Freezing Effect and Bystander Effect: Overlaps and Differences

Abstract

1. Introduction

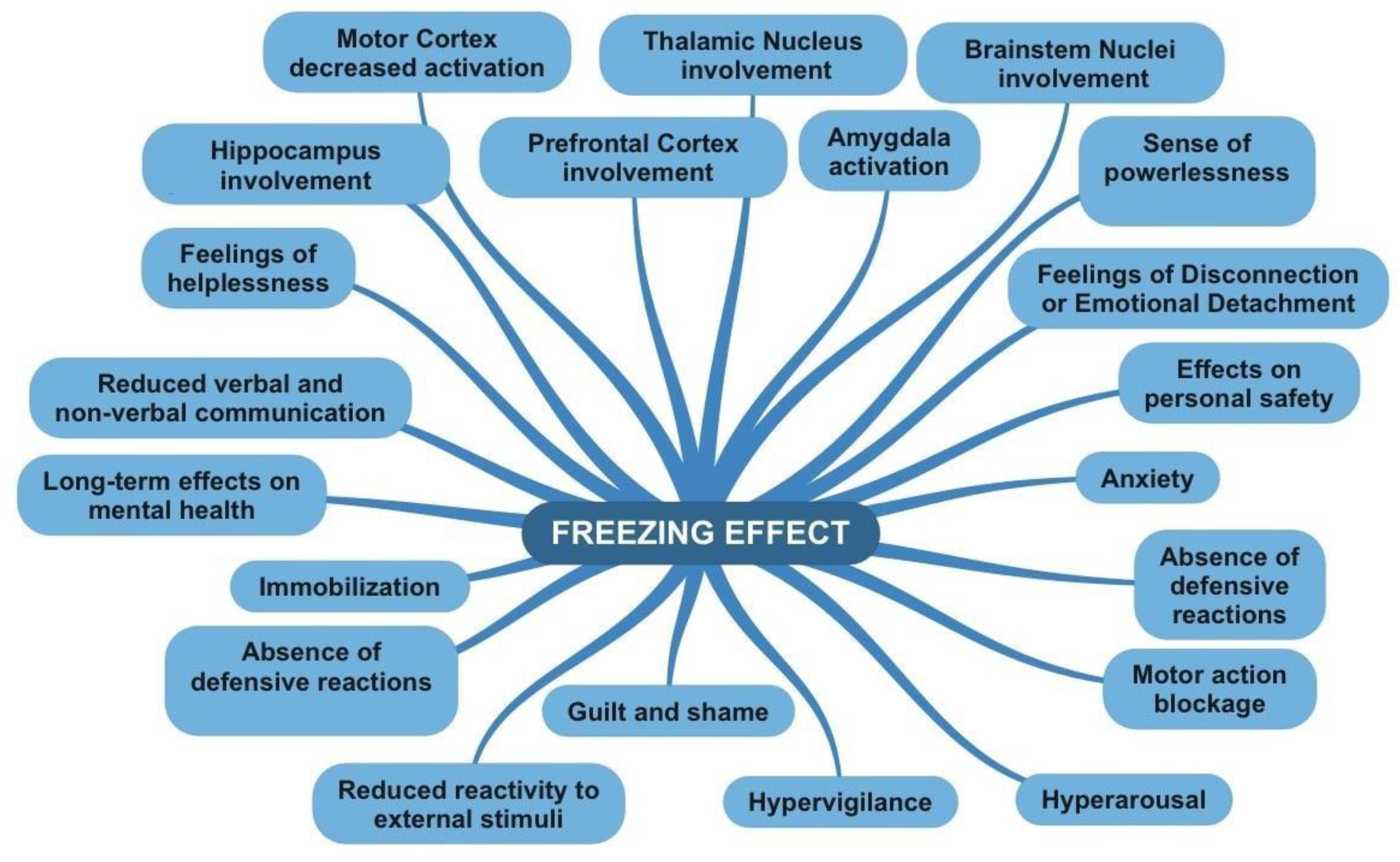

2. The Freezing Effect

2.1. Fight or Flight Response and Freezing Mechanism

2.2. The Neural Basis of the Freezing Effect

2.3. Psychological Consequences of Freezing Effect: From Immediately to the Long-Term

3. The Bystander Effect

3.1. Definition and Brief Analysis of the Phenomenon

3.2. The Background: Kitty Genovese’s Case

3.3. From the Real World to the Laboratory

3.4. Victim and Bystander: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

3.5. Psychological Consequences in Bystander Effect: Now and in the Future

4. A Comparison between the Two Phenomena

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

8. Notes on Preventive Strategies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gray, J.A. Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cogn. Emot. 1990, 4, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, L.B. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage; Branford: Boston, MA, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.A.; McNaughton, N. The Neuropsychology of Anxiety: An Enquiry into the Functions of the Septo-Hippocampal System; Clarendon Press/Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs, K. Freeze for action: Neurobiological mechanisms in animal and human freezing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, K.; Hagenaars, M.A.; Stins, J. Facing freeze: Social threat induces bodily freeze in humans. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenaars, M.A.; Roelofs, K.; Stins, J.F. Human freezing in response to affective films. Anxiety Stress Coping 2014, 27, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenaars, M.A.; Stins, J.F.; Roelofs, K. Aversive life events enhance human freezing responses. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagliano, L.; Cappuccio, A.; Trojano, L.; Conson, M. Approaching threats elicit a freeze-like response in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 561, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojowska, M.; Ling, S.; Roelofs, K.; Hermans, E.J. Visuocortical changes during a freezing-like state in humans. Neuroimage 2018, 179, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, R. The fight-or-flight response: A cornerstone of stress research. In Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Spierer, D.K.; Griffiths, E.; Sterland, T. Fight or Flight; The Tactical Edge: Clarksville, TN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, A.S.; Van Nguyen, X.; Karpitskiy, V.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Loewy, A.D. Central command neurons of the sympathetic nervous system: Basis of the fight-or-flight response. Science 1995, 270, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taelman, J.; Vandeput, S.; Spaepen, A.; Van Huffel, S. Influence of mental stress on heart rate and heart rate variability. In Proceedings of the 4th European Conference of the International Federation for Medical and Biological Engineering: ECIFMBE 2008, Antwerp, Belgium, 23–27 November 2008; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1366–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Appelhans, B.M.; Luecken, L.J. Heart rate variability as an index of regulated emotional responding. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2006, 10, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misslin, R. The defense system of fear: Behavior and neurocircuitry. Neurophysiol. Clin. /Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 33, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dampney, R.A. Central mechanisms regulating coordinated cardiovascular and respiratory function during stress and arousal. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2015, 309, R429–R443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uvnäs-Moberg, K.; Arn, I.; Magnusson, D. The psychobiology of emotion: The role of the oxytocinergic system. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2005, 12, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracha, H.S. Freeze, flight, fight, fright, faint: Adaptationist perspectives on the acute stress response spectrum. CNS Spectr. 2004, 9, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalin, N.H.; Shelton, S.E.; Fox, A.S.; Oakes, T.R.; Davidson, R.J. Brain regions associated with the expression and contextual regulation of anxiety in primates. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 58, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalin, N.H.; Fox, A.S.; Kovner, R.; Riedel, M.K.; Fekete, E.M.; Roseboom, P.H.; Tromp, D.P.; Grabow, B.P.; Olsen, M.E.; Brodsky, E.K.; et al. Overexpressing corticotropin-releasing factor in the primate amygdala increases anxious temperament and alters its neural circuit. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, M.M.; Zhang, W.; Kaldewaij, R.; Koch, S.B.; Smit, A.; Figner, B.; Jonker, R.; Klumpers, F.; Roelofs, K. Human defensive freezing: Associations with hair cortisol and trait anxiety. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 133, 105417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelofs, K.; Elzinga, B.M.; Rotteveel, M. The effects of stress-induced cortisol responses on approach–avoidance behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niermann, H.C.; Figner, B.; Tyborowska, A.; van Peer, J.M.; Cillessen, A.H.; Roelofs, K. Defensive freezing links Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal-axis activity and internalizing symptoms in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 82, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzirbikova, Z.; Talarovičová, A.; Štefánik, P.; Olexová, L.; Kršková, L. Testosterone enhancement during pregnancy influences social coping and gene expression of oxytocin and vasopressin in the brain of adult rats. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2018, 78, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuss, P. Anxiety disorders and GABA neurotransmission: A disturbance of modulation. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-León, P.; Miranda-Páez, A.; Valencia-Flores, K.; Sánchez-Castillo, H. Defensive and emotional behavior modulation by serotonin in the periaqueductal gray. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskind, J.H.; Sagliano, L.; Trojano, L.; Conson, M. Dysfunctional Freezing Responses to Approaching Stimuli in Persons with a Looming Cognitive Style for Physical Threats. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskind, J.H.; Black, D.; Shahar, G. Cognitive vulnerability to anxiety in the stress generation process: Interaction between the Looming Cognitive Style and Anxiety Sensitivity. J. Anxiety Disord. 2010, 24, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darley, J.M.; Latané, B. Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 8, 377–383. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0025589 (accessed on 10 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Latané, B.; Darley, J.M. The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help? Appleton Century Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, D.G.; Resnick, H.S.; Milanak, M.E.; Miller, M.W.; Keyes, K.M.; Friedman, M.J. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J. Trauma. Stress 2013, 26, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Akiskal, H.S.; Yong, S.S.; Stratta, P.; Calderani, E.; Massimetti, E.; Akiskal, K.K.; Rossi, A.; Dell’Osso, L. Post-traumatic stress disorder in DSM-5: Estimates of prevalence and criteria comparison versus DSM-IV-TR in a non-clinical sample of earthquake survivors. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, G.R.; Hazler, R.J. Trauma reactions of bystanders and victims to repetitive abuse experiences. Violence Vict. 2004, 19, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress Appraisal and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nester, M.S.; Cook, M.H.; Pugach, C.P.; Wisco, B.E. Exploring false negatives in self-reported trauma exposure status. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, A. (Ed.) The Psychology of Health and Illness; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 5, No. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Westphal, M.; Mancini, A.D. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R. Stress, Trauma, and Posttraumatic Growth: Social Context, Environment, and Identities; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach, D.; Vrana, S. The relationship among personality variables, exposure to traumatic events, and severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms. J. Trauma. Stress 2001, 14, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Ormrod, R.K.; Turner, H.A. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehuda, R. Risk and resilience in posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Understanding the impact of trauma. In Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti, A. The trauma factor: Examining the relationships among different types of trauma, dissociation, and psychopathology. J. Trauma Dissociation 2018, 19, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A.; Caretti, V. Linking the overwhelming with the unbearable: Developmental trauma, dissociation, and the disconnected self. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2016, 33, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. The neurobiology of childhood trauma and abuse. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2003, 12, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, G. Trauma, dissociation, and disorganized attachment: Three strands of a single braid. