Facing Change through Diversity: Resilience and Diversification of Plant Management Strategies during the Mid to Late Holocene Transition at the Monte Castelo Shellmound, SW Amazonia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.2. Regional Context

2. Southwestern Amazon Culture and Landscape Dynamics

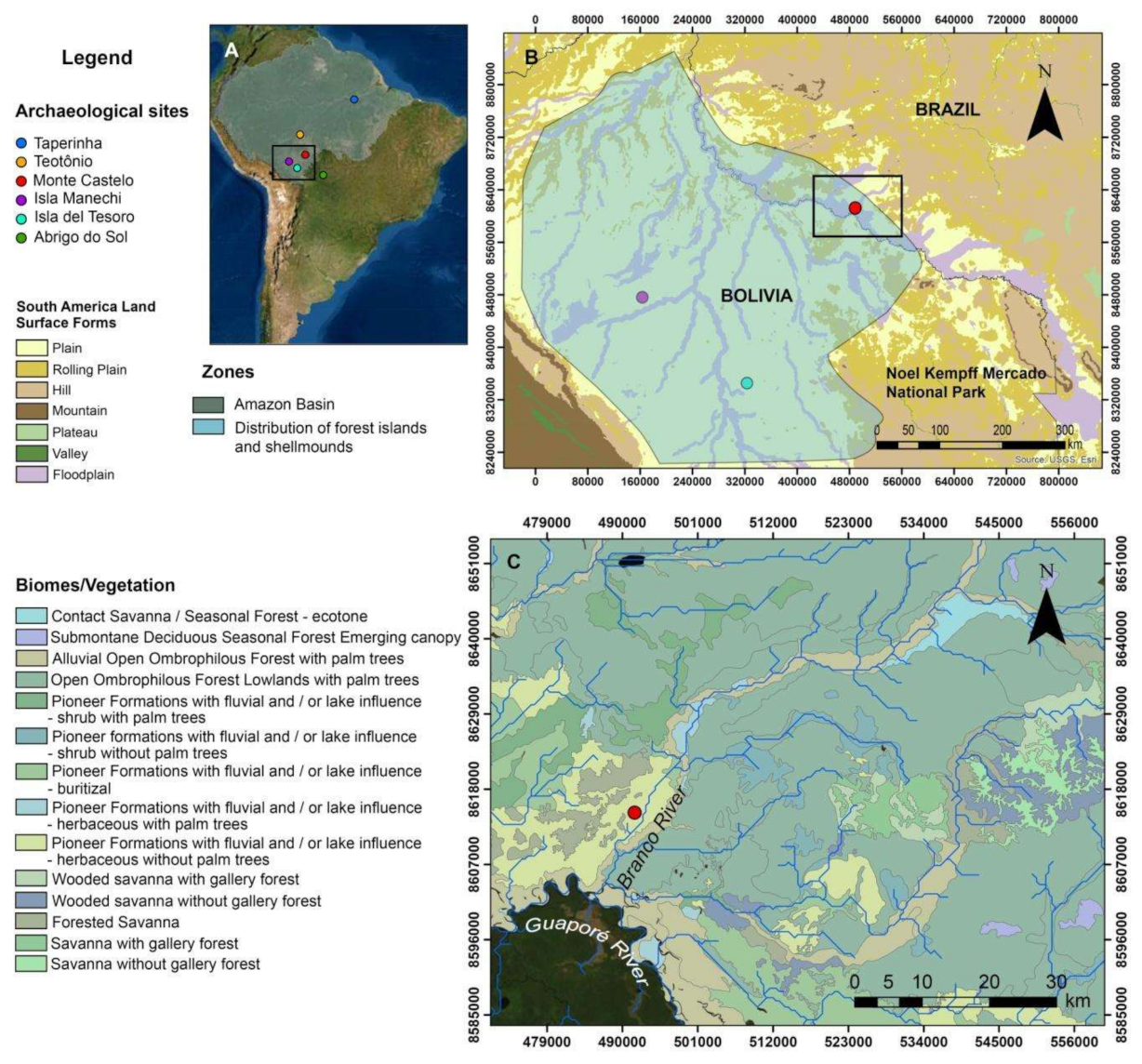

2.1. The Monte Castelo Shellmound

2.2. Monte Castelo in Its Past and Present Environmental Setting(s)

2.3. Mobility, Seasonality, and Cultural Interactions: The Evidence So Far

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Macrobotanical and Phytolith Analysis of Sediments

