“We Beat Them to Help Them Push”: Midwives’ Perceptions on Obstetric Violence in the Ashante and Western Regions of Ghana

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Design

2.2. Study Participants and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

2.4. Data Management and Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

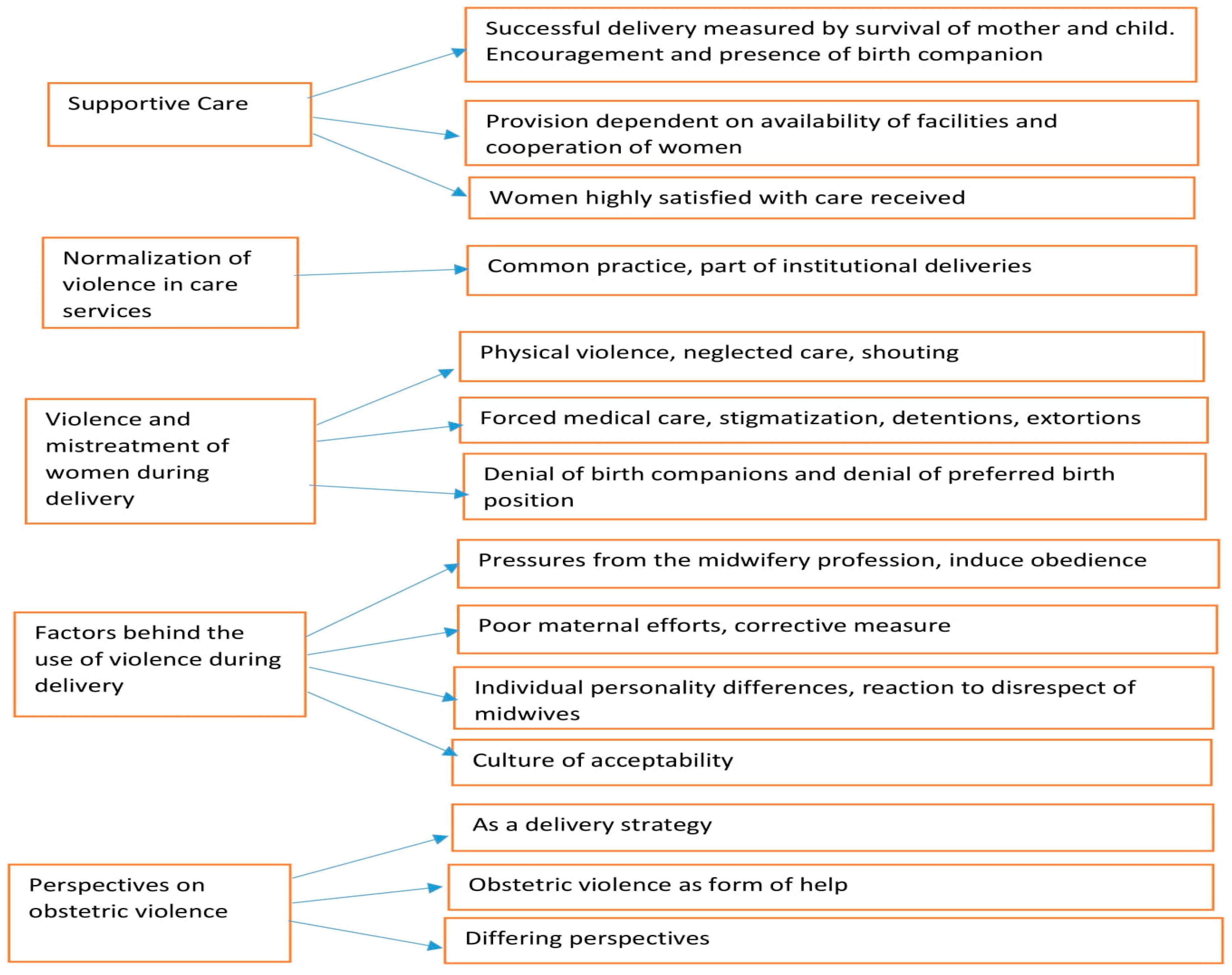

3. Results

3.1. Supportive Care

Supportive care is taking care of the mother, delivering them and the baby being alive, and the mother too being saved. Yes, skillfully. (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