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2004, 41, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hart, O. Understanding trauma-generated dissociation and disorganised attachment: Giovanni Liotti’s lasting contributions. Attachment 2018, 12, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, A.N. Relational trauma, brain development, and dissociation. In Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, B.D.; Pollard, R. Homeostasis, stress, trauma, and adaptation: A neurodevelopmental view of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 1998, 7, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D. Childhood Victimization: Violence, Crime, and Abuse in the Lives of Young People; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Livia, D.; Petre, A. Effects of Bullying on Adolescent Suicidal Behavior. Glob. J. Arts Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 12, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, T.G. Systemic Environmental Factors, Neural Correlates and Psychosis Vulnerability. Ph.D. Dissertation, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M.S. The Different Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Relationships. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richters, J.E.; Martinez, P. The NIMH community violence project: I. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence. Psychiatry 1993, 56, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremne, J.D.; Vermetten, E. Stress and development: Behavioral and biological consequences. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001, 13, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boney-McCoy, S.; Finkelhor, D. Prior victimization: A risk factor for child sexual abuse and for PTSD-related symptomatology among sexually abused youth. Child Abus. Negl. 1995, 19, 1401–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazler, R.J.; Hoover, J.H.; Oliver, R. Student Perceptions of Victimization by Bullies in School. J. Humanist. Educ. Dev. 1991, 29, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, J.H.; Oliver, R.; Hazler, R.J. Bullying: Perceptions of adolescent victims in the Midwestern USA. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1992, 13, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, J.V. Bullied to Death: Perceptions of Peer Abuse and Suicidal Behaviour during Adolescence. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2000, 21, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazler, R.J.; Carney, J.V. Empowering Peers to Prevent Youth Violence. J. Humanist. Couns. Educ. Dev. 2002, 41, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, E.A. Victims and Victimology: The Facts and the Rhetoric. Int. Rev. Vict. 1989, 1, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.M.; Gilligan, C. Listening for voice in narratives of relationship. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 1991, 1991, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, S.P.; Safran, J.S.; Barcikowski, R.S. Differences in Teacher Tolerance: An Illusory Phenomena? Behav. Disord. 1985, 11, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzkovich, Y.; Barhon, E.; Lev-Wiesel, R. Health and Risk Behaviors of Bystanders: An Integrative Theoretical Model of Bystanders’ Reactions to Mistreatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, R.; Eschenbeck, H.; Hock, M. Bystanders of bullying: Social-cognitive and affective reactions to school bullying and cyberbullying. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2018, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Selective Moral Disengagement in the Exercise of Moral Agency. J. Moral Educ. 2002, 31, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, D.S. Recognition of Social Pain among Peers: Rethinking the Role of Bystanders in Bullying and Cyberbullying. Smith Coll. Stud. Soc. Work 2016, 86, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, R.; Jungert, T. Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, L. Defender self-efficacy and moral disengagement on social support and bystander behaviors among primary school students: A multilevel moderated mediation model. Psicol. Refl. Crit. 2023, 36, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortensius, R.; de Gelder, B. From Empathy to Apathy: The Bystander Effect Revisited. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, A.; Schwartz, S. They Know I Saw It: Evaluation Apprehension and Diffusion of Responsibility in Bystander Reactions to a Violent Crime; ERIC: New Haven, CT, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.A. The Psychology of Fear and Stress, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Latané, B.; Nida, S. Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 89, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanselow, M.S. Neural organization of the defensive behavior system responsible for fear. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 1994, 1, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, C. Review of Child Victims: Crime, Impact and Criminal Justice, by J. Morgan & L. Zedner. Mod. Law Rev. 1993, 56, 611–613. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1096836 (accessed on 4 July 1993).