3.1.1. Sampling

3.1.2. Extraction and Identification

3.2. Starch Grain and Phytolith Analysis of Ceramic Residues

Extraction and Identification

4. Results

4.1. Macrobotanical and Phytolith Analysis of Sediments

4.1.1. General Observations

4.1.2. Cupim Package (Layers U–S)

4.1.3. Sinimbu Package (Layers R–J)

4.1.4. Sinimbu–Bacabal Transition (Layers I–E)

4.1.5. Bacabal Package (Layers D–A)

4.2. Ceramic Residue Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Antiquity: The Long-Term History of Plant and Landscape Management and Its Implication to Historicity

5.2. Diversification: Of Plants and Ecosystems in an Ecological Mosaic

5.3. Continuity vs. Discontinuity: Entangling Plants, Cultural, and Climatic Changes

6. Conclusions

- Despite dramatic, climate-induced changes in local hydrological regimes and the distribution of exploited plant resources that occurred during the site’s occupation, at no point do we recognize any abrupt changes to the processes by which humans acquired their food, emphasizing the resilience of Middle Holocene subsistence strategies in the face of changing environments.

- People continuously exploited a diverse range of cultivated, managed, and potentially wild species, thus there is no moment that could be interpreted as a transition to “agriculture” or an intensification of food production, but rather a tendency towards progressively diversified food assemblages.

- Occupations seem to have been perennial (i.e., distributed across both wet and dry seasons), but not permanent, throughout the site’s history. The range of ecosystems represented by their plant remains, particularly in the Bacabal period, suggests that the site formed part of much larger human territories, as it does today for local indigenous groups.

- These observations lead us to reject traditional forms of dividing long-term history in the Amazon (particularly the existence of a Formative stage), as well as the supposed relationships between plant cultivation and settlement permanence.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roosevelt, A.; Costa, M.; Machado, C.; Michab, M.; Mercier, N.; Valladas, H.; Feathers, J.; Barnett, W.; Imazio da Silveira, M.; Henderson, A.; et al. Paleoindians Cave-Dweelers in the Amazon: The peopling of Americas. Science 1996, 272, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. Algumas Culturas Ceramistas, do Noroeste do Pantanal do Guaporé à Encosta e Altiplano Sudoeste do Chapadão dos Parecis. Origem, Difusão/Migração e Adaptação—Do Noroeste da América do Sul ao Brasil. Linguística Antropológica 2013, 5, 335–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcote-Rios, G.; Cabrera-Becerra, G.; Mahecha-Rubio, D.; Franky-Calvo, C.; Cavalier-F, I. Las Palmas entre los grupos cazadores-recolectores de la Amazonia Colombiana. Caldasia 1998, 20, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shock, M.; Moraes, C. A floresta é o domus: A importância das evidências arqueobotânicas e arqueológicas das ocupações humanas amazônicas na transição Pleistoceno/Holoceno. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Ciências Humanas 2019, 14, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lombardo, U.; Iriarte, J.; Hilbert, L.; Ruiz-Pérez, J.; Capriles, J.; Veit, H. Early Holocene crop cultivation and landscape modification in Amazonia. Nature 2020, 581, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, J.; Robinson, M.; Gregorio de Souza, J.; Barbosa, A.; Silva, F.; Nakahara, F.; Ranzi, A.; Aragao, L. Geometry by Design: Contribution of Lidar to the Understanding of Settlement Patterns of the Mound Villages in SW Amazonia. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 2020, 3, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watling, J.; Shock, M.; Mongeló, G.; Akmeida, F.O.; Kater, T.; Oliveira, P.; Neves, E.G. Direct archaeological evidence for Southwestern Amazonia as an early plant domestication and food production centre. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maezumi, S.Y.; Alves, D.; Robinson, M.; de Souza, J.G.; Levis, C.; Barnett, R.L.; De Oliveira, E.A.; Urrego, D.; Schaan, D.; Iriarte, J. The legacy of 4,500 years of polyculture agroforestry in the eastern Amazon. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Watling, J.; Almeida, F.; Kater, T.; Zuse, S.; Shock, M.; Mongeló, G.; Bespalez, E.; Santi, J.R.; Neves, E.G. Arqueobotânica de ocupações ceramistas na Cachoeira do Teotônio. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Ciências Humanas 2020, 15, 20190075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, L.P. Arqueobotânica e Mudanças Socioeconômicas Durante o Holoceno Médio no Sudoeste da Amazônia. Master’s Thesis, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Furquim, L.; Neves, E.; Watling, J.; Shock, M. O testemunho da arqueologia sobre a agrobiodiversidade, as florestas antrópicas e o manejo do fogo nos Últimos 14,000 anos de anos de história indígena na Amazônia Antiga. DiagnÓstico Povos IndÍgenas e Comunidades Locais Tradicionais no Brasil: ContribuiÇÕes para a Biodiversidade, AmeaÇas e PolÍticas PÚblicas. in press. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/projetocnpq421752/contato?authuser=0 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Almeida, F.O.; Kater, T. As cachoeiras como bolsões de histórias dos grupos indígenas das terras baixas sul-americanas. Rev. Bras. Hist. 2017, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowser, B.; Zedeno, M.N. The Archaeology of Meangfull Places; University of Utah: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2009; 222p. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio de Souza, J.; Robinson, M.; Maezumi, S.; Capriles, J.; Hoggarth, J.; Lombardo, U.; Novello, V.F.; Apaéstegui, J.; Whitney, B.; Urrego, D.; et al. Climate change and cultural resilience in late pre-Columbian Amazonia. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo-Kalin, M.; Riris, P. Did Amazonian pre-Columbian populations reach carrying capacity during the Late Holocene? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 376, 20190715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riris, P.; Arroyo-Kalin, M. Widespread population decline in South America correlates with mid-Holocene climate change. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roosevelt, A. Moundbuilders of the Amazon: Geophysical Archaeology on Marajo Island, Brazil; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; 480p. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, E. Village Fissioning in Amazonia: A critique of monocausal determinism. Revista do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia 1995, 5, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, E.G. Was agriculture a key productive activity in pre-Colonial Amazon. In Human-Environment Interactions: Current and Future Decisions; Brondízio, E.S., Moran, E.F., Eds.; Springerp: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 371–388. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-94-007-4780-7 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Neves, E.G. Não existe neolítico ao sul do Equador: As primeiras cerâmicas amazônicas e sua falta de relação com a agricultura. In Cerâmicas Arqueológicas da Amazônia: Rumo a Uma Nova Síntese; Lima, B.B., Ed.; IPHAN: Belém, PA, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fausto, C. Inimigos Fiéis. História, Guerra e Xamanismo na Amazônia; EDUSP: São Paulo, Brazil, 2001; 592p. [Google Scholar]

