2. Conceptual Framing: Transdisciplinary Epistemic Community and Narrative for Sustainable Development

2.1. Rethinking the Foundations and Practical Arrangements for a Sustainable Development

The time has come for a social and ecological transition. That watchword recognises that global environmental changes can destabilise any mode of development and any promise of development [

10] constrained by social and planetary boundaries [

1].

Beyond the more or less fertile semantic and academic debates on the notion of transition, it is a case of questioning the conditions for alternatives that would seek to break with the cultural and ideological bases of development and growth and call upon other representations, other goals and other practices [

11]. In a nutshell, according to the doughnut theory, it is a case of trying to make the legitimate needs of current human and non-human populations compatible with the need for transformation toward a sustainable future [

12].

One of the necessary conditions for the implementation of alternatives to development is to recognise that knowledge production goes beyond the academic world. Ordinary citizens, activists, associative or trade union activists and intellectual professions grouped in collectives theorise and work on the implementation of new, local, scattered, isolated or networked practices, outside or together with political and academic institutions, in order to design alternative trajectories.

These “Emancipatory Social Science” initiatives and practices [

13] create new knowledge and assert appropriation modes, sometimes conflicting [

14], of the places that link humans and non-humans. In short, they create ontologies that are embedded in concrete practices [

15]. They are structured around cooperation, coordination and power struggles to redefine the ways of investing, inhabiting and valorising the territory and its resources [

16]. The issue is not that of degrowth but that of the inhabitants taking charge of a common project, formalised around a narrative. This narrative aims to articulate the long term (there are indeed historical hazards, history is not linear) and the different scales of action (avoiding withdrawal).

2.2. The Creation of a Transdisciplinary Epistemic Community (TEC)

For academic research, they are an opportunity to test new approaches, foremost among which is transdisciplinarity, defined as follows:

“Studies that integrate academic research, disciplines with different approaches to research, and involve non-academic participants (such as policy makers and other public or private sector stakeholders) in the study of a common goal and the creation of new knowledge, theories and options with a view to solving societal problems. Transdisciplinarity combines interdisciplinarity with a participatory approach. All parties involved, academic and non-academic, define and develop research objectives and methods to achieve a common goal together. This approach integrates disciplines, sub-disciplines and non-academic knowledge for an equitable sharing of power” [

10].

Its implementation implies the creation of a “transdisciplinary epistemic community” (TEC) [

16]. While the epistemic community initially brings together professional experts in a field, the transdisciplinary character adds citizen participation and expertise. These bring a plurality of perspectives and heuristics that are sometimes preferable to a high level of competence when it comes to proposing solutions that are qualified as robust [

17]. This is what is commonly referred to as “collective intelligence”, which, through the transdisciplinary approach, takes seriously the issue of the joint integration of different types and sources of knowledge, situated knowledge and life experience in support of transformative action. This is how a TEC is formed, one that is capable of grasping the challenges of the ecological transition and proposing alternative development trajectories.

In this experiment “Villages of the Future”, the objective is precisely to test the role of a TEC. By bringing in actors from outside villages (region, consultancy firm, experts, researchers), it is a case of co-constructing a collective narrative that carries a new common meaning. In this way, the consultants bring an outside viewpoint to the villages that allows inclusion of as many people as possible (for example, the elected officials of one of the villages realised that they were making little use of social networks and were therefore excluding the youngest populations). One of the consultants is associated with a theatre group: through their empathy the actors help the villagers to speak out and express their needs. The researchers participate in the articulation of scales by putting some local project leaders in contact with training centres or other territories involved in similar innovative initiatives.

Now, regarding this particular TEC, the point is to break with the path dependency of territorial development policies in Europe that, for the past thirty years, have been framed by cross-public funding (Europe, state, region) and growth objectives in a competitive universe. Growth-focused development policies are based on an essentially consumerist dimension of human needs, without guaranteeing their capacity to respond to social, or even spiritual, aspirations in an emancipatory vision geared towards the solidarity of inhabitants. These policies rely on various public action instruments, first and foremost the strengths and weaknesses diagnosis: strengths weaknesses opportunities threats (SWOT). Originally, this was a strategic analysis matrix developed for companies operating in a competitive market. It is used to establish the company’s strengths and weaknesses in order to contextualise them in an opportunities and threats environment, in order to define a strategic axis for internal and/or external growth. This tool has become a standard, both in institutional development mechanisms and in academic teaching. It takes as a matter of course that a territory should be likened to a competitive organisation that has to differentiate itself in a globalised market. In other words, the ends of the action are inscribed in the instrument.

