Abstract

Introduction and Objectives: In the modern context, where fertility is crucial for couples, male factors contribute 40–50% to subfertility. Testicular cancer survivors facing subfertility due to treatments like orchidectomy and chemotherapy can benefit from sperm banking. However, awareness is lacking, especially in culturally sensitive Asian populations where sex and fertility discussions are taboo. This study aims to assess attitudes and utilization of sperm banking, evaluate its impact on pregnancy outcomes, and identify implementation obstacles. Materials and Methods: A phone interview survey targeted testicular cancer patients treated at Hospital Sultanah Aminah Johor Bahru and Sarawak General Hospital in Malaysia (2019–2023). Of the 102 identified patients, 62 participated. Investigators, using contact details from medical records, conducted interviews with a blend of quantitative and qualitative inquiries. Bivariate analysis identified factors linked to the decision to pursue sperm banking. Results: Out of 62 participants, 58.1% were aware of sperm banking, yet 90.3% chose not to utilize it. Reasons for declining included physician non-offer (41.1%), cost concerns (21.4%), a desire for prompt treatment (16.1%), lack of interest (14.3%), and other factors (7.1%). Among six patients opting for sperm banking, 50% utilized banked sperm, resulting in successful progeny for two-thirds. Notably, one case led to multiple pregnancies. Ethnicity (p = 0.046) and religion (p = 0.026) significantly influenced decisions, with Muslim Malays being the least likely to utilize sperm banking. Conclusion: Sperm banking emerges as a cost-effective strategy for safeguarding fertility in testicular cancer patients. Healthcare providers should proactively offer this option before treatment, ensuring patients are well-informed and addressing concerns to foster informed decisions.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary era, fertility holds paramount importance for the majority of couples. Approximately 15% of couples face challenges in achieving pregnancy within one year and consequently seek medical intervention for infertility. Male factors account for 20% of infertility cases among couples [1]. Some individuals have a history of gonadotoxic chemotherapy, radiation treatment, orchidectomy, or retroperitoneal surgery following their testicular cancer diagnosis. Unfortunately, they may not be aware of the potential negative impact of these treatments on reproductive function [2].

In Malaysia, testicular cancer exhibits a relative rarity, constituting merely 1% of adult neoplasms and 5% of urological tumors. It occupies the 28th position within the spectrum of 32 cancers identified within the nation [3]. Data extracted from the Malaysian National Cancer Registry spanning 2012 to 2016 reveal a tally of 636 recorded cases of testicular cancer during that timeframe [4]. According to the World Health Organization’s Global Cancer Observatory’s statistical records for 2022, Malaysia documented 132 novel instances of testicular cancer, resulting in 20 fatalities. Over a five-year span, a prevalence rate of 0.32 cases per 100,000 individuals emerged, summing up to 504 cases. Consequently, it is imperative to delve into comprehensive studies concerning this patient cohort, elucidating their attitudes and cognizance pertaining to fertility preservation.

Testicular cancer contributes to about 5% of male infertility cases. Patients with testicular tumors prior to orchidectomy often exhibit Leydig cell malfunction and sperm abnormalities [5]. Before treatment, azoospermia is found in 24% of testicular tumor patients, and up to 50% exhibit oligozoospermia (abnormal sperm counts) [5]. Ideally, testicular tumor patients should be informed about fertility preservation options before undergoing treatment. If patients express interest in cryopreservation, they should be offered sperm banking before orchidectomy or concomitant onco-TESE (testicular sperm extraction) during orchidectomy. This approach maximizes the chances of fertilization and mitigates the risk of a non-functioning remaining testicle post-surgery. This should be undertaken prior to chemotherapy or radiation treatment if not arranged before orchidectomy [6,7].

Regrettably, many individuals remain unaware of the potential impact of their treatment on subsequent fertility. This lack of awareness is particularly prevalent in the Asian population, where discussions about intercourse and fertility are often considered taboo. Additionally, it may be related to the inadequacy of sexual education in the Malaysian education system [8].

