Abstract

Urolithiasis is a common condition, and it represents a large number of hospital visits. Under the term infundibulopelvic dysgenesis, many conditions amongst a spectrum of congenital disorders of the pelvicalyceal system are described. Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) is an effective and safe treatment modality in the management of urinary system stone disease. Fluoroscopic imaging is a cornerstone in endourology. Herein, we present a case where we diagnosed an obstructed calyx during RIRS for renal calculi and operated on it. In this extraordinary case, contrast agent was trapped in the calyx mimicking a renal stone and that was the reason that we discovered the infundibular stenosis. The patient, 24 h after the operation, left the hospital without any complications reported.

1. Introduction

Nephrolithiasis is the formation of stones within the kidneys. Urolithiasis is diagnosed often, and it accounts for a large number of hospitalized patients. It depends on geographical, climatic, ethnic, dietary, and genetic factors. The prevalence rates for urinary stones vary from 1% to 20% [1]. Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) is thought to be an effective and safe treatment modality in the management of urinary system stone disease. In various studies, it has been proved that RIRS is an effective and reliable method in the treatment of renal stones. The success rates of RIRS vary between 65% and 92% [2]. Fluoroscopic imaging plays an important role in endourology. Fluoroscopy is generally used for insertion of guidewires, ureteral access sheaths and double-J stents, identification of stone localization, and detection of renal anatomy. Under the term infundibulopelvic dysgenesis, several conditions amongst a spectrum of congenital disorders of the pelvicalyceal system are described. In an obstructed calyx, lithiasis can be present due to the stenosis of the infundibulum that affects the normal urine flow. Herein, we present a case where we diagnosed an obstructed calyx during RIRS for renal calculi and operated on it.

2. Case Presentation

A female patient, age 62, was admitted to us after a renal colic for further investigation and treatment. Her medical history revealed hypertension under medication and diabetes mellitus that she was not aware of. The blood tests showed WBC 7800/μL, HTC 37%, PLT 187 × 103/μL, creatinine 1.1 mg/dL, INR 0.97 and CRP 3 mg/dL. Urine culture was negative and the urine test revealed microscopic hematuria. She underwent CT scan that showed stones with a diameter of 3 cm. Because of the high calculi load, we proposed retrograde renal surgery (RIRS) according to the European Urology Association guidelines in order to remove the stones. The patient agreed and we proceeded to the operation room.

