Abstract

This study examines residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia, focusing on its benefits and costs, guided by social exchange theory. The objective is to explore how the perceived impacts of tourism development, along with external factors such as community attachment, residents’ knowledge of tourism development, and community involvement, affect locals’ satisfaction with tourism and their intention to support tourism development. A survey of 427 locals, analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM), reveals a positive correlation between community attachment and the perceived benefits from tourism. Residents’ knowledge about tourism is linked to perceived benefits, but not to perceived costs, and community involvement does not significantly impact perceptions. Perceived benefits positively influence support for tourism, while perceived costs have a negative effect. Residents’ satisfaction with tourism, shaped by their perceptions of the benefits and costs, influences their future support for tourism initiatives. The theoretical implications highlight social exchange theory’s role in understanding community perceptions, while the practical implications emphasize inclusive and transparent tourism planning to gain local support. These results underscore the importance of considering locals’ perceptions and satisfaction in both current and future tourism planning and development strategies.

1. Introduction

Tourism is considered an essential source of economic growth worldwide, and many countries have focused on tourism activities as an important source of foreign exchange [1,2,3]. Numerous scholars have intensively investigated the economic aspects of tourism, including Alfaro Navarro et al. [4], Bekun et al. [5], Calero and Turner [6], and Nunkoo et al. [7], among many others. These scholars have concluded that the most important reasons for governments, the private sector, and tourism businesses to develop tourism are its related economic benefits. Tourism has become a global phenomenon, widely recognized at the national level as one of the fastest-growing sectors in the world economy, with the potential for raising tax revenues, providing employment opportunities, and promoting economic diversity. It has also been suggested that it can preserve local heritage, improve infrastructure, and provide better local facilities, and thus better lifestyles, for the local population [8,9].

However, it is generally understood that tourism development for host communities can be a double-edged sword [10]. Tourism development provides advantages and can generate costs [11]. Suppose tourism ventures are not properly organized and executed. In this case, such pursuits can lead to the destruction of flora and fauna, the creation of congestion, the pollution of beaches, and overbuilding [12,13]. Tourism ventures must take care to preserve and protect the environment and the natural attractions of an area; however, there exist concerns about how this can be achieved. There is wide agreement on the fact that tourism strategies must reflect an understanding of sustainable tourism development. This requires governments to be fully knowledgeable about the tourism industry and understand its impacts on society [14]. Locals are the main actors in sustainable tourism development. Local communities play an essential role in the sustainability of tourism in general (and tourism development in particular); these communities are affected by tourism and are the beneficiaries of tourism development [1].

Based on the number of advantages and disadvantages that residents experience because of tourism, they will have different views about the impact of tourism on their society [14]. If residents have a favorable view of tourism, they will encourage and support its development. However, if local people think that the development of tourism will bring more drawbacks than advantages, they are likely to resist tourism development. Therefore, any tourism development without residents’ involvement and cooperation in planning will be endangered [15].

Studies on locals’ perceptions of tourism growth are increasing due to the link between community support and the potential development of tourism [16,17]. Locals’ perceptions must be considered for tourism to grow sustainably. When planning for tourism development, decision-makers need to consider locals’ participation in tourism development. Since local participation occupies a vital role in the success of sustainable tourism development, knowing how residents view tourism impacts offer valuable insights for scholars, policymakers, and service providers, contributing to knowledge about how best to develop tourism in a community [18]. Taking locals’ perceptions into account helps governments better advance tourism activities in their communities. The different perceptions of locals can also illustrate the consequences that come with the arrival of tourists [19].

Solid societal support for tourism is necessary for the tourism industry’s sustainable development [20,21]. The degree to which the residents’ perceptions are properly considered determines their support for tourism development [17,22]. Understanding locals’ perceptions about tourism development and its impacts can enable planners and developers to identify serious issues, setting effective policies that maximize the benefits and minimize the problems generated by tourism development [17,23].

Harrill [24] notes that most research has concentrated on assessing the perceptions of locals after tourism development has become established in the destination, indicating that residents were already somewhat familiar with the development. Moreover, Mason and Cheyne [25] and Lepp [26] also pointed out that most of the research carried out since the mid-1970s investigated the perceived impacts of tourism on locals when tourism development in the host country had been economically valuable. On their part, Harrill [24] and Çelik and Rasoolimanesh [11] stressed the need to examine residents’ attitudes in communities that are still in the development stage of tourism, especially in emerging destinations.

Many studies have taken place in developed tourism destinations or in destinations where their residents rely heavily on tourism as an essential source of income, such as islands and rural and small urban destinations [23,27,28,29,30,31]. However, there are limited studies that have been conducted on emerging destinations [32,33,34]. Sinclair-Maragh and Gursoy [35] suggest that the theoretical background of residents’ attitudes toward tourism should be strengthened by analyzing various geographical areas with different political contexts.

Despite the growing interest in tourism development in emerging destinations, there is a notable gap in the understanding of residents’ perceptions regarding its effects. The literature lacks comprehensive insights into how these perceptions influence the planning and execution of tourism strategies in these areas. Consequently, there is a pressing need for research that addresses these concerns, providing valuable insight for academics, local planners, business owners, and tourism promoters.

This study seeks to identify how the perceived impacts of tourism affect locals’ satisfaction with and support for tourism development, and, in turn, how locals’ satisfaction with tourism affects their intention to support tourism development in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia. In the following section, the context of the study is developed. Then, in the third section, the pertinent literature is examined to formulate the conceptual model and the corresponding hypotheses. In the fourth section, the methodology is explained. Then, the results are presented, and finally, the discussion and conclusions are drawn.

2. The Context of the Study

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, has leveraged its investment power to diversify and build a sustainable economy following the launch of Vision 2030 [36]. Announced by King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud on 25 April 2016, Vision 2030 aims to diversify the economy and develop public sectors, including education, health, recreation, and tourism, aligning with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [37]. The tourism sector is central to Vision 2030, with projects like the Red Sea Project, Al-Ula (Sharan), NEOM, Qiddiya, and Diriyah Gate aiming to attract global and local investment [38]. Riyadh’s initiatives focus on environmental preservation, energy conservation, and cultural promotion, enhancing its role as an economic, financial, tourism, and entertainment hub.

For Vision 2030’s success, understanding local attitudes toward tourism development is crucial [39]. Tourism beyond religious pilgrimage is relatively new in the Kingdom, particularly in Riyadh. Historically, religious tourism has dominated due to Saudi Arabia’s significance as a pilgrimage destination, while other forms, such as sports, cultural, and leisure tourism, have been secondary [40]. The government’s goal is to diversify tourism to maximize returns, attract tourists, and reduce oil dependency [36,41,42]. Scholars note that developing tourism can create jobs, improve infrastructure, and enhance public transit [43]. Tourism can also boost national pride, increase cultural awareness, and present a hospitable global image [44]. Assessing residents’ perceptions before and during tourism development is essential for aligning policies with community desires and ensuring sustainable tourism growth [45].

This study is distinct in its focus on Riyadh, an emerging tourism destination under Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. Riyadh is undergoing rapid transformation with significant investments in sustainable tourism projects, such as King Salman Park, Qiddiya, and Diriyah Gate, aimed at diversifying the economy and enhancing the quality of life. Despite these developments, there remains a notable gap in the understanding of local residents’ perceptions of these changes, which is crucial for sustainable tourism growth. Unlike other studies that concentrate on well-established tourist destinations, this research uniquely examines Riyadh, providing valuable insights into how residents perceive and support tourism development in a city transitioning from predominantly religious tourism to a more diversified tourism sector.

An in-depth review of journal databases and the academic literature reveals a scarcity of studies with a theoretical basis measuring the perceptions of Riyadh residents regarding tourism development impacts and their support intentions. Additionally, there are limited studies that examine how factors such as community attachment, residents’ knowledge, and community involvement influence these perceptions, nor how perceived tourism impacts affect locals’ satisfaction and support for tourism development. This study aims to fill these gaps by exploring how community attachment, residents’ knowledge, and community involvement influence perceptions of tourism impacts in Riyadh. The research questions driving this study are as follows:

- How do the perceived impacts of tourism development affect locals’ satisfaction with tourism and their intention to support tourism development in Riyadh city?