Malaysia provides free to low-cost public healthcare to its citizens, but the lack of a dedicated fertility preservation referral center has historically limited the use of sperm banking services. Government hospitals, such as Hospital Kuala Lumpur, do not offer sperm banking, and private fertility clinics, mostly in urban areas, primarily serve non-oncological cases. A significant milestone occurred on 26 August 2020, when the Ministry of Health established the first National Referral Oncofertility Centre, the Advanced Reproductive Centre (ARC), at Hospital Canselor Tuanku Muhriz (HCTM). This government-subsidized center aims to be a leading oncofertility referral hub, providing nationwide access to affordable sperm banking and storage. The ARC’s establishment improves access to oncofertility services and supports ongoing research to enhance service quality and meet evolving patient needs [9,10]. Before the ARC at HCTM, individuals with limited income and those in rural areas had few options for sperm banking, often undergoing testicular cancer treatment without this crucial service.

In Malaysia, Islam is the national religion. Johor, in southern West Malaysia, has a population of 3.79 million, with 60.1% Malay, 32.8% Chinese, and 6.0% Indian residents. The Department of Urology at Hospital Sultanah Aminah in Johor Bahru provides public urology services for the state. Sarawak, in East Malaysia, has a population of 2.82 million, primarily local Borneos and Malays (72.1%), with Chinese (22.6%) and Indian (0.2%) minorities [11]. Sarawak General Hospital is the urology referral center for Sarawak. Both Johor and Sarawak face similar challenges with sperm banking. Neither Hospital Sultanah Aminah nor Sarawak General Hospital offers in-house sperm banking services. Patients must travel to HCTM in Kuala Lumpur or use expensive private fertility clinics, which include four in Johor Bahru and three in Kuching. This travel, especially for Kuching patients, adds financial strain and potential treatment delays. The study aims to address the lack of data on sperm banking attitudes among Malaysia’s multiethnic population.

Urologists and fertility specialists will only receive subfertility referrals when the patients are married and decide to start a family. This is often years after gonadotoxic treatment. At this point, damage to spermatogenesis has already taken place. Therefore, early discussions with patients on the availability of fertility preservation are important. They should understand the need to preserve their fertility potential and be counseled on the importance of sperm banking before initiating any form of treatment. Research suggests that individuals diagnosed with cancer grapple with ongoing psychological distress linked to fertility-related issues, spanning from diagnosis to survivorship. This distress is compounded by factors such as unfulfilled desires for children, which contribute to heightened rates of mental health disorders [12]. Consequently, it underscores the importance of providing fertility-related psychological support for survivors of testicular cancer.

Sperm banking emerges as the most economically viable approach for preserving fertility when juxtaposed with the expenses linked to surgical sperm retrieval and assisted reproductive technology (ART). In the absence of insurance coverage for male infertility interventions such as micro TESE, patients commonly shoulder substantial financial burdens. These interventions frequently encompass supplementary costs associated with surgical procedures, anesthesia, and ancillary fees. Consequently, sperm banking stands as the preferred cost-effective alternative [13].

Objectives of the Study

The objectives of this research are to assess the attitudes and utilization of sperm banking and its gestational outcomes (procedure success and the number of gestations). Additionally, the study aims to identify barriers to sperm banking (such as lack of interest, cost concerns, urgency to start therapy, and not being offered by healthcare providers) and to explore the relationship between socio-demographic factors (ethnicity, religion, educational level, income, marital status, age, and number of children) and awareness and utilization of sperm banking.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a phone interview survey including all the testicular cancer patients treated in Hospital Sultanah Aminah Johor Bahru and Sarawak General Hospital from the year 2019 to 2023.

