Primary Care Clinical Practice Guidelines and Referral Pathways for Oral and Dental Diseases in Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Background

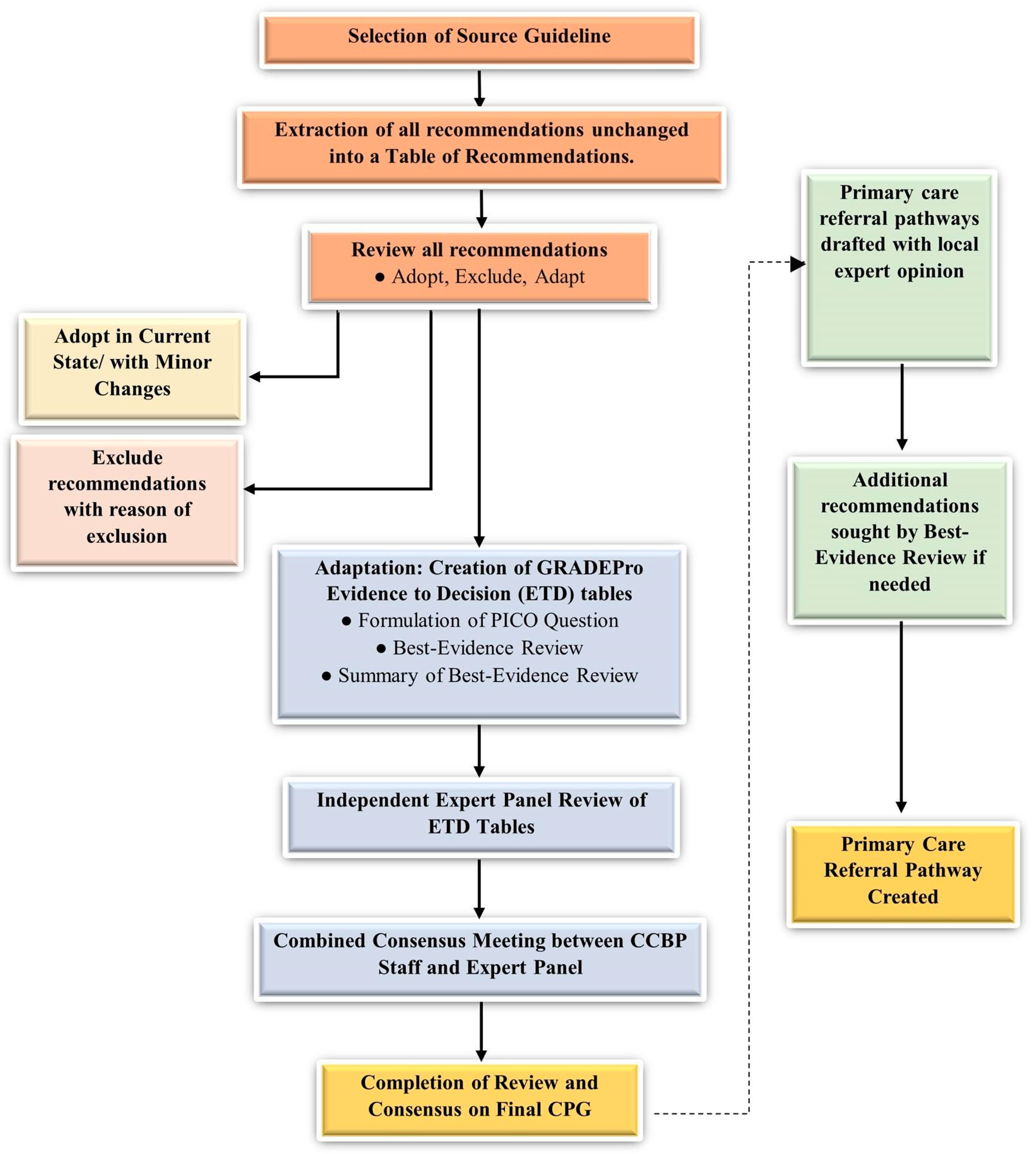

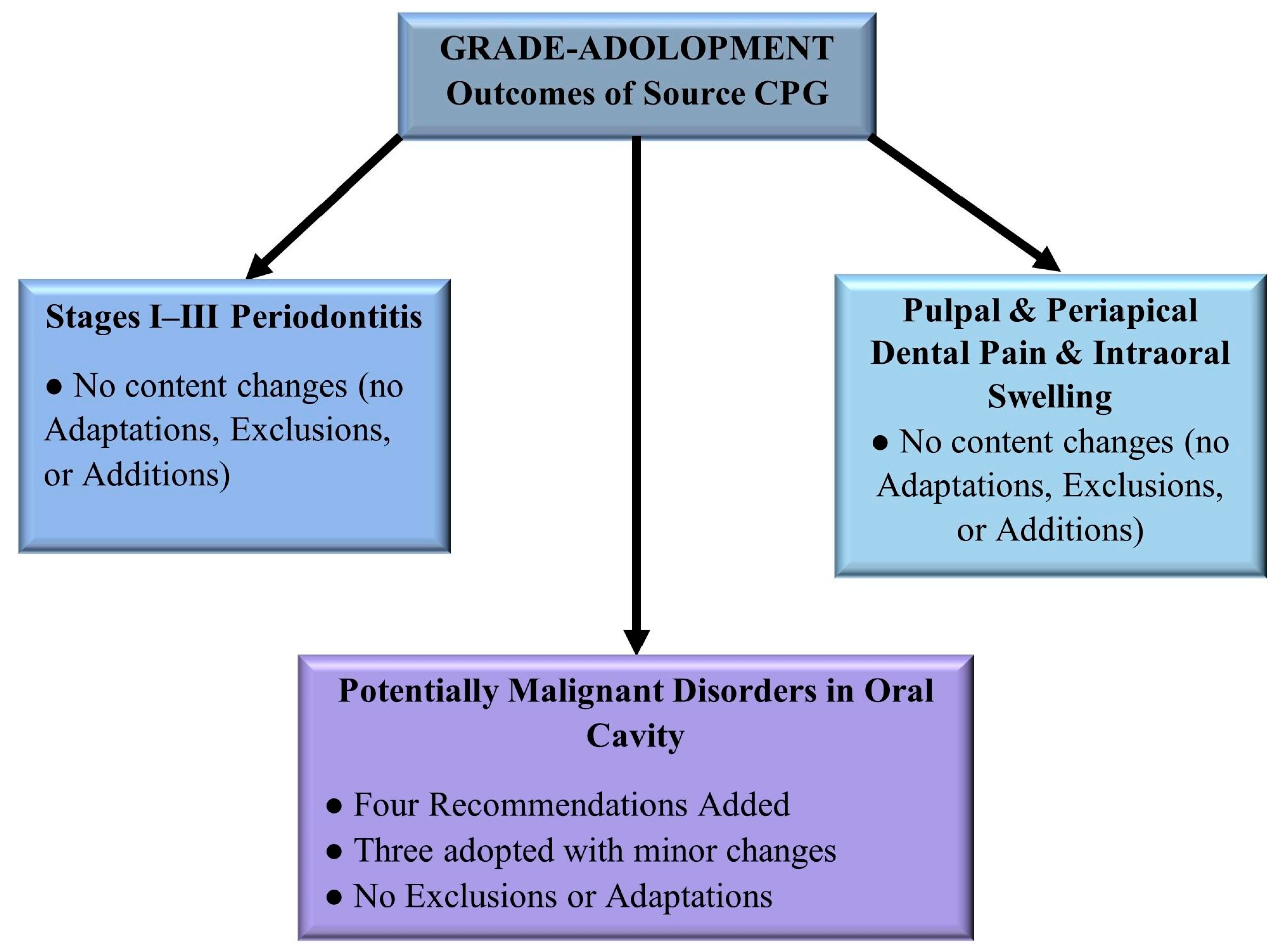

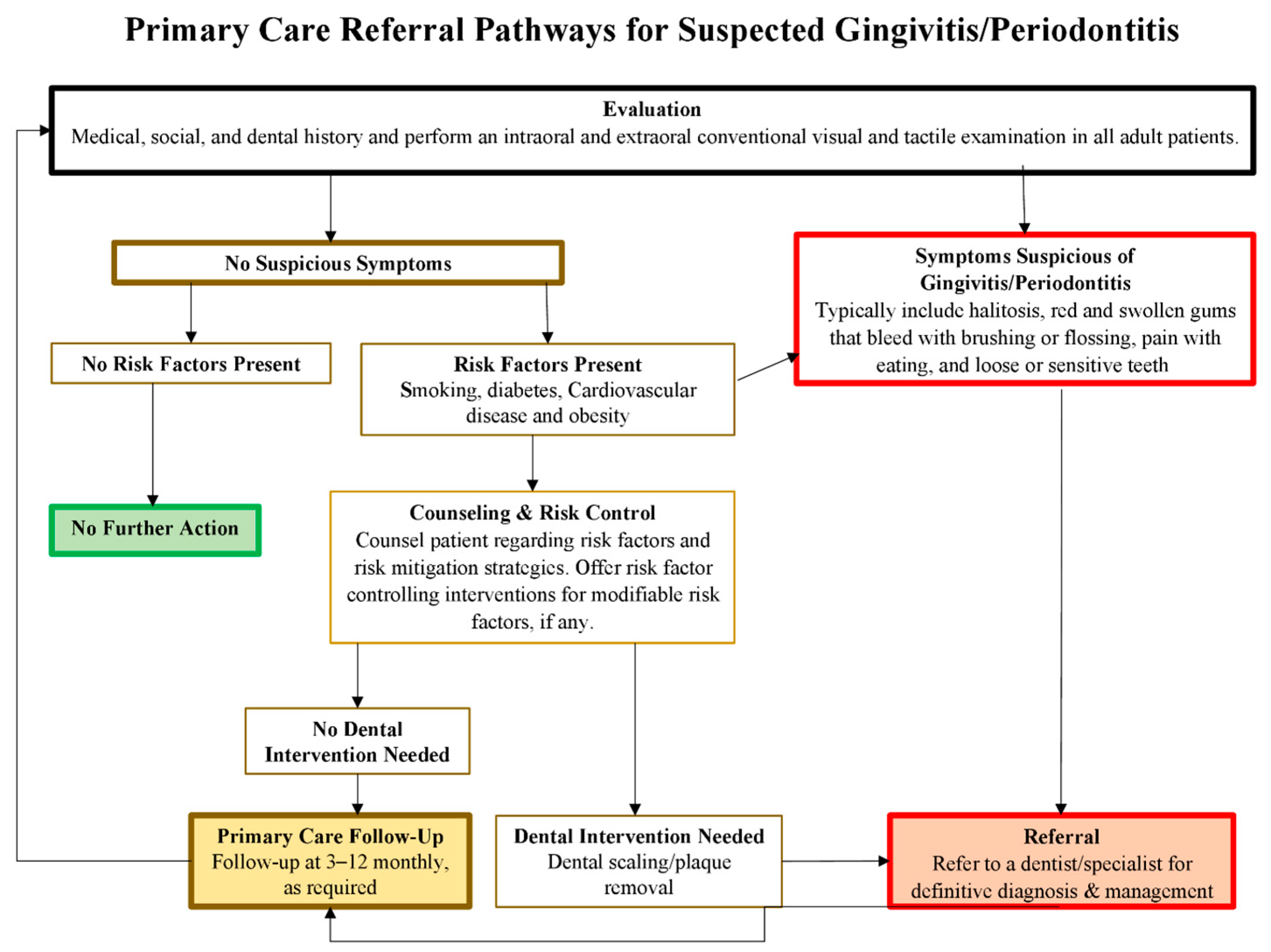

2. Methods

3. Results

