COVID-19 Vaccination: Sociopolitical and Economic Impact in the United States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Mentality on COVID-19 and Attitude toward Vaccine Acceptance

1.2. COVID-19 Vaccine Safety and Efficacy

1.3. Socioeconomic and Sociopolitical Impact on COVID-19 Vaccination

2. Materials and Methods

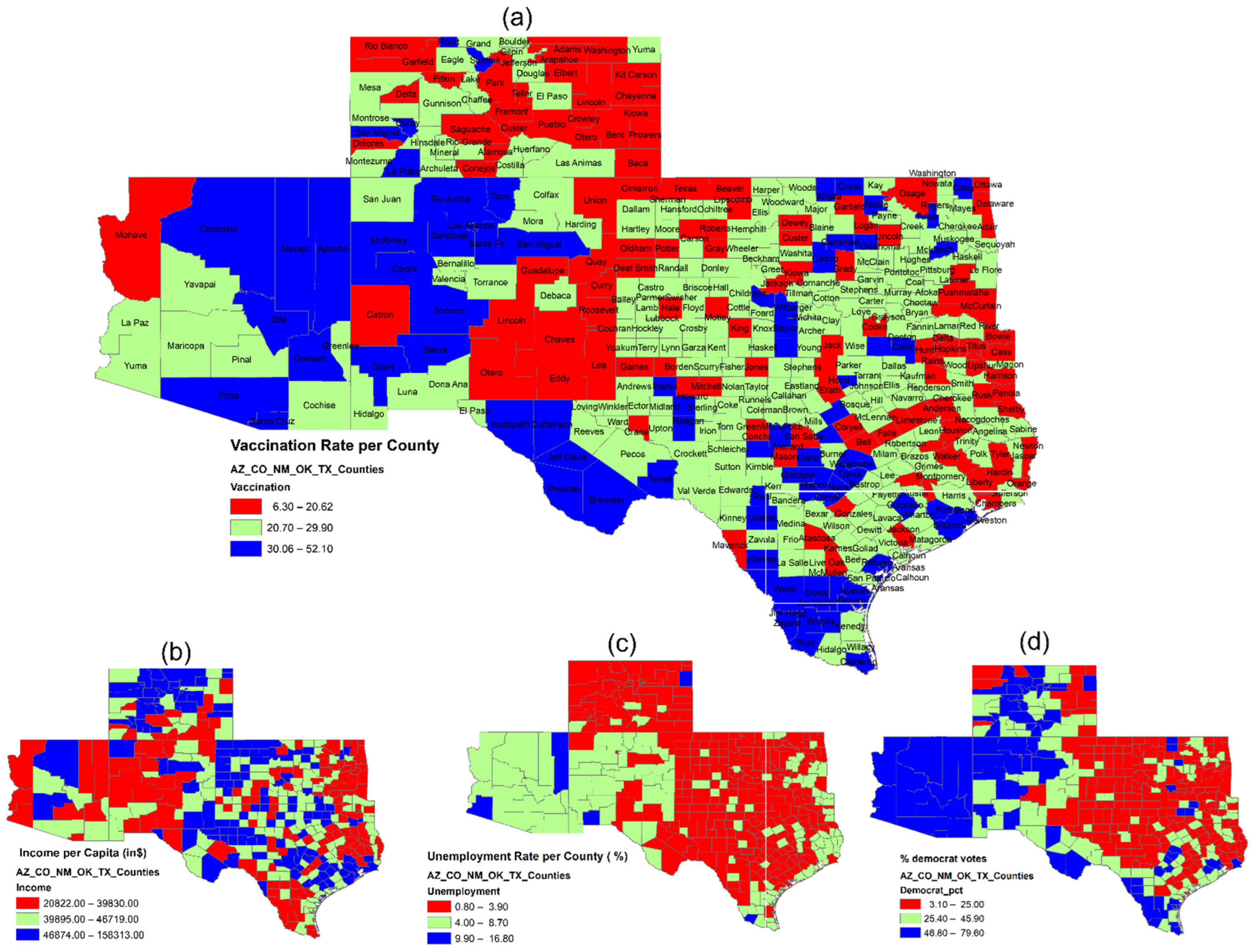

2.1. Data Sources and Variables

- State: Five states (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas) across the United States.