2.3. Reconciling Economic, Social Justice and Environmental Issues

However, in a context of global environmental changes that have localised effects (global warming, biodiversity erosion, water stress, reduction of arable land, among others) to which states are seeking to provide a response in terms of adaptation and transition, it seems appropriate to question the framing of public policies, in particular all those instruments that struggle to integrate economic, environmental and social justice issues jointly. As a transdisciplinary approach, our approach aims to address economic, environmental and social justice dimensions together [

14,

18].

In addition to the effect of the environmental context, citizens also have deep-seated aspirations to engage in what makes it possible to respond to human needs/aspirations, social justice, solidarity, etc. As it happens, territorial public policies have a great deal of difficulty in grasping the latter, particularly because of the inadequacy of the tools used to construct these policies. In this context, the starting point of our focus is the failure of contemporary models. We are studying small, retired villages where there is no “classic” development solution and where the challenge is to restore confidence in public life as well as meaning in collective action.

Indeed, the ecological dimension of the crisis should not overshadow the social issue [

19]. It is part of it; it requires new theoretical and political frameworks, together with new ways of describing reality, in order to map out new development trajectories that are concerned with environmental justice [

18]. Environmental justice thus takes into account distributive justice (an egalitarian distribution of primary goods) but also a form of corrective justice to equalise relations between actors in their relationship with non-human living beings, what we in the West call “nature”. It calls for the participation of relatively deprived actors in their economic, cultural and sensitive relationships with nature [

20].

In other words, description and analysis methods based on the separation of nature and culture, for the sake of a market-growth logic, are proving to be inappropriate. The challenge is to define a referential of territorialised public action [

21]. In our opinion, this definition involves the creation of a particular narrative, understood as both a method and an objective of collective and participatory dynamics. The narrative mobilised in this way makes the imaginaries of rupture one of the determining elements in policymaking. For example, the narrative offers the possibility of moving away from the thinking that it is the global that generates our world. However, it is possible to think the other way around and show that the global is actually produced locally by multiple interactions [

22]. It is not an exercise in technocratic foresight but a method of situated objectivation, a process of constructing a common meaning in order to carry out actions that operationalise a collective capacity to prefigure new forms of cohabitation with all living things. It is a case of making the future collectively debatable, which presupposes the creation of spaces for collective reflection that are capable of welding common sense and imagination [

23].

2.4. Empowerment and Knowledge Circulation

The challenge is to allow each participant to express his or her singularity while laying down the conditions for a common projection towards a desirable future. It can be achieved and embodied through multiple media, according to the specificity of the contexts and the groups formed (documentaries, exhibitions, written texts, cultural practices, etc.). The objective of these narratives is, for each territory, to bring out the possibility of debating, challenging, investigating and critically participating in the future of territories in relation to each other, so that a capacity to aspire [

24] to a socially and ecologically secure and just future may emerge.

In this experiment, it is not a matter of aiming for a radical global transformation but of participating modestly, through concrete experiments, in this transformation. This role of TEC is particularly important and can be analysed through the social capital mechanisms [

25]: TEC allows for the creation of links with the outside world (for example bridging with a group of students for a project, so as to set up a market gardener).

In terms of knowledge, TEC relies on the circulation of different knowledge and cognitive resources [

26]. The aim is to encourage stakeholders’ appropriation of scholarly discourse. Our transdisciplinary approach proposes to integrate the mirror process, i.e., it is based on the researchers’ capacity to make explicit the plurality of vernacular and experiential knowledge, but also the capacity to make themselves intelligible to other actors. Language is a shared and user-friendly tool for including everyone in a common emancipation dynamic. More broadly, this circularity must be understood as a circulation at multiple levels as well as between the different levels of action. It thus takes the form of moments of questioning during which citizens bring to elected officials’ attention their multiple experiences in the field, as well as a dynamic of openness to organisational and global issues, whose visibility is not always obvious.