2.2. Data Collection

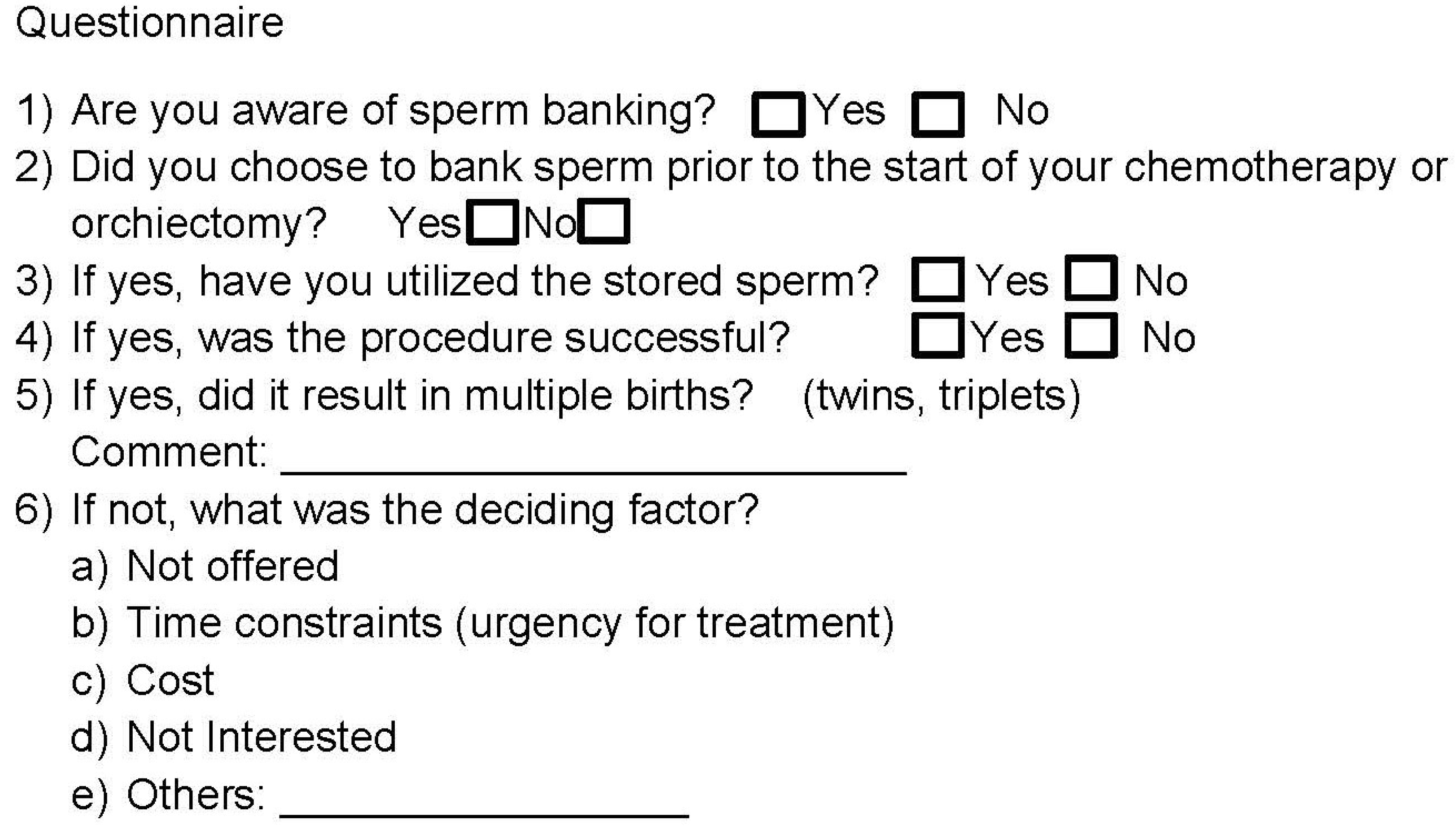

Patients were contacted by the researchers using the phone numbers provided in their medical records. After obtaining informed consent, interviews were conducted to complete a comprehensive study information sheet and a questionnaire. The questionnaire, delineated in Figure 1, was adapted from a prior study conducted by Sonnenburg DW et al. [14]. This questionnaire encompassed a combination of quantitative and qualitative queries, with the latter consisting of open comments elucidating reasons for the absence of sperm banking. These qualitative responses aimed to provide a detailed understanding of the rationale behind patients’ decisions to forego sperm banking. Additionally, the study information sheet included supplementary socio-demographic variables such as age, number of children, ethnicity, religion, educational level, income, and marital status.

Figure 1.

Depicts a phone interview questionnaire adapted from Sonnenburg DW et al.’s [14] previous study. The questionnaire integrates quantitative and qualitative components. The qualitative segment involves open-ended inquiries to elucidate the rationale behind patients opting out of sperm banking, providing a nuanced understanding of their decisions.

2.3. Patient Eligibility Selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- Aged 18 years or older at the time of survey;

- Diagnosis of testicular tumor treated with orchidectomy or chemotherapy;

- Cognitively able to complete a questionnaire to be included in the study.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data were recorded and processed using Microsoft Excel. Subsequently, the data analysis was conducted employing the SPSS version 27 software (IBM SPSS Statistics). Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data and median (Interquartile range) for non-parametric data. The data collected were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. Bivariate analyses were executed, with the level of significance set at 0.05, to examine the relationship between socio-demographic variables and the utilization of sperm banking.