- Employment status: The unemployment rate of 2019 is used to denote county-wide employment status, retrieved from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The expectation is that it will disclose an inverse correlation between a county’s unemployment rate and its COVID-19 vaccination rate. That is, citizens who are unemployed may be inclined to refuse vaccination due to economic reasons or not being subject to the workplace vaccination requirement.

- Political choice: The debates over the political ideology of COVID-19 suggested potential polarization over the vaccination decision. Hence, county-based voting results of the 2020 presidential election released by Politico (https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/, accessed on 15 June 2021) were analyzed. In brief, it is hypothesized that counties with a high proportion of Democratic voters would be more likely to get vaccinated.

- Age: As COVID-19 vaccination was authorized on an age basis, various age classifications were used in this study following the county data from ‘County Population by Characteristics: 2010–2019’ of the 2010 US Census. As guided by CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) [30], COVID-19 vaccines were first administered to healthcare personnel and long-term care facilities’ residents categorized as Phase 1a, and almost concurrently given to the seniors aged ≥75 as Phase 1b, followed by Phase 1c covering persons aged 65–74 years and those aged 16–64 years with high-risk medical conditions. Based on such categorization, the age groups in this analysis were structured as shown in Table 1.

- Occupation: Worker’s occupation is classified into ‘farm’ and ‘non-farm’ categories from the 2019 data of the Bureau of Economic Analysis, where the percentage of farm employment (labeled as ‘Farm Worker’ in the model) is calculated by taking the number of workers hired as farm labor over the total population per county. The assumption is that counties with more farmworkers are more likely to have lower COVID-19 vaccination rates.

- Area of residence: We examine whether the COVID-19 vaccination rate varies in the area of residence by extending the model to cover the rural and urban communities based on the 2010 Census data. Counties with less than 50% of the population living in rural areas are classified as urban, in contrast to those with 50-plus percent of rural residents. As indicated in the recent Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) of the CDC [31], access to COVID-19 vaccines is normally lower, at 38.9%, in rural counties than in cities. This study, therefore, assumes a lower vaccination rate across rural areas.

- Education: The education level also serves as a determinant for COVID-19 vaccination. Soares et al. [32] found that individuals with secondary or basic (lower) education and the uneducated are more hesitant to get vaccinated, resulting in lower vaccination rates compared to those with college or university degrees. Based on Federal Reserve Economic Data, the percentage of the county population aged ≥18 who had obtained at least a high-school diploma was examined for the education effect on the vaccination choice. It is projected that a lack of college education would lead to county citizens’ vaccination hesitancy.

- Income: The COVID-19 pandemic has created much economic hardship for most people, as different income levels may potentially increase the acceptance or refusal of the vaccine. This study hence tries to disclose the effect of per capita income on vaccination following the data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, with the fundamental prediction resting on the higher lags in vaccination rates among counties with lower income.

- Race and ethnicity: Race and ethnicity are exogenous variables and important indicators in this analysis which aims to offer policy implications, possibly reducing racial and ethnic disparities to improve overall COVID-19 vaccine coverage across five states. CDC identified racial and ethnic discrimination, amid other factors, creating challenges to COVID-19 vaccination access and acceptance among minority groups [33]. Thus, it is assumed that lower vaccination rates prevail in counties dominated by minorities of Blacks, Asians, Native Americans, and Hispanics, diverging from those predominantly inhabited by Whites and non-Hispanics.

