Abstract

Objectives: Perioperative blood transfusion (PBT) has been associated with worse survival after radical cystectomy (RC) in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Here, we evaluated the association between PBT and survival after RC that was preceded by neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). Methods: A retrospective analysis was performed on 949 patients with cT2-4aN0M0 bladder cancer who received NAC prior to RC between 2000 and 2013 at 19 centers. Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival (OS) were made. Presumed risk factors for OS were analyzed using Cox regression analysis. PBT was defined by the administration of any packed red blood cells during surgery or during the post-operative hospital stay. Results: A transfusion was given to 608 patients (64%). Transfused patients were more likely to have adverse clinical and pathologic parameters, including clinical stage and performance status. Transfused patients had worse OS (p = 0.01). On multivariable Cox regression, PBT was found to be independently associated with worse OS (HR 1.53 (95% CI 1.13–2.08), p = 0.007). Conclusions: PBT is common after NAC and RC, which may be linked, in part, to the anemia induced by NAC. PBT was associated with several adverse risk factors that correlate with poor outcomes after NAC and RC, and it was an independent predictor of adverse OS on multivariable analysis. Further study should determine if measures to avoid blood loss can reduce the need for PBT and thereby improve patient outcomes.

1. Introduction

Radical cystectomy (RC) is the standard of care for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) who are surgical candidates [1]. Although there are high rates of morbidity and mortality associated with radical cystectomy, perioperative patient optimization, including management of pre-operative anemia and judicious use of blood products during and after surgery, are important considerations to improve patient outcomes [2].

The risks associated with perioperative blood transfusions (PBT) are well known and have been described for patients with a variety of malignancies, including biliary, liver, and colon cancers [3,4,5]. These risks include increased cancer recurrence and mortality [6]. There are fewer studies investigating the risk of PBT, specifically in bladder cancer. Of the studies conducted, PBT has been associated with poor outcomes and increased mortality in patients undergoing RC for MIBC [6,7]. However, no large-scale studies have investigated the impact of PBT in patients undergoing RC after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC).

NAC increases 5-year survival by approximately 5–8% when compared to RC alone and, thus, represents the standard of care for cisplatin-eligible patients with MIBC [8]. However, NAC often results in anemia before patients undergo surgery [9] and, thus, may increase the need for PBT. Roughly 60% of patients undergoing RC without NAC receive PBT [6]. It is possible that this number is greater after NAC due to the resulting anemia, but the impact on patient survival in this context is unknown. The objective of this study was to investigate the association of PBT with survival in patients undergoing RC after NAC for MIBC. We hypothesized that we would identify a similar association in the absence of NAC.

