Abstract

Neutral organic radicals with intrinsic spin-allowed doublet emission have emerged as a promising class of luminescent materials, garnering significant research interest. However, the development of stable luminescent radicals with tunable emission remains challenging. Herein, we present the synthesis of a series of 9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-substituted fluorenyl radicals functionalized with various substituents at the 3,6-positions. These radicals exhibit enhanced stability through efficient spin delocalization and kinetic protection. Notably, they display red-shifted photoluminescence compared to traditional polychlorotriphenylmethyl radicals, with maximum emission wavelengths ranging from 679 nm to 744 nm. The mechanisms underlying the doublet emission, as well as their electrochemical properties, have been thoroughly investigated.

1. Introduction

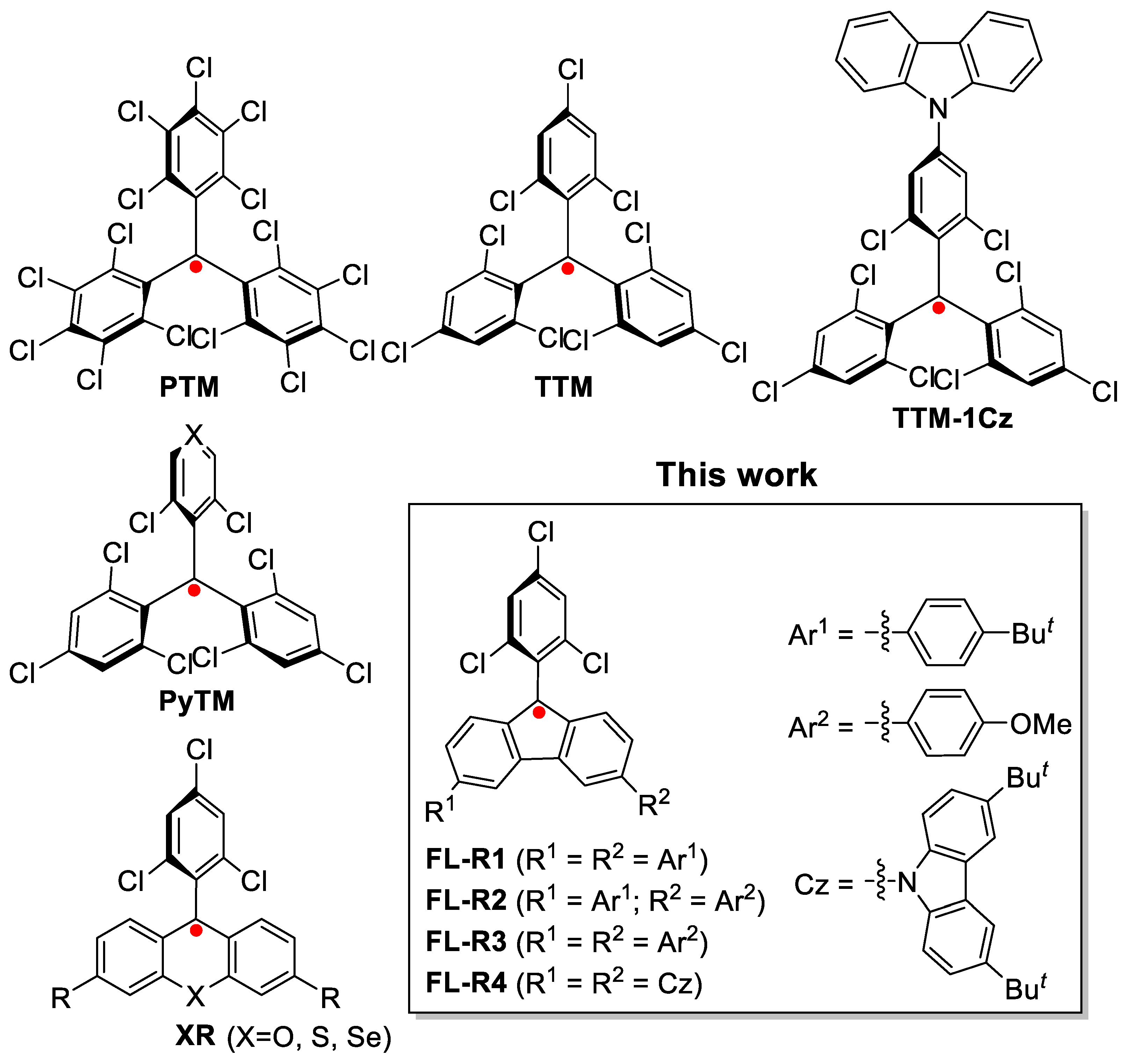

Open-shell organic radicals, characterized by one or more unpaired electrons, are unique functional materials attracting significant research interest due to their novel optoelectronic and magnetic properties. These radicals have been explored for applications in sensors [1,2,3], catalysis [4,5,6], conductive materials [7,8,9], and magnetic materials [10,11,12]. Recently, radicals with spin-allowed doublet emission have emerged as promising luminescent materials [13,14,15,16]. Highly symmetric radicals such as perchlorotriphenylmethyl (PTM) and tris(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl (TTM) (Figure 1) usually exhibit weak luminescence [17,18,19,20]. In 2006, Gamero et al. reported a carbazole-substituted tris(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl radical (TTM-1Cz) (Figure 1), which demonstrated intense red emission and enhanced photostability [21]. In 2015, Li et al. first incorporated this radical into organic light-emitting diodes, achieving a maximum external quantum efficiency of 2.4% [22]. Further studies have led to new luminescent radicals with improved device performance [13,14,23,24,25].

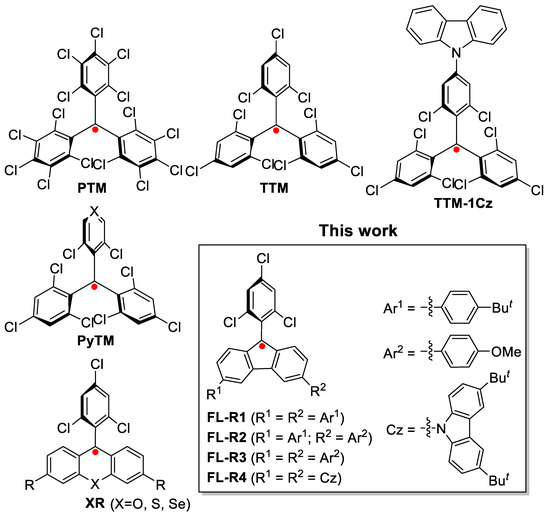

Figure 1.

