Gender and Age, but Not Visual Context, Impact Wildlife Attitudes and Perceptions of Animals in Zoos

Abstract

:1. Introduction

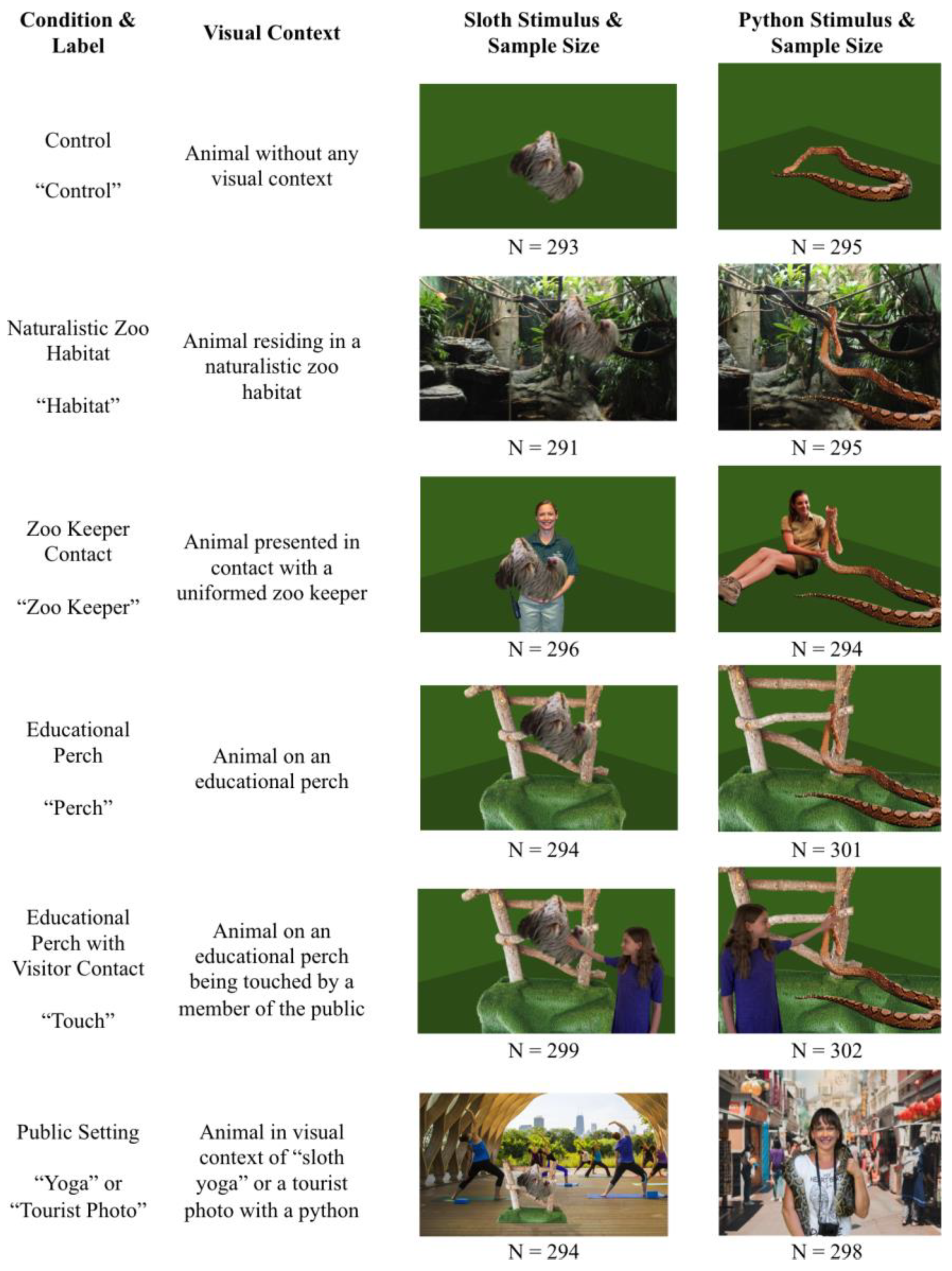

2. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Principal Components Analyses

