The Quality of Life Definition: Where Are We Going?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Search of Evidences

3. Results

3.1. Evolution the Quality of Life Concept

- Physical health (somatic sensations, disease symptoms)

- Mental health (positive sense of well-being, nonpathological forms of psychological distress or diagnosable psychiatric disorders)

- Social health (aspects of social contacts and interactions)

- Functional health (self-care, mobility, physical activity level and social role functioning in relation to family and work).

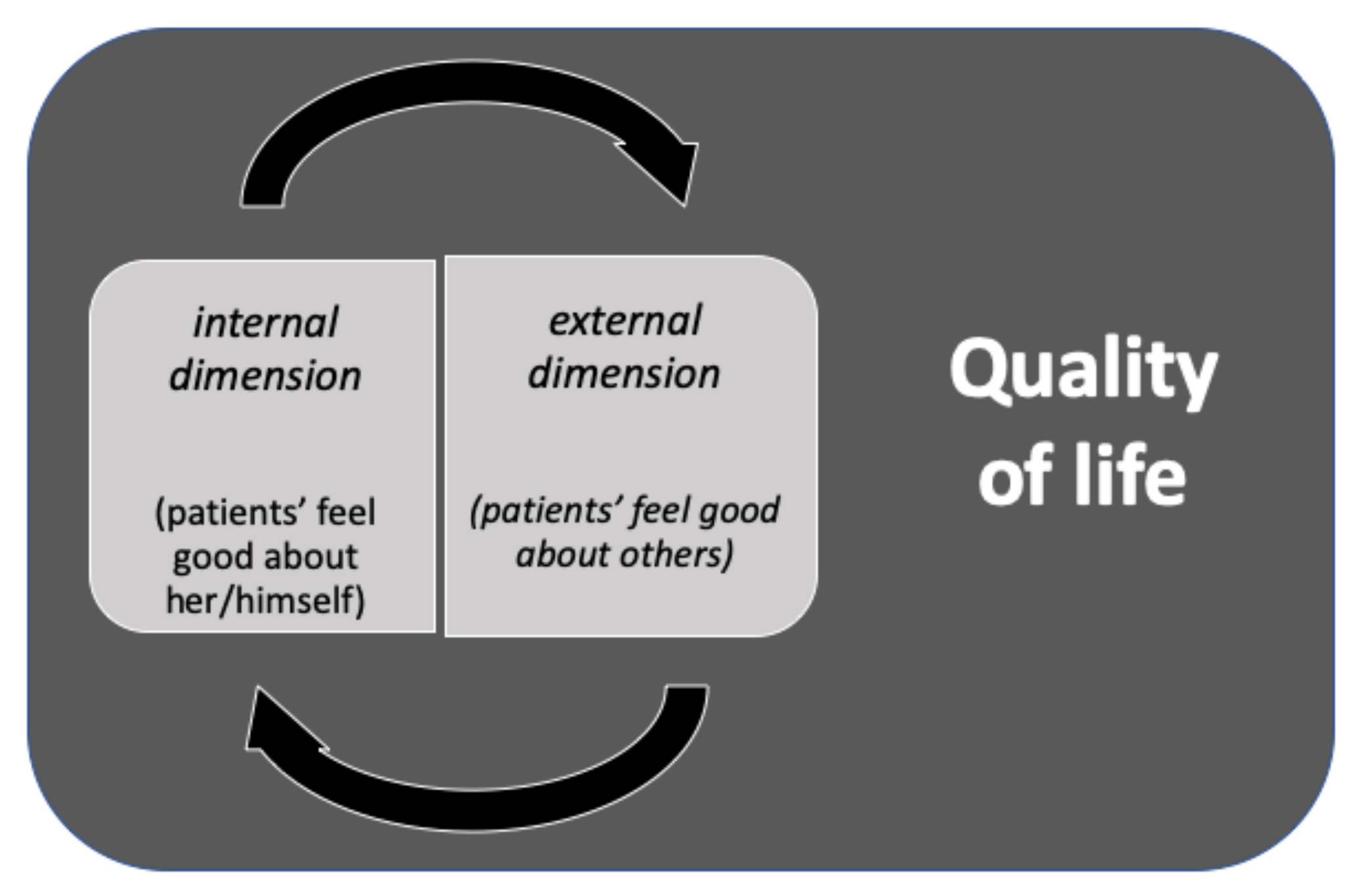

- The objective dimension (outsider)

- The subjective dimensions (insider)