The structures of some reported stable radicals with room-temperature doublet emission, and the new luminescent fluorenyl radicals in this report.

In addition, Nishihara et al. developed pyridine-substituted triarylmethyl radicals, including (3,5-dichloro-4-pyridyl)bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl (PyBTM) (Figure 1), which exhibited good stability under ambient conditions and photoirradiation [26]. PyBTM was also employed as a ligand to form metal-coordinated complexes for photophysical studies [27]. Later, they synthesized trigonal ligands such as bis(3,5-dichloro-4-pyridyl)(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl [28] and tris(3,5-dichloro-4-pyridyl)methyl radicals [29], which formed 1D and 2D coordination polymers displaying intriguing solid-state luminescence and magnetoluminescence [30].

Recently, our group reported stable xanthene radicals and their heavy chalcogen analogs (XR) (Figure 1), which exhibited tunable doublet emission spanning the visible to near-infrared (NIR) regions [31]. Stable fluorenyl radicals have been previously explored, with early reports by Ballester and co-workers highlighting their synthesis and stability [32,33]. Furthermore, some diradicaloids have been shown to demonstrate efficient NIR emission, highlighting the potential of open-shell systems for optoelectronic applications [34,35,36,37]. Building on these advances, we present a new series of 9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-substituted fluorenyl radicals (FL-R1 to FL-R4) (Figure 1). These radicals, functionalized with various substituents at the 3,6-positions, exhibit remarkable stability and tunable doublet emission spanning from the far-red to NIR regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumentation

All reagents and starting materials were obtained from commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF) was distilled from sodium–benzophenone immediately prior to use. Anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) was distilled from CaH2. All reaction conditions dealing with air- and moisture-sensitive compounds were carried out in a dry reaction vessel under a N2 atmosphere. Cyclic voltammetry measurement was performed in a dehydrated dichloromethane (DCM) solution (5 mL) on a CHI620C electrochemical analyzer (Metrohm, Singapore) with a three-electrode cell, using 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 as a supporting electrolyte, Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode, a gold disk as a working electrode, Pt wire as the counter electrode, and at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in the solution of CDCl3 and CD2Cl2 on a Bruker AVANCE (500 MHz) spectrometer (Brucker, Germany). All chemical shifts are quoted in ppm, with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. The following abbreviations were used to explain the multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, m = multiplet. High-resolution electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra were recorded on a MicrOTOFQII instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Germany). UV–vis–NIR absorption spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrophotometer (Shimazu, Japan).

