Abstract

This paper reviews the principles behind the design and operation of the resistive barrier discharge, a low temperature plasma source that operates at atmospheric pressure. One of the advantages of this plasma source is that it can be operated using either DC or AC high voltages. Plasma generated by the resistive barrier discharge has been used to efficiently inactivate pathogenic microorganisms and to destroy cancer cells. These biomedical applications of low temperature plasma are of great interest because in recent times bacteria developed increased resistance to antibiotics and because present cancer therapies often are accompanied by serious side effects. Low temperature plasma, such the one generated by the resistive barrier discharge, is a technology that can help overcome these healthcare challenges.

Keywords:

low temperature plasma; barrier discharge; cells; bacteria; apoptosis; cancer; reactive species 1. Introduction

One of the most widely used approaches to generate low temperature atmospheric pressure plasmas is the dielectric barrier discharge (DBD). The dielectric barrier discharge original concept, which was first developed by Du Moncel in 1855 [1], was further developed, improved, and its physics elucidated by several investigators [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. In its most basic form the DBD uses a dielectric to cover one or two metal electrodes, which are separated by a small gas gap. The electrodes are driven by voltages of several kV at frequencies in the kHz range. Atmospheric pressure plasmas generated by DBDs have been extensively used in material processing, surface modification, as UV-VUV sources, as flow control actuators, the generation of ozone [18,19,20], and since the mid-1990s in biomedical applications [21].

One of the DBD limitations is that it needed to be operated with frequencies ranging from the kHz to the MHz. This required special high voltage power supplies at those frequencies, which added to the complexity of operating a DBD-based system. This shortcoming was overcome by replacing the dielectric barrier covering the electrodes by a high resistivity layer. Doing so allowed the extension of the frequency range all the way down to 0 Hz (DC) [22]. This paper first discusses the basic principles of operation of such resistively stabilized discharge and then a brief overview of its use in biomedical applications is presented.

