Soil as an Environmental Reservoir for Baculoviruses: Persistence, Dispersal and Role in Pest Control

Abstract

:List of Abbreviations and Virus Names Mentioned in this Review

| Genus: Alphabaculovirus | |

| AcMNPV | Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| AgMNPV | Anticarsia gemmatalis multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| ArviNPV | Arctia virginalis nucleopolyhedrovirus * |

| CfMNPV | Choristoneura fumiferana multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| ChinNPV | Chrysodeixis includens nucleopolyhedrovirus (1) |

| HearNPV | Helicoverpa armigera nucleopolyhedrovirus (2) |

| HycuNPV | Hyphantria cunea nucleopolyhedrovirus * |

| HypuNPV | Hyblaea puera nucelopolyhedrovirus * |

| LaflNPV | Lambdina fiscellaria lugubrosa nucleopolyhedrovirus * |

| LdMNPV | Lymantria dispar multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| MbMNPV | Mamestra brassicae multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| MyseNPV | Mythimna separata nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| OpSNPV | Orgyia pseudotsugata single nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| PeriNPV | Pericallia ricini nucleopolyhedrovirus * |

| SeMNPV | Spodoptera exigua multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| SfMNPV | Spodoptera frugiperda multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| TnSNPV | Trichoplusia ni single nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| WisiNPV | Wiseana signata nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| Genus: Betabaculovirus | |

| PbGV | Pieris brassicae granulovirus * |

| PrGV | Pieris rapae granulovirus (3) |

| SpfrGV | Spodoptera frugiperda granulovirus |

| Genus: Gammabaculovirus | |

| GiheNPV | Gilpinia hercyniae nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| NeseNPV | Neodiprion sertifer nucleopolyhedrovirus |

| (1) Previously named Pseudoplusia includens single nucleopolyhedrovirus (PsinSNPV). (2) Previously named Heliothis zea single nucleopolyhedrovirus (HzSNPV). (3) Also named Artogeia rapae granulovirus. * not a virus species or tentative species recognized by the ICTV [1]. | |

1. Introduction

2. Baculovirus Structure and Infection Cycle

3. Detection and Quantification of OBs in Soil

3.1. Direct Counting

3.2. Insect Bioassay

3.3. PCR Amplification

4. Soil as a Virus Reservoir

5. Transport of OBs to the Soil

6. OB Dispersal in Soil

6.1. Percolation

6.2. Agricultural Operations and Livestock

6.3. Soil-Dwelling Invertebrates

7. OB Transport from Soil to Plants

7.1. Precipitation and Air Currents

7.2. Plant Height Effects

7.3. Arthropods

8. Factors That Affect Virus Persistence in Soil

8.1. Ultraviolet Radiation

8.2. Temperature

8.3. Soil pH

8.4. Moisture

8.5. Soil Type

8.6. Soil Microbiota

9. The Virus Reservoir as a Resource for Pest Control

10. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

- The physico-chemical and biological aspects of OB interactions with each of the principal components of soil (sand, silt, clay and organic matter), alone and in combination, remain largely unknown, as does the effect of the soil microbiome or plant root exudates on OB persistence. This field is set to advance rapidly with advances in metagenomics over the coming decade [144].

- Related to the previous point, environmental factors that influence OB persistence in soil have not been subjected to systematic examination or have been examined only in early studies before the adoption of modern experimental and statistical methods. Thus, even factors such as soil temperature, incident UV radiation and soil pH have not been the subject of systematic evaluation, and our understanding of these is mostly anecdotal.

- With the exception of the careful greenhouse studies on OB translocation by Fuxa, the flow of OBs from pest-infested plants to the soil, their fate in the soil and the processes that return them to the host’s foodplant are understood qualitatively, but have not been quantified. Such measurements would be of value in the parameterization of population models to identify the most influential processes driving insect disease dynamics, especially as the importance of environmental pathogen reservoirs has been questioned in the Lymantria dispar–LdMNPV pathosystem [145].

- Some early studies noted a steady decline in OB viability in soil followed by a stable OB population that did not change appreciably for many months or years (see Section 4, Figure 3). This raises the question of whether there are inherent differences in OBs that affect their stability in soil. For example, a fraction of the OBs may differ in the quantity of polyhedrin matrix or the thickness of the polyhedron envelope resulting in structures with different surface area:volume ratios that may affect their susceptibility to proteases or other enzymes produced by the soil microbiota [146]. Addressing this question may provide an additional example of the influence of OB morphology affecting the likelihood of transmission, as observed recently in a laboratory study [147].

- The impact of agrochemicals on the soil OB reservoir is unknown, although these products can have adverse effects on soil microorganisms of all types [148]. Studies on the interactions of baculoviruses with agrochemicals have mostly focused on the effects of low concentrations of insecticides that can potentiate the insecticidal activity of OBs [149,150,151,152,153,154,155]. Alternatively, the compatibility of virus-based insecticides has been evaluated against synthetic insecticides, fungicides and herbicides for application in tank mixes [156,157,158,159,160]. Most studies have reported little or no adverse effects, but where detected, these usually involved alkaline compounds that damage OB integrity [158]. The influence of copper (Cu2+), often applied as a fungicide, can vary depending on concentration [158,161,162]. Common metal ions such as Fe2+ and Fe3+ can have detrimental effects on OBs [161,163], whereas other metals may have no effect or even potentiate OB activity [163]. As the influence of plant protection products and fertilizers on OBs in soil remains entirely unknown, it would be of considerable interest to compare OB persistence in soils subjected to different fertilization regimes and pest and plant disease management strategies.

- The intriguing concept that plants can use baculoviruses as bodyguards to reduce herbivory by phytophagous insects [164] is beginning to find empirical support. Plant protection by virus bodyguards can be favored by retaining OB-contaminated foliage from one growing season to the next [80] or by adopting leaf and canopy architecture that reduces the exposure of OBs to UV radiation [164]. Alternatively, the plant could increase the host’s susceptibility to infection through the production of volatile compounds that alter the gut microbiome [165], or manipulate the insect’s feeding behavior to increase the likelihood of acquiring an infection by adjusting plant defenses [166], or by limiting the availability of new foliage [164]. Whatever the mechanisms involved, examination of the premise that the soil reservoir represents a key source of virus bodyguards that can be recruited for plant protection may provide valuable insights into the mutually beneficial nature of plant–baculovirus interactions.