2.5. Privacy and Confidentiality

Participant names were kept in a password-protected database, linked only to study identification numbers. Datasheets used these numbers instead of patient identifiers and were inputted into a password-secured computer. After the study, data were transferred to CDs, stored securely in the investigators’ locked office for a minimum of three years, and then obliterated. Participants could not view individual data but could contact investigators for study findings access.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Data of Study Samples

Of the 102 patients identified from the medical records, 62 patients agreed to take part in the telephone interview. Table 1 illustrates the socio-demographic data of the study samples.

Table 1.

Presents the socio-demographic information of the study participants.

3.2. Sperm Banking Awareness among Testicular Cancer Patients

In the study, 62 patients were included, and among them, 36 patients (58.1%) were aware of sperm banking before undergoing treatment for their testicular cancer. The awareness of sperm banking showed a significant association with their educational background (p < 0.05). Patients with a primary and secondary level of education were less likely to engage in sperm banking compared to those with a diploma and degree (Odds Ratio: 0.1, 95% CI: 0.03–0.33).

3.3. Sperm Banking Utilization and Barriers to Its Use

Of the 62 patients, the majority, 56 patients (90.3%), opted not to avail themselves of sperm banking services. The reasons for declining sperm banking included not being presented with the option by their physician (41.1%), concerns regarding cost (21.4%), a desire to commence treatment promptly (16.1%), a lack of interest (14.3%), and various other factors (7.1%). Among these various factors, open-ended questions revealed that three individuals cited their adherence to Islam, where their religious beliefs prohibited them from sperm banking. Additionally, one patient mentioned having oligozoospermia.