2.2. Synthesis

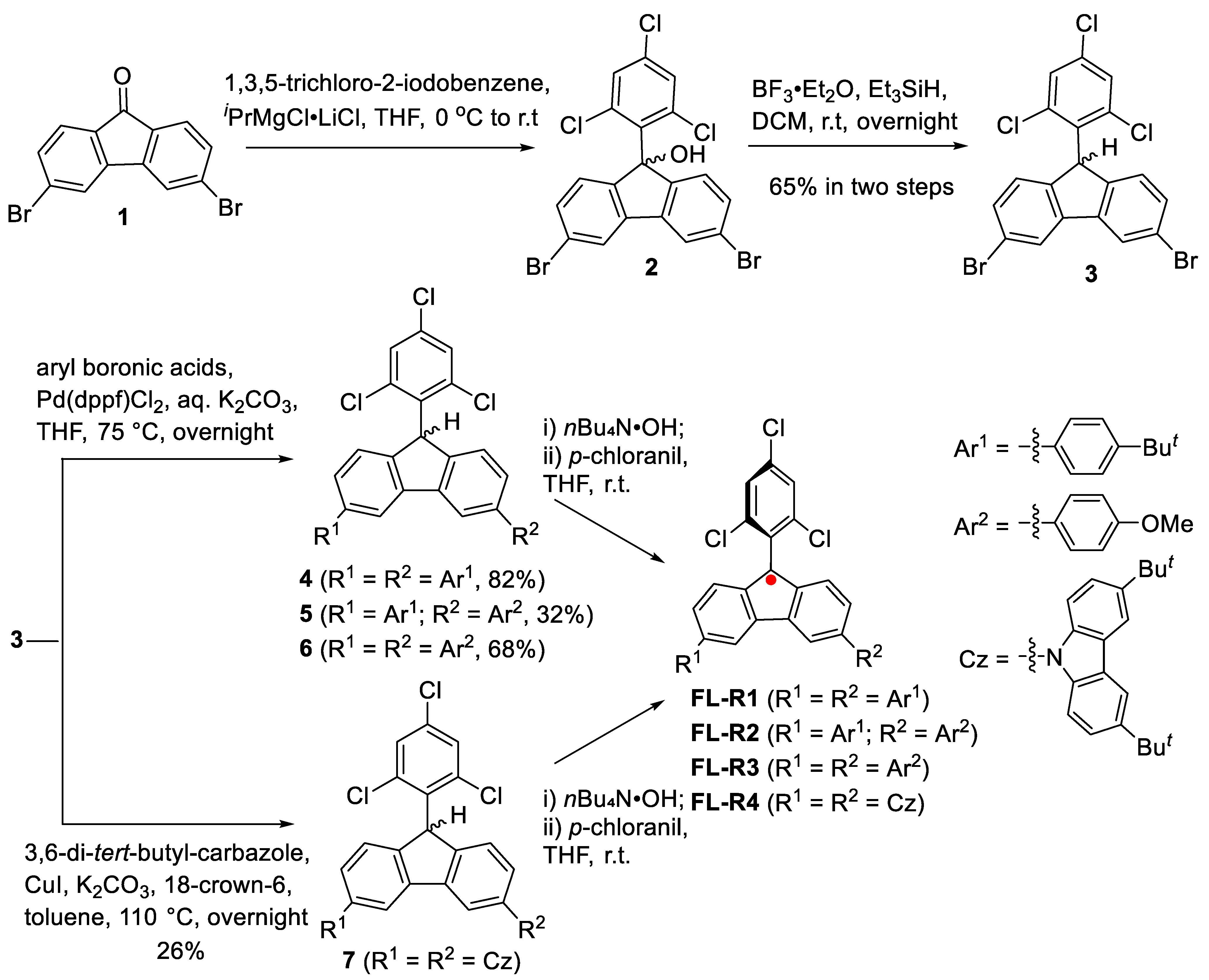

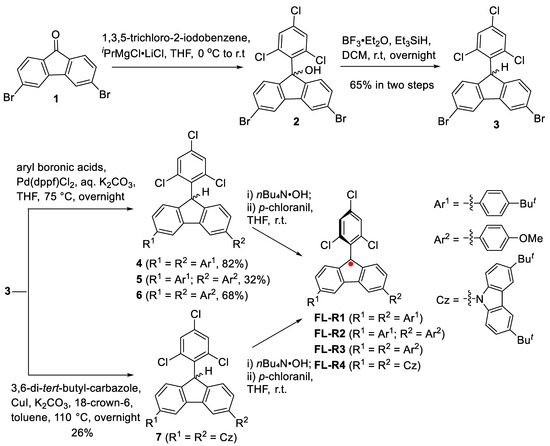

The fluorenyl radicals FL-R1 to FL-R4 were synthesized as outlined in Scheme 1. Nucleophilic addition of 3,6-dibromofluorenone (1) with in situ-generated 1,3,5-trichloro-2-phenylmagnesium chloride yielded 3,6-dibromo-9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-9-hydroxyfluorene (2). Compound 2 was then reduced to hydrofluorene (3) using boron trifluoride diethyl etherate and triethylsilane. Suzuki coupling reactions between compound 3 and various aryl boronic acids produced the precursors 4–6, while the carbazole-substituted precursor 7 was synthesized via an Ullmann-type coupling reaction. The final fluorenyl radicals were obtained by treating precursors 4–7 with a base (nBu₄N·OH), followed by oxidation with p-chloranil. The resulting radicals were purified using standard silica gel column chromatography.

Scheme 1.

The synthetic route of the new fluorenyl radicals.

3,6-Dibromo-9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-9-hydroxyfluorene (2): In a dry, nitrogen-purged round-bottom flask, 1,3,5-trichloro-2-iodobenzene (3.07 g, 10 mmol) was dissolved in 50 mL of anhydrous THF and cooled to 0 °C. Subsequently, 7.7 mL of an isopropylmagnesium chloride–lithium chloride complex solution (1.3 M in THF, 10 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was gradually warmed to room temperature and stirred for 2 h. The resulting solution was then added dropwise to a solution of compound 1 (1.68 g) in anhydrous THF (50 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h, with progress monitored by TLC. After completion, the reaction was quenched with an aqueous NH4Cl solution and extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude diol intermediate, obtained as a solid, was washed with methanol and filtered. Due to its poor solubility, it was used directly in the next synthetic step.

3,6-Dibromo-9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-9H-fluorene (3): To a solution of crude compound 2 (516 mg, 1 mmol) in 15 mL of DCM, boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (0.2 mL, 4 mmol) and triethylsilane (0.3 mL, 4 mmol) were added sequentially. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Upon completion, the reaction was quenched with water and extracted three times with DCM. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent was removed under vacuum.The crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, DCM/hexane = 1:20) to yield compound 2 as a pale-yellow powder (385 mg, 77%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 7.65 (s, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (dd, J = 1.8, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (t, J = 1.3 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.88 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 144.13, 142.69, 138.00, 136.57, 134.54, 134.12, 131.17, 130.30, 128.53, 125.75, 124.09, 122.06, 77.67, 77.42, 77.16, 49.71. HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd for C19H9Cl3Br2 [M⁺]: 499.8131, found: 499.8132 (error: −0.2 ppm).

3,6-Bis(4-(tert-butyl)phenyl)-9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-9H-fluorene (4): A two-necked round-bottom flask was charged with 4-tert-butylphenylboronic acid (391.7 mg, 2.2 mmol), compound 2 (1.0 g, 2.0 mmol), 2 M aqueous K2CO3 (5 mL), and THF (50 mL). The solution was purged with argon for 30 min. Pd(dppf)Cl2 (14.62 mg, 0.02 mmol) was then added under an argon atmosphere. The resulting mixture was heated at 75 °C overnight. After cooling to room temperature, water was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted with DCM. The organic layer was dried over sodium sulfate and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane/DCM = 2:1), yielding the pure product 4 as a white solid (3.4 g, 68%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 8.07 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H), 7.55 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 6H), 7.28 (s, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.99 (s, 1H), 1.39 (s, 18H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 150.50, 144.00, 142.17, 140.75, 138.55, 130.00, 128.13, 127.08, 126.51, 125.90, 124.17, 118.84, 49.69, 34.71, 31.54. HRMS analysis (APCI): calcd for C39H35Cl3: 608.1721; found: 508.1702; (error: −3.2 ppm).

3-(4-(tert-Butyl)phenyl)-6-(4-methoxyphenyl)-9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-9H-fluorene (5): A two-necked round-bottom flask was charged with 4-tert-butylphenylboronic acid (178 mg, 1.0 mmol), compound 2 (1.0 g, 2.0 mmol), 2 M aqueous K2CO3 (5 mL), and THF (50 mL), then purged with argon for 30 min. Pd(dppf)Cl2 (14.62 mg, 0.02 mmol) was added under an argon atmosphere. The resulting mixture was heated at 75 °C for 12 h. Subsequently, 4-methoxyphenylboronic acid (167.2 mg, 1.0 mmol) was added, and the mixture was heated at 75 °C for an additional 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, water was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted with DCM. The organic layers were combined, dried over sodium sulfate, and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane/DCM = 3:1), yielding the pure product 5 as a white solid (3.4 g, 32%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 8.07 (d, J = 1.7 Hz), 8.03 (d, J = 1.7 Hz), 7.67—7.61 (m), 7.55 (d, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.54—7.50 (m), 7.50—7.47 (m), 7.28 (d, J = 4.3 Hz), 7.17 (d, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.03—7.00 (m), 5.98, 3.88, 1.38. 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 159.06, 150.21, 143.75, 143.40, 141.92, 141.89, 140.47, 140.24, 138.26, 137.55, 136.28, 135.01, 133.75, 133.45, 129.95, 129.71, 128.19, 127.92, 127.85, 126.81, 126.60, 126.22, 125.97, 125.62, 125.16, 123.90, 123.31, 118.57, 118.26, 114.11, 67.85, 55.25, 49.38, 49.26, 31.26, 25.49. HRMS analysis (APCI): calcd for C36H29Cl3O1: 582.1200; found: 582.1206; (error: 0.2 ppm).