2. Mechanism of Operation of the Resistive Barrier Discharge

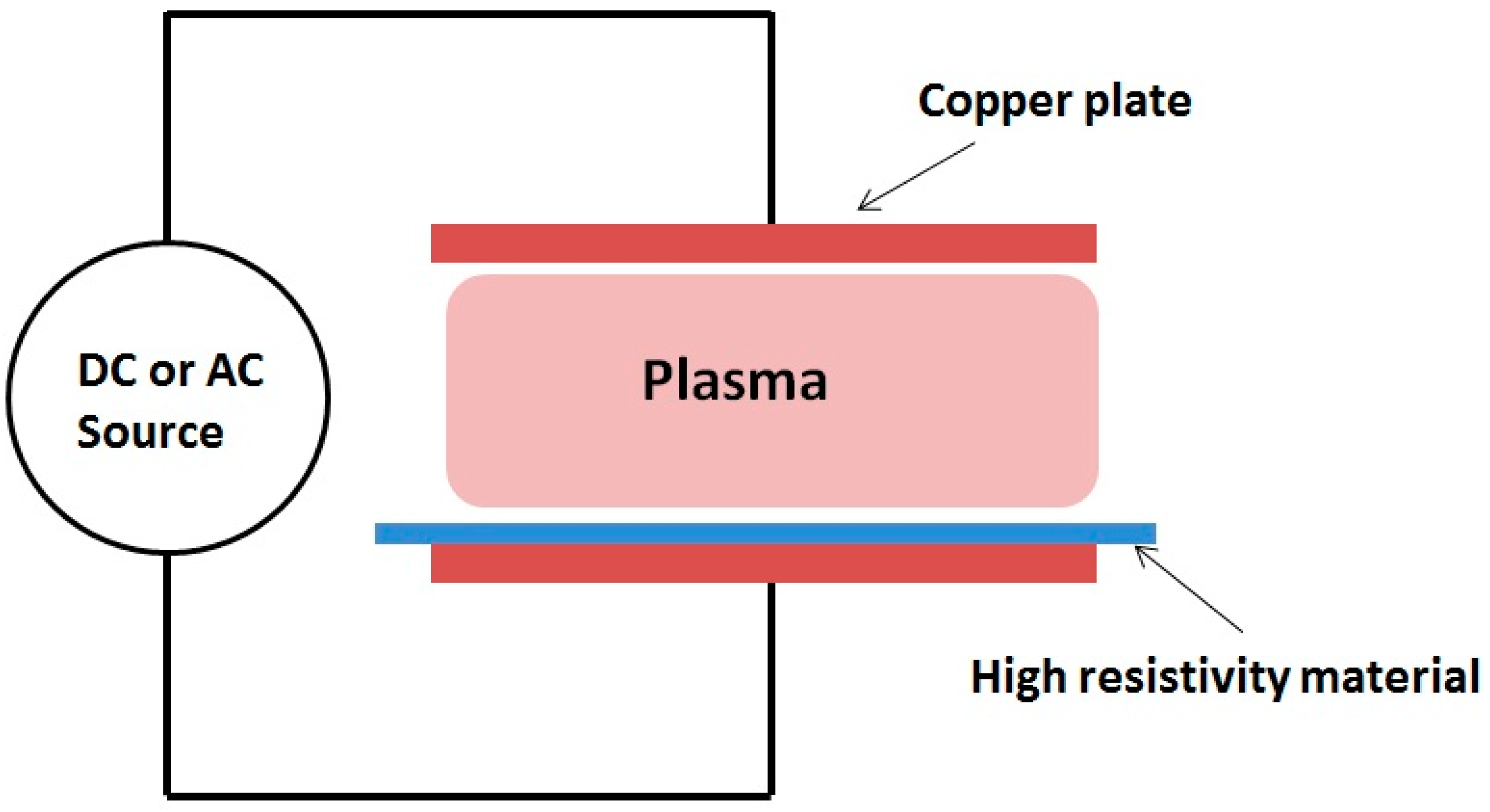

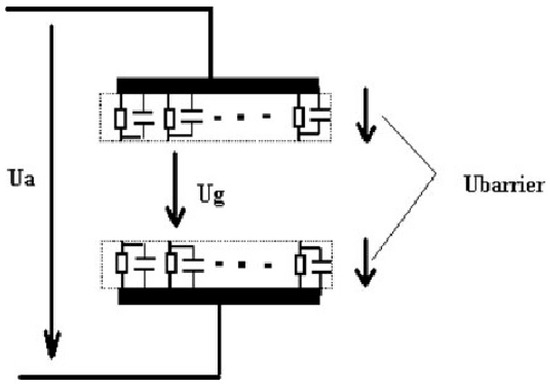

Few methods can be used to extend the operating frequency range of barrier discharges. One approach was the use of dielectric wire mesh electrode in a DBD to generate a glow discharge at a frequency of 50 Hz [23]. Laroussi and Alexeff developed another method to design a device that is known as the resistive barrier discharge (RBD) [22]. The RBD can be operated with DC or AC (50 or 60 Hz) power supplies. This discharge is somewhat similar to the DBD configuration, but instead of a dielectric barrier, a high resistivity (few MΩ.cm) sheet/layer is used to cover one of the electrodes (see Figure 1). The high resistivity sheet plays the role of a distributed resistive ballast, which helps avoid the discharge from localizing and inhibits the current from increasing to high values and turning the discharge into an arc. If helium gas was used and if the electrodes gap distance was below 5 cm, relatively uniform plasma could be maintained (see Figure 2). However, if air (>1%) was added to helium the discharge formed filaments which randomly appeared within the bulk of the volumetric plasma.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the resistive barrier discharge.

Figure 2.

Photograph of the plasma generated by a resistive barrier discharge (RBD) in helium. The gap distance between the electrodes is 4.5 cm, and the voltage is 13 kV RMS at 60 Hz [22]. The input power is around 100 W.

