1. Introduction

Cognitive deficits (in mild cognitive impairment/MCI and dementia) and depression are highly relevant issues in older age: Meta-analysis [

1] estimates of MCI incidence per 1000 person-years between 22.5 (for ages 75–79 years), and 60.1 (for ages 85+ years), the prevalence for all-cause dementia among individuals aged 50 and older is 697 per 10,000 persons [

2]. Depression in old age is also a relevant health problem, with prevalence estimates for major depression in Europe ranging from 9% to 23% [

3]. The differential diagnosis of these three disorders is, therefore, a highly relevant topic in the treatment of older persons, yet there are hardly any studies comparing neuropsychological profiles.

The Geriatric Day Clinic of Nuremberg Hospital is a day-care facility with 45 places where multimorbid older patients are treated. The most frequent main or referral diagnoses relate to internal medicine and orthopedics, such as cardiovascular diseases, gait disorders, dizziness, the tendency of falling, musculoskeletal disorders, and chronic pain. During the standard treatment period of three weeks, each patient receives both individual and group therapies by various therapeutic professions (physiotherapy, ergotherapy, logopedics, psychology) in addition to acute medical and activating nursing treatment as part of an individual therapy plan.

About one third of the patients have a secondary diagnosis of depression, about half of them show cognitive deficits in the context of MCI (10%) or dementia (40%). In total, far more than half of the patients have a secondary diagnosis in the area of psychological disorders (including dementia, depression, anxiety, somatoform disorder), which is why (neuro-) psychological diagnostics and therapy are of particular importance at the day clinic. Patients with a respective diagnosis are treated both individually and in groups by psychologists working in the day clinic, all of whom have a neuro-/geronto-psychological focus of training and activity.

A very frequent issue is, therefore, the differential diagnosis of MCI/dementia/depression by means of a detailed neuropsychological examination and psychological assessment interview. The diagnosis is made in accordance with the ICD-10, which is usually in the medical context, and the current guidelines are always taken into account. According to the S3 guideline Dementia [

4], due to the lack of an exact and universally valid definition, MCI is defined as a syndrome consisting of subjective and objectifiable cognitive impairment with preserved activities of daily living. In particular, amnestic MCI with memory impairment as a major symptom is associated with an increased risk of developing dementia.

2. Methods

Each patient of the clinic was screened at admission with the Mini-Mental-State-Examination (MMSE), clock drawing test and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), some of them were presented for a detailed neuropsychological examination according to medical indication because 1. the presence of cognitive deficits was suspected during medical admission or cognitive screening (MMSE and clock drawing test), or 2. the patient complained of subjective cognitive impairments, or 3. cognitive deficits were observed by the staff during their stay. For the purpose of this paper, all these test profiles from the past five years that met the inclusion criteria (verified diagnosis of MCI, onset or mild dementia, and/or a depressive episode) were systematically analyzed. Since in the differential diagnosis of MCI, depression and dementia, the mild manifestations of dementia are of interest, not advanced dementias, all profiles with an MMSE score below 25 points were excluded to exclude patients with more severely impaired cognition and advanced dementia as much as possible.

The diagnosis of cognitive impairment was made after a detailed neuropsychological examination (NPU) and after cerebral imaging (CT or MRI). Newer methods, such as functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy [

5,

6] have not yet been implemented as a standard at the clinic. Furthermore, detailed blood analysis was performed as part of the exclusion diagnosis, and the ICD dementia criterion of impairments relevant to daily living was operationalized on the basis of a behavioral observation during the stay in the day clinic. In addition to the screenings MMSE, clock drawing test and GDS performed in the admission assessment, the following test procedures were applied during the neuropsychological examination: SKT, NAI maze test, WAIS similarities, RBMT story immediate and delayed.

About the individual test procedures:

2.1. Mini-Mental-State-Examination (MMSE)

The MMSE, developed by Folstein et al. [

7], is one of the most widely used screening instruments for cognitive disorders [

8]. Despite justified criticism regarding its sensitivity, it is used in the early detection of dementia, both in clinical contexts and for research purposes, e.g., for monitoring the course of cognitive disorders or in epidemiological studies. Based on 30 items, the domains of orientation, memory, calculation and attention, language and visual construction are tested. There are differing specifications for the cut-off values, but a cut-off of 25 points is still the most commonly used.