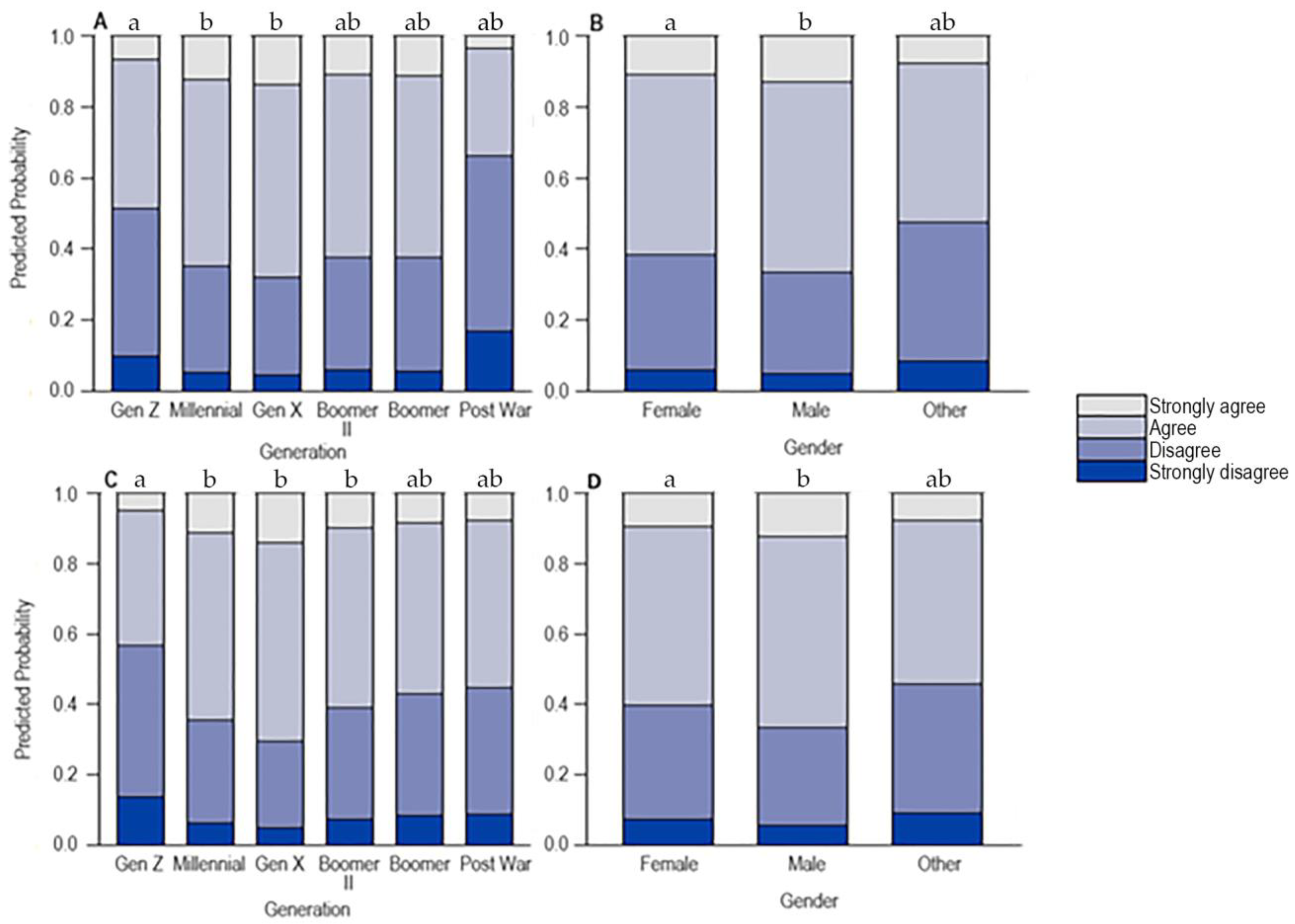

3.2. Predicting Attitudes

3.3. Predicting Perceptions of Animals in Zoos

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fulton, D.C.; Manfredo, M.J.; Lipscomb, J. Wildlife value orientations: A conceptual and measurement approach. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 1996, 1, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajal, A.; Luebke, J.F.; DeGregoria Kelly, L.; Matiasek, J.; Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T.; Saunders, C.D.; Goldman, S.R.; Mann, M.E.; Stanoss, R. The complex relationship between personal sense of connection to animals and self-reported proenvironmental behaviors by zoo visitors. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellert, S. From Kinship to Mastery: A Study of American Attitudes toward Animals; Report to the Fish and Wildlife Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Public Attitudes toward Critical Wildlife and Natural Habitat Issues, Phase I; Report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Zoological Parks in American Society. In Proceedings of the American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 30 September–4 October 1979; pp. 88–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Activities of the American Public Relating to Animals, Phase II; Report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. American attitudes toward and knowledge of animals: An update. In Advances in Animal Welfare Science 1984/85; Fox, M.W., Mickley, L.D., Eds.; The Humane Society of the United States: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; pp. 177–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Attitudes, knowledge, and behavior toward wildlife among the industrial superpowers: United States, Japan, and Germany. J. Soc. Issues 1993, 49, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Values and perceptions of invertebrates. Conserv. Biol. 1993, 7, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Berry, J.K. Attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors toward wildlife as affected by gender. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1987, 15, 363–371. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Dunlap, J. Informal Learning at the Zoo: A Study of Attitude and Knowledge Impacts; Unpublished Report to the Zoological Society of Philadelphia; Zoological Society of Philadelphia: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas, K.; Ross, S. Zoo visitor knowledge and attitudes toward gorillas and chimpanzees. J. Environ. Educ. 2005, 36, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau, L. Development and Validation of the Biophilic Attitudes Inventory (BAI). Doctoral Dissertation, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J.A. Factors influencing human attitudes to animals and their welfare. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, B.; Devers, P.; Krausman, P. The relationship of gender to species conservation attitudes. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2001, 29, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner, W.A.; Ritchie, V.P.; Stauffer, D.F. Opinions on wildlife: Responses of resource managers and wildlife users in the Southeastern United States. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1989, 17, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gamborg, C.; Jensen, F.S. Wildlife value orientations: A quantitative study of the general public in Denmark. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2016, 21, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.; Vrij, A.; Cherryman, J.; Nunkoosing, K. Attitudes towards animal use and belief in animal mind. Anthrozoös 2004, 17, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, V.; Tribe, A.; Toukhsati, S.; Phillips, C.J.C. Public attitudes in India and Australia toward elephants in zoos. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reade, L.S.; Waran, N.K. The modern zoo: How do people perceive zoo animals? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 47, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrikson, M.; Annas, P.; Fischer, H.; Wik, G. Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias. Behav. Res. Ther. 1996, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Wang, X.; Ye, H.; Wang, H.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Feng, J. Does public fear that bats spread COVID-19 jeopardize bat conservation? Biol. Conserv. 2021, 254, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, J.W. Attitudes toward animal use. Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Martens, P. Public attitudes toward animals and the influential factors in contemporary China. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.T.; Vernon, R. Tracking Data Analysis (Report to the Public Relations Committee). In Proceedings of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums Meeting Weeks, Virtual, 15 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, K.A.; Leahy, M.; Ross, S.R.; Schook, M.W.; Ferrie, G.M.; Alba, A.C. Younger generations are more interested than older generations in having non-domesticated animals as pets. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, O.E., Jr.; Saunders, C.D.; Birjulin, A.A. Emotional dimensions of watching zoo animals: An experience sampling study building on insights from psychology. Curator 2004, 47, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, M.J. Warming a Cold Shoulder: Animal Ethics, Sentience, and Preferences for Human Interaction in Zoo-housed Non-Avian Reptiles. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, D.L.; Hepper, P.G. Pet ownership and adults’ views on the use of animals. Soc. Anim. 1997, 5, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K.; Dierking, L. Conservation learning in wildlife tourism settings: Lessons from research in zoos and aquariums. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Reinhard, E.M.; Vernon, C.L.; Bronnenkant, K.; Heimlich, J.E.; Deans, N.L. Why Zoos and Aquariums Matter: Assessing the Impact of a Visit to a Zoo or Aquarium; Association of Zoos and Aquariums: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Reading, R.P.; Miller, B.J.M. Attitudes and attitude change among zoo visitors. In Zoos in the 21st Century: Catalysts for Conservation? Zimmermann, A., Hatchwell, M., Dickie, L., West, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2007; pp. 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, U.S.; Kelling, A.S.; Pressley-Keough, R.; Bloomsmith, M.A.; Maple, T.L. Enhancing the zoo visitor’s experience by public animal training and oral interpretation at an otter exhibit. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 826–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Zoos and Aquariums Ambassador Animal Policy. Available online: https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2332/ambassador_animal_policy_2015.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- D’Cruze, N.; Khan, S.; Carder, G.; Megson, D.; Coulthard, E.; Norrey, J.; Groves, G. A global review of animal-visitor interactions in modern zoos and aquariums and their implications for wild animal welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horak, J.C. Wildlife documentaries: From classical forms to reality TV. Film Hist. 2006, 18, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.E.; Hunt, K.A.; Riley, L.M. Animals in an online world; an evaluation of how zoological collections use social media: Social media in zoos. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2018, 6, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fukano, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Soga, M. Zoos and animated animals increase public interest in and support for threatened animals. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinez, A.M.; Fernandez, E.J. What is the zoo experience? How zoos impact a visitor’s behaviors, perceptions, and conservation efforts. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, M.J. Human-animal interactions in zoos: What can compassionate conservation, conservation welfare and duty of care tell us about the ethics of interacting, and avoiding unintended consequences? Animals 2020, 10, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, S.L.; Stride, J.R. Animal-human two-shot images: Their out-of-context interpretation and the implications for zoo and conservation settings. Zoo Biol. 2021, 40, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.N.; McLeod, E.M.; Borrie, W.T.; Miller, K.K. Human positioning in close-encounter photographs and the effect on public perceptions of zoo animals. Animals 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighty, K.A.; Valuska, A.J.; Grand, A.P.; Bettinger, T.L.; Mellen, J.D.; Ross, S.R.; Boyle, P.; Ogden, J.J. Impact of visual context on public perceptions of non-human primate performers. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroepfer, K.K.; Rosati, A.G.; Chartrand, T.; Hare, B. Use of “entertainment” chimpanzees in commercials distorts public perception regarding their conservation status. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.R.; Vreeman, V.M.; Lonsdorf, E.V. Specific image characteristics influence attitudes about chimpanzee conservation and use as pets. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Ali, Z.; Nemat, A.; Sikander, S.K.; Hussain, Z.; Saleem, K. The study of public perception for captive animals at Lahore Zoo, Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2015, 25, 509–513. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, S.; Bard, K.; Vrij, A.; Brandon, D. Human rights, animal wrongs? Exploring attitudes toward animal use and possibilities for change. Soc. Anim. 2010, 18, 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, S.; Herzog, H.A. Personality and attitudes toward the treatment of animals. Soc. Anim. 1997, 5, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Povey, K.D.; Rios, J. Using interpretive animals to deliver affective messages in zoos. J. Interpret. Res. 2002, 7, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stazaker, K.; Mackinnon, J. Visitor perceptions of captive, endangered barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) used as photo props in Jemaa El Fna Square, Marrakech, Morocco. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle, W. Psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. R Package Version 2.1.6. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 5th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H. An index of factor simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.J. Companion Package to the Book “R: Einführung Durch Angewandte Statistik”_. R Package Version 0.9.3. 2015. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=REdaS (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Cattell, R.B. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimock, M. Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Res. Cent. 2019, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, A.; Sendén, M.G.; Renström, E.A. What is gender, anyway: A review of the options for operationalising gender. Psychol Sex 2020, 18, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/ (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Lenth, R.V. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R Package Version 1.6.3. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Available online: https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4/ (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Schlegel, B.; Steenbergen, M. Brant: Test for Parallel Regression Assumption. R Package Version 0.3-0. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=brant (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Brant, R. Assessing proportionality in the proportional odds model for ordinal logistic regression. Biometrics 1990, 46, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Teel, T.L.; Henry, K.L. Linking society and environment: A multilevel model of shifting wildlife value orientations in the Western United States. Soc. Sci. Q. 2009, 90, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teel, T.L.; Manfredo, M.J. Understanding the diversity of public interests in wildlife conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 24, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaske, J.J.; Jacobs, M.H.; Sijtsma, M.T. Wildlife value orientations and demographics in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2011, 57, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liordos, V.; Kontsiotis, V.J.; Eleftheriadou, I.; Telidis, S.; Triantafyllidis, A. Wildlife value orientations and demographics in Greece. Earth 2021, 2, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, H.C.; Manfredo, M.J.; Barro, S.C. Patterns of wildlife value orientations in hunters’ families. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2002, 7, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruska, J.; Maresova, P. Use of social media platforms among adults in the United States—Behavior on social media. Societies 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, C.; Cheyne, S.; Waters, S.; Svensson, M. Professional primate keepers and online primate imagery: An assessment of knowledge and attitudes. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2021, 9, 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, A. Social media usage. Pew Res. Cent. 2015, 125, 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries, V. Unlocking the power of the ‘like’ button—Leveraging the science of social media to support WAZA members. WAZA NEWS Mag. 2020, 4, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi, C.; Speiran, S.; Grasso, C. “Let me take a selfie”: Implications of social media for public perceptions of wild animals. Soc. Anim. 2020, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, S.; Setchell, J.M.; Maréchal, L.; Oram, F.; Wallis, J.; Cheyne, S.M. Best Practice Guidelines for Responsible Images of Non-Human Primates. A Publication of The IUCN Primate Specialist Group Section for Human-Primate Interactions. Available online: http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/id/eprint/43949/1/HPI-Imagery-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Carder, G.; Plese, T.; Machado, F.C.; Paterson, S.; Matthews, N.; McAnea, L.; D’Cruze, N. The impact of ‘selfie’ tourism on the behaviour and welfare of brown-throated three-toed sloths. Animals 2018, 8, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnen, V.; Kanaan, V. Wildlife trade in Brazil: A closer look at wild pets welfare issues. Braz. J. Biol. 2014, 74, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppli, C.A.; Fraser, D.; Bacon, H.J. Welfare of non-traditional pets. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2014, 33, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Essen, E.; Lindsjš, J.; Berg, C. Instagranimal: Animal welfare and animal ethics challenges of animal-based tourism. Animals 2020, 10, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietz, P. Research into questionnaire design: A summary of the literature. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 52, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrico, J.F. The survival of animal care organizations impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. EELJ 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Berinsky, A.J.; Huber, G.A.; Lenz, G.S. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Polit. Anal. 2012, 20, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Fraser, J.; Saunders, C. Zoo experiences: Conversations, connections, and concern for animals. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Survey Statement | Attitude |

