1. Introduction

Until the 1940s, translation represented the main methodological approach adopted for second language teaching [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, over the last few decades, the translation-oriented approach has been considered outdated and so was gradually replaced by the up-to-date direct method, in which a second language is taught without any association whatsoever to the student’s first language. The reason for this replacement, according to the direct view, is that teaching through translation would end up in false notions of equivalence as the translated language could sound artificial in the second language and would reinforce the second language processing via the first language [

2,

3].

Despite the criticism involving the use of translation as a means for language teaching and learning and the widespread adoption of the direct method, teachers and language instructors of the 21st century were challenged by the emergency and popularization of translation technologies such as Machine Translation systems (MT), especially with the free availability of popular tools such as Google Translate system (GT). Although the quality of the output of these systems was considered poor in their earlier stages of development [

4], advances in the field of Artificial Intelligence have brought about significant improvements to the MT output leading to an increase in MT users especially in the past five years. Way [

5] notes with respect to MT usage on Facebook that “with 2 billion translations being provided on a daily basis, and almost 1 billion users seeing these translations each month, the numbers are truly staggering”. According to Way [

6], GT translated an average of 143 billion words a day in 2016 (20 words/day for every person on the planet), just for a single (albeit the largest) MT service provider—across 100 language combinations, a doubling in translation volume in just 4 years. Hence, in contrast to the direct method claims, the availability of good quality web-based MT has made it possible for students to use translation tools as a support for language activities involving writing, reading and (possibly) speaking. Clifford [

7] emphasizes that the latest advances in this technology have the potential to influence the way students deal with second language learning, especially English learning due to its emergence as a

lingua franca and the language of science and business (See [

8] for a view that English will be the last lingua franca:

https://www.taus.net/think-tank/articles/translate-articles/mt-the-new-lingua-franca, accessed on 13 December 2020).

Even though language teachers and instructors restrict the use of MT in the classroom, the tool is often accessed at home by students to carry out their school work [

7]. Other than that, as the system is available in the form of mobile applications, it facilitates user access to translation in a communicative context. If English students, for instance, want to form a sentence in English but are uncertain as how to precisely structure the sentence, they can quickly translate the sentence using an MT application in their mobile device and be more confident in speaking. Thus, what we observe is a dilemma in which teachers, language instructors and academic institutions – based on the direct method claims—do not approve the use of translation as a means for language teaching and learning, while in contrast we see a widespread use of web-based translation tools that stimulate learning through translation.

Considering this dilemma, a question that deserves to be investigated is whether language learning is really compromized by the popularization and widespread use of MT tools. Although MT systems instantaneously produce a translation that can be rapidly processed by users, it is possible that MT users (un)consciously learn from that very MT output. According to several second language processing models, the bilingual mind has to operate simultaneously in two languages that are in competition during the process of language comprehension and production. Thus, this conflict must be resolved for successful communication to take place [

9]. We question here whether the use of MT systems is facilitating the resolution of this conflict, more specifically, facilitating the processing and acquisition of English syntactic structures.

We will focus in the present study on the English syntactic processing as the generation of syntactic structures in the second language is, as already previously outlined, challenging to speakers because it is a process that involves two languages in competition and, in many cases, syntactic structures that vary between a speaker’s first and second language. Moreover, in order to communicate a message either in one’s first or second language, more than one competing syntactic alternative could be used by speakers in a communicative context. For example, a speaker can deliver a message in English using both a passive structure (e.g., the boy has been kissed by the girl) or an active structure (e.g., the girl has kissed the boy). Another example would be verb phrases formulated with double objects (e.g., the boy gave the girl a book) versus prepositional object (e.g., the boy gave a book to the girl). Although these syntactic alternatives vary in terms of word order, they convey roughly the same meaning. In the second language, however, this process is exacerbated by the fact that some syntactic alternatives in the second language are not available in the first language. Thus, in these cases, during the processing of the second language, two conflicts must be resolved: (i) the competition between languages; and (ii) the competition between syntactic alternatives. At higher levels of language proficiency, adequacy and fluency of the message conveyed depend on the speakers’ language proficiency, while the syntactic alternative chosen depends not only on the speakers’ language proficiency but also on the context. The context involves the syntactic alternatives to which the speaker has been previously exposed to. Therefore, we believe it is worth investigating whether the interaction with web-based MT systems facilitates the processing of English syntax, especially the processing of syntactic alternatives that vary across a speaker’s first and second languages, thus posing to L2 English speakers additional processing challenges. We will examine how exposure to the MT preferred syntactic alternatives can influence a speaker’s syntactic choices while, at the same time, triggering syntactic learning if the syntactic alternative represents a challenging structure to be processed.

