“It’s Not a One-Time Conversation”: Australian Parental Views on Supporting Young People in Relation to Pornography Exposure

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Age of First Exposure

1.2. Potential Impact of Pornography Viewing at a Young Age

1.3. Parental Awareness and Responses to Pornography

1.4. Parental Communication about Pornography

1.5. Educational Support about Pornography Usage

1.6. Gaps in the Literature

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Data Analysis

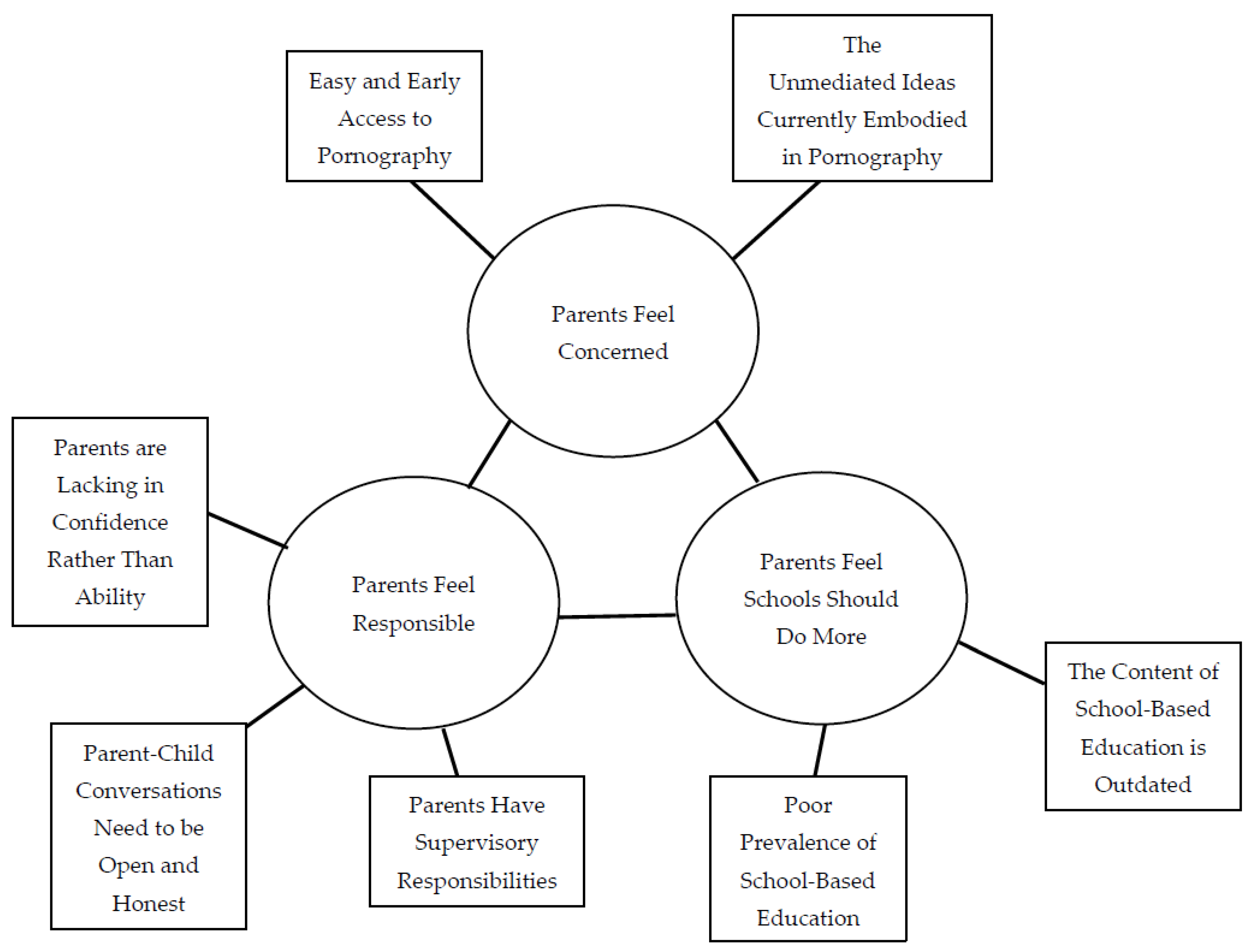

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Theme One: Parents Feel Concerned

3.1.1. Easy and Early Access to Pornography

I know they have access, you know they’re on the devices now, you know, a lot of the time. Because school is all devices as well. So, they have access, “legal access”, as well as you know personal access to devices.