3.4. Examining Gestational Outcomes Following Sperm Banking

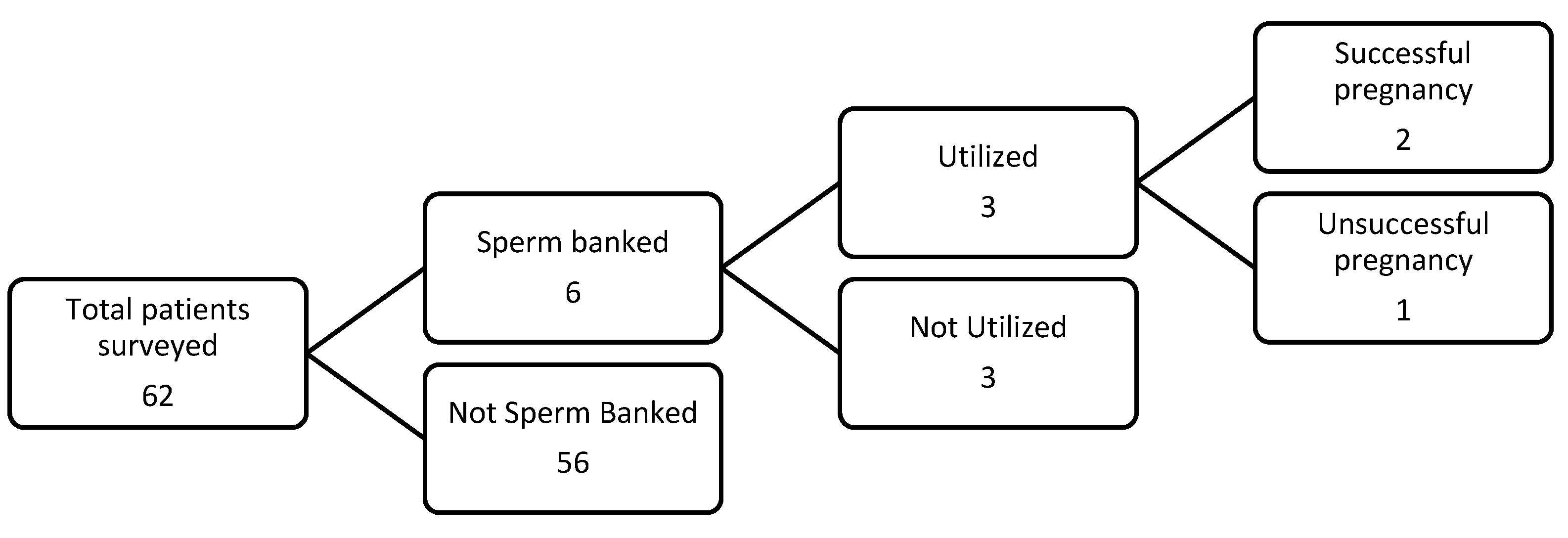

Within a cohort of six patients, constituting 9.7% of the total sample, who opted for sperm banking, an impressive 50% ultimately utilized the stored sperm. Among these patients, two-thirds achieved successful pregnancies, resulting in a commendable 67% success rate. Upon analyzing the sperm of two patients, it was found that both had normal sperm parameters. Interestingly, one of them achieved a singleton pregnancy, while the other achieved a triplet pregnancy. This underscores a favorable outcome in terms of fertility preservation before undergoing gonadotoxic testicular cancer treatment. It emphasizes the effectiveness of sperm banking as a promising option for individuals aiming to preserve their reproductive capabilities. The results are illustrated in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2.

Illustrates the summary of assessing gestational outcomes after sperm banking.

3.5. Identifying and Analyzing Factors Associated with Barriers to Sperm Banking

Bivariate analyses, including Independent T-tests and Fisher Exact tests, were conducted to assess the relationship between potential factors and barriers to sperm banking, as outlined in Table 2. Significantly, ethnicity and religious affiliation exhibited associations with barriers to sperm banking, with a p-value less than 0.05. Specifically, Malay patients demonstrated a decreased likelihood of engaging in sperm banking compared to Chinese and Borneos. Additionally, individuals adhering to the Islamic faith were less inclined to utilize sperm banking services compared to those practicing Buddhism and Christianity. However, variables such as age at diagnosis, educational attainment, income, marital status, and the presence of children at the time of diagnosis did not exhibit any statistically significant associations with barriers to sperm banking.

Table 2.

Summarizes the association between factors and barriers linked to sperm banking.