Some studies [

10,

11] show that, in the initial stages of second language acquisition, learners rely more on the lexical memory of single words, so they find difficulties and less automaticity in language tasks that involve proper combination of words in a sentence. Accordingly, it is at this stage and for that purpose that MT systems represent a source of support. Garcia and Pena [

12] showed that MT systems help beginners to communicate more in a foreign language and that, the lower the L2 level, the greater the difference between the number of words composed using MT and the number of words written directly in the L2. Therefore, this research will help us to understand whether MT systems are facilitating the acquisition of a fundamental ability for language learning: the ability to combine words in a sentence to properly convey ideas in a second language. Moreover, we aim at demystifying the assumption that MT systems are preventing students from progressing towards autonomously mastering English as a second language [

2]. We hypothesise that the MT output functions as a template for the re-use of syntactic structures, triggering in the subsequent utterance a syntactic learning process of that structure, especially those that differ between a speakers’ first and second language.

To test our general hypothesis, we examined the linguistic behaviour of Brazilian Portuguese speakers of English as a second language (L2 English) before and after performing a translation task involving sentences containing Prepositional Noun Phrases (e.g., The cover of the book is red) and the alternative Non-Prepositional Noun Phrase (e.g., The book cover is red) using an MT system. We chose to examine this language combination due to the differences in this syntactic construction between English and Portuguese. We address the following research questions:

Do L2 English speakers adapt their language behaviour to mirror the syntactic alternative of the MT when speaking in English?

If so, what are the factors that influence such behaviour?