- How do the perceived impacts of tourism development affect locals’ intention to support tourism development in Riyadh city?

- How do external factors (e.g., community attachment, residents’ knowledge of tourism development, community involvement) affect locals’ perceptions of tourism development and its impacts in Riyadh city?

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

Tourism development induces numerous economic, sociocultural, and environmental changes in the life of the host community [46,47,48]. Therefore, the involvement and support of residents at any destination are essential for the sustainability of the tourism industry [39]. Understanding the viewpoint of residents will promote policies that mitigate and optimize the possible negative impacts of tourism development, thereby contributing to community development and greater support for tourism development [49]. There is a strong consensus that social exchange theory (SET) is an acceptable framework used to establish an understanding of the perceptions of tourism among residents [50,51,52,53,54,55].

Social exchange theory (SET) has been used as a theoretical basis to help explain locals’ perceptions of tourism development [27] and to examine the support for tourism development by locals [52,56]. The theory of social exchange can anticipate the attitude of residents toward tourism impacts, and it could be used to understand different perceptions toward tourism development. SET explores economic, environmental, and sociocultural aspects and then decides how residents react to tourism’s current and future development [23].

In tourism research, social exchange theory (SET) is used, among other theories, to understand the causal relationship between the perceived benefits/costs of tourism development and the residents’ support for tourism development [53,57,58,59]. For example, some studies have concluded that local people are likely to support tourism development if they view its impact positively, and vice versa [35,60]. To elaborate, if residents from specific destinations recognize the economic, social, cultural, and environmental benefits of tourism, they will support tourism development. In contrast, residents who perceive the impact of tourism as a cost to their economy, society, culture, and environment will probably be more opposed to the development of tourism [59,61,62,63,64]. Therefore, in this study, SET explains residents’ attitudes toward tourism development and its impacts in Riyadh city.

In the literature, three main approaches to SET are commonly used, namely, the cost–benefit, domain-related, and non-forced approaches, with the cost–benefit approach given priority [11,65]. Effectively, the most prevalent approach in these types of studies is the cost–benefit approach due to its simplicity and clarity [46,59]. Studies following this approach group the potential impacts of tourism into costs and benefits (or negative and positive impacts), generally indicating a direct negative relationship between the perceived costs and the support for tourism development and a direct positive relationship between the perceived benefits and support [46,66]. Thus, the most prevalent approach (the cost–benefit approach) is used in this study.

3.2. Communities’ Perceptions of Tourism Development and Its Impacts

The impact of tourism development can be examined from a variety of perspectives, including the economic, sociocultural, and environmental perspectives. Tourism development also has social consequences, which can be positive or negative [20,48]. Many local communities have identified that tourism may encourage changes in economic, environmental, social, and cultural dimensions, particularly when tourism development activities are closely linked to local communities. An awareness of community attitudes and perceptions, as well as how these perceptions are created, is valuable for decision-makers in sustainable tourism development.

The community is the most significant party because tourism planning and development will have a positive or negative impact on it [67]. According to Gursoy et al [61], there is a significant positive association between community involvement in tourism development and community perceptions of the impacts of tourism development. Local communities’ perceptions influence their support for tourism. As a result, analyzing residents’ attitudes toward tourism is critical for successful and sustainable tourism development [35,46,50,57,68,69].

Local communities that are exposed to tourism development may develop diverse opinions of tourists, their behaviors, and the consequences of their actions. For example, some residents may believe that certain tourism activities damage the local culture, while others may believe that tourism benefits society. The local community will also act differently depending on their perceptions, which might be positive or negative [67]. Kuvan and Akan [70] studied the attitudes of Turkish people toward the economic, social, and environmental impacts of tourism. It was shown that locals had developed positive attitudes toward the area’s tourism development. In addition, a study conducted by Lepp [26] discovered a positive attitude toward tourism development among a community in Bigodi, Uganda. Bigodi’s local community perception of tourism development suggests that tourism contributes to community development and agricultural markets, generates income, and ultimately brings prosperity.

Cengiz [71] investigated the attitudes of locals in the historical Turkish town of Amsra. The study explored the advantages and disadvantages of tourism development in the area. He found that tourism positively contributed to the town’s economic development. However, unplanned land development had a negative impact on its natural and traditional characteristics. Locals were aware of the town’s natural, historic, and cultural assets and believed that these assets should be preserved. As a result, it was advised that tourism development should be organized in accordance with the city’s carrying capacity to preserve the town’s natural, cultural, and historical characteristics.

In Malaysia, Marzuki [72] conducted a study to identify the impacts of tourism development on residents in Langkawi. Findings from a household survey showed that the residents had experienced both advantages and disadvantages of tourism development, with more of the former, especially from a socioeconomic perspective. Tourism development brought more economic benefits, including an increase in employment and business opportunities and improved local infrastructure. However, social and environmental costs were major concerns, as there was evidence of cultural deterioration and negative impacts on physical development. Nevertheless, most residents believed that tourism development had significantly improved their quality of life.

Khizindar [9] investigated the impact of tourism on Saudi Arabian residents’ quality of life. This study reviewed four main characteristics that determine the scope of tourism: economic, social, cultural, and environmental. The data were gathered through a survey of 775 residents in the Makkah region, which is a popular pilgrimage site for Muslims from all around the world. The findings revealed that tourism had a very direct impact on people’s quality of life.

3.3. Residents’ Support for Tourism Development

Previous research has considered residents’ support for tourism [61,68,73,74,75]. Businesses, governments, and policymakers must understand and consider the needs and desires of residents if they want to maintain their support for tourism development [74]. It is critical for planners and developers to recognize that tourism development has an impact on residents. It is difficult to build a sustainable tourism economy in a town whose members do not support the sector [74].

Yoon [75] posits that locals with indifferent attitudes toward tourism will support tourism-related policies and eventually participate in the tourism development process if they perceive benefits from tourism impacts. Furthermore, Del Chiappa et al. [76] studied the role of residents’ participation in tourism development and concluded that encouraging public engagement in tourism development is critical for promoting tourism. The modern approach to tourism has started to incorporate sustainability into tourism development. This modern approach suggests that residents should be included in the tourism planning process to attain sustainability in tourism development.

Residents’ support for tourism is examined in terms of their attitudes, including their support for existing or potential tourism development and particular tourism development projects [57,61]. Numerous studies have found that residents’ perceptions of the positive and negative impacts of tourism development influence their support for tourism [53,57,59].

3.4. Factors Influencing Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts

Numerous studies have examined the external variables that influence residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and the direct and indirect relationships between these variables and residents’ attitudes towards tourism development [39,54,60,77,78,79,80]. These variables include community attachment [28,39,81,82,83,84,85], residents’ knowledge of tourism development [14,27,31,60,86], community involvement [46,61,84,87,88,89,90,91], and community satisfaction with tourism in terms of quality of life [14,69,92,93,94,95].

3.4.1. Community Attachment

Sociologists have been deeply concerned about individuals’ feelings about their communities. Many studies have examined the relationship between people and their communities in many areas (e.g., environmental psychology, anthropology, natural resource management, geography, and urban planning). Communities’ attachment to their places has become an essential concept in the social sciences as researchers start to examine the consequences of urbanization on community sentiment, the severe impacts of a rapidly growing population, and the inclusions of community attachment for social and mental well-being. While the notion of community attachment has been widely used in different areas, it is barely well defined in the literature and is sometimes confused with other concepts [96]. Community attachment is an individual’s emotional or affective attachment to a community or an individual’s affective connection to community life [83].