2. Materials and Methods

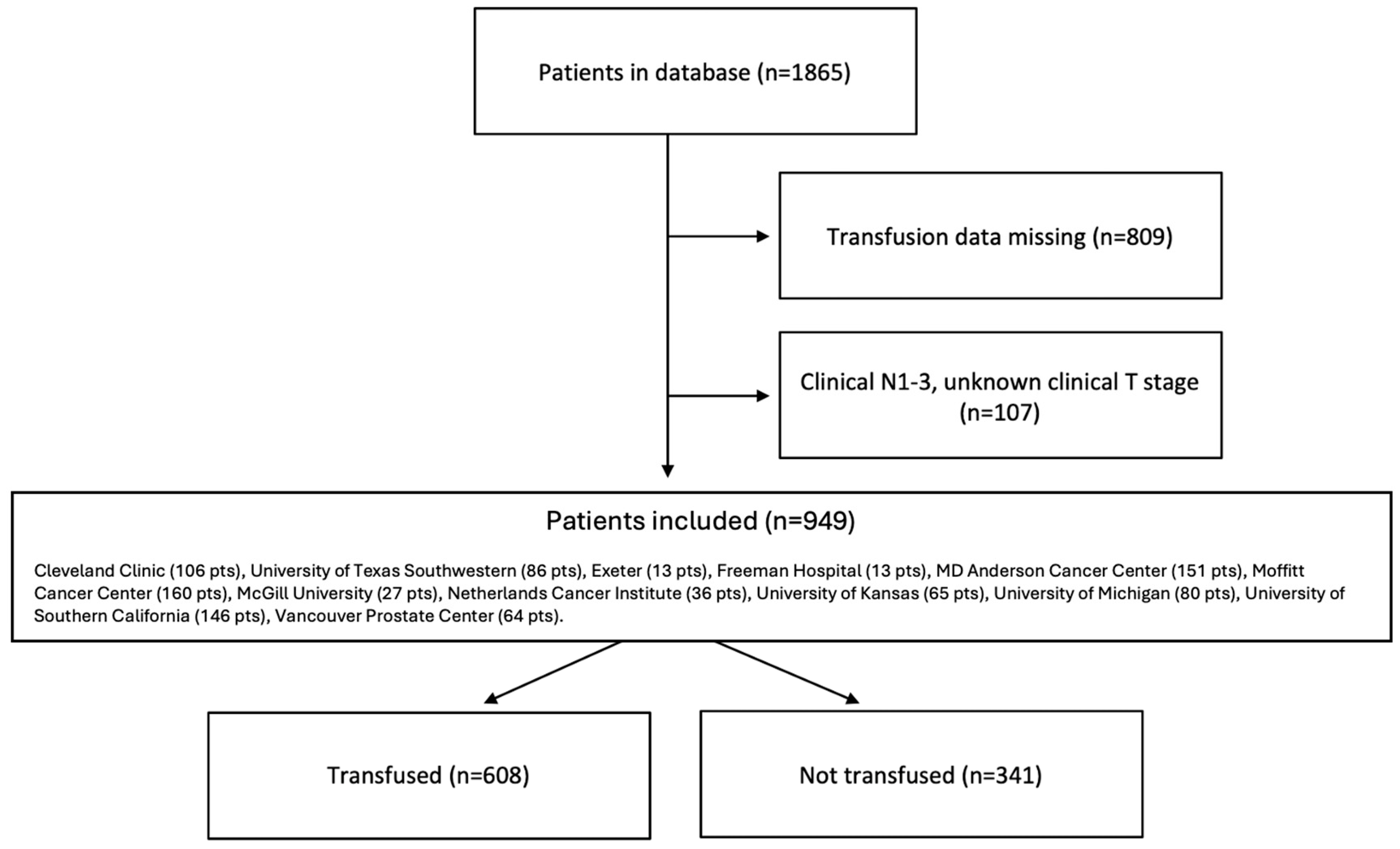

Data from medical records of 1865 patients who underwent radical cystectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy between 2000 and 2013 were retrospectively collected from 19 centers across Europe and North America [10]. Data were collected under the approval of each institution’s clinical research ethics board. Data were then de-identified and shared based on data transfer agreements between the institutions.

Only patients with cT2-4aN0M0 bladder cancer for whom blood transfusion data were available were included in this analysis. PBT was defined as any administration of packed red blood cells during or after surgery until discharge from the hospital. Patients were then classified accordingly as “transfused” or “not transfused”.

Statistical Analysis

Demographics (age, sex, race, BMI), pre-operative clinicopathologic characteristics (smoking history, transfusion status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), clinical T-stage, hemoglobin, platelet count), treatment, and pathologic parameters (NAC regime, number of NAC cycles, pathologic T and N stages, and response to NAC) were found for both patients who were and were not transfused. All variables were summarized in descriptive statistics, including mean and/or standard deviation.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) between the transfused and non-transfused groups. Differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank method. A multivariable analysis was conducted using a Cox regression, including the following variables: age; sex; clinical T-stage; pre-cystectomy hemoglobin; number of NAC cycles; and NAC regimen. An additional multivariable analysis was conducted with transfusion as a continuous variable. Variables used in the multivariable analysis were based on those chosen by other similar studies, including those conducted by Morgan et al., 2013 [7], and included age, sex, smoking history, clinical T-stage, pre-cystectomy hemoglobin, and transfusion status. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS-v.25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

A total of 949 patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). All patients were from high-volume surgical centers, including Cleveland Clinic (107 pts), University of Texas Southwestern (86 pts), Exeter (13 pts), Freeman Hospital (13 pts), MD Anderson Cancer Center (151 pts), Moffitt Cancer Center (160 pts), McGill University (27 pts), Netherlands Cancer Institute (36 pts), University of Kansas (65 pts), University of Michigan (80 pts), University of Southern California (146 pts), and Vancouver Prostate Center (64 pts). Six hundred and eight patients (64.1%) received PBT and formed the “transfused group”, while 341 (35.9%) were in the “not transfused” group. The median number of units of blood transfused in those who received PBT was 3.0 (IQR 2.0–4.0).

