo, T.; Wai, K.T.; Hlaing, T.; Owiti, P.; Kumar, B.; Shewade, H.D.; Zachariah, R.; Thi, A. Assessment of household ownership of bed nets in areas with and without artemisinin resistance containment measures in Myanmar. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2018, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lengeler, C. Insecticide-Treated Nets for Malaria Control: Real Gains. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004, 82, 84. Available online: http://www.scielosp.org/pdf/bwho/v82n2/v82n2a03.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Maung, T.M.; Tripathy, J.P.; Oo, T.; Oo, S.M.; Soe, T.N.; Thi, A.; Wai, K.T. Household ownership and utilization of insecticide-treated nets under the Regional Artemisinin Resistance Initiative in Myanmar. Trop. Med. Health 2018, 46, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Min, K.T.; Maung, T.M.; Oo, M.M.; Oo, T.; Lin, Z.; Thi, A.; Tripathy, J.P. Utilization of insecticide-treated bed nets and care-seeking for fever and its associated socio-demographic and geographical factors among under-five children in different regions: Evidence from the Myanmar Demographic and Health Survey, 2015–2016. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, S.Y.; Maung, T.M.; Tripathy, J.P.; Shewade, H.D.; Oo, S.M.; Linn, Z.; Thi, A. Barriers in distribution, ownership, and utilization of insecticide-treated mosquito nets among migrant population in Myanmar, 2016: A mixed-methods study. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Myanmar Demographic and Health Survey (2015–2016); MOH: NayPyiTaw, Myanmar. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR324/FR324.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Nyunt, M.-H.; Aye, K.M.; Kyaw, M.P.; Kyaw, T.T.; Hlaing, T.; Oo, K.; Zaw, N.N.; Aye, T.T.; San, N.A. Challenges in universal coverage and utilization of insecticide-treated bed nets in migrant plantation workers in Myanmar. Malar. J. 2014, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pooseesod, K.; Parker, D.M.; Meemon, N.; Lawpoolsri, S.; Singhasivanon, P.; Sattabongkot, J.; Cui, L.; Phuanukoonnon, S. Ownership and utilization of bed nets and reasons for use or non-use of bed nets among community members at risk of malaria along the Thai Myanmar border. Malar. J. 2021, 20, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naing, P.A.; Maung, T.M.; Tripathy, J.P.; Oo, T.; Wai, K.T.; Thi, A. Awareness of malaria and treatment-seeking behavior among persons with acute undifferentiated fever in the endemic regions of Myanmar. Trop. Med. Health 2017, 45, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parker, D.M.; Carrara, V.I.; Pukrittayakamee, S.; McGready, R.; Nosten, F.H. Malaria ecology along the Thailand–Myanmar border. Malar. J. 2015, 14, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aung, P.L.; Soe, M.T.; Oo, T.L.; Aung, K.T.; Lin, K.K.; Thi, A.; Menezes, L.; Parker, D.M.; Cui, L.; Kyaw, M.P. Spatiotemporal dynamics of malaria in Banmauk Township, Sagaing region of Northern Myanmar: Characteristics, trends, and risk factors. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 653. [Google Scholar]

