A Systematic Review of Contaminants of Concern in Uganda: Occurrence, Sources, Potential Risks, and Removal Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Analysis and Synthesis

2.7. Limitations

3. Results and Discussion

4. Challenges of CoCs in Uganda

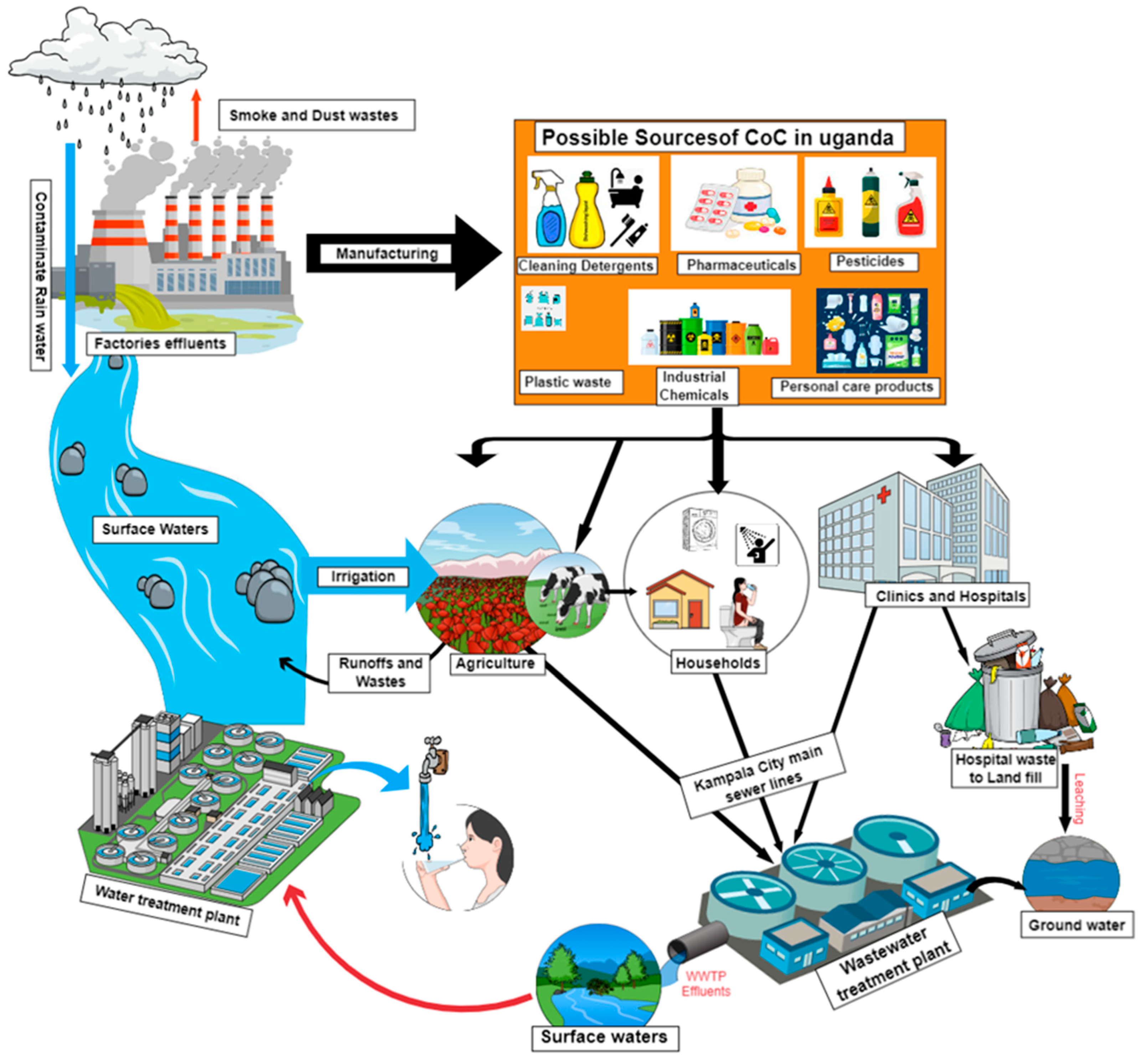

4.1. Sources, Occurrence, Fate, and Transport of CoCs in Uganda

4.1.1. CoCs in Ugandan Surface Waters

4.1.2. Urban Runoffs and Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTP) Effluents as Sources of CoCs

4.1.3. CoCs in Sediments

4.1.4. Ambient Air as a Transport Medium for CoCs in Uganda

4.1.5. CoCs Detected in Various Food Items Grown in Uganda

5. Current Monitoring and Regulation Efforts in Uganda

6. Mitigation Strategies and Future Directions for Addressing Risks Posed by CoCs

| Treatment Method | Advantages | Challenges | Contaminants Removed | Treatment Efficiency (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Methods | |||||

| Coagulation | Effective for suspended particles and some heavy metals with relatively low operational costs | Chemical costs Sludge disposal can be problematic | Pesticides, heavy metals | 80–95% | [157,158] |

| Flocculation | Effective for particulate matter | Chemical usage and residual disposal | Heavy metals, | [157,158] | |

| Sedimentation | Cost-effective and reduces suspended solids | Inefficient for dissolved contaminants Large space requirements | Suspended solids, radionuclides | 60–90% | [159] |

| Filtration (Sand/Granular Media) | Effective for removing a wide range of contaminants | Clogging and frequent backwashing | Turbidity, bacteria, protozoa, microplastics | 95–99% | [157,160] |

| Unconventional | |||||

| Membrane Filtration, | Robust against variations in water | fouling and scaling issues in membranes | Microplastics, pharmaceuticals | 4–56% | [157,161] |

| Activated Carbon Adsorption) | Removes most contaminants | Energy intensive for preparation of activated carbon | Personal care products, hydrocarbons, persistent organic pollutants, biotoxins, and mycotoxins | 99.7% | [162,163] |

| Membrane bioreactors (MBR) | Sustainable and breaks down organic matter | Slower treatment compared to other methods | Organic compounds, pharmaceuticals | 70–90% | [164,165] |

| Constructed wetlands | Cost-effective natural system, effective for wastewater | Seasonal performance variability, limited removal of some contaminants | Pathogens, heavy metals, organic compounds, pharmaceutical residues | 74–99% | [164,165] |

| Chemical processes | |||||

| Advanced Oxidation Processes [AOP] | Effective for breaking down organic compounds | High operational costs | Organic compounds, pesticides, pharmaceuticals | 95–99% | [166,167] |

| Chemical extraction/Solvent extraction | Effective for the removal of heavy metals, applicable to a wide range of contaminant removal | High operational costs, potential risks associated with solvents | Model pollutants, bromocresol green, and phenols, oil-based drilling cuttings | 99% | [168,169] |

| Fenton and Photo-Fenton oxidation | Degradation and mineralization of persistent organic compounds | Difficult to treat large volumes of wastewater | Organic pollutants in cosmetic water | 95% | [170,171] |

| Photocatalysis (TiO2) | High reaction rates upon using a catalyst | Cost associated with artificial UV lamps and electricity | Pharmaceuticals, volatile organic compounds, synthetic dyes, and biocides | 90% | [172,173] |

| Physical processes | |||||

| Ultraviolet (UV) Disinfection | No chemical addition Effective for disinfection and low energy consumption | Ineffectiveness against organic contaminants | Persistent organic pollutants, pharmaceuticals | 91.1% | [174] |

| Filtration (Membrane) | Effective for removing microorganisms and nanoparticles | Membrane fouling High operational costs | Microorganisms, nanoparticles | 90–99% | [175,176] |

| Micro or Ultrafiltration | Effective removal of pathogens | Not fully effective in removing some EPs as pore sizes vary from 100 to 1000 times, larger than the micropollutants, membrane fouling | Micro- and nano-plastics for particles larger than 100 μm | 86.5–99.9% | [177] |

| Reverse Osmosis | Removes a wide range of contaminants, including salts | High energy requirements, membrane fouling | Dissolved salts, particles, colloids, organic compounds, bacteria, and pyrogens | 90–99% | [178,179] |