…through their access to the internet, I guess. So, they have more access to this pornography. And there’s also just more of it out there as well. So, they’re more likely to come across it.

I guess the thing is, I don’t, I don’t know how much of a problem it is, maybe because my kids are really young. So I guess because I can’t see the problem, I don’t really know what is there to fix. So, I am like literally head in the clouds of this stuff like where I just feel like lah-lah-lah-lah-lah.

…In my house, we have a laptop, and both me and my partner have phones, but we have no iPad and the kids don’t have any of their own devices. And sometimes I think that we’ve been very lucky to just kind of not have to engage with that… I think my kids access to it is quite limited.

3.1.2. The Unmediated Ideas Currently Embodied in Pornography

Reality and Fantasy

So over here you’ve got the bubble of, you know, this is a loving, intimate relationship, you know, it’s respectful, it’s caring, it’s nurturing, it’s fun, its kind, you know, and this is real. And then you’ve got, over here, you’ve got porn, which is like not real.

Negative and Positive Pornography

So you don’t want these 15 year old boys thinking that’s how you treat women…It’s not what you do to a 15 year old girl…That kind of an education, [it’s] alright if you want to…get excited about but it’s not actually how you respect women.

3.2. Theme Two: Parents Feel Responsible

It’s going to be a matter of looking at my son, working out where he is at, if he’s starting to get interest, if he’s on YouTube, if he’s asking questions about porn, then that’s the time that you have to follow your children’s lead.

3.2.1. Parent–Child Conversations Need to Be Open and Honest

I think the pornography part is still the taboo part…we’ve come a long way in being more open about talking about sex… But I think that…pornography in itself is probably something that’s still not talked about, people don’t admit to watching it.(Jess)

Every single moment is a teachable moment. You know, so like if a song comes on the radio and it’s talking about slapping my bitch whatever, I don’t know, maybe that’s a teachable moment. Like what is this person trying to say...everything is a teachable moment if you just put it in the right context.(Nancy)

3.2.2. Parents Have Supervisory Responsibilities

So to ignore that or pretend it doesn’t happen seems very blinkered… It would be like not talking about drinking in health education, everybody drinks, but oh gosh we can’t talk about drinking, its dumb. If everyone is having sex and everyone’s watching porn then of course we would have to talk about it.(James)

You can’t pretend it doesn’t exist. It’s there, it’s here. It might not be everyone’s ideal, but, children, if they don’t hear it from you, they go find it out for themselves.(Elizabeth)

3.2.3. Parents Are Lacking in Confidence Rather Than an Ability

3.3. Theme Three: Parents Feel Schools Should Do More

3.3.1. Poor Prevalence of School-Based Education

I think that… teenagers don’t like what their parents have to tell them... So even if it misses out a bit at home at least there is some capture at school… I think it should be part of the sex education process. Like I think that’s a good home for it to kind of sit in between the sex education and the cyber and the internet and the internet education.

3.3.2. The Content of School-Based Education Is Insufficient and Outdated

I asked a question whether the boys and girls were separated. And I think they might have been at some point, which, again, is something… that’s just crazy that just speaks to the very old understandings of gender and sexuality and all that sort of stuff. [I am also] not sure about the information that they’re getting, and the kids are not engaged… It’s just something that they have to sit through. So, in that sense, they’re not necessarily successful, I think.

The idea of disengaging content is also taken up by Paul:

I feel like we do quite good reproduction education and even not bad education about sexually transmitted infections, for example… But I think there’s just an enormous gaping chasm in spaces for young people to talk about sexuality as opposed to sort of reproduction or safety.

I feel like there’s sort of nothing in between, there’s either that, which is engaging, but for terrible reasons and I think ways that can be quite harmful, and then what we do around sexuality is so dry, so oriented towards this idea of sex equals danger as opposed to sex equals pleasure. That’s almost totally disconnected from the experience of young people exploring their sexuality.

I didn’t know I was kind of not sure how much to give them how much to hold back and so I think being guided by the different sessions that the school would hold, and you being a part of that just helped, and you were kind of like okay, that’s enough for now because you kind of went yeah that’s probably all they need to know at this age.