2.2. Clock Drawing Test

The clock drawing test as a cognitive screening method has been systematically investigated since 1983. By now, there are various evaluation systems with regard to the scoring. The modified evaluation according to Shulman [

9] based on a six-point rating scale is widely used, as its sensitivity is considered to be high. However, the instrument does not seem to be very suitable for early detection [

10].

2.3. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

The GDS [

11] was developed as a self-report scale specifically for the assessment of depression in older adults. The original version consists of 30 items (to be answered with either yes or no), but there are now shorter versions containing only 15 or fewer items. The GDS-15 is widely used in geriatrics, including the Nuremberg Hospital. The scale ranges from 0 to 15 points, with a score of more than 5 points indicating the presence of depression. The questionnaire can be completed in about 5 min and is, therefore, ideal for geriatric patients. The 15 items were selected from the long version because they were highly correlated with depressive symptoms in validation studies [

12].

2.4. Syndrom-Kurz-Test (SKT)

The SKT according to Erzigkeit [

13] and Stemmler et al. [

14] assesses memory and attention deficits with nine subtests. In the memory subtests, pictures are presented and the number of objects not remembered is assessed under three conditions (immediately, after delay, recognition). As part of the subtests which measure attention, various tasks must be completed within a time limit of 60 s, whereby the processing time is the relevant variable for assessing attentional performance. Using the new norming [

9], the well-established test is particularly suitable for the early detection of cognitive deficits.

2.5. Nuremberg Aging Inventory (NAI)-Maze Test

Maze tests have been used for decades in various forms and contexts, including assessment of learning behavior, cognitive speed, and visuomotor skills. In the context of neuropsychological testing, the template from the Nuremberg Aging Inventory [

15] is used because it is most appropriate for geriatric patients in terms of size and complexity, and appropriate norming scores are available. The task is to find the way from the center of a maze to its exit as fast as possible using a pencil. The test score is the recorded time taken to complete the task.

2.6. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)-Similarities

The Similarities subtest from the Hamburg–Wechsler Intelligence Test for Adults (WAIS-IV; [

16]) provides information about the logical structure of thought processes and the general (but especially linguistic) capacity for abstraction. The task is to describe how two words or concepts are similar and to articulate the association between each of 16 given pairs of words in the sense of a superordinate term.

2.7. Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test (RBMT)

The Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test [

17] serves as a clinical tool for assessing everyday memory problems. In the Story subtest (with immediate and delayed recall), the subject is asked to listen to a short text and then immediately reproduce as much of the information as possible. About 15 min later, the subject is asked to recall the story he/she heard earlier.

The test procedures used in the neuropsychological examination (NPE) were selected on the basis of various considerations and have been administered by the first author in a clinical setting for many years, particularly in the context of the early detection of cognitive impairment. The use of a test battery (such as the CERAD) was deliberately avoided. In contrast to available test batteries, the composition of the named subtests allows areas, such as logical thinking, planning, and the ability to remember complex linguistic content (and not just individual pieces of information, as is done with common word lists or pictures) to be assessed in a time-efficient manner.

The diagnosis of depressive disorder was made on the basis of a clinical interview covering all ICD-10 depression diagnostic criteria.

Based on the verified diagnoses, patients were divided into four groups:

Analyses of variance (Independent Variable IV: diagnosis group, Dependent Variable DV: cognitive functioning) were calculated and posthoc comparisons were performed to show differences in neuropsychological profiles.

3. Results

A total of 334 test profiles were included in the sample, with small differences in the number of patients for the individual test procedures, since not all procedures could be performed as intended for every patient (for example, due to motor limitation, visual or hearing impairment).

The average age of the patients was 81 years (SD 5.2, min 61, max 93 years), 68% of the patients were female. The patients were distributed among the individual diagnostic groups as follows (

Table 1):

Of the 101 patients with depression, 63 patients (62%) were also cognitively impaired (14 patients had a diagnosis of MCI and 49 suffered from dementia); due to the unequal group sizes these were combined into the cognitively impaired (MCI or dementia) and depression group for the calculations, resulting in the following distribution (

Table 2):

These four groups were then subjected to a more detailed analysis to identify differences and distinctive features in the neuropsychological test profile. For this purpose, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed for both the screenings and the detailed neuropsychological examination with the defined diagnostic groups as independent variables (IV) and the test procedures as dependent variables (DV). In addition, posthoc tests (Bonferroni or Games–Howell) were performed.