Later, community attachment became a major factor in tourism studies, as it impacts support for tourism development. Tourism scholars have utilized it in tourism support models to explore its implications for community perceptions of tourism impacts and attitudes toward the tourism industry in general [28,84]. Concerns regarding whether tourism will benefit the local community are likely to be influenced by a stronger attachment to the community [39,81,84,85,97]. Harrill [24] suggests that the more attached residents are to their community, the more likely they are to perceive tourism impacts negatively, as tourism development could reduce the quality of life in their community.

Bajrami et al. [98] found that residents with a stronger attachment to their community are likely to have a heightened awareness of the impacts of tourism. Consequently, they will evaluate more thoroughly whether the development of tourism will yield advantages for their locality. Similarly, Gursoy et al. [39] discovered that residents on Australia’s Sunshine Coast who had a higher level of community attachment perceived greater negative socioeconomic impacts of tourism but supported mass tourism development in their community. Other research, including that by Choi and Murray [81], found that locals who had strong ties to their community were more positive about the outcomes of tourism, and they intended to support tourism. In addition, Nicholas et al. [84] found that community attachment had a favorable impact on locals’ willingness to support tourism development. However, Rasoolimanesh et al. [54] analyzed data from 410 questionnaires filled out by locals who lived near the George Town World Heritage Site in Malaysia. They attempted to find out how community factors affected people’s perceptions of and support for WHS conservation. They found that there was a positive and significant relationship between community attachment and the perceived cost of tourism. These contradictions suggest the need for more investigation. Based on the former discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed for the present research:

H1a:

Community attachment has a positive effect on the perceived benefits of tourism development.

H1b:

Community attachment has a negative effect on the perceived costs of tourism development.

3.4.2. Residents’ Knowledge of Tourism Development

Some researchers have pointed out that residents’ support for tourism is necessary, which only occurs if their level of understanding of the tourism development process is in line with that of other stakeholders [99,100]. In the context of tourism, knowledge about tourism refers to an individual’s understanding of tourism activities that impact the community [31]. Residents who are knowledgeable about tourism development are better able to perceive tourism-related costs and benefits and the government’s role in the tourism planning process [31]. Local communities with minimal awareness of tourism processes and a lack of understanding of the value of sustainable tourism, especially in locations where tourism is new to the community, can be a barrier to community participation [19]. Several authors have also stated that having little knowledge and awareness of tourism development can create issues, widen the knowledge gap between local communities and decision-makers [101], and create false expectations about the impacts of tourism development [102].

Furthermore, previous studies have focused on assessing locals’ understanding and attitudes in regions where tourism is already a significant part of the local economy [103]. Few studies have investigated residents’ awareness and understanding during the early phases of tourism development [104]. In this regard, Saarinen [100] argues that it is critical to first examine the level of local community awareness and knowledge by looking at how residents perceive tourism development in their region. Assessing the community awareness and knowledge of tourism will help with filling in the gaps in the community’s understanding of the concept [105], thereby ensuring meaningful community participation in tourism development [103].

Locals’ knowledge of tourism must be investigated thoroughly, particularly in developing countries where the degree of knowledge about tourism is lower than that in developed countries, and locals may have different perspectives on tourism development [106]. Residents who are familiar with tourism are more likely to understand and realize the benefits and costs associated with its development [27,107], which can either promote or discourage their support for and participation in tourism development [27,60,88]. Andereck et al. [27] argued that to gain residents’ support for tourism development, it is essential to enhance their knowledge and awareness of it. Residents who are knowledgeable about tourism are more likely to perceive its impacts favorably. However, Nunkoo [86] found a significant association between knowledge and the perceived negative impacts of tourism. Látková and Vogt [60] established that residents’ awareness of tourism was not a predictor of the perceived impacts of tourism development. These contradictions suggest the need for more investigation. Based on the former discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed for the present research:

H2a:

There is a positive relationship between community members’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived benefits of tourism development.

H2b:

There is a negative relationship between community members’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived costs of tourism development.

3.4.3. Community Involvement

Tourism development brings a variety of economic, sociocultural, and environmental changes to local communities, some of which are favorable while others are not [59]. Aref et al. [108] define a community as a group of individuals who live in the same geographical region and share certain common interests. Similarly, Scherl and Edwards [109] describe local communities as individuals who share a common identity and may engage in a variety of interconnected livelihoods. They also point out that local communities commonly have legal rights to their country’s natural resources, as well as a strong cultural, social, economic, and spiritual connection to the region.

Community involvement is a process in which residents of a community are given an opportunity to participate in decisions that affect their lives [110]. In the tourism field, community involvement refers to a group of people actively participating in activities such as decision making, planning, implementation, monitoring, evaluation, and problem solving, with a clear understanding that tourism activities are advantageous to those who engage in them [111]. The engagement of residents is critical to the tourism industry’s long-term viability in any region [39]. Local engagement has been viewed as a beneficial force for change and the support for a country’s development. Community involvement in the tourism development process helps to retain the local culture and customs, and it contributes to the preservation of the local community’s environment [108].

The goal of community engagement should be to facilitate better decision making and long-term growth and development through good communication between stakeholders. Understanding citizens’ perspectives can help policymakers create policies that minimize the negative effects of tourism development while maximizing its benefits. This results in community development and increased support for tourism, especially in developing nations where tourism is still in its infancy. However, a lack of community engagement in tourism decision making can result in tourism development failure [112].

Local participation in tourism development can help a tourism industry succeed in the long run, as tourism development is heavily reliant on the amount of acceptance and support from residents [112]. Tourism studies suggest that involving the local community in management and decision making can encourage them to recognize the importance of integrating tourism into the local economy [61,87,88].

Some researchers have investigated the effects of community involvement in planning for tourism development [46,84,90]. Most researchers agree that residents with positive perceptions of tourism development are interested in participating, and their involvement enhances their commitment to support tourism development in their community, and vice versa [61,88]. However, according to Nicholas et al.’s [84] study, the level of community involvement had no impact on the perceived benefit and support for tourism development. In contrast, Lee [46] found that local involvement significantly impacts perceived benefits but there is no link between community involvement and the perceived cost of tourism development [46]. Stevic et al. [113] emphasize that transparent and accountable management practices, involving resident participation, are essential for securing support from the local community for tourism development. In addition, community involvement has been demonstrated to positively impact the economic benefits of tourism development [89,91]. These contradictions suggest the need for more investigation. Based on the former discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed for the present research:

H3a:

Community involvement has a positive effect on the perceived benefits of tourism development.

H3b:

Community involvement has a negative effect on the perceived costs of tourism development.

3.4.4. Perceived Impacts, Satisfaction with Tourism, and Residents’ Support for Tourism

Satisfaction refers to the perceived divergence between prior expectations and the perceived performance after consumption; dissatisfaction arises when the performance is below the expectations [114]. The degree to which one perceives that an experience creates positive feelings is regarded as satisfaction [115]. A tourist’s perspective primarily defines satisfaction by their pre-travel expectations and post-travel experiences. The tourist is satisfied when his or her experiences match his or her expectations, resulting in emotions of fulfillment, and vice versa [116].

Many researchers have realized possible connections between residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and their satisfaction with various aspects of tourism development. Residents’ perceptions of tourism’s impacts are highly related to their satisfaction and support for tourism development [69,92,93,94,95]. Kaplanidou et al. [92] found that residents’ satisfaction with their quality of life was influenced by the perceived economic impact of hosting the World Cup, and their overall satisfaction with their quality of life was positively related to their support for the event among South African locals. Kim et al. [93] found that residents’ perceptions of tourism development and its impacts in 135 counties and cities in Virginia state influenced their satisfaction with life domains.

Ko and Stewart [94] concluded that the perceived benefits and costs of tourism had an impact on overall community satisfaction (e.g., public service satisfaction, citizen involvement, and social opportunities). Lin et al. [95] also discovered that life satisfaction is positively influenced by perceived social–cultural and economic gains from tourism development. According to Vargas-Sanchez et al. [69], perceived positive impacts of tourism positively influence overall community satisfaction (e.g., service provided by the government, environment satisfaction, recreation opportunities satisfaction, economic satisfaction, and community involvement), but they found an insignificant relationship between perceived cost and overall community satisfaction.

