Abstract

Collecting is a form of leisure, and even a passion, consisting of collecting, preserving and displaying objects. When we look for its origin in the literature, we are taken back to “the appearance of writing and the fixing of knowledge”, specifically with the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (7th century BC, Mesopotamia), and his fondness for collecting books, which in his case were in the form of clay tablets. This is not, however, a true reflection, for we have evidence of much earlier collectors. The curiosity and interest in keeping stones or fossils of different colors and shapes, as manuports, is as old as we are. For decades we have had evidence of objects of no utilitarian value in Neanderthal homes. Several European sites have shown that these Neanderthal groups treasured objects that attracted their attention. On some occasions, these objects may have been modified to make a personal ornament and may even have been integrated into subsistence activities such as grinders or hammers. Normally, one or two such specimens are found but, to date, no Neanderthal cave or camp has yielded as many as the N4 level of Prado Vargas Cave. In the N4 Mousterian level of Prado Vargas, 15 specimens of Upper Cretaceous marine fossils belonging to the Gryphaeidae, Pectinidae, Cardiidae, Pholadomyidae, Pleurotomariidae, Tylostomatidae and Diplopodiidae families were found in the context of clay and autochthonous cave sediments. During MIS 3, a group of Neanderthals transported at least fifteen marine fossils, which were collected from various Cretaceous units located in the surrounding area, to the Prado Vargas cave. The fossils, with one exception, show no evidence of having been used as tools; thus, their presence in the cave could be attributed to collecting activities. These activities could have been motivated by numerous tangible and intangible causes, which suggest that collecting activities and the associated abstract thinking were present in Neanderthals before the arrival of modern humans.

1. Introduction

More than a hundred years have passed since the reconstruction of the Neanderthal skeleton, recovered in 1908 in the Chapelle-aux-Saints by Marcellin Boule and the first distorted graphic representation by the artist Frantizek Kupka.

As is well known, the lesions presented by this individual, such as missing teeth, bone atrophy, and arthritis, among others, led to a damaged reconstruction and image, which presented the Neanderthals as disabled and as ape-like beings; in fact, what was recovered in this burial and in others told us that this adult Neanderthal, nicknamed “the old man”, had to be cared for until his death, since the multiple lesions he had suffered would not have allowed him to live a normal life (Tappen 1985) [1].

Little by little, research has progressed, and these groups are now acknowledged to have capacities and attitudes that were denied to them at the beginning of the 20th century. We know that they must have had a strong social cohesion and that they undoubtedly took care of the sick and the elderly. In addition, the disposition of his body; buried in a grave dug totally or partially by fellow Neanderthals and the rapid burial of the body demonstrate the burial’s intentionality (Rendu, et al., 2014) [2]. About twenty Neanderthal burials are known in Western Europe, defined on the basis of two criteria: the presence of a pit, and the rapid burial of the remains. All are associated with occupations at the same site as the burial, so it is quite possible that symbolic manifestations and economic patterns are firmly rooted in European Neanderthal territories.

However, the debate on Neanderthal capacities is open to this day. In 1982, seventy years after his discovery, Jolly and Plog argued that the old man of the Chapelle was cared for by other members of his group; for example, they must have chewed his food. In 1985, Tappen denied such evidence. In 2014, more than a hundred years after the discovery, Rendu and other researchers defended the burial and its connotations, while in 2015 Dibble attacked these conclusions, denying any evidence of a burial and reviving the debate on Neanderthal abilities.

Fortunately, the archaeological record continues to expand, as new findings and research confirm, with reliable data, aspects of the ways of life of the Neanderthal groups, such as their technological, hunting, linguistic, cognitive and symbolic abilities (Soressi and D’Errico 2007) [3].

Elements of personal adornment, objects with incisions or marks that are not associated with utilitarian purposes, pigments, artistic manifestations and funerary practices, among others, are aspects that were already installed in the European groups of the Late Pleistocene. Abstract thinking has not only been seen in Europe, but there are also examples of archaic Homo sapiens in southern Africa (Mc Brearty and Brooks 2000) [4].

In recent years, other elements have timidly appeared that are grouped under the heading of exotic elements or curiosities (Soressi and d’Errico 2007) [3] and aesthetic evidence. We are referring to a group of unmodified materials such as fossils that have been moved to habitation sites and whose interpretation poses a challenge to researchers.

In this study, we present the collection of fossils recovered in level 4 of the Prado Vargas cave (Navazo et al. 2021) [5], and we attempt, in conjunction with a review of other synchronous sites where there is news of the existence of fossils, to unravel the collecting zeal of the Neanderthals.

First Evidence of Collecting Activity

Where can we find the first evidence of collecting? The reddish jasper stone, which looks like a human face, was found in the Makapansgat Valley (South Africa) and which looks like a human face, was possibly collected by an Australopithecus africanus and taken to his cave (Bednarik 1998; Marquet and Lorblanchet, 2000, 2016) [6,7,8]. A few years ago, an engraved mussel shell was found on the island of Java by Dubois was discovered and was associated with Homo erectus (Joordens et al. 2014) [9]. Bead-like Jurassic crinoid “plates” (Cortes et al., 2020) [10] were found in the Meso-Pleistocene site of Gesher Benot Ya’akov (Goren-Inbar et al., 1991) [11].

In other Acheulean sites in northern France and England, spherical fossil sponges with natural perforations have been collected and interpreted as ornamental objects, since some of them show intentional modifications. This is the case of the molds of Coscinopora globularis from St. Acheul (Bednarik 2005; Rigaud et al., 2009) [12,13], considered the oldest documented example of the use of this material for the elaboration of beads and whose symbolic use is still under analysis.

The review, carried out in search of fossil evidence in Iberia (Cortes et al., 2020) [10], where 82 archaeological sites were spatially and temporally framed, led to the conclusion that the practice of fossil collecting appeared to have become widespread in Europe from the Upper Paleolithic period onwards. But it seems that Neanderthal sites also contain evidence of this practice. The aesthetic concerns of these groups can be seen in objects such as the plate engraved on a mammoth molar and the spherical fossil nummulites from Tata (Hungary) (Marshack, 1989) [14] as well as other objects made from teeth, claws and shells.

They have left evidence of their curiosity for exotic objects in several sites where marine fossils were found. Some, as we have already noted, were interpreted as necklace beads or ornaments, such as the fossil echinoderm from Bedford in Great Britain (Otte, 1996) [15]. Others were interpreted as containers for pigments, such as the Pecten maximus (Linnaeus, 1758) [16] shell from Cueva Antón (both the shell and the pigments come from several kilometers away from the site), the shell of the mollusk Spondylus gaederopus Linnaeus, 1758 found in the Cueva de los Aviones, used as a container for a mixture of pigments, or the perforated shells from this same cave (Acanthocardia tuberculate (Linnaeus, 1758) and Glycymeris nummaria (Linnaeus, 1758) (=G. insubrica (Brocchi, 1814). Other collected objects include several perforated incisors and canines and two fossil shells of Bayania lactea, as well as a fossil belemnite from Level X of the Grotte du Renne (Gourhan, 1961) [16], a Rynchonella that had been modified with striations, and the perforated shell of Nucella lapilus (Linnaeus, 1758) recovered in the Mousterian levels of the Arlanpe cave (Vizcaya) (Gutiérrez, 2013) [17]. In several Italian and Greek sites, Neanderthals used Callista chione (Linnaeus, 1758) and Glycymeris sp. shells for the manufacture of tools during the Middle Paleolithic (Douka and Spinapolice 2012, Stiner 1993, Jaubert, et al., 2022) [18,19,20], as in Merry-sur-Yonne (France) where a scraper was found on a fossil, specifically, the internal flint casting of a Cretaceous Micraster, found in a Chatelperronian level. Researchers claim that the piece was brought from a site at least 30 km away (Poplin, 1988) [21].

There are other Acheulean sites, such as West Tofts and Swanscombe, both in Great Britain, or Bleville andr Beauquesne, in France, among others, with pieces such as bifaces with fossils well centered on the tools (Burguete 2019) [22]. These pieces suggest that the carver wished to preserve and leave the fossil in a prominent place in the pieces.

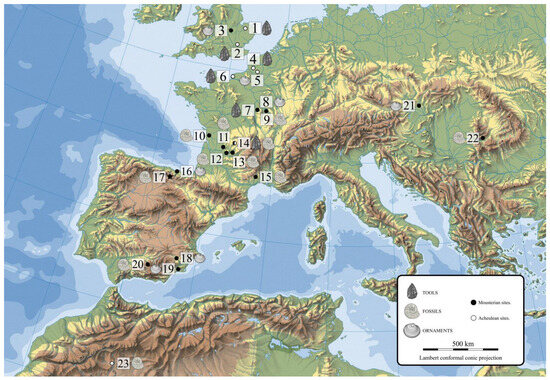

That Neanderthal groups made use of elements such as bone, claws, shells or pigments for activities beyond the food sphere—sometimes as containers for pigments, as personal ornaments, musical instruments, etc.—has been demonstrated. But how do we interpret objects that go beyond the functional sphere? That is, fossils that do not bear traces of human manipulation, that appear to not have been used as personal ornaments or as tools, and of which evidence is found in pre-Neanderthal or late Achelian and Neanderthal settlements (Figure 1). The oldest known fossil was recovered at Level 61 of the Combe Grenal (Figure 1) level associated with the evolved Acheulean industry. It was a Rhynchonellidae (Teraebratulina). The second fossil from this cave, classified as Mousterian Quina, comes from Level 24 and was a Zeillerinae (Lorblanchet and Bahn, 2017) [23]. It is imperative to mention the discovery in Erfoud (Morocco) (Figure 1) of a siliceous filling of a mold of a fossil, specifically, a cephalopod mollusk of the species Orthoceras sp. In addition to its age, which researchers place in the late Achelian, and the fact that it appears associated with a windbreak or a habitation structure, its size and shape are remarkable, as it resembles a human penis (Bednarik, 2002) [24].