3.1. Screenings (MMSE, Clock Drawing Test, GDS)

Multivariate analysis of variance revealed a highly significant difference between diagnostic groups for screening procedures as dependent variables, F(9791) = 16.932,

p < 0.001, partial eta-square 0.133, Wilk’s lambda = 0.651 (

Table 3). Post hoc univariate analyses of variance revealed a statistically significant difference between diagnostic groups for not only MMSE but also clock drawing test and GDS.

For each dependent variable, a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction was performed posthoc.

The MMSE showed a statistically significant differences between the “dementia” group and the “MCI” group, p = 0.022 (Mdiff = −0.83, 95%-CI [−1.58, −0.08]) and between “dementia” and “depression”, p = 0.001 (Mdiff = −1.37, 95%-CI [−2.33, −0.40]), but not between “dementia” and “cognitively impaired AND depression”, p = 1.0 (Mdiff = −0.38, 95%-CI [−1.17, 0.40]). There was also no significant difference between “MCI” and “depression”, p = 1.0 (Mdiff = −0.54, 95%-CI [−1.61, 0.53]), nor between “MCI” and “cognitively impaired AND depression”, p = 1. 0 (Mdiff = 0.44, 95%-CI [−0.47, 1.36]) nor between “depression” and “cognitively impaired AND depression”, p = 0.108 (Mdiff = 0.98, 95%-CI [−0.11, 2.08]).

There was no significant difference in the clock drawing test for any group comparison: “dementia” and “MCI”, p = 0.453 (Mdiff = 0.29, 95%-CI [−0.14, 0.71]; “dementia” and “depression”, p = 1.0 (Mdiff = 0.25, 95%-CI [−0.29, 0.80]); “dementia” and “cognitively impaired AND depression”, p = 1.0 (Mdiff = −0.22, 95%-CI [−0.67, −0.22]), “MCI” and “depression”, p = 1.0 (Mdiff = −0.03, 95%-CI [−0.64, 0.57]); “MCI” and “cognitively impaired AND depression”, p = 0.056 (Mdiff = −0.51, 95%-CI [−1.02, 0.01]), “depression” and “cognitively impaired AND depression”, p = 0.255 (Mdiff = 0.47, 95%-CI [−0.14, 1.09]).

In GDS, the group of patients with depression differed significantly from “dementia”, p < 0.001 (Mdiff = 4.48, 95%-CI [3.1, 5.86]) as well as from “MCI”, p < 0.001 (Mdiff = 4.76, 95%-CI [3.23, 6.29]), but not from “cognitively impaired AND depression”, p = 0.495 (Mdiff = 1.03, 95%-CI [−0.54, 2.59]).

3.2. Neuropsychological Examination (NPE)

Multivariate analysis of variance revealed a highly significant difference between diagnostic groups for the tests of the detailed NPE as dependent variables, F(21,833) = 11.237,

p < 0.001, partial eta-square 0.212, Wilk’s Lambda = 0.489 (

Table 4).

Posthoc univariate analyses of variance showed a statistically significant difference between diagnostic groups for all psychometric tests.