4. Discussion

This study marks the inaugural investigation in Malaysia examining the adoption of sperm banking among people with testicular cancer diagnosis. The significance of this research is underscored by the fact that testicular cancer patients boast an average 10-year survival rate of 98%, making it the most prevalent cancer in men of reproductive age. Given the potential gonadotoxicity of cancer treatments, awareness regarding fertility preservation becomes paramount for informed decision-making. Notably, international reports indicate a high rate of underutilization of sperm banking, with only 24% of testicular cancer patients opting for this measure before treatment [15]. Furthermore, studies reveal that merely half of male patients report being presented with the opportunity to bank sperm at the time of diagnosis [16]. In our study, a mere 9.7% of patients elected to undergo sperm banking before commencing cancer treatment, reflecting a surprisingly low utilization rate.

Primary clinicians play a pivotal role in addressing awareness gaps and understanding barriers to sperm banking. A survey in the USA revealed that 91% of hematologists and oncologists concurred that sperm banking should be offered to all men at risk of infertility due to cancer treatment, yet 48% failed to discuss or mention the option [16]. Similarly, our findings parallel this trend, with 41.1% of patients reporting not being offered the choice of sperm banking before treatment initiation. Reasons cited for not opting for sperm banking included lack of health insurance and being under 18 years old [14,16].

In Malaysia, households are classified into three income groups: the bottom 40% (B40), the middle 40% (M40), and the top 20% (T20). According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), in 2022, the average monthly incomes for these groups are as follows: RM3401 (approximately 725 USD) for B40, RM7961 (approximately 1641 USD) for M40, and RM19,752 (approximately 4214 USD) for T20. Consequently, the financial implications of sperm banking become a crucial factor to consider, as it requires a long-term commitment rather than a one-time expense. The cost of sperm banking varies depending on the facility. At The Chancellor Tuanku Muhriz Hospital (HCTM), which benefits from government subsidies, the initial session costs approximately RM500 (approximately 105 USD), with storage fees of around RM250 (approximately 53 USD) every two years. In contrast, private fertility centers charge RM950 (approximately 200 USD) for the initial session, with annual storage fees ranging from RM1000 to RM1300 (approximately 210 to 274 USD). For 21.4% of our participants, the cost is a significant deterrent. Despite these costs, sperm banking in Malaysia remains a more economical option compared to surgical sperm retrieval, which exceeds RM5000 (approximately 1050 USD) due to additional charges for anesthesia, procedure-related expenses, and hospital fees. Intrauterine insemination (IUI) costs around RM1600 (approximately 340 USD) per session, while in vitro fertilization (IVF) ranges from RM16,000 to RM18,000 (approximately 3400 to 3825 USD). Health insurance plans in Malaysia do not cover the costs of fertility treatments. To assist Malaysians with funding for fertility treatments, the government launched the Employees Provident Fund (EPF)’s latest health withdrawal facility in 2020. This initiative allows eligible members to make withdrawals from their EPF accounts specifically for fertility treatment. The EPF, established in 1951 under the Employees Provident Fund Act 1991, is a provident fund designed to help the Malaysian workforce save for retirement [17].

In the context of Malaysia, where Islam is the official religion, concerns regarding gamete and tissue cryopreservation among unmarried Muslim testicular cancer patients arise due to Islamic perspectives. Our study aligns with this concern, revealing that Malay Muslim patients were less inclined to utilize sperm banking compared to other ethnic groups. However, recent literature reviews support the permissibility of gamete cryopreservation in Islam, emphasizing its fundamental role for reproductive-age cancer patients. In 1981, the “Muzakarah” Fatwa Committee of the National Council for Islamic Religious Affairs in Malaysia declared sperm banking to be illegal in Islam. However, between 2017 and 2019, several international Fatwas allowed cryopreservation for cancer patients, as long as it is used for fertilization with a legally married partner. By 2020, the unpublished “Muzakarah” of the Islamic Religious Office in the Federal Territories of Kuala Lumpur had embraced the recommendations of Dar al-Ifta’ al-Misriyyah, which support the necessity of oocyte and sperm cryopreservation for cancer patients prior to chemotherapy or radiotherapy, allowing this procedure even before marriage [18]. Disseminating this information during counseling sessions is imperative to dispel misunderstandings.