Figure 1.

Map of the archaeological sites mentioned in the text. 1, West Tofts; 2, Swanscomb; 3, Bedford; 4, Beaunesque; 5, Saint Acheul; 6, Bléville; 7, Roche au Loup; 8, Grotta du Renne; 9, Grotte de L’Hyene; 10, Saint Cesaire; 11, La Ferrasie; 12, Combe Grenal; 13, Pech de L’Aze I; 14, Chez-Pourré-Chez-Comte; 15, Lunel-Viel; 16, Arlanpe; 17, Prado Vargas; 18, Cueva Antón; 19, Cueva de los Aviones; 20, Cueva de la Carihuela; 21, Tata; 22, Bordul Mare Cave; 23, Erfoud.

At the French site of Chez-Pourre-Chez-Comte (Figure 1), researchers recovered a fossil filler of a bivalve (Glyptoactis (Baluchicardia) sp.) and a small flint flake containing another fossil embedded in it. The Chez-Pourre-Chez-Comte industry next to which the fossil was found is a Charentian Mousterian. Researchers suggest that it came from dozens of kilometers away (L’Homme and Freneix, 1993) [25].

At Level 15 of the Grotte de l’Hyenne at Arcy-sur-Cure (Figure 1) (Leroi-Gourham, 1961) [16], archaeologists recovered two fossils corresponding to a globular coral and a spiral gastropod, which, according to Leroi-Gourhan, were collected in the immediate vicinity.

In level 4 of Pech de l’Azé I (Figure 1), Soressi collected a brachiopod of the family Terebratulidae, which is said to have been transported from a site more than 30 km away (Soressi and d’Errico, 2007) [3].

At Ferrassie (Figure 1), there is a burial with a bone with parallel incisions and a limestone slab with colored remains, a rock with cupules whose meaning we do not know, but which alerts us to many activities whose interpretation escapes us. Finally, it should be noted that a fossil bivalve (Pecten sp.) was recovered (Lorblanchet and Bahn, 2017) [25], an element that is relevant to this work. Other French sites, such as La Plane, have given us a flint plate that preserves a fossil bivalve (Pecten sp.) on one of its sides, while on the other, it presents less well-preserved remains of another specimen. The piece was apparently lashed with the intention of leaving the fossil in a central position (Lorblanchet and Bahn, 2017) [25]. At Lunel-Viel (Figure 1), several fossils and seal teeth collected from very distant areas were recovered (Hayden, 1993) [26].

Two other fossils were documented in Grotte du Renne (France) (Figure 1) by Leroi-Gourhan (1961) [16]. One was a fossil bivalve shell that apparently has a perimeter groove for fastening for possible use as a pendant or earring, and the other was a perfectly circular Crinoid with a natural orifice in its center. On the other hand, at the Chatelperronian level of Saint-Césaire, and associated with a Neanderthal burial, several tubular shells of the marine mollusk of the family Dentalidae were found.

At the Romanian site Grotte Bordul Mare in Ohaba Ponor (Figure 1), they recovered a bivalve at a Mousterian level, which was also interpreted as movable art and which suggests, according to Marin and Nitu, (2010) [27] a female vulva, a motif represented in Upper Paleolithic parietal art in Western Europe.

In the Carihuela cave (Figure 1), in the southern Iberian Peninsula, Dentalidae sp. shells and a fragment of marine mollusk were documented in the Mousterian levels (Vega Toscano, 1988) [28].

Through this journey, we see that Neanderthals, and other species before them (Cortés-Sanchez et al., 2020) [10], have collected objects whose natural beauty or perceived aesthetics attracted their attention. Some of their sites contain crystals, fossils and exotic minerals from distant origins that go beyond the dietary, technological or functional spheres. The examples we have presented show one or two such items. The case of Level 4 of Prado Vargas is interesting because it is the only place known so far where we can speak of a collection of 15 specimens collected from the environment and stored at this level by its inhabitants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Taxonomic classification of the identified fossil species, their references and the biometric data of each specimen (Øu-p: umbo-paleal diameter; Øa-p: antero-posterior diameter; H max: maximum measured height; A max: maximum measured diameter or width; H oral-aboral: oral-aboral height).

2. Prado Vargas Site

2.1. Geoarchaeological Background

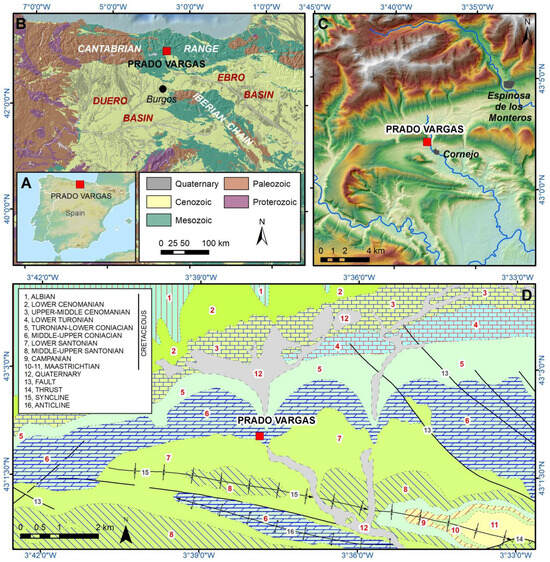

The Prado Vargas cave is located in the Merindad de Sotoscueva town of Cornejo, in the province of Burgos (Northern Spain). The cave belongs to the sixth level of the Ojo Guareña endokarstic system (Navazo et al., 2021) [5] located in the western margin of the Trema Valley, which is a tributary of the Upper Ebro basin. Prado Vargas cave was formed by an old spring in the Middle-Upper Coniacian limestones and dolostones (Figure 2), which dip 1015° to the south, forming a structural cuesta in the northern limb of the La Mesa-Pereda Syncline (Ramírez del Pozo et al., 1978) [29]. The cave is a 90 m long subhorizontal passage situated +23 m above the Trema channel, suggesting that the cavity could have been formed in the Middle Miocene, according to the incision evolution reconstructed for the Upper Ebro River (Benito-Calvo et al., 2022; Karampaglildis et al., 2022) [30,31]. The cave contains a 9.6 m-thick stratigraphic sequence, consisting of autochthonous sediments made chiefly of clays, clayey sands, gravels and limestone blocks, which were divided into nine lithostratigraphic units. The Mousterian Level N4 is contained in the lithostratigraphic unit PV4, which is situated around 50 cm below the current cave floor and is integrated by red clays with limestone blocks and local subangular limestone pebbles formed during the MIS3 (Navazo et al., 2021) [5].

Figure 2.

Geological and geographical situation of Prado Vargas site. (A) Geographical situation in the Iberian Peninsula. (B) Main geological units. (C) Topographical location. (D) Geological units and structures around Prado Vargas cave (after Ramírez del Pozo et al., 1978 [29]). Legend: 1, Sandstones and limonite (Early Cretaceous, Albian), 2, Carbonated sandstones and sandy limestones (Late Cretaceous, Lower Cenomanian), 3, Marls and clayey limestones (Late Cretaceous, Upper-Middle Cenomanian), 4, Limestones and clayey limestones (Late Cretaceous, Lower Turonian), 5, Marls and clayey limestones (Late Cretaceous, Turonian-Lower Coniacian), 6, Limestones and dolostones (Late Cretaceous, Middle-Upper Coniacian), 7, Limestones and clayey limestones (Late Cretaceous, Lower Santonian), 8, Limestones and marls (Late Cretaceous, Middle-Upper Santonian), 9, Sandy Limestones (Late Cretaceous, Campanian), 10, Green claystone (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian), 11, Limestones and sandy limestones (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian), 12, Gravels, sands and clays (Quaternary), 13, Faults, 14, Thrust, 15, Syncline, 16, Anticline.

2.2. N4 Level Archeological Assemblage

After two small excavation campaigns in 1986 and 2006, and given the scientific interest in its sequence, chronology and archaeological record, the cave has been excavated uninterruptedly since 2016. At that date, our interdisciplinary team started the excavation of a full extension of Level N4, which was dated around 39.8–54.6 ka BP (MIS3), combining OSL and 14C (Navazo et al., 2021) [5]. Pollen studies have identified open herbaceous Juniperus and Betula around the cave, suggesting cold climatic conditions with a degree of humidity.