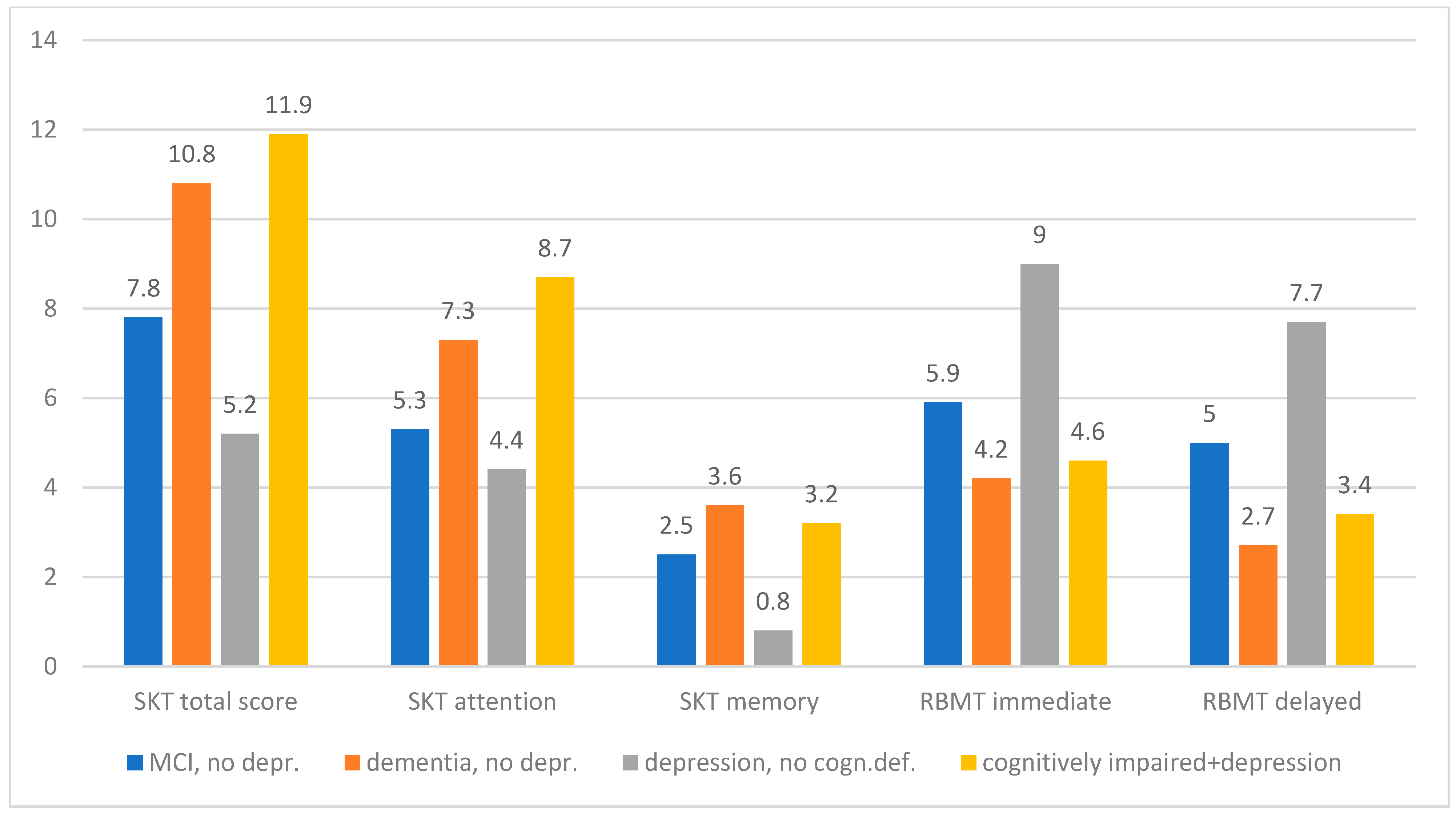

Graphically, the differences between the diagnosis groups in the individual test procedures present themselves as follows (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2):

Posthoc, a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (for variance homogeneity) or Games–Howell (for variance inhomogeneity) was performed for each dependent variable (detailed statistical values can be found in the

supplement).

3.3. SKT

Regarding the SKT total score, dementia was significantly differentiated from MCI and depression, but not from “cognitively impaired and depression”. MCI was also significantly distinguished from depression and “cognitively impaired and depression”. Patients with depression were significantly different from “cognitively impaired and depression”.

In the memory subscore, there were significant differences between dementia and MCI as well as between dementia and depression, but dementia could not be distinguished from “cognitively impaired and depression”. MCI was significantly different from depression but not from “cognitively impaired and depression”. Patients with depression significantly differed from “cognitively impaired and depression”.

In the attention subscore, dementia was significantly different from MCI as well as from depression and from “cognitively impaired and depression”. MCI differed from “cognitively impaired and depression”, but not from depression. Patients with depression showed a significant difference from “cognitively impaired and depression”.