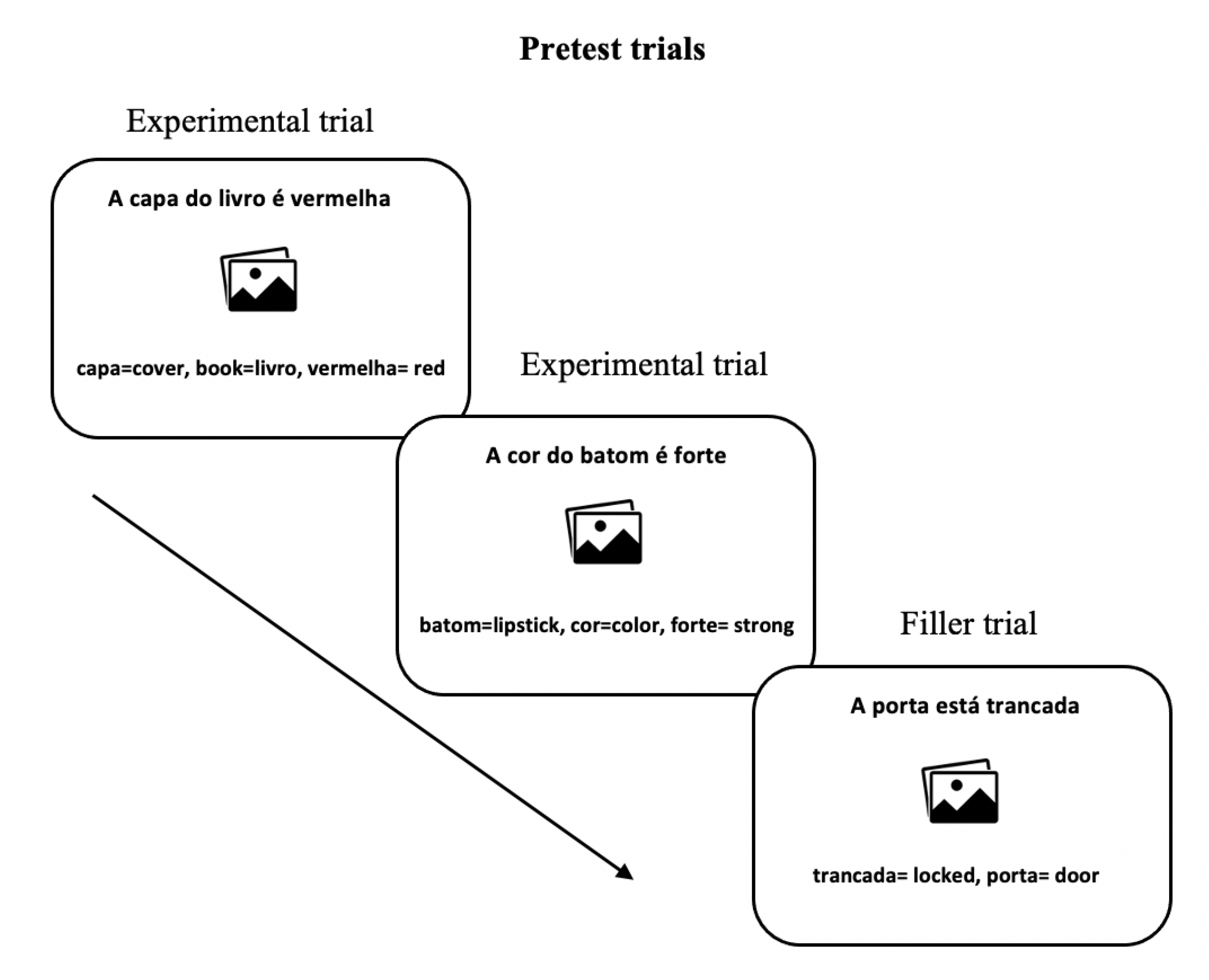

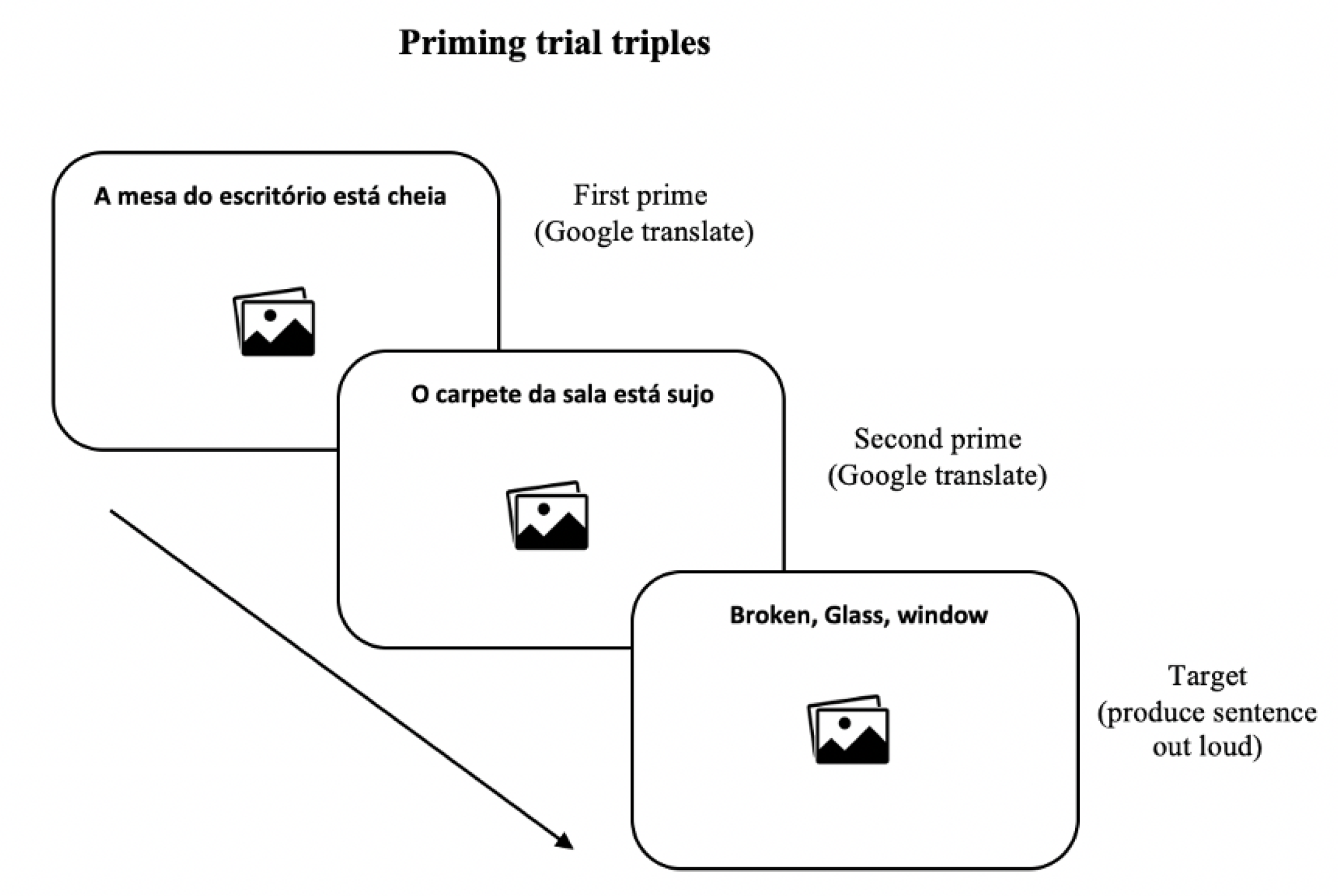

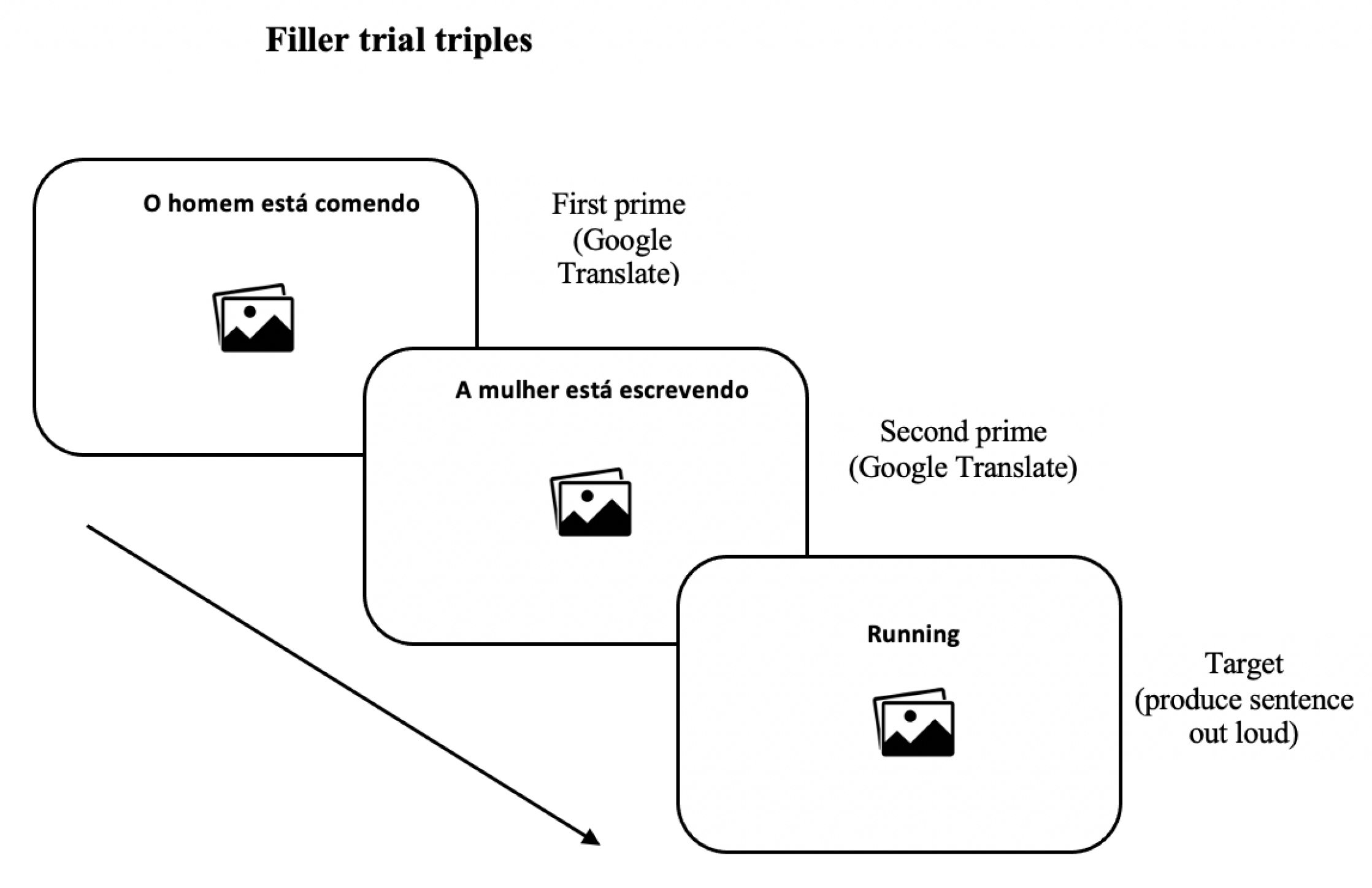

To answer our research questions, we first carried out a survey with the purpose of (i) understanding if and how MT systems were being used as a tool to support language learning; and (ii) if so, which web-based engines were the ones most frequently used. After conducting this survey, we carried out a syntactic priming study using a pre-test, priming, post-test design which allowed us to observe speakers’ linguistic behaviour before and after using an MT system. With this design, it was also possible to examine if any learning trends took place with continuous processing of the challenging syntactic structure in English, and if this learning was of an implicit (unconscious) or explicit (conscious) nature. In addition, we aimed at investigating whether any learning trends observed varied as a function of our participants’ English proficiency levels.

Before presenting our methodology in detail and the results of the two studies, we describe in the next section how the syntactic priming methodological approach has been used by researchers to investigate language syntactic processing both in the first and second language as well as in the interaction between humans and intelligent systems.

2. Syntactic Priming

Syntactic priming (also known as “structural priming” or “structural alignment”) can be defined as the facilitation of syntactic processing as a consequence of repetition of syntactic structures across consecutive sentences [

13,

14]. In language production experiments, the syntactic priming effect has been shown to manifest itself behaviourally as an increased tendency to re-use syntactic structures that have been produced either by the speaker or an interlocutor. This tendency to re-use the same syntactic structure previously processed has been demonstrated experimently for different structures [

15,

16,

17,

18], in different languages [

19,

20] and using different priming modalities [

21,

22]. Several studies also showed syntactic priming evidence between human interlocutors in L2 interactions [

23,

24,

25]. The results of these studies have revealed that less frequent syntactic structures prime more than more frequent structures do [

26]. For example, passive structures which are less frequently used by English and Dutch speakers prime more than active structures that are more frequently used [

15]. Some researchers call this effect the “inverse preference effect” and they claim that the most uncommon structures drive the priming effect [

27].