- Finally, the soil is a frequently overlooked source of genetic diversity that doubtless has potential applications in the development of virus-based insecticides. Novel isolates can be obtained from soil samples when the pest is present or absent, even years after the host’s foodplant was last cultivated. The value of this approach has been demonstrated in Spodoptera spp. [42,45,137,138], but it could be applied to virus insecticides targeted at many other pests, as interactions among mixtures of virus genotypes can enhance their insecticidal properties [167].

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harrison, R.L.; Herniou, E.A.; Jehle, J.A.; Theilmann, D.A.; Burand, J.P.; Becnel, J.J.; Krell, P.J.; Van Oers, M.M.; Mowery, J.D.; Bauchan, G.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Baculoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 1185–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavy, B.; Swanson, M.M.; Taliansky, M. Viruses in soil. In Interactions in Soil: Promoting Plant Growth; Dighton, J., Adams Krumins, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 163–180. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, K.E.; Fuhrmann, J.J.; Wommack, K.E.; Radosevich, M. Viruses in Soil Ecosystems: An Unknown Quantity within an Unexplored Territory. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2017, 4, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.H.; Cory, J.S. Ecology and evolution of pathogens in natural populations of Lepidoptera. Evol. Appl. 2016, 9, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elderd, B.D. Developing Models of Disease Transmission: Insights from Ecological Studies of Insects and Their Baculoviruses. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moore, S.; Jukes, M. Advances in microbial control in IPM: Entomopathogenic viruses. In Integrated Management of Insect Pests; Kogan, M., Heinrichs, E.A., Eds.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 593–648. [Google Scholar]

- Zethner, O. Control of Agrotis segetum [Lep.: Noctuidae] root crops by granulosis virus. Entomophaga 1980, 25, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Salah, H.; Aalbu, R. Field use of granulosis virus to reduce initial storage infestation of the potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller), in North Africa. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1992, 38, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixby-Brosi, A.J.; Potter, D.A. Evaluating a naturally occurring baculovirus for extended biological control of the black cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in golf course habitats. J. Econ. Entomol. 2010, 103, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjan, D.B.; Hinchigeri, S.B. Structural Organization of Baculovirus Occlusion Bodies and Protective Role of Multilayered Polyhedron Envelope Protein. Food Environ. Virol. 2016, 8, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasque, S.N.; van Oers, M.M.; Ros, V.I. Where the baculoviruses lead, the caterpillars follow: Baculovirus-induced alterations in caterpillar behaviour. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2019, 33, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tian, Z.; Cai, L.; Shen, Z.; Michaud, J.P.; Zhu, L.; Yan, S.; Ros, V.I.D.; Hoover, K.; Li, Z.; et al. Baculoviruses hijack the visual perception of their caterpillar hosts to induce climbing behaviour thus promoting virus dispersal. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 2752–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawtin, R.E.; Zarkowska, T.; Arnold, K.; Thomas, C.J.; Gooday, G.W.; King, L.A.; Kuzio, J.A.; Possee, R.D. Liquefaction of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus-infected insects is dependent on the integrity of virus-encoded chitinase and cathepsin genes. Virology 1997, 238, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- D’Amico, V.; Slavicek, J.; Podgwaite, J.D.; Webb, R.; Fuester, R.; Peiffer, R.A. Deletion of v-chiA from a baculovirus reduces horizontal transmission in the field. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 4056–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arif, B.; Escasa, S.; Pavlik, L. Biology and Genomics of Viruses within the Genus Gammabaculovirus. Viruses 2011, 3, 2214–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bishop, D.H.L.; Entwistle, P.F.; Cameron, I.R.; Allen, C.J.; Possee, R.D. Field trials of genetically-engineered baculovirus insecticides. In The Release of Genetically Engineered Micro-Organisms; Sussman, M., Collins, C.H., Skinner, F.A., Stewart-Tull, D.E., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 143–180. [Google Scholar]

- van Oers, M.M.; Eilenberg, J. Mechanisms Underlying the Transmission of Insect Pathogens. Insects 2019, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shapiro, M. Radiation protection and activity enhancement of viruses. In Biorational Pest Control Agents: Formulation and Delivery. Am. Chem. Soc. Symp. 1995, 595, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques, R.P. Stability of insect viruses in the environment. In Viral Insecticides for Biological Control; Maramorosch, K., Sherman, K.E., Eds.; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1985; pp. 285–360. [Google Scholar]