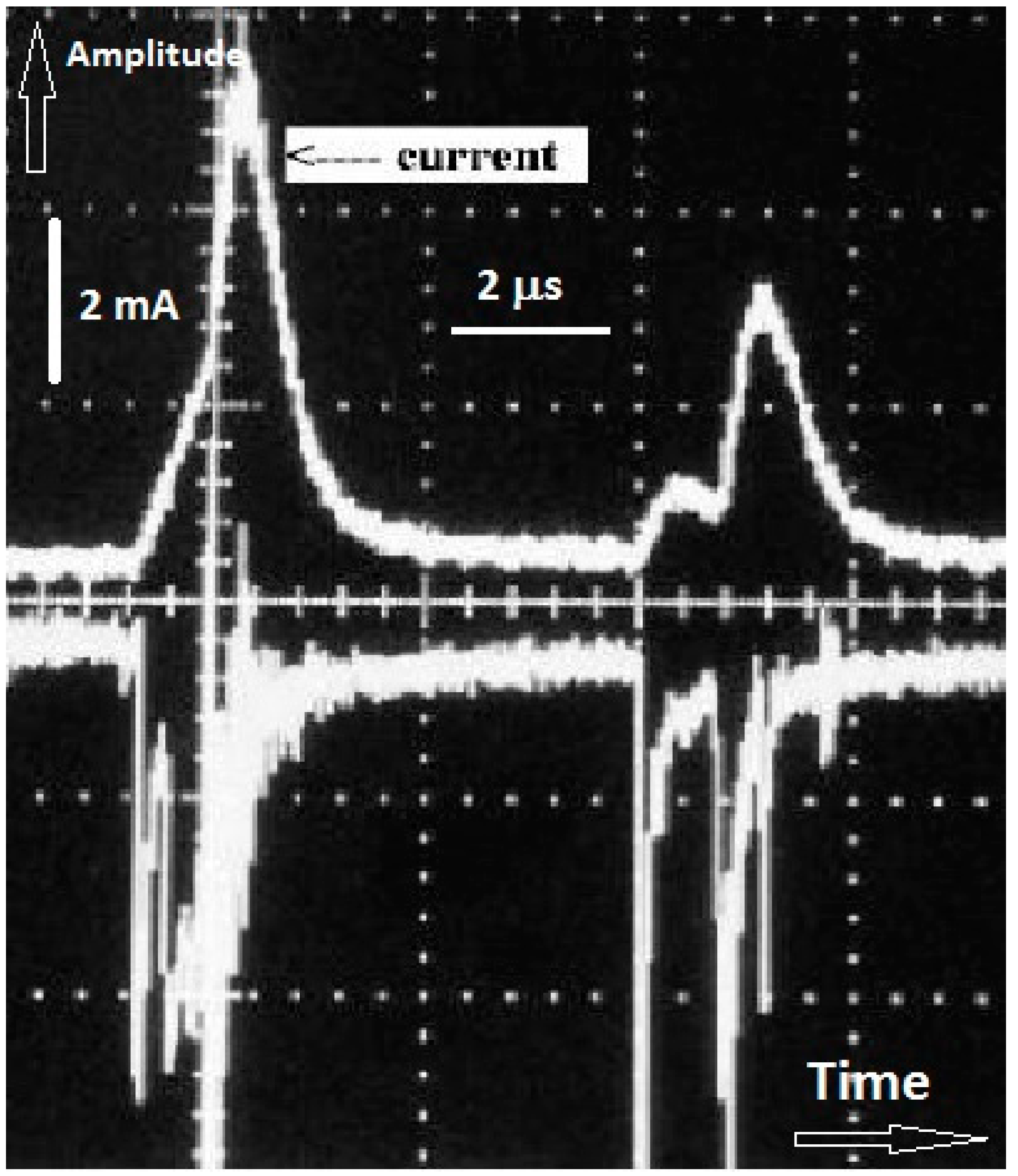

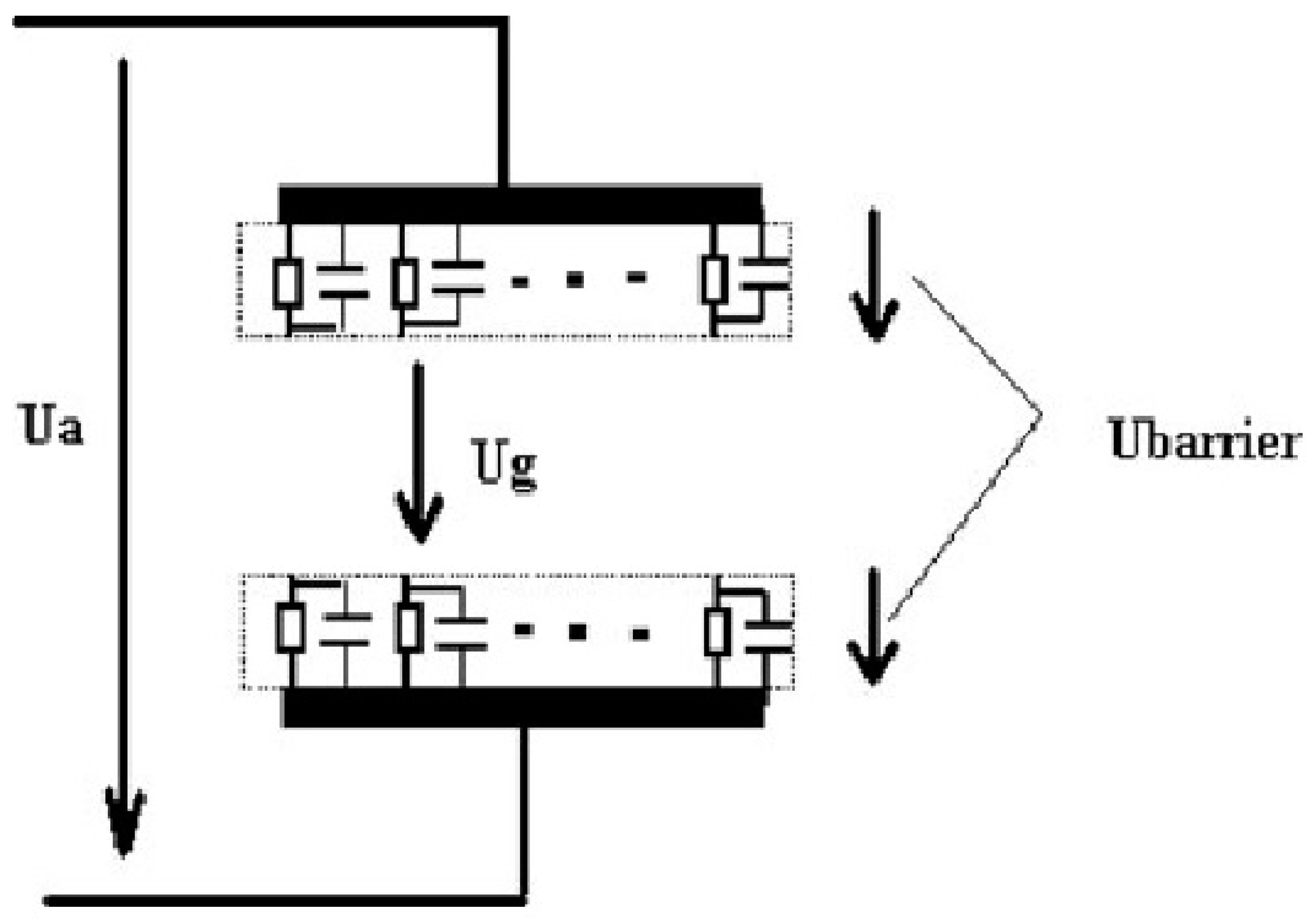

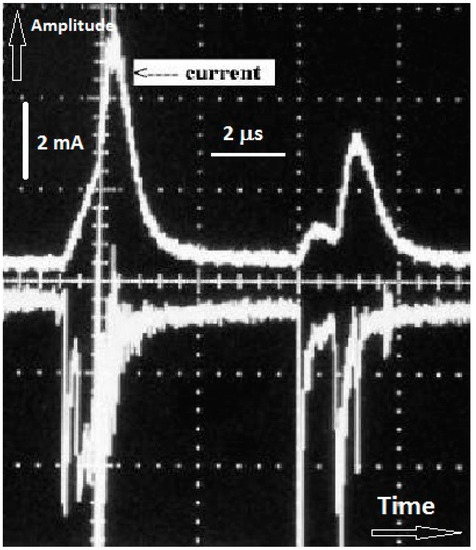

The RBD can be operated under DC or AC excitation modes. Under both modes, the discharge current exhibits a series of pulses, suggesting that like the DBD, the RBD is also a self-pulsed discharge. Figure 3 shows a typical current characteristics (top waveform) under DC excitation and the corresponding light emission intensity (bottom waveform) detected by a photomultiplier tube (PMT). The current pulses are few microseconds wide and occur at a repetition rate of few tens of kHz. The pulsing of the discharge current can be explained by a combined resistive and capacitive model of the device. When the gas breaks down and a current of sufficient magnitude flows, the equivalent capacitance of the electrodes becomes charged to the point where most of the applied voltage appears across the resistive layer of the electrodes. The voltage across the gas gap then becomes insufficient to maintain gas breakdown. At this point, the equivalent capacitor discharges itself through the resistive layer. This results in a decrease of the voltage across the resistive layer and an increase in the voltage across the gas gap and breakdown occurs again. Figure 4 shows an electrical model of the RBD [24].

Figure 3.

Current waveform (top curve) of a DC-powered (20 kV) RBD and discharge integrated light intensity detected by a photomultiplier tube (PMT) (curve is inverted to visually distinguish it from the current waveform). Note the correlation between the timing of the current and light pulses.

Figure 4.

Electrical model of the RBD [24].

3. Biomedical Applications of the RBD