4. Results

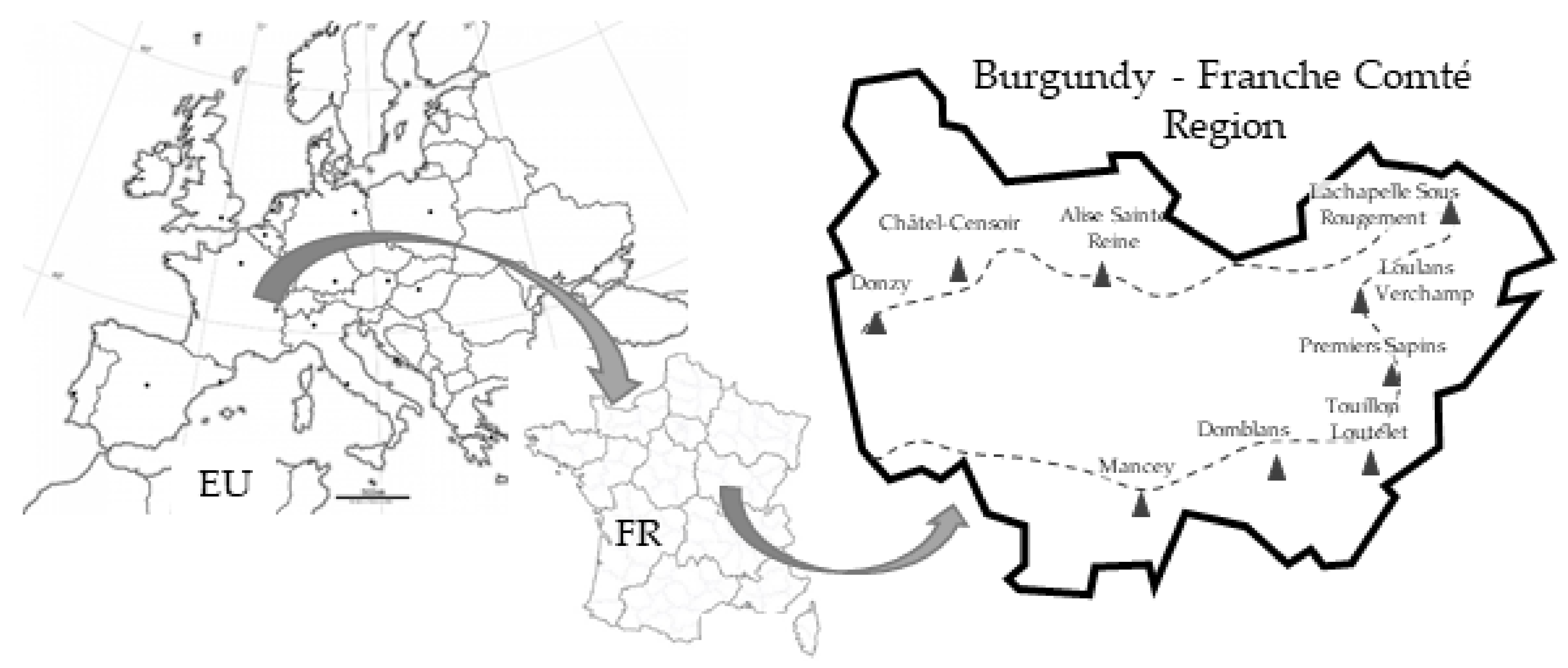

The experiment of the “Villages of the Future” makes it possible to analyse the conditions in which transdisciplinary epistemic communities (TECs) are formed and the place they occupy in local actors’ dynamics (

Section 4.1). In the nine villages involved in the experiment the constitution of these TECs may led to three different processes: the passage from a narrative to its materialisation into projects (

Section 4.2), the enlargement of the sphere of local action (

Section 4.3) and finally impacts in terms of the training of this community’s stakeholders (villagers, elected representatives, designers and scientists) (

Section 4.4).

4.1. Constitution of Transdisciplinary Epistemic Community

The constitution of the TECs and the form this network of actors takes, but also the place that it occupies in the territory’s system of actors, result from multiple factors such as the socio-economic context and the territory’s history or then again actors’ capacity to organise themselves. With reference to the four approaches to community participation proposed by Fraser [

4], we have characterised the conditions for the emergence of a TEC and the obstacles to its implementation (

Table 3).

4.2. From Storytelling to Project Implementation

The approach is mainly organised in three phases of residencies in the villages, which correspond to successive phases of immersion, projection and finally materialisation of the projects.