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram.

Clinicopathologic demographics for the two groups can be found in Table 1 as well as clinicopathologic demographics for the entire population (all patients included in the original data set) in Table 2. The mean age in the transfused group was greater (67.0 ± 23.1 years) than in the not transfused group (62.8 ± 9.3 years). Clinical T3-4 disease was present in 46.9% of transfused patients but only 39.3% of those not transfused. A higher proportion of those in the transfused group were female (26.9% vs. 15.5%), and a lower proportion had an ECOG performance status of 0 (40.7% vs. 49.3%). Paradoxically, the pre-operative hemoglobin was lower in the group that was not transfused.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of multicenter patient cohort included in study.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of multicenter patient cohort present in database before inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied.

Treatment variables and pathologic outcomes are summarized in Table 3. There were significant differences between the groups in terms of NAC regimen, number of NAC cycles, pathologic T-stage, and response to NAC. Just over half of the patients (50.6%) in our study received gemcitabine-cisplatin chemotherapy. Transfused patients were more likely to have received MVAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, adriamycin, and cisplatin) and were more likely to have received four or more cycles of NAC. Transfused patients had higher pathologic T-stage (44.6% vs. 33.8% with ypT3-T4). Furthermore, residual muscle-invasive disease was found in 63.9% of transfused patients, compared to only 53.4% of those not transfused. There was no difference between groups in terms of pathologic N-stage.

Table 3.

Treatment and pathologic characteristics of multicenter patient cohort undergoing open radical cystectomy.