The studies conducted so far suggest that this level was a stable camp of a group of Neanderthals. The presence of children in the group is attested by the milk tooth recovered in this level (Navazo et al., 2021) [5]. Conditions were slightly colder than today, but not significantly, and the group used pine as fuel to light several fireplaces, which structured their living space. Their diet was based on deer (Cervus elaphus) and goats (Capra pyrenaica and Rupicapra pyrenaica) and, to a lesser extent, on Equus ferus, Sus scrofa, Bos/Bison, Oryctolagus sp. or Meles meles, all of which were transported to the cave, where the carcasses were intensively processed to take advantage of everything from the meat to the marrow (de la Fuente Juez et al., 2022) [32]. In fact, their use did not end there, as certain bone fragments became part of the technological sphere, being used as retouches (Alonso-García et al., 2020) [33].

The inhabitants of Prado Vargas employed a recycling economy. This was performed namely by transforming bone fragments from food waste into bone retouchers and limb bones into bone tools, selected according to their size and freshness (dry or green bones) (Alonso-García et al., 2020 and Navazo et al., 2021) [5,33]. In addition, they used the angular blocks falling from the roof as chairs or tables along with sandstone pebbles that came up from the Trema River located 20 m below the cave. From the evidence, we can imagine some of their daily activities, but others escape us. We know that they carved their tools with flint from the surrounding area and that they recycled their tools. Cretaceous flint cores that are exhausted until it is impossible to exploit them further were sometimes converted into tools, retouching one of their edges, or were used without retouching (Navazo, et al., 2022) [34]. The flakes that are the object of exploitation are mostly used with blunt edges, and those that are retouched usually have blades with simple or semi-abrupt angle retouches in the form of endscrapers and denticulates. Perforators or becs with dihedral angles appear insistently in the assemblage. Other less-represented raw materials are quartzite and shale, whose sources of supply we are still looking for. The study of traces of use of the tool edges reveals activities such as butchery and woodworking (Santamaría et al., 2021) [35]. The large number of bone retouchers that have appeared at this level and whose meaning we are trying to understand (Alonso-García et al., 2020) [33] is striking. There are also sandstone nodules that could have been used to remove the hair from animal hides or to treat or clean them in some other way.

3. Fossil Collection

So far, the excavation of the Mousterian level N4 in the Prado Vargas cave site has provided a Cretaceous fossil collection, composed of fifteen specimens (Figure 3); the number and the characteristics of the specimens are unprecedented in Mousterian sites. The most common are the species of the genus Tylostoma Sharpe, 1849, but others have also appeared, such as a Granocardium Gabb, 1869, a bivalve of the genus Pholadomya Sowerby, 1823, and a gastropod of the family Pleuromariidae.

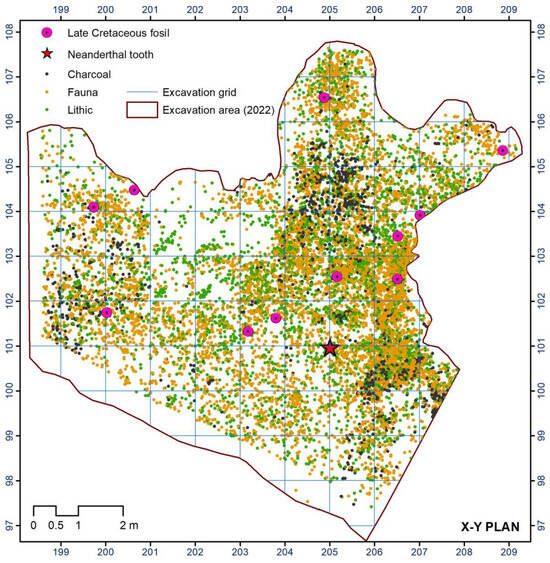

Figure 3.

Distribution of archaeological record from Level 4.

The group of identified species offers a dating that is consistent with the Cretaceous period and more specifically with the Upper Cretaceous. The area where Prado Vargas is located represents levels of sandstones, sands, limestones, or marls from the Cenomanian to the Coniacian, but one can find them up to the Santonian (Upper Cretaceous) and the Aptian-Albian from the end of the Lower Cretaceous (Vera, 2004) [36] (Figure 2).

Specifically, 15 fossils were identified (Table 1): 13 mollusks (seven gastropods and six bivalves), one echinoderm and an unidentifiable fragment (PV18 H30N 566). The mollusks are classified into two classes: Gastropoda and Bivalvia. The bivalves are represented by four families: Gryphaeidae Vialov, 1936, Family Pectinidae Wilkes, 1810, Family Cardiidae Lamarck, 1809, Pholadomyidae King, 1844. Of the five bivalve toaxons, three were classified at the specific level (Chlamys aff. guerangueri (Farge in Couffon, 1936), Granocardium productum (Sowerby, 1832) and Pholadomya gigantea (Sowerby, 1836)); one at the genus level (cf. Ilymatogyra sp.) and one at the family level (cf. Pectinidae sp.). Two families are represented in the class Gastropoda: Pleurotomariidae Swainson, 1840 and Tylostomatidae Stoliczka, 1868. The first with one species identified at the genus level: Pleurotomaria sp. and the second with two taxa identified at a specific level and another at a generic level (Tylostoma cossoni Thomas and Peron, 1889, Tylostoma ovatum Sharpe, 1849 and Tylostoma sp.). The representative of the phylum Echinodermata Klein, 1734, belongs to the Class Echinoidea Leske, 1778 and the family Diplopodiidae Smith and Wright, 1993: the species Tetragramma variolare (Brongniart, 1822).

The taxonomic classification is as follows:

3.1. Filum Mollusca Linnaeus, 1758

3.1.1. Class Bivalvia Linnaeus, 1758

- Family Gryphaeidae Vialov, 1936

- ⁻

- PV22 8857, a fragment of the umbo of a specimen of cf. Ilymatogyra sp. A fragment of the beak of a left valva preserves the shell (beak-pallial diameter of the fragment: 14.14 mm; anteroposterior diameter of the fragment: 11.65 mm). Beak opisthogyric, very rounded and slightly involute, very convex and thick, with a rounded appearance. The hinge is almost circular in shape. Internally, on the dorsal and anterior margin, part of the chomata is visible. Dorsally there is no sculpture.

The genus Ilymatogyra Stenzel, 1971, had a wide distribution during the Cretaceous (Cox et al., 1969; Abad et al., 2021) [37,38]. The fragment that was found mainly corresponds only to the beak, which is not very prominent and is thick and without sculpture. These characteristics suggest that it belongs to the genus Ilymatogyra, a representative of the subfamily Exogyrinae that is characteristic of the Cenomanian (Cox et al., 1969; Berrocal-Casero et al., 2013; Moratilla-García et al., 2015) [37,39,40].

- Family Pectinidae Wilkes, 1810

- ⁻

- PV20 4998 Chlamys aff. guerangueri (Farge in Couffon, 1936), a fragment of the inner ventral margin. The disposition, regularity and width of the equidistant radial ribs and the regularly curved ventral margin correspond to an individual of the genus Chlamys and the width of the ribs and their distribution are reminiscent of the species Ch. guerangueri.

Ch. guerangeri is common in the Upper Cenomanian of Portugal (Callapez, 1992; Berrocal-Casero, 2013) [39,41] and is reported from the Upper Cenomanian-Lower Turonian of Guadalajara (Spain) (Berrocal-Casero, 2013) [39].

- ⁻

- PV16 F28 and G27 cf. Pectinidae sp. correspond to two fragments, both internal casts which may correspond to species of this family.

- Family Cardiidae Lamarck, 1809

- ⁻

- PV22 9047 Granocardium productum (Sowerby, 1832). A cast of the left valva of G. productum which retains part of the shell on the anterior margin (Figure 4).