- Graziano, W.G.; Habashi, M.M. Motivational processes underlying both prejudice and helping. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 14, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, J. Cognitive paralysis in an emergency: The role of the supervisory attentional system. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2005, 76, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schiller, D.; Alessandra, N.C.; Alia-Klein, N.; Becker, S.; Cromwell, H.C.; Dolcos, F.; Soreq, H. The human affectome. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 2023, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, A.; Rizzo, A.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Celebre, L.; Silvestri, M.C.; Zoccali, R.A.; Mento, C. Hyperarousal scale: Italian cultural validation, age and gender differences in a nonclinical population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Liu, C.; Teng, Z. The effect of everyday moral sensitivity on bullying bystander behavior: Parallel mediating roles of empathy and moral disengagement. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 38, 7678–7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscatello, M.R.A.; Rizzo, A.; Celebre, L.; Mento, C.; Pandolfo, G.; Cedro, C.; Battaglia, F.; Zoccali, R.A.; Bruno, A. The wounds of childhood: Early trauma subtypes, salience and hyperarousal in a sample of adult psychiatric patients. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mento, C.; Rizzo, A.; Alfa, R.; Carlotta, V.; Lipari, E.; Bruno, A.; Cedro, C.; Pandolfo, G.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Zoccali, R.A. The role of basic symptoms and aberrant salience in borderline personality disorder. J. Clin. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağiş, Z.G.; Akçe, İ.; Aziz, I.A.; Rizzo, A.; Nucera, G.; Bragazzi, N.; Yildirim, M. The mediating role of peritraumatic stress in the relationship between childhood psychological maltreatment and optimism and pessimism among earthquake survivors in Turkey. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2023, 8, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettrey, H.H.; Marx, R.A. The Effects of Bystander Programs on the Prevention of Sexual Assault across the College Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 48, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.; Mattei, A.; Arnone, F.; Barbieri, A.; Basile, V.; Cedro, C.; Celebre, L.; Mento, C.; Rizzo, A.; Silvestri, M.C.; et al. Lifetime psychiatric comorbidity and diagnostic trajectories in an Italian psychiatric sample. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettrey, H.H.; Thompson, M.P. Can a Technology-Amplified Bystander Effect Impede the Prevention of Campus Sexual Assault? Findings from an Experimental Vignette Study. J. Sch. Violence 2022, 22, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Princiotta, E.; Iuele, G. Exploring the link between smartphone use, recorded violence, and social sharing in 80 case studies in Italy. Psych 2023, 5, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, V.; Brough, P.; Daly, K. Fight, flight or freeze: Common responses for follower coping with toxic leadership. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2016, 32, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, M.; Turan, M.E.; Albeladi, N.S.; Crescenzo, P.; Rizzo, A.; Nucera, G.; Ferrari, G.; Navolokina, A.; Szarpak, L.; Chirico, F. Resilience and perceived social support as predictors of emotional well-being. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2023, 8, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcelli, A.J.; Delgado, M.R. Stress and Decision Making: Effects on Valuation, Learning, and Risk-taking. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 14, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bystander Effect | Freezing Effect |