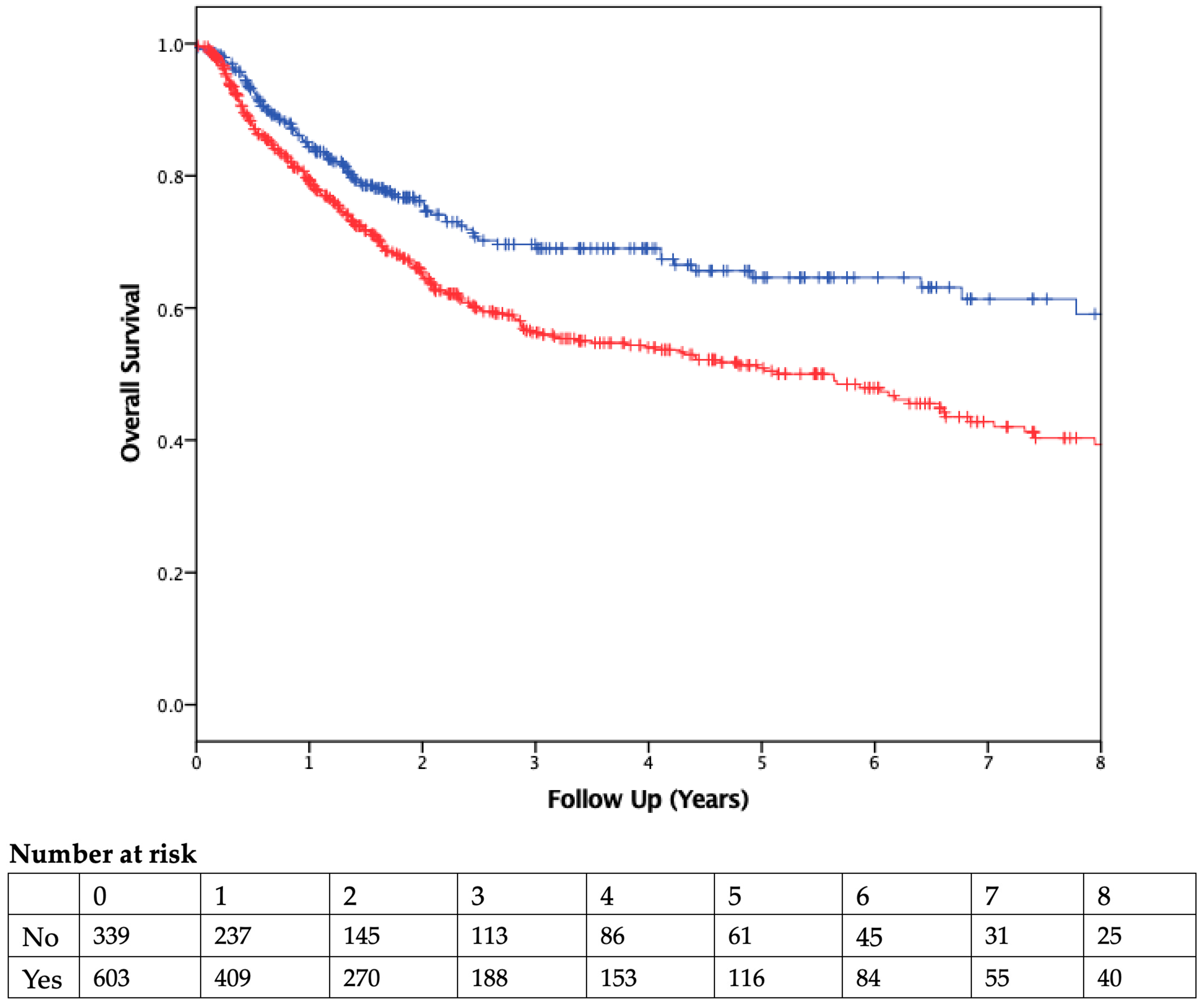

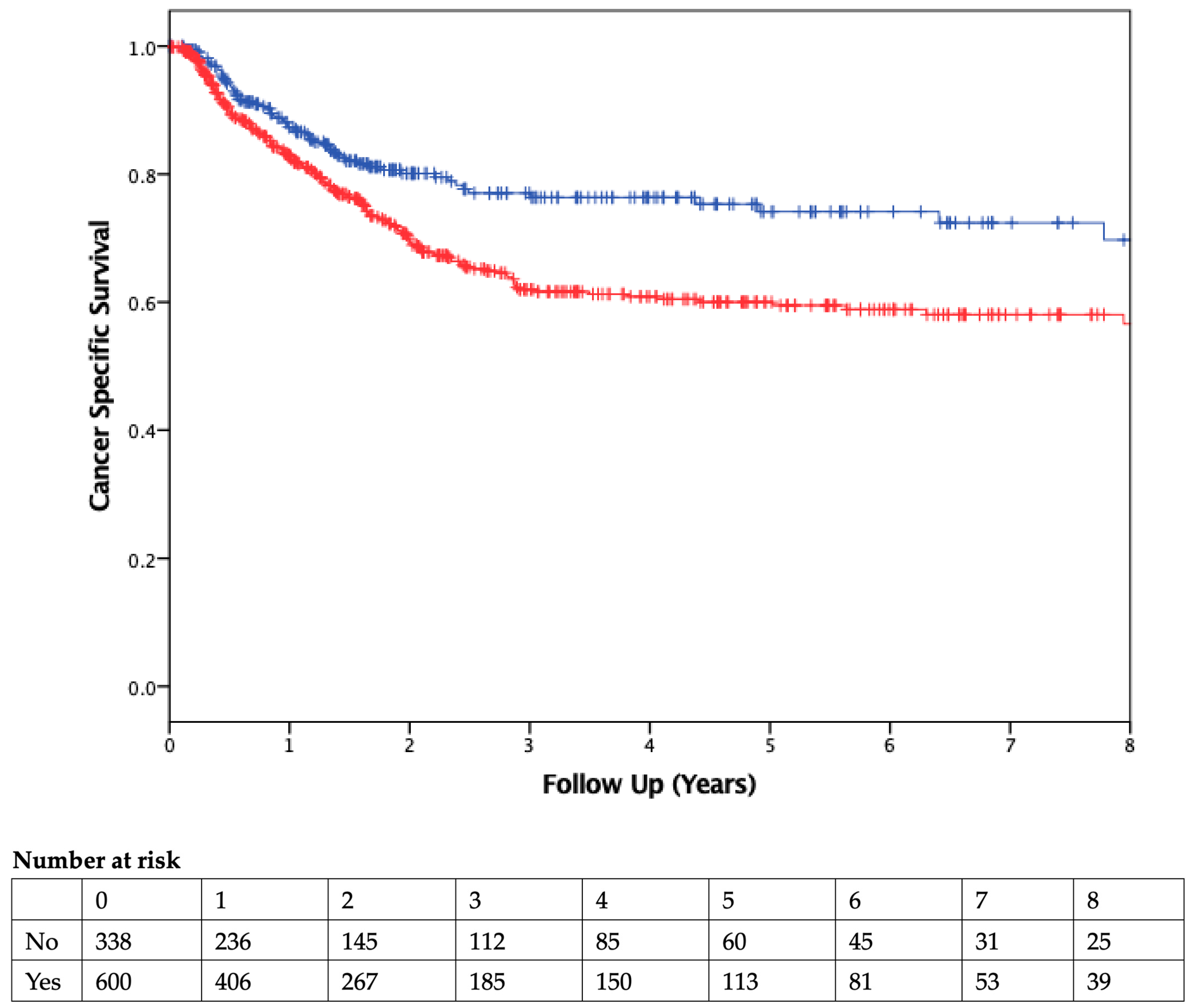

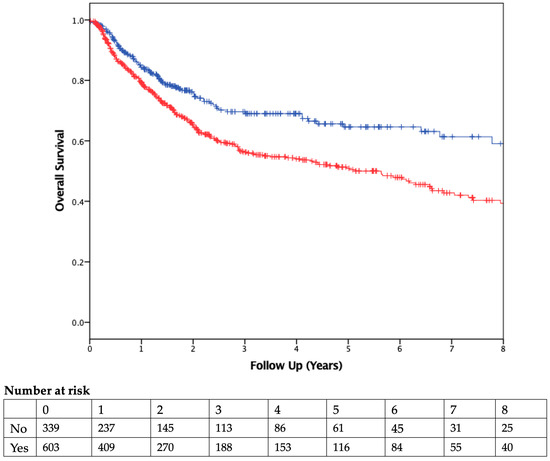

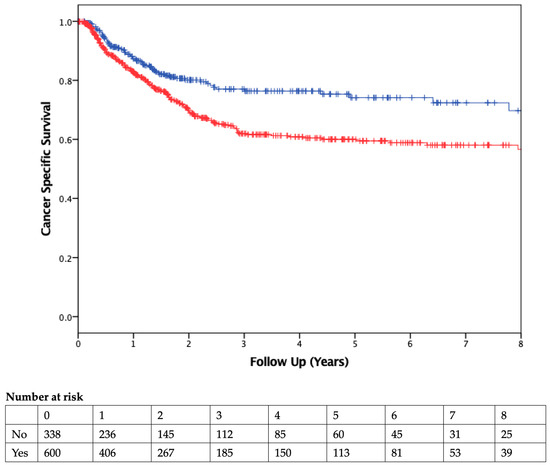

The median duration of follow-up was 2.51 years. Patients who received PBT had worse OS than those who were not transfused (Figure 2). On Cox regression multivariable analysis (Table 4), transfusion was independently associated with worse OS as a dichotomous variable (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.3–2.1; p = 0.007) and as a continuous variable (HR 1.09, 95% CI 1.05–1.13, p < 0.001; Table 5). CSS was also found to be significantly different between the two groups, with transfused patients having worse CSS (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Overall Survival. Kaplan–Meier curve comparing overall survival of patients who did (red) or did not (blue) receive a blood transfusion. Vertical ticks represent censored patients, while numbers below the x-axis represent the number of patients at risk in each group in 1-year intervals (p = 0.001, using the log-rank method).