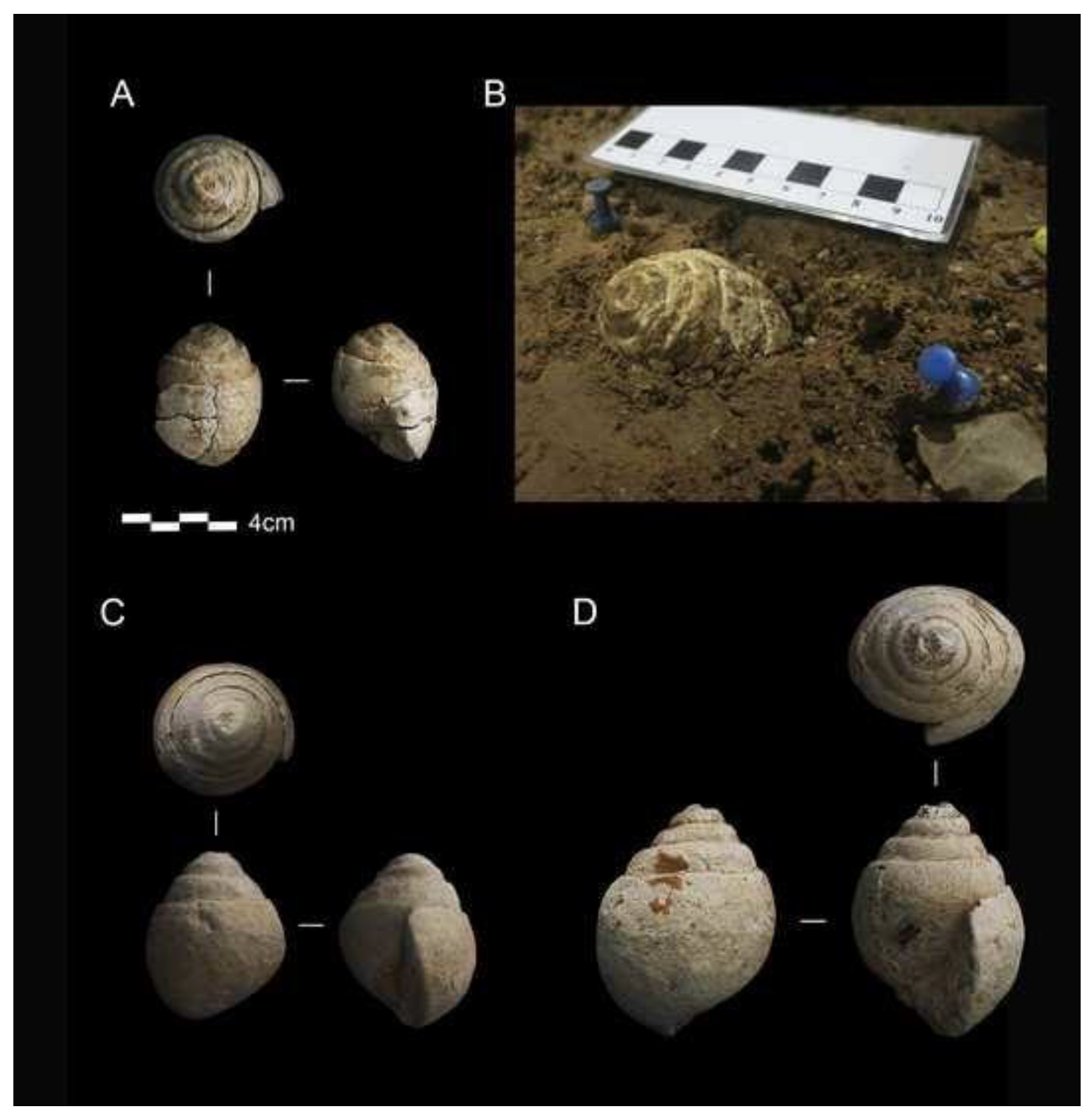

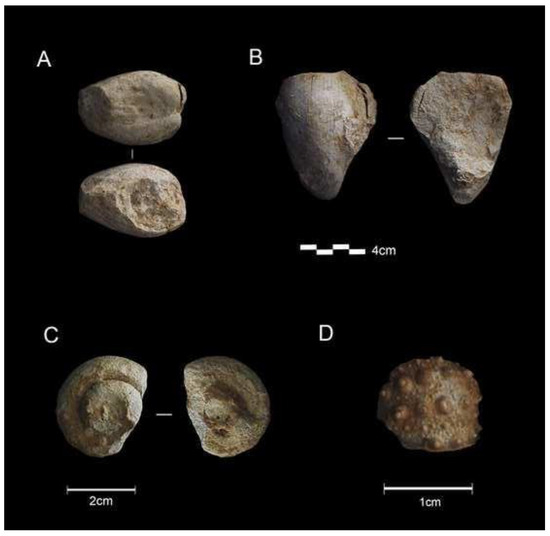

Figure 4. Marine fossils from Level 4. (A) Pholadomya gigantea (Sowerby, 1836) (PV18 H29 159); (B) Granocardium productum (Sowerby, 1832) (PV22 9047); (C) Pleurotomaria sp. (PV20 F27); (D) Tetragramma variolare (Brongniart, 1822) (PV19 G27).

Figure 4. Marine fossils from Level 4. (A) Pholadomya gigantea (Sowerby, 1836) (PV18 H29 159); (B) Granocardium productum (Sowerby, 1832) (PV22 9047); (C) Pleurotomaria sp. (PV20 F27); (D) Tetragramma variolare (Brongniart, 1822) (PV19 G27).

Shell of medium-to-large size (measured beak-paleal diameter: 80.27 mm; measured anterior-posterior diameter: 55.60 mm), quadrangular-ovate. The posterior margin is broken but appears to be slightly unequal and equivalent. The beak is broken but appears prominent and apparently orthogyric. The dorsal margin is short and steeply sloping is formed which is almost non-existent, occupied almost entirely by lunule. Lunule broad oval which occupies 1/3 of the length of the shell. The ventral margin is arched, although in this case, it is broken in such a way that it forms a straight line. The anterior margin is very sloping, almost straight, and forms a wide curve when joined to the ventral margin. The hind margin is broken along its entire length. The external sculpture is based on radial ribs which leave a fine, parallel striation along the dorso-ventral length of the shell in the internal mold. In the shell preserved on the anterior margin, it can be seen that these fine striations correspond to thicker, tuberculate ribs running along the entire length of the radial ribs. Internally, the hinge is rectilinear, and a broad, strongly triangular central cardinal tooth appears to be visible. No other internal features are observed.

This species is cited from the Upper Cretaceous, being common in the Upper Cenomanian of Portugal (Soares, 1966; Callapez, 1992; Berrocal-Casero et al., 2013) [39,41,42]. It is cited in Spain by Calzada and Carrasco (2010) [43] for the Campanian and for the Upper Cenomanian-Lower Turonian by Berrocal-Casero et al., (2013) [39].

- Family Pholadomyidae King, 1844

- ⁻

- PV18 H29 159 Pholadomya gigantea (Sowerby, 1836). A single articulated specimen of P. gigantea (Sowerby, 1836) is available, which preserves the shell, although it is very eroded so that it is not possible to observe the internal characteristics and not all the external characteristics (Figure 4).

Shell of medium size (beak-paleal diameter measured: 64.37 mm; antero-posterior diameter measured: 41.36 mm), elliptical, elongate antero-posteriorly and strongly inequilateral. Valvae open posteriorly. Beak rounded and bulging, prosogyrate and arranged anteriorly. Lunule broad and oval, wider towards the posterior side of the shell. Dorsal margin straight which curves gently towards anterior end, ventral margin curved. Anterior and posterior margins arched, the posterior being wider than the anterior. Sculpture based on oblique radial ribs which start from the beak towards the posterior margin.

Pholadomya Sowerby, 1823 is a cosmopolitan genus which is represented from the Upper Triassic to the present day (Cox et al., 1969) [37]. The species P. gigantea is a geographically widespread Upper Cretaceous bivalve mollusc (Lazo, 2007) [44].

3.1.2. Class Gastropoda Cuvier, 1797

- Family Pleurotomariidae Swainson, 1840

- ⁻

- PV20 F27 Pleurotomaria sp. An internal cast of a representative of the genus Pleurotomaria Fischer, 1885 is available.

Disk-shaped-trochiform shell, strongly compressed in umbilical view. It is an internal mold in which only the two most adult turns of the spire have been preserved. The shell is about twice as high as it is wide (maximum measured height: 11.68 mm, maximum measured diameter: 30.35 mm). The last two turns are very wide and flattened, somewhat convex in profile and oblique at an angle of about 45° to the axial axis of the shell. They have a short sutural ramp perpendicular to the axial axis. The turns form an angle close to 90º at the base. Ornamentation unknown. In umbilical view, the shell is flattened and in its centre, there is a wide, rounded, deep umbilicus, centered adaxially. The opening is subtriangular-rounded. Labrum broken. No details are observed.

Representatives of the family Pleurotomariidae are mostly medium-to-large-sized, trochomorphic and have a gap that generates a selenizone which is not observed in this case. They are distributed from the Triassic to the present day. The genus Pleurotomaria is distributed from the Lower Jurassic to the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian) (Brookes Knight et al., 1960) [45].

- Family Tylostomatidae Stoliczka, 1868

- ⁻

- PV22 8767 Tylostoma cossoni Thomas and Peron, 1889

Siphonostomatus shell, large (maximum measured height: 76.49 mm, maximum measured diameter: 63.26 mm) with more than five turns of the spire, with the first turns of teleoconch and the protoconch broken. The shell is turriculate-scalariform, 1.5 times as high as it is wide, with a very large, globose last turn and somewhat staggered spiral turn. The ornamentation is smooth, part of the shell is very eroded, although it maintains the shape of the turns, with some deformation due to lateral compression. The lobes are slightly convex, low and 4.5 times wider than they are high. The outline of the turns is oblique at about 60° to the suture (or 30° to the axial axis of the shell). A small sutural ramp is observed. The turns are completely smooth. Growth lines are not visible except for a line on the last turn. The suture is grooved, very well marked, not sinuous. The spire is half as high as the last turn, and slightly wider than high (Figure 5D).