|---|---|

| Definition: It occurs in emergency or danger situations involving another person, resulting in a lack of action. | Definition: It occurs in emergency or danger situations involving the person, resulting in a lack of action. |

| What happens on an emotional level? | What happens on an emotional level? |

| Fear of social judgment: Individuals may experience fear of being judged or evaluated by others present. They might worry about appearing foolish, intrusive, or doing something wrong. This fear of social judgment can hinder the expression of emotions and action, leading to feelings of anxiety or shame [63]. | Hypersensitivity and Hypervigilance: In some situations, freezing may be accompanied by an increased sensitivity to stimuli in the surrounding environment. People can be hyperaware and hypersensitive to danger signals or any changes in the situation, attempting to detect any potential threat [64]. |

| Emotional dissonance: In some cases, people may experience emotional dissonance when their personal emotional reaction conflicts with that of others present. For instance, an individual might feel concerned or compassionate for someone in distress, but if others appear indifferent or do not react, emotional tension may arise. This disparity between personal emotions and those of others can generate emotional discomfort or frustration. | Sense of powerlessness: During freezing, individuals may feel powerless or unable to act. This can generate frustration, resignation, or a sense of being trapped in the situation with no way out [64]. |

| Feelings of Disconnection or Emotional Detachment: During freezing, some individuals may experience a sense of emotional disconnection or detachment from the situation. This can be a form of psychological defense that allows them to cope with danger or threat without being overwhelmed by the intense emotions associated with them. | |

| What happens at the behavioral level? | What happens at the behavioral level? |