- Heckenberger, M. War and Peace in the Shadow of Empire: Sociopolitical Change in the Upper Xingu of Southeastern Amazonia, AD 1400-2000; Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Heckenberger, M. The Ecology of Power: Culture, Place and Personhood in the Southern Amazon, AD 1000-2000; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–404. [Google Scholar]

- Rival, L.M. Trekking Through History; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/riva11844 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Costa, L. Worthless Movement: Agricultural Regression and Mobility. Tipiti 2009, 7, 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, B. Gatherer-Hunter to Farmer: A Social Perspective. World Archaeol. 1978, 10, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckenberger, M.; Petersen, J.; Neves, E. Village Size and Permanence in Amazonia: Two Archaeological Examples from Brazil. Lat. Am. Antiq. 1999, 10, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastorf, C. 3. Domesticated Food and Society in Early Coastal Peru: Studies in the Neotropical Lowlands. In Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology; Balée, W., Erickson, C., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hastorf, C.A. The cultural life of early domestic plant use. Antiquity 1998, 72, 773–782. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/cultural-life-of-early-domestic-plant-use/B5D8FEB819A009BE67FF4A9E780500F2 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Levis, C.; Flores, B.M.; Moreira, P.A.; Luize, B.G.; Alves, R.P.; Franco-Moraes, J.; Lins, J.; Konings, E.; Peña-Claros, M.; Bongers, F.; et al. How People Domesticated Amazonian Forests. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 5, 171. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fevo.2017.00171 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levis, C.; Costa, F.R.C.; Bongers, F.; Peña-Claros, M.; Clement, C.R.; Junqueira, A.B.; Neves, E.G.; Tamanaha, E.K.; Figueiredo, F.O.G.; Salomão, R.P.; et al. Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on Amazonian forest composition. Science 2017, 355, 925–931. Available online: http://www.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/science.aal0157 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Kalin, M. Human niche construction and population growth in pre-Columbian Amazonia. Archaeol. Int. 2017, 20, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C. O determinismo agrícola na arqueologia amazônica. Estud. Avançados. 2015, 29, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neves, E.; Heckenberger, M. The Call of the Wild: Rethinking Food Production in Ancient Amazonia. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2019, 48, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ingold, T. The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeol. 1993, 25, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. The Perceptions of Environment. Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill; Taylor & Francis Ltd: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; 460p. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, C.; Levis, C.; Franco-Moraes, J.; Junqueira, A. Domesticated Nature: The Culturally Constructed Niche of Humanity; Springer Nature: Basingstoke, UK, 2020; pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, C.; Denevan, W.; Heckenberger, M.; Junqueira, A.; Neves, E.; Teixeira, W.; Woods, W.I. The domestication of Amazonia before European conquest. Proc. B R. Soc. 2015, 282, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, B.D. A Cultural Niche Construction Theory of Initial Domestication. Biol. Theory 2011, 6, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meggers, B.; Miller, E. Hunter-Gatherers in Amazonia during the Pleistocene-Holocene Transition. In Under the Canopy the Archaeology of Tropical Rainforests; Mercader, J., Ed.; Rudges University Press: London, UK, 2003; pp. 291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E. História da Cultura Indígena do Alto Médio-Guaporé (Rondônia e Mato Grosso). Ph.D. Thesis, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, E. Sob os Tempos do Equinócio: Oito mil anos de História na Amazônia Central (6.500 AC–1.500 DC). Ph.D. Thesis, USP, São Paulo, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, A.; Neves, W.; Piló, L.; Atui, J.P. Holocene Dryness and Human Occupation in Brazil During the “Archaic Gap”. Quat. Res. 2005, 64, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, D.R.; Pearsall, D.M. The Origins of Agriculture in the Lowland Neotropics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, U.; Szabo, K.; Capriles, J.; May, J.-H.; Amelung, W.; Hutterer, R.; Lehndorff, E.; Plotzki, A.; Veit, H. Early and Middle Holocene Hunter-Gatherer Occupations in Western Amazonia: The Hidden Shell Middens. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capriles, J.M.; Lombardo, U.; Maley, B.; Zuna, C.; Veit, H.; Kennett, D.J. Persistent Early to Middle Holocene tropical foraging in southwestern Amazonia. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav5449. Available online: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/4/eaav5449.abstract (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caldarelli, S.; Kipnis, R. A ocupação pré-colonial da Bacia do Rio Madeira: Novos dados e problemáticas associadas. Especiaria Cadernos de Ciências Humanas 2017, 17, 229–289. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, F.; Mongeló, G. Introducao. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Ciências Humanas 2020, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese, F.; Zimpel, C.; Neves, E. What do Amazonian Shellmounds Tell Us About the Long-Term Indigenous History of South America. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Calo, C.M.; Rizzutto, M.A.; Carmello-Guerreiro, S.M.; Dias, C.S.B.; Watling, J.; Shock, M.P.; Zimpel, C.A.; Furquim, L.P.; Pugliese, F.; Neves, E.G. A correlation analysis of Light Microscopy and X-ray MicroCT imaging methods applied to archaeological plant remains’ morphological attributes visualization. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, D.R. The origins of plant cultivation and domestication in the New World tropics: Patterns, process, and new developments. Curr. Anthropol. 2011, 52, S453–S470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, C.R.; Rodrigues, D.P.; Alves-Pereira, A.; Mühlen, G.S.; Cristo-Araújo, M.d.; Moreira, P.A.; Lins, J.; Reis, V.M. Crop domestication in the upper Madeira River basin. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 2016, 11, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugger, S.O.; Gobet, E.; van Leeuwen, J.F.N.; Ledru, M.-P.; Colombaroli, D.; van der Knaap, W.O.; Lombardo, U.; Escobar-Torrez, K.; Finsinger, W.; Rodrigues, L.; et al. Long-term man–environment interactions in the Bolivian Amazon: 8000 years of vegetation dynamics. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 132, 114–128. Available online: https://app.dimensions.ai/details/publication/pub.1022417855 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Bush, M.; Correa-Metrio, A.; Van Woesik, R.; Shadik, C.; Mcmichael, C. Human disturbance amplifies Amazonian El Niño-Southern Oscillation signal. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 3181–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistler, L.; Maezumi, S.Y.; Gregorio de Souza, J.; Przelomska, N.A.S.; Costa, F.; Smith, O.; Loiselle, H.; Ramos-Madrigal, J.; Wales, N.; Ribeiro, E.R.; et al. Multiproxy evidence highlights a complex evolutionary legacy of maize in South America. Science 2018, 362. Available online: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/362/6420/1309.abstract (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilbert, L.; Neves, E.G.; Pugliese, F.; Whitney, B.S.; Shock, M.; Veasey, E.; Zimpel, C.A.; Iriarte, J. Evidence for mid-Holocene rice domestication in the Americas. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1693–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, E.G. A tale of three species or the ancient soul of tropical forests. In Tropical Forest Conservation: Long-Term Processes of Human Evolution, Cultural Adaptations and Consumption Patterns; UNESCO: London, UK, 2016; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Hastorf, C.; Poper, V. Current Paleoethnobotany Analytical Methods and Cultural Interpretations of Archaeologycal Plant Remains; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989; 243p, Available online: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo3774985.html (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Johannessen, S. Plant Remains and Culture Change: Are Paleoethnobotanical Data Better Than We Think. In Current Paleoethnobotany Analytical Methods and Cultural Interpretarions of Archaeological Plant Remains; Hastorf, C.A., Poper, V.S., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, T.; Hastorf, C. Environmental Interpretation of Archaeological Charcoal. In Current Paleoethnobotany Analytical Methods and Cultural Interpretarions of Archaeological Plant Remains; Hastorf, C.A., Poper, V.S., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Caromano, C. Fogo no Mundo das Águas. Antracologia no Sítio Hatahara, Amazônia Central. Ph.D. Thesis, Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, USP, São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Caromano, C.; Cascon, L.; Murrieta, R. A Roça Asurini e o Fogo Bonito de Aí. Habitus 2016, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asch, D.; Sidell, N. Archaeological Plant Remains: Applications to Stratigraphic Analysis. In Current Paleoethnobotany Analytical Methods and Cultural Interpretarions of Archaeological Plant Remains; Hastorf, C.A., Poper, V.S., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bandeira, A.; Chahud, A.; Ferreira, I.; Pacheco, M. Mobilidade, subsistência e apropriação do ambiente: Contribuições da zooarqueologia sobre o Sambaqui do Bacanga, São Luís, Maranhão. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Ciências Humanas 2016, 11, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcos, J. Un Sítio Llamado Real Alto; Universidad Internacional del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zimpel, C.A. A Fase Bacabal e Seus Correlatos Arqueológicos na Amazônia; USP: São Paulo, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Prestes-Carneiro, G.; Béarez, P.; Pugliese, F.; Shock, M.P.; Zimpel, C.A.; Pouilly, M.; Neves, E.G. Archaeological history of Middle Holocene environmental change from fish proxies at the Monte Castelo archaeological shell mound, Southwestern Amazonia. Holocene 2020, 30, 1606–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, F.; Zimpel, C.; Neves, E. Los concheros de la Amazonía y la historia indígena profunda de América del Sur. In Las Siete Maravillas de la Amazonía Precolombina; IV Encuentro Internacional de Arqueología Amazónica; Bonner Altamerika-Sammlung und Studien; Rostain, B., Ed.; Plural Editores: La Paz, Bolivia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, C.J. La cerámica de los afluentes del Guaporé en la colección de Erland von Nordenskiöld. Zeitschrift für Archäologie Außereuropäischer Kulturen 2011, 4, 311–340. [Google Scholar]