- Cory, J.S.; Hoover, K. Plant-mediated effects in insect–pathogen interactions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasa, R.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Monribot-Villanueva, J.L.; Mercado, G.; Williams, T. Why do Spodoptera exigua multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus occlusion bodies lose insecticidal activity on amaranth (Amaranthus hypocondriacus L.)? Biol. Control 2018, 126, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminu, A.; Stevenson, P.C.; Grzywacz, D. Reduced efficacy of Helicoverpa armigera nucleopolyhedrovirus (HearNPV) on chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and other legume crops, and the role of organic acid exudates on occlusion body inactivation. Biol. Control 2023, 180, 105171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.; Bishop, J.; Page, E. Methods for the quantitative assessment of nuclear-polyhedrosis virus in soil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1980, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.F. The ecology of Mamestra brassicae NPV in soil. In Proceedings of the 5th International Colloquium on Invertebrate Pathology, Brighton, UK, 6–10 September 1982; Volume 3, pp. 493–501. [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp, W.J. Ecology of European Pine Sawfly Neodiprion sertifer (Geoff.) Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus—The Distribution and Accumulation of Viral Inclusion Bodies in Forest Soils; Forestry Canada Report FPM-X-87; Forest Pest Management Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1989; Available online: https://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/publications?id=8811 (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Mohamed, M.A.; Coppel, H.C.; Podgwaite, J.D. Persistence in Soil and on Foliage of Nucleopolyhedrosis Virus of the European Pine Sawfly, Neodiprion sertifer (Hymenoptera: Diprionidae). Environ. Entomol. 1982, 11, 1116–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.Y.; Yearian, W.C. Movement of a Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus from Soil to Soybean and Transmission in Anticarsia gemmatalis (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Populations on Soybean. Environ. Entomol. 1986, 15, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øgaard, L.; Williams, C.F.; Payne, C.C.; Zethner, O. Activity persistence of granulosis viruses [Baculoviridae] in soils in United Kingdom and Denmark. Entomophaga 1988, 33, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, H.A.; Hughes, P.R.; Shelton, A. Field Studies of the Co-Occlusion Strategy with a Genetically Altered Isolate of the Autographa californica Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus. Environ. Entomol. 1994, 23, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, C.; Scott, D. Production and persistence of the nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the Douglas-fir tussock moth, Orgyia pseudotsugata (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae), in the forest ecosystem. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1979, 33, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, W.; Gardiner, B. The persistence of a granulosis virus of Pieris brassicae in soil and in sand. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1967, 9, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaques, R.P. The persistence of nuclear-polyhedrosis virus in soil. J. Insect Pathol. 1964, 6, 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques, R.P. The persistence of a nuclear-polyhedrosis virus in the habitat of the host insect Trichoplusia ni, II Polyhedra in soil. Can. Entomol. 1967, 99, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.P.V.; Jacob, A. Persistence of the nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the rice swarming caterpillar Spodoptera mauritia (Boisduval) in soil. J. Biol. Control 1988, 2, 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, S.D.; Williams, T.; Hails, R.S.; Cory, J.S. Prey selection and baculovirus dissemination by carabid predators of Lepidoptera. Ecol. Entomol. 1996, 21, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccino, N.; Kareiva, P. Coping with a Capricious Environment: A Population Study of a Rare Pierid Butterfly. Ecology 1985, 66, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, E. Environmental persistence of the nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the European pine sawfly in relation to epizootics in Swedish Scots pine forests. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1988, 52, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.R.; Christian, P.D. A rapid bioassay screen for quantifying nucleopolyhedroviruses (Baculoviridae) in the environment. J. Virol. Methods 1999, 82, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanada, Y.; Omi, E.M. Persistence of insect viruses in field populations of alfalfa insects. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1974, 23, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo, R.; Muñoz, D.; Williams, T.; Mugeta, N.; Caballero, P. Application of the PCR–RFLP method for the rapid differentiation of Spodoptera exigua nucleopolyhedrovirus genotypes. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 135, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bonilla, Y.; López-Ferber, M.; Caballero, P.; Lery, X.; Muñoz, D. Costa Rican soils contain highly insecticidal granulovirus strains against Phthorimaea operculella and Tecia solanivora. J. Appl. Entomol. 2012, 136, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Melo-Molina, G.D.C.; Jiménez-Fernández, J.A.; Weissenberger, H.; Gómez-Díaz, J.S.; Navarro-De-La-Fuente, L.; Richards, A.R. Presence of Spodoptera frugiperda Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus (SfMNPV) Occlusion Bodies in Maize Field Soils of Mesoamerica. Insects 2023, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukuhara, T. Further studies on the distribution of a nuclear-polyhedrosis virus of the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea, in soil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1973, 22, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R.; Richter, A.R. Lack of Vertical Transmission in Anticarsia gemmatalis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus, a Pathogen Not Indigenous to Louisiana. Environ. Entomol. 1993, 22, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, R.; Muñoz, D.; Ruíz-Portero, M.C.; Alcázar, M.D.; Belda, J.E.; Williams, T.; Caballero, P. Abundance and genetic structure of nucleopolyhedrovirus populations in greenhouse substrate reservoirs. Biol. Control 2007, 42, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R.; Warren, G.W.; Kawanishi, C. Comparison of bioassay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for quantification of Spodoptera frugiperda nuclear polyhedrosis virus in soil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1985, 46, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Melchor, L.; Ramírez-Santiago, J.J.; Mercado, G.; Williams, T. Vertical dispersal of nucleopolyhedrovirus occlusion bodies in soil by the earthworm Amynthas gracilus: A field-based estimation. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante-Rodríguez, D.A.; Berber, J.J.; Mercado, G.; Valenzuela-González, J.; Muñoz, D.; Williams, T. Earthworm mediated dispersal of baculovirus occlusion bodies: Experimental evidence from a model system. Biol. Control 2016, 100, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, R.R.; Maruniak, J.E.; Funderburk, J.E. Methods for Detection of Anticarsia gemmatalis Nucleopolyhedrovirus DNA in Soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 2307–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- England, L.; Trevors, J.; Holmes, S. Extraction and detection of baculoviral DNA from lake water, detritus and forest litter. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 90, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebling, P.M.; Holmes, S.B. A refined method for the detection of baculovirus occlusion bodies in forest terrestrial and aquatic habitats. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002, 58, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokene, P.; Heldal, I.; Fossdal, C.G. Quantifying Neodiprion sertifer nucleopolyhedrovirus DNA from insects, foliage and forest litter using the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Agric. Forest Entomol. 2013, 15, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, I.; Brown, J.M.; Gitlin, S.A.; Doud, D.F. Nucleopolyhedrovirus Detection and Distribution in Terrestrial, Freshwater, and Marine Habitats of Appledore Island, Gulf of Maine. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 62, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, L.; Pollok, J.; Vincent, M.; Kreutzweiser, D.; Fick, W.; Trevors, J.; Holmes, S. Persistence of extracellular baculoviral DNA in aquatic microcosms: Extraction, purification, and amplification by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Mol. Cell. Probes 2005, 19, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.B.; Fick, W.E.; Kreutzweiser, D.P.; Ebling, P.M.; England, L.S.; Trevors, J.T. Persistence of naturally occurring and genetically modified Choristoneura fumiferana nucleopolyhedroviruses in outdoor aquatic microcosms. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.N.; Bryant, J.E.; Madsen, E.L.; Ghiorse, W.C. Evaluation and Optimization of DNA Extraction and Purification Procedures for Soil and Sediment Samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 4715–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schrader, C.; Schielke, A.; Ellerbroek, L.; Johne, R. PCR inhibitors—Occurrence, properties and removal. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trubl, G.; Roux, S.; Solonenko, N.; Li, Y.-F.; Bolduc, B.; Rodríguez-Ramos, J.