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis (Cox regression) for predictors of overall survival.

Table 5.

Multivariable analysis (Cox regression) for predictors of overall survival, with blood transfusion as a continuous variable.

Figure 3.

Cancer-Specific Survival. Kaplan–Meier curve comparing cancer-specific survival of patients who did (red) or did not (blue) receive a blood transfusion. Vertical ticks represent censored patients, while numbers below the x-axis represent the number of patients at risk in each group in 1-year intervals (p < 0.01, using the log-rank method).

PBT was required intra-operatively in 569 (53.1%) patients and post-operatively in 350 patients (32.6%). Both were found to have a significant association with worse OS (Table 6). Of 350 patients who received post-op PBT, 243 (69%) also received an intra-operative PBT. In a subgroup analysis that excluded patients who received intra-op PBT, post-op PBT was not significantly associated with OS (p = 0.77, 252 patients) (Table 7).

Table 6.

Multivariable analysis (Cox regression) for predictors of overall survival, with transfusion (PBT) as a continuous variable separated into intra-operative and post-operative blood transfusions.

Table 7.

Multivariable analysis (Cox regression) for predictors of overall survival, with transfusion (PBT) as a continuous variable and excluding patients who received intra-operative blood transfusion (p = 0.77, 252 patients).

4. Discussion

Although a number of studies have addressed the relationship between PBT and outcome after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer [6,7,11,12,13], this is, to our knowledge, the first large-scale retrospective study investigating this relationship in patients receiving NAC prior to RC. We found that PBT was an independent risk factor for worse OS. Since PBT was also associated with worse CSS, our results suggest that PBT has a negative effect on cancer control. Our findings were consistent with the numerous publications on RC without NAC. We further found a dose response between the number of units transfused and OS. For every additional unit of blood transfused, the likelihood of survival decreased by 8.9%. This is consistent with what has already been published in the literature. For example, Linder et al. [6] found a dose response between the number of units of blood transfused and all-cause mortality for patients undergoing radical cystectomy.

The negative impact of PBT is thought to be due to its immunosuppressive effect, also known as transfusion-associated immunomodulation (TRIM), although the exact mechanism by which PBT leads to cancer recurrence is not well understood [4]. It has been speculated that this effect is due to immune system downregulation via decreased natural killer cell function and helper T-cell ratios, poor antigen presentation, and decreased cell-mediated immunity [14]. Interestingly, several recent studies have found that the timing of PBT was critical, with intra-operative PBT having a negative effect on OS and post-operative PBT having no significant effect [15,16]. The authors hypothesized that intraoperative immune perturbation through PBT impacted outcomes more because the immune system was still exposed to tumor antigens at the time of PBT. In our series, PBT impacted OS in both settings.

The specific question in this study was whether the negative association between PBT and survival that has been reported in multiple RC series would also be observed in patients receiving NAC prior to RC. NAC adds one additional element to cause anemia in addition to patient- and disease-related factors that cause pre-operative anemia and intra-operative blood loss during cystectomy. It is expected that the additional anemia caused by NAC will increase the need for PBT [17]. We cannot draw any specific conclusions in this regard since the PBT rate in our series (64%) was similar to that reported in other studies in which patients had not received NAC [6,11]. On the other hand, patients in our series were more likely to receive PBT if they received ≥four cycles of NAC or if they received MVAC, which suggests a role for the chemotherapy itself in driving the anemia that led to PBT. Alternatively, these could be parameters that reflect more advanced cancer, which, in turn, explains the need for PBT. Measures of higher disease burden in the transfused group also included higher clinical and pathologic T stage and a higher rate of residual muscle-invasive disease.

Female patients were more likely to require PBT in our series, which is consistent also with other cystectomy series [7,17]. This likely reflects anatomic differences. Advanced age is also a reproducible risk factor for needing PBT, as shown in our series and other reports [17]. All cases were performed in an open fashion in this series, but an increasing proportion of RC is being performed robotically today. It is established that robotic RC reduces blood loss and the need for PBT compared to open RC [18,19]. The question must, therefore, be addressed as to whether the associated avoidance of PBT could have a beneficial impact on patient survival and, thus, potentially create a larger push toward completing these cases robotically.