- Prümers, H.; Jaimes Betancourt, C. 100 Años de Investigación Arqueológica en los Llanos de Mojos. Arqueoantropológicas 2014, 4, 11–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese, F.; Santos, R.; Zimpel, C.; da Silva, C.A.; Prestes-Carneiro, G.; Shock, M.; Hermenegildo, T.; Mongeló, G.; Furquim, L.; Watling, J.; et al. An Independent Centre of Early Ceramic Production in SW Amazonia. Antiquity 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- IBDF. Reserva Biológica do Guaporé. Plano de Manejo; IBDF: Brasília, Brazil, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Burbridge, R.; Mayle, F.; Killeen, T. Fifty-thousand-year vegetation and climate history of Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, Bolivian Amazon. Quat. Res. 2004, 61, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayle, F.E.; Langstroth, R.P.; Fisher, R.A.; Meir, P. Long-term forest-savannah dynamics in the Bolivian Amazon: Implications for conservation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 362, 291–307. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17255037 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carson, J.F.; Whitney, B.S.; Mayle, F.E.; Iriarte, J.; Prümers, H.; Soto, J.D.; Watling, J. Environmental impact of geometric earthwork construction in pre-Columbian Amazonia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10497–10502. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25002502 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayle, F.E.; Burbridge, R.; Killeen, T.J. Millennial-Scale Dynamics of Southern Amazonian Rain Forests. Science 2000, 290, 2291–2294. Available online: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/290/5500/2291.abstract (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, R.; Mayle, F. Impact of mid- to late Holocene precipitation changes on vegetation across lowland tropical South America: A paleo-data synthesis. Quat. Res. 2017, 89, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lombardo, U.; Rodrigues, L.; Veit, H. Alluvial plain dynamics and human occupation in SW Amazonia during the Holocene: A paleosol-based reconstruction. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2018, 180, 30–41. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277379117306042 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lombardo, U.; Ruiz-Pérez, J.; Rodrigues, L.; Mestrot, A.; Mayle, F.; Madella, M.; Szidat, S.; Veit, H. Holocene land cover change in south-western Amazonia inferred from paleoflood archives. Glob. Planet Chang. 2019, 174, 105–114. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921818118303072 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pessenda, L.C.R.; Boulet, R.; Aravena, R.; Rosolen, V.; Gouveia, S.E.M.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Lamotte, M. Origin and dynamics of soil organic matter and vegetation changes during the Holocene in a forest-savanna transition zone, Brazilian Amazon region. Holocene 2001, 11, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessenda, L.C.R.; Gouveia, S.E.M.; Aravena, R.; Gomes, B.M.; Boulet, R.; Ribeiro, A.S. 14C Dating and Stable Carbon Isotopes of Soil Organic Matter in Forest–Savanna Boundary Areas in the Southern Brazilian Amazon Region. Radiocarbon 1997, 40, 1013–1022. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/14c-dating-and-stable-carbon-isotopes-of-soil-organic-matter-in-forestsavanna-boundary-areas-in-the-southern-brazilian-amazon-region/102BDC8E22CE0BE3644F00A49F7CBD9D (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, P.A.; Seltzer, G.O.; Fritz, S.C.; Dunbar, R.B.; Grove, M.J.; Tapia, P.M.; Cross, S.L.; Rowe, H.D.; Broda, J.P. The history of South American tropical precipitation for the past 25,000 years. Science 2001, 291, 640–643. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11158674 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carneiro da Cunha, M. Antidomestication in the Amazon. Swidden and its foes. HAU J. Ethnogr. Theory 2019, 9, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prümers, H. Sitios prehispánicos con zanjas en Bella Vista, Provincia Iténez, Bolivia. In Antes de Orellana Actas del 3er Encuentro Internacional de Arqueología Amazônica; Rostain, S.M., Ed.; IFEA, FLASCO, MCCTH, SENESCYT: Quito, Ecuador, 2014; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Calo, C.M.; Rizzutto, M.A.; Watling, J.; Furquim, L.; Shock, M.P.; Andrello, A.C.; Appoloni, C.R.; Freitas, F.O.; Kistler, L.; Zimpel, C.A.; et al. Study of plant remains from a fluvial shellmound (Monte Castelo, RO, Brazil) using the X-ray MicroCT imaging technique. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2019, 26, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearsall, D.M. Paleoethnobotany: A Handbook of Procedures, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Piperno, D.R. Phytoliths: A Comprehensive Guide for Archaeologists and Paleoecologists; Altamira Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Juggins, S. C2. 2010. Available online: https://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/stephen.juggins/software/C2Home.htm (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Coil, J.; Korstanje, M.; Archer, S.; Hastorf, C. Laboratory goals and considerations for multiple microfossil extraction in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2003, 30, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Shock, M.; Neves, E.; Lima, H.; Scheel-Ybert, R. Recovering macroremains in Amazonian archaeological sites: A new methodological proposal for archaeobotanical studies. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Ciências Humanas 2013, 8, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.M.d.; Shock, M.; Neves, E.; Scheel-Ybert, R. Vestígios Macrobotânicos Carbonizados na Amazônia Central: O que eles nos dizem sobre as plantas na Pré-História? Cadernos do LEPAARQ 2016, 13, 366–385. [Google Scholar]