It is worth noting that most researchers attempted to focus only on overall community satisfaction caused by tourism development. For example, researchers have shed light on public service, education, environment satisfaction, recreation activities satisfaction, economic satisfaction, citizen involvement, and social opportunities [69,92,93,94,95]. Focusing on a few aspects of residents’ satisfaction directly related to tourism development may be a good option for preliminary studies [29]. However, in this study, satisfaction refers to satisfaction with current tourism development planning, satisfaction with tourism development, satisfaction with having tourists, and satisfaction with the current improvement in the community conditions caused by tourism development. Based on the former discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed for the present research:

H4:

There is a positive relationship between the perceived benefits of tourism and residents’ satisfaction with tourism development.

H5:

There is a negative relationship between the perceived costs of tourism and residents’ satisfaction with tourism development.

In addition, an individual’s behavioral intentions are the most important determinant of their actual behavior [117]. According to SET studies, the more positively residents perceive the various impacts of tourism, the more likely they are to show stronger support for tourism development. Conversely, residents are less inclined to support further development if tourism is perceived to have negative impacts (i.e., damaging the community’s economic, sociocultural, and environmental conditions) [39,46,118]. A significant number of studies on communities’ support for tourism development have shown that understanding residents’ support is critical for long-term tourism development success [39,54,77,79,80,119]. Andereck and Vogt [77] and Erul et al. [119] found that locals who have a positive attitude toward tourism are more inclined to support tourism and sustainable tourism development. Moreover, Ribeiro et al. [80] discovered a direct link between residents’ attitudes and their support for tourism development. Similarly, other researchers have found a direct correlation between residents’ attitudes and their support for tourism development, and they have stressed the necessity of integrating residents’ behavioral intentions to support tourism development [119,120,121]. Based on the former discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed for the present research:

H6:

There is a positive relationship between the perceived benefits of tourism and residents’ intentions to support tourism development.

H7:

There is a negative relationship between the perceived costs of tourism and residents’ intentions to support tourism development.

Moreover, several tourism scholars have considered positive and negative attitudes as solid indicators of support for tourism development [39,54,77,79,80]. However, a few researchers, such as Eslami et al. [120], Nunkoo and Ramkissoon [122], and Woo et al. [123], have found life satisfaction to be a good predictor of residents’ level of support for tourism development. Gursoy et al. [79] suggested that if residents are satisfied with their community conditions, they are more likely to support tourism development. Conversely, when locals become unsatisfied due to the negative impacts of tourism, it indirectly impacts the tourism development plan because residents’ overall satisfaction level can determine their support for tourism development. As a result, knowing how satisfied locals are with tourism development might be a preventive way to minimize potential negative consequences. Based on the former discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed for the present research:

H8:

There is a positive relationship between residents’ satisfaction with tourism and their support for tourism development.

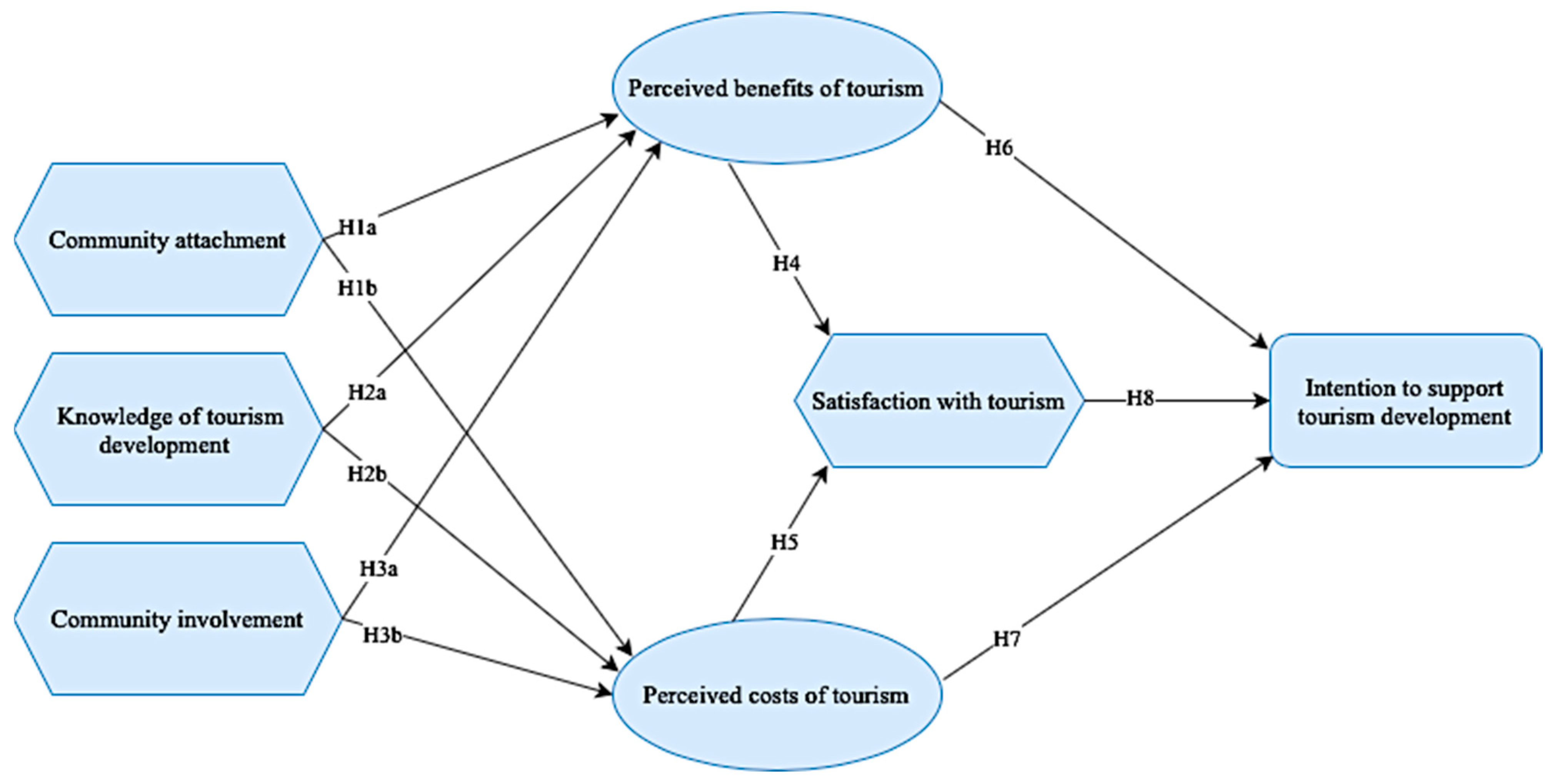

All the previously described hypotheses make up the framework of the present study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed framework of the current study.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample and Procedure

A convenience sampling method was used to best meet the purpose of the study. In terms of data collection, this study utilized a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed via a link created by the Qualtrics website to random people living in Riyadh city through emails and social networks. The study sample consisted of individuals aged 18 years or older residing in Saudi Arabia. To ensure the accuracy of the sample selection, filtering questions were implemented in the survey, such as “How long have you lived in Riyadh city?” Participants who did not reside in Riyadh or had lived there for less than five years were excluded from the final data analysis to ensure that the study’s objectives were met.

The preliminary version of the questionnaire was pilot tested with a group of residents in Riyadh. During the pilot testing, respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire and provide feedback on its suitability, noting any changes they deemed important. The researchers gathered additional comments to refine the questionnaire. A total of 50 complete responses were considered in the pilot study, and no major changes were required based on the feedback received.