3. Results

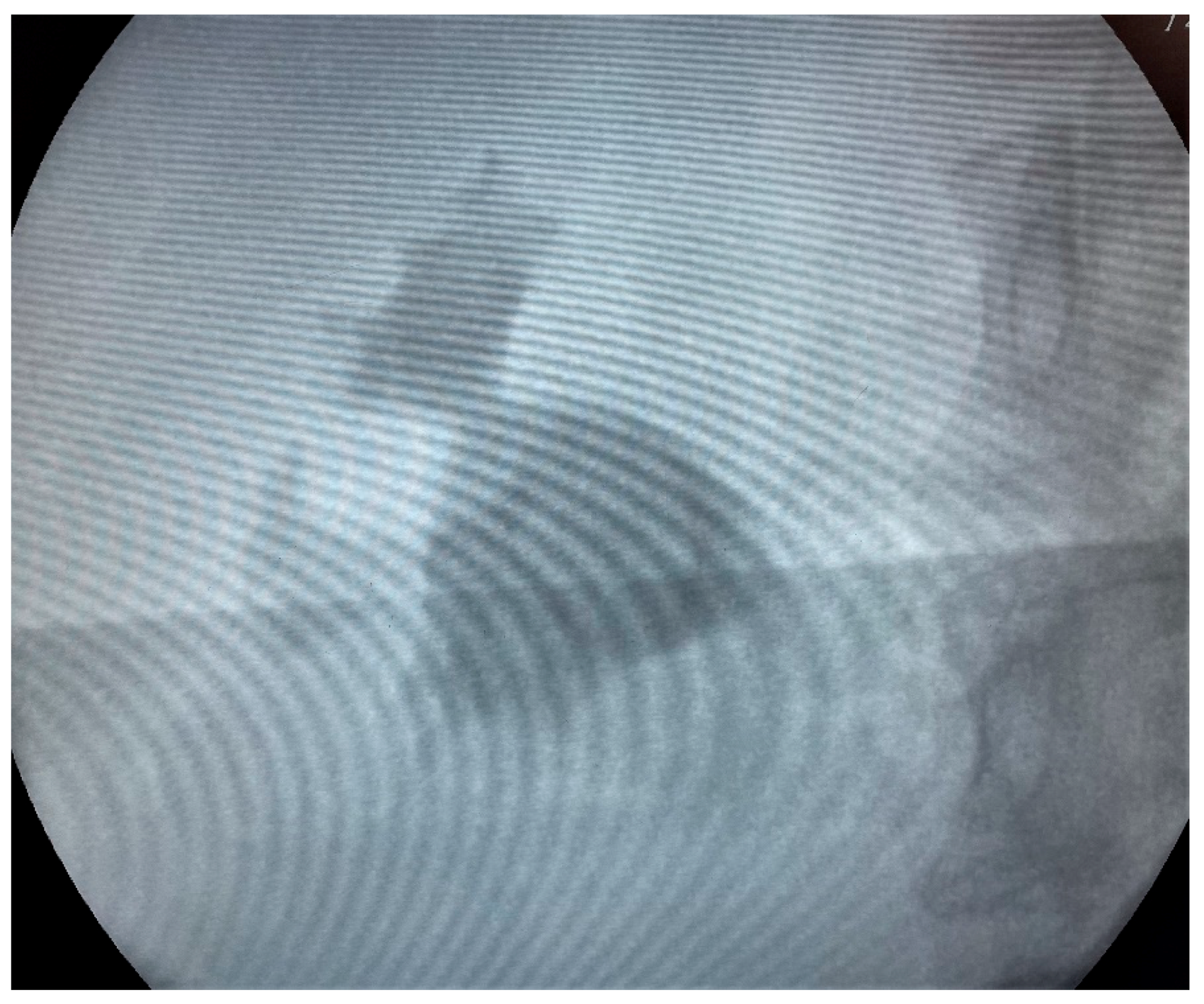

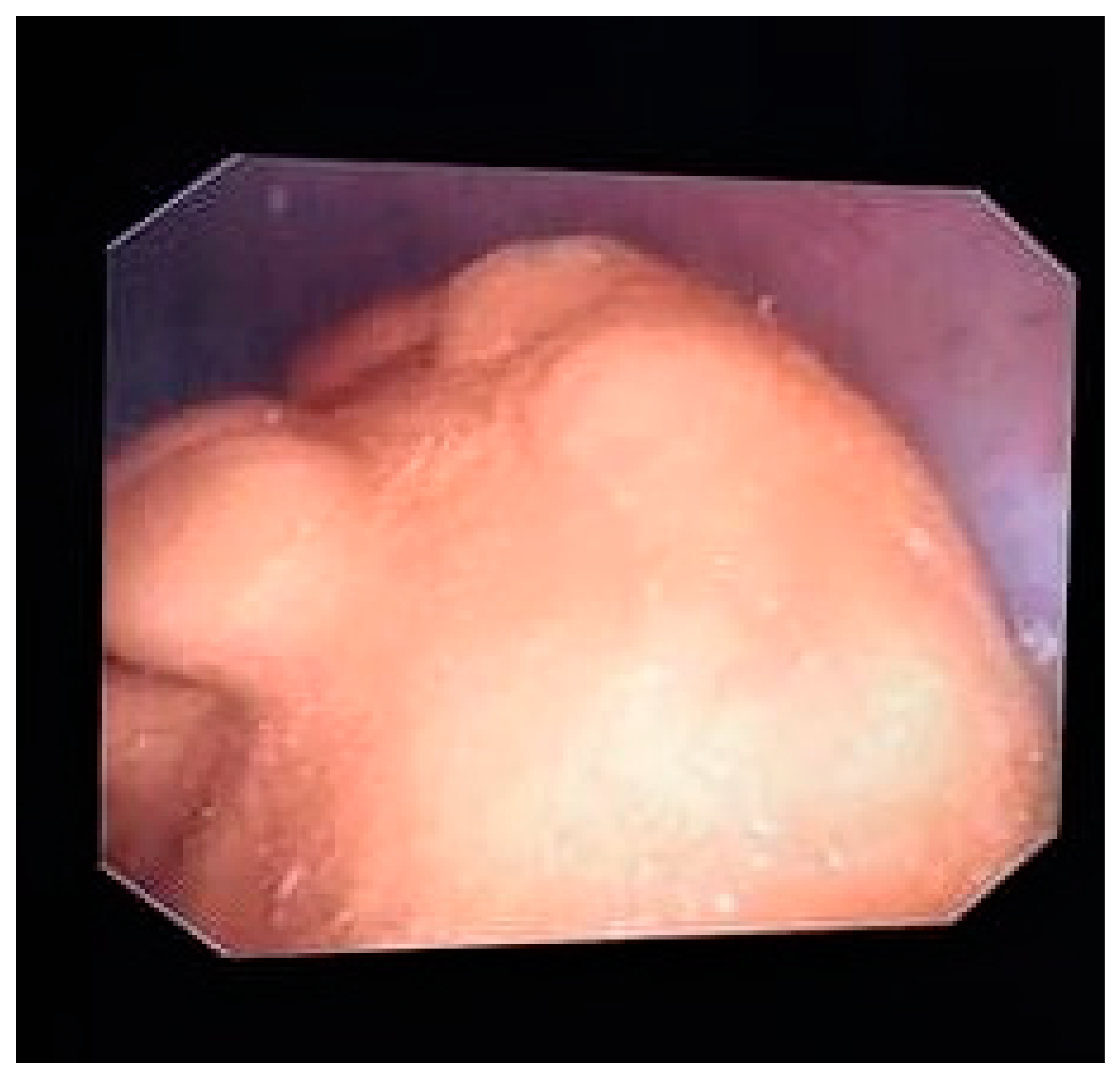

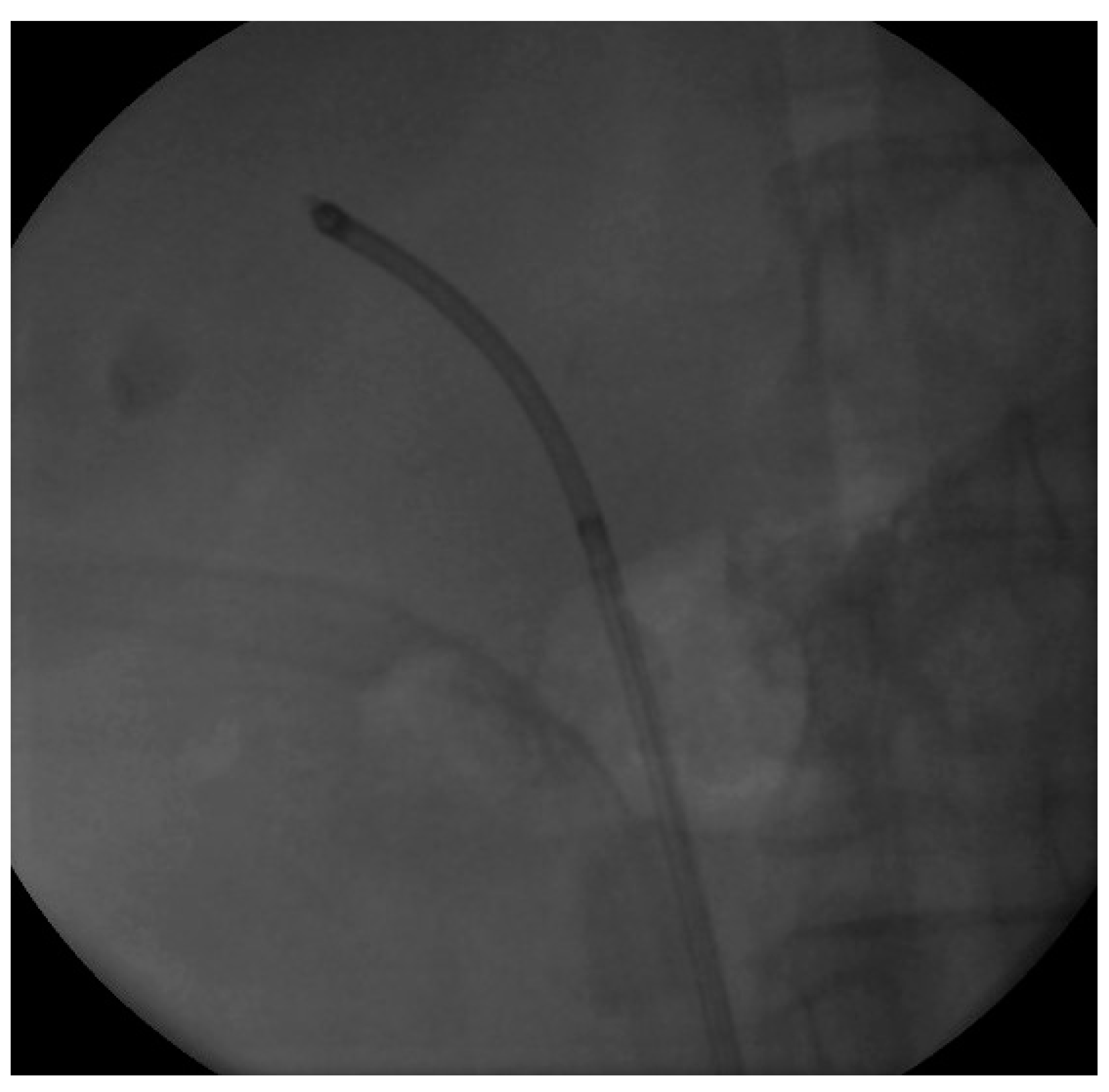

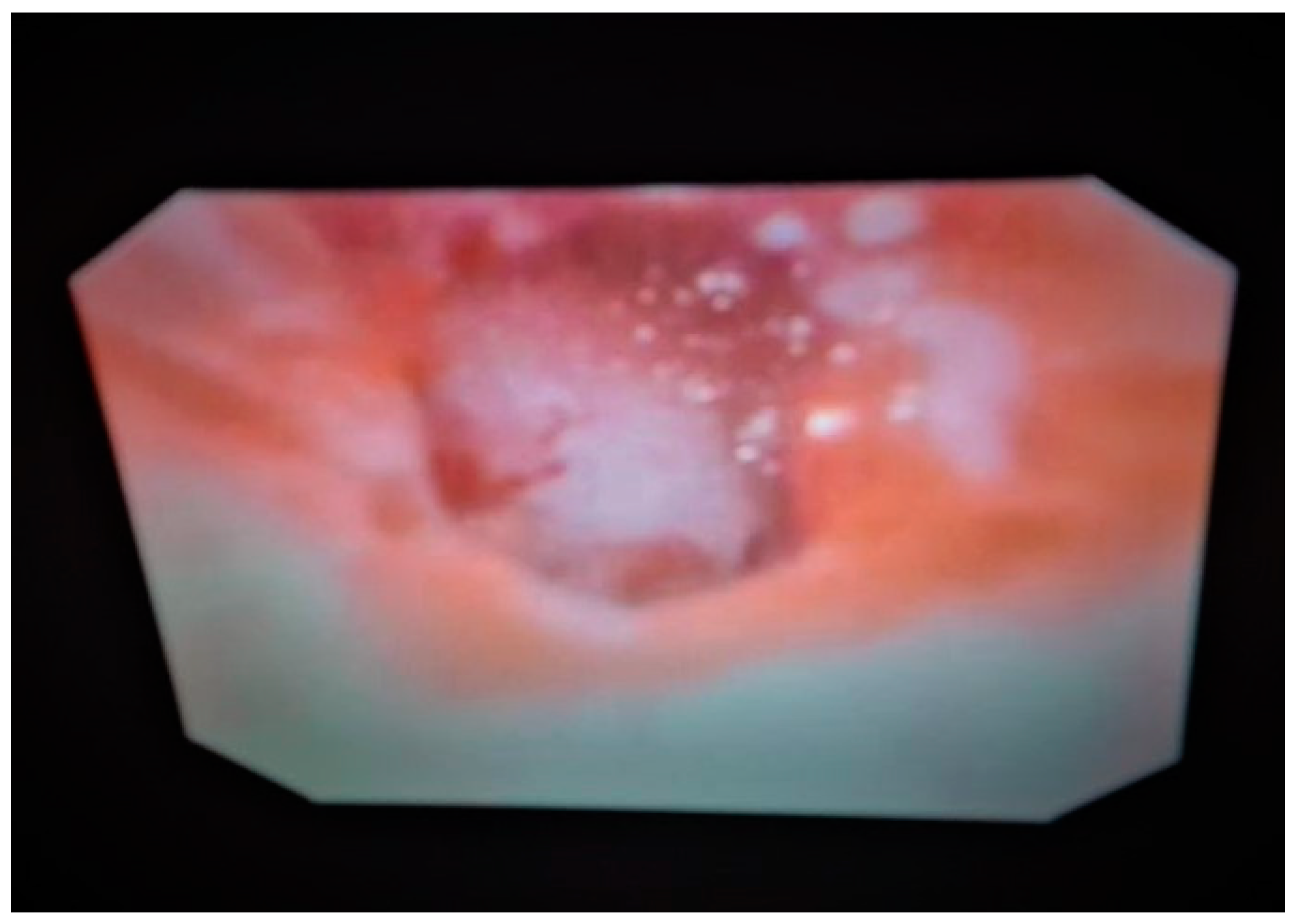

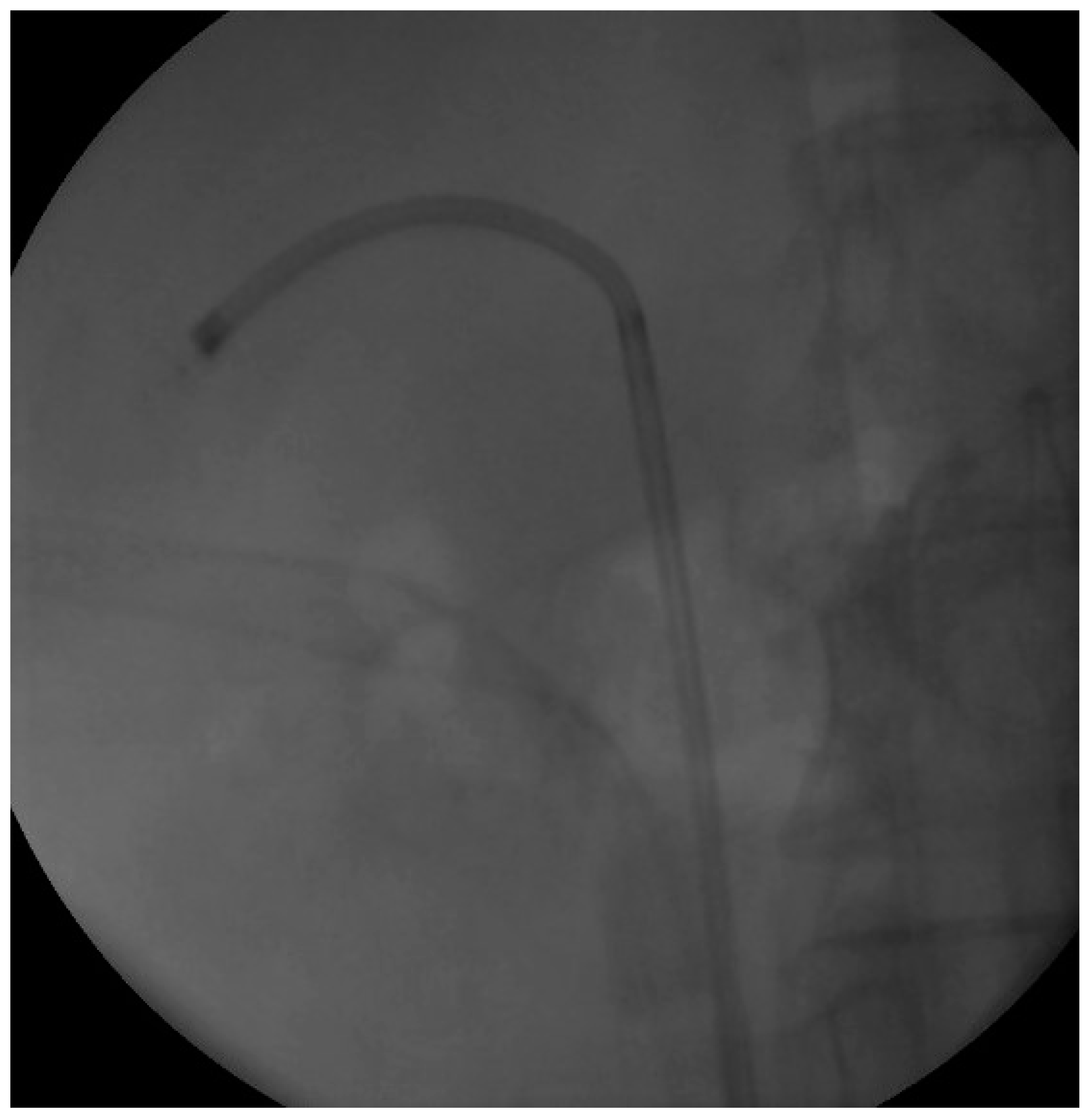

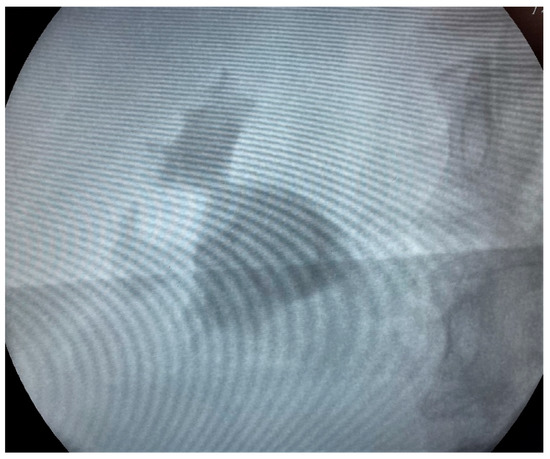

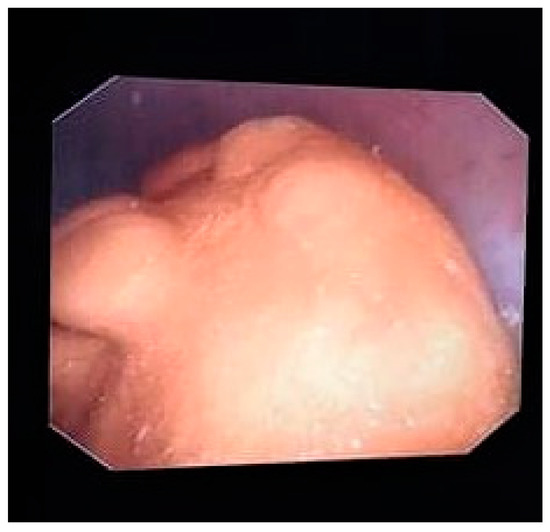

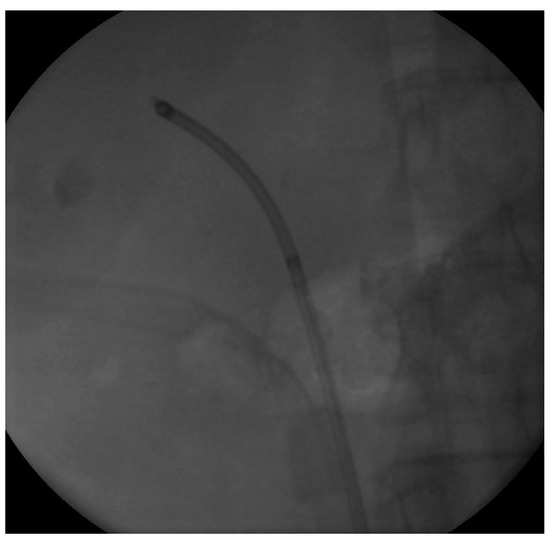

We proceeded with our standardized protocol of RIRS. Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the lithotomy position. At first, we performed a cystoscopy of the bladder. We found the right ureteral orifice and placed an ureteral catheter. Via the catheter, contrast agent was infused and, under fluoroscopy, the renal collecting system and the calculi was detected (Figure 1). The insertion of the guidewire followed, an ureteral access sheath was placed and through it we reached the kidney with a flexible ureteroscope of 8.6 French. The stones were found in the upper calyx and in the pelvis (Figure 2) so we began lithotripsy using holmium laser, checking throughout the whole procedure with fluoroscopy. In the meantime, the contrast agent was almost eliminated from the pelvicalyceal system and the stones were efficiently exported. Although we could not see any other calculi in the system, in the fluoroscopy there seemed to be one more (Figure 3). Therefore, we continued our endoscopy in order to find it. We came up to a small aperture in the spot that was indicated to us by the fluoroscopy, so we diagnosed an infundibulum stenosis and thought that the calculi would be within the calyx. The ureteroscope could not be inserted due to the stenosis, so we used the laser to widen the aperture. When the bore was opened and the access to the calyx was provided (Figure 4) we still could not found any calculi. In the fluoroscopy the sign has disappeared (Figure 5) so we understood that the contrast agent was entrapped in the calyx mimicking a stone in the fluoroscopy. The patient was stone free. We placed a double-J stent according to our protocol and the operation has ended. The patient the next day was free to leave the hospital without any complications, according to Clavien–Dildo system.