- Bremond, L.; Alexandre, A.; Peyron, O.; Joel, G. Definition of grassland biomes from phytoliths in West Africa. J. Biogeogr. 2008, 35, 2039–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, U.; Prümers, H. Pre-Columbian human occupation patterns in the eastern plains of the Llanos de Moxos, Bolivian Amazonia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 1875–1885. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0305440310000749 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Bozarth, S.R. Diagnostic Opal Phytoliths from Pods of Selected Varieties of Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris). Am. Antiq. 1990, 55, 98–104. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/diagnostic-opal-phytoliths-from-pods-of-selected-varieties-of-common-beans-phaseolus-vulgaris/CCC26E761EE08E274A2E7BAD2B73C3F6 (accessed on 20 January 2017). [CrossRef]

- Morcote-Ríos, G.; Mahecha, D.; Franky, C. Recorrido en el tiempo: 12000 años de ocupación de la Amazonia. In Universidad y Territorio; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Roosevelt, A.C. The Amazon and the Anthropocene: 13,000 years of human influence in a tropical rainforest. Anthropocene 2014, 4, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, I. Early Cultures and Human Ecology in South Coastal Guatemala. In Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology; Coes, M., Flannery, K., Eds.; Smithsonian Scholarly Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Mongeló, G. Ocupações humanas do Holoceno inicial e médio no sudoeste amazônico. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Ciências Humanas 2020, 15. Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1981-81222020000200901&tlng=pt (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Miller, E. Arqueologia nos Empreendimentos Hidreléctricos da Electronorte; RO: Porto Velho, Brazil, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fausto, C.; Neves, E.G. Was there ever a Neolithic in the Neotropics? Plant familiarisation and biodiversity in the Amazon. Antiquity 2018, 92, 1604–1618. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/was-there-ever-a-neolithic-in-the-neotropics-plant-familiarisation-and-biodiversity-in-the-amazon/C44CC4F0B44328D0903F285F77DF0EF8 (accessed on 23 February 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neves, E.; Almeida, F.; Watling, J. A arqueologia do alto Madeira no contexto arqueológico da Amazônia. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Ciências Humanas 2020, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozarth, S.R.; Price, K.; Woods, W.I.; Neves, E.G.; Rebellato, R. Phytoliths and Terra Preta: The Hatahara site example. In Amazonian Dark Earths: Will Sombroek’s Vision; Woods, W.I., Teixera, W.G., Lehmann, J., Steiner, C., WinklerPrins, A.M.G.A., Rebellato, L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Scheel-Ybert, R.; Boyadjian, C. Gardens on the coast: Considerations on food production by Brazilian shellmound builders. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2020, 60, 101211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.; DeBlasis, P.; Fish, S.; Fish, P. Sambaqui (Shell Mound) Societies of Coastal Brazil. In Handbook of South American Archaeology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Morcote-Rios, G.; Bernal, R. Remains of Palms (Palmae) at Archaeological Sites in the New World: A Review. Bot. Rev. 2011, 67, 309–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel-Ybert, R. Man and Vegetation in Southeastern Brazil during the Late Holocene. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2001, 28, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Lab Code | Cucurbita sp. | Dioscorea sp. | Dioscoreatrifida | Ipomoea batatas | Zea mays | Unidentified | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Damage | N | Damage | ||||||

| MC 1 | 1 | HO, FR | 1 | ||||||

| MC 2 | 1 | PF, FR, HO | 1 | ||||||

| MC 3 | 1 | 1* | HO | 2 | |||||

| MC 4 | 1 | 2* | C | 1 | C | 4 | |||

| MC 5 | 1 | 1* | 2 | FR | 1 | 5 | |||

| MC 6 | 1 | HP, C | 2 | G, C, HO, FR | 3 | ||||

| MC 7 | CONC | G, HO, C | CONC | ||||||

| MC 8 | 5 | G, HO, C | 5 | ||||||

| Species | Macro, Phytolith or Starch | Ecological Niche | Harvest Season | Cupim | Sinimbu | Transition | Bacabal | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | T | S | R | Q | P | O | N | M | L | K | J | I | H | G | F | E | D | C | B | A | ||||||