- National Malaria Control Program. Myanmar Malaria Indicator Survey; Myanmar NMCP: NayPyiTaw, Myanmar, 2015; Available online: https://www.malariaconsortium.org/what-we-do/projects/46/myanmar-malaria-indicator-survey (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Aung, P.L.; Pumpaibool, T.; Soe, T.N.; Kyaw, M.P. Knowledge, attitude, and practice levels regarding malaria among people living in the malaria-endemic area of Myanmar. J. Health Res. 2019, 34, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindjet Mindmanager. Available online: https://www.mindjet.com/mindmanager (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Aung, Y.K.; Zin, S.S.; Tesfazghi, K.; Paudel, M.; Thet, M.M.; Thein, S.T. A comparison of malaria prevention behaviors, care-seeking practices and barriers between malaria at-risk worksite migrant workers and villagers in Northern Shan State, Myanmar—A mixed method study. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyunt, M.H.; Aye, K.M.; Naing, S.T.; Mon, A.S.; Htwe, M.M.; Win, S.M.; Thwe, W.M.; Zaw, N.N.; Kyaw, M.P.; Thi, A. Residual malaria among migrant workers in Myanmar: Why still persistent and how to eliminate it? BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyawt, S.K.; Pearson, A. Knowledge, attitudes and practices with regard to malaria control in an endemic rural area of Myanmar. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2004, 35, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, P.L.; Pumpaibool, T.; Soe, T.N.; Burgess, J.; Menezes, L.J.; Kyaw, M.P.; Cui, L. Health education through mass media announcements by loudspeakers about malaria care: Prevention and practice among people living in a malaria endemic area of northern Myanmar. Malar J. 2019, 18, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Htoo, S.N.; Mhote, N.P.P.; Davison, C.M. Association between biological sex and insecticide-treated net use among household members in ethnic minority and internally displaced populations in eastern Myanmar. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanabouasy, C.; Pumpaibool, T.; Kanchanakhan, N. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice regarding malaria prevention towards population in Paksong District Champasack Province, Lao PDR. J. Health Res. 2009, 23, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Than, W.P.; Oo, T.; Wai, K.T.; Thi, A.; Owiti, P.; Kumar, B.; Shewade, H.D.; Zachariah, R. Knowledge, access and utilization of bed-nets among stable and seasonal migrants in an artemisinin resistance containment area of Myanmar. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2017, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linn, N.Y.Y.; Kathirvel, S.; Das, M.; Thapa, B.; Rahman, M.; Maung, T.M.; Kyaw, A.M.M.; Thi, A.; Lin, Z. Are village health volunteers as good as basic health staffs in providing malaria care? A country wide analysis from Myanmar, 2015. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Canavati, S.E.; Kelly, G.C.; Vo, T.H.; Tran, L.K.; Ngo, T.D.; Tran, D.T.; Edgel, K.A.; Martin, N.J. Mosquito net ownership, utilization, and preferences among mobile and migrant populations sleeping in forests and farms in central Vietnam: A cross-sectional study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1917–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlaing, T.; Wai, K.T.; Oo, T.; Sint, N.; Min, T.; Myar, S.; Lon, K.N.; Naing, M.M.; Tun, T.T.; Maung, N.L.Y.; et al. Mobility dynamics of migrant workers and their socio-behavioral parameters related to malaria in Tier II, artemisinin resistance containment zone, Myanmar. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhong, D.; Aung, P.L.; Mya, M.M.; Wang, X.; Qin, Q.; Soe, M.T.; Zhou, G.; Kyaw, M.P.; Sattabongkot, J.; Cui, L.; et al. Community structure and insecticide resistance of malaria vectors in northern-central Myanmar. Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Low-Endemic (n = 120) | Moderate-Endemic (n = 120) | High-Endemic (n = 120) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.833 | |||

| 18–30 | 35 (29.2) | 40 (33.4) | 42 (35.0) | |

| >30–45 | 50 (41.6) | 43 (35.8) | 43 (35.8) | |

| >45 | 35 (29.2) | 37 (30.8) | 35 (29.2) | |

| Gender | 0.620 | |||

| Female | 64 (53.3) | 65 (54.2) | 58 (48.3) | |

| Male | 56 (46.7) | 55 (45.8) | 62 (51.7) | |

| Occupation | 0.773 | |||

| Unemployed | 21 (17.5) | 17 (14.2) | 24 (20.0) | |

| Farmers | 56 (46.7) | 52 (43.3) | 56 (46.6) | |

| Gold miners | 32 (26.7) | 38 (31.7) | 32 (26.7) | |

| Others | 11 (9.1) | 13 (10.8) | 8 (6.7) | |

| Education | 0.769 | |||

| Illiterate | 18 (15.0) | 20 (16.7) | 20 (16.7) | |

| Primary school | 56 (46.7) | 67 (55.8) | 61 (50.8) | |

| Middle school | 34 (28.3) | 25 (20.8) | 29 (24.2) | |

| High school and above | 12 (10.0) | 8 (6.7) | 10 (8.3) | |

| Family members | 0.314 | |||

| <3 | 22 (18.3) | 18 (15.0) | 15 (12.5) | |

| 3–5 | 45 (37.5) | 51 (42.5) | 61 (50.8) | |

| >5 | 53 (44.2) | 51 (42.5) | 44 (36.7) | |

| Annual family income (MMK) a | 0.372 | |||

| <1,000,000 | 36 (30.0) | 44 (36.7) | 31 (25.8) | |

| 1,000,000–2,000,000 | 61 (50.8) | 58 (48.3) | 70 (58.4) | |

| >2,000,000 | 23 (19.2) | 18 (15.0) | 19 (15.8) |

| Statement | Low-Endemic (n = 120) | Moderate-Endemic (n = 120) | High-Endemic (n = 120) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| What is the causation of malaria? | ||||