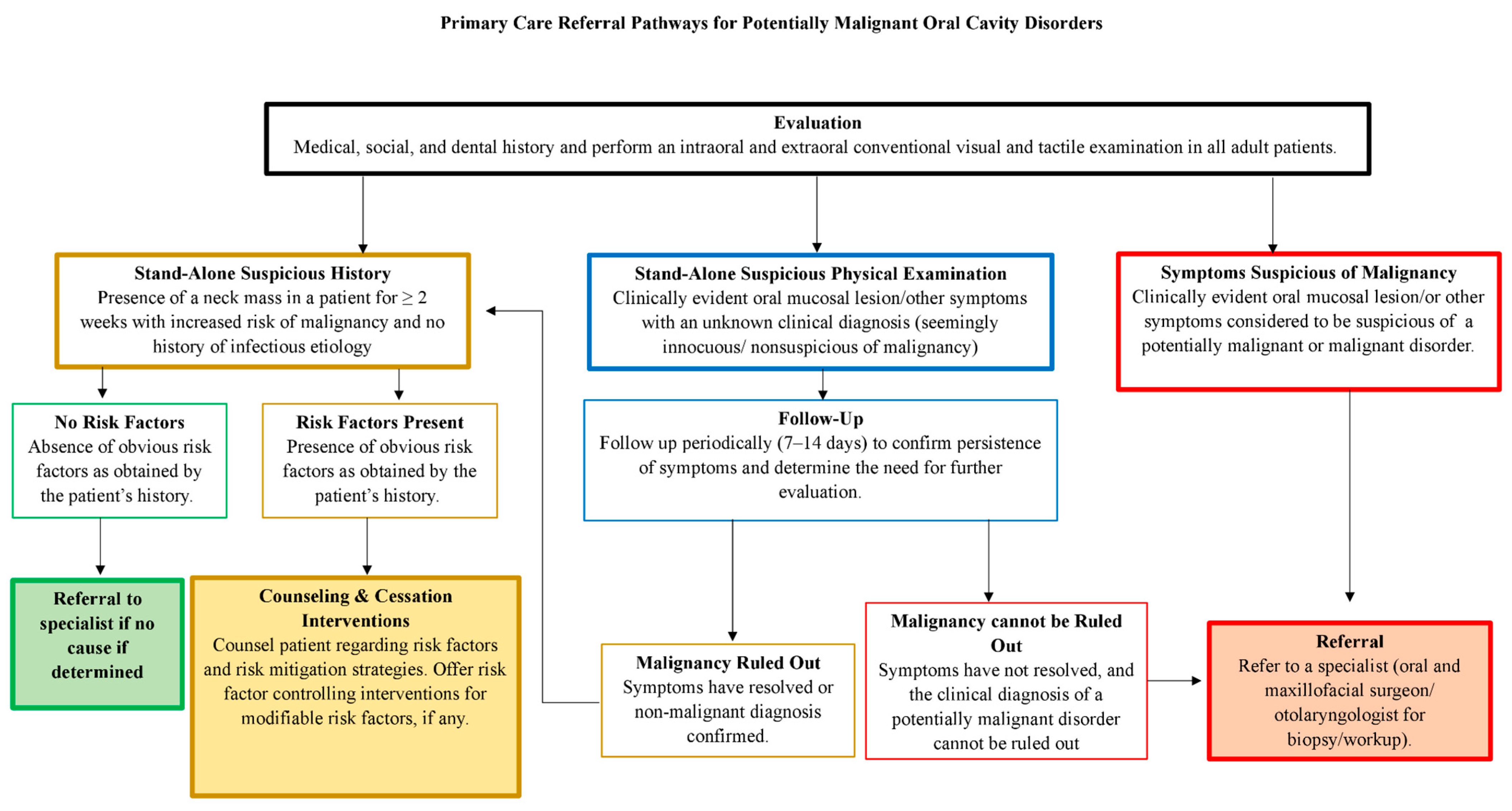

3.1. Follow-Up and Referral for Potentially Malignant Lesions

3.2. Biopsy and Referral for Suspicious Lesions

3.3. No Action for Patients without Lesions, Symptoms, or Risk Factors

- Risk Factor Mitigation for Asymptomatic Patients:

- 2.

- Tobacco Cessation Counseling:

- 3.