This study is inherently limited by its retrospective nature. Additionally, several patients were excluded from our analysis due to missing variables. Despite attempting to rule out any confounding with our multivariable analysis, it is likely that there are still confounding variables influencing our results. In particular, we have no means to control individual physician and center selection bias in determining the need for PBT, which would likely be governed by different thresholds in different locations. This threshold is often determined at the discretion of anesthesia, related to significant intra-operative blood loss, patient comorbidities, or hemodynamic instability. Unfortunately, our data included neither estimated intra-operative blood loss nor precise transfusion thresholds of each center, and thus, we cannot comment on the predictive value of these variables. We were unable to report recurrence-free survival due to missing data with respect to the date of recurrence. Additionally, we could not control for all cancer-specific factors, including surgical difficulty. Although our analysis identified PBT as independently associated with worse OS, these cancer-specific factors may have been major contributors to both PBT and OS. Finally, the association between PBT and outcome does not necessarily mean that interventions to overcome pre-operative anemia, reduce intraoperative blood loss, and reduce PBT will improve patient outcomes. Beyond the apparent validity of such measures to improve patient care, interventional studies would be needed to demonstrate the causality and ability to utilize these parameters for therapeutic benefit.

Although the multivariable analysis identified PBT as an independent variable associated with OS, not all cancer-related factors can be controlled adequately, and cancer-related difficulty is still likely to be a major contributor to PBT and OS.