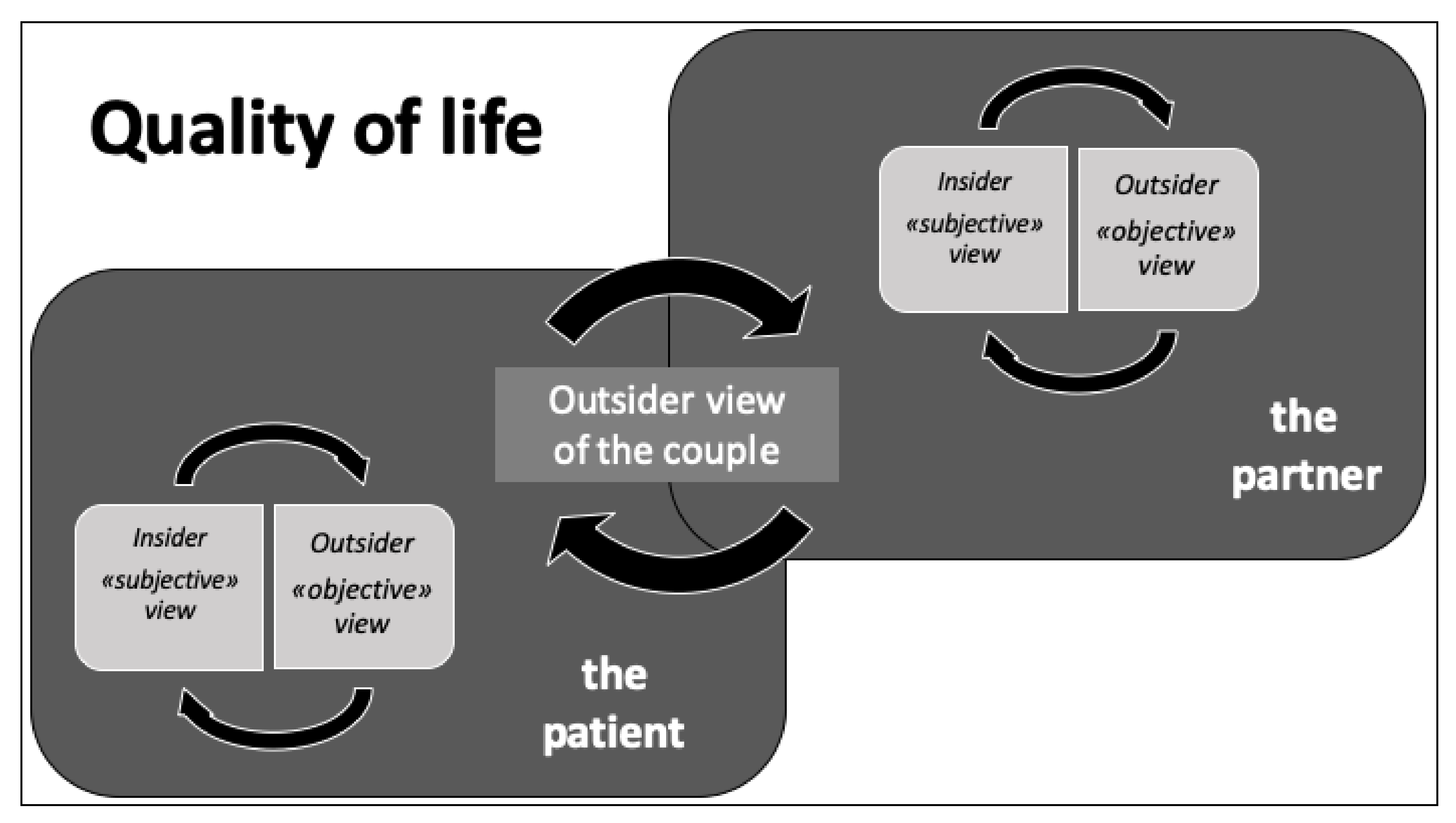

3.2. The Quality of Life Concept and the Doctor–Patient Relationship

- -

- Exploring both disease and the patients’ illness experience

- -

- Understanding the whole person

- -

- Finding common ground

- -

- Incorporating prevention and health promotion

- -

- Enhancing the patient-doctor relationship

- -

- Being realistic [18].