4.2. Instrument Development

The questionnaire for this study included seven constructs. As indicated in Table 1, all the measurement items were derived from previously validated scales. To measure community attachment, five items were adopted from López et al. [124] and Adongo et al. [125]. Knowledge of tourism was measured using five items from Nunkoo [86] and Rasoolimanesh et al. [54]. Six items were used to measure community involvement, adopted from Moghavvemi et al. [30] and López et al. [124]. The perceived benefits of tourism development were measured using nine items from Teng [55], Látková and Vogt [60], and Gannon et al. [51]. The perceived costs of tourism development were measured using nine items from Teng [55] and Látková and Vogt [60]. Satisfaction with tourism development was measured using six items borrowed from Chow et al. [29] and Moghavvemi et al. [30]. Lastly, four items were used to measure the intention to support tourism development, borrowed from Nunkoo and Ramkissoon [122] and Látková and Vogt [60]. All items were measured by using a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Also, demographic information, such as gender, level of education, and income, was obtained.

Table 1.

Items included in the survey.

4.3. Data Analysis

In addition to descriptive statistics, which included correlation and reliability analysis, Mplus Version 8.6 was utilized to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). The study also assessed the reliability of the measurement items using Cronbach’s alpha, as well as evaluated the model fit and convergent and discriminant validity. The model’s reliability and validity were determined through factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). The measurement model was initially tested using CFA, which was followed by examining the structural equation to test the hypotheses.

5. Results

5.1. Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics

As shown in Table 2, of 428 respondents, 323 (75.5%) of them were male and 105 (24.5%) were female. According to the General Authority for Statistics in Saudi Arabia (2022), the demographic composition of the population is 61% male and 39% female. In this study’s sample, 75.5% of the respondents were male, and 24.5% were female. While the sample had a slightly higher proportion of males, it still aligns reasonably well with the population demographics, suggesting that our sample is broadly representative. In terms of age, almost half of the respondents (48.4%) were aged between 18 and 25 years old, 19.9% were aged between 26 and 34 years old, 25% were aged between 35 and 54 years old, 5.1% were aged between 55 and 64 years old, and 1.6% were aged 65 years or older. In terms of education level, almost half of the respondents (47.9%) had a bachelor’s degree, 0.7% had less than high school, 31.5% had a high school diploma or equivalent, and 19.9% had a graduate degree. Regarding the monthly income, most of the respondents (47.7%) monthly made about SAR 5000 or less, 9.8% of the respondents monthly made about SAR 5001–8000, 8.2% monthly made about SAR 8001–10,000, 6.3% monthly made about SAR 10,001–12,000, and 28% monthly made about SAR 12,000 and over. In terms of the duration of living in Riyadh city, most of the respondents (86.2%) had lived in Riyadh city over 11 years, 4.7% of the respondents had lived there between 1 and 5 years, and 9.1% of the sample had lived there between 6 and 10 years. In terms of traveling overseas, half of the respondents (55.5%) had traveled more than five times overseas, 16.4% indicated that they had never traveled, 18.5% had traveled between one and three times, and 9.6% had traveled between four and five times.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics (n = 428).

5.2. Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to check whether the measurement model was appropriate and adequate [126]. The measurement model’s validity was determined by its goodness of fit, which included the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and reliability of the constructs [127]. The initial goodness of fit of the measurement model was found to be acceptable (χ2 = 2747.963; df = 159; p < 0.001; TLI = 0.837; CFI = 0.848; SRMR = 0.066; RMSEA = 0.069). However, in this study, the ITS_1, ITS_2, Invol_1, Know_4, Pben_5, Pcos_5, Pcos_6, and Commu_4 items were deleted due to their poor factor loadings. After deleting these items, the re-specified model provided a better goodness of fit (χ2 = 1862.471; df = 135; p < 0.001; TLI = 0.856; CFI = 0.868; SRMR = 0.068; RMSEA = 0.070). Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study’s constructs. The variables presented in Table 3 were derived by calculating the mean of the measurement items associated with each variable.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix (n = 428).

5.3. Data Assumptions

To check the normality, Kline [128] recommended that the univariate skewness values be less than −3.0 or 3.0 and the kurtosis values be less than 10. In this study, the skewness scores ranged from −1.015 to 0.460, and the kurtosis values ranged from −0.415 to 1.250. Therefore, data normality in this study was achieved. The multicollinearity was checked by making sure that the variance inflation factors (VIFs) and tolerance values were within the indicated cutoff values (i.e., tolerance > 0.10; VIF: 10) [128]. The multicollinearity was checked by running numerous multiple regressions with each variable as a dependent variable and the other variables as independent variables. All tolerance values are greater than 0.728, and the VIF values are less than 1.737. The findings indicate that multicollinearity did not appear to be a significant concern in the current study.

In addition, the convergent and discriminant validities of the constructs were investigated. The convergent validity was assessed by using the standardized factor loadings of each indicator, the critical ratio (CR), and the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct (see Table 4). According to Hair et al. [126], standardized factor loadings should be statistically significant and at least 0.5, or higher than 0.7. In this study, all the standardized factor loadings were statistically significant at p < 0.001. The standardized loading estimates ranged between 0.503 and 0.916.

Table 4.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis, construct validity and reliability.

The AVE was calculated by the sum of the squared standardized factor loadings divided by the number of items under each construct. To ensure convergent validity, the AVE should be 0.5 or greater [126]. If the AVE is less than 0.5, it suggests more errors in the items than the variance explained by the construct [126]. The AVE values for all the latent constructs were above the minimum required value of 0.50 [129], except for the AVEs of the community attachment and perceived cost variables. However, Fornell and Larcker [127] claimed that if a construct has an AVE value lower than 0.5, but its CR value is higher than 0.6, as is the case of the community attachment and perceived cost constructs, its convergent validity is still appropriate. Therefore, the low AVEs of community attachment and perceived cost might be suitable in this study since they do not produce any major reliability or discriminant validity issues.

Moreover, the composite reliability was used as a measure of the constructs’ convergent validity. The composite reliability (CR) of each construct was calculated by the sum of the squared factor loadings divided by the total sum of the squared factor loadings and the sum of the error variance for the construct [126]. In this study, all the CR values ranged between 0.786 and 0.904. Thus, convergent validity was found to be desirable. This study used two forms of comparisons to determine the discriminant validity: (a) the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) versus the inter-factor correlations of any pair of constructs, and (b) the AVE versus the greatest shared squared value (MSV). The square root of the AVE for each construct is intended to be larger than any inter-factor correlations related to the construct [126].

5.4. Structural Model

The proposed research model was investigated using structural equation modeling (SEM) by checking the overall model fit and structural parameter estimates, including their size, direction, and statistical significance [126]. The goodness-of-fit statistics of the proposed model showed that the suggested model seems to reasonably fit the data (χ2 = 1936.562; df = 128; p < 0.001; TLI = 0.849; CFI = 0.860; SRMR = 0.084; RMSEA = 0.072).