Since the mid-1990s low temperature plasma (LTP) has been used for various biomedical applications including the inactivation of bacteria, wound healing, and the destruction of cancer cells and tumors [21,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. LTP was found to provide a rich cocktail of reactive species, such as reactive oxygen species, ROS, and reactive nitrogen species, RNS, that can interact with cells and tissues and induce biological effects [32]. The RBD offers a practical method to generate large volumes of low temperature atmospheric pressure plasma for many of the above-mentioned biomedical applications. The earliest work reported on the use of the RBD to inactivate bacteria [33,34,35,36,37].

Richardson et al. used the RBD to inactivate both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [33]. They showed that the decimal value (D-value) varies from several tens of seconds to several minutes depending on the type of bacteria and medium supporting the cells. Laroussi et al. used the RBD to study the effect of cold plasma on the heterotrophic pathways and morphology of bacteria [34]. As representative bacteria they used Escherichia. coli (Gram-negative) and Bacillus subtilis (Gram-positive). They addressed these questions by using sole carbon substrate utilization (SCSU) and electron microscopy. They reported that sub-lethally cold plasma can affect cells’ enzyme functions and for longer exposure to plasma E. coli underwent lysis. Although inactivated, B. subtilis cells were not necessarily lysed [34]. Laroussi et al. also reported that the lysing of cells could be explained by charge accumulation on the cell’s outer membrane [35]. This causes the creation of an outward electrostatic tension that stretches the membrane. The magnitude of this force