| Immobilization or inaction: The bystander effect manifests through the immobility or inaction of individuals involved. People may remain passive and refrain from taking any action to help or intervene in the situation of danger or emergency. | Immobilization: During freezing, the individual may remain still and frozen in the position they were in at the moment of perceiving danger. The lack of voluntary movements is a key characteristic of freezing [66]. |

| Difficulty in decision-making: People in the bystander effect may experience difficulty in making decisions regarding the action to take. They may feel indecisive about what to do or may seek guidance or initiative from others [65]. | Absence of defensive reactions: Unlike other defense responses such as flight or fight, in freezing, the individual shows no active reaction to protect themselves or avoid the danger. There is no attempt to escape the threat or defend against it. |

| Cognitive dissonance: The bystander effect can generate cognitive dissonance, a discrepancy between what a person knows is right (helping someone in danger) and their actual behavior (remaining still or inactive). This discrepancy can create a sense of emotional discomfort and ambivalence. | Reduced verbal and non-verbal communication: During freezing, the individual may exhibit reduced verbal and non-verbal communication. Gestures, facial expressions, or words may be limited or absent as energy and attention are focused on maintaining immobility [1]. |

| Diffusion of responsibility: Another behavioral aspect of the bystander effect is the diffusion of responsibility. People tend to feel less responsible to intervene if they are surrounded by others, if someone else will take care of the situation. | Motor action blockage: Freezing is characterized by a blockage of motor actions. The individual may temporarily lose the ability to move or perform tasks that require voluntary action. |

| Conformity to others’ behavior: The bystander effect can lead to conformity to the behavior of others present in the situation. People may observe the behavior of others and model their reaction based on what others are doing or not doing. | Reduced reactivity to external stimuli: During freezing, the individual may show reduced reactivity to external stimuli. They may be less sensitive to sounds, voices, or surrounding events as attention is focused on the perceived danger or threat. |

| Reduced emotional involvement: People in the bystander effect may experience reduced emotional involvement in the danger or emergency. Since there are other people present who are not reacting, the individual may feel less emotionally engaged or less motivated to intervene. | Increased hypervigilance: Despite immobility, the individual may exhibit increased hypervigilance toward the surrounding environment. They may be hypersensitive to danger signals and maintain a high state of alertness for potential threats. |

| Which brain areas are activated? | Which brain areas are activated? |

| Prefrontal Cortex: The prefrontal cortex is involved in planning, processing social information, and assessing risks. Under the bystander effect, reduced activation of the prefrontal cortex has been observed, which could be correlated with a decrease in individual motivation or attention toward the situation [67]. | Prefrontal Cortex: The prefrontal cortex is involved in many higher cognitive functions, including evaluation, planning, and emotional control. During freezing, the prefrontal cortex may be engaged in evaluating the situation and regulating emotional responses [10]. |

| Amygdala: The amygdala is involved in the emotional response, particularly in the detection and processing of emotions such as fear. During the bystander effect, the amygdala may show reduced activation, as individual emotional engagement may be attenuated by the presence of other people. | Amygdala: The amygdala is a key region involved in the fear and threat response. During freezing, the amygdala may show increased activation in response to the perception of danger or threat. |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex: The anterior cingulate cortex is involved in emotion regulation, attention, and the evaluation of error or conflict situations. Under the bystander effect, the activation of the anterior cingulate cortex may be reduced, suggesting decreased awareness, or monitoring of emergency situations. | Hippocampus: The hippocampus is involved in memory and learning. During freezing, the hippocampus may be involved in processing and remembering information related to the dangerous or threatening situation. |

| Caudate Nucleus: The caudate nucleus is involved in the decision-making process and regulation of behavior. Under the bystander effect, decreased activation of the caudate nucleus has been observed, which may be related to reduced motivation for action or inhibition of behavioral responses. | Thalamic Nucleus: The thalamic nucleus plays a role in transmitting sensory information and regulating attention. During freezing, the thalamic nucleus may be involved in filtering and transmitting sensory information relevant to the perception of danger. |