A multifaceted approach is recommended to ameliorate the underutilization of sperm banking among testicular cancer patients in Malaysia. Efforts should focus on elevating awareness through targeted educational initiatives for both healthcare professionals and patients, emphasizing the importance of discussing fertility preservation options, including sperm banking, at the time of cancer diagnosis. Strategies to enhance affordability and accessibility, such as financial assistance programs and insurance coverage, should be explored to mitigate economic barriers. Additionally, it is advisable for the government to establish sperm banking services in every public tertiary center in each state of Malaysia or partner with local fertility clinics to ensure patients have easy access, affordable prices, and no delays in treatment. Cultural sensitivity is crucial, necessitating the development of materials addressing concerns related to gamete cryopreservation in line with Islamic perspectives. A targeted health campaign should involve the Islamic Religious Office of Malaysia to educate Malay Muslims about the permissibility of sperm banking for cancer patients, even before marriage. Furthermore, structured continuing medical education (CME) programs, such as workshops on artificial reproductive techniques and certification in counseling simulation training, should be provided to oncologists and urologists to enhance their competency in discussing and facilitating fertility preservation. By implementing these changes, we aim to increase the utilization of sperm banking and improve patient care.

The study faces a significant limitation due to the scarcity of participants, which is a direct result of the rare incidence of testicular cancer in Malaysia. Over a five-year period, from 2019 to 2023, only a total of 102 cases were documented across two major urology centers in the country: Hospital Sultanah Aminah and Sarawak General Hospital. This scarcity is compounded by the reliance of both hospitals on manual medical record systems, which occasionally pose challenges in accessing accurate contact information. Consequently, some phone numbers were found to be incorrect or outdated, making it difficult to reach certain patients. Moreover, the reluctance of some patients to participate in the survey further exacerbates the challenge of obtaining a sufficient sample size. Therefore, this study is subject to bias due to an underestimated sample size. Another limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design. Given that potential factors and the utilization of sperm banking were measured simultaneously, we were only able to explore associations rather than establish direct causal relationships between these potential factors and the utilization of sperm banking.

Sperm banking stands out as a cost-effective and invaluable strategy for preserving fertility in testicular cancer patients. Our findings underscore the critical importance of healthcare providers taking an active role in offering this option to patients before initiating treatment. By ensuring comprehensive and accessible information, addressing concerns, and fostering open communication, providers empower patients to make informed decisions about safeguarding their reproductive potential. The proactive promotion of sperm banking in the pre-treatment phase is not only a practical and ethical approach but also a fundamental step toward enhancing the overall well-being of testicular cancer survivors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.T., N.M.S. and S.O.; methodology, J.R.T.; software, J.R.T.; validation, Y.K.G., C.M.L., M.S.L. and G.C.T.; formal analysis, J.R.T.; investigation, J.R.T., C.M.L. and N.M.S.; resources, J.R.T. and C.M.L.; data curation, J.R.T. and N.M.S.; writing-original draft preparation, J.R.T.; writing-review and editing, Y.K.G. and C.M.L.; visualization, Y.K.G. and C.M.L., supervision, Y.K.G., C.M.L., S.O., M.S.L. and G.C.T.; project administration, J.R.T., funding acquisition, Y.K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was registered with the National Medical Research Registry (NMRR) [NMRR ID-22-00816-FQW (IIR)]. Research ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC), Ministry of Health, Malaysia, on 28 April 2023 prior to data collection (Reference: 22-00816-FQW(3)).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided verbal informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to privacy. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to J.R.T.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharlip, I.D.; Jarow, J.P.; Belker, A.M.; Lipshultz, L.I.; Sigman, M.; Thomas, A.J.; Schlegel, P.N.; Howards, S.S.; Nehra, A.; Damewood, M.D.; et al. Best practice policies for male infertility. J. Urol. 2002, 167, 2138–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, P.M.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Vistisen, K.; Rørth, M.; Giwercman, A. Semen quality and reproductive hormones before and after orchiectomy in men with testicular cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 161, 822–826. [Google Scholar]