Supportive care for me is like giving women information concerning the delivery or maybe if there is time you give her a sacral massage. You can engage her in a conversation which is a kind of diversional therapy. (Midwife, Ejura District Hospital, Rural)

We have a standard mode of practice. We create rapport with the client, we provide antenatal care, and we ensure privacy during delivery and explain findings to the client. So, we are providing supportive care. (Midwife, Kwesimintsim Polyclinic, Urban)

I think that depends on the patient because there’ve been so many instances where some patients exaggerate their symptoms and so we don’t waste so much time on such cases. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

If we have the logistics, yes, but if the logistics are not there, sometimes you know what to do for the client but what you will need to do it, you don’t have it. If the logistics are there, yes, services are provided satisfactorily. But if there are no logistics, which is usually the case, definitely, the person will not get a satisfactory service. But I believe that we do give them a very good service. (Midwife, Ejura District Hospital, Rural)

Oh very good! That one is exceptional. 80% satisfaction. In this hospital, we are baby and mother-friendly, which is why it used to be called the children’s hospital. Women are satisfied with the care they receive which is why we have so many clients that visit this particular hospital. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

Anytime I come on duty I go around to ask the mothers how they were treated and if any midwife behaved rudely in my absence and I don’t get any negative feedback. So, we treat them well. (Midwife, Kwesimintsim Polyclinic, Urban)

3.2. Normalization of Violence in Care Services

Severally, sometimes here we even beat the client when they are in labor, during labor, it is normal to do that because the baby’s head has come, and instead of the client pushing, she will be relaxing, and the baby too will be asphyxiated. So, unless you beat the client’s thighs, the baby might die. Some become relaxed, they think you the midwife should pull it for them. So, during labor, we do that. (Midwife, Agona Nkwanta Health Centre, Rural)

Oh, the shouting is normal and necessary, but we don’t insult them. (Midwife, Kwesimintsim Polyclinic, Urban)

It is normal. There are some women, they like to make noise and shout, those people, we are hard on them not because of anything but because of their well-being. So, for the shouting at clients, it can’t stop. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

I’ve witnessed such incidence, not in this hospital but in other settings because they (women) can’t endure pain, they also misbehave. (Midwife, Ejura District Hospital, Rural)

It is common, but we can’t go away with it anymore because nowadays people are getting educated and legal issues can arise. Everybody is advising herself, so, if you are a midwife, you should also advise yourself not to get in trouble with those things. (Midwife, Nkenkaasu Government Hospital, Rural)

There is a law about negligence. When you come to the hospital and feel that you have been abused in any way, you can go to court and then sue the midwife. Sometimes, they can even take the midwife’s license, so she won’t be able to work as a midwife in Ghana. A lot of people do that now. Right now, we are being careful. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

3.3. Violence and Mistreatment of Women during Delivery

3.3.1. Physical Violence

Sometimes we even tie them to their beds. That one, too, is there. When their blood pressure rises, they have eclampsia and they become aggressive, so we tie them. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

One of our colleagues was having challenges with a laboring woman, and when we went, the client complained to us that the midwife did this and that, but it was not true. Then, we now saw the head of the baby was there and the client was not pushing, so we decided to give a little pain so that she will push out of the pain. We hit her but it was not intentional to cause harm. (Midwife, Nkenkaasu Government Hospital, Rural)

Some women don’t put so much effort when they are asked to push because of the pain they feel, so the midwives have to cause them pain sometimes by blocking their nostrils, so they would know how the baby feels as a result of their low effort in pushing. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

3.3.2. Neglect

We ignore clients based on their reactions. Maybe when we review clients and it’s just 1 cm dilatation, but the client is insisting the baby is coming. And you do the vaginal examination again and it’s still 1 cm and she would be shouting and crying and making a whole lot of fuss. Most often we ignore such people. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