is a function of the surface potential and is greater for a smaller radius of curvature. So in location where this radius is very small the electrostatic force can overcome the tensile strength of the membrane and therefore causes local disruption [35]. They argued that the outer membrane of E. coli exhibits an irregular/rough surface with small “bumps/pimples” with very small radii of curvature. This, they argue, why it is easier to lyse Gram-negative bacteria [35]. It is important to note here that the lysing of cells could happen because of other causes such as the oxidation and/or peroxidation reactions in the cell membrane. In addition electroporation that is caused by the presence of electric fields can lead to the opening of pores in the cell membrane, some of which may be irreversible.

Thyigarajan et al. used the RBD in helium and air to inactivate E. coli. They reported total killing of the bacterial population in 180 s (but they did not specify the original concentration) [36]. They detected high concentrations of ozone and traces of NO2. They attributed these species to the efficient inactivation they observed [36].

Uhm et al. reported on a sterilization chamber that uses several layers of RBDs to generate large volume plasmas (40 L) [37]. They used this chamber to sterilize medical tools wrapped in hospital cloths, to sterilize manufactured drugs in typical packaging materials, and to sterilize biologically contaminated article [37]. As operating gas they used oxygen and therefore created mostly ozone to interact with items to be sterilized. It took an applied power of 60 W and residence time of 5 h to accomplish sterilization [37]. They also used an ozone destruction device to eliminate the ozone after usage.