3,6-Bis(4-methoxyphenyl)-9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-9H-fluorene (6): A two-necked round-bottom flask was charged with 4-methoxyphenylboronic acid (334.3 mg, 2.2 mmol), compound 2 (1.0 g, 2.0 mmol), 2 M aqueous K2CO3 (5 mL), and THF (50 mL). The solution was purged with argon for 30 min. Pd(dppf)Cl2 (14.62 mg, 0.02 mmol) was then added under an argon atmosphere. The resulting mixture was heated at 75 °C overnight. After cooling to room temperature, water was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted with DCM. The organic layer was dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane/DCM = 5:1), affording the pure product 6 as a white solid (3.4 g, 77%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 8.04 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.66—7.62 (m, 4H), 7.55 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.26—7.24 (m, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.04—7.00 (m, 4H), 5.98 (s, 1H), 3.88 (s, 7H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 159.33, 143.70, 142.19, 140.51, 134.03, 133.72, 129.99, 128.47, 128.14, 126.24, 124.18, 118.55, 114.38, 55.53, 49.63. HRMS analysis (APCI): calcd for C33H24Cl3O2: 557.0844; found: 557.0836; (error: 1.44 ppm).

9,9′-(9-(2,4,6-Trichlorophenyl)-9H-fluorene-3,6-diyl)bis(3,6-di-tert-butyl-9H-carbazole) (7): A two-necked round-bottom flask was charged with 3,6-di-tert-butylcarbazole (335 mg, 1.2 mmol), compound 2 (500 mg, 1.0 mmol), CuI (19 mg, 0.10 mmol), K2CO3 (828 mg, 6.0 mmol), 18-crown-6 (26 mg, 0.10 mmol), and toluene (50 mL). The mixture was heated at 110 °C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, water was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted with DCM. The organic layer was dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane/DCM = 1:2), yielding pure compound 7 as a yellow solid (234 mg, 26%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ ppm 8.14 (dd, J = 2.0, 0.6 Hz, 4H), 7.94 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.48—7.44 (m, 6H), 7.39 (dd, J = 8.6, 0.6 Hz, 4H), 7.28 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (s, 1H), 1.45 (s, 36H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3):δ 143.69, 142.80, 142.57, 139.25, 137.82, 129.99, 128.11, 126.20, 125.06, 123.64, 123.56, 123.29, 118.67, 116.21, 116.16, 109.10, 109.06, 77.16, 76.91, 76.65, 49.63, 34.62, 31.89, 29.60. HRMS analysis (APCI): calcd for C59H57Cl3N2: 899.366; found: 899.3664; (error: 0.44 ppm).

2.3. General Procedure for Deprotonation and Oxidation

Under an argon atmosphere and in dark conditions, tetra-n-butylammonium hydroxide (3.0 eq.) was added to compounds 4, 5, 6, or 7 (1.0 eq.), each dissolved in 20 mL of dry THF. The solution quickly turned light red. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h. Subsequently, p-chloranil (4.0 eq.) was added, and the reaction was stirred for an additional 2 h. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and the crude products were purified by silica gel column chromatography using a mixture of DCM and ethyl acetate as the eluent. This process yielded the radical compounds FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 almost quantitatively.

FL-R1: Red powder; APCI (m/z): Calcd for C39H34Cl3, 607.1721; Found, 607.1728 (error: 1.15 ppm).

FL-R2: Red powder; APCI (m/z): Calcd for C36H28Cl3O1, 581.1200; Found, 581.1205 (error: 0.86 ppm).

FL-R3: Red powder; APCI (m/z): Calcd for C33H23Cl3O2, 555.0684; Found, 555.068 (error: 0.72 ppm).

FL-R4: Light blue powder; APCI (m/z): Calcd for C59H56Cl3N2, 898.3587; Found, 898.3579 (error: 0.89 ppm).