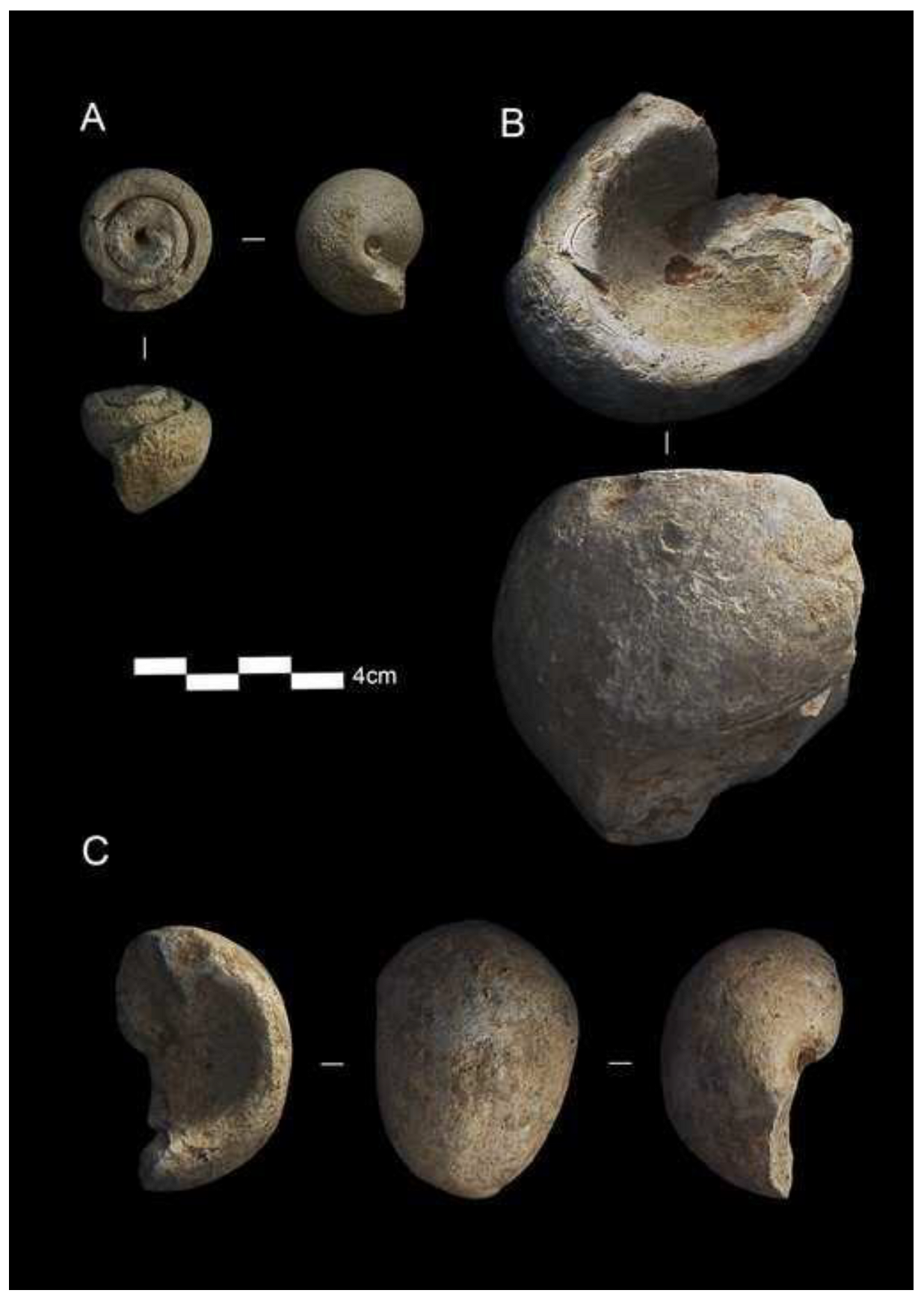

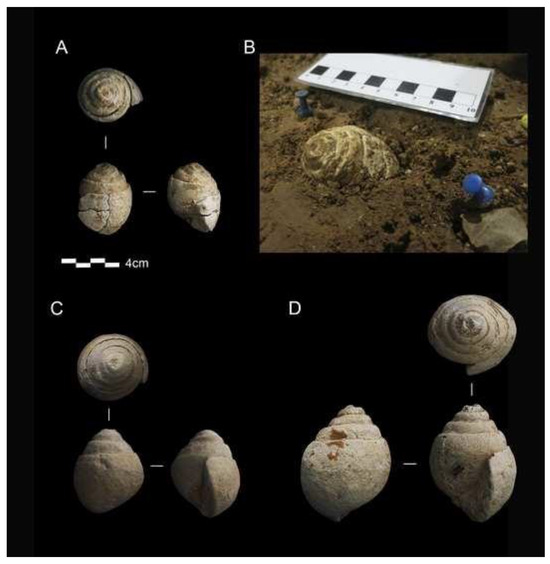

Figure 5.

Marine fossils from Level 4. (A) Tylostoma ovatum Sharpe, 1849. (PV17 G28 112); (B) Tylostoma ovatum Sharpe, 1849 (PV17 G28 112) in situ; (C) Tylostoma ovatum Sharpe, 1849 (PV21 7804); (D) Tylostoma cossoni Thomas and Peron, 1889 (PV22 8767).

The last turn of the teleoconcha is very well preserved, convex in profile, and twice as high as the spiral, which is as high as it is wide. Completely smooth. The area of greatest convexity of the shell coincides with the middle of the height of the last turn. The opening is elongated-oval, narrow. It has an elongated, oblique, teardrop-shaped umbilicus, which extends axially. The external labellum is broken, although there is a well-preserved, slightly opisthotic growth line near the labellum describing a small, adapically stromboid sinus.

The specimen under study is a Tylostoma (Family Tylostomidae Stoliczka, 1868) with some similarities to Tylostoma torrubiae Sharpe, 1849, the latter species differs from the specimen under study by presenting the turns and the spire higher and narrower and in general the shell is less globose. In addition, the turns have a level profile, while the specimens studied here have turns with a more stepped profile. The umbilicus is much larger.

- ⁻

- PV17 G28 112 and PV21 7804 Tylostoma ovatum Sharpe, 1849

Syphonostomatus shell, medium to large (maximum measured height: 47.91 mm, maximum measured diameter: 35.28 mm; maximum measured height: 60.27 mm, maximum measured diameter: 48.67 mm, respectively) of more than five turns of the spire, with the first turns of teleoconch and protoconch broken. The shell is turriculate, almost as high as wide, with a very large, globose last turn and spiral turns inclined at an angle of about 30° to the shell axially, slightly convex, and elevated. The turns are irregular. The suture is somewhat sinuous and grooved. The ornamentation is smooth. A small sutural ramp is observed in the smallest specimen. The laps are completely smooth. The growth lines are not visible. The suture is grooved, although not very marked and not sinuous (Figure 5A–C).

The last turn of the teleoconch is very well preserved, convex in profile, and almost as high as the spire, which is wider than it is high. Completely smooth. The area of greatest convexity of the shell coincides with half the height of the last turn. The opening is elongated-oval, narrow. There is an elongated, oblique, teardrop-shaped umbilicus, which extends axially and is covered by a columellar callus. The external labellum is broken.

They differ from Tylostoma cossoni in being very rounded, globular and with a much lower spire. The turns are irregular, and the suture is somewhat sinuous, also grooved. The specimens studied broadly agree with the holotype of Tylostoma ovatum figured by Sharpe (1849). Tylostoma globosum Sharpe, 1849, from the Turonian of Coimbra (Portugal) (see Sharpe, 1849; Callapez and Ferreira Soares, 1991) [46,47] differs from T. ovatum in having a more inflated shell and a rather low spire.

PV18 H30 196; PV21 7515 correspond to two specimens of Tylostoma sp. of which only the internal mould of the last round is preserved (Figure 5).

PV20 5239 a cast of Tylostoma sp., (figure also broken, is an internal cast of the last lap and part of the penultimate lap, although very eroded (Figure 6).

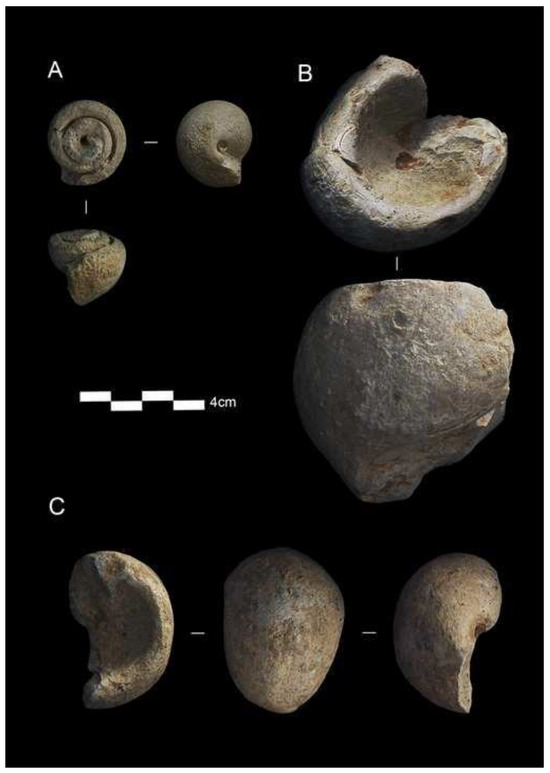

Figure 6.

Marine fossils from Level 4. (A) Tylostoma sp. (PV20 5239); (B) Tylostoma sp. (PV18 H30 196); (C) Tylostoma sp. (PV21 7515).