- GLOBOCAN. New Global Cancer Data. 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/458-malaysia-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Malaysia National Cancer Registry Report 2012–2016. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/Penerbitan/Laporan/Umum/2012-2016%20(MNCRR)/MNCR_2012-2016_FINAL_(PUBLISHED_2019).pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Rives, N.; Perdrix, A.; Hennebicq, S.; Saïas-Magnan, J.; Melin, M.-C.; Berthaut, I.; Barthélémy, C.; Daudin, M.; Szerman, E.; Bresson, J.-L.; et al. The semen quality of 1158 men with testicular cancer at the time of cryopreservation: Results of the French National CECOS Network. J. Androl. 2012, 33, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brydøy, M.; Fosså, S.D.; Klepp, O.; Bremnes, R.M.; Wist, E.A.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Dahl, O.; for the Norwegian Urology Cancer Group III Study Group. Paternity and testicular function among testicular cancer survivors treated with two to four cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Eur. Urol. 2010, 58, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brydøy, M.; Fosså, S.D.; Klepp, O.; Bremnes, R.M.; Wist, E.A.; Bjøro, T.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Dahl, O.; Norwegian Urology Cancer Group (NUCG) III Study Group. Sperm counts and endocrinological markers of spermatogenesis in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talib, J.; Mamat, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Mohamad, Z. Analysis on Sex Education in Schools Across Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 59, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yusof, T.A. Malaysia’s First Oncofertility Centre Gives Hope for Cancer Patients. News Straits Times, Kuala Lumpur. 2020. Available online: https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/08/619677/malaysias-first-oncofertility-centre-gives-hope-cancer-patients (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Pusat Reproduktif Termaju HCTM. Available online: https://hctm.ukm.my/mac/ (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Department Of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal. Available online: https://v1.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Logan, S.; Perz, J.; Ussher, J.; Peate, M.; Anazodo, A. Systematic review of fertility-related psychological distress in cancer patients: Informing on an improved model of care. Psycho Oncol. 2019, 28, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, K.; Nangia, A.K.; Dupree, J.M.; Smith, J.F.; Mehta, A. Fertility preservation for men with testicular cancer: Is sperm cryopreservation cost effective in the era of assisted reproductive technology? Urol. Oncol. 2018, 36, 92.e1–92.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenburg, D.W.; Brames, M.J.; Case-Eads, S.; Einhorn, L.H. Utilization of sperm banking and barriers to its use in testicular cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2015, 23, 2763–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, J.A.; Ahmed, K.; Yap, T.; Minhas, S.; Shabbir, M. Fertility managment in testicular cancer: The need to establish a standardized and evidence-based patient-centric pathway. BJU Int. 2019, 123, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schover, L.R.; Brey, K.; Lichtin, A.; Lipshultz, L.I.; Jeha, S. Oncologists’ attitudes and practices regarding banking sperm before cancer treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 1890–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Employees Provident Fund Offical Website. Raja Permaisuri Agong Graces the Launch of EPF’s Health Withdrawal for Fertility Treatment. 2020. Available online: https://www.kwsp.gov.my/w/raja-permaisuri-agong-graces-the-launch-of-epf-s-health-withdrawal-for-fertility-treatment (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Ahmad, M.F.; Ghani, N.A.R.N.A.; Abu, M.A.; Karim, A.K.A.; Shafiee, M.N. Oncofertility in Islam: The Malaysian Perspective. Front. Reprod. Health 2021, 3, 694990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).