Last two weeks, I was right here writing. A woman was brought in just like this one was brought in. I asked her to lie down, and I did all I could, but she did not mind so I just ignored her. Later I heard someone scream, I turned around and saw her standing there. She was pushing the baby out and I didn’t mind her. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

3.3.3. Shouting

As for the shouting, we have shouted at them. If you don’t shout at them, you will end up writing a death note because of their negligence. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

Usually, it’s just shouting in this hospital, but I’ve witnessed incidences of midwives hitting pregnant women in labor because they wanted them to push. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

We don’t normally beat them, but shouting, yes. For some clients, you will talk to them politely and they will still misbehave, we are all humans, so we shout at them. (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

3.3.4. Failure to Seek Consent for Medical Intervention and Stigmatization

We inform them. Especially those who have not delivered before. For them, their perineum is very tight, so before delivery, we tell them because they haven’t delivered before, we might give them a cut (episiotomy). So, we tell them beforehand. (Midwife, Agona Nkwanta Health Centre, Rural)

Whatever we do, we tell them. During the delivery point, we have to do what is best, so, when we are cutting (episiotomy), we tell them and comfort them when they are feeling the pain. We also tell them we have to stitch the place so that it will go back to normal. (Midwife, Kwesimintsim Polyclinic, Urban)

In cases where the woman does not agree, we use our discretion, because we have knowledge in childbirth more than the woman and so we know what’s best to do so we just go ahead and do it. (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

For instance, for HIV patients, when they come to the hospital, some of the nurses and midwives are too careful with them and this makes them feel awkward and rejected. But that is when the person needs us more to talk and counsel her and let her know about the procedures she will go through so that her child will not be infected. However, some healthcare professionals will rather be rejecting the person. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

3.3.5. Detention and Extortion

Detention happens, yes, for cesarean sections because it is costly. So, if they do not pay their bills they will not be discharged. (Midwife, Kwesimintsim polyclinic, Urban)

We have detained several women, they will be here until they settle their bills. They can’t go. They can go and settle the bills they owe the hospital but still, we have a reason why we are keeping them here and no one can come and tell us otherwise. They bought something from us and they are supposed to pay but they did not. Sometimes, we seize their ANC cards before releasing them. Because this new card has the medical information of the babies which they will need for subsequent checkups. So, when they come, they will be asked to pay before it is released. (Midwife, Nkenkaasu Government Hospital, Rural)

Some of the midwives behave as if they have a monetary target when they come to work. They want to benefit from every delivery by taking money from the client. At the end of the month, they will still take their salary. Usually, if you treat the client well and they are leaving they can say take this ₵10 but some nurses demand from the client and they termed it “egg money”, egg money for what? The client is supposed to give to you from her heart, but not that you demand it. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

3.3.6. Denial of Birth Companions and Preferred Birth Position

In labor, we don’t allow birth companions because we don’t want another person to be exposed. If we had private wards, we would have allowed it. In labor women sometimes expose themselves and if we allow birth companions, someone’s husband will be standing by his wife and will be looking at another woman’s nakedness, it’s not nice. (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

Mostly we don’t allow them to be there because most of the women when they see their husbands they misbehave. Like maybe assuming there is no contraction or the contraction comes and goes, the moment the woman sees the husband she begins to shout “daddy I’m tired, I want to do CS” and so on, so mostly we don’t allow them to go there. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

The women cannot choose which position they want to deliver, no. We tell them to lie in the lithotomy position. The squatting position is distressing and stressful for us although I learned that it is easier for women to deliver squatting than the lithotomy. (Midwife, Dixcove Government Hospital, Rural)

They’re allowed to deliver in only one position. The women here are made to deliver in the lithotomy position. (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