3. Results and Discussion

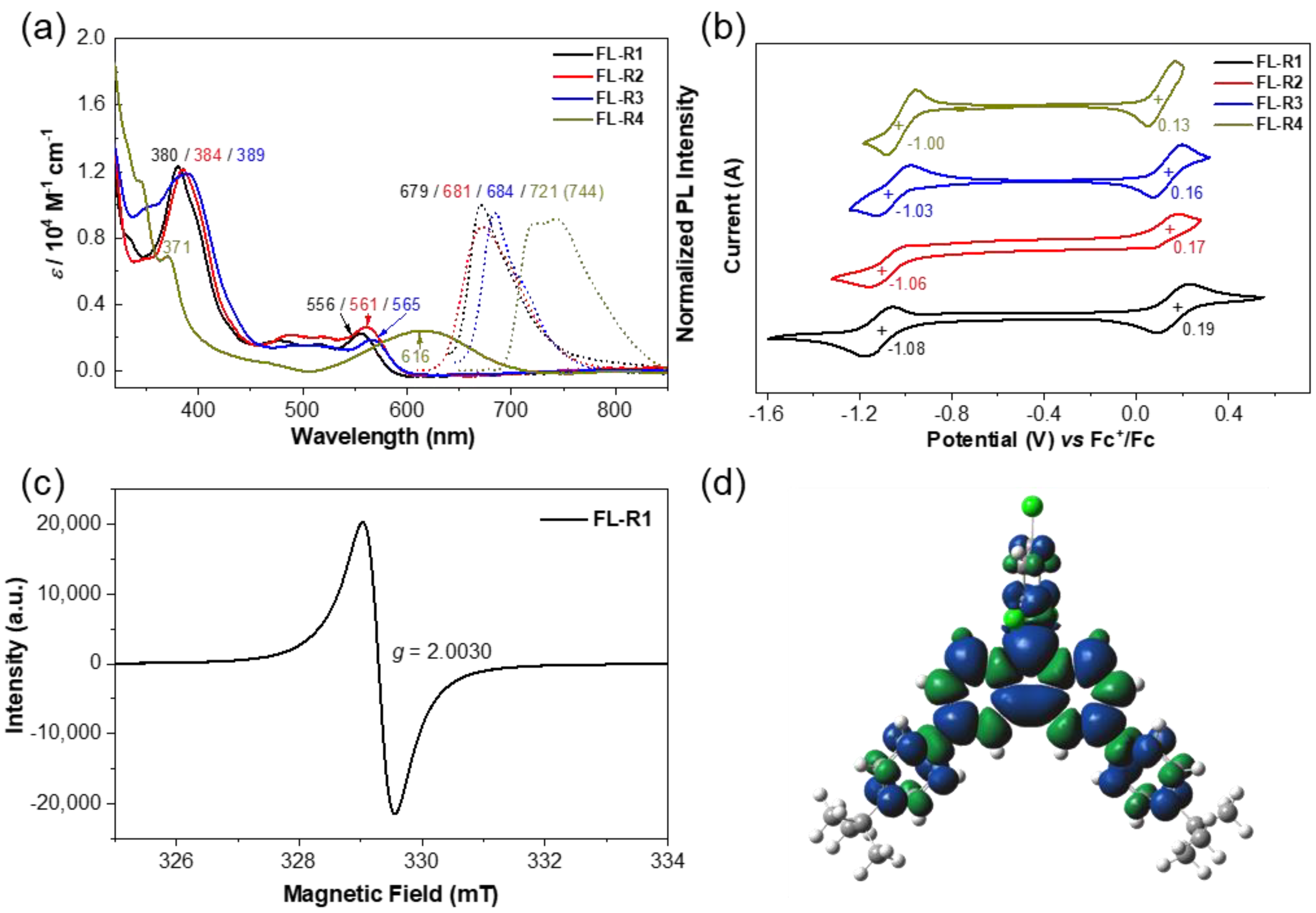

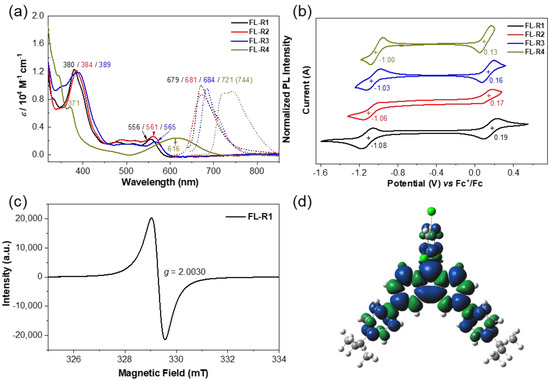

Solutions of the compounds FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 in dichloromethane (DCM) exhibited intense absorption bands at 380, 384, 389, and 371 nm, respectively, in the UV–vis absorption spectra (Figure 2a), which are very different from their respective hydro-precursors 4–7 (Figure S1). Time-dependent (TD)-DFT calculations indicated that these transitions primarily arise from HOMO-1(β) to LUMO(β) and HOMO-2(β) to LUMO(β) electronic transitions (Supporting Information, Figures S2–S8 and Tables S1–S4). Additionally, weak absorption bands corresponding to the lowest-energy transitions were observed at 556 nm (FL-R1), 561 nm (FL-R2), 565 nm (FL-R3), and 616 nm (FL-R4), primarily attributed to the HOMO(β) to LUMO(β) electronic transitions. All fluorenyl radicals exhibited doublet emission with photoluminescence quantum efficiencies (PLQEs) and emission maxima (λem) of 0.8% (679 nm), 0.8% (681 nm), 1.0% (684 nm), and 2.1% (744 nm), respectively (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) UV−vis absorption and normalized fluorescence (FL) spectra of FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 measured in DCM. The excitation wavelengths for FL are 380, 384, 389, and 371 nm, respectively; (b) cyclic voltammograms of FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 measured in DCM (with 0.1 M nBu4N•PF6 as supporting electrolyte, scan rate: 100 mV/s); (c) ESR spectrum of FL-R1 recorded in DCM at room temperature; (d) calculated (UB3LYP/6-31G(d,p)) spin-density distribution map for the FL-R1.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements in DCM showed one reversible oxidation wave and one reversible reduction wave for each radical (Figure 2b). The half-wave potentials for the oxidation/reduction waves were determined to be 0.19/−1.08 V, 0.17/−1.06 V, 0.16/−1.03 V, and 0.13/−1.0 V (vs. Fc⁺/Fc) for FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4, respectively. These results suggest that introducing more electron-rich donating groups (e.g., 4-methoxyphenyl, 3,6-di-tert-butyl-9H-carbazole) raises the HOMO energy level and lowers the LUMO energy level, thereby reducing the electrochemical energy gap. These observations align with theoretical calculations and will be discussed in detail later.

At room temperature (r.t.), FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 displayed well-resolved ESR spectra with g-values of 2.0030, 2.0031, 2.0029, and 2.0029, respectively, consistent with carbon-centered radicals (Figure 2c and Supporting Information, Figures S9–S11). Spin-density maps of the ground-state radicals revealed that the spins are delocalized across the entire π-conjugated backbone (Figure 2d and Supporting Information, Figures S6–S11).