In the specimens referenced as PV18 H30 196 and PV21 7515, the last turn of the spire is large (maximum measured height of last turn: 71.21 mm, maximum measured width of last turn: 66.89 mm; maximum measured height of last turn: 48.70 mm, maximum measured width of last turn: 51.08 mm, respectively), thick and globose. The opening is an elongated oval. An umbilicus is visible, filled and hidden by a columellar callus. The surface of the mold is smooth, reflecting no ornamentation. No other features are observed.

Specimen PV20 5239 is a smaller internal mold (maximum measured height: 24.43 mm, maximum measured width: 27.88 mm), it is eroded and broken. The opening is elongated-oval. An umbilicus is visible, which is not covered by the detached columellar callus. The surface of the mold is smooth, reflecting no ornamentation. No other features are visible.

Tylostoma Sharpe, 1849 is a genus defined for the Cenomanian of Portugal by Sharpe (1849) [46]. Species of the genus Tylostoma are Cretaceous stromboid gastropods (Superfamily Stromboidea Rafinesque, 1815) of the family Tylostomatidae Stoliczka, 1868 (Bouchet and Rocroi., 2005) [48]. They have an oval or globose shell, thick and almost smooth, with a moderately elevated spire: an oval opening that narrows towards the apex of the shell. The edge of the outer lip is generally thickened which may be repeated at regular intervals and is accompanied by a temporary upward elongation of the aperture; inner lip calloused and extended over the body to almost conceal the columella (Sharpe, 1849) [46].

3.2. Phylum Echinodermata Klein, 1734

Class Echinoidea Leske, 1778

- Family Diplopodiidae Smith and Wright, 1993

- ⁻

- PV19 G27 corresponds to the echinoderm species Tetragramma variolare (Brongniart, 1822) (Figure 4).

Only one fragment is available, showing two strips of ambulacral pores separated by two strips of primary ambulacral tubercles and between them a strip of secondary tubercles. The arrangement of the tubercles and the size of the fragment (oral-aboral height of the fragment: 12.86 mm) correspond to that of specimens of the species T. variolare.

The genus Tetragramma Agassiz, 1840 occurs in the fossil record between the Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) and Upper Cretaceous (Upper Cenomanian), in southern Europe, North Africa, Asia, India and North America. T. variolare is very common in the Cenomanian of the Thetis, from Portugal to Egypt and Jordan (Fell and Pawson, 1966; Soares and Marques, 1973; Berndt, 2003; Berrocal-Casero et al., 2013; Moratilla-García et al., 2015) [39,40,49,50,51].

4. Discussion

The accumulation of fossils in Level 4 of Prado Vargas is exceptional compared to what was found in the sites reviewed above. These fossils are mainly Upper Cretaceous fauna and in many cases are characteristic of Cenomanian formations. Upper Cretaceous formations around Prado Vargas cave are common (Figure 1, Ramírez del Pozo et al., 1978) [29]. The cave is located in Coniacian limestones. Above these limestones, no Cretaceous formations are currently preserved. The structural cuesta formed by this limestone and situated above the cave would have been exhumed long much before the formation of Level N4, perhaps during the Pliocene and the Lower-Middle Pleistocene, according to the denudation evolution proposed for the area and the Upper Ebro River (Karampaglisids et al., 2022, Benito-Calvo et al., 2022) [30,31]. This would preclude the provenance of the N4 fossils from the Upper Cretaceous geological formations situated above the cave. Moreover, in many cases, N4 fossils are characteristic or common to Cenomanian formations, which are older than the Coniacian limestones, and geographically are only located to the north of the Prado Vargas cave (Figure 2). Although drainage networks, such as the Trema River and its tributaries, could have transported these Cretaceous fossils near the Prado Vargas cave, the sedimentological characteristics of the PV4 lithoestratigraphic unit (Navazo et al., 2021) [5], composed of clays, clay sands and limestone clasts, indicate that these are mainly sediments autochthonous to the cave formed in vadose conditions by current and stagnant waters. Additionally, during the formation of PV4 (39.8–54.6 ka BP, MIS3), the Trema River would be at a lower position than Prado Vargas Cave, since Upper Ebro terraces lying at relative elevations of +11 m were estimated at 180ka (Benito-Calvo et al., 2022) [30].

Such evidence indicates that the Upper Cretaceous fossils must have been brought by Neanderthals to the cave, just as the rest of the N4 archaeological material. The fossils could have been either collected during the group’s usual foraging activities or were specifically sought out. These fossils can be understood as evidence of an artistic interest or an attraction or curiosity for the forms of nature. They do not have a utilitarian purpose and, therefore, their interpretation is controversial.

Leroi-Gourhan offers two explanations for the presence of fossils in Mousterian sites, which he interprets as evidence of the groups’ interest in the fossils’ unusual forms: they acted as a sort of primary figurative art, or they were used for therapeutic or magical purposes (Leroi-Gourhan, 1964, p. 69) [52]. As always, and especially with regard to the Neanderthals, we find counter-positions such as that of Taborin (1993) [53], who does not concede that these groups had the capacity for symbolic thought. According to this author, it is only after the Aurignacians that the presence of these objects can be “charged with meaning”. Perhaps, like we do today, the people who collected them derived pleasure from the act of looking for them or finding them and keeping them. Or they may have been objects of play or may even have had a magical–religious role during ritual activities (Otte, 1996) [15].

Recent studies on recycled flint pieces from the Revadim open-air site in Israel, with a chronology between 500 and 300 ka (Efrati et al., 2022) [54] indicate that half a million years ago, humans were already collectors by nature and by culture. The study demonstrates that the pieces, with a double patina, were first used for cutting, but when they were re-collected, their blades were modified for a second life, and they were used for scraping. The novelty of this work is not the demonstration of the pieces’ double life, i.e., their recycling, but the explanation of the members of the study, who suggest an emotional impulse to collect objects as a means of preserving the memory of their ancestors and maintaining their connection to time and place. These authors assert that, like us, our early ancestors attached great importance to ancient artifacts, preserving them as objects imbued with memory, links to ancient worlds and important sites in the landscape. Currently, collecting is a common behavior described as too human and complex to be summarized in a simple definition (Pearce, 1994) [55], which includes not only the tangible objects’ value but also intangible aspects associated with an experience, idea or feeling (Ijams, 2018) [56]. It can entail competition over acquiring objects, but also cooperation and object-sharing, and it ranges from hobby activities to compulsive hoarding related to obsessive-compulsive personalities (Nordsletten and Mataix-Cols, 2012) [57]. Formanek (1991) [58] identified five main motivations for current collecting: selfishness, selflessness, preservation and restoration of history as a sense of continuity, marketing and financial investment, and addiction.

In addition to the difficulty in interpreting archaeological objects with no apparent practical use, research on the origin and development of these symbolic behaviors in the archaeological record is conditioned by the complexity observable in current human behaviors. Some practices, such as the use of ornaments and furniture, burials, and parietal artistic expressions, even certain cults (such as bear cults) are gradually being confirmed in Neanderthal groups by examples that include the burial of the old man of La Chapelle (with which we begun this text), the engravings of Gorham (Simón-Vallejo et al., 2018) [59], or the bear bone inside the circle built with stalagmites and stalactites found at Bruniquel (Jaubert et al., 2016) [60]. Not to mention the spectacular mask discovered on the banks of the Loire River, in the French cave of La Roche-Cotard. It is an object made by Neanderthals, on a flint block of about 10 cm with two inserted bones simulating eyes (Marquet and Lorblanchet, 2000, Marquet et al., 2016) [7,8], which has been called a Mousterian protofigurine. With an age of 75 ka, it is undoubtedly a unique object of mobiliary art.

The collected fossils that are neither modified nor used as personal ornaments represent a manifestation whose behavioral identification is hard to trace, but which must be associated with tangible or intangible motivations (Ijams, 2018, Formanek, 1991) [56,58]. They can represent ideas, concepts, experiences, beliefs, or even cultural identities, whether individual (associated with selfishness) or group (associated with cooperation and selflessness). They may have been regarded as valuable objects that could be exchanged for other desired objects with members of the same or another group, representing marketing and financial activities. Or they may simply respond to a collecting urge that may have been as intense as an addiction or as simple as a pleasant hobby or entertainment. Collecting is, after all, a universal instinct that arises in children and can be related to the learning process (Howe et al., 1906) [61].

In the case of Prado Vargas, we know that the fossils were collected from the immediate vicinity. The fragment of this tylostoma was apparently used as a striker, given the marks it presents (Figure 5B), while the rest of the fossils can be interpreted as a result of collecting activities, which are so characteristic and complex in modern humans.

But why? For these prehistoric collectors, these treasures had a special character beyond the object itself. They are added values, whether aesthetic, sentimental, magical or symbolic.

With the collection of fossils recovered in Level 4 of Prado Vargas, the debate is on. It is clear that these fossils have some meaning and symbolize something. Reflecting on how this collection of fossils has reached Prado Vargas, several hypotheses emerge.