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMichael, A.J. The urban environment and health in a world of increasing globalization: Issues for developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Santhakumari, M.; Sagar, N. The Environmental Threats Our World Is Facing Today. In Handbook of Environmental Materials Management; Hussain, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bunke, D.; Moritz, S.; Brack, W.; Herráez, D.L.; Posthuma, L.; Nuss, M. Developments in society and implications for emerging pollutants in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M.; Demnerová, K.; Aamand, J.; Agathos, S.; Fava, F. Emerging pollutants in the environment: Present and future challenges in biomonitoring, ecological risks, and bioremediation. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geissen, V.; Mol, H.; Klumpp, E.; Umlauf, G.; Nadal, M.; van der Ploeg, M.; van de Zee, S.E.A.T.M.; Ritsema, C.J. Emerging pollutants in the environment: A challenge for water resource management. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2015, 3, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Flores, F.G.; Isac-García, J.; Dobado, J.A. Emerging Pollutants: Origin, Structure and Properties; John Wiley & Sons: Weinheim, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Xu, S.; Du, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, C.; Tang, J. Concentration, distribution, source apportionment, and risk assessment of surrounding soil PAHs in industrial and rural areas: A comparative study. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, S.; Chang, C.-C. Emerging Pollutants—Part II: Treatment. Water Environ. Res. 2018, 90, 1792–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.Y.; Bandy, J.; Beck, S.; Keen, O.; Kolankowsky, N.; Parker, A.M.; Linden, K. Emerging Pollutants—Part II: Treatment. Water Environ. Res. 2012, 84, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Xu, J. Progress in the biological and chemical treatment technologies for emerging contaminant removal from wastewater: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 323, 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughton, C.G. Non-regulated water contaminants: Emerging research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 711–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitarch, E.; Cervera, M.I.; Portolés, T.; Ibáñez, M.; Barreda, M.; Renau-Pruñonosa, A.; Morell, I.; López, F.; Albarrán, F.; Hernández, F. Comprehensive monitoring of organic micro-pollutants in surface and groundwater in the surrounding of a solid-waste treatment plant of Castellón, Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 548–549, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.E.; Thomas, S.M.; Bodour, A.A. Prioritizing research for trace pollutants and emerging contaminants in the freshwater environment. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 3462–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Gin, K.Y.H.; Lin, A.Y.C.; Reinhard, M. Impacts of emerging organic contaminants on freshwater resources: Review of recent occurrences, sources, fate, and effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 6062–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y. Emerging persistent organic pollutants in Chinese Bohai Sea and its coastal regions. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 608231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.J.; Wei, Y.L.; Yao, Y.; Ruan, Q.Q.; Zeng, E.Y. Global trends of research on emerging contaminants in the environment and humans: A literature assimilation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilachi, I.C.; Asiminicesei, D.M.; Fertu, D.I.; Gavrilescu, M. Occurrence and fate of emerging pollutants in water environment and options for their removal. Water 2021, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, K.; Dixit, U.; Ahmad Bhat, R.; Prakash Gupta, S. Removal of Arsenic—“A Silent Killer” in the Environment by Adsorption Methods. In Arsenic Monitoring, Removal and Remediation; Stoytcheva, M., Zlatev, R., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.B.; Shaikh, S.; Jain, K.R.; Desai, C.; Madamwar, D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Sources, Toxicity, and Remediation Approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 562813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, F.; McGranahan, G.; Kuylenstierna, J.C.I. Assessing health effects of air pollution in developing countries. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2001, 130, 1799–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, F.; Wondwosen, S. Assessment of the environment pollution and its impact on economic cooperation and integration initiatives of the IGAD region. In National Environment Pollution Report—Djibouti; Research Gate 2016, Technical report, 3 February; IGAD: Djibouti City, Djibouti, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matagi, S.V. Some issues of environmental concern in Kampala, the capital city of Uganda. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2002, 77, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akurut, M.; Niwagaba, C.B.; Willems, P. Long-term variations of water quality in the Inner Murchison Bay, Lake Victoria. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirenga, B.J.; Meng, Q.; Van Gemert, F.; Aanyu-Tukamuhebwa, H.; Chavannes, N.; Katamba, A.; Obai, G.; Van Der Molen, T.; Schwander, S.; Mohsenin, V. The state of ambient air quality in two Ugandan cities: A pilot cross-sectional spatial assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulio, V.; van Bavel, B.; Brorström-Lundén, E.; Harmsen, J.; Hollender, J.; Schlabach, M.; Slobodnik, J.; Thomas, K.; Koschorreck, J. Emerging pollutants in the EU: 10 years of NORMAN in support of environmental policies and regulations. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2018, 30, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.K.; Zboril, R.; McDonald, T.J. Formation and toxicity of brominated disinfection byproducts during chlorination and chloramination of water: A review. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B Pestic. Food Contam. Agric. Wastes 2014, 49, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.J. Potential health effects of emerging environmental contaminants perfluoroalkyl compounds. Yeungnam Univ. J. Med. 2018, 35, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulabako, R.N.; Nalubega, M.; Wozei, E.; Thunvik, R. Environmental health practices, constraints and possible interventions in peri-urban settlements in developing countries—A review of Kampala, Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2010, 20, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaoui, I.; Mateo-Sagasta, J. A review on occurrence of emerging pollutants in waters of the MENA region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 68090–68110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nantaba, F.; Wasswa, J.; Kylin, H.; Palm, W.U.; Bouwman, H.; Kümmerer, K. Occurrence, distribution, and ecotoxicological risk assessment of selected pharmaceutical compounds in water from Lake Victoria, Uganda. Chemosphere 2020, 239, 124642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasswa, J.; Kiremire, B.T.; Nkedi-Kizza, P.; Mbabazi, J.; Ssebugere, P. Organochlorine pesticide residues in sediments from the Uganda side of Lake Victoria. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguma, G.; Musasizi, A.; Twinomuhwezi, H.; Gonzaga, A.; Nakiguli, C.K.; Onen, P.; Angiro, C.; Okwir, A.; Opio, B.; Otema, T.; et al. Heavy Metal Contamination of Sediments from an Exoreic African Great Lakes’ Shores (Port Bell, Lake Victoria), Uganda. Pollutants 2022, 2, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekabira, K.; Origa, H.O.; Basamba, T.A.; Mutumba, G.; Kakudidi, E. Assessment of heavy metal pollution in the urban stream sediments and its tributaries. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 7, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwok, P.; Muyonga, J.H.; Sserunjogi, M.L. Pesticide residues and heavy metals in Lake Victoria Nile Perch, Lates niloticus, Belly Flap Oil. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009, 82, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssebugere, P.; Sillanpää, M.; Kiremire, B.T.; Kasozi, G.N.; Wang, P.; Sojinu, S.O.; Otieno, P.O.; Zhu, N.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, H.; et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls and hexachlorocyclohexanes in sediments and fish species from the Napoleon Gulf of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 481, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abondio, R.B.; Komakech, A.J.; Kambugu, R.K.; Kiggundu, N.; Wanyama, J.; Zziwa, A.; Kyamanywa, S. Assessment of Municipal Organic Solid Waste, as a Potential Feedstock for Briquette Production in Kampala, Uganda. J. Sustain. Bioenergy Syst. 2020, 10, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Shahid, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Murtaza, B.; Bibi, I.; Dumat, C. A comparison of technologies for remediation of heavy metal contaminated soils. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 182, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusan, A.A.; Ige, D.V.; Olawale, R. Characteristics of Soils and Crops’ Uptake of Metals in Municipal Waste Dump Sites in Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol. 2005, 17, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labu, S.; Subramanian, S.; Cheseto, X.; Akite, P.; Kasangaki, P.; Chemurot, M.; Tanga, C.M.; Salifu, D.; Egonyu, J.P. Agrochemical contaminants in six species of edible insects from Uganda and Kenya. Curr. Res. Insect Sci. 2022, 2, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matovu, H.; Li, Z.M.; Henkelmann, B.; Bernhöft, S.; De Angelis, M.; Schramm, K.W.; Sillanpää, M.; Kato, C.D.; Ssebugere, P. Multiple persistent organic pollutants in mothers’ breastmilk: Implications for infant dietary exposure and maternal thyroid hormone homeostasis in Uganda, East Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 145262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalahmeh, S.; Björnberg, E.; Elenström, A.K.; Niwagaba, C.B.; Komakech, A.J. Pharmaceutical pollution of water resources in Nakivubo wetlands and Lake Victoria, Kampala, Uganda. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayiwa, R.; Kasedde, H.; Lubwama, M.; Kirabira, J.B.; Kayondo, T. Occurrence and toxicological assessment of selected active pharmaceutical ingredients in effluents of pharmaceutical manufacturing plants and wastewater treatment plants in Kampala, Uganda. Water Pract. Technol. 2022, 17, 852–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantaba, F.; Palm, W.U.; Wasswa, J.; Bouwman, H.; Kylin, H.; Kümmerer, K. Temporal dynamics and ecotoxicological risk assessment of personal care products, phthalate ester plasticizers, and organophosphorus flame retardants in water from Lake Victoria, Uganda. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampire, E.; Kiremire, B.T.; Nyanzi, S.A.; Kishimba, M. Organochlorine pesticide in fresh and pasteurized cow’s milk from Kampala markets. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltramare, C.; Weiss, F.T.; Staudacher, P.; Kibirango, O.; Atuhaire, A.; Stamm, C. Pesticides monitoring in surface water of a subsistence agricultural catchment in Uganda using passive samplers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 10312–10328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arinaitwe, K.; Muir, D.C.G.; Kiremire, B.T.; Fellin, P.; Li, H.; Teixeira, C. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers and alternative flame retardants in air and precipitation samples from the Northern Lake Victoria Region, East Africa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pule, S.; Barakagira, A. Heavy Metal Assessment in Domestic Water Sources of Sikuda and Western Division Located in Busia District, Uganda. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2022, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbabazi, J.; Wasswa, J.; Kwetegyeka, J.; Bakyaita, G.K. Heavy metal contamination in vegetables cultivated on a major Urban wetland inlet drainage system of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 67, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, G.N.; Kiremire, B.T.; Bugenyi, F.W.B.; Kirsch, N.H.; Nkedi-Kizza, P. Organochlorine Residues in Fish and Water Samples from Lake Victoria, Uganda. J. Environ. Qual. 2006, 35, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arinaitwe, K.; Keltsch, N.; Taabu-Munyaho, A.; Reemtsma, T.; Berger, U. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the Ugandan waters of Lake Victoria: Spatial distribution, catchment release and public exposure risk via municipal water consumption. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 146970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalahmeh, S.; Tirgani, S.; Komakech, A.J.; Niwagaba, C.B.; Ahrens, L. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in water, soil, and plants in wetlands and agricultural areas in Kampala, Uganda. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwebembeire, J.; Andama, M.; Yatuha, J.; Lejju, J.B.; Rugunda, G.K.; Bazira, J. The Physico-Chemical Quality of Effluents of Selected Sewage Treatment Plants Draining into River Rwizi, Mbarara Municipality, Uganda. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2019, 11, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okot-Okumu, J.; Nyenje, R. Municipal solid waste management under decentralisation in Uganda. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, B.; Barden, R.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. A review on emerging contaminants in wastewaters and the environment: Current knowledge, understudied areas and recommendations for future monitoring. Water Res. 2015, 72, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komakech, A.J.; Banadda, N.E.; Kinobe, J.R.; Kasisira, L.; Sundberg, C.; Gebresenbet, G.; Vinnerås, B. Characterization of municipal waste in Kampala, Uganda. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2014, 64, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasswa, J.; Schluep, M.; Empa.e-Waste Assessment in Uganda. A Situational Analysis of E-Waste Management and Generation with Special Emphasis on Personal Computers 6 May 2018. Available online: https://docplayer.net/22226699-E-waste-assessment-in-uganda.html (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Breivik, K.; Gioia, R.; Chakraborty, P.; Zhang, G.; Jones, K.C. Are reductions in industrial organic contaminants emissions in rich countries achieved partly by export of toxic wastes? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9154–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwematsiko, R.; Oporia, F.; Nabirye, J.; Halage, A.A.; Musoke, D.; Buregyeya, E. Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Electronic Waste Management among Consumers in Kampala, Uganda. J. Environ. Public Health 2021, 2021, 3846428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schluep, M.; Wasswa, J.; Kreissler, B.; Nicholson, S. E-waste generation and management in Uganda. In Proceedings of the 19th Waste Management Conference of the IWMSA (WasteCon2008), Durban, South Africa, 6–10 October 2008; pp. 510–515, ISBN 978-0-620-40434-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ssebugere, P.; Kiremire, B.T.; Henkelmann, B.; Bernhöft, S.; Kasozi, G.N.; Wasswa, J.; Schramm, K.W. PCDD/Fs and dioxin-like PCBs in fish species from Lake Victoria, East Africa. Chemosphere 2013, 92, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Steiniche, T.; Romanak, K.A.; Johnson, E.; Quirós, R.; Mutegeki, R.; Wasserman, M.D.; Venier, M. Atmospheric Occurrence of Legacy Pesticides, Current Use Pesticides, and Flame Retardants in and around Protected Areas in Costa Rica and Uganda. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6171–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaitan, J.O.; Anyakora, C.; Adetifa, I.O.; Adepoju-Bello, A.A. A Screening for Selected Human Pharmaceuticals in Water Using SPE-HPLC, Ogun State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Pharm. Sci. Pharm. 2017, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- K’oreje, K.O.; Kandie, F.J.; Vergeynst, L.; Abira, M.A.; Van Langenhove, H.; Okoth, M.; Demeestere, K. Occurrence, fate and removal of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and pesticides in wastewater stabilization ponds and receiving rivers in the Nzoia Basin, Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 637–638, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhaj, D.; Athmouni, K.; Jerbi, B.; Kallel, M.; Ayadi, H.; Zhou, J.L. Estrogenic compounds in Tunisian urban sewage treatment plant: Occurrence, removal and ecotoxicological impact of sewage discharge and sludge disposal. Ecotoxicology 2016, 25, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbuna, C.; Amadi, C.N.; Patrick-Iwuanyanwu, K.C.; Ezzat, S.M.; Awuchi, C.G.; Ugonwa, P.O.; Orisakwe, O.E. Emerging pollutants in Nigeria: A systematic review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 85, 103638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansa-Otim, J.S.; Lutaaya, P.; Kamya, T.; Lubega, S.M. Analysis of mobile phone e-waste management for developing countries: A case of Uganda. In Proceedings of the 4th International ICST Conference, AFRICOMM 2012, Yaounde, Cameroon, 12–14 November 2012; pp. 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kerebba, N.; Ssebugere, P.; Kwetegyeka, J.; Arinaitwe, K.; Wasswa, J. Concentrations and sources apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments from the Uganda side of Lake Victoria. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2017, 19, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimized digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twinomucunguzi, F.R.B.; Nyenje, P.M.; Kulabako, R.N.; Semiyaga, S.; Foppen, J.W.; Kansiime, F. Emerging organic contaminants in shallow groundwater underlying two contrasting peri-urban areas in Uganda. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukonzo, J.K.; Namuwenge, P.M.; Okure, G.; Mwesige, B.; Namusisi, O.K.; Mukanga, D. Over-the-counter suboptimal dispensing of antibiotics in Uganda. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2013, 6, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Nsubuga, F.B.; Kansiime, F.; Okot-Okumu, J. Pollution of protected springs in relation to high and low density settlements in Kampala—Uganda. Phys. Chem. Earth 2004, 29, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntirushize, B.; Wasswa, J.; Ntambi, E.; Adaku, C. Analysis for Organochlorine Pesticide Residues in Honey from Kabale District, South-Western Uganda. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2019, 10, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinaitwe, K.; Kiremire, B.T.; Muir, D.C.G.; Fellin, P.; Li, H.; Teixeira, C.; Mubiru, D.N. Legacy and currently used pesticides in the atmospheric environment of Lake Victoria, East Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 543, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sserunjoji, J.M.S. A Study of Organochlorine Insecticide Residues in Uganda, with Special Reference to Dieldrin and DDT. In Comparative Studies of Food and Environmental Contamination; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 1974; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Staudacher, P.; Fuhrimann, S.; Farnham, A.; Mora, A.M.; Atuhaire, A.; Niwagaba, C.; Stamm, C.; Eggen, R.I.L.; Winkler, M.S. Comparative Analysis of Pesticide Use Determinants Among Smallholder Farmers From Costa Rica and Uganda. Environ. Health Insights 2020, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandiga, S.O. Use and distribution of organochlorine pesticides. The future in Africa. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.; Kishimba, M.A. Pesticide residues in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and Nile perch (Lates niloticus) from Southern Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 140, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mukiibi, S.; Nyanzi, S.A.; Kwetegyeka, J.; Olisah, C.; Taiwo, A.M.; Mubiru, E.; Tebandeke, E.; Matovu, H.; Odongo, S.; Abayi, J.J.M.; et al. Organochlorine pesticide residues in Uganda’s honey as a bioindicator of environmental contamination and reproductive health implications to consumers. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 214, 112094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssebugere, P.; Kiremire, B.T.; Kishimba, M.; Wandiga, S.O.; Nyanzi, S.A.; Wasswa, J. DDT and metabolites in fish from Lake Edward, Uganda. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejobi, F.; Kanja, L.W.; Kyule, M.N.; Müller, P.; Krüger, J.; Nyeko, J.H.P.; Latigo, A.A.R. Organochlorine pesticide residues in cow’s milk in Uganda. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1996, 56, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssebugere, P.; Wasswa, J.; Mbabazi, J.; Nyanzi, S.A.; Kiremire, B.T.; Marco, J.A.M. Organochlorine pesticides in soils from south-western Uganda. Chemosphere 2010, 78, 1250–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, M.; Birnbaum, L.S.; Denison, M.; De Vito, M.; Farland, W.; Feeley, M.; Fiedler, H.; Hakansson, H.; Hanberg, A.; Haws, L.; et al. The 2005 World Health Organization reevaluation of human and mammalian toxic equivalency factors for dioxins and dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 93, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbabazi, J.; Twinomuhwezi, H.; Wasswa, J.; Ntale, M.; Mulongo, G.; Kwetegyeka, J.; Schrǿder, K.H. Speciation of heavy metals in water from the Uganda side of Lake Victoria. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 67, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twinamatsiko, R.; Mbabazi, J.; Twinomuhwezi, H. Toxic Metal Levels in Food Crops Grown From Dump-Sites Around Gulu Municipality, Northern Uganda. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Technol. 2016, 1, 22–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mbabazi, J.; Bakyayita, G.; Wasswa, J.; Muwanga, A.; Twinomuhwezi, H.; Kwetegyeka, J. Variations in the contents of heavy metals in arable soils of a major urban wetland inlet drainage system of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Lakes Reserved. Res. Manag. 2010, 15, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, K.I.; Natabo, P.C.; Namubiru, S.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Tamale, A.; Bamaiyi, P.H. Food Safety Analysis of Milk and Beef in Southwestern Uganda. J. Environ. Public Health 2018, 2018, 1627180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namuhani, N.; Cyrus, K. Soil Contamination with Heavy Metals around Jinja Steel Rolling Mills in Jinja Municipality, Uganda. J. Health Pollut. 2015, 5, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongi, R.; Chove, L. Heavy metal contamination in cocoyam crops and soils in countries around the Lake Victoria basin (Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya). Tanzan. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 19, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Nabulo, G.; Oryem-Origa, H.; Diamond, M. Assessment of lead, cadmium, and zinc contamination of roadside soils, surface films, and vegetables in Kampala City, Uganda. Environ. Res. 2006, 101, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumwine, J.; Nassanga, H.B.; Kateregga, J.; Tumwine, G.; Kitimbo, J. An Experimental Study Determining Levels of Lead Contamination of Dioscorea spp. (Yams) from Selected Regions of Kampala Capital City, Uganda. Stud. J. Health Res. Afr. 2022, 3, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Mpewo, M.; Kizza-Nkambwe, S.; Kasima, J.S. Heavy metal and metalloid concentrations in agricultural communities around steel and iron industries in Uganda: Implications for future food systems. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2023, 35, 2226344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, W.; Njenga, H. Investigation of Levels of Some Selected Heavy Metals in Raw Bovine Milk from Oyam District, Uganda and Estimation of Potential Health Risks. Am. J. Appl. Ind. Chem. 2007, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kasozi, K.I.; Otim, E.O.; Ninsiima, H.I.; Zirintunda, G.; Tamale, A.; Ekou, J.; Musoke, G.H.; Muyinda, R.; Matama, K.; Mujinya, R.; et al. An analysis of heavy metals contamination and estimating the daily intakes of vegetables from Uganda. Toxicol. Res. Appl. 2021, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrimann, S.; Stalder, M.; Winkler, M.S.; Niwagaba, C.B.; Babu, M.; Masaba, G.; Kabatereine, N.B.; Halage, A.A.; Schneeberger, P.H.H.; Utzinger, J.; et al. Microbial and chemical contamination of water, sediment, and soil in the Nakivubo wetland area in Kampala, Uganda. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagumira, A.; Biira, S.; Amabayo, E.B. Concentrations and human health risk assessment of selected heavy metals in soils and food crops around Osukuru phosphate mine, Tororo District, Uganda. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 2042–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, K.I.; Namubiru, S.; Kamugisha, R.; Eze, E.D.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Ssempijja, F.; Okpanachi, A.O.; Kinyi, H.W.; Atusiimirwe, J.K.; Suubo, J.; et al. Safety of Drinking Water from Primary Water Sources and Implications for the General Public in Uganda. J. Environ. Public Health 2019, 2019, 7813962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, K.I.; Hamira, Y.; Zirintunda, G.; Alsharif, K.F.; Altalbawy, F.M.A.; Ekou, J.; Tamale, A.; Matama, K.; Ssempijja, F.; Muyinda, R.; et al. Descriptive Analysis of Heavy Metals Content of Beef From Eastern Uganda and Their Safety for Public Consumption. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 592340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssempijja, F.; Iceland Kasozi, K.; Daniel Eze, E.; Tamale, A.; Ewuzie, S.A.; Matama, K.; Ekou, J.; Bogere, P.; Mujinya, R.; Musoke, G.H.; et al. Consumption of Raw Herbal Medicines Is Associated with Major Public Health Risks amongst Ugandans. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 8516105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.R.; Susan, T.B. Water contamination with heavy metals and trace elements from Kilembe copper mine and tailing sites in Western Uganda; implications for domestic water quality. Chemosphere 2017, 169, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahimbisibwe, O.; Byamugisha, D.; Mukasa, P.; Omara, T.; Ntambi, N. Leaching of Lead, Chromium and Copper into Drinks Placed in Plastic Cups at Different Conditions. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2022, 13, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baluka, S.A.; Schrunk, D.; Imerman, P.; Kateregga, J.N.; Camana, E.; Wang, C.; Rumbeiha, W.K. Mycotoxin and metallic element concentrations in peanut products sold in Ugandan markets. Cogent Food Agric. 2017, 3, 1313925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakamwesiga, H.; Mugisha, W.; Kisira, Y.; Muwanga, A. An Assessment of Air and Water Pollution Accrued from Stone Quarrying in Mukono District, Central Uganda. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2022, 10, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omara, T.; Karungi, S.; Kalukusu, R.; Nakabuye, B.V.; Kagoya, S.; Musau, B. Mercuric pollution of surface water, superficial sediments, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis nilotica Linnaeus 1758 [Cichlidae]) and yams (Dioscorea alata) in auriferous areas of Namukombe stream, Syanyonja, Busia, Uganda. PeerJ 2019, 2019, e7919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muwanga, A.; Barifaijo, E. Impact of industrial activities on heavy metal loading and their physicochemical effects on wetlands of Lake Victoria basin (Uganda). Afr. J. Sci. Technol. 2010, 7, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ssebugere, P.; Kiremire, B.T.; Henkelmann, B.; Bernhöft, S.; Wasswa, J.; Kasozi, G.N.; Schramm, K.W. PCDD/Fs and dioxin-like PCBs in surface sediments from Lake Victoria, East Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 454–455, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abayi, J.J.M.; Gore, C.T.; Nagawa, C.; Bandowe, B.A.M.; Matovu, H.; Mubiru, E.; Ngeno, E.C.; Odongo, S.; Sillanpää, M.; Ssebugere, P. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments and fish species from the White Nile, East Africa: Bioaccumulation potential, source apportionment, ecological and health risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaaya, A.N.; Harris, C.; Eigel, W. Peanut Aflatoxin Levels on Farms and in Markets of Uganda. Peanut Sci. 2006, 33, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuret, J.; Musinguzi, G.; Mukama, T.; Halage, A.A.; Natigo, A.K.; Ssempebwa, J.C.; Wang, J.S. Aflatoxin contamination of selected staple foods sold for human consumption in Kampala markets, Uganda. J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 16, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukwago, F.B.; Mukisa, I.M.; Atukwase, A.; Kaaya, A.N.; Tumwebaze, S. Mycotoxins contamination in foods consumed in Uganda: A 12-year review (2006-18). Sci. Afr. 2019, 3, e00054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitya, D.; Bbosa, G.S.; Mulogo, E. Aflatoxin levels in common foods of South Western Uganda: A risk factor to hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2010, 19, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaaya, A.N.; Eboku, D. Mould, and aflatoxin contamination of dried cassava chips in Eastern Uganda: Association with traditional processing and storage practices. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 10, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echodu, R.; Maxwell Malinga, G.; Moriku Kaducu, J.; Ovuga, E.; Haesaert, G. Prevalence of aflatoxin, ochratoxin and deoxynivalenol in cereal grains in northern Uganda: Implication for food safety and health. Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wokorach, G.; Landschoot, S.; Anena, J.; Audenaert, K.; Echodu, R.; Haesaert, G. Mycotoxin profile of staple grains in northern Uganda: Understanding the level of human exposure and potential risks. Food Control 2021, 122, 107813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onen, P.; Watmon, J.; Omara, T.; Ocira, D. Aflatoxin content and health risks associated with consumption of some herbal products sold in Kampala, Uganda. Fr. Ukr. J. Chem. 2021, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sserumaga, J.P.; Ortega-Beltran, A.; Wagacha, J.M.; Mutegi, C.K.; Bandyopadhyay, R. Aflatoxin-producing fungi associated with pre-harvest maize contamination in Uganda. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 313, 108376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taligoola, H.K.; Ismail, M.A.; Chebon, S.K. Toxigenic fungi, and aflatoxins associated with marketed rice grains in Uganda. J. Basic Appl. Mycol. 2010, 1, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Atukwase, A.; Muy, C.; Kaaya, A.N. Potential for fumonisin production by strains of Gibberella fujikurioi species comples isolated from maize produced in Uganda. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 12, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namulawa, V.T.; Mutiga, S.; Musimbi, F.; Akello, S.; Ngángá, F.; Kago, L.; Kyallo, M.; Harvey, J.; Ghimire, S. Assessment of fungal contamination in fish feed from the Lake Victoria Basin, Uganda. Toxins 2020, 12, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atukwase, A.; Kaaya, A.N.; Muyanja, C.; Vismer, H.; Rheeder, J.P. Diversity of Gibberella fujikuroi Species Complex Isolated from Maize Produced in Uganda. Int. J. Plant Pathol. 2011, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Waliyar, F.; Kumar, P.L.; Ntare, B.R.; Diarra, B. And Kodio, O. Pre- and post-harvest management of aflatoxin contamination in peanuts. In Mycotoxins: Detection Methods, Management, Public Health, and Agricultural Trade; Leslie, J.F., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Biira, S.; Ochom, P.; Oryema, B. Evaluation of radionuclide concentrations and average annual committed effective dose due to medicinal plants and soils commonly consumed by pregnant women in Osukuru, Tororo (Uganda). J. Environ. Radioact. 2021, 227, 106460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Background Radiations and Radon Concentrations in the Dormitories of Secondary Schools in Otuke District, Uganda. J. Radiat. Nucl. Appl. 2020, 5, 211–218. [CrossRef]