During the immersion period in the villages, the PMA offered a wide range of workshops to discuss everyday issues—such as schooling for the youngest, food, mobility, housing, natural resource management, soil, water, forests, or even the greying of the population, maintaining activity—and project them into the future. The underlying principle of these workshops is to organise a cognitive tension between collective exercises in imagining non-probabilistic, even utopian, futures in order to turn them into categories from which to think about the present while projecting alternative trajectories subject to the test of institutional realities (path dependence). This exercise tries to make collectively possible what is desirable, by inventing new institutional forms and rules. It differs from SWOT-type territorial diagnoses, which have been instruments for institutionalising a type of rural development based on growth and attractiveness together with global and territorial competition, little concerned for its ecological footprint.

Designers’ influence, according to the type of animation proposed, matters in that it helps in “landing” the transdisciplinary epistemic community’s proposals. It ended up taking shape thanks to the diversity of the proposed workshops. Therefore, during each several-day immersion period in villages, the designers contributed their facilitation skills to organise focus groups, commented walking and cycling tours and mock trials, during which standing and speaking in public—added to debates inherent abstraction—proved to be stumbling blocks for a number of people not very comfortable in these arenas, or who do not have the necessary time to follow the debates in their continuity. The eventful nature of participation, with its intense activities, then gave way to a long period of inactivity, which can disconcert inhabitants and elected representatives, who feel helpless once designers have left. In this temporal discontinuity, there is also discontinuity in participation forms between those that value the word, framed by ad hoc procedures and techniques, and those that value the everyday resourcefulness practised by many inhabitants, associations and the municipal council in organising waste collection along the paths, setting up a marquee for the school festival and undertaking other public activities. In these different participation forms, everyone takes part, contributes their share and receives their share. The challenge is to ensure these forms of participation complement each other in order to turn stories into tangible public action. Otherwise, the collective dynamic is liable to run out of steam among inhabitants.

In Mancey, inhabitants, organised in a village assembly, took up development and planning issues, such as waste management, the creation of short supply chains and opposition to the construction of a supermarket on arable land in the neighbouring town of Tournus. The village assembly turned these day-to-day problems into political issues that it wished to put on the municipal and inter-communal political agendas. On the strength of this participatory practice, Mancey is projecting itself into the future by promoting a social, economic and environmental dynamic that aims to keep the elderly in the village, to develop local short supply chains and a participatory third place and to develop a wetland and landscape for ecological and educational purposes, besides investing collectively in renewable energy. However, the various debates and participatory events organised with the PMA led the inhabitants, in close relation with the municipal council—which ensures the institutional link with the inter-municipal and regional levels—to deliberate in order to prioritise the actions planned over time. Indeed, the village roadmap is complicated in that it has to deal with the multi-level institutional game which, while it does not mitigate the popular political will’s power that inhabitants are keen to wield, inscribes it in the French territorial architecture based on the representative mandate and cross-financing. In other words, to land the imaginary is to take into account the temporalities and constraints of path dependency.

In Alise Ste Reine, there is an imaginary and festive ground for village mobilisation. The VDF operation aims to support the transition from a daydreamed and idealised village, which is a source of withdrawal, to the existence of concrete projects that involve the inhabitants and whose initiative is not systematically left to the local elected representatives alone. The village community here is united around a festive spirit and a shared history (the resistance of the young Celtic girl Alise against the Roman Olibrius). She has been celebrated annually for 1544 years, every last weekend in August, as part of a live show performed by the villagers, down generations. Valuing this historical attachment as well as this festive and playful state of mind, PMA artists spent a week in the village, taking the time to visit all the families (leaflets distributed in all the letterboxes, direct contacts in the village streets, meeting in the homes, sharing convivial moments...). A trailer played by the villagers was first produced to promote an initial citizens’ assembly at the end of July 2021. It brought together 45 inhabitants around a participative stage production. The idea was to raise awareness of the need to integrate social and environmental issues into the village and to counter an idealised status quo around the idea of comfortable living. By staging two tourists who arrive in Alise and question the audience on various subjects, the PMA accompanied participants to question both tourists on different subjects: global warming and consequences on the surrounding forest, water resources and agricultural production; food and eating habits; modes of transport; waste management; equality between men and women; or even children’s rights and support for the elderly.) It was thereby possible to identify several topics, which were then submitted to the inhabitants’ vote (online or by post). Six themes were then selected (multi-sport ground; vegetation and the environment; development of public space; urban planning and heritage; welcoming tourists, festive and artistic events). These themes were worked over one weekend at the end of November 2021. One Sunday morning, 35 people worked in workshops on these 6 topics, so as to translate them into 2 or 3 concrete projects, specifying a timetable, methods of action, etc. After sharing a meal, a citizens’ assembly—organised in the municipal hall, in which the PMA architects had set up a mobile amphitheatre—enabled each workshop representative to present their projects in an argumentative manner. Debates, abiding by the rules of fair public-speaking, enabled group projects (multisport ground and public square) framed into 6 proposals, to be carried out in Alise. A vote (each participant had 10 peanuts to be divided among 6 jars corresponding to 6 projects) then allowed these projects to be ranked. The two projects deemed as priorities (developing a public square and organising a Spring festival to exchange seeds and welcome newcomers) were then presented more widely by the Town Hall to the whole village, so as to gather additional opinions via the local bulletin. They are currently being put into practice.