- They might have been found intentionally or by chance, but their transport to the cave must have been deliberate, implying an impulse to collect these fossils. In either case, they would represent a special meaning;

- The motivations for collecting fossils are complex and could include group or individual reasons related to identity, such as preserving the memory of their ancestors or attachment to the landscape;

- They might have been collected simply for aesthetic or decorative reasons;

- They might have been used as gifts or for exchanges within the group or with external groups;

- They could have been used to reinforce a group’s cultural identity and social cohesion, both of which are often given special importance in times of stress;

- They might have been collected by children. The collection of objects is characteristic of childhood, and remains of Neanderthal children were found in Prado Vargas. According to specialists, collecting behavior appears in human children between the ages of 3 and 6, when they begin to be aware of themselves and continues until they are 12 years old. At puberty and up to the age of 18, we continue collecting, but from this point on, this infantile eagerness weakens a little, to return with force, they say, after the age of 40. It could be that the youngest members of the group, fascinated by these forms, were the ones who started the collection.

- Accepting the fact that we can trace the symbolic capacities of the Neanderthal groups from materials, such as bones, claws, pigments, shells, etc., and from the uses of the materials as containers, body paint and maybe walls, musical instruments, and even sculptures, we must now document and interpret the exotic objects, that is, those that have been introduced in their places of habitation and that do not present any modifications or functionality whatsoever. Thanks to the collection recovered in Level 4 of Prado Vargas and opening the debate on the contacts with the HAM and possible acculturation, we have to say that in these chronologies in this area, there is no evidence of the arrival or presence of Homo sapiens. Therefore, we are looking at a fully Neanderthal behavior, so it is clear that collecting arose before the arrival of the Sapiens and the contact between them and the Neanderthals.

Be that as it may, it is clear that the Neanderthal groups that inhabited the Prado Vargas cave gathered and collected fossils, just as we look for fossils, even of these human species, to study them and finally “collect” them in museums. This seems to become an infinite spiral through which, at some point, we will be part of what we collect.

5. Conclusions

In the N4 Mousterian level of the Prado Vargas cave site, 15 Upper Cretaceous marine fossils have been recovered, which were brought to the cave by Neanderthal groups, and only one of them shows traces of having been used as a hammer. The rest do not present modifications that indicate their practical use as tools; so, they could be interpreted as the product of collection activities. This would indicate that Neanderthals had psychological and behavioral characteristics similar to those of our species, for which collecting is a common and complex practice motivated by numerous tangible and intangible causes, including competition, cooperation, symbolism, selfishness, selflessness, a sense of continuity, marketing, or addiction, among others. The Neanderthals’ motivation for bringing this set of fossils to the Prado Vargas cave might have been complex, and we have no valid hypothesis that can explain it. However, we should not forget the presence of children in the cave, for the collecting instinct characteristic of children could have had a relevant role in the set’s existence. In any case, the Upper Cretaceous fossil collection of the Prado Vargas cave site suggests that collecting, and the abstract thought that it entails, characterized Neanderthals before the arrival of Homo sapiens.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, M.N.R. and M.C.L.-F.; Investigation, M.N.R., A.B.-C., R.A.A. and P.C.C.; Resources, R.A.A. and H.d.l.F.J.; Data curation, M.S.D.; Writing—original draft, A.B.-C.; Writing—review & editing, M.N.R.; Visualization, P.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Rafael Sánchez and Nicolas Gallego for their help with the identification of the fossils and the excavation team that has made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Rodrigo Alonso Alcalde was employed by Museo de la Evolución Humana. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Tappen, N.C. The Dentition of the “Old Man” of La Chapelle-aux-Saints and Inferences Concerning Neanderthal Behavior. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1985, 67, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendu, W.; Beauval, C.; Crevecoeurd, I.; Bayled, P.; Balzeaumi, A.; Bismutobf, T.; Bourguignong, L.; Delfourd, G.; Faivre, J.P.; Lacrampe-Cuyaubère, F.; et al. Evidence Supporting an Intentional Neandertal Burial at La Chapelle-aux-Saints (Corrèze, France). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soressi, M.; D’Errico, F. Pigments, Gravures, parures: Les Comportements symboliques controversés des néandertaliens. In Les Néandertaliens: Biologie et Cultures; Éditions du CTHS: Paris, France, 2007; (Documents préhistoriques; 23); pp. 297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Mcbrearty, S.; Brooks, A.S. The revolution that wasn’t: A new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior. J. Hum. Evol. 2000, 39, 453–563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Navazo, M.; Benito-Calvo, A.; Alonso-Alcalde, R.; Alonso, P.; de la Fuente, H.; Santamaría, M.; Santamaría, C.; Álvarez-Vena, A.; Arnold, L.-J.; Iriarte, M.J.; et al. Late Neanderthal Subsistence Strategies and Cultural Traditions in the Northern Iberian Peninsula: Insights from Prado Vargas, Burgos, Spain. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2021, 254, 106795. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarik, R.G. The “Australopithecine” Cobble from Makapansgat, South Africa. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 1998, 53, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquet, J.-C.; Lorblanchet, M. Le masque moustérien de La Roche-Cotard, Langeais (Indre-et-Loire). Paleo 2000, 12, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquet, J.-C.; Lorblanchet, M.; Oberlin, C.; Thamo-Bozso, E.; Aubry, T. New Dating of the “java” of La Roche-Cotard (Langeais, Indre-et-Loire, France). PALEO Rev. D’archéologie Préhistorique 2016, 27, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joordens, J.; d’Errico, F.; Wesselingh, F.; Munro, S.; Vos, J.; Wallinga, J.; Ankjærgaard, C.; Reimann, T.; Wijbrans, J.; Kuiper, K.F.; et al. Homo Erectus at Trinil on Java Used Shells for Tool Production and Engraving. Nature 2014, 518, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Sánchez, M.; Simón-Vallejo, M.; Corral, J.C.; Lozano-Francisco, M.C.; Vera-Peláez, J.L.; Jimenez-Espejo, F.J.; García-Alix, A.; de las Heras, C.; Martínez Sanchez, R.; Bretones García, M.D.; et al. Fossils in Iberian Prehistory: A Review of the Palaeozoological Evidence. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 250, 106676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren-Inbar, N.; Lewi, Z.; Kislev, M.E. Bead-like fossils from an Acheulian occupation site, Israel. Rock Art Res. 1991, 8, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarik, R.G. The technology and use of beads in the Pleistocene. In Proceedings of the Archaeology of Gesture Conference, Cork, Ireland, 5–11 September 2005; Available online: http://semioticon.com/virtuals/archaeology/technology.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Rigaud, S.; d’Errico, F.; Vanhaeren, M.; Neumann, C. Critical Reassessment of Putative Acheulean Porosphaera Globularis Beads Solange. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshack, A. Evolution of human capacity: The symbolic evidence. Yearb. Phys. Anthopol. 1989, 32, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, M. Le Paléolithique Inférieur et Moyen en Europe; Revue de Géographie Alpine: Grenoble, France, 1996; Volume 84, p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Leroi-Gourhan, A. Les fouilles d’Arcy-sur-Cure (Yonne). Gall. Préhistoire 1961, 4, 3–16. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/galip_0016-4127_1961_num_4_1_1182 (accessed on 3 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Zugasti, I. Moluscos marinos y terrestres de los niveles paleolíticos de la cueva de Arlanpe (Lemoa, Bizkaia): Consideraciones culturales y paleoambientales. In Kobie. Año 2013 Bizkaiko Arkeologi Indusketak—Excavaciones Arqueologicas en Bizkaia; Rios-Garaizar, J., Garate Maidagan, D., Gómez-Olivencia, A., Eds.; Bizkaiko Foru Aldundia-Diputación Foral de Bizkaia: Bilbao, Spain, 2013; Volume 3, ISSN 0214-7971. [Google Scholar]

- Douka, K.; Spinapolice, E. Neanderthal Shell Tool Production: Evidence from Middle Palaeolithic Italy and Greece. J. World Prehistory 2012, 25, 45–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiner, M.C. Small Animal Exploitation and its Relation to Hunting, Scavenging, and Gathering in the Italian Mousterian. Archeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. Taborin 2008, 4, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaubert, J.; Maureille, B.; Peresani, M. Spiritual and symbolic activities of Neanderthals. In Updating Neanderthals: Understanding Behavioural Complexity in the Late Middle Palaeolithic; Romagnoli, F., Rivals, F., Benazzi, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, F. Aux origines néandertaliennes de l’art. Matière, forme, symétries. Contribution d’une galène et d’un oursin fossile taillé de Merry-sur-Yonne (France). In L’Homme de Néandertal; La Pensée, Université de Liège: Liege, Belgium, 1988; Volume 5, pp. 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Burguete Prieto, C. Evaluación de las Capacidades Cognitivas de Homo Neanderthalensis e Implicaciones en la Transición Paleolítico Medio-Paleotíco Superior en Eurasia. 2019. Available online: https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/56268/1/T41206.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Lorblanchet, M.; Bahn, P.G. The First Artists. In Search of the World’s Oldest Art; Thames & Hudson Limited: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarik, R.G. An Acheulian Palaeoart Manuport from Morocco. Rock Art Res. 2002, 19, 2. [Google Scholar]