Thyiagarajan et al. used an RBD specifically designed to mostly produce RNS to study their effect on human myeloid leukemia cells [38]. The effect of variable treatments of plasma-generated RNS was tested in THP-1 cells (human monocytic leukemia cell line), a model for hematological malignancy. These investigators used erythrosine-B staining to evaluate the number of viable cells. Apoptosis and necrosis were assessed by endonuclease cleavage observed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Cells detection was done with propidium iodide (exclusionary dye) and fluorescently labeled annexin-V by flow cytometry and fluorescent microscopy [38]. They reported that treatment times less than 45 s induced apoptotic cell death while for times equal or greater than 50 s necrosis was observed. They suggested that these effects were due to the RNS generated by the RBD, however, they did not specify the specific nitrogen species.

4. Conclusions

The resistive barrier discharge is a unique LTP source capable of generating large volumes of plasma that can be used for various industrial and biomedical applications. The fact that line frequency (50 or 60 Hz) can be used with a simple step-up transformer to deliver electrical power to the discharge makes this device extremely practical. The RBD has been used in various experiments to inactivate bacteria on surfaces, in liquids, and in air. In fact, it has already been used for several years as part of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems to clean the air from biological contaminants. Finally, the RBD has been used in studies aimed at elucidating the effects of low temperature plasma on cancer cells.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Du Moncel, T.H. Notice sur L’appareil D’induction Electrique de Ruhmkorff et Sur les Experiences que L’on Peut Faire Avec Cet Instrument; Hachette et Cie Publishers: Paris, France, 1855. [Google Scholar]