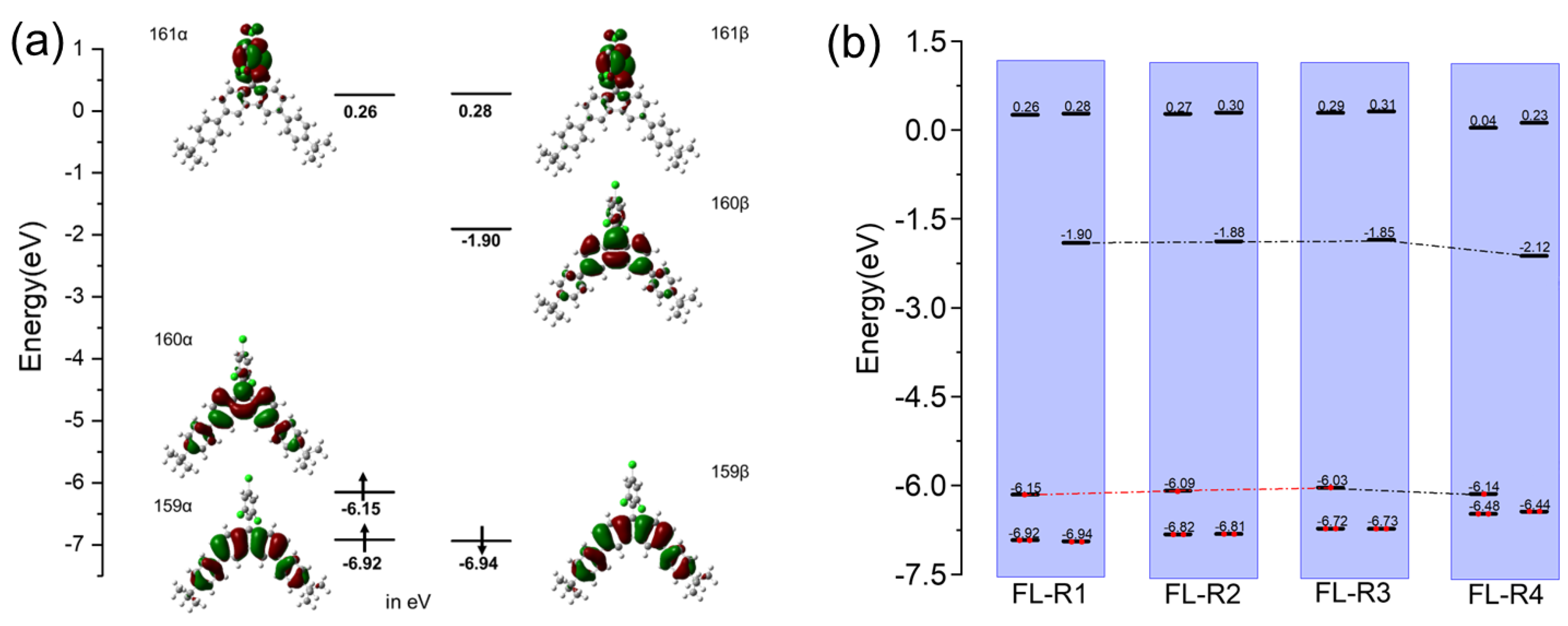

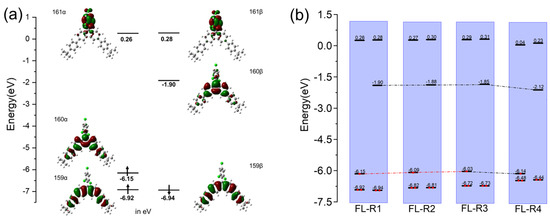

Theoretical calculations were performed to investigate the electronic structures and molecular orbitals of FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 using DFT (UB3LYP/6-31G(d,p)) (Figure 3a and Supporting Information, Figures S2–S4). For FL-R1, the singly occupied molecular orbital (HOMO-α; 160α) shows that the unpaired electron is primarily localized on the central carbon atom of the fluorene unit, with partial extension to the benzene rings of the tert-butylphenyl group. The lowest singly unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO-β; 160β) exhibits a similar electron distribution. MOs 159α and 159β are localized on the central fluorene moiety and the tert-butylphenyl groups. For FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4, their frontier molecular orbital profiles are similar to that of FL-R1. The energy diagrams of these radicals (Figure 3b) clearly show the effect of introducing stronger electron-rich donating groups into the fluorenyl skeleton. Specifically, the HOMO level increases when substituents change from di(4-tert-butylphenyl) to a mixture of 4-tert-butylphenyl and 4-methoxyphenyl, and to di(4-methoxyphenyl). This trend can be explained by the greater electron-donating character of methoxy groups compared to tert-butyl groups. Further substitution with 3,6-di-tert-butyl-9H-carbazole leads to a further decrease in frontier orbital energies, likely due to the high electronegativity of nitrogen atoms in carbazole. The LUMO-β energy decreases more significantly than the HOMO-α, resulting in a smaller band gap, which is also consistent with the observed red shift in the emission spectra.

Figure 3.

(a) The calculated (UB3LYP/6-31G(d,p)) frontier molecular orbital profiles and energy diagram of FL-R1; (b) a summary of the calculated UB3LYP/6-31G(d,p)) energy diagrams of FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4.

