Management Accounting Practices in the Hospitality Industry: A Systematic Review and Critical Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Traditional Management Accounting Practices

1.2. Contemporary Management Accounting Practices

1.3. Other Management Accounting Practices

1.4. Purpose, Research Question, and Objectives

- (1)

- To determine the overall performance in hospitality management accounting.

- (2)

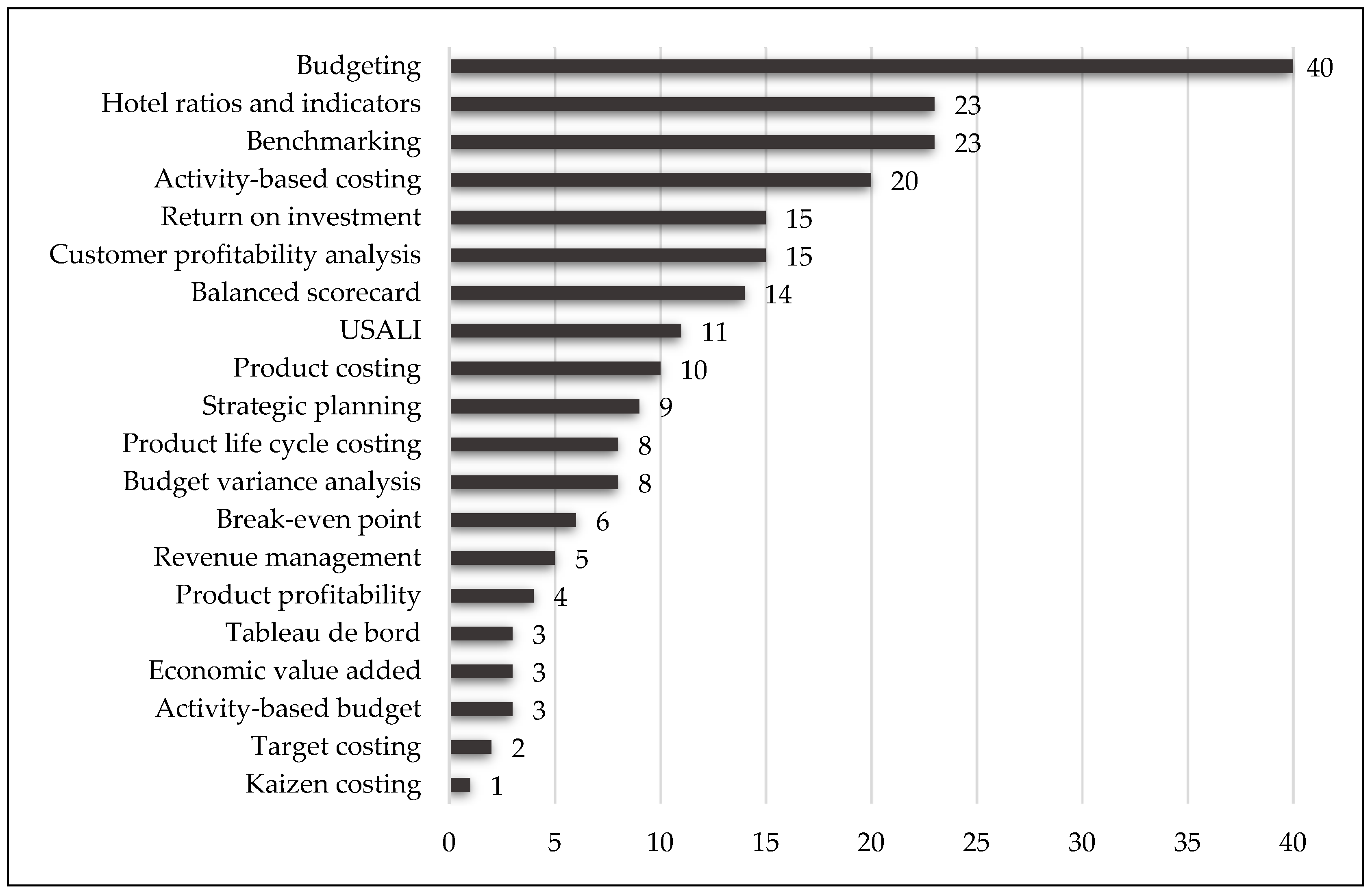

- To determine which management accounting practices are most used in the hospitality industry.

- (3)

- To identify challenges in the implementation of management accounting practices in the hospitality industry.

- (4)

- To identify if there are particular management accounting practices in the hospitality industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Articles Collection

- Management accounting;

- Hospitality industry OR hotel sector;

- Techniques OR practices;

- USALI OR Uniform system of accounts for the lodging industry OR uniform accounting;

- Ratios OR indicators.

- Article title, Abstract, Keywords—management accounting AND (hospitality OR hotel) AND (techniques OR practices OR USALI OR ratios OR indicators OR uniform accounting).

