Morphing Quadrotors: Enhancing Versatility and Adaptability in Drone Applications—A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Morphing Mechanics and Actuation

2.1. Overview of Morphing Mechanics in Quadrotors

2.2. Morphing Concepts

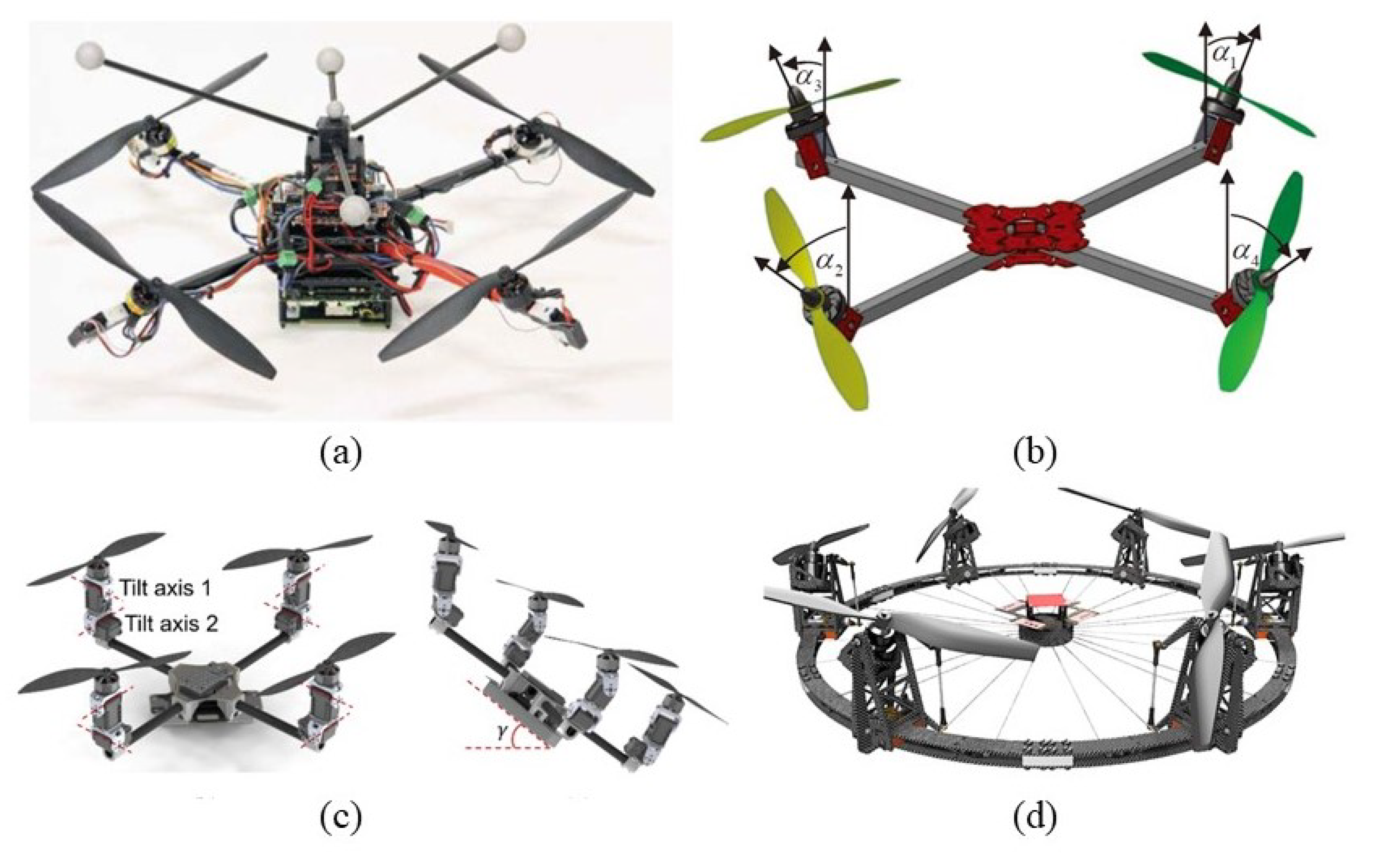

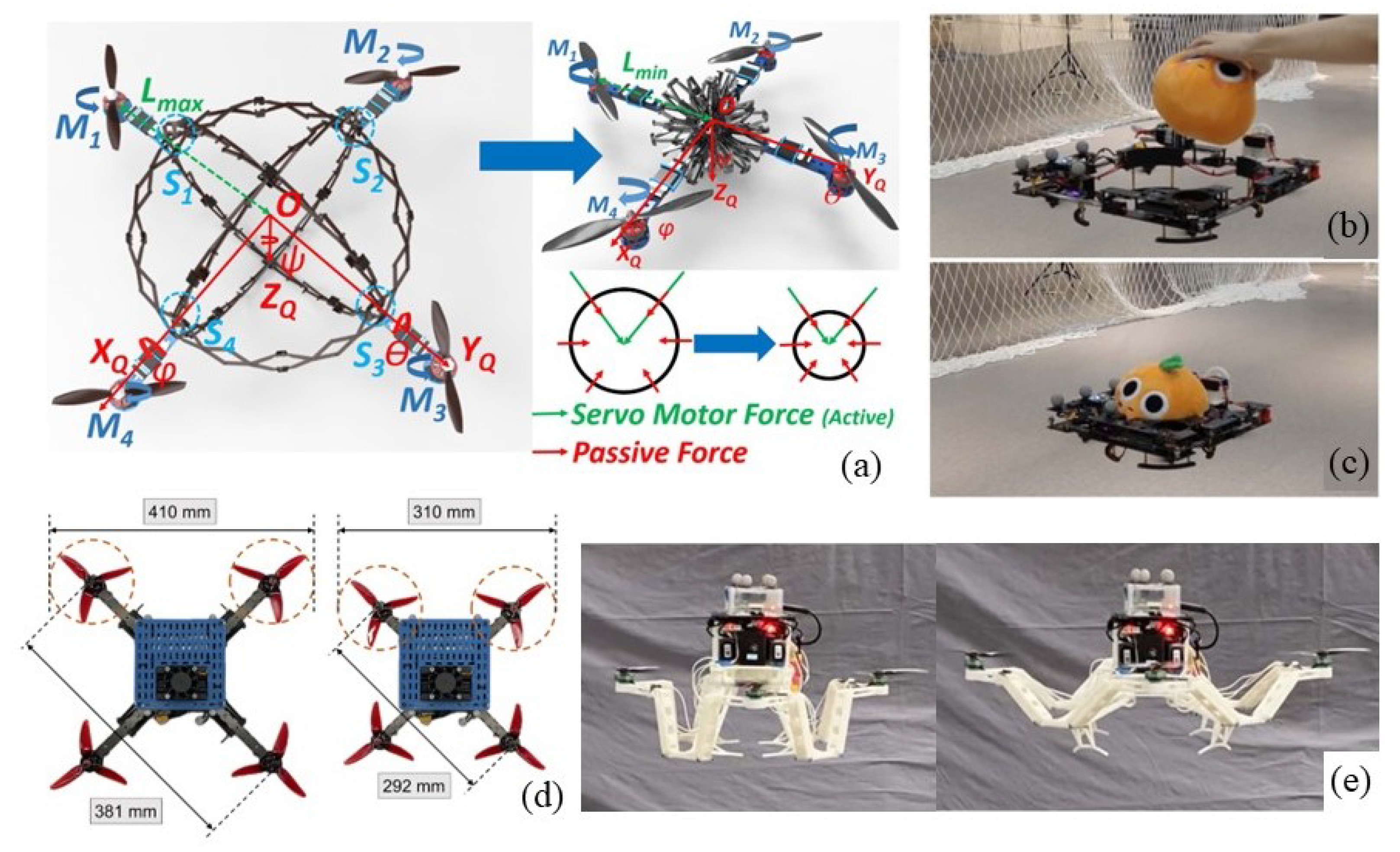

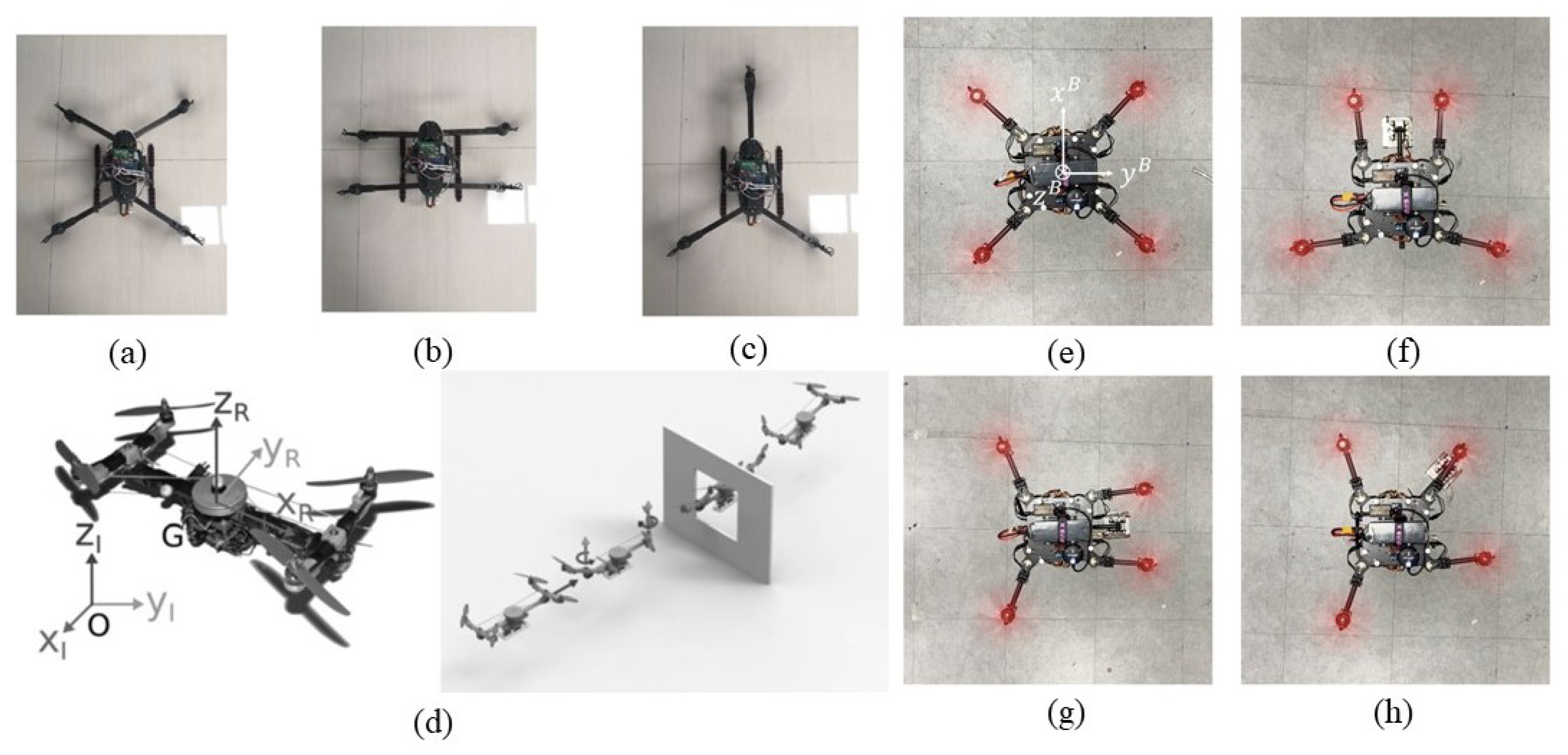

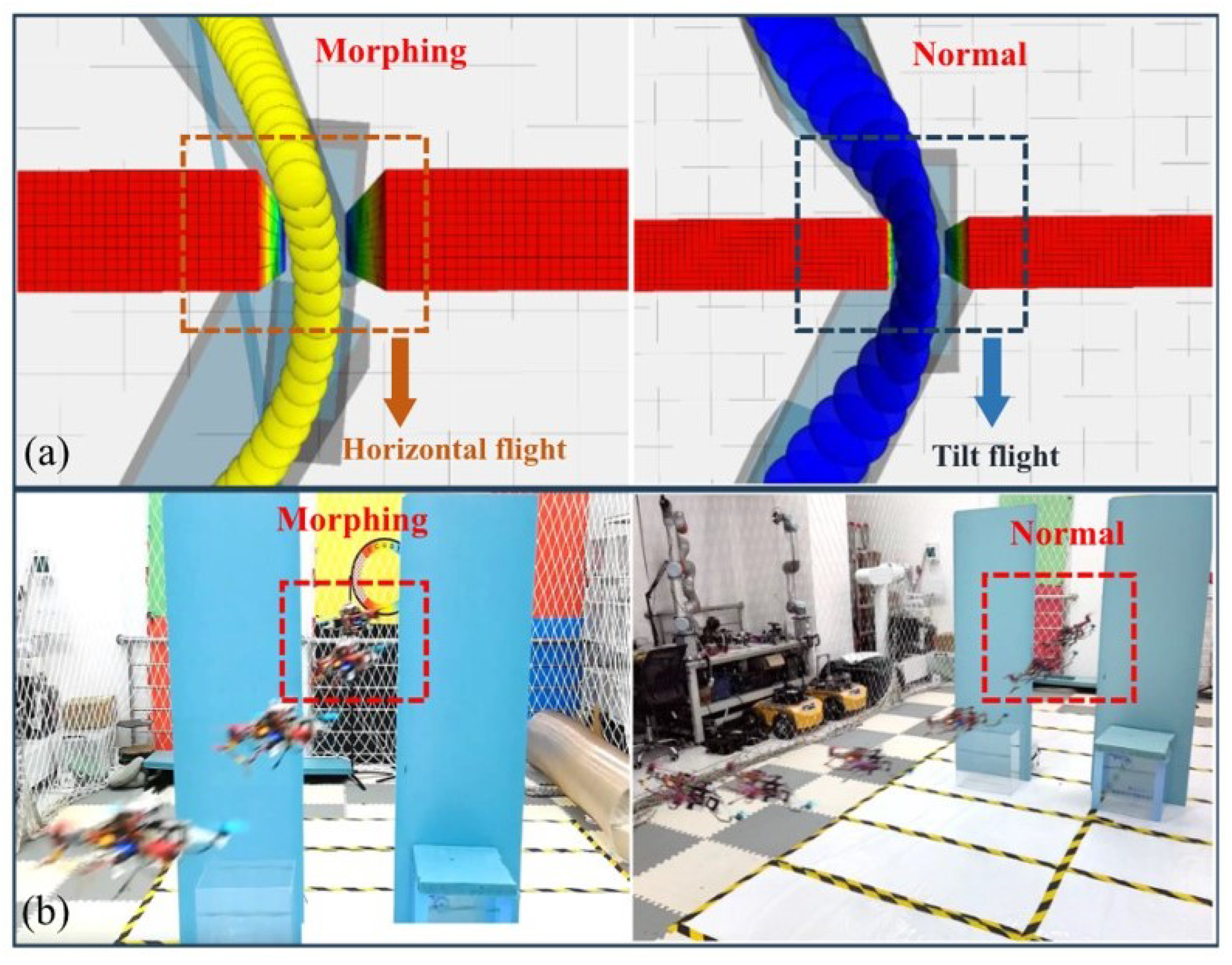

2.2.1. In-Plane Morphing

2.2.2. Out-of-Plane Morphing