2.2. Statistical Method

3. Results

4. Discussion and Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gavi. The COVID-19 Vaccine Race. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/covid-19-vaccine-race (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccination (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- WHO. Vaccine Equity. Available online: https://www.who.int/campaigns/vaccine-equity (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Mayo Clinic. U.S. COVID-19 Map: What Do the Trends Mean for You? Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/coronavirus-covid-19/vaccine-tracker (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- El-Elimat, T.; AbuAlSamen, M.M.; Almomani, B.A.; Al-Sawalha, N.A.; Alali, F.Q. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-F. COVID-19 Crisis and International Business and Entrepreneurship: Which Business Culture Enhances Post-Crisis Recovery? Glob. J. Entrep. 2021, 5, 1+. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A668712689/AONE?u=anon~7d06e3e7&sid=googleScholar&xid=84aecd6f (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- De Coninck, D.; Frissen, T.; Matthijs, K.; d’Haenens, L.; Lits, G.; Champagne-Poirier, O.; Carignan, M.E.; David, M.D.; Pignard-Cheynel, N.; Salerno, S.; et al. Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: Comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 646394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.L. Science Denial and COVID Conspiracy Theories: Potential Neurological Mechanisms and Possible Responses. JAMA 2020, 324, 2255–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machingaidze, S.; Wiysonge, C.S. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Loe, B.S.; Yu, L.M.; Freeman, J.; Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; Shanyinde, M.; Harris, V.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; et al. Effects of different types of written vaccination information on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK (OCEANS-III): A single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e416–e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, A.A.; García, L.Y. Willingness to Pay for a COVID-19 Vaccine. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2021, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.Y.; Cerda, A.A. Authors’ Reply to Sprengholz and Betsch: “Willingness to Pay for a COVID-19 Vaccine”. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2021, 19, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, A.A.; García, L.Y. Hesitation and Refusal Factors in Individuals’ Decision-Making Processes Regarding a Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 626852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Papaluca, M.; Molokhia, M. Assessing the long-term safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Failla, G.; Ricciardi, W. Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: A systematic review. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 40, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Milstein, A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021726118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.J.; Moreira, E.D., Jr.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Polack, F.P.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine through 6 Months. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1761–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.P.; Gupta, V. COVID-19 Vaccine: A comprehensive status report. Virus Res. 2020, 288, 198114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Dudley, M.Z.; Chen, X.; Bai, X.; Dong, K.; Zhuang, T.; Salmon, D.; Yu, H. Evaluation of the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid review. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.M.C.; Plotkin, S.A. Impact of Vaccines; Health, Economic and Social Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boserup, B.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2753–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, D. Vaccination, politics and COVID-19 impacts. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Dugas, M.; Ramaprasad, J.; Luo, J.; Li, G.; Gao, G.G. Socioeconomic privilege and political ideology are associated with racial disparity in COVID-19 vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2107873118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Anneser, E.; Toppo, A.; Allen, J.D.; Scott Parott, J.; Corlin, L. Disparities in national and state estimates of COVID-19 vaccination receipt and intent to vaccinate by race/ethnicity, income, and age group among adults ≥ 18 years, United States. Vaccine 2022, 40, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Q.X.; Lim, S.R.; Yau, C.E.; Liew, T.M. Examining the Prevailing Negative Sentiments Related to COVID-19 Vaccination: Unsupervised Deep Learning of Twitter Posts over a 16 Month Period. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, A.E.; Reither, E.N.; Mamelund, S.E.; Lim, S. Black-white disparities in 2009 H1N1 vaccination among adults in the United States: A cautionary tale for the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine 2021, 39, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njoku, A.; Joseph, M.; Felix, R. Changing the Narrative: Structural Barriers and Racial and Ethnic Inequities in COVID-19 Vaccination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, D.B.G.; Shah, A.; Doubeni, C.A.; Sia, I.G.; Wieland, M.L. The Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooling, K.; Marin, M.; Wallace, M.; McClung, N.; Chamberland, M.; Lee, G.M.; Talbot, H.K.; Romero, J.R.; Bell, B.P.; Oliver, S.E. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Updated Interim Recommendation for Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 69, 1657–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, B.P.; Sterrett, N.; Weller, D.; Zell, E.; Reynolds, L.; Toblin, R.L.; Murthy, N.; Kriss, J.; Rose, C.; Cadwell, B.; et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Between Urban and Rural Counties—United States, December 14, 2020-April 10, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Rocha, J.V.; Moniz, M.; Gama, A.; Laires, P.A.; Pedro, A.R.; Dias, S.; Leite, A.; Nunes, C. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.D.; Blackstock, A.J.; Taylor, E.V.; El Burai Felix, S.; Adjei, S.; Singleton, C.M.; Fuld, J.; Bruce, B.B.; Boehmer, T.K. Trends in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19 Hospitalizations, by Region—United States, March-December 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardosh, K.; de Figueiredo, A.; Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Doidge, J.; Lemmens, T.; Keshavjee, S.; Graham, J.E.; Baral, S. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricorian, K.; Turner, K. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Beliefs among Black and Hispanic Americans. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndugga, N.; Hill, L.; Artiga, S.; Alam, R.; Haldar, S. Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. KFF, Published: 7 April 2022. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/ (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Ng, Q.X.; Yau, C.E.; Yaow, C.; Lim, Y.L.; Xin, X.; Thumboo, J.; Fong, K.Y. Impact of COVID-19 on Environmental Services Workers in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 130, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Variable | Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| State | State | States (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas) | |