2.2. Analysis Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

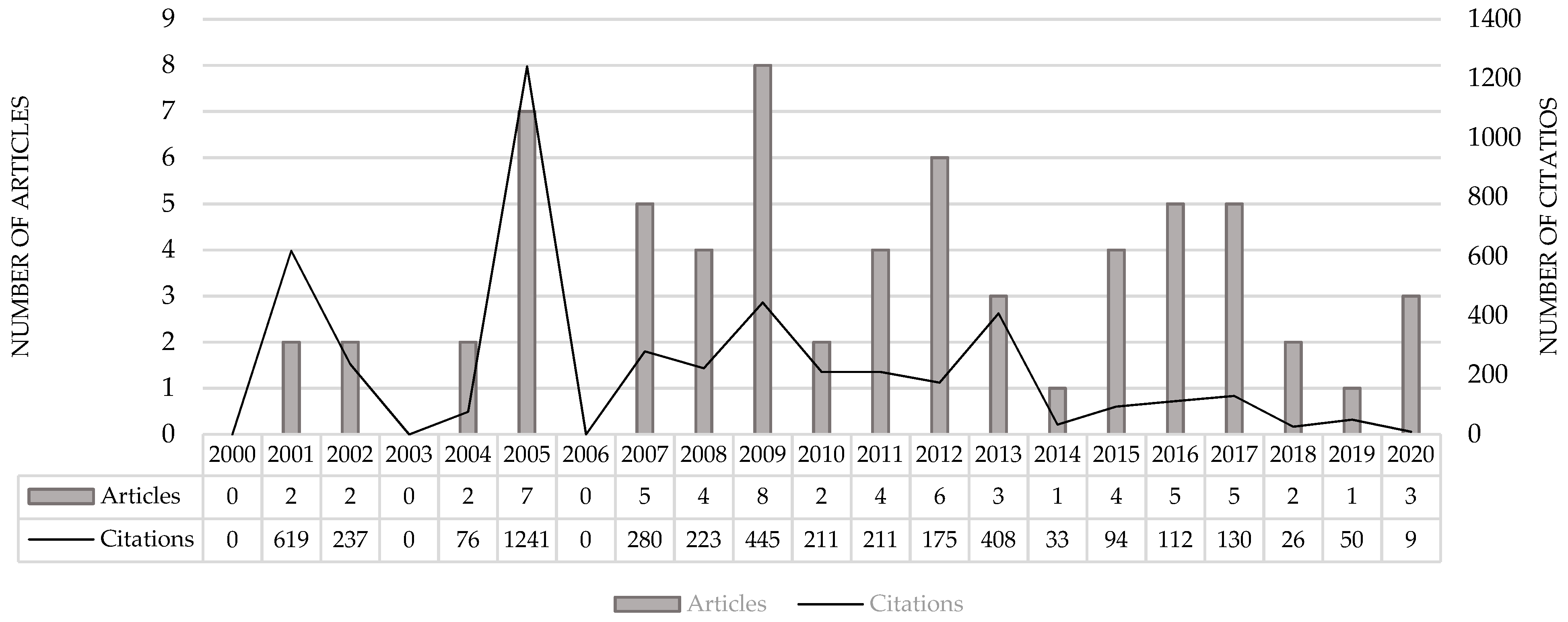

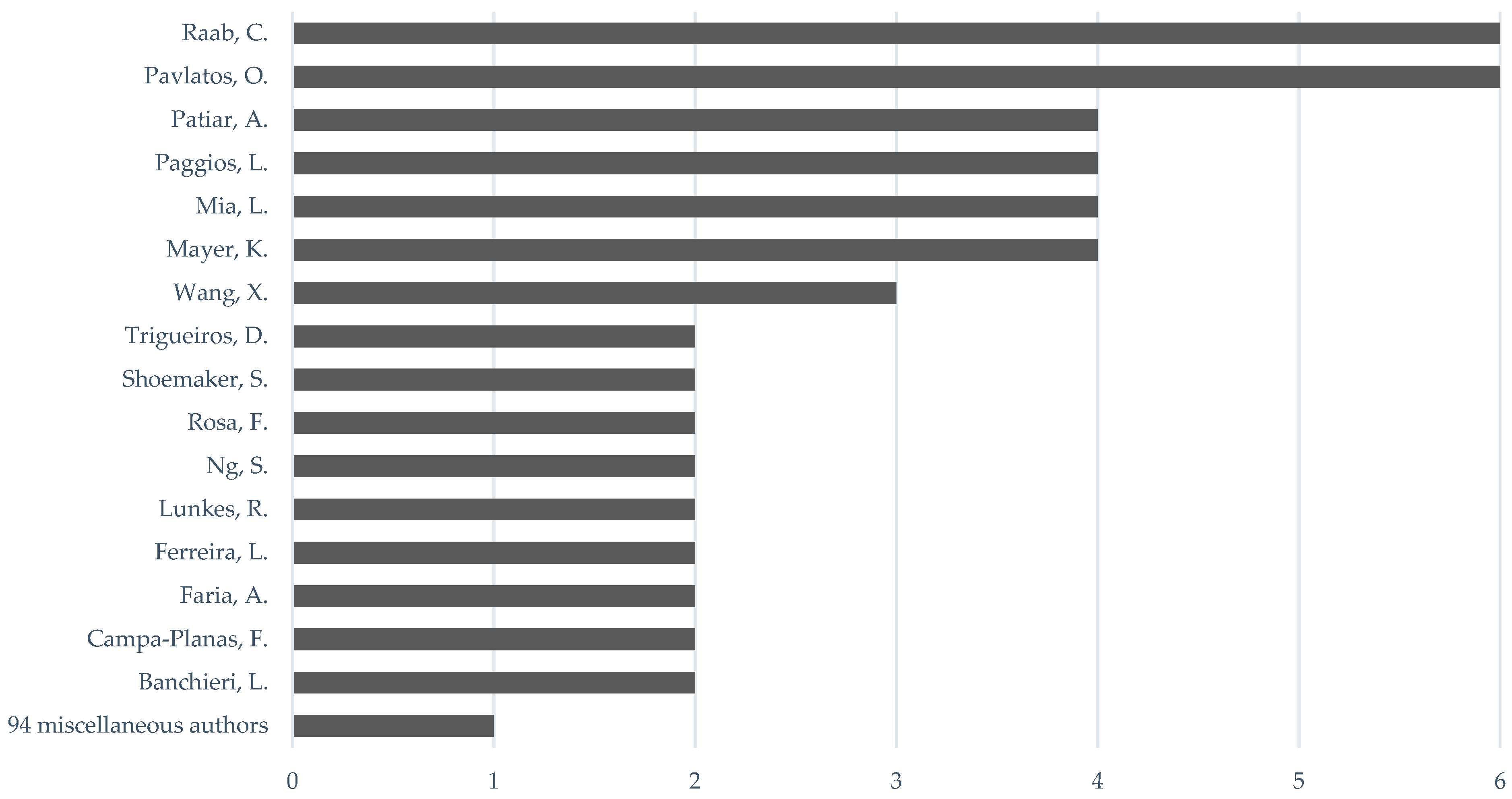

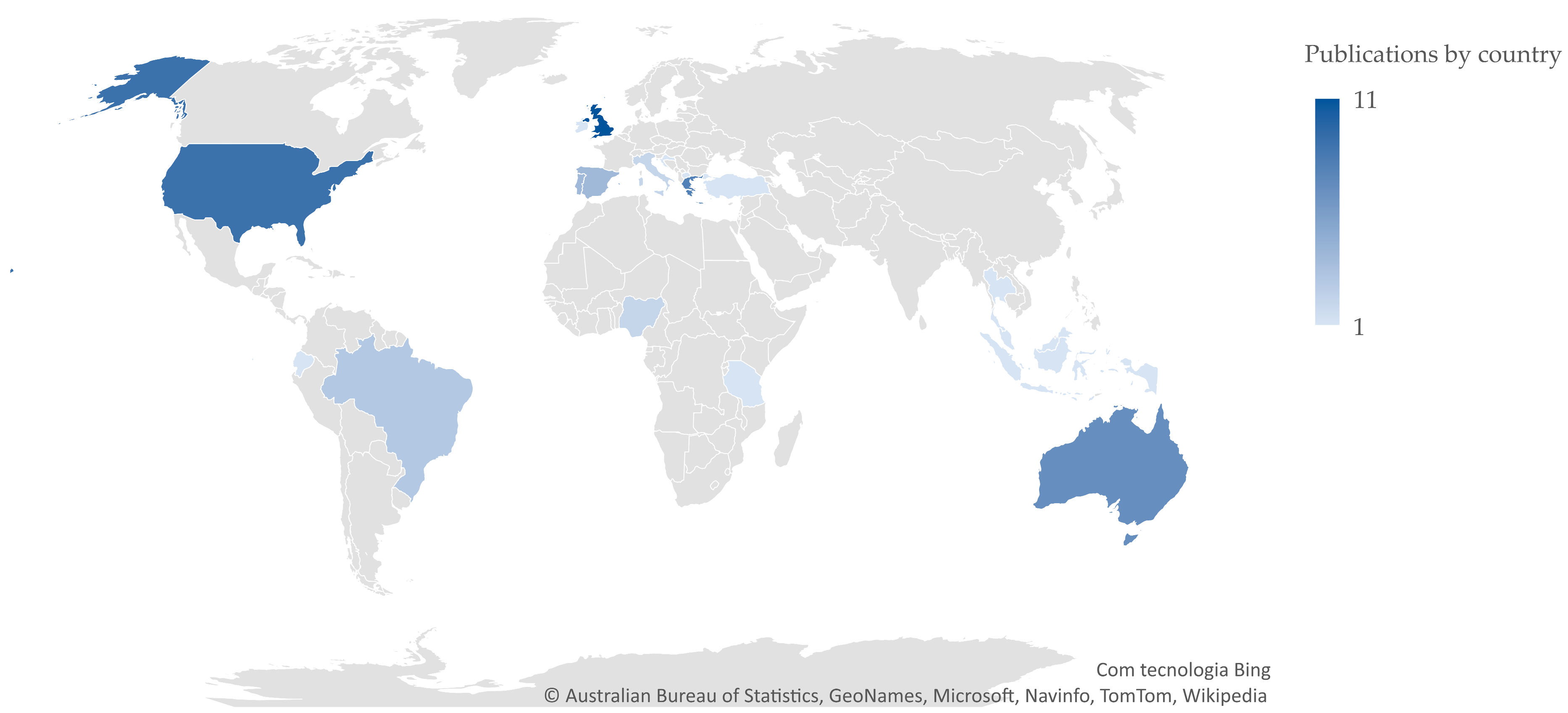

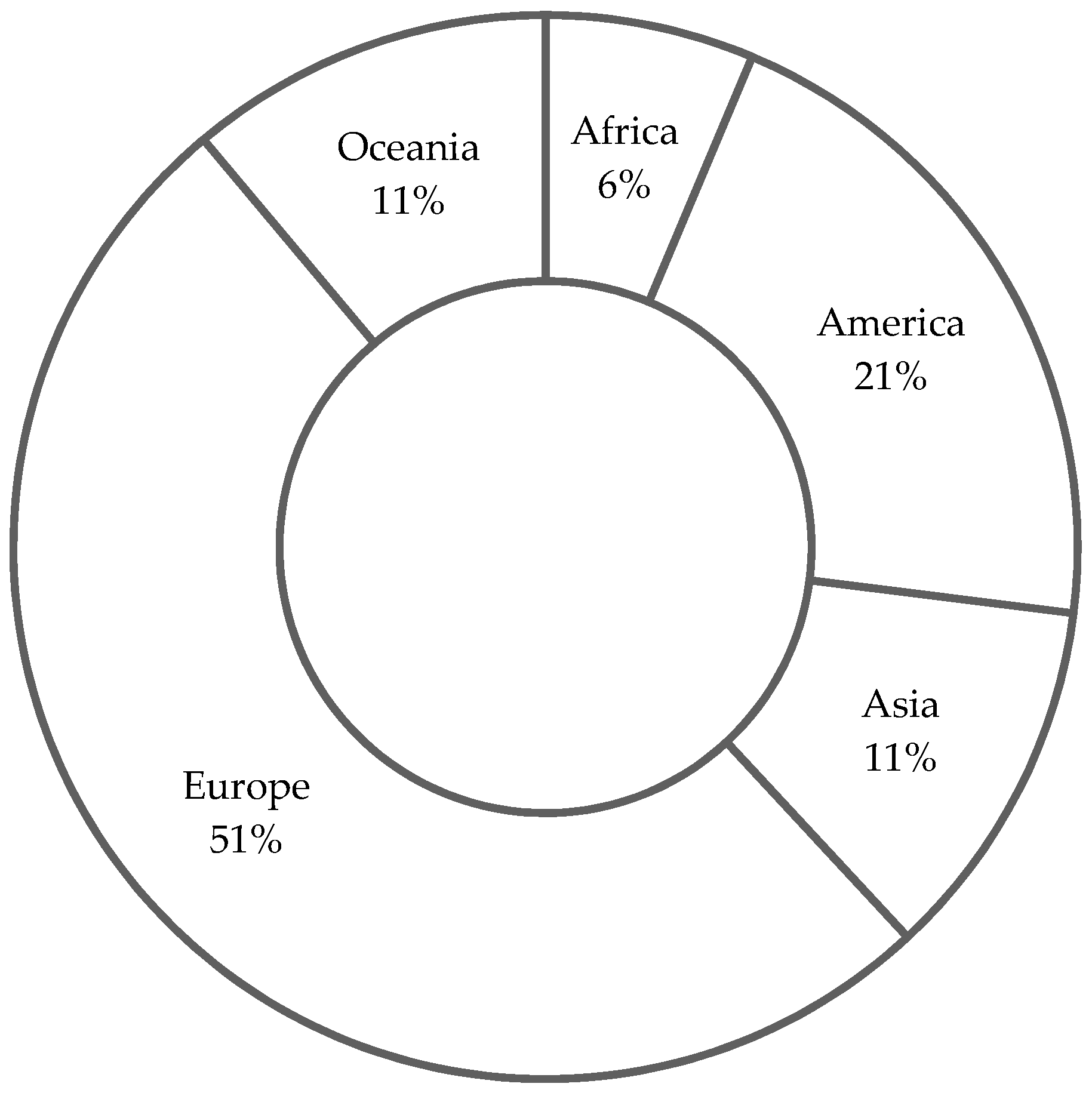

3.1. Overall Performance in Hospitality Management Accounting

3.2. Analysis under a Critical Approach

4. Conclusions

5. Contributions, Implications, Future Research, and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Total of Articles for the Research

| Authors |

| H. Atkinson and J. Brown, “Rethinking performance measures: Assessing progress in UK hotels”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 128–135, 2001, doi:10.1108/09596110110388918. |