5. Conclusions

PBT is associated with several adverse risk factors that correlate with poor outcomes after NAC and RC. Furthermore, we found PBT to be an independent predictor of OS on multivariable analysis, with a dose response suggesting an increase in mortality with an increasing number of units transfused. Comprehensive care pathways to optimize patient management before, during, and after RC already include measures to overcome anemia and reduce PBT. While it is assumed that these measures equate with optimal patient care, it remains to be determined whether such interventions will improve survival outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.B. Data collection and curation: all authors. Formal analysis, T.L., A.J.B. and P.C.B. Writing—original draft preparation, T.L., A.J.B. and P.C.B.; writing—review and editing, all authors. Supervision: J.L.W., A.C.T., T.M.M., J.M.H., M.S.C., N.-E.J., C.P.N.D., J.S.M. (Jeffrey S. Montgomery), E.Y.Y., A.J.S., J.B.S., S.D., P.E.S., L.S.M., B.W.G.v.R., P.G., W.K., M.A.D., S.S.S., J.S.M. (Jonathan S. McGrath), S.F.S., T.J.B., S.A.N., D.A.B., Y.L. and P.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of each institution.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Peter C. Black.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aminoltejari, K.; Black, P.C. Radical cystectomy: A review of techniques, developments and controversies. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 9, 3073–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leow, J.J.; Bedke, J.; Chamie, K.; Collins, J.W.; Daneshmand, S.; Grivas, P.; Heidenreich, A.; Messing, E.M.; Royce, T.J.; Sankin, A.I.; et al. SIU–ICUD consultation on bladder cancer: Treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. World J. Urol. 2019, 37, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Aguiar, A.G.; Ethun, C.G.; Pawlik, T.M.; Tran, T.; Poultsides, G.A.; Isom, C.A.; Idrees, K.; Krasnick, B.A.; Fields, R.C.; Salem, A.; et al. Association of perioperative transfusion with recurrence and survival after resection of distal cholangiocarcinoma: A 10-institution study from the US extrahepatic biliary malignancy consortium. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 1814–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cata, J.P.; Wang, H.; Gottumukkala, V.; Reuben, J.; Sessler, D.I. Inflammatory response, immunosuppression, and cancer recurrence after perioperative blood transfusions. Br. J. Anaesth. BJA 2013, 110, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, S.; Baker, L.K.; Martel, G.; Shorr, R.; Pawlik, T.M.; Tinmouth, A.; McIsaac, D.I.; Hébert, P.C.; Karanicolas, P.J.; McIntyre, L.; et al. The impact of perioperative red blood cell transfusions in patients undergoing liver resection: A systematic review. HPB 2017, 19, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder, B.J.; Frank, I.; Cheville, J.C.; Tollefson, M.K.; Thompson, R.H.; Tarrell, R.F.; Thapa, P.; Boorjian, S.A. The impact of perioperative blood transfusion on cancer recurrence and survival following radical cystectomy. Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, T.M.; Barocas, D.A.; Chang, S.S.; Phillips, S.E.; Salem, S.; Clark, P.E.; Penson, D.F.; Smith, J.A.; Cookson, M.S. The relationship between perioperative blood transfusion and overall mortality in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2013, 31, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Advanced Bladder Cancer (ABC) Meta-analysis Collaboration. Adjuvant chemotherapy in invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data Advanced Bladder Cancer (ABC) Meta-analysis Collaboration. Eur. Urol. 2005, 48, 189–199, discussion 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinga, G.; Sherif, A. A retrospective evaluation of preoperative anemia in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive urothelial urinary bladder cancer, with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zargar, H.; Espiritu, P.N.; Fairey, A.S.; Mertens, L.S.; Dinney, C.P.; Mir, M.C.; Krabbe, L.-M.; Cookson, M.S.; Jacobsen, N.-E.; Black, P.C.; et al. Multicenter assessment of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, E.J.; Linder, B.J.; Bauman, T.M.; Bauer, R.M.; Thompson, R.H.; Thapa, P.; Devon, O.N.; Tarrell, R.F.; Frank, I.; Jarrard, D.F.; et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and radical cystectomy: Does timing of transfusion affect bladder cancer mortality? Eur. Urol. 2014, 66, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas, J.; Gregorio, S.; Ledo, J.; Gómez, Á.; Sebastián, J.; de la Peña Barthel, J. The role of perioperative blood transfusion on postoperative outcomes and overall survival in patients after laparoscopic radical cystectomy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2016, 12, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchner, A.; Grimm, T.; Schneevoigt, B.-S.; Wittmann, G.; Kretschmer, A.; Jokisch, F.; Grabbert, M.; Apfelbeck, M.; Schulz, G.; Gratzke, C.; et al. Dramatic impact of blood transfusion on cancer-specific survival after radical cystectomy irrespective of tumor stage. Scand. J. Urol. 2017, 51, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordin, J.; Heddle, N.; Blajchman, M. Biologic effects of leukocytes present in transfused cellular blood products. Blood 1994, 84, 1703–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantopoulos, L.N.; Sekar, R.R.; Holt, S.K.; Khaki, A.R.; Miller, N.J.; Gadzinski, A.; Nyame, Y.A.; Vakar-Lopez, F.; Tretiakova, M.S.; Psutka, S.P.; et al. Patterns and timing of perioperative blood transfusion and association with outcomes after radical cystectomy. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 39, 496.e1–496.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, A.; Frank, I.; Shah, P.H.; Tarrell, R.F.; Baird, B.; Dora, C.; Karnes, R.J.; Thompson, R.H.; Tollefson, M.K.; Boorjian, S.A.; et al. Intraoperative Blood Transfusion Is Associated with Increased Risk of Venous Thromboembolism After Radical Cystectomy. J. Urol. 2023, 209, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, D.; Beilstein, C.M.; Jerney, P.; Furrer, M.A.; Burkhard, F.C.; Löffel, L.M.; Wuethrich, P.Y. Predictors for perioperative blood transfusion in patients undergoing open cystectomy and urinary diversion and development of a nomogram: An observational cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Lin, T.; Fan, X.; Xu, K.; Bi, L.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, M.; Li, J.; Huang, J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies reporting early outcomes after robot-assisted radical cystectomy versus open radical cystectomy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 39, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catto, J.W.F.; Khetrapal, P.; Ambler, G.; iROC Study Team. Effect of Robot-Assisted Radical Cystectomy vs. Open Radical Cystectomy on 90-Day Morbidity and Mortality Among Patients with Bladder Cancer-Reply. JAMA 2022, 328, 1258–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).