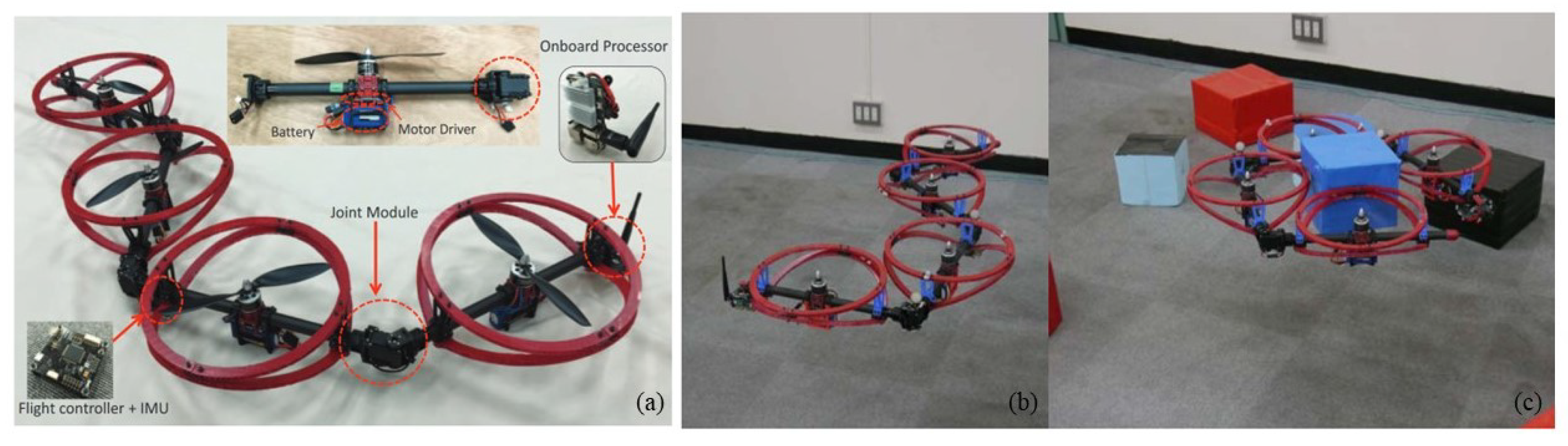

2.2.3. Other Concepts for Enhanced Functionality

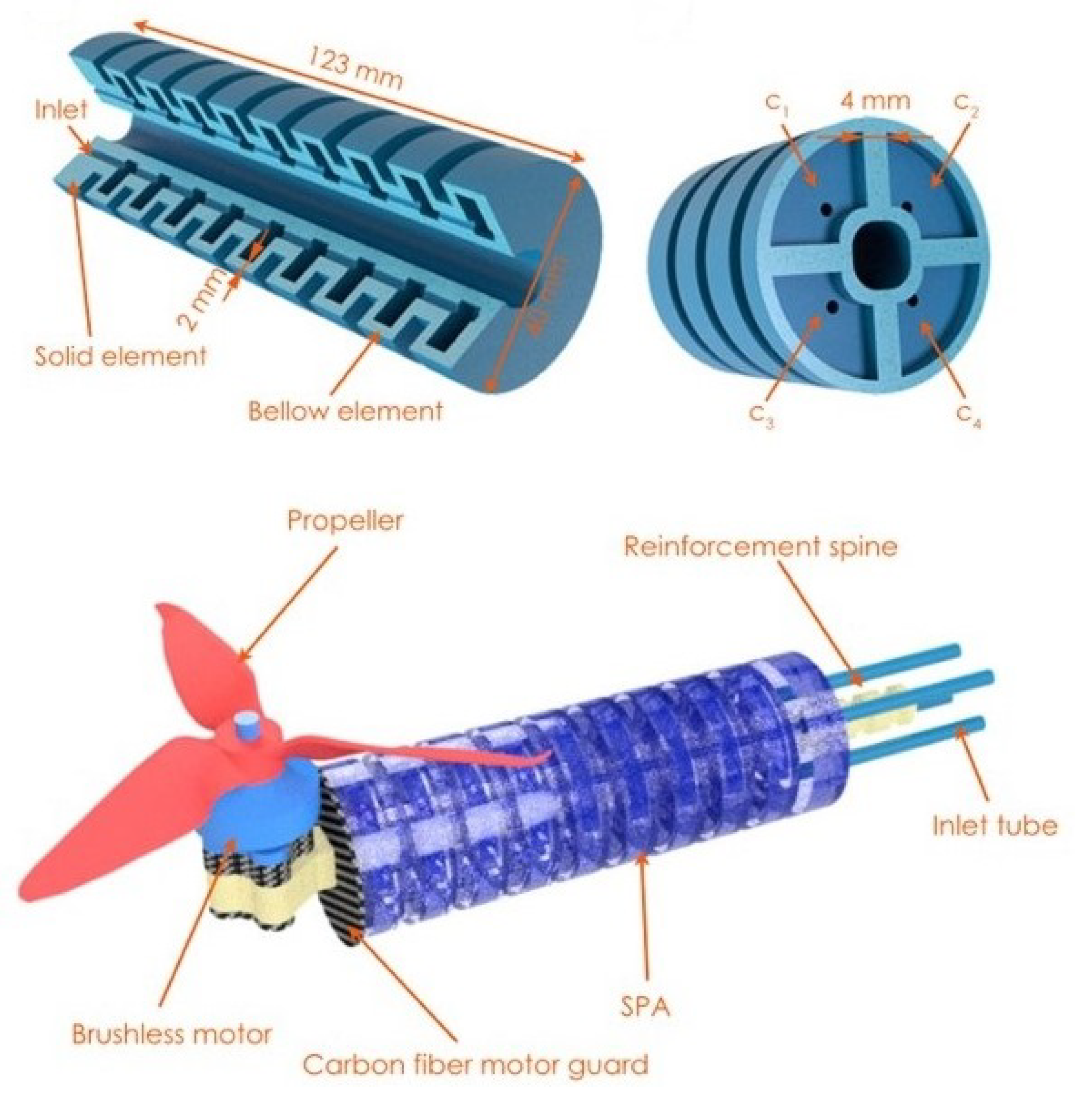

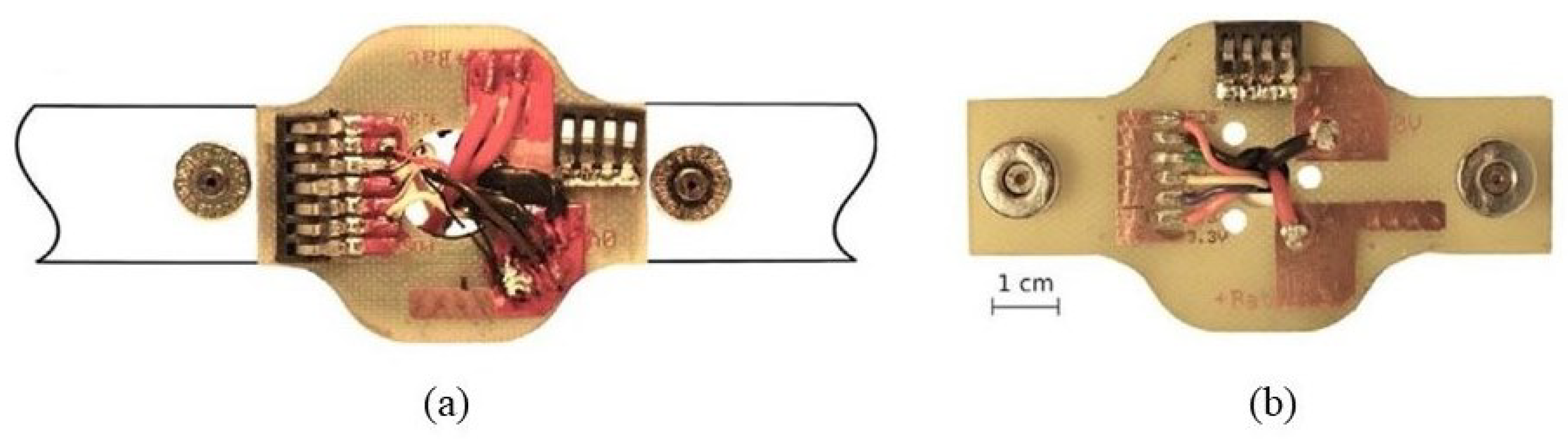

2.3. Actuation Mechanisms

2.3.1. Types of Actuators

2.3.2. Integration with Structural Components

3. Control Strategies

3.1. Modeling and Challenges in Controlling Morphing Quadrotors

3.2. Morphing Quadrotor Control Methods

3.2.1. Adaptive and Robust Control Methods

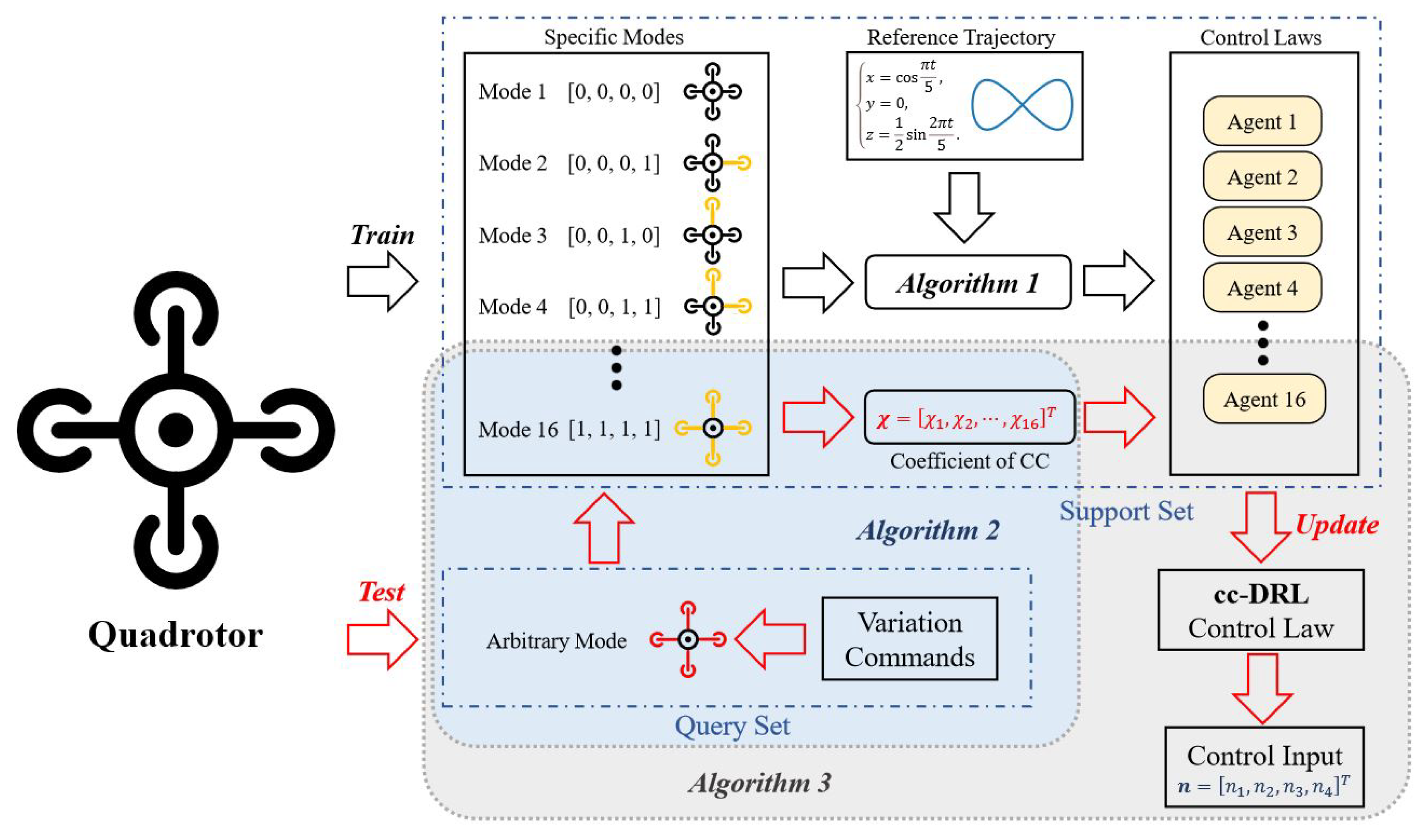

3.2.2. Machine Learning Approaches

3.3. Motion Planning and Trajectory Generation

4. Challenges and Opportunities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | Actuators and Morphing Concept | Design Feature | Control Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Falanga et al. (2019) [14] | 4 servo motors; in-plane morphing; weighs 580 g and spans 47 cm tip-to-tip in diagonal configuration | Capable of transitioning between “X”, “T”, “O”, and “H” configurations | Adaptive Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) control |

| Riviere et al. (2018) [30] | 2 servo motors; in-plane morphing; weighs 400 g and adjusts from 268 mm unfolded to 128 mm folded wingspan | Reduces wingspan by 48% to navigate through constrained spaces | Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller |

| Wang et al. (2024) [24] | 1 linear actuator; frame-arm length in-plane morphing; weighs 1250 g and adjusts from 410 mm maximum to 310 mm minimum size | Arm length decreases by 24.4%, enabling adaptation to dynamic environments during flight | PID controller |

| Xu et al. (2024) [26] | 1 servo motor; frame-arm length in-plane morphing; weighs 1250 g and adjusts frame size from 48.16 cm extended to 38.62 cm folded | Closed-loop multilink structure with talon links mimicking eagle claw morphology for grasping tasks | Cascade adaptive sliding mode control with admittance filter |