The first laboratory study that investigated the effect of repetition of the syntactic structure was conducted by Bock [

15]. Bock questioned whether the phenomenon was related to the maintenance of the syntactic structure representation in short-term memory or to implicit learning processes typical of a procedural mechanism. To address this issue, an experiment was conducted in which subjects listened to a sentence and had to describe an event represented in an image. The sentences contained four types of syntactic structure, namely: sentences with transitive verbs in the active voice (e.g.,

One of the fans punched the referee) and passive (e.g.,

The referee was punched by one of the fans); sentences with dative constructions containing double objects with (e.g.,

A rock climber sold some cocaine to an undercover agent) and without a preposition (e.g.,

A rock climber sold an undercover agent some cocaine). The images presented to the subjects for description varied in relation to whether the agent and patient of the events were animate or inanimate [±human]. The results revealed a tendency of English speakers to use the same syntactic structures of the phrases heard, i.e., active voice when listening to active voice, passive when exposed to passive etc., regardless of the order of the words in the sentence, the relationship between the event presented in the figure, the sentence heard or semantic factors such as the gender of the agent and the patient of the event. Based on these results, Bock concludes that the effect of repetition did not seem to be related to the temporary storage of the representation of the elements of a structure in working memory. In contrast, the effect of repetition seemed to be associated with more abstract processes typical of an independent mechanism of implicit nature responsible for syntactic processing. This suggests that the maintenance of the syntactic representation in short-term memory is not sufficient to explain the duration of the repetition phenomenon in long intervals of time.

Despite the differences in the methodological approach used in the studies mentioned as well as differences between the situations in which the phenomenon of repetition occurs, what these studies have in common is the influence exerted by the previous structure in the processing of the next structure. Given the presentation of a given syntactic structure, the chances that speakers produce sentences using that same structure increase. Traditionally, in laboratory studies that address the effect of repetition on syntactic processing, the sentence preceding the production event is called the

prime, and the sentence to be produced is called a

target. Therefore, if the production of the

target is influenced by the processing of the

prime structure, then the effect of syntactic priming is apparent. The syntactic priming effect refers thus to the facilitation of the processing of a syntactic structure as a result of the previous presentation of the same structure [

28,

29]. This facilitating effect of the structure presented above (prime), on a later structure (target) has been attributed to the reduction of the resources recruited for the processing of the target sentence [

15].

The syntactic priming effect has also been shown to manifest itself between humans and computers [

30]. Using a game in which a participant and their computer partners describe and match pictures, Cowan and colleagues [

31] found syntactic alignment in human-computer speech-based interactions for both dative structures (e.g.,

give the waitress an apple vs.

give the apple to the waitress) and noun phrase structures (e.g.,

a purple circle vs.

a circle that is purple). This demonstrates that a computer system can also influence a speaker’s grammatical choices in speech-based interactions. Virtual reality studies [

32] have also demonstrated syntactic alignment between humans and computer avatars for both passives and active structures.

Suzuki and Katagiri [

33] have found prosodic alignment between humans and computers. In their experiment, people exhibited alignment of loudness and response latency in their speech in response to computer-generated speech. Oviatt and colleagues [

34] found that children talking to computer partners spontaneously adapt several basic acoustic and prosodic features of their speech by 10–50%, with the largest adaptations involving utterance pause structure and amplitude. The study by Stoyanchev and Stent [

35] observed both lexical and syntactic alignment between humans and the

Let’s Go! system, which is a telephone-based spoken dialog that provides information about bus routes in Pittsburgh.

From the findings presented above, it is possible to conclude that, in an interactive context, speakers tend to syntactically align with their interlocutors both in first and second languages as well as with computer partners. Importantly, these studies show that syntactic priming plays a central role in successful communication since it can promote mutual understanding through the semantic and structural representations shared by interlocutors [

36].

The effect of syntactic priming has also been extensively observed not only in speech-based interactions, but also in the context of sentence comprehension. In general, these experiments deal with the reading of pairs or sequences of sentences that share the same syntactic structure. In such sequences, the first sentence is the prime and the second (or other sentences) the target. The purpose of these experiments is to investigate whether the cost of processing the target sentence is reduced in the face of the prime presentation. This reduction in the cost of processing was revealed by some behavioural studies whose results showed that target sentences are read faster than sentences that were not preceded by a prime. Traxler and Tooley [

37], for example, in two experiments using an eye tracker and two experiments using the self-paced reading paradigm, investigated the processing of sentences containing reduced subordinate sentences in English. The results showed that the processing of subordinate sentences is facilitated (as reflected by reduced fixation time and higher reading speed) when sentences are preceded by others with the same language structure. This reduction in the processing costs of sentences preceded by a prime has also been observed in electrophysiological studies. The study by Ledoux and colleagues [

38] indicates that the effect of prime on the comprehension of sentences is manifested in the attenuation of the amplitude of event-related potentials components associated with the processing of target sentences. In particular, it is also often associated with processes of reanalysis and repair of the syntactic structure [

28,

39].

It is noteworthy that the priming effect, both in speech-based interaction and in contexts of sentence comprehension, is magnified when the main verb of the prime sentence is repeated in the target sentence. In sets of sentences sharing the same syntactic structure, the reading time or fixation time of reading decreases if they contain the same structure and the same verb. This phenomenon is known as

lexical boost [

29]. In contexts of sentence comprehension, the effect of priming can only be observed if the main verb is repeated between the prime and the target(s) as the overlap of elements between prime and targets reinforces the activation of structural patterns present in prime processing, leading to a reduction in the cost of processing of the target sentences [

40].