3.4. Factors behind the Use of Violence during Delivery

3.4.1. Pressures from the Midwifery Profession

Sometimes out of frustration some midwives shout at the client because as per our practice there is something known as auditing, that is when you would be called to answer questions when either a baby or a mother dies during delivery. So sometimes the midwives would want to avoid that. Although is not good but she has to save the mother and the baby to avoid auditing. (Midwife, Dixcove Government Hospital, Rural)

As for the shouting, it will not end. Because if the client is misbehaving and you don’t shout at them and there is a fetal death you will go for an audit about it, and your certificate will be at risk. So that time you are doing everything possible so that the client will not put you in trouble. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

There are laws governing these cases because if a midwife becomes the reason for the loss of either the mother or baby; She’ll have to face the law. She might even lose her license to ever practice as a midwife. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

I think it’s because of the stress we go through to care for all the patients. Also, I think it’s because we lack the basic things we need to work with. Sometimes it’s a transfer of anger from the problems we face. (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

Sometimes the drugs are not available, so we can’t give them the drug to numb the area where we’ll have to suture after episiotomy. So, they feel pain when the suture needle touches their skin. (Midwife, Ejura District Hospital, Rural)

3.4.2. Inducing Obedience

It happens because some of them don’t comply with the things we tell them not to do. There are some women when you shout once then they become sturdy. (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

When it gets to a point and we don’t apply those things, we don’t know what will happen. If you hit and shout at the person, it will put some kind of fear in the person to push. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

3.4.3. Poor Maternal Effort

Some women too have poor maternal efforts so unless you shout at her, she will be relaxing. Maybe she is in labor but her mind is elsewhere so when you shout at her she will focus. All these are done to improve the quality of child delivery in hospitals. I wouldn’t be happy if my patient loses her life or that of her baby. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

Some women when you tell them to push, they will be relaxing, and the baby too will be asphyxiated, so unless you beat the client they won’t push. If they don’t push too the baby might die. Some become relaxed they think you the midwife should pull it for them. So, during labor, we use to do that (beat them). (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

3.4.4. As a Corrective Measure

When the person is in labor sometimes if the person is doing something that will cause harm to herself and the child, we will shout at her. (Midwife, Nkenkaasu Government Hospital, Rural)

Sometimes the women fail to comply with all we ask them to do. For instance, we educate them on how they’ll feel when they have contractions and ask them to lie on their left side or try to breathe through their mouth whenever they experience the pain but some of them get aggressive and try to do things they’re not supposed to do because of the intensity of pain they feel. When the midwives try to correct her and make her understand why she wasn’t supposed to do that, they misinterpret it as maltreatment, they think we’re maltreating them. After a successful delivery, they tell their families a different story to make them think we maltreat them. (Midwife, Dixcove Government Hospital, Rural)

3.4.5. Individual Personality Factors

Individual differences count, some midwives are like that. They will shout at the patient over the slightest thing. But if you are calm with the patients and talk to them, they are cooperative. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

I think that individual differences also contribute—a person’s character. For some clients, you will have to force them because most of them can’t handle pain. Some people will just feel reluctant to push and if you don’t do that you will end up losing the baby or both. (Midwife, Essikado Government Hospital, Urban)

Some patients can be very annoying. They will come to labor and the things they will do will make you shout at them. Some patients come here and sleep on the floor. Somebody too will intentionally deliver on the floor. Imagine if care is not taken and the baby’s head hit the floor, she will be the one to blame you. So, I don’t think it’s intentional that they are shouted upon, it’s their own fault. Their behavior will make you shout at them. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

3.4.6. Obstetric Violence as a Reaction to Disrespect

There was a time when one woman came to the hospital for delivery, she kept defecating on the floor of the labor ward and so in such a case, the midwives would be upset. Some women even say it’s our job to clean up after them. (Midwife, Dixcove Government Hospital, Rural)

Women themselves push you to do those things. One day come and work with us and you see that midwives are doing very well. The things that they do, they will throw their pad on the floor, they will be touching you, vomiting around. Some people too their relatives will come and curse. They will come and be dictating to you and all sorts of things. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