| FRUIT-BEARING PERENNIALS | Cosmopolitan species | Annonacae | p | Multiple | wet and dry | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Annonaceae cf. Annona sp. | m | Multiple | wet | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arecaceae | m, p | Multiple | wet and dry | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Arecaceae Astrocaryum sp. | m | Multiple | wet and dry | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Arecaceae Attalea sp. | m | Multiple | wet and dry | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arecaceaecf. Bactris sp. | m | Multiple | wet | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arecaceae Bactris/Astrocaryum sp. | p | Multiple | wet | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Arecaceae Euterpe/Oenocarpus sp. | p | Multiple | wet and dry | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Fabaceae | m | Multiple | wet and dry | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Species with specific habitats | Arecaceae Mauritia flexuosa | m | Gallery forest; SI savanna | wet | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Malpighiaceae Byrsonima sp. | m | Cerrado; open forest; SI savanna | wet and dry | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Anacardiaceae Anacardium sp. | m | Cerrado; open forest | wet and dry | X | X | X (cf) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Myrtaceae cf. Psidium sp. | m | Cerrado; open forest | wet and dry | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Rosaceae cf. Prunus sp. | m | Gallery forest; semi-dec forest | dry | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fabaceae cf. Mimosoideae | m | TF forest (semi-dec) | wet and dry | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lecythidaceae Bertholettiaexcelsa | m | TF forest (Ev, semi-dec) | wet | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Cannabaceae Celtis sp. | p | TF forest (Ev, semi- dec); cerrado | wet | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Burseraceae | p | TF forest (Ev, semi-dec) | wet | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Malvaceae Theobroma sp. | m | TF forest (Ev) | wet and dry | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moraceae cf. Ficus sp. | m | TF and SI forest (Ev) | wet | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ANNUAL HERBS | Poaceae Zea mays | m, p, s | Cultigen | dry | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Poaceae Oryza sp. | p (glume) | Cultigen | wet | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Cucurbitaceae Cucurbita sp. | p, s | Cultigen | dry | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Dioscoreaceae Dioscorea sp. | s | Cultigen | dry | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dioscoreatrifida | s | Cultigen | dry | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Convulvulaceae Ipomoea batatas | s | Cultigen | year round | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fabaceae Phaseolus sp. | p | Cultigen | dry | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Furquim, L.P.; Watling, J.; Hilbert, L.M.; Shock, M.P.; Prestes-Carneiro, G.; Calo, C.M.; Py-Daniel, A.R.; Brandão, K.; Pugliese, F.; Zimpel, C.A.; et al. Facing Change through Diversity: Resilience and Diversification of Plant Management Strategies during the Mid to Late Holocene Transition at the Monte Castelo Shellmound, SW Amazonia. Quaternary 2021, 4, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat4010008

Furquim LP, Watling J, Hilbert LM, Shock MP, Prestes-Carneiro G, Calo CM, Py-Daniel AR, Brandão K, Pugliese F, Zimpel CA, et al. Facing Change through Diversity: Resilience and Diversification of Plant Management Strategies during the Mid to Late Holocene Transition at the Monte Castelo Shellmound, SW Amazonia. Quaternary. 2021; 4(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat4010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleFurquim, Laura P., Jennifer Watling, Lautaro M. Hilbert, Myrtle P. Shock, Gabriela Prestes-Carneiro, Cristina Marilin Calo, Anne R. Py-Daniel, Kelly Brandão, Francisco Pugliese, Carlos Augusto Zimpel, and et al. 2021. "Facing Change through Diversity: Resilience and Diversification of Plant Management Strategies during the Mid to Late Holocene Transition at the Monte Castelo Shellmound, SW Amazonia" Quaternary 4, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat4010008

APA StyleFurquim, L. P., Watling, J., Hilbert, L. M., Shock, M. P., Prestes-Carneiro, G., Calo, C. M., Py-Daniel, A. R., Brandão, K., Pugliese, F., Zimpel, C. A., da Silva, C. A., & Neves, E. G. (2021). Facing Change through Diversity: Resilience and Diversification of Plant Management Strategies during the Mid to Late Holocene Transition at the Monte Castelo Shellmound, SW Amazonia. Quaternary, 4(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat4010008