| L. Mia and A. Patiar, “The use of management accounting systems in hotels: An exploratory study”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 111–128, 2001, doi:10.1016/s0278-4319(00)00033-5. |

| L. Mia and A. Patiar, “The interactive effect of superior-subordinate relationship and budget participation on managerial performance in the hotel industry: An exploratory study”, J. Hosp. Tour. Res., vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 235–257, 2002, doi:10.1177/1096348002026003003. |

| D. S. Sharma, “The differential effect of environmental dimensionality, size, and structure on budget system characteristics in hotels”, Manag. Account. Res., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 101–130, 2002, doi:10.1006/mare.2002.0183. |

| A. Capiez and A. Kaya, “Yield management and performance in the hotel industry”, J. Travel Tour. Mark., vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 21–31, 2004, doi:10.1300/J073v16n04_05. |

| C. Raab and K. J. Mayer, “Exploring the use of activity-based costing in the restaurant industry”, Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 79–96, 2004, doi:10.1300/J149v04n02_05. |

| R. D. Banker, G. Potter, and D. Srinivasan, “Association of nonfinancial performance measures with the financial performance of a lodging chain”, Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q., vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 394–412, 2005, doi:10.1177/0010880405275597. |

| N. Evans, “Assessing the balanced scorecard as a management tool for hotels”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 376–390, 2005, doi:10.1108/09596110510604805. |

| M. Haktanir and P. Harris, “Performance measurement practice in an independent hotel context: A case study approach”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 39–50, 2005, doi:10.1108/09596110510577662. |

| P. Phillips and P. Louvieris, “Performance measurement systems in tourism, hospitality, and leisure small medium-sized enterprises: A balanced scorecard perspective”, J. Travel Res., vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 201–211, 2005, doi:10.1177/0047287505278992. |

| C. Raab, K. Mayer, C. Ramdeen, and S. Ng, “The application of activity-based costing in a Hong Kong buffet restaurant”, Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 11–26, 2005, doi:10.1300/J149v06n03_02. |

| A. Sharma and A. Upneja, “Factors influencing financial performance of small hotels in Tanzania”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 504–515, 2005, doi:10.1108/0959611051061214 |

| C. Burgess, “Is there a future for hotel financial controllers?”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 161–174, 2007, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2005.10.004. |

| R. B. T. Mattimoe, “An Institutional Explanation and Model of the Factors Influencing Room Rate Pricing Decisions in the Irish Hotel Industry”, Irish J. Manag., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 127–145, 2007. |

| K. Namasivayam, L. Miao, and X. Zhao, “An investigation of the relationships between compensation practices and firm performance in the US hotel industry”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 574–587, 2007, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.05.001. |

| O. Pavlatos and I. Paggios, “Cost accounting in Greek hotel enterprises: An empirical approach”, Tourismos, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 39–59, 2007. |

| . Raab, S. Shoemaker, and K. Mayer, “Activity-based costing: A more accurate way to estimate the costs for a restaurant menu”, Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1–15, 2007, doi:10.1300/J149v08n03. |

| K. Annaraud, C. Raab, and J. R. Schrock, “The application of activity-based costing in a quick service restaurant”, J. Foodserv. Bus. Res., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 23–44, 2008, doi:10.1080/15378020801926627. |

| T. Jones, “Improving hotel budgetary practice-A positive theory model”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 529–540, Dec. 2008, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2007.07.027. |

| D. Lamminmaki, “Accounting and the management of outsourcing: An empirical study in the hotel industry”, Manag. Account. Res., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 163–181, 2008, doi:10.1016/j.mar.2008.02.002. |

| A. Patiar and L. Mia, “The interactive effect of market competition and use of MAS information on performance: Evidence from the upscale hotels”, J. Hosp. Tour. Res., vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 209–234, 2008, doi:10.1177/1096348007313264. |

| A. Adamu and I. A. Olotu, “The practicability of activity—Based costing system in hospitality industry”, J. Financ. Account. Res., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 36–49, 2009, doi:10.2139/ssrn.1397255. |

| M. J. S. Devesa, L. P. Esteban, and A. G. Martínez, “The financial structure of the Spanish hotel industry: Evidence from cluster analysis”, Tour. Econ., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 121–138, 2009, doi:10.5367/000000009787536690. |

| O. Pavlatos and I. Paggios, “Activity-based costing in the hospitality industry: Evidence from Greece”, J. Hosp. Tour. Res., vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 511–527, 2009, doi:10.1177/1096348009344221. |

| O. Pavlatos and I. Paggios, “A survey of factors influencing the cost system design in hotels”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 263–271, 2009, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.09.002. |

| O. Pavlatos and I. Paggios, “Management accounting practices in the Greek hospitality industry”, Manag. Audit. J., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 81–98, 2009, doi:10.1108/02686900910919910. |

| C. Raab, K. Mayer, S. Shoemaker, and S. Ng, “Activity-based pricing: Can it be applied in restaurants?”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 393–410, 2009, doi:10.1108/09596110910955668. |

| X. L. Wang and D. Bowie, “Revenue management: The impact on business-to-business relationships”, J. Serv. Mark., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 31–41, 2009, doi:10.1108/08876040910933075. |

| S. Zounta and M. G. Bekiaris, “Cost-based management and decision-making in Greek luxury hotels”, Tourismos, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 205–225, 2009. |

| I. Dalci, V. Tanis, and L. Kosan, “Customer profitability analysis with time-driven activity-based costing: A case study in a hotel”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 609–637, 2010, doi:10.1108/09596111011053774. |

| P. Vaughn, C. Raab, and K. B. Nelson, “The application of activity-based costing to a support kitchen in a Las Vegas casino”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 1033–1047, 2010, doi:10.1108/09596111011066662. |

| J. Chen, Y. Koh, and S. Lee, “Does the market care about RevPAR? A case study of five large U.S. lodging chains”, J. Hosp. Tour. Res., vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 258–273, 2011, doi:10.1177/1096348010384875. |

| O. Pavlatos, “The impact of strategic management accounting and cost structure on ABC systems in hotels”, J. Hosp. Financ. Manag., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 37–55, 2011, doi:10.1080/10913211.2011.10653912. |

| R. Sainaghi, “RevPAR determinants of individual hotels: Evidences from Milan”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 297–311, 2011, doi:10.1108/09596111111122497. |

| A. R. Faria, D. Trigueiros, and F. Leonor, “Práticas de Custeio e Controlo de Gestão no Sector Hoteleiro do Algarve/Costing and Management Control Practices in the Algarve Hotel Sector”, Tour. Manag. Stud., no. 8, pp. 100–107, Jan. 2012. |