- L’homme V et Freneix, S. Un coquillage de bivalve du Maastrichtien paléocène Glyptoacis (Baluchicardia) sp. dans la couche inférieure du gisement moustérien de «Chez--Pourré-ChezComte» (Corrèze). Bull. Société Préhistorique Française 1993, 90, 303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, B. The cultural capacities of Neandertals: A review and re-evaluation. J. Hum. Evol. 1993, 24, 113–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cârciumaru, M.; Nitu, E.-C.; Ţuţuianu-Cârciumaru, M. Témoignages symboliques au Moustérien. In L’art Pléistocène dans le Monde; Tarascon-sur Ariege 2010; Préhistoire, art et sociétés: Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique de l’Ariège. 2012, pp. 1627–1641. Available online: https://blogs.univ-tlse2.fr/palethnologie/wp-content/files/2013/fr-FR/version-longue/articles/SIG03_Carciumaru-etal.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Vega Toscano, L.G.; Hoyos, M.; Ruiz-Bustos, A.; Laville, H. La séquence de la grotte de la Carihuela (Piña, Grenada): Cronostratigraphie et paléolécologie du Pléistocène supérieur au sud de la Péninsule Ibérique. L’Homme Neandertal l’Environnement 1988, 2, 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez del Pozo, J.; del Olmo Zamora, P.; Aguilar Tomás, M.J.; Portero García, J.M.; Olive Davó, A. Mapa Geológico de España e. 1:50.000, 1978, Hoja 84 (19-06), Espinosa de los Monteros. Available online: https://info.igme.es/catalogo/resource.aspx?portal=1&catalog=3&ctt=1&resource=6678&lang=spa&dlang=eng&llt=dropdown&q=puntos%20de%20agua&master=infoigme&shpu=true&shcd=true&shrd=true&shpd=true&shli=true&shuf=true&shto=true&shke=true&shla=true&shgc=true&shdi=true (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Benito-Calvo, A.; Moreno, D.; Fujioka, T.; López, G.L.; Martín-González, F.; Martínez-Fernández, A.; Hernando-Alonso, I.; Karampaglidis, T.; Bermúdez de Castro, J.M.; Gutiérrez, F. Towards the steady state? A long-term river incision deceleration pattern during Pleistocene entrenchment (Upper Ebro River, Northern Spain). Glob. Planet. Chang. 2022, 213, 103813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampaglidis, T.; Benito-Calvo, A.; Ortega-Martínez, A.I.; Martín-Merino, M.Á.; SánchezRomero, L. Landscape evolution and the karst development in the Ojo Guareña multilevel cave system (Merindad de Sotoscueva, Burgos, Spain). J. Maps 2022, 19, 2128907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente Juez, H.; Navazo, M.; Benito-Calvo, A.; Rivals, F.; Amo-Salas, M.; Alonso-García, P. Too good to go? Neanderthal subsistence strategies at Prado Vargas Cave (Burgos, Spain). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2023, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso García, P.; Navazo Ruiz, M.; Blasco López, R. Use and selection of Bone Fragments in the North of the Iberian Peninsula During the Middle Palaeolithic: Bone Retouchers from Level 4 of Prado Vargas (Burgos, Spain). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navazo, M.; Santamaría, C.; Santamaría, M. Using Cores as Tools: Use-wear Analysis of Neanderthal Recycling Processes in Level 4 at Prado Vargas (Cornejo, Merindad de Sotoscueva, Burgos, Spain). Lithic Technol. 2022, 48, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, C.; Navazo, M.; Benito-Calvo, A. Functional Analysis of Middle Paleolithic Flint Tools through Experimental Use Wear Analysis: The Case of Prado Vargas (Cornejo) and Fuente Mudarra (Atapuerca), Northern Spain. Munibe 2021, 72, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, J.A. (Ed.) “Geología de España”. Sociedad Geológica de España; Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Madrid, Spain, 2004; 845p. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, L.R.; Newell, D.W.; Boyd, D.W.; Branson, C.C.; Casey, R.; Chavan, A.; Coogan, A.H.; Dechaseaux, C.; Fleming, C.A.; Haas, F.; et al. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology; Mollusca 6, Bivalvia; Moore, R.C., Ed.; The Geological Society of America, Inc. & The University of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1969; Part N, Volumes 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, A.; Calzada, S.; Otaño, L.; Carrasco, J.F. Presencia de Exogyra (Costagyra) olisiponensis en el Cenomaniense de Villarroya. Scr. Musei Geol. Semin. Barc. [Ser. Palaeontológica] 2021, XXVII, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal-Casero, M.; Barroso-Barcenilla, F.; Callapez, P.; García Joral, G.; Segura, M. Bioestratigrafía de macrofósiles del Cenomaniense superior-Turoniense inferior en el área de Santamera y Riofrío del Llano (Guadalajara, España). Rev. Soc. Geol. España 2013, 26, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Moratilla-García, M.; Barroso-Barcenilla, F.; Callapez, P.; García Joral, F.; Segura, M. Nuevos datos paleontológicos sobre el Cretácico Superior de Pálmaces de Jadraque y Veguillas (Guadalajara, España). Boletín de la Real Sociedad de España de Historia Natural. Sección Geolología 2015, 109, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Callapez, P.M. Estudo Paleoecológico dos Calcários de Trouxemil (CenomanianoTuroniano) na Região Entre a Mealhada e Condeixa-a-Nova (Portugal Central). Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 1992. 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, A.F. Estudo das formações pós-jurássicas das regiões de entre Sargento-Mor e Montemoro-Velho (margem direita do Rio Mondego). Memórias E Notícias 1966, 62, 1–343. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada, S.; Carrasco, J.F. Sobre dos Bivalvos del Cretácico superior pirenaico. Ballateria Mus. Geológico Semin. Barc. 2019, 15, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lazo, D.G. The bivalve Pholadomya gigantea in the Early Cretaceous of Argentina: Taxonomy, Taphonomy, and Paleogeographic Implications. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 2007, 52, 375–390. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes Knight, J.; Cox, L.R.; Myra Keen, A.; Smith, A.G.; Batten, L.R.; Yochelson, E.L.; Ludbrook, N.H.; Robertson, R.; Yonge, C.M.; Moore, R.C. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology Part I. Mollusca 1. Mollusca-General Features, Scaphopoda, Amphineura, Monoplacophora, Gastropoda-General Features, Archaeogastropoda and Some (Mainly Paleozoic), Caenogastropoda and Opisthobranchia; Moore, R.C., Ed.; The Geological Society of America, Inc.: Boulder, CO, USA; The University of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, D. On Tylostoma, a proposed genus of gasteropodous mollusks. Q. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 1849, 5, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callapez, P.; Ferreira Soares, A. O género Tylostoma Sharpe, 1849 (Mollusca, Gastropoda) no Cenomaniano de Portugal. In Menórias e Notícias; Publicaçȏes do Museu e Laboratório Mineralógico o Geológico da Universidad de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 1991; pp. 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet, P.; Rocroi, J.P. Classification and nomenclature of gastropod families. Malacología 2005, 47, 1–397. [Google Scholar]

- Fell, H.B.; Pawson, D.L. Systematic descriptions. In Treatise Invertebr. Paleontol. Part U Echinodermata; Moore, R.C., Ed.; Geological Society of America & University of Kansas Press: Lawrence, KN, USA, 1966; Volume 3, pp. U375–U440. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, A.F.; Marques, L.F. Os equinídeos cretácicos da região do Rio Mondego (Estudo sistemático). Memórias e Notícias 1973, 75, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, R. Cenomanian echinoids from Southern Jordan. Neues Jahrb. Für Geol. Und Paläontologie Monatshefte 2003, 2, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroi-Gourhan, A.; Leroi-Gorhan, A. Chronologie des grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure (Yonne). Gallia Préhistoire 1964, 7, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborin, Y. La parure en coquillages au Paléolithique. In Proceedings of the XXIX ème supplément à Gallia Préhistoire. 1993. 528p. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/galip_0072-0100_1993_sup_29_1 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Efrati, B.; Barkai, R.; Nunziante Cesaro, S.; Venditti, F. Function, Life Histories, and Biographies of Lower Paleolithic Patinated Flint Tools from Late Acheulian Revadim, Israel. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, S.M. Interpreting Objects and Collections; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 157–159. ISBN 978-0-203-42827-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ijams Spaid, B. Exploring Consumer Collecting Behavior: A Conceptual Model and Research Agenda. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordsletten, A.E.; Mataix-Cols, D. Hoarding Versus Collecting: Where Does Pathology Diverge from Play? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formanek, R. Why They Collect: Collectors Reveal their Motivations. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1991, 6, 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Simón-Vallejo, M.D.; Cortés-Sánchez, M.; Finlayson, G.; Giles-Pacheco, F.; Rodríguez-Vidal, J.; Calle, L.; Guillamet, E.; Finlayson, C. Hands in the dark. Palaeolithic rock art in Gorham’s Cave (Gibraltar). SPAL 2018, 27, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaubert, J.; Verheyden, S.; Genty, D.; Soulier, M.; Cheng, H.; Blamart, D.; Burlet, C.; Camus, H.; Delaby, S.; Deldicque, D.; et al. Early Neanderthal Constructions Deep in Bruniquel Cave in Southwestern France. Nature 2016, 534, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, E. Can the Collecting Instinct Be Utilized in Teaching? Elem. Sch. Teach. 1906, 9, 466–471. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/992552 (accessed on 19 April 2023). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).