Within the literature addressing syntactic priming, a question that has been frequently discussed is: what does the reduction in the cost of processing as a consequence of syntactic priming reflect? Most researchers assume that the effect of syntactic priming reflects learning automaticity [

15,

17,

27]. They explain that, when processing a syntactic structure, speakers of a language implicitly learn this structure, that is, they learn a type of abstract knowledge that is acquired unconsciously as an incidental consequence from the execution of some task. Thus, for this processing perspective, the prime would be responsible for activating changes in the system responsible for implicit learning processes. When reading, listening to or even uttering a sentence with a particular structure, the speaker activates and shapes this cognitive system.

If the effect of syntactic priming is the result of an implicit learning process and this process is established not only in production, but also in the reading comprehension of sentences, it is worthwhile reflecting on the following questions: (1) When reading the MT output, can a learning process emerge from the output comprehension? (2) If so, is this learning of an implicit (unconscious) or an explicit (conscious) nature? Investigating this question will bring insights into the role of intelligent systems has on the learning process of a second language.

Another important issue that should be considered in our investigation concerns the dependence on the effect of syntactic priming of the frequency of occurrence of the structure in the language. For example, in English and Dutch, active sentences are more frequent than sentences in the passive voice. In English, 88% of sentences occur in the active voice. In Dutch, this proportion is even higher, around 92% [

41]. Several experiments have revealed that the effect of syntactic priming is more evident for the less preferred structure of these languages, such as passive sentences [

15,

32,

42,

43]. If a given structure is less frequent in the language, then the effect of syntactic priming associated with that structure increases. Jaeger and Snider [

44] explain that the inverse effect of syntactic priming observed in the choice of a structure for production is the result of unexpected changes in the context of communication that shape the system responsible for implicit knowledge. In contrast, some production studies [

29,

41] showed that speakers are faster in producing the preferred structures than non-preferred structures. These findings suggest that, in fact, linguistic knowledge is obtained through a cognitive mechanism responsible for implicit learning, and that this mechanism can be modelled both by the linguistic experience acquired throughout life as well as by recent experiences. As shown, although the inverse preference effect was often observed in the examination of syntactic priming, most studies focused on English, Dutch and (to a lesser extent) German. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies to date that have used the syntactic priming methodology as a vehicle for investigating the processing and representation of Brazilian Portuguese syntax in the context of a human-artificial system interaction. Therefore, it is also necessary to investigate whether the inverse preference effect widely observed in languages such as English, Dutch and German also occurs in the syntactic processing of Portuguese, especially in the processing of the comprehension of sentences in Brazilian Portuguese.