- Behavioral Interventions and Pharmacotherapy for Tobacco Cessation:

- 4.

- Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure Counseling:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKU | Aga Khan University |

| CCBP | Center for Clinical Best Practices |

| CITRIC | Clinical and Translational Research Incubator |

| CPGs | Clinical practice guidelines |

| DOMS | Dental, Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery |

| EtD | Evidence to decision table |

| FGD | Focus group discussion |

| GP | General physician |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| LMIC | Lower-middle-income country |

| PDA | Pakistan Dental Association |

| ToR | Table of recommendations |

References

- WHO. Oral Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Bernabe, E.; Marcenes, W.; Hernandez, C.R.; Bailey, J.; Abreu, L.G.; Alipour, V.; Amini, S.; Arabloo, J.; Arefi, Z.; GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators; et al. Global, Regional, and National Levels and Trends in Burden of Oral Conditions from 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, A.A.; Alshammary, F.; Mulla, M.; Al-Zubaidi, S.M.; Afroze, E.; Amin, J.; Amin, S.; Shaikh, S.; Madfa, A.A.; Alam, M.K. Prevalence of dental caries in Pakistan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F.; Bsc, M.F.B.; Me, J.F.; Soerjomataram, M.I.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righolt, A.; Jevdjevic, M.; Marcenes, W.; Listl, S. Global-, regional-, and country-level economic impacts of dental diseases in 2015. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gift, H.C.; Atchison, K.A. Oral health, health, and health-related quality of life. Med. Care 1995, 33, NS57–NS77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisely, S. No Mental Health without Oral Health. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2016, 61, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ADA. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Dental Evidence. 2022. Available online: https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/evidence-based-dental-research (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- (NICE) NIfHaCE. Oral and Dental Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/oral-and-dental-health (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- (RCS) RCoSoE. Clinical Guidelines. 2022. Available online: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/dental-faculties/fds/publications-guidelines/clinical-guidelines/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Kravitz, A.; Bullock, A.; Cowpe, J.; Barnes, E. EU Manual of Dental Practice 2015; The Council of European Dentists: Cardiffy, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Gupta, B.M. Mapping of dental science research in India: A scientometric analysis of India’s research output, 1999–2008. Scientometrics 2010, 85, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Wiercioch, W.; Brozek, J.; Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, I.; Mustafa, R.A.; Manja, V.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Falavigna, M.; Falavigna, M.; et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 81, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niaz, M.O.; Naseem, M.; Siddiqui, S.N.; Khurshid, Z. An outline of the oral health challenges in “Pakistani” population and a discussion of approaches to these challenges. JPDA 2013, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Basharat, S.; Shaikh, B.T. Primary oral health care: A missing link in public health in Pakistan. East. Mediterr. Health J. La Rev. Sante La Mediterr. Orient.=Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit 2016, 22, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, K.; Maqbool, F.; Khan, F.; Bahadar, H.; Ismail Hassan, F.; Abdollahi, M. Smokeless tobacco (paan and gutkha) consumption, prevalence, and contribution to oral cancer. Epidemiol. Health 2017, 39, e2017009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Dawani, N.; Bilal, S. Perceptions and myths regarding oral health care amongst strata of low socio economic community in Karachi, Pakistan. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2012, 62, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hussain, P.; Anjum, Q.; Iqbal, Z. Oral Hygiene Awareness among the Patients visiting the Dental Centers of a Rural Area of the Province Punjab, Pakistan. Biomedica 2017, 33, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Basharat, S.; Shaikh, B.T.; Rashid, H.U.; Rashid, M. Health seeking behaviour, delayed presentation and its impact among oral cancer patients in Pakistan: A retrospective qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 715. [Google Scholar]