- Von Siemens, W. Ueber die elektrostatische Induction und die Verzögerung des Stroms in Flaschendrähten. Poggendorfs Ann. Phys. Chem. 1857, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, S.; Kogoma, M.; Moriwaki, T.; Okazaki, S. Stable Glow Plasma at Atmospheric Pressure. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1988, 21, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massines, F.; Mayoux, C.; Messaoudi, R.; Rabehi, A.; Ségur, P. Experimental Study of an Atmospheric Pressure Glow Discharge Application to Polymers Surface Treatment. In Proceedings of the GD-92, Swansea, UK, 13–18 September 1992; Volume 2, p. 730. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, J.R.; Laroussi, M.; Liu, C. Experimental Generation of a Steady-State Glow Discharge at Atmospheric Pressure. In Proceedings of the 27th IEEE International Conference Plasma Science, Tampa, FL, USA, 1–3 June 1993; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Bartnikas, R. Note on Discharges in Helium Under AC Conditions. Brit. J. Appl. Phys. J. Phys. D. 1968, 1, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, K.G. The Development and Characterization of an Atmospheric Pressure Nonequilibrium Plasma Chemical Reactor. Ph.D. Thesis, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, T.; Kogoma, M.; Moriwaki, T.; Okazaki, S. The Mechanism of the Stabilized Glow Plasma at Atmospheric Pressure. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1990, 23, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massines, F.; Rabehi, A.; Decomps, P.; Gadri, R.B.; Ségur, P.; Mayoux, C. Experimental and Theoretical Study of a Glow Discharge at Atmospheric Pressure Controled by a Dielectric Barrier. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 8, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, B.; Egli, W.; Kogelschatz, U. Modelling of Dielectric Barrier Discharge Chemistry. Pure Apll. Chem. 1994, 66, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, N.; Gouda, G.; Gat, E.; Ricard, A.; Massines, F. Transition from glow silent discharge to micro-discharges in nitrogen gas. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2000, 9, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheradi, N.; Massines, F. Mechanisms controlling the transition from glow silent discharge to streamer discharge in nitrogen. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2001, 29, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.J.; Deng, X.T.; Hall, R.; Punnett, J.D.; Kong, M. Three modes in a radio frequency atmospheric pressure glow discharge. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 94, 6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massines, F.; Gherardi, N.; Naude, N.; Segur, P. Glow and Townsend dielectric barrier discharge in various atmosphere. Plasma Phys. Contrl. Fusion 2005, 47, B557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelschatz, U.; Eliasson, B.; Egli, W. Dielectric Barrier Discharges: Principle and Applications. J. Phys. IV 1997, C4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelschatz, U. Filamentary, Patterned, and Diffuse Barrier Discharges. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2002, 30, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, R. Dielectric barrier discharges: Progress on plasma sources and on the understanding of regimes and single filaments. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2017, 26, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Kogelschatz, U.; Schoenbach, K.H.; Barker, R.J. (Eds.) Non-equilibrium Air Plasmas at Atmospheric Pressure; IOP Pub.: Bristol, UK, 2005; ISBN 0750309628. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, J.R.; Sherman, D.N.; Wilkinson, S.P. Electrohydrodynamic Flow Control with a Glow-Discharge Surface Plasma. AIAA J. 2000, 38, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelschatz, U. Silent discharges for the generation of ultraviolet and vacuum ultraviolet excimer radiation. Pure Appl. Chem. 1990, 62, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M. Sterilization of Contaminated Matter with an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 1996, 24, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M.; Alexeff, I.; Richardson, J.P.; Dyer, F.F. The Resistive Barrier Discharge. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2002, 30, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S.; Kogoma, M.; Uehara, M.; Kimura, Y. Appearance of a Stable Glow Discharge in Air, Argon, Oxygen and Nitrogen at Atmospheric Pressure using a 50 Hz Source. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1993, 26, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, C.; Lu, M.; Pu, Y. Study on Atmospheric Pressure Glow Discharge. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2003, 12, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M. Low Temperature Plasma-Based Sterilization: Overview and State-of-the-Art. Plasma Proc. Polym. 2005, 2, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, G.; Friedman, G.; Gutsol, A.; Shekhter, A.B.; Vasilets, V.N.; Fridman, A. Applied plasma medicine. Plasma Process. Polym. 2008, 5, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M. Low Temperature Plasmas for Medicine. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2009, 37, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Woedtke, T.; Reuter, S.; Masur, K.; Weltmann, K.-D. Plasma for Medicine. Phys. Repts. 2013, 530, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbary, G.; Morfill, G.; Schmidt, H.U.; Georgi, M.; Ramrath, K.; Heinlin, J. A first prospective randomized controlled trial to decrease bacterial load using cold atmospheric argon plasma on chronic wounds in patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 163, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keidar, M.; Walk, R.; Shashurin, A.; Srinivasan, P.; Sandler, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Ravi, R.; Guerrero-Preston, R.; Trink, B. Cold plasma selectivity and the possibility of a paradigm shift in cancer therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barekzi, N.; Laroussi, M. Effects of Low Temperature Plasmas on Cancer Cells. Plasma Process. Polym. 2013, 10, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Naidis, G.V.; Laroussi, M.; Reuter, S.; Graves, D.B.; Ostrikov, K. Reactive Species in Non-equilibrium Atmospheric Pressure Plasma: Generation, Transport, and Biological Effects. Phys. Rep. 2016, 630, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Dyer, F.; Dobbs, F.C.; Alexeff, I.; Laroussi, M. On the Use of the Resistive Barrier Discharge to Kill Bacteria: Recent Results. In Proceedings of the International Conference Plasma Science, New Orleans, LA, USA, 4–7 June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Laroussi, M.; Richardson, J.P.; Dobbs, F.C. Effects of Non-Equilibrium Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas on the Heterotrophic Pathways of Bacteria and on their Cell Morphology. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 81, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M.; Mendis, D.A.; Rosenberg, M. Plasma Interaction with Microbes. New J. Phys. 2003, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagrajan, M.; Alexeff, I.; Parameswaran, S.; Beebe, S. Atmospheric pressure resistive barrier cold plasma for biological decontamination. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2005, 33, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, H.S.; Kang, J.G.; Choi, E.H.; Cho, G.S. Sterilization of medical equipment and contaminated articles by making use of a resistive barrier discharge. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2012, 61, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagrajan, M.; Anderson, H.; Gonzales, X.F. Induction of apoptosis in human myeloid leukemia cells by remote exposure of resistive barrier cold plasma. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 11, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).