| D. Kosarkoska and I. Mircheska, “Uniform system of accounts in the lodging industry (USALI) in creating a responsibility accounting in the hotel enterprises in Republic of Macedonia”, Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci., vol. 44, pp. 114–124, Jan. 2012, doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.011. |

| L. Lima Santos, C. Gomes, and N. Arroteia, “Management accounting practices in the Portuguese lodging industry”, J. Mod. Account. Audit., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Jan. 2012. |

| S. Ni, W. Chan, and K. Wong, “Enhancing the Applicability of Hotel Uniform Accounting in Hong Kong.”, Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res., vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 177–192, Apr. 2012, doi:10.1080/10941665.2011.616904. |

| X. Wang, “Relationship or revenue: Potential management conflicts between customer relationship management and hotel revenue management”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 864–874, 2012, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.10.005. |

| X. Wang, “The impact of revenue management on hotel key account relationship development”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 358–380, 2012, doi:10.1108/09596111211217860. |

| A. Ebimobowei and B. Binaebi, “Analysis of Factors Influencing Activity-Based Costing Applications in the Hospitality Industry in Yenagoa, Nigeria”, Asian J. Bus. Manag., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 284–290, 2013, doi:10.19026/ajbm.5.5324. |

| U. Grissemann, A. Plank, and A. Brunner-Sperdin, “Enhancing business performance of hotels: The role of innovation and customer orientation”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 347–356, 2013, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.10.005. |

| L. McManus, “Customer accounting and marketing performance measures in the hotel industry: Evidence from Australia”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 140–152, 2013, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.07.007. |

| B. Basuki and M. D. Riediansyaf, “The Application of Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing In the Hospitality Industry: An Exploratory Case Study”, J. Appl. Manag. Account. Res., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 27–54, 2014. |

| S. Bresciani, A. Thrassou, and D. Vrontis, “Determinants of performance in the hotel industry—An empirical analysis of Italy”, Glob. Bus. Econ. Rev., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 19–34, 2015, doi:10.1504/GBER.2015.066531. |

| O. Pavlatos, “An empirical investigation of strategic management accounting in hotels”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 756–767, 2015. |

| S. Rushmore and J. W. O’Neill, “Updated benchmarks for projecting fixed and variable components of hotel financial performance”, Cornell Hosp. Q., vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 17–28, 2015, doi:10.1177/1938965514538314. |

| S. Bangchokdee and L. Mia, “The role of senior managers’ use of performance measures in the relationship between decentralization and organizational performance Evidence from hotels in Thailand”, J. Account. Organ. Chang., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 129–151, 2016, doi:10.1108/JAOC-11-2012-0110. |

| F. Campa-Planas and L. C. Banchieri, “Study about homogeneity implementing USALI in the hospitality business”, Cuad. Tur., vol. 0, no. 37, pp. 17–35, 2016, doi:10.6018/turismo.37.256521. |

| R. Linassi, A. Alberton, and S. V. Marinho, “Menu engineering and activity-based costing: An improved method of menu planning”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 1417–1440, 2016, doi:10.1108/IJCHM-09-2014-0438. |

| G. Makrygiannakis and L. Jack, “Understanding management accounting change using strong structuration frameworks”, Accounting, Audit. Account. J., vol. 29, no. 7, pp. 1234–1258, 2016, doi:10.1108/AAAJ-08-2015-2201. |

| A. Patiar, “Costs allocation practices: Evidence of hotels in Australia”, J. Hosp. Tour. Manag., vol. 26, pp. 1–8, Mar. 2016, doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2015.09.002. |

| C. A. F. Amado, S. P. Santos, and J. M. M. Serra, “Does partial privatisation improve performance? Evidence from a chain of hotels in Portugal”, J. Bus. Res., vol. 73, pp. 9–19, 2017, doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.12.001. |

| F. Campa-Planas, L.-C. L. C. Banchieri, and N. Kalemba, “A study of the uniformity of the USALI methodology in Spain and Catalonia”, Tourism, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 204–217, 2017. |

| R. Lado-Sestayo, M. Vivel-Búa, and L. Otero-González, “Determinants of TRevPAR: Hotel, management and tourist destination”, Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 29, no. 12, pp. 3138–3156, 2017, doi:10.1108/IJCHM-03-2016-0151. |

| O. Silva, M. Macas, and M. J. Espinosa, “Accounting control rules: essential operation in business management: an ecuadorian case”, Univ. y Soc., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 46–51, 2017. |

| M. J. Turner, S. A. Way, D. Hodari, and W. Witteman, “Hotel property performance: The role of strategic management accounting”, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., vol. 63, pp. 33–43, 2017, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.02.001. |

| A. Faria, L. Ferreira, and D. Trigueiros, “Analyzing customer profitability in hotels using activity-based costing”, Tour. Manag. Stud., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 65–74, 2018, doi:10.18089/tms.2018.14306. |

| S. Y. Kim, “Predicting hospitality financial distress with ensemble models: The case of US hotels, restaurants, and amusement and recreation.”, Serv. Bus., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 483–503, Sep. 2018. |

| J. Gomez-Conde, R. J. Lunkes, and F. S. Rosa, “Environmental innovation practices and operational performance: The joint effects of management accounting and control systems and environmental training”, Accounting, Audit. Account. J., vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 1325–1357, 2019, doi:10.1108/AAAJ-01-2018-3327. |

| R. Lunkes, D. Bortoluzzi, M. Anzilago, and F. Rosa, “Influence of online hotel reviews on the fit between strategy and use of management control systems: A study among small- and medium-sized hotels in Brazil”, J. Appl. Account. Res., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 615–634, Nov. 2020, doi:10.1108/JAAR-06-2018-0090. |

| G. Karanović, A. Štambuk, and D. Jagodić, “Profitability Performance Under Capital Structure and Other Company Characteristics: An Empirical Study of Croatian Hotel Industry”, Zb. Veleučilišta u Rijeci, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 227–242, 2020. |

| M. Yasir, A. Amir, R. Maelah, and A. Nasir, “Establishing Customer Knowledge Through Customer Accounting in Tourism Industry: A Study of Hotel Sector in Malaysia”, Asian J. Account. Gov., vol. 14, pp. 155–165, 2020, doi:10.17576/ajag-2020-14-12. |