- Qadir, S.A.; Shahzad, M.; Yousafzai, Y.M. Assessment of oral health related knowledge, attitude, and self-reported practices of families residing in Peshawar, Pakistan. Adv. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 3, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabé, E.; Masood, M.; Vujicic, M. The impact of out-of-pocket payments for dental care on household finances in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugwell, P.; Knottnerus, J.A. Adolopment—A new term added to the Clinical Epidemiology Lexicon. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 81, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.C.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Pottie, K.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Coello, P.A.; Rind, D.; Montori, V.M.; Brito, J.P.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—Determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 66, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Coello, P.; Oxman, A.D.; Moberg, J.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Akl, E.A.; Davoli, M.; Treweek, S.; Mustafa, R.A.; Vandvik, P.O.; Meerpohl, J.; et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: A systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016, 353, i2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J.; Moberg, J.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Akl, E.A.; Davoli, M.; Treweek, S.; Mustafa, R.A.; Vandvik, P.O.; Meerpohl, J.; et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: A systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ 2016, 353, i2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaidi, I. Ratio of dental surgeon versus population in Pakistan deplorable: PM’s aide. Dawn, 2 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A. Dentistry in Pakistan-Standing at the Crossroads Facing Numerous Challenges with an Uncertain Future. J. Pak. Dent. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Jawaid, S.A. Plight of Dentistry in Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglass, A.B.; Maier, R. Promoting Oral Health: The Family Physicians’ Role. Am. Fam. Physician 2008, 78, 814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- (JPDA) JotPDA. About Pakistan Dental Association (PDA). 2016. Available online: https://archive.jpda.com.pk/about-us/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Ali Shah, S.M.; Saquib, K.M.; Omer, S.A.; Mirza, D.; Ali, A. Awareness, knowledge & practice of evidence-based dentistry amongest dentists in Karachi. Pak. Oral Dent. J. 2015, 35, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, I.U.; Rehman, Z.U. Medical Research in Pakistan; A Bibliometric Evaluation from 2001 to 2020. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, M.; Herrera, D.; Kebschull, M.; Chapple, I.; Jepsen, S.; Berglundh, T.; Sculean, A.; Tonetti, M.S.; On behalf of the EFP Workshop Participants and Methodological Consultants. Treatment of stage I–III periodontitis—The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 4–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart, P.B.; Tampi, M.P.; Abt, E.; Aminoshariae, A.; Durkin, M.J.; Fouad, A.F.; Gopal, P.; Hatten, B.W.; Kennedy, E.; Lang, M.S.; et al. Evidence- based clinical practice guideline on antibiotic use for the urgent management of pulpal-and periapical-related dental pain and intraoral swelling: A report from the American Dental Association. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 906–921.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingen, M.W.; Abt, E.; Agrawal, N.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Cohen, E.; D’Souza, G.; Gurenlian, J.; Kalmar, J.R.; Kerr, A.R.; Lambert, P.M.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders in the oral cavity: A report of the American Dental Association. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2017, 148, 712–727.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.S.; Masood, M.Q.; Mahmud, O.; Rizvi, N.A.; Sheikh, A.; Islam, N.; Khowaja, A.N.A.; Ram, N.; Furqan, S.; Mustafa, M.A.; et al. Adolopment of adult diabetes mellitus management guidelines for a Pakistani context: Methodology and challenges. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1081361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqib, M.A.N.; Rafique, I.; Qureshi, H.; Munir, M.A.; Bashir, R.; Arif, B.W.; Bhatti, K.; Ahmed, S.A.K.; Bhatti, L. Burden of tobacco in Pakistan: Findings from global adult tobacco survey 2014. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musaddique Hussain, A.M.; Imran, I.; Rasool, M.F.; Hussain, I.; Barkat, Q.; Wu, X. Pakistan: Time for Stronger Enforcement on Tobacco Control. BMJ. Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/tc/2019/12/12/pakistan-time-for-stronger-enforcement-on-tobacco-control/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- de Camargo Cancela, M.; Voti, L.; Guerra-Yi, M.; Chapuis, F.; Mazuir, M.; Curado, M.P. Oral cavity cancer in developed and in developing countries: Population-based incidence. Head Neck 2010, 32, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, S.J.; Pasha, A.; Pasha, H.; John, R.; Jha, P.; Baloch, A.; Kamboh, G.N.; Cherukupalli, R.; Chaloupka, F.J. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Taxation in Pakistan; International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, M.; Haque, A.S.; Awan, S.; Khan, J.A. Reasons of failure to quit smoking: A cross sectional survey in major cities of Pakistan. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44 (Suppl. S58), 4466. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, K.; Oyebode, O.; Masud, H. Experiences of young smokers in quitting smoking in twin cities of Pakistan: A phenomenological study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.S.; Junaid, M.U.; Khan, M.S.; Aziz, N.; Fazal, Z.Z.; Umoodi, M.; Shah, F.; Khan, J.A. Factors motivating smoking cessation: A cross-sectional study in a lower-middle-income country. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, P. The growing problem of alcoholism in Pakistan: An overview of current situation and treatment options. Int. J. Endors. Health Sci. Res. 2015, 3, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.; Dingle, J.J. Prevention of tobacco-caused disease. Can. Task Force Period. Health Exam. 1994, 500–511. Available online: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/1994-red-brick-en.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Tobacco: Preventing Uptake, Promoting Quitting and Treating Dependence; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- USPSTF. Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: Interventions; USPSTF: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Russell, M.A.; Merriman, R.; Stapleton, J.; Taylor, W. Effect of nicotine chewing gum as an adjunct to general practitioner’s advice against smoking. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1983, 287, 1782–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq Ahmed, S.H. Oral Health Care Systems Analysis in Pakistan: The Challenges Based on the WHO Building Blocks Framework and the Way Forward. Pak. J. Public Health 2015, 5, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Atchison, K.A.; Rozier, R.G.; Weintraub, J.A. Integration of Oral Health and Primary Care: Communication, Coordination and Referral. NAM Perspect. Available online: https://nam.edu/integration-of-oral-health-and-primary-care-communication-coordination-and-referral/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Guan, G.; Lau, J.; Yew, V.; U, J.; Qu, W.; Lam, J.; Polonowita, A.; Mei, L. Referrals by general dental practitioners and medical practitioners to oral medicine specialists in New Zealand: A study to develop protocol guidelines. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 130, 43–51.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. How do primary care doctors compare to dentists in the referral of oral cancer? Evid.-Based Dent. 2021, 22, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.E.; Hummel, J. Oral Health in Primary Care: A Framework for Action. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2016, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, J.; Phillips, K.; Holt, B.; Hayes, C. Oral Health: An Essential Component of Primary Care; Qualis Health: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software]. McMaster University and Evidence Prime. 2024. Available online: https://www.gradepro.org (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Griffiths, P. Evidence informing practice: Introducing the mini-review. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2002, 7, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethman, M.P.; Carpenter, W.; Cohen, E.E.; Epstein, J.; Evans, C.A.; Flaitz, C.M.; Graham, F.J.; Hujoel, P.P.; Kalmar, J.R.; Koch, W.M.; et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding screening for oral squamous cell carcinomas. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. (1939) 2010, 141, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haider, S.S.; Martins, R.S.; Ali, R.; Rizvi, N.A.; Mustafa, M.A.; Aamdani, S.S.; Rehman, A.A.; Pervez, A.; Nadeem, S.; Siddiqui, H.K.; et al. Primary Care Clinical Practice Guidelines and Referral Pathways for Oral and Dental Diseases in Pakistan. Oral 2024, 4, 343-353. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral4030028

Haider SS, Martins RS, Ali R, Rizvi NA, Mustafa MA, Aamdani SS, Rehman AA, Pervez A, Nadeem S, Siddiqui HK, et al. Primary Care Clinical Practice Guidelines and Referral Pathways for Oral and Dental Diseases in Pakistan. Oral. 2024; 4(3):343-353. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral4030028

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaider, Syeda Sehrish, Russell Seth Martins, Rohaid Ali, Nashia Ali Rizvi, Mohsin Ali Mustafa, Salima Saleem Aamdani, Alina Abdul Rehman, Alina Pervez, Sarah Nadeem, Humayun Kaleem Siddiqui, and et al. 2024. "Primary Care Clinical Practice Guidelines and Referral Pathways for Oral and Dental Diseases in Pakistan" Oral 4, no. 3: 343-353. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral4030028