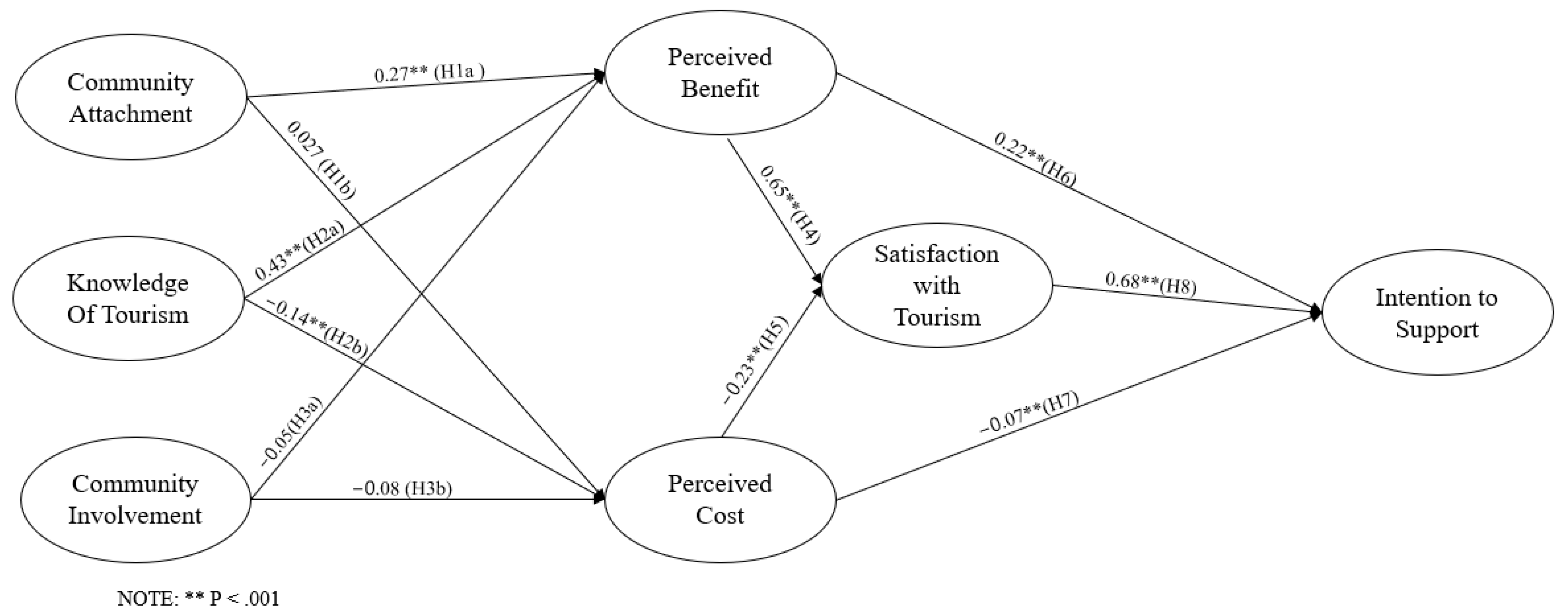

As shown in Table 5, the findings support H1a, which proposed a positive relationship between community attachment and the benefit perceived from tourism development (β = 0.279, p < 0.05). In contrast, the findings do not support H1b, which proposed a negative relationship between community attachment and the perceived cost from tourism development (β = 0.027, p > 0.05), so H1b was rejected. The findings of this study also support H2a and H2b, which proposed a relationship between residents’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived benefits and costs from tourism development. The results indicated that there is a significant positive relationship between residents’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived benefits from tourism development (β = 0.439, p < 0.05). In addition, the results provided a significant negative relationship between residents’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived costs from tourism development (β = −0.147, p < 0.05), so H2a and H2b are both supported.

Table 5.

Direct and indirect effects (n = 428).

The findings did not find support for the relationship between community involvement and its impacts on the perceived benefits and costs from tourism development. The relationship between community involvement and perceived benefits was negative and insignificant (β = −0.051, p > 0.05), and the relationship between community involvement and perceived costs was also negative and insignificant (β = −0.081, p > 0.05), so H3a and H3b were both rejected.

In addition, the findings provide support for the relationship between the effect of the perceived benefits and costs from tourism on satisfaction with tourism development. The results provide support for H4, which proposed a positive relationship between the perceived benefit of tourism development and community satisfaction with tourism (β = 0.654, p < 0.05), and for H4, which proposed a negative relationship between the perceived costs of tourism development and community satisfaction with tourism development (β = −0.232, p < 0.05), so H4 and H5 are both supported.

Moreover, the findings provide support for the relationship between the effect of the perceived benefits and costs from tourism on locals’ intentions to support tourism development. The findings provide support for H6, which proposed a positive relationship between the perceived benefits from tourism development and locals’ intentions to support tourism development (β = 0.229, p < 0.05). In addition, the findings provide support for H7, which proposed that a negative relationship exists between the perceived costs from tourism development and locals’ intentions to support tourism development (β = −0.072, p < 0.05). In addition, the findings provide support for H8, which proposed that a relationship exists between satisfaction with tourism and locals’ intentions to support tourism development (β = 0.686, p < 0.05).

6. Discussion

In this section, the following three main research questions are discussed:

RQ1.

How do external factors (e.g., community attachment, residents’ knowledge of tourism development, and community involvement) affect locals’ perceptions of tourism development and its impacts on Riyadh city?

The findings revealed a positive relationship between community attachment and the perceived benefit from tourism development (see Figure 2). This indicates that locals with strong community attachments are more likely to expect benefits from tourism development, which is inconsistent with the findings of some earlier studies. For example, a study conducted in New Braunfels, Texas, by Um and Crompton [85] showed that residents attached to their community perceived few positive impacts of tourism. Similarly, Gursoy et al. [39] discovered that residents of Australia’s Sunshine Coast with high levels of community attachments perceived tourism as having significant negative socioeconomic impacts, but they supported mass tourism development in their community. However, the present study’s results are consistent with the findings of Choi and Murray’s [81] study, which showed that locals who had strong ties to their community were optimistic about tourism outcomes and intended to support tourism. In addition, Nicholas et al. [84] found that community attachments had favorable impacts on locals’ willingness to support tourism development. No relationship between community attachment and the perceived costs of tourism development was found in the present study. This indicates that locals who are attached to their community do not necessarily expect any costs associated with tourism development, which is inconsistent with the findings of Rasoolimanesh et al. [54], which showed a positive and significant relationship between community attachment and the perceived costs of tourism.

Figure 2.

The results of the structural model.

Butler’s [130] Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model is a key instrument for assessing the development of a destination. The TALC model describes residents’ interactions with and reactions to tourists [130,131] based on the many stages of exploration that arise as a destination develops: involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, and, possibly, decline. Different elements influence each stage, such as the development rate, number of tourists, accessibility, and locals’ capacity for tourism [132].

During the exploration stage, residents share local amenities with tourists, but their active participation in providing services is rare. In addition, residents who have positive perceptions of the impacts of tourism tend to ignore all the tourism costs. As the number of visitors increases, more locals start offering facilities and services to tourists [133]. Thus, the destination enters the involvement stage, where visitor–host interaction remains strong. However, locals’ regular social routines (such as working hours and facility use) may change, especially during peak tourist seasons. The development phase starts as the popularity of the destination keeps rising. Overcrowding of tourists during peak periods may result in competition for public facilities. The subsequent consolidation phase reflects the local economy’s increased reliance on tourism. At this stage, the growth of the tourism industry may spark criticism and unhappiness among the locals, bringing them to the irritation stage, as it is described by Doxey [134] and his famous Irridex (Irritation Index). This irritation has currently evolved into the concept of tourismphobia [135].

When its peak tourist and local carrying capacities are met or exceeded, a destination may move into the stagnation stage, which is accompanied by an increase in environmental, social, and economic impacts. An oversupply of tourism-related supplies then prompts business closures and changes in property ownership. As a result, the destination begins to decay and loses its reputation. Locals need to prepare for potential changes and modify their lifestyles depending on whether the area is in a state of decline or regeneration [132].

Trentelman [136] suggests that any increase in population size and density due to tourism negatively impacts the behaviors of the local community, thereby affecting their emotional attachment to their area of origin. However, the present study’s results indicate that there is no relationship between community attachment and the perceived costs of tourism development. This is probably because tourism development in Riyadh is in its early stages, and the locals may not be experiencing any economic, social, or environmental negative changes due to tourism development that would affect their attachments to the community.

A significant positive relationship between residents’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived benefits of tourism development was found in this study. In addition, the results revealed a significant negative relationship between residents’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived costs of tourism development, indicating that locals who are knowledgeable about tourism development expect tourism development to have either positive or negative impacts. This is consistent with the findings of Nunkoo’s [86] study, which showed a significant association between knowledge and the perceived negative impacts of tourism, but it is inconsistent with Látková and Vogt’s [60] report that residents’ awareness of tourism is not a predictor of the perceived impacts of tourism development.