References

- Atkinson, H.; Brown, J. Rethinking performance measures: Assessing progress in UK hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amat, O.; Campa, F. Contabilidad, Control de Gestion y Finanzas de Hotels; Profit: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lamelas, J.P. Sistema Uniforme de Contabilidade Analítica de Gestão Hoteleira um Estudo de Caso, 1st ed.; Vislis Editores: Lisbon, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pajrok, A. Application of target costing method in the hospitality industry. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2014, 5, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H. The dismissal of information technology opportunities in the management accounting of small medium-sized tourism enterprise: A research note. Smart Innov. Syst. Technol. 2021, 209, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R.H. Management control systems design within its organizational context: Findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future. Account. Organ. Soc. 2003, 28, 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.; Macedo, J.; Moreira, A.; Isidro, H. Práticas de Contabilidade Financeira; Áreas: Lisbon, Portugal, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, L.; Gomes, C.; Faria, A.R.; Lunkes, R.J.; Malheiros, C.; Silva da Rosa, F.; Nunes, C. Contabilidade de Gestão Hoteleira, 1st ed.; ATF—Edições Técnicas: Cacém, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, M.; Sharma, K. Understanding the importance of management accounting practices in Indian hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2020, 13, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, A. Management Accounting Systems in the Algarve Hotel Sector: Plan or Improvise? Ph.D. Thesis, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, L.; Gomes, C.; Arroteia, N. Management accounting practices in the Portuguese lodging industry. J. Mod. Account. Audit. 2012, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, A.; Ferreira, L.; Trigueiros, D. Orçamentação nos hotéis do Algarve: Alinhamento com a prática internacional. Dos Algarves Multidiscip. e-J. 2019, 34, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, T.; Lindsay, R.M. Beyond budgeting or budgeting reconsidered? A survey of North-American budgeting practice. Manag. Account. Res. 2010, 21, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, R.; Govindarajan, V. Management Control Systems, 10th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, C.; Arroteia, N.; Lima Santos, L. Management accounting in Portuguese hotel enterprises: The influence of organizational and cultural factors. In Fulfilling the Worldwide Sustainability Challenge: Strategies, Innovations, and Perspectives for Forward Momentum in Turbulent Times, Proceedings of the 13th Annual International Conference of the Global Business and Technology Association, Istanbul, Turkey, 12–16 July 2011; Global Businness and Technology Association: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, C.; Lima Santos, L.; Arroteia, N. The influence of the environmental and organizational factors in the management accounting of the Portuguese hotels. In Proceedings of the VII Congreso Iberoamericano de Contabilidad de Gestión y IX Congreso Iberoamericano de Administración Empresarial y Contabilidad, Valencia, Spain, 3–5 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.; Quinn, M.; Warren, L.; Oliveira, J. Management Accounting, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, I. How might hospitality organizations optimize their performance measurement systems? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunkes, R.J. Manual de Contabilidade Hoteleira, 1st ed.; Editora Atlas, S.A.: São Paulo, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brierley, J.A.; Cowton, C.J.; Drury, C. Research into product costing practice: A European perspective. Eur. Account. Rev. 2001, 10, 215–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounta, S.; Bekiaris, M.J. Cost-based management and decision-making in Greek luxury hotels. Tourismos 2009, 4, 205–225. [Google Scholar]

- ProductPlan. Product Profitability. 2021. Available online: https://www.productplan.com/glossary/product-profitability/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Makrigiannakis, G.; Soteriades, M. Management accounting in the hotel business: The case of the Greek hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2007, 8, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Santos, L.; Gomes, C.; Arroteia, N.; Almeida, P. The perception of management accounting in the Portuguese lodging industry. In Managing in an Interconnected World: Pioneering Business and Technology Excellence, Proceedings of the 16th Annual International Conference of the Global Business and Technology Association, Baku, Zaerbaijan, 8–12 July 2014; Global Business and Technology Association: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 565–572. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, F. O ‘Uniform System of Accounts for the Lodging Industries’: Case Study Hotel Baía. Master’s Thesis, ISCTE Business School, Repositório ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, P.; Moutinho, L. Critical review of strategic planning research in hospitality and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunkes, R.; Bortoluzzi, D.; Anzilago, M.; Rosa, F. Influence of online hotel reviews on the fit between strategy and use of management control systems: A study among small- and medium-sized hotels in Brazil. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2020, 21, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezet, A. The history of the French tableau de bord (1885–1975): Evidence from the archives. Account. Bus. Financ. Hist. Taylor Fr. 2009, 19, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Najdawi, B.M. Performance measurement system approaches in hotel industry: A comparative study. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 3504–3507. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, M.; Sharma, K. Management accounting practices in Indian and Canadian hotel industry: A comparative study. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2021, 14, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Quesado, P.R.; Rodrigues, L.L.; Guzmán, B.A. The tableau de bord and the balanced scorecard: A comparative analysis. Rev. Contab. Control. 2012, 4, 128–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-hosban, A.; Alsharairi, M.; Al-Tarawneh, I. The effect of using the target cost on reducing costs in the tourism companies in Aqaba special economic zone authority. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. Management Accounting and Control Systems Design and Use: An Exploratory Study in Portugal; The Management School, Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Adamu, A.; Olotu, I.A. The practicability of activity-based costing system in hospitality industry. J. Financ. Account. Res. 2009, 1, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosarkoska, D.; Mircheska, I. Uniform system of accounts in the lodging industry (USALI) in creating a responsibility accounting in the hotel enterprises in Republic of Macedonia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faria, A.; Ferreira, L.; Trigueiros, D. Analyzing customer profitability in hotels using activity-based costing. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2018, 14, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester-Miguel, J.; Pérez-Ruiz, P.; Hernández-Gadea, J.; Palacios-Marques, D. Implementation of the balance scorecard in the hotel sector through transformational leadership and empowerment. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Soc. Technol. Sci. 2016, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M.C.; Wang, W.K.; Huang, H.C.; Kao, M.C. Linking the benchmarking tool to a knowledge-based system for performance improvement. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 10579–10586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, B.; D’Lima, C. Benchmarking as a measure of competitiveness. Int. J. Process Manag. Benchmark. 2014, 4, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiansyah, G.B.; Tjahjadi, B.; Soewarno, N. Measuring customer profitability through time-driven activity-based costing: A case study at Hotel X Jogjakarta. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of the Asian Academic Accounting Association (2016 FourA Conference), Kuching Sarawak, Malaysia, 20–22 November 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, T.; Atkinson, H.; Lorenz, A.; Harris, P. Strategic Managerial Accounting: Hospitality, Tourism & Events, 6th ed.; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, A.; Suri, K. Customer profitability analysis: An avant-garde approach to revenue optimisation in hotels. Int. J. Revenue Manag. 2012, 6, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Amir, A.; Maelah, R.; Nasir, A. Establishing Customer Knowledge through Customer Accounting in Tourism Industry: A Study of Hotel Sector in Malaysia. Asian J. Account. Gov. 2020, 14, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trandafir, R.-A. The economic value-added (EVA): A measurement indicator of the value creation within a company from the Romanian seaside hotel industry. Ann. Constantin Brâncuşi Univ. Târgu Jiu Econ. Ser. 2015, 1, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Balteș, N.; Pavel, R.-M. Study on the correlation between working capital and economic value added for the companies relating to the hotel and restaurant industry listed on the bucharest stock exchange. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2020, 20, 838–844. [Google Scholar]