| Singh et al. (2022) [37] | 8 servo motors; tilting rotor, out-of-plane morphing; weighs 2.012 kg with arm lengths of 235 mm | Hyperdynamic QuadPlus platform with 12 degrees of freedom (DoF), enabling attitude control independent of position | Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) |

| Hu et al. (2021) [32] | 4 servo motors; frame-arm angle in-plane morphing; weighs approximately 1.2 kg with compact adjustable arms | Morphing quadrotor with rotatable arms capable of overlapping to minimize width for passing through narrow gaps | Reinforcement learning (RL) with an extended-state approach |

| Sharma et al. (2024) [42] | Linear servo; function extension; weighs 159 g (excluding the balloon) and uses 60 cm and 90 cm diameter balloons | Hybrid blimp-drone platform with integrated failure detection and recovery mechanisms for balloon system | Multi-sensor fusion with PID control |

| Wu et al. (2023) [25] | 1 servo motor with slider; frame-arm length in-plane morphing; weighs approximately 1 kg and spans 41.4 cm × 41.4 cm extended, reducing to 28.4 cm × 28.4 cm retracted | Single servo motor reduces vehicle size by 31.4% during flight | Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) strategy |

| Ruiz et al. (2022) [49] | 4 servo motors; out-of-plane morphing; weighs approximately 1.8 kg with adjustable arms for dynamic configuration | Quasi-static arm deformations modeled and feedback into the autopilot system | PID controller |

| Haluska et al. (2022) [44] | Soft Pneumatic Actuators (SPA); bending frame-arm in-plane morphing; weighs 1 kg and measures 490 mm × 490 mm × 130 mm | Soft pneumatic actuated morphing enabling transitions between “X” and “H” configurations | PID controller |

| Kamel et al. (2018) [83] | 6 servo motors; tilting rotor, out-of-plane morphing; weighs 3.2 kg and utilizes tiltable rotors | Hexacopter with tiltable rotors allowing decoupling of position and orientation control | Nonlinear Model Predictive Attitude Control |

| Desbiez et al. (2017) [29] | 1 servo motor; frame-arm angle in-plane morphing; weighs 380 g with an adjustable arm span of 21 cm per arm | X-Morf robot dynamically adjusts arm angles by up to 28.5% during flight, improving stability and attitude tracking | Model Reference Adaptive Control (MRAC) |

| Kumar et al. (2020) [51] | 2 servo motors with belt; frame-arm length in-plane morphing; weighs 1.56 kg with a nominal arm length of 0.25 m | Considers dynamic shifts in center of gravity (CoG) affecting moment of inertia (MoI) | PID controller |