| Employment status | Unemployment | Unemployment rate in 2019 | Bureau of Labor Statistics published by Economic Research Service of USDA a https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?ID=17828 (accessed on 8 June 2021) |

| Political choice | Democrat | Percent of democrat votes, 2020 election result | Politico https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/ (accessed on 15 June 2021) |

| Democrat_1 | Democrat = 1, Republican = 0 | ||

| Age | Age_1417 | Percent of county resident population aged between 14 and 17 | 2010 US Census (1 April 2010 to 1 July 2019) https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-detail.html (accessed on 15 June 2021) |

| Age_1864 | Percent of county resident population aged between 18 and 64 | ||

| Age_65over | Percent of county resident population aged 65 years and over | ||

| Age_14over | Percent of county resident population aged 14 years and over | ||

| Age_18over | Percent of county resident population aged 18 years and over | ||

| Age_median | Median age of county resident population | ||

| Occupation | FarmWorker | Percent of workers hired farm labor | Bureau of Economic Analysis 2019 https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&acrdn=6 (accessed on 10 August 2021) |

| Area of residence | Rural_pct | Percent of the county population living in rural areas | 2010 US Census https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&acrdn=6 (accessed on 15 June 2021) |

| Urban_1 | Urban = 1 if Rural_pct ≤ 50, Rural = 0 if Rural_pct > 50 | ||

| Education | HS graduate | Percent of county population who are a high school graduates or higher (5-year estimate) for the population 18 years old and over | Federal Reserve Economic Data 2019 https://fred.stlouisfed.org/release/tables?rid=330&eid=391443 (accessed on 12 July 2021) |

| Income | Income | Per capita personal income | Bureau of Economic Analysis 2019 https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&acrdn=6 (accessed on 15 June 2021) |

| Race/ethnicity | White | Percent of county population by race (White) | 2010 US Census https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-detail.html (accessed on 15 June 2021) |

| Black | Percent of county population by race (Black) | ||

| Asian | Percent of county population by race (Asian) | ||

| Indian | Percent of county population by race (Indian) | ||

| Other | Percent of county population by race (other) | ||

| Hispanic | Percent of county population by Hispanic origin (Hispanic) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | Percent of county population by non-Hispanic origin (non-Hispanic) | ||

| Vaccination | Vaccination rate | Percent of people who are fully vaccinated based on the jurisdiction and county where recipient lives as of 1 May 2021 | CDC b https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/COVID-19-Vaccinations-in-the-United-States-County/8xkx-amqh (accessed on 1 June 2021), Texas vaccination data https://data.democratandchronicle.com/covid-19-vaccine-tracker/texas/48/ (accessed on 22 June 2021) |

| All * | AZ | CO | NM | OK | TX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 443 | 15 | 64 | 33 | 77 | 254 |

| Unemployment (%) | 3.61 ± 1.47 | 6.64 ± 3.28 | 2.74 ± 0.81 | 5.44 ± 1.64 | 3.25 ± 0.92 | 3.51 ± 1.09 |

| Democrat (%) | 29.07 ± 17.38 | 62.50 ± 7.24 | 41.73 ± 18.59 | 44.79 ± 16.91 | 20.27 ± 7.93 | 24.53 ± 14.15 |