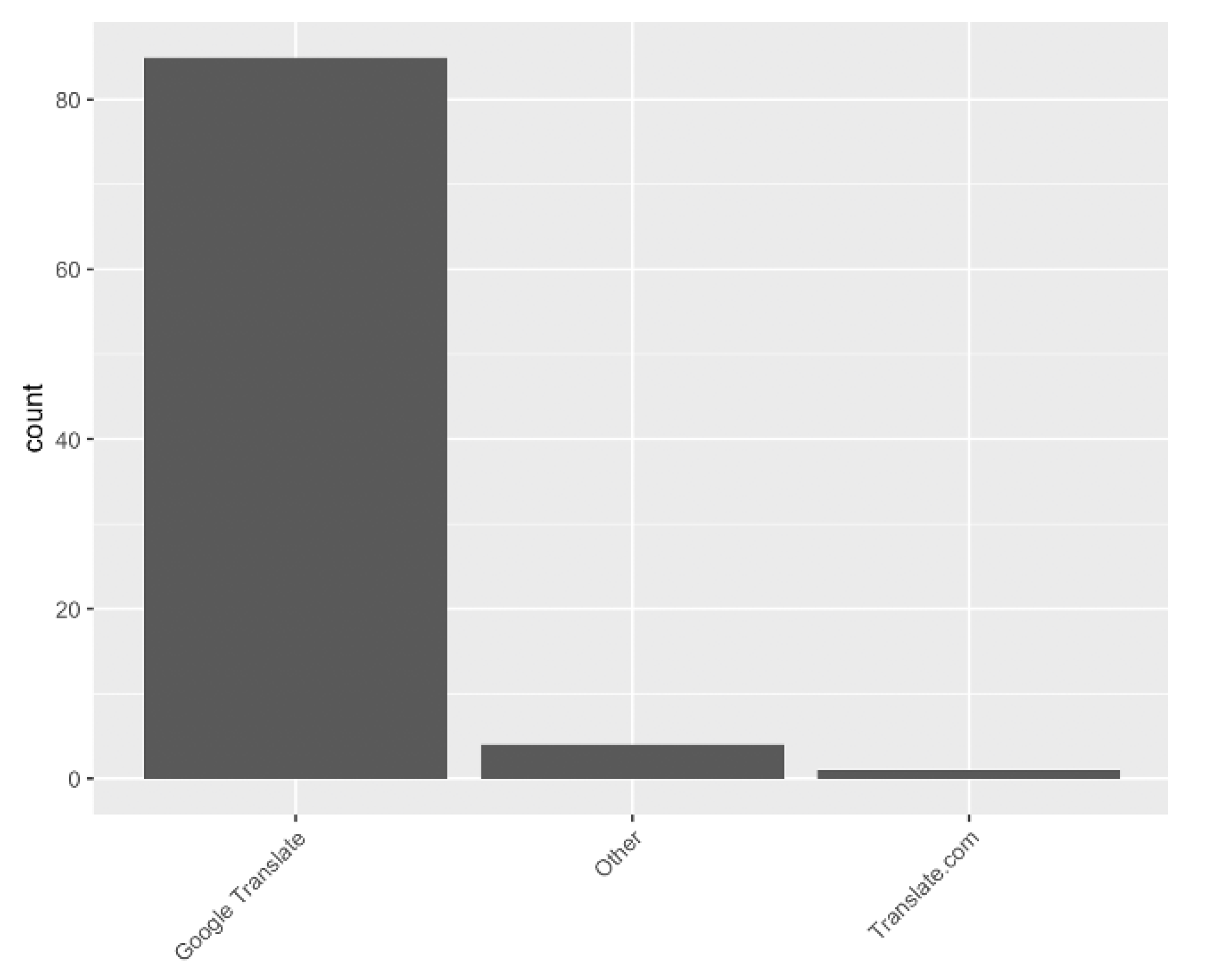

Before describing our experimental design and methodological approach, we present the results of a survey carried out with Brazilian Portuguese MT users which sought to understand if they have used or are using MT systems as a tool supporting their language learning process. We also investigate in this survey how students are interacting with the MT systems, what their preferred systems are and why they are using MT.

4. General Discussion and Conclusions

Our aim in this study was to investigate whether popular web-based MT systems can influence L2 English syntactic processing and elicit changes in the L2 English speakers’ linguistic behaviour. The general questions addressed were: (1) Do L2 English speakers adapt their language behaviour to mirror the MT system output when speaking in English? (2) If so, what are the factors that influence such changes?

To answer these questions, we first carried out a survey in which we investigated how Brazilian Portuguese L2 English students and speakers use popular web-based MT systems. The results of this survey showed that GT is the most popular system and that they have been using this MT service as a tool supporting tasks involving English vocabulary as well as English syntax. The survey also showed that the systems are more frequently used by respondents at intermediate and advanced English proficiency levels. The results of this survey were imperative to determine participants’ profiles as well as the MT system we should use when designing the syntactic priming experiment.

For the behavioural experiment, we tested 32 Brazilian Portuguese L2 English students at intermediate and advanced English proficiency with the aim of investigating whether after machine-translating sentences from Portuguese into English using GT, we would observe changes in their linguistic behaviour as a consequence of priming effects elicited by the MT output. The most important finding of our research is that a robust long-lasting priming effect was observed between the GT output and the participants as reflected by re-use of the GT preferred syntactic alternative in their subsequent English speech. Thus, this result indicates that L2 English speakers adapt their language behaviour to mirror the MT system output when speaking in English.

The results presented here replicated our previous findings [

45] as well as results from several studies in the field of Psycholinguistics (e.g., [

29,

32,

41,

43,

50,

51]) and HCI literature (e.g., [

31,

32]). The so-called

inverse preference effect, widely observed in psycholinguistic studies, was observed in the present study as participants re-used their least preferred syntactic alternative (the NP structures) when describing images in English after exposure to this syntactic alternative through GT output. Even though only around 8% of the MT output for the prime sentences was a PNP structure which is the participants’ most preferred structure and the easiest for them to process, it was GT’s NP structure that elicited the priming effect. Thus, the present study replicated the inverse preference effect reported in the literature, as the most challenging structure (in this case NP structures) became more frequent in the participants’ subsequent speech.

Our study has also shown a robust priming effect between a computer system (GT) and humans. Participants trusted the GT output enough to change their linguistic behaviour in order to mirror the system’s choices. This finding replicates results in the field of HCI indicating that priming effects can be elicited by computer systems or non-humans. In addition, our results show that a priming effect can be elicited not only between human-human interactions, but also between human-computer interactions.