These two examples should not obscure the difficulties in implementing VDF projects. For example, in Châtel-Censoir, the municipality is managed by a new team. Its legitimacy is based on its mandate programme, because it has been elaborated with the mobilisation of a part of the population eager for change. However, it proved to be reluctant to reopen local mobilisation within the framework of the activities proposed by the PMA. The reason is they dreaded opposition motions to the projects, put forward by the new team, led by newcomers who had been living in the municipality for less than 10 years. The programming of workshops to mobilise residents by the PMA proved difficult to plan with the municipal team. The two workshops that were organised did not reach many residents outside the municipal team, even though the provision of a suggestion box made it possible to collect contributions from residents, indicating their curiosity about an approach that seeks to express their needs and expectations for the future.

4.3. A Broadening of the Sphere of Analysis and Action

In almost all the villages studied, the question arose of avoiding a club effect limited to the municipal team and a few small local groups that are organised and well-endowed culturally and socially. The challenge is to establish the symmetry of relations in the co-production of a narrative that takes into account the multiplicity of representations, relationships and interests in the places that can reconcile the diversity of the inhabitants’ expectations and projections. The point is to take into account the plurality of life experiences in the villages. Moreover, collectively guarding against the club effect is not just a case of the participating population’s size, even though this plays an important role in the organisation of the participation methods. Considering the breadth and depth of participation is an essential procedural element for the proper functioning of each village’s transdisciplinary epistemic community. The breadth of participation answers the following question: Who participates in the development of the narrative—researchers, sponsors, representatives of the beneficiaries of the studied device, indirect beneficiaries, citizens and their representatives, or then again opponents? The depth of participation answers the following question: How often are participants involved in the development of the narrative and at what stages (definition of the situation, problematisation, construction of the storytelling methods and techniques, workshops facilitation, data collection, restitution…)? Thus, finding a local agreement on the procedures for developing the narrative warrants against the experiment getting confiscated.

For example, in Mancey, “the young people of the village” are invited to post drawings, photos and videos on Instagram to imagine specific emblematic places in their daily lives in 15 years’ time. The use of social networks to mobilise young people, who are not very inclined to take part in meetings organised in the town hall by older people, makes it possible to increase the size of the participating population. However, taking into account these adolescent imaginations is a challenge in terms of participation depth, which is yet to materialise in the planned developments. The same applies to people’s mobilisation in social insecurity situations (food, health, energy, employment, old age…). These small villages do not always enjoy the associations or social services that allow access to these populations living on the fringes of the better endowed groups and individuals and foster spontaneous participation in the meetings organised by the PMAs. This is one of the reasons why considering participation as an exercise open to all forms of life experience is a challenge in this experiment.

In Alise Ste Reine, exchanges between inhabitants (who were looking to set up a vegetable garden) and the Living Lab researchers made it possible to build bridges between a village association and the agronomy school in the nearby university town. A group of students will thus be involved in this project. Similarly, with a view to the March 2022 spring festival, links have been established between this association’s members and an ecology researcher, designed to enhance local seeds and preserve rare plant genetic resources. These initiatives were taken without municipality involvement, encouraging villagers to become directly committed to local public action.

4.4. Impacts in Terms of Stakeholder Training: From Living Lab to Learning Lab

From the outset, the VDF experimentation was based on seeking new ways of thinking and achieving a form of rural development that could suspend the top-down and technocratic logic in favour of inhabitants’ expression of needs and projections. The specificity of this initiative is to create the necessary conditions for some people to get trained into public actors, understood as an intermediary body between the local population and its governors. Thus, groups of inhabitants, associations, PMA, regional services, municipal and inter-municipal elected officials, besides researchers, make up a transdisciplinary epistemic community to enable inhabitants, through their knowledge and life experiences, to map out alternative future trajectories. Beyond the technical animation skills exchanged among stakeholders to constitute a cooperative public action repertoire, what emerges is that it is an issue of redefining postures, particularly for elected officials and regional services. For the elected representatives, it is a question of how to reconcile the representative mandate and an organised population’s participation, capable of thinking and projecting collectively, and for regional services, which have to get rid of the technocratic logic.