Figure 1.

Fluoroscopy image of the pelvicalyceal system showing the stone.

Figure 2.

Endoscopy image of the stone.

Figure 3.

Fluoroscopy Image at the end of the lithotripsy.

Figure 4.

The calyx after the widening of the infundibulum.

Figure 5.

Image at the end of the operation showing no more contrast agent.

4. Discussion

Nephrolithiasis is the term used to describe the formation of renal stones. When these stones exit the renal pelvis and move into the urinary collecting system, including the ureters, bladder, and urethra, this is called urolithiasis. Urolithiasis affects about one out of 11 people in the U.S. and the prevalence rates for urinary stones range from 1% to 20% [1]. Urolithiasis occurs primarily through supersaturation of urine. There are a number of different risk factors such as diet, prior personal and family history of stones, environmental factors, medications, poor oral fluid intake, high animal-derived protein intake, high oxalate intake and high salt intake [3].

Urolithiasis commonly presents with flank pain, hematuria, and nausea/vomiting. Our case presented with these signs too. Standard evaluation includes a detailed medical history and physical examination. According to European Association of Urology lithiasis guidelines, a patient should be examined for white and red cells in the urine dipstick, nitrates, urine microscopy and culture are also needed. Serum blood culture should include creatinine, blood cell count, uric acid, calcium, sodium, potassium, CRP. Non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (NCCT) has become the standard for evaluating acute flank pain. NCCT is significantly more accurate than intravenal urography or ultrasound in diagnosing urolithiasis [4]. NCCT was the radiographic examination of choice in our patient, too.

The treatment of urolithiasis includes both conservative medical therapies and surgical interventions and depends on the patient’s acute presentation. Pain control is an important intervention and it can be obtained by oral and IV anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) as first-line treatments. There are various procedures of acute or delayed urologic interventions, including extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL), flexible ureteroscopy (URS), and percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) is proved to be both effective and safe treatment modality in the management of urinary system stone disease.

Fluoroscopic imaging plays a great role in endourology. Fluoroscopy is generally used for insertion of guidewires, ureteral access sheaths and double-J stents, identification of stone localization, determination of renal anatomy, and ureteral balloon dilatation during ureteroscopy (URS). A recent systematic review including renal stones >2 cm showed a cumulative stone free rate (SFR) of 91% with 1.45 procedures/patient [5,6,7].

Infundibulopelvic dysgenesis is a rare condition characterized by congenital malformation of the pelvicalyceal system. The spectrum of gongenital disorders includes focal and multifocal abnormalities leading to multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK), infundibulopelvic stenosis, calyceal diverticula, and ureteropelvic junction obstruction [8,9]. The theory assumes that infundibulopelvic dysgenesis is the result of early or late budding of the ureter during embryogenesis [10]. During normal development of the metanephros, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), a peptide secreted by the metanephric mesenchyme, stimulates and localizes outgrowth of the ureteric bud via activation of the RET receptor. Many other factors, including PAX2, Eya1, and FoxC1/C2, positively and negatively regulate the expression of GDNF, thereby guiding development of the ureteric bud. Many of the factors regulating ureteric bud outgrowth also stimulate branching and dilatation to form the renal collecting system. PAX2 and vitamin A are transcription factors that induce branching of the ureteric bud. Meanwhile, both the Emx2 and Sall1 genes seem to be necessary for stimulating branching and dilation of ureteric buds. The absence of any of these stimulatory factors, or excess of inhibitory factors, could lead to a scenario where the ureteric bud does not branch and dilate appropriately, causing stenosis of the calyceal system. The earlier the stage at which these imbalances occur, the more significant the resulting dysgenesis is likely to be [11].

As with any other obstructed kidney collecting system, a calyx with an infundibulum stenosis is in high risk for stone formation as the free urine flow is disturbed. Infundibular dysgenesis can be diagnosed by CT urography during the investigation of flank pain proposing lithiasis or upper tract infection. In many cases, it is diagnosed accidentally when operating for stone removal.