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A.; Rich, V.I.; Sullivan, M.B. Towards optimized viral metagenomes for double-stranded and single-stranded DNA viruses from challenging soils. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santos-Medellin, C.; Zinke, L.A.; ter Horst, A.M.; Gelardi, D.L.; Parikh, S.J.; Emerson, J.B. Viromes outperform total metagenomes in revealing the spatiotemporal patterns of agricultural soil viral communities. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1956–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhaus, E.A. Polyhedrosis, (“Wilt Disease”) of the Alfalfa Caterpillar. J. Econ. Entomol. 1948, 41, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R. Ecology of insect nucleopolyhedroviruses. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 103, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R.; Richter, A.R. Classical biological control in an ephemeral crop habitat with Anticarsia gemmatalis nucleopolyhedrovirus. Biocontrol 1999, 44, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgwaite, J.D.; Shields, K.S.; Zerillo, R.T.; Bruen, R.B. Environmental Persistence of the Nucleopolyhedrosis Virus of the Gypsy Moth, Lymantria dispar. Environ. Entomol. 1979, 8, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, T. Viruses. In Ecology of Invertebrate Diseases; Hajek, A.E., Shapiro-Ilan, D.I., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 215–285. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques, R.P.; Harcourt, D.G. Viruses of Trichoplusia ni (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and Pieris rapae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) in Soil in Fields of Crucifers in Southern Ontario. Can. Entomol. 1971, 103, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaques, R.P. Persistence, accumulation, and denaturation of nuclear polyhedrosis and granulosis viruses. In Baculoviruses for Insect Pest Control: Safety Considerations; Summers, M., Engler, R., Falcon, L.A., Vail, P.V., Eds.; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1975; pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E.; Reichelderfer, C.F.; Heimpel, A.M. Accumulation and persistence of a nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the cabbage looper in the field. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1972, 20, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roome, R.; Daoust, R. Survival of the nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Heliothis armigera on crops and in soil in Botswana. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1976, 27, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, E. Dispersal of the nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Neodiprion sertifer from soil to pine foliage with dust. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1988, 46, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.F.; Entwistle, P.F. Epizootiology of the nuclear polyhedrosis virus of European spruce sawfly with emphasis on persistence of virus outside the host. In Microbial and Viral Pesticides; Kurstak, E., Ed.; Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 449–461. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques, R. Leaching of the nuclear-polyhedrosis virus of Trichoplusia ni from soil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1969, 13, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukuhara, T.; Namura, H. Distribution of a nuclear-polyhedrosis virus of the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea, in soil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1972, 19, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, P.J.; Young, S.Y.; Yearian, W.C. Application of a Baculovirus of Pseudoplusia includens to Soybean: Efficacy and Seasonal Persistence. Environ. Entomol. 1982, 11, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.; Matter, M.; Abdel-Rahman, A.; Micinski, S.; Richter, A.; Flexner, J. Persistence and Distribution of Wild-Type and Recombinant Nucleopolyhedroviruses in Soil. Microb. Ecol. 2001, 41, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Reichelderfer, C.F.; Heimpel, A.M. The effect of soil pH on the persistence of cabbage looper nuclear polyhedrosis virus in soil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1973, 21, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.G.; Scott, D.W.; Wickman, B.E. Long-Term Persistence of the Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus of the Douglas-Fir Tussock Moth, Orgyia pseudotsugata (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae), in Forest Soil. Environ. Entomol. 1981, 10, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, V.; Elkinton, J.S. Rainfall Effects on Transmission of Gypsy Moth (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus. Environ. Entomol. 1995, 24, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.Y. Influence of Sprinkler Irrigation on Dispersal of Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus from Host Cadavers on Soybean. Environ. Entomol. 1990, 19, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R.; Richter, A.R. Effect of Agricultural Operations and Precipitation on Vertical Distribution of a Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus in Soil. Biol. Control 1996, 6, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, V.S.; Pepi, A.; LoPresti, E.F.; Karban, R. The consequence of leaf life span to virus infection of herbivorous insects. Oecologia 2023, 201, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, S. Alternative Routes for the Horizontal Transmission of a Nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1996, 68, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindu, T.N.; Balakrishnan, P.; Sajeev, T.V.; Sudheendrakumar, V.V. Role of soil and larval excreta in the horizontal transmission of the baculovirus HpNPV and its implications in the management of teak defoliator Hyblaea puera. Curr. Sci. 2022, 122, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetter, D.L.; Bell, M.R. Natural dispersal of baculoviruses in the environment. In Viral Insecticides for Biological Control; Maramorosch, K., Shreman, K.E., Eds.; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1985; pp. 249–284. [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle, P.; Adams, P.; Evans, H. Epizootiology of a nuclear-polyhedrosis virus in European spruce sawfly (Gilpinia hercyniae): The status of birds as dispersal agents of the virus during the larval season. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1977, 29, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, P.; Forkner, A.; Green, B.M.; Cory, J.S. Avian Dispersal of Nuclear Polyhedrosis Viruses after Induced Epizootics in the Pine Beauty Moth, Panolis flammea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Biol. Control 1993, 3, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.R.; Hajek, A.E. Prey-processing by avian predators enhances virus transmission in the gypsy moth. Oikos 2012, 121, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmakoff, J.; Crawford, A.M. Enzootic virus control of Wiseana spp. in the pasture environment. In Microbial and Viral Pesticides; Kurstak, E., Ed.; Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, K.; Jayaraj, S. Effect of leaching on the movement of nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Heliothis armigera in soil. J. Biol. Control 1988, 2, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, K.; Jayaraj, S.; Subramaniam, T.R. Adsorption of polyhedra of a nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Heliothis armigera in two different types of soils. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 1987, 8, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukuhara, T.; Wada, H. Adsorption of polyhedra of a cytoplasmic-polyhedrosis virus by soil particles. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1972, 20, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagi, T. Soil column leaching of pesticides. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology; Whitacre, D., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 221, pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, P.D.; Richards, A.R.; Williams, T. Differential Adsorption of Occluded and Nonoccluded Insect-Pathogenic Viruses to Soil-Forming Minerals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4648–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, S.Y.; Yearian, W.C. Soil Application of Pseudoplusia NPV: Persistence and Incidence of Infection in Soybean Looper Caged on Soybean. Environ. Entomol. 1979, 8, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R.; Geaghan, J.P. Multiple-Regression Analysis of Factors Affecting Prevalence of Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Populations. Environ. Entomol. 1983, 12, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, N.B.; Hansen, B.M. Long-term survival and germination of Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki in a field trial. Can. J. Microbiol. 2002, 48, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Brown, I. Earthworms as phoretic hosts for Steinernema carpocapsae and Beauveria bassiana: Implications for enhanced biological control. Biol. Control 2013, 66, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capinera, J.L.; Barbosa, P. Transmission of Nuclear-Polyhedrosis Virus to Gypsy Moth Larvae by Calosoma sycophanta. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1975, 68, 593–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R. Threshold Concentrations of Nucleopolyhedrovirus in Soil to Initiate Infections in Heliothis virescens on Cotton Plants. Microb. Ecol. 2008, 55, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, R.M.; Carner, G.R.; Turnipseed, S.G. Field efficacy and persistence of a nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the velvetbean caterpillar in soybeans. J. Agric. Entomol. 1984, 1, 296–304. [Google Scholar]