References

- Floreano, D.; Wood, R.J. Science, technology and the future of small autonomous drones. Nature 2015, 521, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Yuan, G.; Song, L.; Zhang, H. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Landslide Investigation and Monitoring: A Review. Drones 2024, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, T.; Schmid, K.; Lutz, P.; Domel, A.; Kassecker, M.; Mair, E.; Grixa, I.L.; Ruess, F.; Suppa, M.; Burschka, D. Toward a fully autonomous UAV: Research platform for indoor and outdoor urban search and rescue. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nex, F.; Remondino, F. UAV for 3D mapping applications: A review. Appl. Geomat. 2014, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.; Moore, J.; Hovet, S.; Box, J.; Perry, J.; Kirsche, K.; Lewis, D.; Tse, Z.T.H. State-of-the-art technologies for UAV inspections. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2018, 12, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klavins, E.; Zagursky, V. Unmanned aerial vehicle movement trajectory detection in open environment. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 104, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmerico, J.; Mintchev, S.; Giusti, A.; Gromov, B.; Melo, K.; Horvat, T.; Cadena, C.; Hutter, M.; Ijspeert, A.; Floreano, D.; et al. The current state and future outlook of rescue robotics. J. Field Robot. 2019, 36, 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvagni, M.; Tonoli, A.; Zenerino, E.; Chiaberge, M. Multipurpose UAV for search and rescue operations in mountain avalanche events. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycuick, C.J. The flight of birds and other animals. Aerospace 2015, 2, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.; Sanders, B.; Weisshaar, T. Evaluating the impact of morphing technologies on aircraft performance. In Proceedings of the 43rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 22–25 April 2002; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2002; p. 1631. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; He, G. Engineering perspective on bird flight: Scaling, geometry, kinematics and aerodynamics. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2023, 142, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaj, R.M.; Parancheerivilakkathil, M.S.; Amoozgar, M.; Friswell, M.I.; Cantwell, W.J. Recent developments in the aeroelasticity of morphing aircraft. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2021, 120, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarino, S.; Bilgen, O.; Ajaj, R.M.; Friswell, M.I.; Inman, D.J. A Review of Morphing Aircraft. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2011, 22, 823–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, D.; Kleber, K.; Mintchev, S.; Floreano, D.; Scaramuzza, D. The Foldable Drone: A Morphing Quadrotor That Can Squeeze and Fly. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, I. Review of state of art of smart structures and integrated systems. AIAA J. 2002, 40, 2145–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.A. Dynamics and Control of a Quadrotor with Active Geometric Morphing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, K.; Zhang, W. Towards reconfigurable and flexible multirotors: A literature survey and discussion on potential challenges. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 2021, 5, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, R.; Goerres, J.; Aarts, R.; Engelen, J.B.; Stramigioli, S. Fully actuated multirotor UAVs: A literature review. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2020, 27, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Xia, R.; Jin, X.; Tang, Y. Motion planning and control of a morphing quadrotor in restricted scenarios. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 5759–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lee, H.; Jeong, M.; Myung, H. A Morphing Quadrotor that Can Optimize Morphology for Transportation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DJI. DJI Inspire 3. Available online: https://www.dji.com/inspire-3 (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Zhao, N.; Luo, Y.; Deng, H.; Shen, Y. The Deformable Quad-Rotor: Design, Kinematics and Dynamics Characterization, and Flight Performance Validation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N.; Yang, W.; Peng, C.; Wang, G.; Shen, Y. Comparative Validation Study on Bioinspired Morphology-Adaptation Flight Performance of a Morphing Quad-Rotor. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 5145–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, K. A Novel Morphing Quadrotor UAV with Sarrus-Linkage-Based Reconfigurable Frame. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Reconfigurable Mechanisms and Robots (ReMAR), Chicago, IL, USA, 24–27 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Xu, C. Ring-Rotor: A Novel Retractable Ring-Shaped Quadrotor with Aerial Grasping and Transportation Capability. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2126–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; De, Q.; Yu, D.; Hu, A.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H. Biomimetic Morphing Quadrotor Inspired by Eagle Claw for Dynamic Grasping. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 2513–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornatowski, P.M.; Feroskhan, M.; Stewart, W.J.; Floreano, D. A Morphing Cargo Drone for Safe Flight in Proximity of Humans. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 4233–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, A.; Aucone, E.; Mintchev, S. Crash 2 Squash: An Autonomous Drone for the Traversal of Narrow Passageways. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2200113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbiez, A.; Expert, F.; Boyron, M.; Diperi, J.; Viollet, S.; Ruffier, F. X-Morf: A crash-separable quadrotor that morfs its X-geometry in flight. In Proceedings of the 2017 Workshop on Research, Education and Development of Unmanned Aerial Systems (RED-UAS), Linkoping, Sweden, 3–5 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviere, V.; Manecy, A.; Viollet, S. Agile Robotic Fliers: A Morphing-Based Approach. Soft Robot. 2018, 5, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avant, T.; Lee, U.; Katona, B.; Morgansen, K. Dynamics, Hover Configurations, and Rotor Failure Restabilization of a Morphing Quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual American Control Conference (ACC), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 27–29 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 4855–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Pei, Z.; Shi, J.; Tang, Z. Design, Modeling and Control of a Novel Morphing Quadrotor. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 8013–8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrouaoui, S.; Bouzid, Y.; Guiatni, M.; Dib, I.; Moudjari, N. Design and Modeling of Unconventional Quadrotors. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), Saint-Raphael, France, 16–19 June 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryll, M.; Bulthoff, H.H.; Giordano, P.R. A Novel Overactuated Quadrotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: Modeling, Control, and Experimental Validation. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2015, 23, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, S.; Mehrez, O.; Kabeel, A. A novel modification for a quadrotor design. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Arlington, VA, USA, 7–10 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 702–710. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, P.; Tan, X.; Kocer, B.B.; Yang, E.; Kovac, M. TiltDrone: A fully-actuated tilting quadrotor platform. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 6845–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Mehndiratta, M.; Feroskhan, M. QuadPlus: Design, Modeling, and Receding-Horizon-Based Control of a Hyperdynamic Quadrotor. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 1766–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odelga, M.; Stegagno, P.; Bulthoff, H.H. A fully actuated quadrotor UAV with a propeller tilting mechanism: Modeling and control. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, AIM 2016, Banff, AB, Canada, 12–15 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ryll, M.; Bicego, D.; Franchi, A. Modeling and control of FAST-Hex: A fully-actuated by synchronized-tilting hexarotor. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 9–14 October 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1689–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Kawasaki, K.; Chen, X.; Noda, S.; Okada, K.; Inaba, M. Whole-body aerial manipulation by transformable multirotor with two-dimensional multilinks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 5175–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Anzai, T.; Shi, F.; Chen, X.; Okada, K.; Inaba, M. Design, Modeling, and Control of an Aerial Robot DRAGON: A Dual-Rotor-Embedded Multilink Robot with the Ability of Multi-Degree-of-Freedom Aerial Transformation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Verhoeff, M.; Joosen, F.; Prasad, R.V.; Hamaza, S. A Morphing Quadrotor-Blimp with Balloon Failure Resilience for Mobile Ecological Sensing. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 6408–6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Xiao, F.; Nguyen, P.H.; Farinha, A.; Kovac, M. Metamorphic aerial robot capable of mid-air shape morphing for rapid perching. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haluska, J.; Vastanalv, J.; Papadimitriou, A.; Nikolakopoulos, G. Soft pneumatic actuated morphing quadrotor: Design and development. In Proceedings of the 2022 30th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), Athens, Greece, 28 June–1 July 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Chirarattananon, P. SplitFlyer Air: A Modular Quadcopter That Disassembles Into Two Bicopters Mid-Air. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 4729–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, K.; Mishra, S.; Sorkhabadi, S.M.R.; Zhang, W. Design and Control of SQUEEZE: A Spring-augmented QUadrotor for intEractions with the Environment to squeeZE-and-fly. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucki, N.; Mueller, M.W. Design and Control of a Passively Morphing Quadcopter. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fabris, A.; Kirchgeorg, S.; Mintchev, S. A soft drone with multi-modal mobility for the exploration of confined spaces. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), New York, NY, USA, 25–27 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, F.; Arrue, B.C.; Ollero, A. SOPHIE: Soft and Flexible Aerial Vehicle for Physical Interaction with the Environment. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 11086–11093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintchev, S.; Daler, L.; L’Eplattenier, G.; Saint-Raymond, L.; Floreano, D. Foldable and self-deployable pocket sized quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Deshpande, A.M.; Wells, J.Z.; Kumar, M. Flight Control of Sliding Arm Quadcopter with Dynamic Structural Parameters. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1358–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintchev, S.; de Rivaz, S.; Floreano, D. Insect-Inspired Mechanical Resilience for Multicopters. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrouaoui, S.H.; Guiatni, M.; Bouzid, Y.; Dib, I.; Moudjari, N. Dynamic Modeling of a Transformable Quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 1–4 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1714–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresk, E.; Nikolakopoulos, G. Full quaternion based attitude control for a quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2013 European Control Conference (ECC), Zurich, Switzerland, 17–19 July 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 3864–3869. [Google Scholar]