3.3. Cross-Cultural and Religious Dimensions of QoL

3.4. Quality of Life Assessment Tools

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.W.M. Definitions of quality of life: What has happened and how to move on. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2014, 20, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkinton, J.R. Medicine and quality of life. Ann. Intern. Med. 1966, 64, 711–714. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Köves, B.; Cai, T.; Veeratterapillay, R.; Pickard, R.; Seisen, T.; Lam, T.B.; Yuan, C.Y.; Bruyere, F.; Wagenlehner, F.; Bartoletti, R.; et al. Benefits and Harms of Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by the European Association of Urology Urological Infection Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol. 2017, 72, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The constitution of the World Health Organization. WHO Chron. 1947, 1, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Bush, J.W. Health-related quality of life measurement for evaluation research and policy analysis. Health Psychol. 1982, 1, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Reeve, B.B. Measurement and Modeling of Health-Related Quality of Life. In Epidemiology and Demography in Public Health; Killewo, J., Heggenhougen, H.K., Quah, S.R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, G.W. Utility approach to measuring health-related quality of life. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Brazier, J. Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference? Pharmacoeconomics 2016, 34, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, N.K.; Mattson, M.E.; Furberg, C.D.; Elinson, J. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. Am. J. Cardiol. 1984, 54, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldwein, F.L.; Sánchez-Salas, R.E.; Sánchez-Salas, R.; Teloken, P.E.; Teloken, C.; Castillo, O.; Vallancien, G. Health and quality of life in urology: Issues in general urology and urological oncology. Arch Esp Urol. 2009, 62, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, N.K. Quantitative issues in health-related quality of life assessment. Health Policy 1988, 10, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkers, M.P.J.M. Quality of life of individuals with spinal cord injury: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and research findings. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2005, 42, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995, 273, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevach, J.; Weiner, A.; Morgans, A.K. Quality of Life-Focused Decision-Making for Prostate Cancer. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2019, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Morgia, G.; Carrieri, G.; Terrone, C.; Imbimbo, C.; Verze, P.; Mirone, V.; IDIProst® Gold Study Group. An improvement in sexual function is related to better quality of life, regardless of urinary function improvement: Results from the IDIProst® Gold Study. Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 2013, 85, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmick, A.; Juergensen, M.; Rohde, V.; Katalinic, A.; Waldmann, A. Assessing health-related quality of life in urology—A survey of 4500 German urologists. BMC Urol. 2017, 17, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, M. Reflections on the doctor–patient relationship: From evidence and experience. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2005, 55, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Nunzio, C.; Presicce, F.; Lombardo, R.; Trucchi, A.; Bellangino, M.; Tubaro, A.; Moja, E. Patient centered care for the medical treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with benign prostatic obstruction: A key point to improve patients’ care—A systematic review. BMC Urol. 2018, 18, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittmann, D.; Carolan, M.; Given, B.; Skolarus, T.A.; An, L.; Palapattu, G.; Montie, J.E. Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 2509–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guercio, C.; Mehta, A. Predictors of Patient and Partner Satisfaction Following Radical Prostatectomy. Sex. Med. Rev. 2018, 6, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I.; Kim, H.J.; Shiu, C.; Goldsen, J.; Emlet, C.A. Successful Aging Among LGBT Older Adults: Physical and Mental Health-Related Quality of Life by Age Group. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guarnaccia, P.J. Anthropological perspectives. The importance of culture in the assessment of quality of life. In Quality of Life and Pharmaeconomics in Clinical Trials, 2nd ed.; Spilker, B., Ed.; Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996; pp. 523–529. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, S.; Carlson, D.; Billington, R.; Orley, J. The WHO quality of life assessment instrument (WHOQOL-Bref): The importance of its items for cross-cultural research. Qual. Life Res. 2001, 10, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Cañamero, B.; Bishara, T.; Otegi-Olaso, J.R.; Minguez, R.; Fernández, J.M. Measurement of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Corporate Sustainability Indexes, Rankings and Ratings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, L.R.; Williams, S.L.; Haskard, K.B.; DiMatteo, M.R. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2005, 1, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Ries, A.L. Quality of Life: Concept and Definition. COPD J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2007, 4, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.L.K. Subjective Quality of Life Measures—General Principles and Concepts. In Handbook of Disease Burdens and Quality of Life Measures; Preedy, V.R., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, C.; Briffa, N. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS) in patients undergoing heart valve surgery: Why should we measure them and which instruments should we use? Open Heart 2016, 3, e000315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Protopapa, E.; van der Meulen, J.; Moore, C.M.; Smith, S.C. Patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires for men who have radical surgery for prostate cancer: A conceptual review of existing instruments. BJU Int. 2017, 120, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, S.; Leiblum, C.; Ferguson, S.D.; D’Agostino, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Martial Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Items | Type | Area | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck Depression Inventory | 21 | Psychometric test | Depression | Influenced by physical symptom |

| Sickness Impact Profile | 136 | Psychometric test | General Health status | Accurate in chronic conditions |

| Short Form Health Survey | 36 | Psychometric test | General Health status | Accurate in chronic conditions |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, T.; Verze, P.; Bjerklund Johansen, T.E. The Quality of Life Definition: Where Are We Going? Uro 2021, 1, 14-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro1010003

Cai T, Verze P, Bjerklund Johansen TE. The Quality of Life Definition: Where Are We Going? Uro. 2021; 1(1):14-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro1010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Tommaso, Paolo Verze, and Truls E. Bjerklund Johansen. 2021. "The Quality of Life Definition: Where Are We Going?" Uro 1, no. 1: 14-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro1010003

APA StyleCai, T., Verze, P., & Bjerklund Johansen, T. E. (2021). The Quality of Life Definition: Where Are We Going? Uro, 1(1), 14-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro1010003