| Biting of mosquito carrying infected malaria parasites | 100 (83.3) | 89 (74.2) | 91 (75.8) | 0.191 |

| Eating fruits such as banana, papaya or other fruits a | 11 (9.2) | 31 (25.8) | 23 (19.2) | 0.003 * |

| Drinking stagnant water a | 42 (35.0) | 52 (43.3) | 61 (50.8) | 0.046 * |

| Living or sleeping in the forest a | 31 (25.8) | 41 (34.2) | 43 (35.8) | 0.205 |

| Relapse of malaria due to latent parasites in the human body | 20 (16.7) | 21 (17.5) | 23 (19.2) | 0.875 |

| Access to malaria-related health information | ||||

| Have you ever received malaria-related health information? | 82 (68.3) | 76 (63.3) | 89 (74.2) | 0.194 |

| What is the source of information? | 0.202 | |||

| Health care providers (government basic health staff) | 62 (75.6) | 71 (93.4) | 80 (89.9) | |

| Village malaria volunteers | 58 (70.7) | 58 (76.3) | 67 (75.3) | |

| Other stakeholders/ village authorities | 4 (4.9) | 7 (9.2) | 16 (18.0) | |

| How many times have you received it? | 0.624 | |||

| 1–2 | 46 (56.1) | 45 (59.2) | 52 (58.4) | |

| 3–4 | 32 (39.0) | 23 (30.3) | 30 (33.7) | |

| ≥5 | 4 (4.9) | 8 (10.5) | 7 (7.9) | |

| Have you ever received malaria preventive practice-related information? | 61 (50.8) | 68 (56.7) | 72 (60.0) | 0.351 |

| What is the source of information? | 0.351 | |||

| Health care providers (Government basic health staff) | 58 (95.1) | 58 (85.3) | 68 (94.4) | |

| Village malaria volunteers | 34 (55.7) | 24 (35.3) | 30 (41.7) | |

| Other stakeholders/ village authorities | 1 (1.6) | 5 (7.4) | 5 (6.9) | |

| How many times have you ever received it? | 0.630 | |||

| 1–2 | 45 (73.8) | 52 (76.5) | 50 (69.4) | |

| 3–4 | 13 (21.3) | 10 (14.7) | 14 (19.4) | |

| ≥5 | 3 (4.9) | 6 (8.8) | 8 (11.1) | |

| Statement | Low-Endemic (n = 120) | Moderate-Endemic (n = 120) | High-Endemic (n = 120) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| What malaria preventive practices (methods) are you currently following? | |||

| Use of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets | 105 (87.5) | 76 (63.3) | 67 (55.8) |

| Use of conventional bed nets | 15 (12.5) | 34 (28.3) | 41 (34.2) |

| Avoid eating banana, papaya or other fruits a | 13 (10.8) | 12 (10.0) | 18 (15.0) |

| Avoid drinking stagnant water a | 67 (55.8) | 80 (66.7) | 76 (63.3) |

| Personal protective measures (wearing long-sleeved shirts or pants, applying mosquito repellents) | 32 (26.7) | 41 (34.2) | 41 (34.2) |

| Burning rubbish or mosquito coils a | 51 (42.5) | 68 (56.7) | 70 (58.3) |

| Practice regarding long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs) | |||

| Did you sleep under LLINs last night before the survey? | 104 (86.7) | 71 (59.2) | 60 (50.0) |

| Is an average of one LLIN per two individuals sufficient for your family? | 118 (98.3) | 114 (95.0) | 117 (97.5) |

| Did you receive LLINs within the last two years? | 117 (97.5) | 111 (92.5) | 116 (96.7) |

| Have you already washed this current using LLINs more than 20 times? a | 22 (18.3) | 31 (25.8) | 40 (33.3) |

| Characteristic | Moderate-Endemic (n = 120) | High-Endemic (n = 120) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Practice n (%) | Good Practice n (%) | cOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | Poor Practice n (%) | Good Practice n (%) | cOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18–30 | 18 (45.0) | 22 (55.0) | 3.0 (1.2–8.1) | 3.1 (1.3–8.6) | 24 (57.1) | 18 (42.9) | 2.9 (1.1–7.4) | 2.9 (1.4–8.1) |

| >30–45 | 20 (46.5) | 23 (53.5) | 3.2 (1.2–8.5) | 3.4 (1.5–9.1) | 24 (55.8) | 19 (44.2) | 2.8 (1.1–7.0) | 2.8 (1.6–11.0) |