| Democrat_1 | 75 (16.9) | 15 (100) | 24 (37.5) | 14 (42.4) | 0 (0) | 22 (8.7) |

| Age (%) | ||||||

| 14–17 years old | 5.29 ± 0.89 | 5.02 ± 0.88 | 4.67 ± 0.85 | 4.93 ± 0.97 | 5.39 ± 0.48 | 5.48 ± 0.90 |

| 18–64 years old | 57.88 ± 4.22 | 55.95 ± 5.31 | 60.01 ± 5.33 | 56.40 ± 4.28 | 57.69 ± 2.87 | 57.70 ± 4.00 |

| ≥ 65 years old | 19.15 ± 5.56 | 21.70 ± 7.98 | 20.02 ± 5.59 | 22.15 ± 7.67 | 18.63 ± 2.85 | 18.55 ± 5.53 |

| ≥ 14 years old | 82.32 ± 3.16 | 82.67 ± 3.19 | 84.71 ± 3.30 | 83.49 ± 3.43 | 81.71 ± 1.52 | 81.74 ± 3.15 |

| ≥ 18 years old | 77.03 ± 3.88 | 77.65 ± 4.03 | 80.04 ± 4.03 | 78.55 ± 4.29 | 76.32 ± 1.82 | 76.25 ± 3.82 |

| Median (years old) | 40.31 ± 6.02 | 41.23 ± 8.35 | 42.94 ± 6.14 | 42.65 ± 8.06 | 39.56 ± 3.38 | 39.52 ± 5.92 |

| Farm Worker (%) | 5.93 ± 5.96 | 1.58 ± 1.83 | 5.52 ± 6.98 | 4.67 ± 5.91 | 5.82 ± 4.65 | 6.48 ± 6.10 |

| Rural_pct (%) | 56.13 ± 31.67 | 34.11 ± 19.75 | 58.68 ± 36.63 | 48.42 ± 30.54 | 63.64 ± 26.13 | 55.52 ± 31.90 |

| Urban_1 | 202 (45.6) | 12 (80) | 30 (46.9) | 21 (63.6) | 21 (27.3) | 118 (46.5) |

| HS graduate (%) | 83.64 ± 7.97 | 84.48 ± 5.32 | 91.16 ± 4.84 | 84.36 ± 5.42 | 86.11 ± 3.74 | 80.85 ± 8.46 |

| Income ($) | 45,928 ± 13,399 | 39,197 ± 5887 | 53,080 ± 19,436 | 41,800 ± 9196 | 41,248 ± 8238 | 46,479 ± 12,720 |

| Race (%) | ||||||

| White | 86.46 ± 10.38 | 78.32 ± 19.40 | 91.83 ± 4.13 | 84.94 ± 15.84 | 77.17 ± 10.45 | 88.61 ± 7.49 |

| Black | 5.12 ± 5.62 | 2.36 ± 1.85 | 2.01 ± 2.41 | 1.96 ± 1.32 | 3.80 ± 3.49 | 6.88 ± 6.46 |

| Asian | 1.31 ± 1.76 | 1.57 ± 1.15 | 1.48 ± 1.42 | 1.24 ± 1.12 | 0.98 ± 0.98 | 1.35 ± 2.08 |

| Indian | 4.31 ± 8.17 | 15.10 ± 20.69 | 2.22 ± 2.06 | 9.32 ± 16.14 | 11.79 ± 8.40 | 1.28 ± 0.51 |

| Other | 2.80 ± 1.95 | 2.66 ± 0.72 | 2.47 ± 0.73 | 2.55 ± 0.63 | 6.26 ± 2.17 | 1.88 ± 0.68 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 29.63 ± 22.40 | 31.71 ± 20.83 | 20.16 ± 13.54 | 48.69 ± 17.05 | 9.71 ± 7.58 | 35.46 ± 22.97 |

| Non-Hispanic | 70.37 ± 22.40 | 68.29 ± 20.83 | 79.84 ± 13.54 | 51.31 ± 17.05 | 90.29 ± 7.58 | 64.54 ± 22.97 |