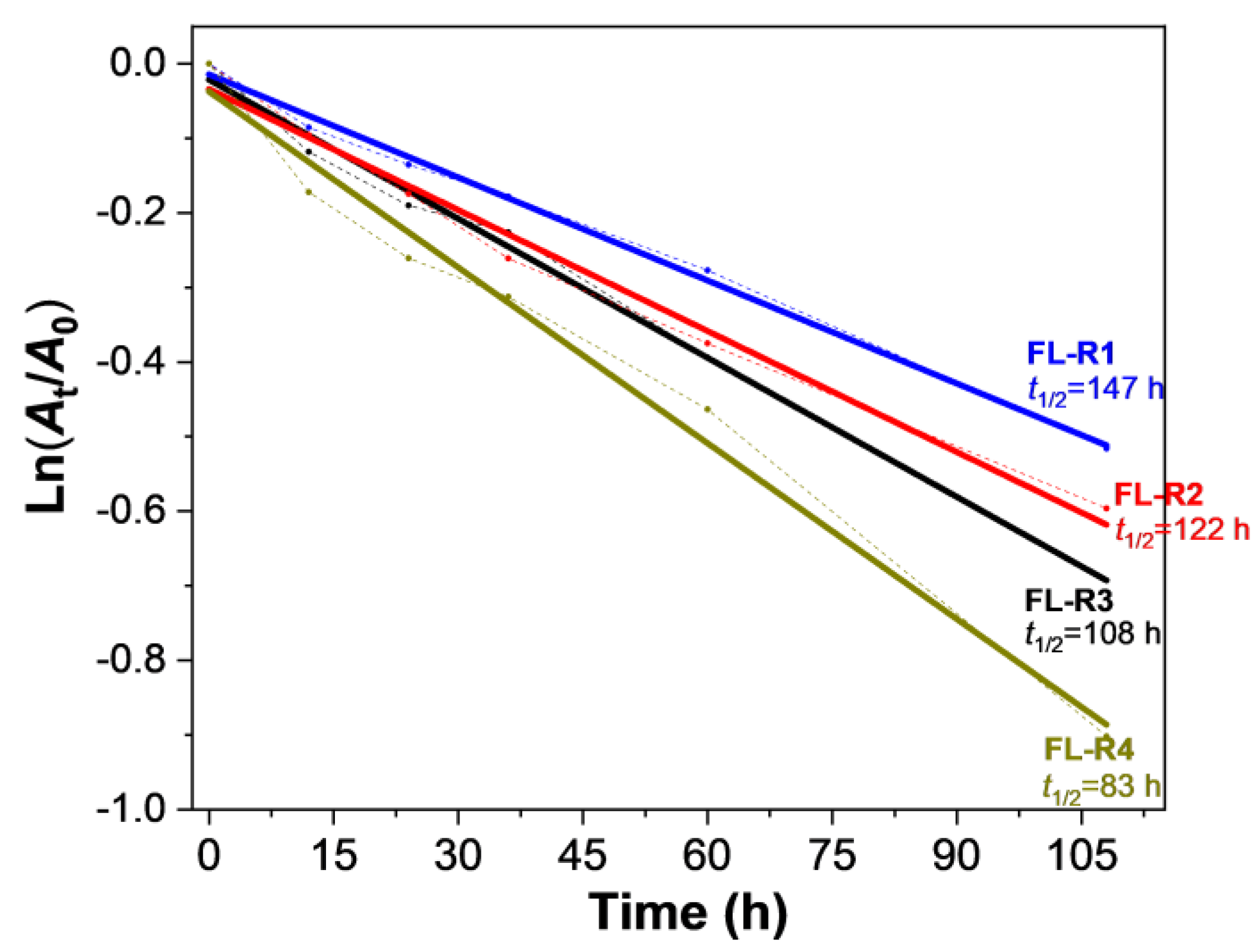

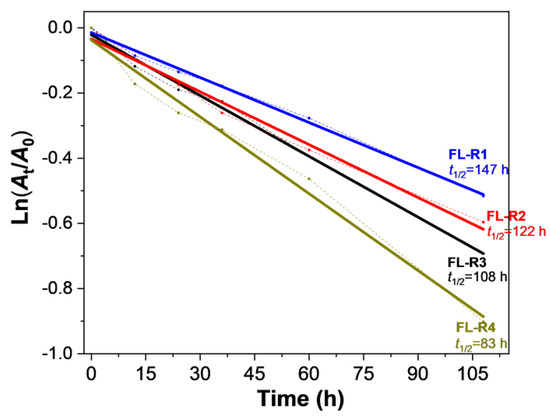

Improving photostability is crucial for luminescent radicals. The decay of absorption intensity for FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 in DCM under ambient conditions and room temperature was investigated to explore how substituent groups with varying electron-donating abilities affect the photostability of these fluorenyl radicals. The estimated half-lives (t1/2) for FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 were 147 h, 122 h, 108 h, and 83 h (Figure 4), respectively, which are longer than other reported monoradicals (see Table S5 in SI). The improvement in photostability can be attributed to efficient spin delocalization, the kinetic blocking of the radical site by the 1,3,5-trichlorophenyl group, and intramolecular donor–acceptor interactions (captodative effect) [38].

Figure 4.

The time-dependent decay of the absorbance at the absorption maximums of FL-R1, FL-R2, FL-R3, and FL-R4 in DCM (1 × 10−4 M) under ambient air and light conditions.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a series of 9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-fluorenyl-based organic luminescent radicals were successfully synthesized and characterized. These radicals represent a new class of organic luminescent materials with tunable doublet emissions in the far-red/NIR region, along with significantly enhanced photostability. Additionally, the impact of various electron-rich donating substituents in the 9-(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)-fluorene radicals on their electrochemical and optical properties and electronic structures was explored and evaluated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemistry7010021/s1, Figures S1–S29 and Tables S1–S5: Additional spectra, structural characterization data, and DFT calculation details. References [21,26,39,40] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

X.H. and J.W. conceived the project. X.H. conducted the synthesis and most physical characterization. T.X., J.Z. and S.W. assisted on the synthesis and theoretical calculations. All authors participated in the paper writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J.W. acknowledges financial support from MOE Tier 2 grants (MOE-T2EP10222-0003 and MOE-T2EP10221-0005) and the A*STAR MTC IRG project (M22K2c0083).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Acknowledgments