3.4. RBMT

In the story immediate recall subtest there were significant differences between dementia and MCI as well as between dementia and depression, but dementia could not be distinguished from “cognitively impaired and depression”. MCI differed significantly from depression and from “cognitively impaired and depression”. Depression could also be distinguished from “cognitively impaired and depression”.

In the story delayed recall subtest, analogous results were obtained, i.e., significant differences between dementia-MCI, dementia-depression, MCI-depression, MCI-“cognitively impaired and depression” and depression-” cognitively impaired and depression”. No significant differences were found between dementia and “cognitively impaired and depression”.

3.5. NAI Maze Test

There were significant differences between dementia and MCI as well as depression, but dementia could not be distinguished from “cognitively impaired and depression”. MCI was different from “cognitively impaired and depression” but not from depression. However, depression could be significantly distinguished from “cognitively impaired and depression”.

3.6. WAIS Similarities

Here, a picture analogous to the results in the NAI maze test emerged: there were again significant differences between dementia and MCI as well as depression, but dementia could not be distinguished from “cognitively impaired and depression”. MCI was different from “cognitively impaired and depression” but not from depression. However, depression could be significantly differentiated from “cognitively impaired and depression”.

Hence, the following typical cognitive profiles of the individual diagnostic groups can be derived:

3.7. MCI

Patients with a verified diagnosis of MCI show a mild memory impairment and a very mild attention impairment according to the interpretation guidelines of the SKT. The total score of 7.8 points is interpreted as “Mild cognitive impairment”. In contrast, the standardized profile scores in the RBMT, which are calculated using the raw scores, do not indicate memory impairment yet. The 20.9 points in the WAIS correspond to 9 value points or a percentile rank of 37 and are thus also considered an inconspicuous result. Similarly, the result in the maze test, with a percentile rank of 65–73, can also be considered not suspicious.

3.8. Dementia

Patients with a diagnosis of dementia show a moderate memory impairment and a mild attention impairment in the SKT; according to the manual, the overall score is interpreted as “suspected pathological decline”. The RBMT profile scores indicate borderline findings regarding memory performance, the WAIS score (6 value points, percentile rank 9) is below average. The result in the maze test with a percentile rank of 27–35 is to be considered conspicuous.

3.9. Cognitively Impaired and Depression

In the SKT, patients with cognitive impairment and depressive disorder show a mild memory impairment and a mild attention deficit; the total score corresponds to the “suspected pathological decline”. The profile values in the RBMT speak of a borderline finding regarding memory performance. The WAIS score (6-point values, percentile rank 9) is below average. The result in the maze test with a percentile rank of 27–35 is considered conspicuous.

3.10. Depression

Depressed patients show no memory impairment as well as a very mild attention impairment in the SKT, but the total score is classified as “mild cognitive impairment.” However, the profile can only be interpreted to a limited extent due to the inhomogeneity of subscore profiles. The profile scores in the RBMT suggest normal findings regarding memory performance, the WAIS score (11 value points, percentile rank 63) is average. The result in the maze test with a percentile rank of 65–73 can also be considered inconspicuous.

The graphical representation of the individual diagnostic groups (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) shows the following characteristics:

4. Discussion

In clinical diagnostics, it is of particular importance to detect dementia at an early stage and, in particular, to distinguish it from depression, especially since the two conditions are treated in a different way. Misdiagnosis in the sense of undetected dementia, because cognitive deficits are erroneously interpreted as an expression of depression, has the consequence that an early anti-dementia treatment as well as further measures indicated in the case of dementia, such as precautionary measures, etc., may be omitted.

Conversely, an erroneous diagnosis of dementia in the presence of cognitive deficits that occur in the context of depression may also lead to negative consequences in the form of overtreatment or additional psychological stress for patients and their relatives who are confronted with a dementia diagnosis that may turn out to be incorrect after treatment of the depressive symptoms. In this respect, the question is highly relevant whether and, if so, which screening and further psychological testing procedures can differentiate between dementia and depression.

Commonly used screenings, such as MMS and clock drawing tests are insufficient for differential diagnosis of dementia, MCI, and depression, a detailed NPE is absolutely required.