|---|---|

| 2. People should have the right to buy and keep a sloth (python) if they want to. [44] | Dominionistic |

| 3. Allowing people to hold or handle a sloth (python) for a photo opportunity should be banned. [50] | Dominionistic |

| 4. I would enjoy learning about the ecosystem of wild sloths (pythons). [12] | Ecoscientistic |

| 5. I am very interested in learning about wild sloth (python) populations in nature. [12] | Ecoscientistic |

| 6. It is important that we learn as much as we can about wildlife. [1] | Ecoscientistic |

| 7. I am afraid of sloths (pythons). [12] | Negativistic |

| 8. I think sloths (pythons) are unclean and full of disease. [12] | Negativistic |

| 9. I do not think sloths (pythons) are smart enough to be trained in a zoo. [12] | Negativistic |

| 10. I like to see pictures or watch TV programs depicting animals like sloths (pythons), but I have little desire to see them in the wild. [12] | Naturalistic |

| 11. I would be thrilled to take a tour in Central/South America (Asia) to see sloths (pythons) in the wild. [12] | Naturalistic |

| 12. If I were to take a tour in Central/South America (Asia), I would prefer to stay in a modern facility in a city rather than in nature where there might be wild sloths (pythons) around. [12] | Naturalistic |

| 13. I think love is an emotion that people should feel for other people, not for sloths (pythons). [12] | Utilitarian |