- Biira, S.; Kisolo, A.W.; D’ujanga, F.M. Concentration levels of radon in mines, industries, and dwellings in selected areas of Tororo and Busia districts, Eastern Uganda. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2014, 5, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, T.E.R.; Jurua, E.; Oriada, R.; Mugaiga, A.; Enjiku, B. Determination of Natural Radioactivity Levels due to Mine Tailings from Selected Mines in Southwestern Uganda. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 6, 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- Egessa, R.; Nankabirwa, A.; Ocaya, H.; Pabire, W.G. Microplastic pollution in surface water of Lake Victoria. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nshemereirwe, A.; Zewge, F.; Malambala, E. Evaluation of formation and health risks of disinfection by-products in drinking water supply of Ggaba waterworks, Kampala, Uganda. J. Water Health 2022, 20, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiwango, R.; Bainomugisha, E.; Kivunike, F.; Kateete, D.P.; Jjingo, D. Air pollution and mobility patterns in two Ugandan cities during COVID-19 mobility restrictions suggest the validity of air quality data as a measure for human mobility. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 34856–34871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, S.; Parks, B.; Anguma, S.; Meng, Q. Spatio-temporal variation in the concentration of inhalable particulate matter (PM10) in Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiggundu, A.T. Capabilities and gaps assessments of urban air quality management in Uganda. Indones. J. Geogr. 2015, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kinobe, J.R.; Niwagaba, C.B.; Gebresenbet, G.; Komakech, A.J.; Vinnerås, B. Mapping out the solid waste generation and collection models: The case of Kampala City. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2015, 65, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogoi, A.; Mazumder, P.; Tyagi, V.K.; Tushara Chaminda, G.G.; An, A.K.; Kumar, M. Occurrence and fate of emerging contaminants in water environment: A review. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 6, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Zambello, E. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in urban wastewater: Removal, mass load and environmental risk after a secondary treatment-A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, M.; Sabater, S.; Elosegi, A.; Barceló, D. Emerging Contaminants in River Ecosystem: Occurrence and Effects Under Multiple Stress. In The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 46. [Google Scholar]