Local knowledge of tourism development is essential for a tourism development plan to be sustainable and run effectively [137]. In addition, locals’ knowledge about the government’s role in tourism development is an essential subject in the literature, and this knowledge can generate trust between the locals and the government of an area [138]. When the locals know how the government performs, they can determine, with some degree of confidence, whether something is trustworthy, whereas ignorance breeds mistrust [139,140]. A lack of information may also lead to bias against and, thus, reduced confidence in the government among local communities [86]. In the context of this study, knowledge encompasses the role of the government in spreading awareness among local communities about current tourism plans, the extent to which local communities are aware of ongoing tourism development measures in the city of Riyadh, and the local communities’ understanding of tourism development and its potential impacts.

The Vision 2030 program includes the use of best practices to achieve the highest level of transparency and good governance in all sectors. The Saudi government works toward achieving these high standards of transparency by announcing their goals and plans, measuring the performance and the extent of success achieved, and making information available to all. Furthermore, the government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia provides statements of progress and continuity without any ambiguity, revealing any defects, transgressions, and misuses of power. This enables decisions to be taken to achieve goals that enhance the value of loyalty and belonging, as well as pride in the government and state leadership.

As transparency has become an essential framework within Vision 2030 to combat corruption in all its forms, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has made evident strides toward following the principles of transparency and clarity in all government dealings. Vision 2030 was developed following a realization of the seriousness of corruption, and governance, transparency, integrity, and combating corruption are among its main pillars. The results of the present study indicate that the local community is generally knowledgeable about the tourism development initiatives in Riyadh city. This awareness is attributed to the Saudi government’s practice of sharing its goals and achievements with complete transparency. The principle of transparency pursued by the Saudi government—which involves explaining to the local community all developments made in accordance with the goals of Vision 2030—has played a fundamental role in increasing the local community’s knowledge about tourism development in Riyadh city.

An insignificant relationship between community involvement and the perceived benefits and costs of tourism development was found. This may be because community participation in decision making for tourism development does not necessarily affect community members’ perceptions of the benefits and costs of tourism development. This result is consistent with previous findings. Nicholas et al. [84] reported, for example, that the level of community involvement has no impact on the perceived benefits of and support for tourism development. In addition, Lee [46] found no link between community involvement and the perceived costs of tourism development. However, this result is inconsistent with Lee’s [46] study, which showed that community involvement significantly impacts perceived benefits.

It is well accepted that developing a destination is a challenging process for any agency, and that it is impossible without the active involvement of local communities, especially if that development wants to be sustainable [141]. Local communities constitute a crucial element of a destination, and their contributions to its growth cannot be underestimated. Locals contribute significantly to promoting tourism because they are far more familiar with the area’s tourist attractions than outsiders are. To obtain the best support from host communities, it is crucial to involve them in developing tourism in favorable ways [142]. According to Murphy [143], limited delays and balanced development are only achievable if more locals get involved in the initial stages of tourism development. Snyman [144] favors community-driven tourism, in which locals are in charge of managing the services and infrastructure that are already in place. Since local communities experience the positive as well as negative effects of tourism, directly or indirectly, their involvement is crucial to better managing these effects and maximizing them [145].

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model suggests that tourism becomes increasingly critical for job creation and economic expansion during the early stages of development. The TALC model also indicates that locals ignore all tourism costs in the early stages of tourism growth because they have positive perceptions of tourism and its benefits [130]. At this point, local government officials and business owners aggressively promote tourism around the community. Business owners and tourism professionals recognize the need to win over the community’s support. They recommend that efforts be made to increase locals’ awareness of the advantages of tourism development for the entire community.

Locals may also consider tourism a potential development source, thus perceiving the costs and obstacles to daily living as acceptable and justifiable [146]. The present study’s results indicate that no relationship exists between community involvement and the perceived impacts of tourism. With no significant impacts resulting from tourism development—because many projects that have been announced have yet to finish their development processes—the local community’s reluctance to participate in decision making is justifiable;

RQ2.

How do the perceived impacts of tourism development affect locals’ intentions to support tourism development in Riyadh city?

A positive relationship between the perceived benefits of tourism development and locals’ intentions to support tourism development and a negative relationship between the perceived costs of tourism development and locals’ intentions to support tourism development were found. This indicates that the support of local communities depends on the perceived benefits and costs of tourism development. Andereck and Vogt [77] reported that locals with positive attitudes toward tourism are more inclined to support sustainable tourism development. Moreover, Ribeiro et al. [80] discovered a direct link between residents’ attitudes and their support for tourism development. Similarly, other researchers have found a direct correlation between residents’ attitudes and their support for tourism development [119,120,121].

The results of this study support social exchange theory, which posits that residents’ attitudes toward tourism development are influenced by their perceptions of the benefits and costs associated with tourism. Most of Riyadh’s citizens were found to eagerly support the expansion of the tourism industry because of the perceived benefits of tourism activities, which span sociocultural, environmental, and economic aspects. The respondents conveyed their strong desire for additional tourism development in the area and stated that tourism authorities should work to increase tourist numbers. Most locals believed that the region’s best chance of economic growth is through tourism. Overall, it is clear from the findings that the local population is quite supportive of tourism development and are committed to providing ongoing assistance with the construction of local tourism facilities and infrastructure. In addition, the residents are aware of the government’s effort to promote tourism for the benefit of Riyadh city;

RQ3.

How do the perceived impacts of tourism development affect locals’ satisfaction with tourism and their intentions to support tourism development in Riyadh city?

A positive relationship between the perceived benefits of tourism development and community satisfaction with tourism and a negative relationship between the perceived costs of tourism development and community satisfaction with tourism development were found in this study. In addition, a relationship between satisfaction with tourism and locals’ intentions to support tourism development was observed. Thus, locals’ expectations of benefits from tourism development reflect their satisfaction with tourism development, and vice versa. Moreover, the results indicate that locals who are satisfied with the tourism initiatives in their area will support tourism development. This is consistent with the findings of Kaplanidou et al.’s [92] study, in which South African residents’ satisfaction with their quality of life was influenced by the perceived economic impacts, and their overall satisfaction with quality of life was positively related to their support for hosting the World Cup.

Kim et al. [93] found that residents’ perceptions of tourism development and its impacts in 135 counties and cities in Virginia influenced their satisfaction with various life domains. Moreover, Ko and Stewart [94] concluded that the perceived benefits and costs of tourism have impacts on overall community satisfaction (e.g., public service satisfaction, citizen involvement, and social opportunities). Lin et al. [95] stated that life satisfaction is positively influenced by the perceived sociocultural and economic gains from tourism development. Further, Vargas-Sanchez et al. [69] reported that tourism positively influences overall community satisfaction (e.g., governmental services, environment satisfaction, recreational opportunities, economic satisfaction, and community involvement), while an insignificant relationship exists between perceived costs and overall community satisfaction.

Eslami et al. [120], Nunkoo and Ramkissoon [122], and Woo et al. [123] found life satisfaction to be a good predictor of residents’ level of support for tourism development. According to Gursoy et al. [79], if residents are satisfied with the conditions of their community, they will support tourism development. Conversely, locals’ dissatisfaction due to the negative impacts of tourism indirectly impacts the tourism development plan for the area because the residents’ overall satisfaction level determines their support for tourism development.

Tourism development in the city of Riyadh is in its initial stages, so the local community is satisfied with the current tourism development approach and is also willing to support it. However, the well-being of residents who reside in tourist and non-tourist areas and the economic, social, cultural, and environmental aspects of residents’ lives may be impacted, both positively and negatively, by tourism and tourist inflows [147].