X. Hou is grateful for the scholarship support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cui, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Lee, C.-S. Organic Radical Materials in Biomedical Applications: State of The Art and Perspectives. Exploration 2022, 2, 20210264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.X.; Li, Y.; Huang, F. Persistent and Stable Organic Radicals: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. Chem 2021, 7, 288–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratera, I.; Veciana, J. Playing with Organic Radicals as Building Blocks for Functional Molecular Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 303–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guin, J.; De Sarkar, S.; Grimme, S.; Studer, A. Biomimetic Carbene-catalyzed Oxidations of Aldehydes Using TEMPO. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8727–8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, T.; Kawamata, Y.; Maruoka, K. An Organic Thiyl Radical Catalyst for Enantioselective Cyclization. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nooy, A.E.J.; Besemer, A.C.; van Bekkum, H. On the Use of Stable Organic Nitroxyl Radicals for the Oxidation of Primary and Secondary Alcohols. Synthesis 1996, 10, 1153–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Shi, J.; Wei, J.; Yu, T.; Huang, W. Air-Stable Organic Radicals: New-Generation Materials for Flexible Electronics? Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1908015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, X.; Harbuzaru, A.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Changwoo, K.; Guo, H.; Shi, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, H.; et al. Stable Organic Diradicals Based on Fused Quinoidal Oligothiophene Imides with High Electrical Conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4329–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Geng, K.; Li, J.; Wu, S.; Wu, J. Dibenzylidene-s-indacenetetraone Linked n-Type Semiconducting Covalent Organic Framework via Aldol Condensation. ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 4, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, H.; Herng, T.S.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Zeng, W.; Ding, J.; Loh, K.P.; Wee, A.T.S.; Wu, J. Room-Temperature Magnets Based on 1,3,5-Triazine-Linked Porous Organic Radical Frameworks. Chem 2019, 5, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.O.; Gopalakrishna, T.; Phan, H.; Herng, T.S.; Lim, Z.L.; Zeng, Z.; Ding, J.; Kim, D.; et al. Stable 3,6-Linked Fluorenyl Radical Oligomers with Intramolecular Antiferromagnetic Coupling and Polyradical Characters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13048–13058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, J.; Park, J.; Shin, D.; Choi, H.; Seo, J.; Yoo, J.W.; Baek, J. Organic Ferromagnetism: Trapping Spins in the Glassy State of an Organic Network Structure. Chem 2018, 4, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Evans, E.; Dong, S.; Gillett, A.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Hele, T.; Friend, R.; Li, F. Efficient Radical-based Light-emitting Diodes with Doublet Emission. Nature 2018, 563, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahman, A.; Peng, Q.; Ablikim, O.; Ai, X.; Li, F. A Radical Polymer with Efficient Deep-red Luminescence in The Condensed State. Mater. Horiz. 2019, 6, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugg, B.; Krzyaniak, M.; Phelan, B.; Ratner, M.; Young, R.; Wasielewski, M. Photodriven Quantum Teleportation of An Electron Spin State in A Covalent Donor–Acceptor–Radical system. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahman, A.; Hele, T.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, M.; Friend, R.; Li, F.; Evans, E. Understanding The Luminescent Nature of Organic Radicals for Efficient Doublet Emitters and Pure-red Light-emitting Diodes. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, M.; de la Fuente, G. Synthesis and Isolation of A Perchlorotriphenylcarbanion Salt. Tetrahetron Lett. 1970, 11, 4509–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Riera-Figueras, J.; Castaner, J.; Badfa, C.; Monso, J. Inert Carbon Free Radicals. I. Perchlorodiphenylmethyl and Perchlorotriphenylmethyl Radical Series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.A.; Gaillard, E.; Chen, C.C. Photochemistry of Stable Free Radicals: The Photolysis of Perchlorotriphenylmethyl Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 7088–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armet, O.; Veciana, J.; Rovira, C.; Riera, J.; Castaner, J.; Molins, E.; Rius, J.; Miravitlles, C.; Olivella, S.; Brichfeus, J. Inert Carbon Free Radicals. 8. Polychlorotriphenylmethyl Radicals: Synthesis, Structure, and Spin-density Distribution. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 5608–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, V.; Velasco, D.; Latorre, S.; López-Calahorra, F.; Brillas, E.; Juliá, L. [4-(N-Carbazolyl)-2,6-dichlorophenyl]bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl Radical An Efficient Red Light-emitting Paramagnetic Molecule. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 2305–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Obolda, A.; Zhang, M.; Li, F. Organic Light-Emitting Diodes Using a Neutral π Radical as Emitter: The Emission from a Doublet. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 7091–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, W.; Ma, H.; Ma, H.; Obolda, A.; Yan, W.; Dong, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, F. Novel Luminescent Benzimidazole-Substituent Tris(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl Radicals: Photophysics, Stability, and Highly Efficient Red-Orange Electroluminescence. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 6733–6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, F. A Stable Room-Temperature Luminescent Biphenylmethyl Radical. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 2869–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; Abdurahman, A.; Ai, X.; Li, F. Stable Luminescent Radicals and Radical-Based LEDs with Doublet Emission. CCS Chem. 2020, 2, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Kusamoto, T.; Nishihara, H. Luminescence, Stability, and Proton Response of an Open-Shell (3,5-Dichloro-4-pyridyl)bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl Radical. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 44, 11845–11848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, Y.; Kusamoto, T.; Nishihara, H. Enhanced Luminescent Properties of an Open-Shell (3,5-Dichloro-4-pyridyl)bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl Radical by Coordination to Gold. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3731–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Tanushi, A.; Kusamoto, T.; Kochi, S.; Sato, T.; Nishihara, H. A Luminescent Organic Radical With Two Pyridyl Groups: High Photostability and Dual Stimuli-responsive Properties, With Theoretical Analyses of Photophysical Processes. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1996–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Uejima, M.; Ota, W.; Sato, T.; Nishihara, H.; Kusamoto, T. An Open-shell, Luminescent, Two-Dimensional Coordination Polymer with a Honeycomb Lattice and Triangular Organic Radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 4329–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Matsuoka, R.; Kimura, S.; Nishihara, H.; Kusamoto, T. Radical-Based Coordination Polymers as a Platform for Magnetoluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 5610–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Wu, S.; Xu, D.; Tu, L.; Xie, Y.; Pasqués-Gramage, P.; Boj, P.G.; Díaz-García, M.A.; Li, F.; Wu, J.; et al. Stable Xanthene Radicals and Their Heavy Chalcogen Analogues Showing Tunable Doublet Emission from Green to Near-infrared. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202418762. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, M.; Castañer, J.; Riera, J.; Pujadas, J.; Armet, O.; Onrubia, C.; Rio, J.A. Inert Carbon Free Radicals. 5. Perchloro-9-phenylfluorenyl Radical Series. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Castañer, J.; Pujadas, J. Perchloro-9-phenylfluorenyl, A Remarkably Stable Carbon Free Radical. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971, 12, 1699–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahman, A.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, P.; Shen, L.; Peng, Q. A Highly Stable Organic Luminescent Diradical. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202300772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; He, Z.; Ruchlin, C.; Che, Y.; Somers, K.; Perepichka, D.F. Thiele’s Fluorocarbons: Stable Diradicaloids with Efficient Visible-to-Near-Infrared Fluorescence from a Zwitterionic Excited State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15702–15707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Arnold, M.E.; Blinder, R.; Zolg, J.; Wischnat, J.; van Slageren, J.; Jelezko, F.; Kuehne, A.J.C.; von Delius, M.A. A Stable Chichibabin Diradicaloid with Near-Infrared Emission. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202404853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, K.; He, L.; Wang, W.; Lai, W.; Yang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Xie, S.; Yuan, L.; Zeng, Z. Sulfone-Functionalized Chichibabin’s Hydrocarbons: Stable Diradicaloids with Symmetry Breaking Charge Transfer Contributing to NIR Emission beyond 900 nm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 6763–6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehe, H.G.; Janousek, Z.; Merényi, R.; Stella, L. The Captodative Effect. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985, 18, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09; Revision A.2; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Peng, Q.; Chen, X.K.; Guo, Q.; Dong, S.; Evans, E.; Gillett, A.; Ai, X.; Zhang, M.; Credgington, D.; et al. High Stability and Luminescence Efficiency in Donor–acceptor Neutral Radicals Not Following The Aufbau Principle. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).