- Hossein, M. Toxicological aspects of emerging contaminants. In Emerging and Eco-Friendly Approaches for Waste Management; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2019; pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Munschy, C.; Vigneau, E.; Bely, N.; Héas-Moisan, K.; Olivier, N.; Pollono, C.; Hollanda, S.; Bodin, N. Legacy and emerging organic contaminants: Levels and profiles in top predator fish from the western Indian Ocean in relation to their trophic ecology. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landecker, H. Antimicrobials before antibiotics: War, peace, and disinfectants. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanigan, D.; Truong, L.; Simonich, M.; Tanguay, R.; Westerhoff, P. Zebrafish embryo toxicity of 15 chlorinated, brominated, and iodinated disinfection by-products. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 58, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omara, T. Aflatoxigenic contamination of freshly harvested white maize (Zea mays L.) from some selected Ugandan districts. PeerJ Prepr. 2019, 7, e27888v1. [Google Scholar]

- Järup, L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaganda, A.; Spencer, A.; Orem, J.; Mpamani, C.; Wabinga, H.; Nambooze, S.; Kiwanuka, G.N.; Atwine, R.; Gemmell, I.; Jones, A.; et al. Estimating cancer incidence in Uganda: A feasibility study for periodic cancer surveillance research in resource limited settings. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Zhang, L.; Lei, J.; Zong, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z. Overview of emerging contaminants and associated human health effects. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 404796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivy, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Dey, S.; Gupta, K.; Dey, A.; Sharma, P. Effects of microplastics and arsenic on plants: Interactions, toxicity and environmental implications. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steensberg, J. Health effects of chemical products. Ecol. Dis. 1982, 1, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Environmental management in Uganda: A reflection on the role of NEMA and its effectiveness in implementing Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) of the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area (GKMA). J. Adv. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 5, 1–13.