| Supplementary Motor Cortex: The supplementary motor cortex is involved in the planning and execution of voluntary movements. Under the bystander effect, the supplementary motor cortex may show reduced activation, as immobility and the inhibition of motor responses are characteristic of the bystander effect. | Brainstem Nuclei: Brainstem nuclei, such as the locus coeruleus and the raphe nucleus, are involved in regulating arousal and physiological responses to stress. During freezing, these nuclei may be activated to prepare the body to respond to the threat or danger. |

| Motor Cortex: The motor cortex is involved in the generation and execution of voluntary movements. During freezing, the motor cortex may show reduced activation, as freezing involves immobility and the inhibition of motor responses. | |

| Psychological Consequences: | Psychological Consequences: |

| Increased anxiety and stress: The bystander effect can lead to increased emotional anxiety and stress. Awareness of the danger or the responsibility to intervene can cause a sense of agitation and worry [65]. | Anxiety and hypervigilance: After freezing, some individuals may develop increased anxiety and hypervigilance. They may become hypersensitive to danger signals, overly alert, and constantly vigilant of potential threats [20,28]. |

| Reduced empathy: The bystander effect may result in reduced empathy toward the victim or the person in danger. The presence of others who do not react can create a social climate where individual empathy is suppressed or minimized [65,66]. | Feelings of helplessness: During freezing, individuals may experience a sense of helplessness or an inability to act. This can lead to frustration and a loss of confidence in one’s ability to handle dangerous situations. |

| Diminished autonomy and self-efficacy: Being part of the bystander effect can undermine the sense of autonomy and control over one’s life. People may feel powerless or unable to make decisions and act independently, creating a perception of reduced self-efficacy [70]. | Effects on personal safety: Freezing can have consequences for the perception of personal safety. After experiencing freezing, people may feel more vulnerable or insecure about their ability to defend themselves or handle similar situations in the future. |

| Guilt and Remorse: Individuals experiencing the bystander effect may experience a profound sense of guilt and remorse for not taking action or providing help when necessary. These feelings may come from realizing that not acting could have made the situation worse or caused harm to the victim [65,66]. | Guilt and shame: After freezing, some individuals may experience guilt or shame for not reacting or taking action to protect themselves or others. These feelings may stem from the perception of having failed to address the situation or fulfill their duty. |

| Shame and compromised self-esteem: Being a spectator in a situation where someone is in danger can generate shame and a sense of compromised self-esteem. Individuals may feel inadequate or incapable of intervening, negatively impacting their self-perception [69,70]. | Long-term effects on mental health: In some cases, the experience of freezing can have long-term consequences on mental health. Feelings of helplessness, guilt, or shame can contribute to the development of psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [31,33]. |

| Long-term effects: In some cases, the experience of being involved in the bystander effect can have long-term consequences on mental health. Persistent guilt, shame, and remorse can contribute to the development of disorders such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder [65,66,69,70]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siligato, E.; Iuele, G.; Barbera, M.; Bruno, F.; Tordonato, G.; Mautone, A.; Rizzo, A. Freezing Effect and Bystander Effect: Overlaps and Differences. Psych 2024, 6, 273-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych6010017

Siligato E, Iuele G, Barbera M, Bruno F, Tordonato G, Mautone A, Rizzo A. Freezing Effect and Bystander Effect: Overlaps and Differences. Psych. 2024; 6(1):273-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych6010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiligato, Elena, Giada Iuele, Martina Barbera, Francesca Bruno, Guendalina Tordonato, Aurora Mautone, and Amelia Rizzo. 2024. "Freezing Effect and Bystander Effect: Overlaps and Differences" Psych 6, no. 1: 273-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych6010017

APA StyleSiligato, E., Iuele, G., Barbera, M., Bruno, F., Tordonato, G., Mautone, A., & Rizzo, A. (2024). Freezing Effect and Bystander Effect: Overlaps and Differences. Psych, 6(1), 273-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych6010017