The various stakeholders found it challenging to identify what learning was underway. It was an exercise of collective reflexivity which required an exteriority to a game to be created in which each one takes part. Learning this reflexive posture was a collective stake of primary importance in the experimentation.

In Premiers Sapins, for example, this new commune seeks to create a local life community from the 6 villages that initially made it up. The objective is to learn how to live together and create a common sense of belonging. Through the activities proposed, the VDF operation, in a very progressive way, maintains, shapes or reactivates links between inhabitants, becoming an inter-knowledge vector. For example, a festive evening gathering 60 people of all generations, dedicated to the projection of a film featuring the testimonies of these 6 villages’ elders, made it possible to reveal the existence of a community of experiences, even though local rancour is regularly bemoaned. The PMA took advantage of that evening to propose a work café around four themes: identification of places of exchange based on a map; expression of ideas for encounters, thanks to the creation of a frieze of characters; enhancement of the commune’s sensitive areas (including a remarkable natural site, “La Roche de Hautepierre”), and finally, a collection of ideas on the use of “La Distillerie” (a solidarity bar). In a friendly atmosphere and around a common history (the elders’ Second World War memories, testimonies on ancestral agricultural, craft and forestry practices), these exchanges allowed genuine inter-generational decompartmentalisation while breaking local differences between villagers.

In Mancey, the village assembly is in direct opposition to the urban planning methods devised on an intermunicipal scale. In fact, the inter-municipal political power has entrusted the technical mission of territorial planning to a private company that thinks of the future of the villagers while ignoring local experiences at the village level. For the village assembly, the technical nature of urban planning is a hindrance to its involvement in this exercise, which will condition the future of the village. The challenge is therefore to translate the technical issue of inter-municipal planning into a political issue of municipal sovereignty over land management. It was during the workshops proposed by the PMA and the region’s services that this change of perspective was constructed. It enabled the village assembly to join forces with the municipal council to find a political and institutional entry point into the urban planning exercise, not in an advisory capacity, but in terms of expertise in the use of the territory, which is now recognised by stakeholders as a democratic experience: democratic, not in the sense of representative democracy (aggregation of votes mobilised by the majority vote) or of a particular form of government, but democratic because it takes into account the life experiences, attachments to places and various forms of inhabiting a territory that define, question and construct the reality on which inhabitants (individually or collectively), elected representatives, users, associations and companies want to act on the scale of the territory they live in. Bringing this democratic experience into the institutional frameworks of urban planning is a quiet change, but one that opens up a breach in the way we project the territory into a desirable future.

Thus, by structuring itself into a village assembly, a large part of the village population’s collective capability to describe its living areas institutes new forms of participation in order to legitimise them and place them on the new municipality’s political agenda. The ability to connect them to larger institutional scales is closely linked to the engineering system set up by the region and project management companies, which broadens the cognitive, technical and institutional resources available to the committed inhabitants. The PMA’s immersion in the heart of the village and its population, the organisation of debates in the four hamlets, in inhabitants’ homes, in the town hall, and cycling and walking visits to the villages, has enabled new people to be enrolled, thus counteracting the club effect that is characteristic of many participatory dynamics.

In Alise Ste Reine, the preparation of public meetings and inhabitants’ participation in the two citizens’ assemblies made it possible to create situations for learning about citizenship, by pointing out the importance of taking charge of issues and translating them into concrete actions (making proposals that integrate inhabitants’ needs and desires for the development of a public square, preceding a meeting with architects and landscapers). The group of children, who were intensely involved, were able to realise the point of a public square’s multi-purpose character. Exchanges with the other villagers enabled them to move from the idea of a skateboard park to a multi-purpose public square.

5. Discussion

The results of this VDF experiment, centred around 4 main villages, are globally encouraging in terms of thinking about rural development differently from pre-conceived, standardised diagnoses based on a prevailing growth objective. They confirm the possibility and value of creating transdisciplinary epistemic communities (TECs), while pointing out the sine qua non difficulties and conditions for their existence. Thus, while in both Mancey and Alise villages—thanks to an anteriority of active citizenship (Mancey) or shared values (Alise)—a TEC is being set up, the reality is still under construction in Premiers Sapins. Finally, we regret to say the village of Chatel-Censoir has hit a dead end.