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model suggests that in the early phases, an increase in tourist arrivals is expected to bring significant benefits, such as the creation of new jobs and the opening of new recreational facilities. In this stage, tourist inflows are not high enough to drive up prices, destroy the identity of a community, or cause environmental damage. As the area becomes more well known as a tourist destination and the number of tourists increases, the potential for economic and social improvements for residents decreases (i.e., prices rise and homelessness, traffic, pollution, noise, and crime increase), and locals may feel as though their community is losing its identity.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Implications

Since introducing Saudi Vision 2030, the Saudi government has promised to carry out its national reform plan. In order to survive the post-oil period, economic diversification is seen as one of the keys. Development of the tourism industry has costs as well as benefits. These tourism-related projects will have an impact on locals’ lives once a destination becomes a tourist destination. The residents’ values, actions, lifestyles, and even the quality of their lives alter as a result of these consequences. The main goal of this study is to assess how Saudi Arabia’s host communities perceive tourism’s economic impacts, sociocultural issues, and environment in relation to their support for tourism development.

An in-depth review of journal databases and the academic literature carried out within the framework of this research has revealed that there are very limited studies with a theoretical base that measure the perceptions of Saudi citizens in Riyadh city about the perceived impacts of tourism development and the intention to support tourism development. In addition, there is no study that examines how such factors (e.g., community attachment, resident’s knowledge of tourism development, and community involvement) could influence Saudi locals’ perceptions of tourism development and its impacts, or how the perceived impacts of tourism affect locals’ satisfaction and support for tourism development, and, in turn, how locals’ satisfaction with tourism affects their intention to support tourism development in Riyadh city.

This research investigated how residents of Riyadh city perceive and support tourism development. Eleven hypotheses were proposed, out of which eight were confirmed. Utilizing social exchange theory (SET), the study explored Saudi residents’ perceptions of tourism development impacts from a costs-and-benefits standpoint. Additionally, the research analyzed the relationship between residents’ support for tourism and various factors, including both positive and negative impacts of tourism, community attachment, knowledge of tourism development, community involvement, and satisfaction with tourism development. Overall, the findings revealed that Saudi locals are more inclined to support tourism if they perceive its impacts as beneficial.

Gursoy and Rutherford [57] assert that for tourism development to be successful, community leaders, tourism developers, local planners, and policymakers must all take local perceptions into account. The Saudi government can use this study’s results to better understand the variables that affect how locals perceive and support tourism development. Additionally, because this study focused on Saudi Arabia, its findings can be compared with those of earlier studies carried out in other countries, advancing knowledge of locals’ perceptions of tourism development.

This study found that perceived positive impacts of tourism encourage residents to support it, while perceived negative impacts make residents less supportive of tourism development. This finding suggests that, to gain more resident support for tourism development, the Saudi government should focus on translating the impacts of tourism into actual perceived positive impacts for residents. In other words, even if there are positive impacts of tourism, residents need to perceive these impacts positively because such perceptions lead to their support for tourism development. Therefore, to secure active support from residents, the Saudi government needs to enhance residents’ awareness of tourism’s benefits sufficiently. Simultaneously, this study indicates that the Saudi government should also work on minimizing the perceived negative impacts.

This study finds that residents who perceive tourism to have favorable impacts are more likely to support it, whereas those who see tourism as having adverse impacts are less likely to do so. Based on these findings, the Saudi Arabian government should consider how to translate the benefits of tourism into tangible outcomes to gain more support for the development of the tourism industry. Additionally, this study suggests that Saudi Arabia’s government should take steps to lessen any perceived environmental, sociocultural, and economic impacts of tourism.

Also, the findings demonstrate that strong community attachment positively affects perceived positive impacts of tourism but does not affect the negative impacts of tourism. Saudi residents who are attached to their community tend to perceive tourism positively. This finding suggests that even when there are negative impacts of tourism, locals who are attached to their community do not take these impacts critically and instead concentrate on the positive impacts. Therefore, it may be assumed that the Saudi government may need to engage in more communication with locals to outline the advantages that tourism might bring to their community. The tension between those who believe that tourism development has adverse impacts on their society and others who believe that tourism can have more positive impacts can be reduced if locals can see how tourism can benefit their community.

This study found a significant positive relationship between residents’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived benefits of tourism development, and a negative relationship between residents’ knowledge of tourism and the perceived costs of tourism development, indicating that locals who are knowledgeable about tourism development expect it to have either positive or negative impacts. The Saudi government must pay greater attention to campaigns that promote tourism. These campaigns will raise locals’ awareness of the advantages and disadvantages of tourism. Locals will be more receptive to tourism development if they have a better understanding of the industry. Therefore, residents’ degree of knowledge needs to be taken into consideration because it can address their various attitudes and influence how they see tourism in the future. The government is urged to offer financial assistance for implementing awareness campaigns.

Moreover, it has been shown that community involvement has no significant impact on the perceived positive and negative impacts of tourism. Therefore, the Saudi government should implement a participative strategy by giving locals more of a role in decision making. Public engagement could be improved by informing people about the advantages of tourism development and establishing tourism advisory committees where locals’ concerns are considered. Therefore, there should be more interaction between tourism officials and locals, allowing the former to learn about locals’ concerns and interests. Such programs should also be developed to boost the locals’ level of activity participation. For instance, the Saudi government could give locals the chance to engage in tourism-related activities and contribute to the success of community-based tourism. Additionally, the Saudi government should give locals the chance to participate in the management and planning of the local tourism industry.

In addition, a positive relationship between the perceived benefits of tourism development and community satisfaction with tourism and a negative relationship between the perceived costs of tourism development and community satisfaction with tourism development were found in this study. Moreover, the results indicate that locals who are satisfied with the tourism initiatives in their area will support tourism development. These results imply that tourism planners should take the impacts of tourism development into consideration. Therefore, they should focus their efforts on raising locals’ satisfaction with the social, economic, and environmental aspects of tourism development. Policies may be aimed at reducing crime and other issues associated with tourism, such as traffic congestion and environmental degradation, enhancing the area’s surroundings, and providing recreational and entertainment facilities, all of which will improve the public safety. On their part, policymakers should ensure that the region’s infrastructure, institutions, and services are all developed in a way that supports the development of tourism.

Although the results of this study are highly specific to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, the findings have broader applicability that can be extrapolated to other emerging tourism destinations globally. The insights gained from examining the interplay between community attachment, residents’ knowledge of tourism, community involvement, and the perceived benefits and costs of tourism development are universally relevant. By emphasizing the role of social exchange theory in understanding local perceptions, this research provides a valuable framework for other destinations seeking to balance tourism growth with community satisfaction. Consequently, this study contributes to a global context by offering practical and theoretical implications that can inform sustainable tourism planning and development strategies in diverse settings worldwide.

7.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This research has certain limitations that present opportunities for further investigation. Firstly, the findings from this study may not be applicable to residents’ perceptions in other destinations, as these locations may differ in characteristics such as their types of tourism, cultural settings, geophysical features, and levels of tourism development. Future studies should focus on validating the model in other regions, considering that tourist destinations vary in their attributes and extents of tourism development, and its impacts. Secondly, the study focused on quantitative research; therefore, more thorough analysis for future studies should be considered by using qualitative analysis to gain a deeper understanding of the residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards tourism development. Thirdly, the present study just focused on some selected observed indicators, variables, and constructs. Although these constructs are based on the literature or researcher’s observations, other important constructs or variables may exist in future studies which could affect residents’ support for tourism development. Fourthly, this study examined only residents’ reactions toward tourism. There are other stakeholders besides residents in tourism development, such as tourists, tourism organizations, travel agencies, and governments. Future studies should focus on tourism service providers, local bodies, and tourists’ perceptions in such a way that sustainable tourism development can be achieved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and F.R.; Methodology, M.A. and F.R.; Validation, F.R.; Formal analysis, M.A. and S.A.; Investigation, M.A.; Data curation, M.A. and S.A.; Writing—original draft, M.A.; Writing—review & editing, F.R. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by King Saud University (fund number RSPD2024R542).

Institutional Review Board Statement