| >45 | 8 (21.6) | 29 (78.4) | Ref. | Ref. | 11 (31.4) | 24 (68.6) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 18 (27.7) | 47 (72.3) | Ref. | Ref. | 20 (34.5) | 38 (65.5) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Male | 28 (50.9) | 27 (49.1) | 2.7 (1.3–5.8) | 3.1 (2.0–8.2) | 39 (62.9) | 23 (37.1) | 3.2 (1.5–6.8) | 3.6 (2.0–9.7) |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 3 (17.6) | 14 (82.4) | Ref. | Ref. | 7 (29.2) | 17 (70.8) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Farmers | 24 (46.2) | 28 (53.8) | 4.0 (1.0–15.6) | 4.1 (1.0–16.1) | 32 (57.1) | 24 (42.9) | 3.2 (1.2–9.0) | 3.5 (1.9–11.2) |

| Gold miners | 18 (47.4) | 20 (52.6) | 4.2 (1.0–17.0) | 4.2 (1.5–19.5) | 17 (53.1) | 15 (46.9) | 2.8 (1.0–8.4) | 2.9 (1.6–10.0) |

| Others | 1 (7.7) | 12 (92.3) | 0.4 (0.0–4.3) | 0.4 (0.1–4.4) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 1.5 (0.3–7.8) | 1.4 (0.2–6.7) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Illiterate | 9 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) | 5.7 (0.6–55.6) | 6.1 (0.9–57.6) | 9 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) | 1.9 (0.4–9.6) | 2.0 (0.8–11.2) |

| Primary school | 30 (44.8) | 37 (55.2) | 5.7 (0.7–48.7) | 5.5 (0.2–44.3) | 38 (62.3) | 23 (37.7) | 3.9 (0.9–16.4) | 3.7 (0.8–15.6) |

| Middle school | 6 (24.0) | 19 (76.0) | 2.2 (0.2–21.8) | 2.2 (0.3–20.8) | 9 (31.0) | 20 (69.0) | 1.1 (0.2–5.0) | 1.1 (0.1–4.3) |

| High school and above | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | Ref. | Ref. | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Family members | ||||||||

| <3 | 6 (33.3) | 12 (66.7) | Ref. | Ref. | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.5) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 3–5 | 19 (37.3) | 32 (62.7) | 1.2 (0.4–3.7) | 1.5 (0.8–4.1) | 31 (50.8) | 30 (49.2) | 1.2 (0.4–3.7) | 1.2 (0.3–3.1) |

| >5 | 21 (41.2) | 30 (58.8) | 1.4 (0.5–4.3) | 1.4 (0.4–3.9) | 21 (47.7) | 23 (52.3) | 1.0 (0.3–3.4) | 0.8 (0.1–2.1) |

| Annual family income (MMK) a | ||||||||

| <1,000,000 | 20 (45.5) | 24 (54.5) | 4.2 (1.1–16.5) | 4.7 (1.7–20.2) | 18 (58.1) | 13 (41.9) | 3.9 (1.1–13.5) | 5.0 (2.0–17.5) |

| 1,000,000–2,000,000 | 23 (39.7) | 35 (60.3) | 3.3 (0.9–12.6) | 4.1 (1.6–14.7) | 36 (51.4) | 34 (48.6) | 3.0 (0.9–9.2) | 3.9 (2.1–11.3) |

| >2,000,000 | 3 (16.7) | 15 (83.3) | Ref. | Ref. | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | Ref. | Ref. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aung, P.L.; Win, K.M.; Pumpaibool, T. Malaria Preventive Practices among People Residing in Different Malaria-Endemic Settings in a Township of Myanmar: A Mixed-Methods Study. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7110353

Aung PL, Win KM, Pumpaibool T. Malaria Preventive Practices among People Residing in Different Malaria-Endemic Settings in a Township of Myanmar: A Mixed-Methods Study. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2022; 7(11):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7110353

Chicago/Turabian StyleAung, Pyae Linn, Kyawt Mon Win, and Tepanata Pumpaibool. 2022. "Malaria Preventive Practices among People Residing in Different Malaria-Endemic Settings in a Township of Myanmar: A Mixed-Methods Study" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 7, no. 11: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7110353

APA StyleAung, P. L., Win, K. M., & Pumpaibool, T. (2022). Malaria Preventive Practices among People Residing in Different Malaria-Endemic Settings in a Township of Myanmar: A Mixed-Methods Study. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 7(11), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7110353