3.4.7. Culture of Acceptability of Violence

A woman who showed no effort to push was beaten and this made her push. And after she delivered her baby, she apologized to the midwife for all she did and even thanked the midwife for slapping her thighs when she didn’t want to push. She said had it not been for the slaps she wouldn’t be compelled to push hard enough. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

3.5. Perspectives on Obstetric Violence

3.5.1. Obstetric Violence as a Delivery Strategy

Some clients have been over-pampered at home so when it’s time for them to push they will be telling you that they are tired. At that time, you have to hit the person just to let the person know that they are not in their comfort zone. Even some people faint during delivery so when you are hitting the person, she will be conscious. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

If the person is fully dilated, and the person doesn’t push the baby can die or the mother can end up with a C-section. The first thing I will do is either I will shout or I will beat your thighs, if you don’t push, I will give you an episiotomy. I will cut your vagina but that one they are afraid, if you take the scissors and they see it they suddenly get the energy to push. You will think I am abusing the client because I am stepping on the client’s rights. But to me, I am doing the right thing. So, these are some of the abuses when I am caught, I can defend it and it is acceptable because in the end I will end up successfully with the baby and the mother all doing well. (Midwife, Nkenkaasu Government Hospital, Rural)

We don’t shout to show disrespect, we are saving the baby’s life. The labor ward is between life and death. And at that time, when the baby is coming, the baby does not get blood oxygen supply from the mother again., So when it is time for you to push and you relax, you are decreasing the oxygen supply to the baby and if care is not taken the baby can die. I have to shout at you to be on track that you are delivering, you should push till the baby comes out, that’s why we shout. (Midwife, Agona Nkwanta Health Centre, Rural)

It is not good but there is no option because if the baby dies during that process, she will say it’s the midwife that killed the baby. (Midwife, Dixcove Government Hospital, Rural)

3.5.2. Obstetric Violence as a Form of Help

Oh, I don’t think that is bad in itself, we shout at them just to help them. They mostly do not cooperate when they are in labor because of the pain. (Midwife, Dixcove Government Hospital, Rural)

It has a positive side, if we have to shout to save a client it is a positive thing. (Midwife, Dixcove Government Hospital, Rural)

If a midwife shouts at you for your baby to come and you don’t want but you want to lay down for her to pamper you to lose your baby, then it is your fault. Next time you will wish she shouts at you for you to get your baby. We do that to save the baby. Pampering them gives a lot of complications. (Midwife, Nkenkaasu Government Hospital, Rural)

I do not think it is mistreatment; it helps them to push in order not to lose their babies. A midwife must exhaust all means to get the needed results so with that, they will shout at you and that is good for the client. (Midwife, Dixcove Government Hospital, Rural)

3.5.3. Differing Interpretation of Abuse

Imagine all the beds being full and one person who is not having contractions or progressing will be complaining about the pain and giving a false alarm. That one the client will be ignored, you get me. But if the contraction is there and 4 h have elapsed and the client is not attended to, it means the client has been ignored and that’s our negligence. So, when the time is due and we don’t attend to the person that is an abuse. (Midwife, Maternal and Child Hospital, Urban)

They will say I am physically abusing them. But for a midwife, my expectation is to help the mother and the baby to be alive. We don’t have the mission or vision to lose a baby. So, if you are at the second stage of labor, and you misbehave I need to put in actions, one of my actions is either, I will shout, “madam, push because the place your child’s head is it’s not good”. Some I need to go to the extent of beating the client, for the client to know that in fact I am aggressive. They will think I am abusing them, but to me, in the end, I will be successful because in the end the baby and the mother will be alive. Their source of abuse differs, some clients will say they were abused, but when you come to my side, it is not an abuse, I am being aggressive for me to end up successfully. (Midwife, Ejura District Hospital, Rural)

It is inhumane. You can’t be beating someone who hasn’t done anything to you. I think it’s better you talk to the person than beat the person because you don’t know why the client is doing that. Sometimes some of them just need a little pampering so you don’t have to be harsh on the client. (Midwife, Nkenkaasu Government Hospital, Rural)