| 14. I think it is okay if wild animals participate in experiences such as sloth yoga (tourist photos). [12] | Utilitarian |

| 15. If there are plenty of sloths (pythons) in the wild, I believe people should be allowed to hunt or capture and sell them if it helps improve their livelihood. [12] | Utilitarian |

| 16. It harms animals to use them in the media, such as commercials, television programs, or movies. [44] | Moralistic |

| 17. In my opinion, animals are definitely inferior to humans. [47] | Moralistic |

| 18. There should be extremely harsh penalties including jail sentences for people who participate activities that result in cruelty to animals. [48] | Moralistic |

| 19. I am, or could become, very emotionally attached to some of the sloths (pythons) I see at the zoo. [12] | Humanistic |

| 20. I feel a sense of connection with the animals I see at a zoo. [2] | Humanistic |

| 21. I do not feel affectionate toward animals I see at a zoo. [7] | Humanistic |

| Survey Statement | Principal Component (Attitude Type) with Eigenvalues | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sloth Experiment | Python Experiment | |||||||

| 1 (Negative) | 2 (Positive) | 3 | 4 | 1 (Positive) | 2 (Negative) | 3 | 4 | |

| 2 | 0.654 | 0.142 | −0.174 | 0.177 | not included in python PCA | |||

| 3 | 0.144 | 0.662 | 0.112 | 0.706 | ||||

| 4 | −0.103 | 0.769 | 0.742 | 0.213 | ||||

| 5 | 0.760 | 0.156 | 0.789 | 0.118 | ||||

| 6 | −0.370 | 0.390 | 0.160 | −0.188 | 0.584 | |||

| 8 | 0.545 | −0.168 | 0.323 | 0.578 | 0.254 | −0.204 | ||

| 9 | 0.578 | −0.117 | 0.286 | 0.492 | 0.168 | |||

| 10 | 0.504 | −0.133 | 0.236 | 0.204 | 0.384 | 0.130 | ||

| 11 | 0.709 | −0.139 | 0.774 | |||||

| 12 | 0.400 | −0.292 | 0.192 | 0.278 | −0.364 | 0.365 | 0.259 | |

| 13 | 0.679 | −0.126 | 0.229 | −0.142 | 0.635 | −0.152 | ||

| 14 | 0.674 | 0.213 | −0.125 | 0.164 | 0.208 | 0.454 | −0.410 | |

| 15 | 0.762 | 0.202 | 0.479 | −0.190 | −0.175 | |||

| 16 | 0.170 | 0.175 | 0.514 | 0.216 | 0.613 | |||

| 17 | 0.607 | −0.133 | 0.621 | −0.125 | −0.215 | |||

| 18 | −0.403 | 0.166 | 0.150 | 0.159 | −0.200 | 0.114 | 0.535 | |

| 19 | 0.621 | 0.104 | 0.294 | 0.700 | 0.170 | |||

| 20 | 0.568 | 0.438 | 0.459 | 0.160 | 0.261 | |||

| 21 | 0.638 | −0.229 | 0.240 | −0.191 | 0.546 | −0.346 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alba, A.C.; Ferrie, G.M.; Schook, M.W.; Leahy, M.; Cronin, K.A. Gender and Age, but Not Visual Context, Impact Wildlife Attitudes and Perceptions of Animals in Zoos. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2023, 4, 118-133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg4010013

Alba AC, Ferrie GM, Schook MW, Leahy M, Cronin KA. Gender and Age, but Not Visual Context, Impact Wildlife Attitudes and Perceptions of Animals in Zoos. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens. 2023; 4(1):118-133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg4010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlba, Andrew C., Gina M. Ferrie, Mandi Wilder Schook, Maureen Leahy, and Katherine A. Cronin. 2023. "Gender and Age, but Not Visual Context, Impact Wildlife Attitudes and Perceptions of Animals in Zoos" Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 4, no. 1: 118-133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg4010013

APA StyleAlba, A. C., Ferrie, G. M., Schook, M. W., Leahy, M., & Cronin, K. A. (2023). Gender and Age, but Not Visual Context, Impact Wildlife Attitudes and Perceptions of Animals in Zoos. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 4(1), 118-133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg4010013