The results show that the MMSE in contrast to the clock drawing test can significantly differentiate between dementia and depression: Patients with dementia have a lower score. This is all the more remarkable as only test profiles with an MMSE score of 25 points or more were included in the sample. With exception of the maze test, the test procedures used in the neuropsychological examination (SKT, RBMT, WAIS) also significantly distinguish between the two diseases. Both attention performance and memory function in the SKT are poorer in dementia patients than in depressive patients, as is memory performance for complex content (RBMT) and logical structure of thought processes and the general capacity for abstraction (WAIS).

The distinction between MCI and depression is even more challenging, as the cognitive impairment in MCI is often less pronounced than in dementia. The diagnosis of MCI is usually accompanied by the recommendation of annual follow-up examinations, as the risk of developing dementia is increased, but drug therapy is not indicated according to official guidelines. The screening methods MMSE and clock drawing test do not differentiate MCI from depression; in the NPE, the SKT total score (but only due to the memory subscore) and the RBMT proved to be suitable to significantly differentiate MCI from depression. Patients with MCI showed poorer memory performance, but no relevant differences to depressive patients were found with regard to attention performance.

Irrespective of the presence of depression, the differentiation of MCI from onset dementia is also an important aspect since the possibility of anti-dementia treatment is only given with a manifest dementia diagnosis, whereas MCI requires regular progress monitoring in order to detect conversion to dementia (up to 10% annually). Here, all test procedures from the NPE, as well as the MMSE, proved to be suitable to significantly differentiate between both diagnostic groups.

Furthermore, it is very common to find hybrid patterns in clinical practice: Many patients with cognitive impairment in the sense of MCI or onset dementia also exhibit symptoms that justify the diagnosis of a depressive episode. In this case, it is a major challenge to identify the existing cognitive impairment as MCI or dementia and to differentiate it from pure depression. All test procedures of the NPE proved to be suitable for differentiating these two groups; patients with MCI or dementia in the presence of concomitant depression performed more poorly in all areas than patients with depression alone. In the screening procedures, however, no significant differences were found between the two groups.

In summary, patients with depression, in contrast to patients with MCI or dementia, generally do not show memory impairment in neuropsychological testing; their attentional performance is comparable to that of MCI patients. The logical structure of thought processes and the general capacity for abstraction are unimpaired in patients with depression as well as in the presence of MCI. As soon as abnormalities in memory performance occur, it must be assumed that depression is not the only cause, but that MCI in the sense of a prodromal stage of dementia is likely to be present. As soon as the logical structure of thought processes and the general capacity for abstraction are impaired, a demential development must be considered, as well as in the case of conspicuous values in the maze test. Attention showed to be impaired in all diagnostic groups, only its degree of impairment can be used as an indicator for a differential diagnosis.

Furthermore, it should be taken into account that in addition to the results of screening procedures and the neuropsychological examination, the clinical and diagnostic training and experience of the examiner are of great importance. They enable the identification of specific conspicuous symptoms which are not necessarily reflected in the results of a test but may provide indicators of a pathological brain-organic process with a corresponding recommendation for follow-up even without a manifest diagnosis (e.g., word finding disturbances, confabulations, etc.). In combination with the presented components of the NPE, it should be possible to detect brain-organic cognitive deficits at an early stage and to distinguish them from depressive disorders. Comparable studies are predominantly concerned with the differential diagnosis of dementia and depression (e.g., [

18,

19,

20,

21]). Although in most cases other neuropsychological test procedures were used, the results show that a differential diagnosis is possible, since patients with dementia usually show lower scores in the NPE (perception, attention/memory, calculation, and language functions). The differential diagnosis is supported by radiological examinations, which, for example, particularly consider the hippocampal volume. As a limitation of the study, the retrospective analysis of neuropsychological profiles that emerged in the clinical context should be mentioned in particular. Therefore, it is not a controlled study in which patients with dementia, MCI, and depression were systematically examined. In addition, there is the selectivity of the sample, as it is the specific clientele of a geriatric day hospital. Nevertheless, the results seem relevant to us, especially for clinical practice. Furthermore, our statement only applies to the psychometric test procedures presented above. There are numerous other procedures and test batteries available in neuropsychology for assessing cognitive functions. Although each neuropsychological examination should yield the same result even if different procedures are used, it is up to the respective examiner to select tests that are not only suitable for the particular question, but also take into account the context (in-or outpatients, study, etc.) and specific features of the subject (age, motor or sensory limitations, etc.).