- NEMA. 2016. National Implementation Plan II for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2016–2025). Available online: https://www.informea.org/en/national-implementation-plan-ii-nipii-stockholm-convention-persistent-organic-pollutants-pops-2016 (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Sánchez-Polo, M.; Ferro-García, M.Á.; Prados-Joya, G.; Ocampo-Pérez, R. Pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants and their removal from water. A review. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1268–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.; Rosal, R.; Perdigón-Melón, J.A.; Mezcua, M.; Agüera, A.; Hernando, M.D.; Letón, P.; Fernández-Alba, A.R.; García-Calvo, E. Ozone-based technologies in water and wastewater treatment. In Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5, pp. 127–175, Part S/2. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, M.O.; Moreira, N.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Silva, A.M.T. Occurrence and removal of organic micropollutants: An overview of the watch list of EU Decision 2015/495. Water Res. 2016, 94, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, W.; Egea, E. Health and environmental risks associated with emerging pollutants and novel green processes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 6085–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egea-Corbacho Lopera, A.; Gutiérrez Ruiz, S.; Quiroga Alonso, J.M. Removal of emerging contaminants from wastewater using reverse osmosis for its subsequent reuse: Pilot plant. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 29, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, D.P.; Kirpalani, D.M. Advancement in treatment of wastewater: Fate of emerging contaminants. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 97, 2621–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, J.G.; Velizarov, S.; Reis, M.A. Membrane bioreactors for the removal of anionic micropollutants from drinking water. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004, 15, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Kakade, A.; Yu, Z.; Khan, A.; Liu, P.; Li, X. Anaerobic membrane bioreactors for treatment of emerging contaminants: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M. Removal of heavy metals from the environment by biosorption. Eng. Life Sci. 2004, 4, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Lee, D. Bisphenol A removal by a membrane bioreactor. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Guerra, P.; Shah, A.; Parsa, M.; Alaee, M.; Smyth, S.A. Removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in a membrane bioreactor wastewater treatment plant. Water Sci. Technol. 2014, 69, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, S.A.; Austern, B.M.; Eralp, A.E.; Wise, R.H. Comparative removal of toxic pollutants by six wastewater treatment processes. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1986, 58, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, F.M.; Amal, R.; Luketina, D. Removal of particles using coagulation and flocculation in a dynamic separator. Powder Technol. 1996, 88, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micek, A.; Jóźwiakowski, K.; Marzec, M.; Listosz, A.; Malik, A. Efficiency of pollution removal in preliminary settling tanks of household wastewater treatment plants in the Roztocze National Park. J. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 21, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrete Velasco, A.; Ramseier Gentile, S.; Zimmermann, S.; Le Coustumer, P.; Stoll, S. Contamination and removal efficiency of microplastics and synthetic fibres in a conventional drinking water treatment plant in Geneva, Switzerland. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortula, M.M.; Abdelrahman, M.; Tatan, B. Comparative Evaluation of Membrane Filtration on the Tertiary Treatment of Synthetic Secondary Effluent. Separations 2022, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y. Novel cyclodextrin-based adsorbents for removing pollutants from wastewater: A critical review. Chemosphere 2020, 241, 125043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavoshani, A.; Hashemi, M.; Amin, M.M.; Ameta, S.C. Micropollutants and Challenges: Emerging in the Aquatic Environments and Treatment Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 35–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gorito, A.M.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Almeida, C.M.R.; Silva, A.M.T. A review on the application of constructed wetlands for the removal of priority substances and contaminants of emerging concern listed in recently launched EU legislation. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wen, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Bürgmann, H. New insight into effect of antibiotics concentration and process configuration on the removal of antibiotics and relevant antibiotic resistance genes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Li, Y.; Song, Q.; Wang, L.; Luo, T.; Gao, C.; Liu, L.; Yang, S. Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) by Free Radicals in Advanced Oxidation Processes. Materials 2022, 15, 8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghime, D.; Ghosh, P. Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Powerful Treatment Option for the Removal of Recalcitrant Organic Compounds. In Advanced Oxidation Processes—Applications, Trends, and Prospects; In Bustillo-Lecompte, C., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- López-Montilla, J.C.; Pandey, S.; Shah, D.O.; Crisalle, O.D. Removal of non-ionic organic pollutants from water via liquid-liquid extraction. Water Res. 2005, 39, 1907–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Mu, S.; Li, Q. Extraction and separation of petroleum pollutants from oil-based drilling cuttings using methanol/n-hexane solvent. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahiem, E.E.; Al-Maghrabi, M.N.; Mobarki, A.R. Removal of organic pollutants from industrial wastewater by applying photo-Fenton oxidation technology. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S1674–S1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Fard, M.S. A critical review in Fenton-like approach for the removal of pollutants in the aqueous environment. Environ. Chall. 2022, 7, 100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.E.; de Paz Carmona, H.; Gutiérrez, M.; Esparza, P. Photocatalytic Removal of Water Emerging Pollutants in an Optimized Packed Bed Photoreactor Using Solar Light. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Ghatak, H.R.; Ahuja, S.M. A review on photocatalytic remediation of environmental pollutants and H2 production through water splitting: A sustainable approach. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 19, 100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, J.; Nuutinen, I.; Niittynen, M.; Hokajärvi, A.M.; Pitkänen, T.; Antikainen, E.; Miettinen, I.T. Presence and reduction of anthropogenic substances with UV light and oxidizing disinfectants in wastewater—A case study at Kuopio, Finland. Water 2021, 13, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, D.; Cai, S.; Tan, Y.; Liao, J.; Fang, Y. Dyes removal by composite membrane of sepiolite impregnated polysulfone coated by chemical deposition of tea polyphenols. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 156, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, W.; Nan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gao, C.; Chen, X. Fabrication and characterization of a high performance polyimide ultrafiltration membrane for dye removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 562, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Diehl, A.; Lewandowski, A.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Baker, T. Removal efficiency of micro- and nanoplastics (180 nm–125 μm) during drinking water treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PureTec. Puretec Industrial Water | What Is Reverse Osmosis? [Internet]. Puretecwater.Com. 2022. Available online: https://puretecwater.com/reverse-osmosis/what-is-reverse-osmosis#recovery (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Cevallos-Mendoza, J.; Amorim, C.G.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.M.; Montenegro, M.d.C.B.S.M. Removal of Contaminants from Water by Membrane Filtration: A Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category of CoC | Description | Components | Persistence and Bioaccumulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals | Medicinal compounds, including prescription and over-the-counter drugs, enter the environment through human excretion and wastewater. | Antibiotics, Analgesics, Hormones, Antidepressants, Beta-Blockers, Diuretics, Antihypertensive, Fibrate, and Antiparasitic | Low to Medium Persistence, some are bioaccumulative in zoobenthos |

| Pesticides | Chemical substances used to control pests in agriculture can leach into soil and water, impacting non-target organisms. | Insecticides, Herbicides, Fungicides, and Rodenticides | Medium to High Persistence, some are bioaccumulative such as the cases of Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) | Organic compounds that resist degradation, such as certain pesticides and industrial chemicals, with potential long-range transport effects. | Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs), Dioxins, and Furans, among others | High persistence and Bioaccumulative |

| Personal Care Products | Chemicals found in cosmetics, shampoos, soaps, and perfumes can be washed into water bodies and contribute to water pollution. | Fragrances, UV Filters, Preservatives, and Surfactants | Low to Medium Persistence |

| Heavy metals | Metallic elements like lead, mercury, cadmium, and chromium can accumulate in the environment and pose health risks to living organisms. | Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Cadmium (Cd), Chromium (Cr), Nickle (Ni) among others | Medium to High Persistence, some are bioaccumulative |

| Hydrocarbon Compounds | Organic compounds derived from petroleum, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are often associated with oil spills. | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs), and Benzene | Low to Medium Persistence, Bioaccumulative |

| Biotoxins–Mycotoxins | Toxins are produced by organisms like fungi (mycotoxins) and harmful algae, which can contaminate water and food sources, posing health risks. | Aflatoxins, Ochratoxins, and Fusarium Toxins | Low Persistence, bioaccumulative in humans and animals |

| Radionuclides and Electromagnetic radiations | Radioactive elements and non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation that can impact human health and the environment. | Uranium (U), Thorium (Th), 40-K and Radon (Rn), Radiofrequency (RF), Microwaves, Electromagnetic Fields, | Low to High persistence |

| Other Contaminants of concern | Various emerging contaminants, like flame retardants and nanomaterials, whose impacts on the environment and health are under investigation. | Flame Retardants, and Nanomaterials, | Persistent and highly Bioaccumulative, atmospheric deposition |

| Microplastics | Tiny plastic particles result from the breakdown of larger plastic waste, which can be ingested by organisms and enter the food chain. | Microplastic particles, and Microfibers, | Low to Medium Persistence, atmospheric deposition |

| Disinfection byproducts | Chemical compounds formed when disinfectants like chlorine react with organic matter in water, potentially leading to health risks. | Trihalomethanes (THMs) | Low to Medium Persistence |

| Particulates | Tiny solid particles or liquid droplets suspended in the air can have adverse health effects when inhaled by humans and animals. | PM2.5 (Fine Particulate Matter), PM10 (Coarse Particulate Matter), Gases, Sulphur dioxide (SO2), Ozone (O3), and Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) | Low Persistence |