3.4. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grattan, M. Internet is Parents Worst Nightmare. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/internet-is-parents-worst-nightmare-20121117-29iql.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household Use of Information Technology. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/technology-and-innovation/household-use-information-technology/latest-release#:~:text=People%20aged%2015%20to%2017,and%20banking%20(all%2080%25) (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Braun-Courville, D.K.; Rojas, M. Exposure to Sexually Explicit Web Sites and Adolescent Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flood, M.; Hamilton, C. Regulating Youth Access to Pornography; The Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, M.; Hamilton, C. Youth and Pornography in Australia: Evidence on the Extent of Exposure and Likely Effects; The Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.; Brady, D.; Olafsson, K.; Hartley, J.; Lumby, C. Risks and Safety for Australian Children on the Internet: Full Findings from the AU Kids Online Survey of 9–16 Year Olds and their Parents. Cult. Sci. 2011, 4, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, L. Teenage Sex Offences Increase, Australian Bureau of Statistics Figures Show. Available online: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/teenage-sex-offences-increase-australian-bureau-of-statistics-figures-show/news-story/787e74808cc07b998ad98b99cac3cf63 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.M. Adolescents and Pornography: A Review of 20 Years of Research. J. Sex Res. 2016, 53, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Mitchell, K.J. Exposure to Internet pornography among children and adolescents: A national survey. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2005, 8, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.-S.; Leung, M.; Chen, C.-H.; Yang, S.C. Exposure to Internet Pornography Amoung Taiwanese Adolescents. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2013, 41, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netsafe; UK Safer Internet Centre; Plymouth Univerity; Office of the eSafety Commissioner. Parenting and Pornography: Findings from Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom: Summary Report; Office of the eSafety Commissioner: Pyrmont, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Healy-Cullen, S.; Taylor, J.E.; Ross, K.; Morison, T. Youth Encounters with Internet Pornography: A Survey of Youth, Caregiver, and Educator Perspectives. Sex. Cult. 2022, 26, 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassó, A.M.; Bruch-Granados, A. Psychological and Forensic Challenges Regarding Youth Consumption of Pornography: A Narrative Review. Adolescents 2021, 1, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.; Yes, Your Child Will Be Exposed to Online Porn. But Don’t Panic—Here’s What to do Instead. Available online: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/insight/article/yes-your-child-will-be-exposed-to-online-porn-but-dont-panic-heres-what-to-do-instead/9usz8p3g7 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Lim, M.S.C.; Agius, P.A.; Carrotte, E.R.; Vella, A.M.; Hellard, M.E. Young Australians’ Use of Pornography and Associations with Sexual Risk Behaviours. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.H.; Smith, E.; Davies, C. Responsibilities, Tensions and Ways Forward: Parents’ Perspectives on Children’s Sexuality Education. Sex Educ. 2017, 17, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, E.E.; Ortiz, R.R.; White, S.R. Emerging Adults’ Responses to Active Mediation of Pornography During Adolescence. J. Child. Media 2015, 9, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, N.; Steele, V.R.; Staley, C.; Sabatinelli, D.; Hajcak, G. Modulation of Late Potentials by Sexual Images in Problem Users and Controls Inconsistent with “Porn Addiction”. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 109, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karila, L.; Wéry, A.; Weinstein, A.; Cottencin, O.; Petit, A.; Reynaud, M.; Billieux, J. Sexual Addiction or Hypersexual Disorder: Different Terms for the Same Problem? A Review of Literature. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4012–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, E.; Behun, R.; Manning, J.; Reid, R. The Impact of Internet Pornography on Adolescents: A Review of the Research. Sex. Addict. Compulsivity 2012, 19, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, E.A.; Morris, G.; Wesche, R.; Edwards, K.M.; Banyard, V.L. Prospective Associations Between Pornography Viewing and Sexual Aggression Among Adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2022, 32, 1612–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Mitchell, K.J.; Hamburger, M.; Diener-West, M.; Leaf, P.J. X-rated Material and Perpetration of Sexually Aggressive Behavior Among Children and Adolescents: Is There a Link? Aggress. Behav. 2011, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonino, S.; Ciairano, S.; Rabaglietti, E.; Cattelino, E. Use of Pornography and Self-reported Engagement in Sexual Violence Among Adolescents. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 3, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, N.; Larkins, C.; Barter, C.; Wood, M.; Aghtaie, N.; Lanau, A.; Överlien, C. Pornography, Sexual Coercion and Abuse and Sexting in Young People’s Intimate Relationships: A European Study. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 2919–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornor, G. Child and Adolescent Pornography Exposure. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2020, 34, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadara, A.; El-Murr, A.; Latham, J.; Australian Institute of Family Studies; Department of Social Services, Australian Government. Online Pornography: Effects on Children and Young People: Research Snapshot; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, Australia, 2017.