- Bouabdallah, S.; Noth, A.; Siegwart, R. PID vs LQ control techniques applied to an indoor micro quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37566), Sendal, Japan, 28 September–2 October 2004; Volume 3, pp. 2451–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Sanchez, I.; Moreno-Valenzuela, J. PID control of quadrotor UAVs: A survey. Annu. Rev. Control 2023, 56, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dydek, Z.T.; Annaswamy, A.M.; Lavretsky, E. Adaptive control of quadrotor UAVs: A design trade study with flight evaluations. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2012, 21, 1400–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Modeling and adaptive control of a quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, Chengdu, China, 5–8 August 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 383–390. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.; Liu, P.; El Saddik, A. Nonlinear adaptive control for quadrotor flying vehicle. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 78, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.; Mung, N.X.; Thanh, H.L.N.N.; Huynh, T.T.; Lam, N.T.; Hong, S.K. Adaptive sliding mode control for attitude and altitude system of a quadcopter UAV via neural network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 40076–40085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmi, H.; Afshinfar, S. Neural network-based adaptive sliding mode control design for position and attitude control of a quadrotor UAV. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, D.W.; Hwang, I. Linear matrix inequality-based nonlinear adaptive robust control of quadrotor. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2016, 39, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, S.; Gupta, D.; Das, L. PID & LQR control for a quadrotor: Modeling and simulation. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Delhi, India, 24–27 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 796–802. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, G.; Virdi, J.; Chowdhary, G. Asynchronous deep model reference adaptive control. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning, PMLR, London, UK, 8–11 November 2021; pp. 984–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.B.; Marshall, J.A.; L’Afflitto, A. Constrained robust model reference adaptive control of a tilt-rotor quadcopter pulling an unmodeled cart. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2020, 57, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, K.; Zhang, W. Adaptive Attitude Control for Foldable Quadrotors. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2023, 7, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Yuan, B.; Zhao, X.; Ding, Z.; Chen, S. Adaptive robust constraint-following control for morphing quadrotor UAV with uncertainty: A segmented modeling approach. J. Frankl. Inst. 2024, 361, 106678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Cha, D. Unmanned aerial vehicles using machine learning for autonomous flight; state-of-the-art. Adv. Robot. 2019, 33, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wu, H.N.; Wang, J.W. cc-DRL: A Convex Combined Deep Reinforcement Learning Flight Control Design for a Morphing Quadrotor. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.13054. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, L.; Han, L.; Zhou, B.; Shen, S.; Gao, F. Survey of UAV motion planning. IET Cyber-Syst. Robot. 2020, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sárosi, J.; Biro, I.; Nemeth, J.; Cveticanin, L. Dynamic modeling of a pneumatic muscle actuator with two-direction motion. Mech. Mach. Theory 2015, 85, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Nagar, H.; Singh, I.; Sehgal, S. Smart materials types, properties and applications: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 28, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Pei, X.; Wang, T.; Hou, T.; Yang, X. Bioinspiration review of Aquatic Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (AquaUAV). Biomim. Intell. Robot. 2024, 4, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Asignacion, A.; Nakata, T.; Suzuki, S.; Liu, H. Review of biomimetic approaches for drones. Drones 2022, 6, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, M.; Skelton, R.E. Markov data-based reference tracking control to tensegrity morphing airfoils. Eng. Struct. 2023, 291, 116430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Skelton, R.E. Design and control of tensegrity morphing airfoils. Mech. Res. Commun. 2020, 103, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shen, Y.; Skelton, R.E. Model-Based and Markov Data-Based Linearized Tensegrity Dynamics and Analysis of Morphing Airfoils. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2024 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–12 January 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, A.T.; Koubaa, A.; Ali Mohamed, N.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Ibrahim, Z.F.; Kazim, M.; Ammar, A.; Benjdira, B.; Khamis, A.M.; Hameed, I.A.; et al. Drone deep reinforcement learning: A review. Electronics 2021, 10, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMahamid, F.; Grolinger, K. Autonomous unmanned aerial vehicle navigation using reinforcement learning: A systematic review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Song, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Q. A review of small UAV navigation system based on multi-source sensor fusion. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 18926–18948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, M.H.; Abdullah, S.S.; Aras, M.S.M.; Bahar, M.B. Sensor fusion technology for unmanned autonomous vehicles (UAV): A review of methods and applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 9th International Conference on Underwater System Technology: Theory and Applications (USYS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 5–6 December 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.; Molina, J.M.; Trincado, J. Real evaluation for designing sensor fusion in UAV platforms. Inf. Fusion 2020, 63, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.; Verling, S.; Elkhatib, O.; Sprecher, C.; Wulkop, P.; Taylor, Z.; Siegwart, R.; Gilitschenski, I. The Voliro Omniorientational Hexacopter: An Agile and Maneuverable Tiltable-Rotor Aerial Vehicle. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2018, 25, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xing, S.; Zhang, X.; Tian, J.; Xie, C.; Chen, Z.; Sun, J. Morphing Quadrotors: Enhancing Versatility and Adaptability in Drone Applications—A Review. Drones 2024, 8, 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8120762

Xing S, Zhang X, Tian J, Xie C, Chen Z, Sun J. Morphing Quadrotors: Enhancing Versatility and Adaptability in Drone Applications—A Review. Drones. 2024; 8(12):762. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8120762

Chicago/Turabian StyleXing, Siyuan, Xuhui Zhang, Jiandong Tian, Chunlei Xie, Zhihong Chen, and Jianwei Sun. 2024. "Morphing Quadrotors: Enhancing Versatility and Adaptability in Drone Applications—A Review" Drones 8, no. 12: 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8120762

APA StyleXing, S., Zhang, X., Tian, J., Xie, C., Chen, Z., & Sun, J. (2024). Morphing Quadrotors: Enhancing Versatility and Adaptability in Drone Applications—A Review. Drones, 8(12), 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8120762