The first issue to be raised in this discussion is the need to reason about the interrelationship between the results presented in the previous section. Analysing such an experiment is indeed a difficult exercise because it is based on a multitude of interdependent elements that are difficult to isolate for generalisation. For example, the symmetrisation of relations between stakeholders is essential to the constitution of a transdisciplinary epistemic community, whose size is a methodological and division of labour issue. Indeed, dialogue and the symmetry of relations become more difficult to cope with as the number of participants increases. There could even be a limit to the size of the workforce for co-constructed projects, and therefore, controlling the breadth of participation is a key issue. This would mean these projects cannot be scaled up [

30] because they are based on an inescapable relational dimension. Increasing the workforce size means escalating the quantity and diversity of the relationships, which could generate changes in the way the experiment is conducted and make the method and results difficult to reproduce on a larger scale.

In fine, this type of experimentation is not scalable [

31], i.e., it cannot be expanded without rethinking its basic elements, in particular the intuitu personae character of this type of collective action. Scalability is only possible if the elements of the project do not form transformative relationships that could change it as elements are added. People involved in transdisciplinary epistemic communities need to be fully aware of what they are trying to achieve. If it is a case of training citizens, in a logic of emancipatory popular education, to make them a lever for rural development new forms and practices, it seems coherent to generalise knowledge and practices by means of the scaling-out method, rather than deploy large-scale projects, which seems to inevitably produce a hierarchical division of public action. In other words, with scaling-out as a generalisation process, it is possible to promote local environmental agency, i.e., exercise the freedoms by which a group or community collectively seeks to achieve an objective that goes beyond members’ individual interests [

16].

That is why generalisation is therefore possible on the basis of the conditions of agency, and not on the basis of locally set objectives that remain inarticulable with distant and global issues. Accepting the difficulty of articulating the different scales of projects that jostle and compete with each other means considering that localised collective action based on trust, learning effects and reciprocal adjustments cannot always be reproduced on the same scale, let alone a larger one. The change of scale would imply redefining the structure and dynamics of the organisation of collective action. However, the issue of generalising remains salient. It could find an answer in a translocal relational dynamic. Ensuring translocal networking might lead to opening up the populations and skills mobilised here to the experiences lived there. It is on this condition, whose modalities are still being worked out, that the regional generalisation of this experimentation could be implemented on a regional scale. In any case, from an academic point of view, they are an avenue of investigation for further refining the activity of “sustainability brokering” [

1].

Furthermore, flexible connectivity does facilitate the multiscalar and transsectoral integration of collectives, thanks to the capacity to adapt to contextual changes and to integrate disjointed themes. Such a configuration opens up new descriptions of reality by decompartmentalising the different local initiatives, integrating marginalised social groups and taking into consideration the three pillars of the ecological transition from the outset.

Finally, the limits of the experiment are due to the difficulty of projecting into the future and consequently regarding the contribution to the narrative of a sustainable village trajectory. “Why invite and use the unfathomable, open future? Why not just improve the models that rely on the past to think about the future, keep discovering more and more data that can only come from the past, and produce more and more detailed and comprehensive plans on how to better colonise the future? And in particular (to use the current rhetoric of ‘global transformation’), when we are ‘threatened’ by uncertainty, why not give in to the temptation to reassure ourselves by making only ‘evidence-based’ choices that depend on knowing what has worked well in the past and what will work in the future?” It is in these terms that Riel Miller invites uncertainty and non-probabilistic futures as categories from which to think about the present and project possible bifurcations in development trajectories [32], p. 129.

Operationalising this invitation to rupture in the fabrication of transition narratives and imaginaries is more a matter of cobbling bits and pieces together rather than a systematic, standardised method. It presupposes a form of pragmatic radicality, i.e., a collective action attached to strong principles—environmental justice, local environmental agentivity, emancipatory politics—which at times works jointly with institutions, and at other times opposes them. Such pragmatic radicality can be found in the various participatory workshops offered to stakeholders in the “Villages of the Future” experiment, to varying degrees.

The next step is precisely to continue observing and accompanying this valorisation of pragmatic radicality situations into concrete actions that bring about sustainable rural development.