| Categories of CoC | Classes | CoC (s) | Use/Application | Sampling Matrix | Detected Levels | Place of Study | Detection Periods | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals | Antibiotics | Sulfamethoxazole | Pharmaceutical | Wastewater Effluents, Sediments, Soil, Surface Waters | 1–5600 ngL−1 | Murchison Bay on L. Victoria and Bugolobi wastewater treatment plant, Kampala, Uganda | 2020–2022 | [30,41,42] |

| Trimethoprim | Pharmaceutical | 1300–22,600 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Sulfamethazine | Pharmaceutical | 2.4–50 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Sulfacetamide | Pharmaceutical | 0.8–13 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Tetracycline | Pharmaceutical | 3–70 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Erythromycin | Pharmaceutical | 10–66 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Carbamazepine | Pharmaceutical | 5–72 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Oxytetracycline | Pharmaceutical | 17–300 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Tetracycline | Pharmaceutical | 2.7–70 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Erythromycin | Pharmaceutical | 10–66 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Azithromycin | Pharmaceutical | 14–60 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | Pharmaceutical | 2.0–41 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Levofloxacin | Pharmaceutical | 1.8–29 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Norfloxacin | Pharmaceutical | 1.9–26 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Enoxacin | Pharmaceutical | 5.9–51 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Ampicillin | Pharmaceutical | Wastewater Effluents, Ground Water, Runoffs | 1350 ngL−1 | Bwaise Wobulenzi city suburbs, Kampala, Uganda | 2013–2022 | [42,69,70] | ||

| Chlortetracycline | Pharmaceutical | 394 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | Pharmaceutical | 340 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Enrofloxacin | Pharmaceutical | 17 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Metacycline | Pharmaceutical | 17 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Nalidixic acid | Pharmaceutical | 2340 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Oxytetracycline | Pharmaceutical | 17 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Penicillin G (benzylpenicillin) | Pharmaceutical | 800 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Sulfathiazole | Pharmaceutical | 140 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Tetracycline | Pharmaceutical | 47.3 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Analgesic/Anti-inflammatory | Ibuprofen | Pharmaceutical | Wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) Effluents, Runoffs, sewer channel wastewater | 5.9–780 ngL−1 | Nakivubo sewer channel, Murchison Bay on L. Victoria and Bugolobi wastewater treatment plant, Uganda | 2020 | [30,41] | |

| Diclofenac | Pharmaceutical | 100–500 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Acetaminophen | Pharmaceutical | 1.6–27 ng/L | ||||||

| Antiepileptics/antidepressant | Carbamazepine | Pharmaceutical | 200–1300 ngL−1 346.496 µgL−1 *CEC | |||||

| Beta-Blockers | Atenolol | Pharmaceutical | 24–380 ngL−1 | |||||

| Metoprolol | Pharmaceutical | 0.4–21 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Diuretics | Furosemide | Pharmaceutical | 160–1300 ngL−1 | |||||

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Pharmaceutical | 230–1350 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Antihypertensive | Losartan | Pharmaceutical | 100–160 ngL−1 | |||||

| Fibrate | Gemfibrozil | Pharmaceutical | 190–800 ngL−1 | |||||

| Antiparasitic | Pyrimethamine | Pharmaceutical | 8.4–14.0 ngL−1 | |||||

| Pesticides | Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) | Endosulfan sulfate | Herbicide, insecticides and fungicides | Air, sediment, and surface water samples | 0.82–5.62 µg kg−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in 2011) | Murchison, Waiya, Thurston Bays, and Napoleon Gulf on the Ugandan side of L. Victoria | 2004–2022 | [23,31,34,39,45,49,52,71,72,73,74] |

| Aldrin | Herbicide, insecticide | 0.22–15.96 µg kg−1 d.w (MRL = 0.1 mg kg−1) (Banned for all users in 2001) | ||||||

| Dieldrin | Soil insecticide and for control of mosquitoes. | 0.94–7.18 µg kg−1 d.w (MRL = 0.1 mg kg−1) (Banned for all users in 2001) | ||||||

| Lindane | Insecticide | 7–11.4 μg kg−1 d.w. (MRL = 0.5 mg kg−1) | ||||||

| Chlordane | Insecticide | 3.82–35.6 pgm−3 (Banned for all users in 2001) | ||||||

| Hexachlorocyclohexanes | Insecticide | 3.72–81.8 pg m−3 (Banned for all users in 2009) | ||||||

| Heptachlor | Insecticide | 0.81 μg kg−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in 2001) | ||||||

| Heptachlor epoxide | Insecticide. Used for fire ant control in power transformers | 3.19 μg kg−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in 2001) | ||||||

| p, p′- dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) | Insecticides | 0.11–3.59 μg kg−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in | ||||||

| p, p′-DDD | 0.38–4.02 μg kg−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in | |||||||

| p, p′-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) | 0.04–1.46 μg kg−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in | |||||||

| o, p′-DDE | 0.07–2.72 μg kg−1 d.w. | |||||||

| o, p′-DDT | 0.01–1.63 μg kg−1 d.w. | |||||||

| Total Endosulfan | Isomer of Endosulfan. Insecticide and acaricide | 12.3–282 pg m−3 (Banned for all users in 2011) | Air and water samples of Lake Victoria Northern shore watershed, areas of Kakira and Entebbe, Uganda | 2006–2022 | [31,45,49,69,72,73,75,76,77,78] | |||

| Total DDT-related compounds | Insecticide used in agriculture | 22.8–130 pg m−3 (Banned in 2001, production for the specific uses) | ||||||

| Endosulfan sulphate | Insecticide and acaricide | 0.82–5.62 μg kg−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in 2011) | ||||||

| α-Endosulfan | 7.59 and 6.00 μg kg−1 (MRL = 0.1 mg kg−1) (Banned for all users 2011) | Napoleon Gulf on L. Victoria, Uganda | 2004–2022 | [34,49,73,79] | ||||

| p, p′-1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis-(4-chlorophenyl) ethylene (p, p′-DDE) | Insecticide | Air, Surface waters, Fish Tissues | 6.10 and 3.44 μg kg−1 | Napoleon Gulf on L. Victoria, Uganda | 2006–2010 | [31,45,77] | ||

| p, p′-1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis-(4-chlorophenyl) ethane (p, p′-DDT) | 7.34 and 4.30 μg kg−1 (MRL = 0.1 mg kg−1) | |||||||

| ∑DDTs | 503.6 μg kg−1 d.w. | Abandoned pesticide store in Masindi district in western Uganda | 2020 | [78] | ||||

| Endosulfans | 1.55 μg kg−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in 2011) | |||||||

| p, p’DDE | 125 mg/kg | Kampala and Iganga districts in Uganda | 1996–2011 | [44,80] | ||||

| Dieldrin | 123 mg/kg | |||||||

| p, p’DDD | 24 mg/kg | |||||||

| p, p, DDT | 13 mg/kg | |||||||

| o, p’DDT | 23 mg/kg | |||||||

| α-hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) | 54 mg/kg (Banned for all users in 2009) | |||||||

| β-HCH | 10 mg/kg (Banned for all users in 2009) | |||||||

| Total Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (ΣDDTs) | 22.8–130 pg/m3 | Kakira and Entebbe, northern shore of L. Victoria, Uganda | 2016 | [73] | ||||

| Total hexachlorocyclohexanes (ΣHCHs) | 3.72–81.8 pg/m3 | |||||||

| Total Endosulfan (ΣEndo) | 12.3–282 pg/m3 | |||||||

| Carbamates | Carbofuran | Insecticide | Air, Surface waters, Fish Tissues | 83.3 pg/m3 | Air samples from Kakira and Entebbe, northern shore of L. Victoria, Uganda | 2010–2019 | [72,78,81] | |

| Organophosphates (OPPs) | Chlorpyrifos | 93.5 ng/m3 | ||||||

| Chlorthalonil | Fungicide | <0.10–24.0 pg m−3 | ||||||

| Metribuzin | Herbicide | <0.02–0.53 ng m−3 | ||||||

| Trifluralin | 0.02–0.32 pg m−3 | |||||||

| Malathion | Insecticide | <0.08–193 pg m−3 | ||||||

| Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) | Brominated Flame Retardants | polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) | Are used as coolants and lubricants in transformers, capacitors, and other electrical equipment | Sediment samples | 9.84 pg g−1 dry weight (Banned for all users in 2001) | Napoleon Gulf and Thurston Bay on the northern shore of L. Victoria, Uganda | 2013 | [46] |

| Chlorinated Flame Retardants | Dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) | 136 pg g−1 dw (Banned for all users in 2001) | 2006–2021 | [40,46,60,82] | ||||

| polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins/furans (PCDD/Fs) | 44.1 pg g−1 d.w. 0.07–5.53 pg Toxic Equivalent Factors (TEQ) g−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in 2001) | 2006–2021 | [40,60,82] | |||||

| polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs) | 0.07–5.61 pg g−1 d.w. 0.01–0.23 pg TEQ g−1 d.w. (Banned for all users in 2001) | 2006–2021 | [40,60,82] | |||||

| Organochlorine pesticides | Pymetrozine | Pesticide | Edible Insects | 0.02 pg g−1 d.w. | Ugandan districts | 2022 | [39] | |

| Methabenzthiazuron | 0.08 pg g−1 d.w. | |||||||

| Metazachlor | 1.4 ± 0.03 pg g−1 d.w. | |||||||

| Fenimorph | 0.04 ± 0.03 pg g−1 d.w. | |||||||

| Fludioxonil | Fungicide | 0.29 pg g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Metalaxyl | 0.01 ± 0.01 pg g−1 d.w. | |||||||

| Organophosphorus flame retardants (OPFRs) | Tricresyl phosphate | Used as a plasticizer | Waters, sediments, and soil samples | 25–8100 ngL−1 | Napoleon gulf, Murchison, Waiya, Entebbe, and Thurston bays, Uganda | 2006–2021 | [31,43,44,49,72,74,76,77,78] | |