In our case, there were no signs of a dilating calyx in the CT and the pain occurred concomitantly with the stone formation, with no previous symptoms suggesting evaluation of the upper tract. During fluoroscopy, the sign that drew our attention was a radiopaque lesion that seemed similar to a stone fragment, while the contrast agent has left the pelvicalyceal system—or so we thought at that time. Throughout the inspection, no stone was found and, using fluoroscopy, we came up with the small aperture that turned out to be an infundibular stenosis as described before. Any CT or fluoroscopic image showing lithiasis that cannot be found during endoscopy should suspect the urologist to an entrapped calyx.

The incidence of calyx diverticulum is 0.6% among the general population [12]. The incidence of stone formation in a calyx diverticulum is 10–50% [2]. Koopman et al. dilated the calyx neck with either balloon dilatator or laser incision, and succeeded in reaching the stone in calyx in 94% of patients. General stone free rate was 90%. These numbers suggest RIRS as an efficient treatment modality in infundibular stenosis patients. A case such as this, with the contrast agent being trapped in a calyx mimicking lithiasis, is anecdotal in the literature.

5. Conclusions

Infundibular stenosis is a rare situation. Lithiasis in the entrapped calyx has been efficiently described. The case of contrast agent being trapped in the calyx so that could mimic a kidney stone is never recorded in the literature. Widening of the infundibulum using laser is an approved and safe procedure in endoscopy surgery. The fluoroscopy images are worth reporting and that was the purpose of this paper. Any renal stone that cannot be found during RIRS could be suggesting an infundibular dysgenesis. The operating urologist should be suspicious for such a condition and inspect carefully the pelvicalyceal system for signs of an entrapped calyx.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z. and F.V.; methodology, G.Z. and F.V.; software, G.Z. and F.V.; validation, G.Z. and F.V.; formal analysis, G.Z. and F.V.; investigation, G.Z. and F.V.; resources, G.Z. and F.V.; data curation, G.Z. and F.V.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z. and F.V.; writing—review and editing, G.Z. and F.V.; visualization, G.Z. and F.V.; supervision, G.Z. and F.V.; project administration, G.Z. and F.V.; funding acquisition, G.Z. and F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Trinchieri, A. Epidemiology, in Stone Disease; Segura, C.P., Pak, C.Y., Preminger, G.M., Tolley, D., Eds.; Health Publications: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç, Ö.; Akand, M.; Van Cleynenbreugel, B. Retrograde intrarenal surgery for renal stones—Part 2. Turk. J. Urol. 2017, 43, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chung, M.J. Urolithiasis and nephrolithiasis. JAAPA 2017, 30, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worster, A.; Preyra, I.; Weaver, B.; Haines, T. The accuracy of noncontrast helical computed tomography versus intravenous pyelography in the diagnosis of suspected acute urolithiasis: A meta-analysis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2002, 40, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendt-Nordahl, G.; Mut, T.; Krombach, P.; Michel, M.S.; Knoll, T. Do new generation flexible ureterorenoscopes offer a higher treatment success than their predecessors? Urol. Res. 2011, 39, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binbay, M.; Yuruk, E.; Akman, T.; Ozgor, F.; Seyrek, M.; Ozkuvanci, U.; Berberoglu, Y.; Muslumanoglu, A.Y. Is there a difference in outcomes between digital and fiberoptic flexible ureterorenoscopy procedures? J. Endourol. 2010, 24, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraghty, R.; Abourmarzouk, O.; Rai, B.; Biyani, C.S.; Rukin, N.J.; Somani, B. Evidence for Ureterorenoscopy and Laser Fragmentation (URSL) for Large Renal Stones in the Modern Era. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2015, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlenhuth, E.; Amin, M.; Harty, J.I.; Howerton, L.W. Infundibulopelvic dysgenesis: A spectrum of obstructive renal disease. Urology 1990, 35, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dally, E.A.; Raman, A.; Webb, N.R.; Farnsworth, R.H. Unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney with progressive infundibular stenosis in the contralateral kidney: Experience at 1 center and review of literature. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurzia, M.J.; Costantinescu, A.R.; Barone, J.G. Childhood infundibular stenosis. Urology 2002, 60, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wein, A.J.; Kavoussi, L.R.; Novick, A.C.; Partin, A.W.; Peters, C.A. Campbell-Walsh urology. In Normal Development of the Genitourinary Tract; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 2975–3001. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, S.G.; Fuchs, G. Management of stones associated with intrarenal stenosis: Infundibular stenosis and caliceal diverticulum. J. Endourol. 2013, 27, 1546–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).