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.M. Adolescents’ Exposure to Sexually Explicit Online Material and Recreational Attitudes Toward Sex. J. Commun. 2006, 56, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.E. Online Pornography—Should Schools be Teaching Young People about the Risks? An Exploration of the Views of Young People and Teaching Professionals. Sex Educ. 2016, 16, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.C.; Carrotte, E.R.; Hellard, M.E.; Lim, M.S.C. What Behaviors Do Young Heterosexual Australians See in Pornography? A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.M. Adolescents’ Exposure to Sexually Explicit Internet Material and Notions of Women as Sex Objects: Assessing Causality and Underlying Processes. J. Commun. 2009, 59, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M. Pornography Has Deeply Troubling Effects on Young People, but There Are Ways We Can Minimise the Harm. Available online: https://theconversation.com/pornography-has-deeply-troubling-effects-on-young-people-but-there-are-ways-we-can-minimise-the-harm-127319#:~:text=Some%20impacts%20are%20deeply%20troubling%2C%20particularly%20pornography’s%20contribution%20to%20sexual%20violence.&text=But%20with%20sexually%20explicit%20material,to%20developing%20more%20ethical%20porn (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Guy, R.J.; Kaldor, J.M.; Patton, G.C. Internet Pornography and Adolescent Health: Early Findings on Effects of Online Pornography on Adolescents show Associations with Risky Behaviour. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 196, 546–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, F.; Smith, C.; Barker, M. ‘I’m Just Curious and Still Exploring Myself’: Young People and Pornography. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 3738–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLelland, M. ‘Not in front of the parents!’ Young people, sexual literacies and intimate citizenship in the internet age. Sexualities 2017, 20, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurcher, J.D. The Interplay between Peer and Authoritative Injunctive Norms of Parents Discussing Pornography with Adolescents. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2019, 14, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.C.; Wright, C.; Curtis, M.; Hellard, M.E.; Lim, M.S.C.; Temple-Smith, M.J. ‘Not My Child’: Parenting, Pornography, and Views on Education. J. Fam. Stud. 2021, 27, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chang, F.-C.; Chiu, C.-H.; Li, F.; Chen, P.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-P.; Chiang, J.-T. Parent–Child Discrepancies in Reports of Exposure to Violence/Pornography on Mobile Devices and the Impact on Children’s Psychosocial Adjustment. CyberPsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurcher, J.D. Exploring Descriptive Norms of Parent-Child Communication about Pornography Among Parents of Middle-choolers in the US. J. Child. Media 2017, 11, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, E.; Melhuish, N. Children’s Exposure to Sexually Explicit Content: Parents’ Awareness, Attitudes and Actions. SSRN Electron. J. 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, P.; Xu, H.; Rosson, M.B.; Carroll, J.M. Parents Just Don’t Understand: Why Teens Don’t Talk to Parents about Their Online Risk Experiences. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February-1 March 2017; pp. 523–540. [Google Scholar]