- Fuxa, J.R.; Richter, A.R. Quantification of Soil-to-Plant Transport of Recombinant Nucleopolyhedrovirus: Effects of Soil Type and Moisture, Air Currents, and Precipitation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 5166–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuxa, J.R.; Richter, A.R.; Milks, M.L. Threshold distances and depths of nucleopolyhedrovirus in soil for transport to cotton plants by wind and rain. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2007, 95, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R.; Richter, A.R. Effect of nucleopolyhedrovirus concentration in soil on viral transport to cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) plants. Biocontrol 2007, 52, 821–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxa, J.R. Environmental manipulation for microbial control of insects. In Conservation Biological Control; Barbosa, P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 255–289. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, F.L.; Fuxa, J.R. Multiple Regression Analysis of Factors Influencing a Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus in Populations of Fall Armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Corn. Environ. Entomol. 1990, 19, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, R.; Martínez, A.M.; Chapman, J.W.; Magallanes, R.; Goulson, D.; Caballero, P.; Cave, R.D.; Cisneros, J.; Valle, J.; Castillejos, V.; et al. Impact of a nucleopolyhedrovirus bioinsecticide and selected synthetic insecticides on the abundance of insect natural enemies on maize in Southern Mexico. J. Econ. Entomol. 2003, 96, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.G.; Steinhaus, E.A. Further tests using a polyhedrosis virus to control the alfalfa caterpillar. Hilgardia 1950, 19, 411–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griego, V.M.; Martignoni, E.M.; Claycomb, E.A. Inactivation of nuclear polyhedrosis virus (Baculovirus subgroup A) by monochromatic UV radiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1985, 49, 709–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cherry, A.; Rabindra, R.; Parnell, M.; Geetha, N.; Kennedy, J.; Grzywacz, D. Field evaluation of Helicoverpa armigera nucleopolyhedrovirus formulations for control of the chickpea pod-borer, H. armigera (Hubn.), on chickpea (Cicer arietinum var. Shoba) in southern India. Crop. Prot. 2000, 19, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Grzywacz, D.; Curcic, I.; Scoates, F.; Harper, K.; Rice, A.; Paul, N.; Dillon, A. A novel formulation technology for baculoviruses protects biopesticide from degradation by ultraviolet radiation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhanaev, Y.B.; Belousova, I.A.; Ershov, N.I.; Nakai, M.; Martemyanov, V.V.; Glupov, V.V. Comparison of tolerance to sunlight between spatially distant and genetically different strains of Lymantria dispar nucleopolyhedrovirus. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonan, G. Soil temperature. In Climate Change and Terrestrial Ecosystem Modeling; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S. Persistence of viruses in the environment. In Factors Affecting the Survival of Entomopathogens; Baur, M.E., Fuxa, J.R., Eds.; Southern Cooperative Series Bulletin, Louisiana State University Agricultural Center: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2002; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, O.N. The effect of sunlight, ultraviolet and gamma radiations, and temperature on the infectivity of a nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1971, 18, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, D.; Mathad, S.B. Temperature tolerance, thermal inactivation and ultraviolet light resistance of nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the armyworm, Mythimna separata (Walk) (Lepid.; Noctuidae). Z. Angew. Entomol. 1978, 87, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungai, D.N.; Stigter, C.J.; Coulson, C.L.; Ng’ang’a, J.K. Simply obtained global radiation, soil temperature and soil moisture in an alley cropping system in semi-arid Kenya. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2000, 65, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, P.J.; Yearian, W.C.; Young, S.Y., III. Inactivation of Baculovirus heliothis by ultraviolet irradiation, dew, and temperature. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1977, 30, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.P.V.; Jacob, A. Studies on the nuclear polyhedrosis of Pericallia ricini F. (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae). Entomon 1976, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bustillos-Rodríguez, J.C.; Ordóñez-García, M.; Ornelas-Paz, J.D.J.; Sepúlveda-Ahumada, D.R.; Zamudio-Flores, P.B.; Acosta-Muñiz, C.H.; Gallegos-Morales, G.; Berlanga-Reyes, D.I.; Rios-Velasco, C. Effect of High Temperature and UV Radiation on the Insecticidal Capacity of a Spodoptera frugiperda Nucleopolyhedrovirus Microencapsulated in a Matrix Based on Oxidized Corn Starch. Neotrop. Entomol. 2023, 52, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, W.; Gardiner, B. The effect of heat, cold, and prolonged storage on a granulosis virus of Pieris brassicae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1967, 9, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, D.A.; Moore, N.F. Measurement of Surface Charge of Baculovirus Polyhedra. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Small, D.A.; Moore, N.F.; Entwistle, P.F. Hydrophobic Interactions Involved in Attachment of a Baculovirus to Hydrophobic Surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1986, 52, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiklander, L. Cation and anion exchange phenomena. In Chemistry of the Soil; Bear, P.E., Ed.; Von Nostrand Reinholel: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1964; pp. 163–205. [Google Scholar]