| Tris-(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP) | Widely used as a plasticizer, fire retardant, and solvent | 24–6500 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Triphenyl phosphate (TPP) | 54–4300 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Tris-(2-ethylexyl) phosphate (TEHP) | 4300 ngL−1 | |||||||

| 2-Ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate (EHDPP) | 7.7–730 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Tricresyl phosphate (TCP) | 8100 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Tris-(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPPi) | Used as plasticizers and antifoam agents | 25–600 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Tributyl phosphate (TBP) | 29 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Triethyl phosphate (TEP) | 9.6–500 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Phthalate ester plasticizers (PEP) | Dibutyl phthalate (DBP) | Are added to polymers to ease processing and to enhance flexibility and toughness of the final product | Waters, sediments, and soil samples | 350–16,000 ngL−1 | Napoleon gulf, Murchison, Waiya, Entebbe, and Thurston bays, Uganda | 2021 | [43] | |

| Bis-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) | 210–23,000 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Dimethyl phthalate | 6.8–400 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Diethyl phthalate (DEP) | 38–1100 ngL−1 | |||||||

| N-butyl benzenesulfonamide (NBBS) | 7.5–200 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Bis-(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (DEHA) | 12–6100 ngL−1 | |||||||

| Personal Care Products | Antimicrobial | Triclosan | Antibiotics in soaps, toothpaste, detergents | Wastewater Effluents | 89–1400 ngL−1 | Napoleon gulf, Murchison, Waiya, Entebbe, and Thurston bays, Uganda | 2021 | [43] |

| Organic sunscreens | Benzophenone | Protect the products from UV light | 36–1300 ngL−1 | |||||

| 4-methylbenzylidine camphor | Organic UV filters | 21–1500 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Phenolic antioxidants | Butylated hydroxytoluene | Used as an antioxidant in cosmetic product formulations | 14–750 ngL−1 | |||||

| Synthetic musk fragrances | Musk ketone | Used in cleaning and washing agents, surface treatments, lubricants and additives | 7.3–460 ngL−1 | |||||

| Preservatives | Chlorophene | Used to be applied as a preservative and disinfectant in personal care products | 21–310 ngL−1 | |||||

| Masking agent | Acetophenone | Covers the unpleasant scents of other ingredients | 2.2–100 ngL−1 | |||||

| 3-methylindole | It is used as a flavoring ingredient | 1.8–130 ngL−1 | ||||||

| Insect repellents | N, N-diethyltoluamide | Is an active ingredient in many insect-repellent products | 3.9–98 ngL−1 | |||||

| Preservatives | 3-tert-butyl-4-hydroxy anisole | Is used as an antioxidant and preservative | 7.3–100 ngL−1 | |||||

| Antioxidant | 2,6-di-tert-butyl-phenol | They are used as stabilizers, free-radical scavengers, and antioxidants | 66 ngL−1 | |||||

| Heavy metals | Post-transition metals | Pb | Battery assembling, in gasoline | Water, sediments, dairy, and beef product samples | 79–138.18 mg/kg | Nakivubo channelized stream sediments and in Kampala markets, Uganda | 2009–2021 | [32,34,47,48,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] |

| Transition metals | Cd | Find applications in batteries, alloys, coatings (electroplating), solar cells, plastic stabilizers, and pigments | Water, sediments, Roadside soils, surface films, and selected vegetable weeds | 0.84–1.04 mg/kg | ||||

| Transition metals | Cu | Find applications in electrical wiring, roofing, plumbing, and industrial machinery. | Sludge waste, dairy and beef products, soil, food crops, groundwater, Industrial effluents, Herbal medicine, rainwater, sediments, food items, water sediments, dumpsites | 28.84–38.01 mg/kg | Nakivubo stream, Southwestern Uganda, Kilembe copper mines, Jinja steel rollings and Osukuru phosphate mines, Kampala markets, L. Victoria | 2006–2021 | [32,33,36,47,86,87,88,89,90,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102] | |

| Trace element | Zn | Smelting and galvanization | Roadside soils, surface films, and selected vegetable weeds | 177.89–442.40 mg/kg | Kampala city roads, Uganda | 2017–2022 | [47,83,89,101,102] | |

| Transition metals | Mn | Welding, making structural alloys | Food crops, | 363.47 mg/kg | Kampala City, Uganda | 2004–2019 | [33,48,52,71] | |

| Transition metal | Fe | Making alloy steels | Groundwater, soils, stream sediments, and food crops. | 30,085.33–5835.00 mg/kg | Nakivubo stream, Kilembe copper mines, southwestern Uganda areas | 2004–2021 | [33,91,92,95,99,103] | |

| Transition metal | Ni | Use in alloying such as in armor plating | Soils, surface water, herbal medicines, and food items | 2.2–9.40 ppm | Jinja steel rolling mills, areas of southwestern Uganda, and Kampala markets | 2015–2020 | [87,98,99] | |

| Metalloid | As | Used as an allowing agent as well as in making glass, pigments, textiles, and both metal and wood adhesives | Up and Downstream waters, soil, surface water, and plant tissues | 0.5–4.6 ppm | Roofings rolling mills, steel and tube industries in Nakawa Industrial area and areas of Kilembe copper mines, Uganda | 2007–2022 | [47,87,91,92] | |

| Transition metals | Co | Making alloys, find applications in magnets and is also used as a catalyst in petroleum industries. | Surface water, vegetables, and medicinal herbal samples | 0.233 g/mL | River Nyamwamba areas in Kasese, southwestern Uganda parts, and Soroti district | 2010–2020 | [33,86,98] | |

| Transition metals | Hg | Find applications in gold extraction and also used in manometers | Soils, Food samples, Surface waters | 0.05 ± 0.01 ppm | Kampala, Wakiso and Busia districts, Uganda | 2009–2022 | [34,47,103] | |

| Transition metals | Cr | Applied in the manufacture of steel as well as hardening steel | Soils, Dairy products, Herbal samples, Food samples | 156.9 ppm | Steel and Tube industrial area, Roofings rolling mills area, Kampala and Soroti districts, Uganda | 2010–2022 | [32,104] | |

| Transition metal | Fe | Making alloy steels | Sediments, Soils, Surface Waters, | 64.05–147.40 mg/Kg | Industrial effluents in Kampala and Soroti districts, Nakivubo stream, and Osukuru phosphate mines areas, Uganda | 2007–2022 | [87,91,92] | |

| Hydrocarbon Compounds | High and Low molecular Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Acenaphthene | Used to prepare naphthalene dicarboxylic anhydride, which is a precursor to dyes | Leachates and Groundwater samples | 1020 ng/L | Bwaise and Wobulenzi towns in Kampala district, Uganda | 2013–2021 | [67,69,105] |

| Acenaphthylene | Used to make electrically conductive polymers | 92 ng/L | ||||||

| Anthracene | Used in the manufacture of red dye alizarin, wood preservation, insecticide, coating of material | 340 ng/L | ||||||

| Benzo[a]pyrene | No known uses | 405 ng/L 1.1 ng/L | ||||||

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | Majorly used for research purposes | 180 ng/L 226 ng/L | ||||||

| Chrysene | Used to make some dyes. | 102 ng/L 224 ng/L | ||||||

| Fluoranthene | No found uses but is produced by some plants. | 550 ng/L 580 ng/L | ||||||

| Fluorene | Used to make dyes, plastics, and pesticides. | 480 ng/L 240 ng/L | ||||||

| Naphthalene | Industrial solvent | 570 ng/L 258 ng/L | ||||||

| Phenanthrene | Used to make dyes, plastics and pesticides, explosives and drugs | 220 ng/L 1050 ng/L | ||||||

| Pyrene | Used to produce dyes, plastics, and pesticides. | 40–687 ng/L | ||||||

| BTEX compounds | Benzene | Industrial solvent | 86.7 ng/L | |||||

| Ethylbenzene | Industrial solvent | 5–960 ng/L | ||||||

| Xylene | Industrial solvent | 410 ng/L | ||||||

| Low and High Molecular Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Naphthalene | Naphthalene | Sediments and Fish tissues | 184–239 ng g−1 d.w. | The White Nile environment near melt oil fields, South Sudan, Uganda Napoleon Gulf, and Murchison Bays | 2017–2021 | [67,105,106] | |

| Acenaphthylene | Used to make electrically conductive polymers | 16–20.5 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Fluorene | Used to make dyes, plastics, and pesticides. | 148–156 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Anthracene | Used in the artificial manufacture of red dye alizarin, wood preservation, insecticide, coating of material | 79.3–112 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Fluoranthene | No found uses and is said to be produced by some plants. | 2.46–8.73 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Pyrene | Used to produce dyes, plastics, and pesticides. | 2.09–5.7 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Benzo[a]anthracene | Can be found in coal tar, roasted coffee, smoked foods, and automobile exhaust and is used in research laboratories | 0.5–1.3 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Chrysene | Used to make some dyes. | 8.4–25 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | Research purpose | 2.7–9.3 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | Research purpose | 0.6–6.5 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Benzo[a]pyrene | No known use | 0.02–1.06 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Dibenzo [a, h] anthracene | Is used only for research purposes to induce tumorigenesis | 1.0–1.9 ng g−1 d.w. | ||||||

| Chlorinated aromatic chemicals | Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs) | Applicable in chemicals, notably herbicides | Sediments | 44.1 pg g−1 dry weight (d.w.) | Napoleon Gulf and Thurston Bay on the northern shore of L. Victoria, Uganda | |||

| Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs) | 5.61 pg g−1 dry weight (d.w.) | |||||||

| Dioxin-like Polychlorinated biphenyls (di-PCBs) | 136 pg g−1 d. w. | |||||||

| Biotoxins–Mycotoxins | Aflatoxins | Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) | Exert inhibitory effects on biological processes including DNA synthesis, DNA-dependent RNA synthesis, DNA repair, and protein synthesis | Food Samples | 16.0 ± 3.6 µg/kg | Kitgum district | 2006–2010 | [107,108,109,110] |

| 1.9 ± 0.9 µg/kg | Kitgum and Lamwo districts, Uganda | 2021–2022 | [101,110,111,112,113] | |||||