- Widman, L.; Javidi, H.; Maheux, A.J.; Evans, R.; Nesi, J.; Choukas-Bradley, S. Sexual Communication in the Digital Age: Adolescent Sexual Communication with Parents and Friends About Sexting, Pornography, and Starting Relationships Online. Sex. Cult. Interdiscip. J. 2021, 25, 2092–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Quiring, O.; Daschmann, G. Peers, Parents and Pornography: Exploring Adolescents’ Exposure to Sexually Explicit Material and Its Developmental Correlates. Sex. Cult. 2012, 16, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pound, P.; Langford, R.; Campbell, R. What do Young People Think About Their School-Based Sex and Relationship Education? A Qualitative Synthesis of Young People’s Views and Experiences. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education and Training. Schools Policy: A Whole School Approach to Tackling Early School Leaving. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/early-school-leaving-group2015-policy-messages_en.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Victorian Department of Education and Training. Whole School Sexuality Education. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/physed/Pages/wslearning.aspx (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Sparks, S.D. Privacy, Porn, and Parents in the Room: Sex Education’s Pandemic Challenges. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/privacy-porn-and-parents-in-the-room-sex-educations-pandemic-challenges/2021/10 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Byrne, D. A Worked Example of Braun and Clarke’s Approach to Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-J.G. Reconsidering Constructivism in Qualitative Research. Educ. Philos. Theory 2012, 44, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. Ontological, Epistemological and Methodological Assumptions: Qualitative versus Quantitative; Online Submission; University of Exeter: Exeter, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N. ‘A Starting Point For Your Journey, Not a Map’: Nikki Hayfield in Conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke about Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2022, 19, 424–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Castleman, M. Dueling Statistics: How Much of the Internet Is Porn? Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/au/blog/all-about-sex/201611/dueling-statistics-how-much-the-internet-is-porn (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Sabina, C.; Wolak, J.; Finkelhor, D. The Nature and Dynamics of Internet Pornography Exposure for Youth. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 691–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostad, W.L.; Gittins-Stone, D.; Huntington, C.; Rizzo, C.J.; Pearlman, D.; Orchowski, L. The Association Between Exposure to Violent Pornography and Teen Dating Violence in Grade 10 High School Students. Arch. Sex. Behav. Off. Publ. Int. Acad. Sex Res. 2019, 48, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boniel-Nissim, M.; Efrati, Y.; Dolev-Cohen, M. Parental Mediation Regarding Children’s Pornography Exposure: The Role of Parenting Style, Protection Motivation and Gender. J. Sex Res. 2020, 57, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabbe, M.; Flood, M. School-Based Education to Address Pornography’s Influence on Young People: A Proposed Practice Framework. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2021, 16, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants (Pseudonyms) | Gender | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | ||

| Elizabeth | Female | Male | 6 |

| Paul | Male | Male | 17 |

| Male | 19 | ||

| Sharron | Female | Male | 13 |

| Male | 15 | ||

| Female | 17 | ||

| Julie | Female | Female | 10 |

| Male | 12 | ||

| Naomi | Female | Female | 5 |

| Male | 8 | ||

| James | Male | Male | 15 |

| Male | 17 | ||

| Female | 20 | ||

| Nancy | Female | Male | 7 |

| Female | 10 | ||

| Jess | Female | Male | 7 |

| Male | 11 | ||

| Male | 14 | ||

| Total | F = 6 | F = 5 | F mean age = 12.4 |

| M = 2 | M = 13 | M mean age = 12.4 |

| Question Number | Question | Question Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Question 1 | What have you heard or read about pornography use by young people? |

|

| Question 2 | What conversations do you think parents should be having with their children about pornography? |

|

| Question 3 | What age do you think children should be educated about pornography use? |

|

| Question 4 | Who do you think should be educating young people about pornography use? Why? |

|

| Question 5 | Do you think education about pornography should be a part of the health education taught in schools? |

|

| Question 6 | Is there anything else you’d like to tell me about pornography use by young people? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burke, S.; Purvis, M.; Sandiford, C.; Klettke, B. “It’s Not a One-Time Conversation”: Australian Parental Views on Supporting Young People in Relation to Pornography Exposure. Psych 2023, 5, 508-525. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych5020034

Burke S, Purvis M, Sandiford C, Klettke B. “It’s Not a One-Time Conversation”: Australian Parental Views on Supporting Young People in Relation to Pornography Exposure. Psych. 2023; 5(2):508-525. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych5020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurke, Sally, Mayumi Purvis, Carol Sandiford, and Bianca Klettke. 2023. "“It’s Not a One-Time Conversation”: Australian Parental Views on Supporting Young People in Relation to Pornography Exposure" Psych 5, no. 2: 508-525. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych5020034

APA StyleBurke, S., Purvis, M., Sandiford, C., & Klettke, B. (2023). “It’s Not a One-Time Conversation”: Australian Parental Views on Supporting Young People in Relation to Pornography Exposure. Psych, 5(2), 508-525. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych5020034