- Saikkonen, K. Nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the European pine sawfly, Neodiprion sertifer (Geoffr.) (Hym., Diprionidae) retains infectivity in soil treated with simulated acid rain. J. Appl. Entomol. 1995, 119, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Fuxa, J.R.; Richter, A.R.; Johnson, S.J. Effects of heat-sensitive agents, soil type, moisture, and leaf surface on persistence of Anticarsia gemmatalis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) nucleopolyhedrovirus. Environ. Entomol. 1999, 28, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesworth, W. Encyclopedia of Soil Science; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 902. [Google Scholar]

- Presa-Parra, E.; Lasa, R.; Reverchon, F.; Simón, O.; Williams, T. Use of biocides to minimize microbial contamination in Spodoptera exigua multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus preparations. Biol. Control 2020, 151, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, M.E. The potential role of pathogens in biological control. Nature 1989, 337, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; May, R.M. The population dynamics of microparasites and their invertebrate hosts. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1981, 291, 451–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.D. Applied epizootiology: Microbial control of insects. In Epizootiology of Insect Diseases; Fuxa, J.R., Tanada, Y., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 473–496. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardi, F. Use of viruses for pest control in Brazil: The case of the nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the soybean caterpillar, Anticarsia gemmatalis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1989, 84, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjeku, E.; Jones, K.A.; Moawad, G.M. Africa, the near and middle East. In Insect Viruses and Pest Management; Hunter-Fujita, F.R., Entwistle, P.F., Evans, H.F., Crook, N.E., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1998; pp. 280–302. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, S.; Kalmakoff, J.; Archibald, R.; Stewart, K. Density-dependent virus mortality in populations of Wiseana (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1986, 48, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepi, A.; Pan, V.; Rutkowski, D.; Mase, V.; Karban, R. Influence of delayed density and ultraviolet radiation on caterpillar baculovirus infection and mortality. J. Anim. Ecol. 2022, 91, 2192–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios-Velasco, C.; Gallegos-Morales, G.; Cambero-Campos, J.; Cerna-Chávez, E.; Del Rincón-Castro, M.C.; Valenzuela-García, R. Natural enemies of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Coahuila, México. Fla. Entomol. 2011, 94, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Velasco, C.; Gallegos-Morales, G.; Del Rincón-Castro, M.C.; Cerna-Chávez, E.; Sánchez-Peña, S.R.; Siller, M.C. Insecticidal Activity of Native Isolates of Spodoptera frugiperda Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus from Soil Samples in Mexico. Fla. Entomol. 2011, 94, 716–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vírgen, O.E.; Campos, J.C.; Bermudez, A.R.; Velasco, C.R.; Cazola, C.C.; Aquino, N.I.; Cancino, E.R. Parasitoids and Entomopathogens of the Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Nayarit, Mexico. Southwest. Entomol. 2013, 38, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Velasco, C.; Gallegos-Morales, G.; Berlanga-Reyes, D.; Cambero-Campos, J.; Romo-Chacón, A. Mortality and Production of Occlusion Bodies in Spodoptera frugiperda Larvae (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Treated with Nucleopolyhedrovirus. Fla. Entomol. 2012, 95, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Banderas, D.; Tamayo-Mejía, F.; Pineda, S.; de la Rosa, J.I.F.; Lasa, R.; Chavarrieta-Yáñez, J.M.; Gervasio-Rosas, E.; Zamora-Avilés, N.; Morales, S.I.; Ramos-Ortiz, S.; et al. Biological characterization of two Spodoptera frugiperda nucleopolyhedrovirus isolates from Mexico and evaluation of one isolate in a small-scale field trial. Biol. Control 2020, 149, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-García, M.; Rios-Velasco, C.; Ornelas-Paz, J.D.J.; Bustillos-Rodríguez, J.C.; Acosta-Muñiz, C.H.; Berlanga-Reyes, D.I.; Salas-Marina, M.Á.; Cambero-Campos, O.J.; Gallegos-Morales, G. Molecular and morphological characterization of multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus from Mexico and their insecticidal activity against Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2020, 144, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella-Saenz, I.; Herniou, E.A.; Ibarra, J.E.; Huerta-Arredondo, I.A.; Del Rincón-Castro, M.C. Virulence and genetic characterization of six baculovirus strains isolated from different populations of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, R.; Elvira, S.; Muñoz, D.; Williams, T.; Caballero, P. Genetic and phenotypic variability in Spodoptera exigua nucleopolyhedrovirus isolates from greenhouse soils in southern Spain. Biol. Control 2006, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, K.L. The Whorlworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, in Central America and Neighboring Areas. Fla. Entomol. 1980, 63, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, H.S.; Sisodiya, D.B.; Zala, M.B.; Patel, M.B.; Patel, J.K.; Patel, K.H.; Borad, P.K. Evaluation of indigenous materials against fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) in maize. Pharma Innov. J. 2021, 10, 398–404. [Google Scholar]

- Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: Disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, E.; Elderd, B.D.; Dwyer, G. Pathogen Persistence in the Environment and Insect-Baculovirus Interactions: Disease-Density Thresholds, Epidemic Burnout, and Insect Outbreaks. Am. Nat. 2012, 179, E70–E96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nannipieri, P.; Trasar-Cepeda, C.; Dick, R.P. Soil enzyme activity: A brief history and biochemistry as a basis for appropriate interpretations and meta-analysis. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2017, 54, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, E.A.; Molina-Ruíz, C.S.; Gómez-Díaz, J.S.; Williams, T. Properties of nucleopolyhedrovirus occlusion bodies from living and virus-killed larvae of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Biol. Control 2022, 174, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, A.; Gosal, S.K. Effect of pesticide application on soil microorganisms. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2011, 57, 569–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchen, B.F.; Hoover, K.; Preisler, H.K.; Betana, M.D.; Herrmann, R.; Robertson, J.L.; Hammock, B.D. Interactions of Recombinant and Wild-Type Baculoviruses with Classical Insecticides and Pyrethroid-Resistant Tobacco Budworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 1997, 90, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenhöfer, A.M.; Kaya, H.K. Interactions of a Nucleopolyhedrovirus with Azadirachtin and Imidacloprid. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2000, 75, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, A.W.; Valle, J.; Ibarra, E.J.; Cisneros, J.; Penagos, I.D.; Williams, T. Spinosad and nucleopolyhedrovirus mixtures for control of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in maize. Biol. Control 2002, 25, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Li, F.; Hu, J.; Ding, C.; Wang, C.; Tian, J.; Xue, B.; Xu, K.; Shen, W.; Li, B. Sublethal dose of phoxim and Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus interact to elevate silkworm mortality. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dáder, B.; Aguirre, E.; Caballero, P.; Medina, P. Synergy of Lepidopteran Nucleopolyhedroviruses AcMNPV and SpliNPV with Insecticides. Insects 2020, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Helaly, A.A.; Sayed, W.A.A.; El-Bendary, H.M. Impact of emamectin benzoate on nucleopolyhedrosis virus infectivity of Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2020, 30, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Lopez, Y.A.; Aldebis, H.K.; Hatem, A.E.-S.; Vargas-Osuna, E. Interactions of entomopathogens with insect growth regulators for the control of Spodoptera littoralis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Biol. Control 2022, 170, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, G. Synergism of micro-organisms and chemical insecticides. In Microbial Control of Insects and Mites; Burges, H.D., Hussey, N.W., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1971; pp. 327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques, R.P.; Morris, O.N. Compatibility of pathogens with other methods of pest control and with different crops. In Microbial Control of Pests and Plant Diseases 1970–1980; Burges, H.D., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 695–715. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, E.; Undorf-Spahn, K.; Kienzle, J.; Huber, J.; Jehle, J.A. Effect of mixtures with other products on the efficacy of codling moth granulovirus (CpGV). In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Organic Fruit-Growing (Ecofruit), Weinsberg, Germany, 20–22 February 2012; Fördergemeinschaft Ökologischer Obstbau e.V. (Foko): Weinsberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 332–337. [Google Scholar]

- Espinel, C.; Gómez, J.; Villamizar, L.; Cotes, A.M.; Léry, X.; López-Ferber, M. Biological activity and compatibility with chemical pesticides of a Colombian granulovirus isolated from Tecia solanivora. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 2009, 45, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Maciel, R.M.A.; Amaro, J.T.; Colombo, F.C.; Neves, P.M.O.J.; Bueno, A.D.F. Mixture compatibility of Anticarsia gemmatalis nucleopolyhedrovirus (AgMNPV) with pesticides used in soybean. Ciência Rural 2022, 52, e20210027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kareem, A.B.D.; Sara, M.I.; El-Banna, H.M.S. Activation of stored Spodoptera littoralis nuclear polyhedrosis virus (SpliNPV) through the addition of inorganic sulphate salts. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 95, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Wellenstein, G.; Lühl, R. Bekämpfung schädlicher Raupen mit insektenpathogenen Polyederviren und chemischen Stressoren. Naturwissenschaften 1972, 59, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M. The Effects of Cations on the Activity of the Gypsy Moth (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus. J. Econ. Entomol. 2001, 94, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, S.L.; Sabelis, M.W.; Janssen, A.; Van der Geest, L.P.S.; Beerling, E.A.M.; Fransen, J.J. Can plants use entomopathogens as bodyguards? Ecol. Lett. 2000, 3, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gasmi, L.; Martínez-Solís, M.; Frattini, A.; Ye, M.; Collado, M.C.; Turlings, T.C.; Erb, M.; Herrero, S. Can herbivore-induced volatiles protect plants by increasing the herbivores’ susceptibility to natural pathogens? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01468-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shikano, I.; Shumaker, K.L.; Peiffer, M.; Felton, G.W.; Hoover, K. Plant-mediated effects on an insect–pathogen interaction vary with intraspecific genetic variation in plant defences. Oecologia 2017, 183, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; López-Ferber, M.; Caballero, P. Nucleopolyhedrovirus Coocclusion Technology: A New Concept in the Development of Biological Insecticides. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 810026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Virus | Insect Instar Tested | Inoculation Method | Lower Threshold of Detection (OB/g Soil) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AcMNPV | first | Soil extraction + diet surface contamination | 30 | [29] |

| AgMNPV | first | Soil extraction + leaf disk contamination | 16–318 | [44] |

| HearNPV | first | Soil + diet mixture | 26–147 (1) | [38] |

| HycuNPV | fifth | Soil + diet mixture | 1.8 × 107 (2) | [43] |

| SeMNPV | first | Soil + diet mixture | 43 (3) | [45] |

| SfMNPV | first | Soil suspension on leaf disk | <10–4 × 104 (4) | [46] |

| SfMNPV | first | Soil + diet mixture | 2 × 104 | [42] |

| SfMNPV | second | Soil + diet mixture | ~5 × 103 | [47] |

| SfMNPV | second | Soil + diet mixture | 1 × 104 (5) | [48] |

| Virus | Crop or Foodplant | OB Density Estimate (OB/g Soil) (1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CfMNPV | Forest | 4.2 × 104 (2) | [50] |