| 2.9 ± 1.2 µg/kg | ||||||||

| 4.3 ±1.5 µg/kg | ||||||||

| 2.4 ± 1.1 µg/kg | ||||||||

| 3.5 ± 2.9 µg/kg | ||||||||

| 16.0 ± 3.6 µg/kg | ||||||||

| Fish Tissues | 148 ± 46.9 µg/kg | Lake Victoria Basin, Uganda | ||||||

| Fish Tissues | 110 ± 39.9 μg/kg | Lake Victoria Basin, Uganda | 2006–2016 | [107,108] | ||||

| Aflatoxin B2 (AFB2) | Food Samples | 0–540 μg/kg | Mubende, Uganda | 2006–2016 | [107,108] | |||

| 10.5 ± 6.15 μg/kg | Iganga markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 7.3 ± 4.98 μg/kg | Mayuge markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 11.5 ± 0.43 μg/kg | Southwestern Uganda markets | 2010–2021 | [110,114] | |||||

| Food Samples | 15.2 ± 0.20 μg/kg | Southwestern Uganda markets | 2016–2018 | [86,108] | ||||

| 14.0 ± 1.22 μg/kg | Southwestern Uganda markets | 2010 | [110] | |||||

| Aflatoxin G1 [AFG1] | 16.0 ± 1.66 μg/kg | Southwestern Uganda | 2010–2016 | [108,110] | ||||

| 18.6 ± 2.40 (μg/kg) | Southwestern Uganda | [110] | ||||||

| 0–540 μg/kg | Kampala markets, Uganda | [101,107] | ||||||

| 9.6 ± 4.20 μg/kg | Mubende markets, Uganda | [110,114] | ||||||

| 10.1 ± 3.10 μg/kg | Ibanda markets, Uganda | 2010–2020 | [108,113,115] | |||||

| 9.1 ± 4.35 μg/kg | Jinja markets, Uganda | 2010–2020 | ||||||

| 11.0 ± 3.01 μg/kg | Hoima markets, Uganda | |||||||

| Aflatoxin G2 (AFG2) | 10.6 ± 1.63 μg/kg | Mayuge markets, Uganda | ||||||

| 6.5 ± 0.60 μg/kg | Buikwe markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 3.8 ± 1.30 μg/kg | Mpigi markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 7.2 ± 1.99 μg/kg | Masindi markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 8.5 ± 2.56 μg/kg | Bugiri markets, Uganda | 2021 | [114] | |||||

| Aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) | Aflatoxin M1 is usually present in the fermentation broth of Aspergillus parasiticus and is a metabolite of aflatoxin B1 in humans and animals | Food Samples | 60.3 ± 27.99 μg/kg | Kalerwe markets, Uganda | 2010–2017 | [101,110] | ||

| 40.5 ± 12.82 μg/kg | Bukoto markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 10.3 ± 3.54 μg/kg | Nakawa markets, Uganda | 2010–2017 | [101,115] | |||||

| 143.1 μg/kg | Owino markets, Uganda | 2017 | [101] | |||||

| 5.8 ± 12.3 μg/kg | Bugiri markets, Uganda | 2010 | [115] | |||||

| Food Samples | 2.9 ± 6 μg/kg | Bulambuli markets, Uganda | 2010 | [115] | ||||

| 0.7 ± 0.3 μg/kg | Bundibugyo areas, Uganda | |||||||

| 1.0 ± 0.9 μg/kg | Gulu markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 290.7 μg/kg | Hoima areas, Uganda | |||||||

| 2.4 ± 4.0 μg/kg | Iganga markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 145.5 μg/kg | Kabale markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 1.0 ± 0.7 μg/kg | Kapchorwa areas, Uganda | |||||||

| 1.7 ± 0.5 μg/kg | Kasese markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 1.7 ± 0.5 μg/kg | Kiryadongo areas, Uganda | |||||||

| Food Samples | 6.87 μg/kg | Northern Uganda | 2010–2020 | [108,112,113,115] | ||||

| 6.77 μg/kg | Northern Uganda | |||||||

| 1.46 μg/kg | Northern Uganda | |||||||

| 10.24 μg/kg | Northern Uganda | |||||||

| Ochratoxins (OTA) | OTA-A, B, and C | Can benefit humans by their use as antibiotics (penicillins), immunosuppressants (cyclosporine), and in control of postpartum hemorrhage and migraine headaches | Food Samples | 4.4 ± 0.8 n | Kitgum markets, Uganda | 2019–2021 | [112,113,115,116] | |

| 3.5 ± 0.7 ng/g | Lamwo Markets, Uganda | 2010–2020 | ||||||

| 3760 ng/g | Kitgum markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 0.3 ± 0.1ng/g | Lamwo Markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 1.1 ± 0.3 ng/g | Kitgum markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 1.0 ± 0.3 ng/g | Lamwo Markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 1.5 ± 0.3 ng/g | Kitgum markets, Uganda | |||||||

| 1.4 ± 0.2 ng/g | Lamwo market, Uganda s | |||||||

| 4.89 ng/g | Northern Uganda | |||||||

| 0.37 ng/g | Northern Uganda | |||||||

| 1.32 ng/g | Northern Uganda | |||||||

| 7.44 ng/g | Northern Uganda | |||||||

| Fumonisins | A, B, C, and P-series | Are usually esterified with propane tricarboxylic acid to provide a hydrophobic/hydrophilic dichotomy that is unique among the mycotoxins | Fish Tissues | 0.3 ± 0.19 μg/kg | Lake Victoria Basin, Uganda | 2011–2021 | [113,117,118,119] | |

| 0.2 ± 0.24 μg/kg | Lake Victoria Basin, Uganda | 2021 | [113] | |||||

| Food Samples | 80.2–0.6 μg/kg | Kampala markets | 2016 | [108] | ||||

| 1.19 μg/kg | Northern parts of Uganda’s markets | 2000–2021 | [113,115,120] | |||||

| 19.4–99.8 μg/kg | 2011–2021 | [113,117,118,119] | ||||||

| 0.76 μg/kg | ||||||||

| 4.402 μg/kg | ||||||||

| Trichothecene | Vomitoxin/Deoxynivalenol | Is used as a mycotoxin to induce cytotoxicity in porcine jejunal epithelial cells and study the protective effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the cell viability of host cells. | Food Samples | 0.153 μg/kg | Northern parts of Uganda’s markets | 2011–2021 | [113,117,118,119] | |

| 0.92793 μg/kg | ||||||||

| 0.153 μg/kg | ||||||||

| 0.823 μg/kg | ||||||||

| Radionuclides and electromagnetic radiation | Primordial radionuclides (naturally occurring noble gases) | Radon (226Ra) | Uranium-238. Used in making nuclear weapons as a ‘tamper’ material. | Plant Tissues and Food samples | 8.06 Bq/kg | Osukuru phosphate factory areas, Tororo District, Uganda | 2020–2021 | [121,122] |

| 7.08 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 3.55 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 9.14 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 5.34 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 4.35 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 10.02 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 4.88 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 2.99 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| Tororo cement factory area | 18 ± 3 Bqm−3 | Dormitories at Adwari S.S., Uganda | 2014–2020 | [98,121,122,123] | ||||

| 31 ± 3 Bqm−3 | Dormitories at Ogor Seed S.S., Uganda | |||||||

| 26 ± 3 Bqm−3 | Dormitories at Okwang S.S., Uganda | |||||||

| 26 ± 2 Bqm−3 | School Dormitories at Orum S. S, Uganda | |||||||

| 49 ± 5 Bqm−3 | Dormitories at Otuke S.S., Uganda | |||||||

| Tororo mining area | 97 ± 5 Bqm−3 | Tororo district | ||||||

| Chemical Laboratory tests | 96 ± 4 Bqm−3 | Eastern Uganda | 2014–2022 | [95,121,122,123] | ||||

| Steel company area | 72 ± 3 Bqm−3 | Steel Works in Eastern Uganda | ||||||

| Hospital area | 51 ± 2 Bqm−3 | Hospitals in Eastern Uganda | ||||||

| Hotel | 28 ± 1 Bqm−3 | TLT Hotel in Eastern Uganda | ||||||

| Residential houses | 92 ± 4 Bqm−3 | Residential houses (closed) in Eastern Uganda | ||||||

| Homesteads | 45 ± 1 Bqm−3 | Houses (Far away) in Eastern Uganda | ||||||

| Thorium (232Th) | Used in making lenses for cameras, scientific instruments, high-temperature crucibles, and electrical equipment | Soil mine tailings | 119.3–376.7 Bq kg−1 | Mashonga Gold Mine, Uganda | 2016 | [124] | ||

| 211.7 ± 17.3 Bq kg−1 | Kikagati Tin mine, Uganda | |||||||

| 244.4 ± 10.9 Bq kg−1 | Butare Iron ore mine, Uganda | |||||||

| Food Samples | 18.60 Bq/kg | Medicinal plants in Osukuru, Tororo District, Uganda | ||||||

| 15.51 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 7.67 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 11.26 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 11.57 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 5.98 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 13.28 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 7.37 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 3.00 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 2.24 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| Air | 181.2 ± 66.8 nGy h−1 | Mashonga Gold Mine, Uganda | 2016 | [124] | ||||

| 167.2 ± 43.0 nGy h−1 | Kikagati Tin mine, Uganda | |||||||

| 191.6 ± 29.6 nGy h−1 | Butare Iron ore mine, Uganda | |||||||

| 40K (Potassium-40) | Acts as a signaling molecule in a wide variety of processes | Food Samples | 350.17 Bq kg−1 | Osukuru mines, Tororo District, Uganda | 2021 | [121] | ||

| 141.0–1658.5 Bq kg−1 | ||||||||

| 365.35 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 297.81 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 437.92 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 419.72 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 343.78 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 379.21 Bq/kg | ||||||||

| 363.99 Bq/kg | ||||||||