I feel sad because inflicting pain on a woman who is already in pain is really not cool. I’ve personally not maltreated any pregnant woman but like I said it’s due to the differences in personality that makes some midwives do that. (Midwife, Tafo Government Hospital, Urban)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/327595/9789241516488-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Negero, M.G.; Mitike, Y.B.; Worku, A.G.; Abota, T.L. Skilled delivery service utilization and its association with the establishment of Women’s Health Development Army in Yeky district, South West Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Making Pregnancy Safer: The Critical Role of the Skilled Attendant: Joint Statement of WHO, ICM and FIGO, WHO, ICM, FIGO.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42955/924?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Gao, Y.; Barclay, L.; Kildea, S.; Hao, M.; Belton, S. Barriers to increasing hospital birth rates in rural Shanxi Province, China. Reprod. Health Matters 2010, 18, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odonkor, S.T.; Frimpong, C.; Duncan, E.; Odonkor, C. Trends in patients’ overall satisfaction with healthcare delivery in Accra, Ghana. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghana Health Service. 2016 Annual Report. Ghana: Ghana Health Service. 2017. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2016-Annual-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Tuglo, L.S.; Agbadja, C.; Bruku, C.S.; Kumordzi, V.; Tuglo, J.D.; Asaaba, L.A.; Agyei, M.; Boakye, C.; Sakre, S.M.; Lu, Q. The Association Between Pregnancy-Related Factors and Health Status Before and After Childbirth with Satisfaction with Skilled Delivery in Multiple Dimensions Among Postpartum Mothers in the Akatsi South District, Ghana. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 779404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameyaw, E.K.; Dickson, K.S.; Adde, K.S. Are Ghanaian women meeting the WHO recommended maternal healthcare (MCH) utilisation? Evidence from a national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS); Ghana Health Service (GHS); ICF. Ghana Maternal Health Survey 2017: Key Findings. 2018. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR251/SR251.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Krug, E.G.; Mercy, J.A.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Zwi, A.B. World Report on Violence and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42495 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.; Hunter, E.; Lutsiv, O.; Makh, S.K.; Souza, J.P.; Aguiar, C.; Coneglian, F.S.; Diniz, A.L.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowser, D.; Hill, K. Exploring Evidence for Disrespect and Abuse in Facility-Based Childbirth Report of a Landscape Analysis; Harvard School of Public Health University Research Co, LLC: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://cdn2.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2014/05/Exploring-Evidence-RMC_Bowser_rep_2010.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Chadwick, R.J. Obstetric violence in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 106, 423–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Georgio, P. Obstetric Violence: A new legal term introduced in Venezuela. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010, 111, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Prevention and Elimination of Disrespect and Abuse during Facility-Based Childbirth: WHO Statement. 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/134588v (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Maya, E.T.; Adu-Bonsaffoh, K.; Dako-Gyeke, P.; Badzi, C.; Vogel, J.P.; A Bohren, M.; Adanu, R. Women’s perspectives of mistreatment during childbirth at health facilities in Ghana: Findings from a qualitative study. Reprod. Health Matters 2018, 26, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Hunter, E.C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.M.; Souza, J.P.; Vogel, J.P.; Gülmezoglu, A.M. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod. Health 2014, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremichael, M.W.; Worku, A.; Medhanyie, A.A.; Edin, K.; Berhane, Y. Women suffer more from disrespectful and abusive care than from the labour pain itself: A qualitative study from Women’s perspective. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, A.; Dey, A.; Boyce, S.; Seth, A.; Bora, S.; Chandurkar, D.; Hay, K.; Singh, K.; Das, A.K.; Chakraverty, A.; et al. Associations between mistreatment by a provider during childbirth and maternal health complications in Uttar Pradesh, India. Matern. Child Health J. 2017, 21, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darilek, U.A. Woman’s Right to Dignified Respectful Healthcare During Childbirth: A review of the literature on Obstetric Mistreatment. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 39, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.; Sharman, R.; Inglis, C. Women’s descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.; Klein, K.; Vasquez, P.; Williams, C.R.; Gibbons, L.; Cormick, G.; Belizan, M. Observations and reports of incidents of how birthing persons are treated during childbirth in two public facilities in Argentina. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 158, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, R.; Frías, S. Obstetric Violence in Mexico: Results From a 2016 National Household Survey. Violence Against Women 2019, 26, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedam, S.; Council, T.G.-U.S.; Stoll, K.; Taiwo, T.K.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; McLemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers Study: Inequity and Mistreatment during Pregnancy and Childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Mehrtash, H.; Fawole, B.; Maung, T.M.; Balde, M.D.; Maya, E.; Thwin, S.S.; Aderoba, A.K.; Vogel, J.P.; Irinyenikan, T.A.; et al. How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: A cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys. Lancet 2019, 394, 1750–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganle, J.K.; Krampah, E. Mistreatment of Women in Health Facilities by Midwives during Childbirth in Ghana: Prevalence and Associated Factors. In Selected Topics in Midwifery Care; Mivšek, A.P., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alatinga, K.A.; Affah, J.; Abiiro, G.A. Why do women attend antenatal care but give birth at home? A qualitative study in a rural Ghanaian District. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C.A.; Adongo, P.B.; Aborigo, R.A.; Hodgson, A.; Engmann, C.M. ‘They treat you like you are not a human being’: Maltreatment during labour and delivery in rural northern Ghana. Midwifery 2014, 30, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crissman, H.P.; E Engmann, C.; Adanu, R.M.; Nimako, D.; Crespo, K.; A Moyer, C. Shifting norms: Pregnant women’s perspectives on skilled birth attendance and facility-based delivery in rural Ghana. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2013, 17, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adu-Bonsaffoh, K.; Tamma, E.; Maya, E.; Vogel, J.P.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Bohren, M.A. Health workers’ and hospital administrators’ perspectives on mistreatment of women during facility-based childbirth: A multicenter qualitative study in Ghana. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzomeku, V.M.; Mensah, A.B.B.; Nakua, E.K.; Agbadi, P.; Lori, J.R.; Donkor, P. “I wouldn’t have hit you, but you would have killed your baby:” exploring midwives’ perspectives on disrespect and abusive Care in Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghana Statistical Service. Population and Housing Census. 2021. Available online: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/storage/img/infobank/2021%20PHC%20Provisional%20Results%20Press%20Release.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: Riverside, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayra, K.; Matthews, Z.; Padmadas, S.S. Why do some health care providers disrespect and abuse women during childbirth in India? Women Birth 2021, 35, e49–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maung, T.M.; Mon, N.O.; Mehrtash, H.; Bonsaffoh, K.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Aderoba, A.K.; Irinyenikan, T.A.; Balde, M.D.; Pattanittum, P.; Tuncalp, Ö.; et al. Women’s experiences of mistreatment during childbirth and their satisfaction with care: Findings from a multicountry community-based study in four countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 5, e003688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivers, N.; Jamtvedt, G.; Flottorp, S.; Young, J.M.; Odgaard-Jensen, J.; French, S.; O’Brien, M.A.; Johansen, M.; Grimshaw, J.; Oxman, A.D. Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 6, CD000259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; I Avan, B.; Rajbangshi, P.; Bhattacharyya, S. Determinants of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care: A review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balde, M.D.; Diallo, B.A.; Bangoura, A.; Sall, O.; Soumah, A.M.; Vogel, J.P.; Bohren, M.A. Perceptions and experiences of the mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities in Guinea: A qualitative study with women and service providers. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Fawole, B.; Titiloye, M.A.; Olutayo, A.O.; Ogunlade, M.; Oyeniran, A.A.; Osunsan, O.R.; Metiboba, L.; et al. Mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria: A qualitative study on perceptions and experiences of women and healthcare providers. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galle, A.; Manaharlal, H.; Griffin, S.; Osman, N.; Roelens, K.; Degomme, O. A qualitative study on midwives’ identity and perspectives on the occurrence of disrespect and abuse in Maputo city. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodnett, E.D.; Gates, S.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Sakala, C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 7, CD003766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Goel, R.; Gogoi, A.; Caleb-Varkey, L.; Manoranjini, M.; Ravi, T.; Rawat, D. Presence of birth companion—A deterrent to disrespectful behaviours towards women during delivery: An exploratory mixed-method study in 18 public hospitals of India. Health Policy Plan. 2021, 36, 1552–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.A.; George, A.S.; Chebet, J.J.; Mosha, I.H.; Mpembeni, R.N.M.; Winch, P.J. Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janevic, T.; Sripad, P.; Bradley, E.; Dimitrievska, V. “There’s no kind of respect here”. A qualitative study of racism and access to maternal health care among Romani women in the Balkans. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, J.; Miller, S.; Bukusi, E.; Sande, J.; Cohen, C. HIV/AIDS and maternity care in Kenya: How fears of stigma and discrimination affect uptake and provision of labor and delivery services. AIDS Care 2008, 20, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haut Conseil à L’égalité entre les Femmes et les Hommes. Les Actes Sexistes Durant le Suivi Gynécologique et Obstétrical. Des Remarques Aux Violences, la Nécessité de Reconnaître, Prévenir et Condamner le Sexisme [Sexist Acts during Gynecological and Obstetrical Follow-Up, From Remarks to Violence, the Need to Recognize, Prevent and Condemn Sexism]. 2018. Available online: https://bit.ly/2MvJtAy (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Rivard, A. Histoire de l’Accouchement Dans un Québec Moderne [History of Childbirth in a Modern Quebec]; Anuncio Publicado; Les Éditions du Remue-Ménage: Montréal, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear-Smith, F.; Buetow, S. Power issues in the doctor-patient relationship. Health Care Anal. 2001, 9, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, S.; Ferron-Parayre, A. To Use or Not to Use the Term “Obstetric Violence”: Commentary on the Article by Swartz and Lappeman. Violence Against Women 2021, 27, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization’s Global Health Workforce Statistics: Nurses and Midwives (per 1000 People). WHO. 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.NUMW.P3?locations=GH (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Turner, L.; Culliford, D.; Ball, J.; Kitson-Reynolds, E.; Griffiths, P. The association between midwifery staffing levels and the experiences of mothers on postnatal wards: Cross sectional analysis of routine data. Women Birth 2022, 35, e583–e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE Guidelines: Intrapartum Care for Healthy Women and Babies. 2014. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190/chapter/recommendations#care-in-established-labour (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Caughey, A.B.; Cahill, A.G.; Guise, J.M.; Rouse, D.J. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Safe childbirth Checklist; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/research/safe-childbirth (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Mishra, A.; Jacob, S. ‘Safe’, yet violent? Women’s experiences with obstetric violence during hospital births in rural Northeast India. Cult. Health Sex. 2017, 20, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yalley, A.A. “We Beat Them to Help Them Push”: Midwives’ Perceptions on Obstetric Violence in the Ashante and Western Regions of Ghana. Women 2023, 3, 22-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3010002

Yalley AA. “We Beat Them to Help Them Push”: Midwives’ Perceptions on Obstetric Violence in the Ashante and Western Regions of Ghana. Women. 2023; 3(1):22-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleYalley, Abena Asefuaba. 2023. "“We Beat Them to Help Them Push”: Midwives’ Perceptions on Obstetric Violence in the Ashante and Western Regions of Ghana" Women 3, no. 1: 22-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3010002

APA StyleYalley, A. A. (2023). “We Beat Them to Help Them Push”: Midwives’ Perceptions on Obstetric Violence in the Ashante and Western Regions of Ghana. Women, 3(1), 22-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3010002