| HearNPV | Sorghum | 1.6 × 104 | [68] |

| HearNPV | Sorghum, fenugreek, alfalfa | 1 × 103–1.6 × 104 | [38] |

| TnSNPV | Crucifers | 5 × 103–6 × 105 | [19] |

| NeseNPV | Pine forest | 104–105 (3) | [37,69] |

| NeseNPV | Pine forest | 1.3 × 104–1 × 105 (4) | [25] |

| NeseNPV | Pine forest | 9.4 × 104 (2) | [52] |

| SfMNPV | Maize, pastures | 2 × 104 (5) | [46] |

| SfMNPV | Maize | 104–105 | [42] |

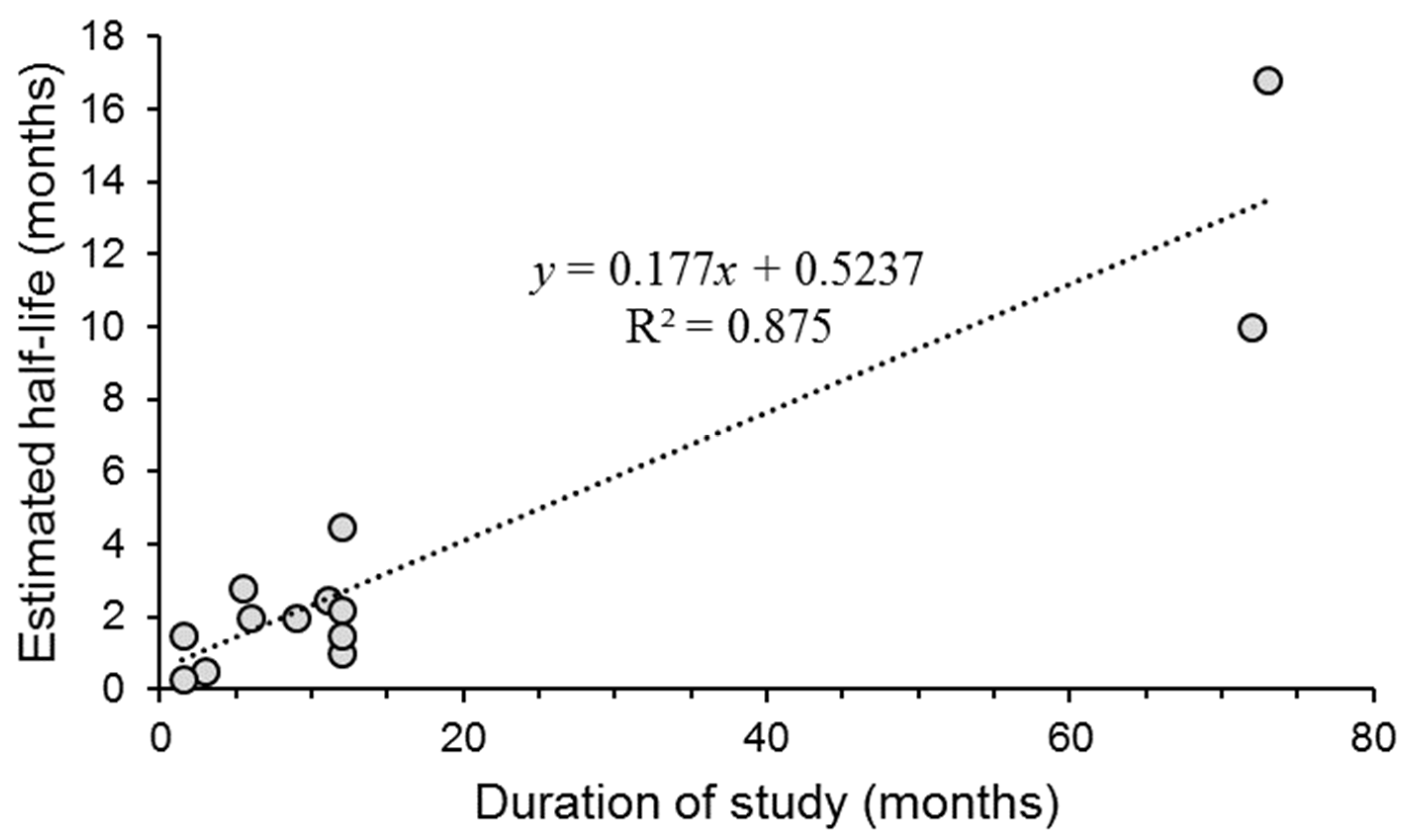

| Virus | Ecosystem | Duration of Study (Months) | Soil pH | Half-Life (t½) (1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AcMNPV | Cabbage field | 12 | - | No decay (2) | [29] |

| ChinNPV | Soybean field | 6 | - | 2 mo (3) | [73] |

| HearNPV | Sorghum plots | 5.4 | - | 2.8 mo (4) | [68] |

| HzSNPV | Cotton plots | 11 | 7.1 | 2.4–2.9 mo (5) | [74] |

| MbMNPV | Field plots | 12 | - | 2.2 mo | [24] |

| NeseNPV | Forest | 2–3.8 | - | 13–18 d (6) | [26] |

| NeseNPV | Forest | 72 | 10 mo | [37] | |

| OpSNPV | Forest | 12 | - | 26–39 d (7) | [30] |

| PbGV | Brown soil | 12 | 4.8 | 1.5 mo | [28] |

| PbGV | Sandy soil | 1.5 | 7.0 | 16–54 d | [28] |

| PbGV | Sandy loam soil | 1.5 | 7.7 | 11–13 d | [28] |

| TnSNPV | Field plots | 9 | 4.8–5.2 | 1.5–2.8 mo (8) | [75] |

| TnSNPV | Field plots | 12 | 6.0–7.2 | 3.4–5.7 mo (8) | [75] |

| TnSNPV | Field plots | 73 | - | 16.8 mo (9) | [66] |

| Virus | Temperature (°C) | Duration (h) | Wet or Dry Preparation | Effect on OB Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PeriNPV | 35 | 120 | dry | Marked reduction | [117] |

| SfMNPV | 40 | 8 | wet | 25% reduction | [118] |

| PbGV | 40 | 240 | wet | Marked reduction | [119] |

| SfMNPV | 45 | 8 | wet | 40% reduction | [118] |

| HearNPV | 45 | 24–48 | dry | 5-fold to 25-fold reduction | [116] |

| LaflNPV | 45 | 5–200 | wet | Reduced virulence | [113] |

| PbGV | 50 | 120 | wet | Almost eliminated | [119] |

| MyseNPV | 50 | 96 | dry | Almost eliminated | [114] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Williams, T. Soil as an Environmental Reservoir for Baculoviruses: Persistence, Dispersal and Role in Pest Control. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems7010029

Williams T. Soil as an Environmental Reservoir for Baculoviruses: Persistence, Dispersal and Role in Pest Control. Soil Systems. 2023; 7(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems7010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliams, Trevor. 2023. "Soil as an Environmental Reservoir for Baculoviruses: Persistence, Dispersal and Role in Pest Control" Soil Systems 7, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems7010029

APA StyleWilliams, T. (2023). Soil as an Environmental Reservoir for Baculoviruses: Persistence, Dispersal and Role in Pest Control. Soil Systems, 7(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems7010029