- Kratz, N.; Kroflin, P. The relevance of net working capital for value-based management and its consideration within an economic value-added (EVA) framework. J. Econ. Manag. 2016, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Caiado, A.C.P. Contabilidade Analítica e de Gestão, 5th ed.; Áreas Editora: Lisbon, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, A. Life Cycle Costing: Meaning, Characteristics and Everything Else. Accounting Notes. 2019. Available online: https://www.accountingnotes.net/cost-accounting/life-cycle-costing/life-cycle-costing-meaning-characteristics-and-everything-else/5783 (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Aladwan, M.; Alsinglawi, O.; Alhawatmeh, O. The applicability of target costing in jordanian hotels industry. Acad. Account. Financ. Stud. J. 2018, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, L.P.M.M. Rentabilidade Expectável de um Boutique Hotel em Lisboa; Estoril Higher Institute of Hotel Management and Tourism: Estoril, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Urquidi-Martin, A.; Ripoll Feliu, V. The choice of management accounting techniques in the hotel sector: The role of contextual factors. J. Manag. Res. 2013, 5, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slattery, P. Reported RevPAR: Unreliable measures, flawed interpretations and the remedy. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 21, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casqueira, N.; Gomes, C.; Lima Santos, L.; Malheiros, C.; Ferreira, R.R. Performance evaluation of small independent hotels through management accounting indicators and ratios. In Proceedings of the EATSA Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 26–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, C.; Lima Santos, L.; Malheiros, C.; Cardoso, P. Setting up operating indicators and ratios for independent hotels. In Proceedings of the IX International Tourism Congress (ITC’17), Peniche, Portugal, 29–30 November 2017; pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, L.; Malheiros, C.; Gomes, C.; Guerra, T. TRevPAR as hotels performance evaluation indicator and influencing factors in Portugal. EATSJ Euro-Asia Tour. Stud. J. 2020, 1, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mašić, S.I. The performance of Serbian hotel industry. Singidunum J. Appl. Sci. 2013, 10, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lima Santos, L.; Cardoso, L.; Araújo-Vila, N.; Fraiz-Brea, J.A. Sustainability perceptions in tourism and hospitality: A mixed-method bibliometric approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Hotel & Lodging Association. Uniform System of Accounts for the Lodging Industry, 11th ed.; American Hotel & Lodging Association: Lansing, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, A.C. The uniform system of accounts for the lodging industry and XBRL: Development and exchange of homogeneous information. In Research Studies on Tourism and Environment; Jimenez, M., Ferrari, G., Vargas, M., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidgall, R.S.; Defranco, A. Uniform system of accounts for the lodging industry, 11th revised edition: The new guidelines for the lodging insdustry. J. Hosp. Financ. Manag. 2015, 23, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yalcin, S. Adoption and benefits of management accounting practices: An inter-country comparison. Account. Eur. 2012, 9, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The art of writing a literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudarra-Fernández, A.; Carrillo-Hidalgo, J.; Fernández, I. Factors influencing tourist expenditure by tourism typologies: A systematic review. Anatolia 2018, 30, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In EASE ’14, Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, London, UK, 13–14 May 2014; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Arcodia, C. A systematic literature review of risk and gender research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Kulykovets, O. Hotel brand loyalty—A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, N.; Do Céu Alves, M.; Martins, I. The impacts of emerging technologies on accountants’ role and skills. Connecting to open innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardoso, L.; Araújo-Vila, N.; Soliman, M.; Araújo, A.F.; Almeida, G.G.F. How to employ Zipf’s laws for content analysis in tourism studies. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2022, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Molinos, D.; Hoff, M.D.D. ZipfTool: Uma ferramenta bibliométrica para auxílio na pesquisa teórica. Rev. Inf. Teór. Apl. 2016, 23, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardoso, L.; Dias, F.; Araújo, A.; Marques, M. A destination imagery processing model: Structural differences between dream and favourite destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.; Araújo, A.F.; Lima Santos, L.; Schegg, R.; Breda, Z.; Costa, C. Country performance analysis of swiss tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O.; Paggios, I. Management accounting practices in the Greek hospitality industry. Manag. Audit. J. 2009, 24, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, T. Improving hotel budgetary practice—A positive theory model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, L.; Patiar, A. The interactive effect of superior-subordinate relationship and budget participation on managerial performance in the hotel industry: An exploratory study. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2002, 26, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.S. The differential effect of environmental dimensionality, size, and structure on budget system characteristics in hotels. Manag. Account. Res. 2002, 13, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O.; Paggios, I. A survey of factors influencing the cost system design in hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, L.; Patiar, A. The use of management accounting systems in hotels: An exploratory study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 20, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Upneja, A. Factors influencing financial performance of small hotels in Tanzania. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiar, A.; Mia, L. The interactive effect of market competition and use of MAS information on performance: Evidence from the upscale hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M.J.S.; Esteban, L.P.; Martínez, A.G. The financial structure of the Spanish hotel industry: Evidence from cluster analysis. Tour. Econ. 2009, 15, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Koh, Y.; Lee, S. Does the market care about RevPAR? A case study of five large U.S. lodging chains. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2011, 35, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, C.A.F.; Santos, S.P.; Serra, J.M.M. Does partial privatisation improve performance? Evidence from a chain of hotels in Portugal. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 73, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lado-Sestayo, R.; Vivel-Búa, M.; Otero-González, L. Determinants of TRevPAR: Hotel, management and tourist destination. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3138–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y. Predicting hospitality financial distress with ensemble models: The case of US hotels, restaurants, and amusement and recreation. Serv. Bus. 2018, 12, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa-Planas, F.; Banchieri, L.-C.; Kalemba, N. A study of the uniformity of the USALI methodology in Spain and Catalonia. Tourism 2017, 65, 204–217. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlatos, O. The impact of strategic management accounting and cost structure on ABC systems in hotels. J. Hosp. Financ. Manag. 2011, 19, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rushmore, R.; O’Neill, J.W. Updated benchmarks for projecting fixed and variable components of hotel financial performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 56, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raab, C.; Mayer, K.J. Exploring the use of activity-based costing in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2004, 4, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, C.; Mayer, K.; Ramdeen, C.; Ng, S. The application of activity-based costing in a Hong Kong buffet restaurant. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2005, 6, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, C.; Shoemaker, S.; Mayer, K. Activity-based costing: A more accurate way to estimate the costs for a restaurant menu. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2007, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annaraud, K.; Raab, C.; Schrock, J.R. The application of activity-based costing in a quick service restaurant. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2008, 11, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O.; Paggios, I. Activity-based costing in the hospitality industry: Evidence from Greece. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalci, I.; Tanis, V.; Kosan, L. Customer profitability analysis with time-driven activity-based costing: A case study in a hotel. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 609–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangchokdee, S.; Mia, L. The role of senior managers’ use of performance measures in the relationship between decentralization and organizational performance Evidence from hotels in Thailand. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2016, 12, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Conde, J.; Lunkes, R.J.; Rosa, F.S. Environmental innovation practices and operational performance: The joint effects of management accounting and control systems and environmental training. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 1325–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, L. Customer accounting and marketing performance measures in the hotel industry: Evidence from Australia. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karanović, G.; Štambuk, A.; Jagodić, D. Profitability performance under capital structure and other company characteristics. Zb. Veleuč. u Rijeci 2020, 8, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O.; Paggios, I. Cost accounting in Greek hotel enterprises: An empirical approach. Tourismos 2007, 2, 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N. Assessing the balanced scorecard as a management tool for hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.; Louvieris, P. Performance measurement systems in tourism, hospitality, and leisure small medium-sized enterprises: A balanced scorecard perspective. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.R.; Trigueiros, D.; Ferreira, L. Práticas de custeio e controlo de gestão no sector hoteleiro do Algarve. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2012, 8, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, S.; Chan, W.; Wong, K. Enhancing the Applicability of Hotel Uniform Accounting in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa-Planas, F.; Banchieri, L.C. Study about homogeneity implementing USALI in the hospitality business. Cuad. Tur. 2016, 37, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patiar, A. Costs allocation practices: Evidence of hotels in Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capiez, A.; Kaya, A. Yield management and performance in the hotel industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 16, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Yasir, M.; Majid, A. Promoting employees’ environmental performance in hospitality industry through environmental attitude and ecological behavior: Moderating role of managers’ environmental commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 3006–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyide, C.J. Better resource management: A qualitative investigation of Environmental Management Accounting practices used by the South African hotel sector. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Tarí, J.J.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Pertusa-Ortega, E.M. The effects of quality and environmental management on competitive advantage: A mixed methods study in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Reason for Inclusion or Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusion criteria | ||