| Vaccination rate (%) (as of 1 May 2021) | 24.59 ± 6.87 | 32.81 ± 7.96 | 19.63 ± 7.14 | 26.49 ± 9.64 | 24.68 ± 4.46 | 25.08 ± 6.12 |

| (M1) | (M2) | (M3.1) | (M3.2) | (M3.3) | (M3.4) | (M3.5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 1+ Age_65over | Model 1+ Age_65over + Race (White) | Model 1+ Age_65over + Race (Black) | Model 1+ Age_65over + Race (Asian) | Model 1+ Age_65over + Race (Indian) | Model 1+ Age_65over + Race (Hispanic) | |

| R-squared | 0.382 | 0.404 | 0.405 | 0.488 | 0.405 | 0.439 | 0.414 |

| State (NM *) | |||||||

| AZ | 2.210 (0.206) | 2.116 (0.218) | 2.172 (0.207) | 1.542 (0.334) | 2.181 (0.205) | 1.310 (0.435) | 3.440 (0.053) |

| CO | −6.287 (<0.001) | −5.778 (<0.001) | −5.901 (<0.001) | −5.582 (<0.001) | −5.736 (<0.001) | −4.815 (<0.001) | −4.861 (<0.001) |

| OK | 4.657 (<0.001) | 5.582 (<0.001) | 5.897 (<0.001) | 6.750 (<0.001) | 5.501 (<0.001) | 4.692 (<0.001) | 7.124 (<0.001) |

| TX | 3.453 (0.004) | 4.024 (0.001) | 4.076 (0.001) | 6.985 (<0.001) | 3.896 (0.001) | 5.178 (<0.001) | 4.776 (<0.001) |

| Unemployment | 0.285 (0.251) | 0.105 (0.672) | 0.151 (0.553) | 0.327 (0.158) | 0.112 (0.651) | −0.121 (0.622) | 0.127 (0.608) |

| Democrat | 0.242 (<0.001) | 0.243 (<0.001) | 0.247 (<0.001) | 0.260 (<0.001) | 0.237 (<0.001) | 0.232 (<0.001) | 0.222 (<0.001) |

| Farm Worker | 0.077 (0.220) | 0.019 (0.764) | 0.019 (0.765) | −0.002 (0.968) | 0.014 (0.827) | 0.012 (0.847) | −0.017 (0.788) |

| Rural_pct | 0.004 (0.711) | −0.013 (0.278) | −0.012 (0.319) | −0.012 (0.274) | −0.010 (0.409) | −0.023 (0.046) | −0.005 (0.692) |

| HS graduate | −0.012 (0.765) | −0.063 (0.136) | −0.053 (0.222) | 0.026 (0.525) | −0.072 (0.097) | −0.073 (0.076) | 0.033 (0.550) |

| Income | 8.077e-05 (<0.001) | 8.982e-05 (<0.001) | 8.658e-05 (<0.001) | 6.124e-05 (0.004) | 8.77e-05 (<0.001) | 1.009e-04 (<0.001) | 9.199e-05 (<0.001) |

| Age_65over | 0.245 (<0.001) | 0.230 (<0.001) | 0.149 (0.011) | 0.253 (<0.001) | 0.302 (<0.001) | 0.262 (<0.001) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.027 (0.395) | −0.419 (<0.001) | 0.161 (0.369) | 0.202 (<0.001) | 0.057 (0.008) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeon, S.; Lee, Y.-F.; Koumi, K. COVID-19 Vaccination: Sociopolitical and Economic Impact in the United States. Epidemiologia 2022, 3, 502-517. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia3040038

Jeon S, Lee Y-F, Koumi K. COVID-19 Vaccination: Sociopolitical and Economic Impact in the United States. Epidemiologia. 2022; 3(4):502-517. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia3040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeon, Soyoung, Yu-Feng Lee, and Komla Koumi. 2022. "COVID-19 Vaccination: Sociopolitical and Economic Impact in the United States" Epidemiologia 3, no. 4: 502-517. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia3040038

APA StyleJeon, S., Lee, Y.-F., & Koumi, K. (2022). COVID-19 Vaccination: Sociopolitical and Economic Impact in the United States. Epidemiologia, 3(4), 502-517. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia3040038