| No full text | NFT | No full text |

| Not related 1 | NR-1 | Books or book chapters, not considered papers |

| Not related 2 | NR-2 | Studies not based on empirical research |

| Not related 3 | NR-3 | Papers published as “short papers” |

| Loosely related 1 | LR-1 | Studies based on environmental management |

| Loosely related 2 | LR-2 | Studies describing management accounting not related to hospitality |

| Loosely related 3 | LR-3 | Studies that do not contribute to the literature to improve knowledge about hotels, management accounting, and USALI |

| Inclusion criteria | ||

| Totally related 1 | TR -1 | Studies that contribute to the literature to improve knowledge about hotels, management accounting, and USALI |

| Totally related 2 | TR -2 | Studies based on empirical research |

| Totally related 3 | TR -3 | Studies with (a) well-defined research objective(s) |

| Ranking | Variable Name | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency | Ranking | Variable Name | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | hotel | 124 | 0.017913898 | 19 | using | 27 | 0.003900607 |

| 2 | performance | 101 | 0.014591158 | 20 | also | 26 | 0.003756140 |

| 3 | management | 97 | 0.014013291 | 20 | based | 26 | 0.003756140 |

| 4 | hotels | 87 | 0.012568622 | 20 | costing | 26 | 0.003756140 |

| 5 | study | 82 | 0.011846287 | 20 | key | 26 | 0.003756140 |

| 6 | accounting | 67 | 0.009679283 | 21 | profitability | 25 | 0.003611673 |

| 6 | research | 67 | 0.009679283 | 21 | system | 25 | 0.003611673 |

| 7 | industry | 57 | 0.008234615 | 22 | hospitality | 24 | 0.003467206 |

| 8 | paper | 51 | 0.007367813 | 22 | not | 24 | 0.003467206 |

| 8 | results | 51 | 0.007367813 | 22 | relationship | 24 | 0.003467206 |

| 9 | managers | 48 | 0.006934412 | 23 | practice | 23 | 0.003322739 |

| 10 | ABC | 46 | 0.006645478 | 23 | survey | 23 | 0.003322739 |

| 10 | cost | 46 | 0.006645478 | 23 | traditional | 23 | 0.003322739 |

| 11 | financial | 43 | 0.006212078 | 24 | can | 22 | 0.003178272 |

| 12 | data | 42 | 0.006067610 | 24 | has | 22 | 0.003178272 |

| 13 | analysis | 41 | 0.005923144 | 25 | costs | 21 | 0.003033805 |

| 14 | between | 40 | 0.005778677 | 26 | evidence | 20 | 0.002889338 |

| 15 | customer | 39 | 0.005634210 | 26 | other | 20 | 0.002889338 |

| 16 | findings | 30 | 0.004334007 | 26 | purpose | 20 | 0.002889338 |

| 17 | revenue | 29 | 0.004189541 | 27 | approach | 19 | 0.002744871 |

| 17 | used | 29 | 0.004189541 | 27 | business | 19 | 0.002744871 |

| 18 | practices | 28 | 0.004045074 | 27 | literature | 19 | 0.002744871 |

| 18 | systems | 28 | 0.004045074 | 27 | structure | 19 | 0.002744871 |

| 19 | measures | 27 | 0.003900607 | 27 | such | 19 | 0.002744871 |

| 19 | restaurant | 27 | 0.003900607 | 28 | activity-based | 18 | 0.002600404 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campos, F.; Lima Santos, L.; Gomes, C.; Cardoso, L. Management Accounting Practices in the Hospitality Industry: A Systematic Review and Critical Approach. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 243-264. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010017

Campos F, Lima Santos L, Gomes C, Cardoso L. Management Accounting Practices in the Hospitality Industry: A Systematic Review and Critical Approach. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(1):243-264. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampos, Filipa, Luís Lima Santos, Conceição Gomes, and Lucília Cardoso. 2022. "Management Accounting Practices in the Hospitality Industry: A Systematic Review and Critical Approach" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 1: 243-264. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010017

APA StyleCampos, F., Lima Santos, L., Gomes, C., & Cardoso, L. (2022). Management Accounting Practices in the Hospitality Industry: A Systematic Review and Critical Approach. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(1), 243-264. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010017