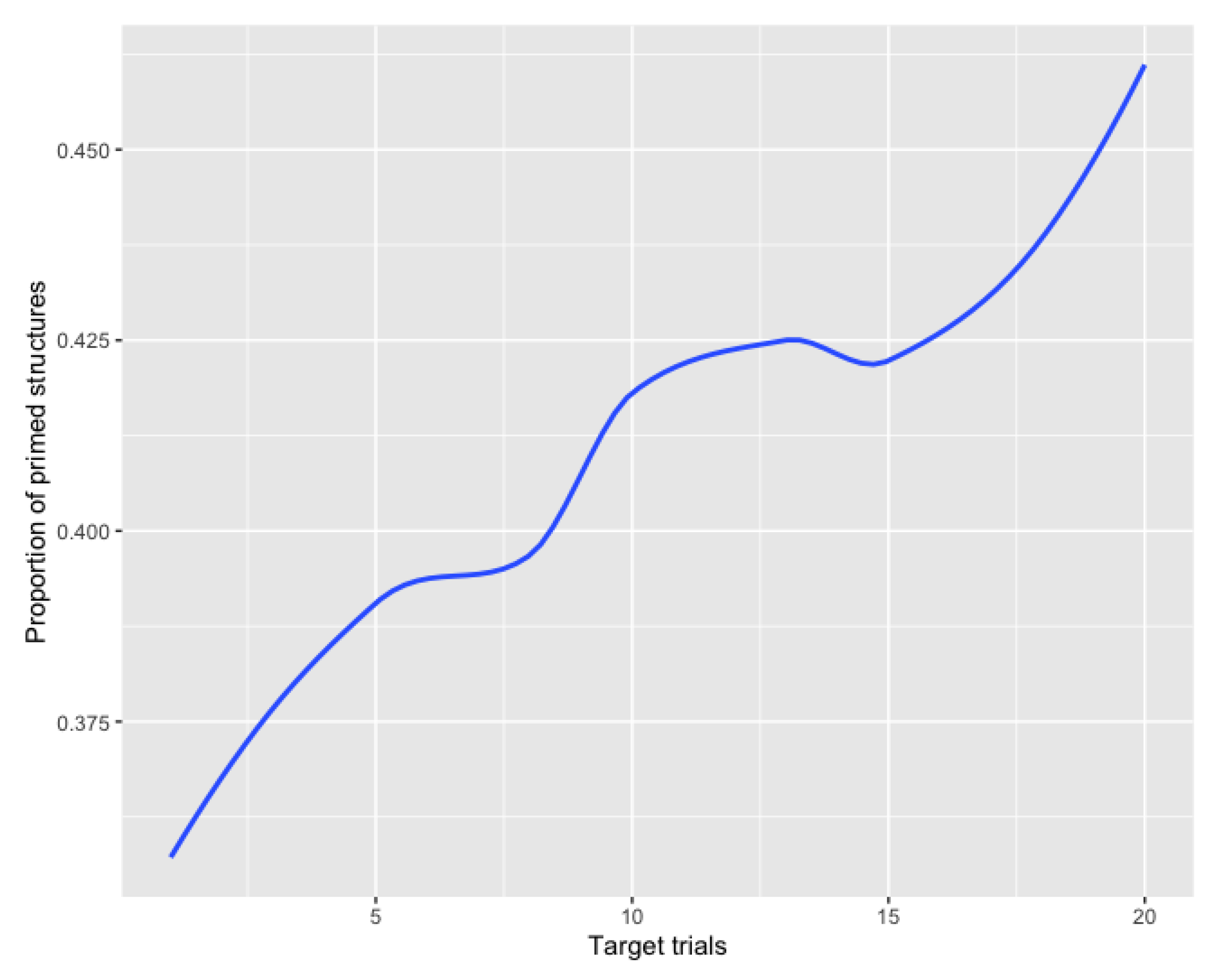

In addition to the priming effect, we observed a learning effect that emerged throughout the experiment sessions as the amount of NP structures produced by participants increased as the experiment progressed. The learning effect was then confirmed by the post-test results showing that even after 24 h’ exposure, participants were significantly (p < 0.001) more likely to produce an NP structure when tested on the same sentences than in the baseline pre-test. Both the learning effect emerging throughout the experiment session and the significant increase in the amount of NP structures produced in the post-test as compared to the baseline pre-test suggest that the learning effect observed in the present study was of an implicit nature. We validate this assumption based on the argument that if the effect had significantly diminished in the post-test, we could assume that the effect was short-lived and that participants re-used the structures due to simply storing them in their short-term memory. However, we observed that the priming effect was capable of reorganizing participants’ L2 syntactic processing mechanisms by changing their least preferred syntactic alternative to describe a relation of possession as their preferred one, even without the influence of the GT output. Another interesting finding is that the lack of interaction between post-test results and participants’ proficiency levels indicates that differences in proficiency levels did not influence in the persistence of the priming effect in the day following the priming session.

Based on the results described here, we conclude that the novelty of the present study lies in the observation that an MT system is capable of eliciting a long-lasting priming effect which results in implicit language learning of a challenging-to-process structure and reorganization of syntactic processing in the second language. The most important finding is that, contrary to the existing taboo involving translation as a method for language learning, our study shows that learning of L2 syntax can implicitly emerge from translation tasks and that knowledge can emerge from the interaction with a web-based MT system. The knowledge generated from this research is, therefore, of pedagogical relevance for the second language learning and teaching field. This study reveals that language instructors can assume a more optimistic perspective in relation to the use of MT systems with students, as our results show that (even unconsciously) students can learn from the MT output and such learning can be generalized by participants from a task involving comprehension (reading the translation) to a task involving production (speaking).

Additionally, we conclude that the syntactic priming paradigm represents an ecologically valid method to study MT-human interaction. Our study has obtained reliable results since they replicate findings of a number of previous studies in the fields of HCI Psycholinguistics. Thus, the methodology employed in the present study can be used by other researchers in different fields of research to address questions involving MT-human interaction.

It is worth mentioning that, although our results provide evidence as to whether influence of MT on English syntactic processing, it does not provide evidence whether GT can negatively influence English learning. We wonder whether MT pitfalls can be learnt and generalized by users when speaking or writing in English. Another limitation is that we tested a popular system; in future research, we aim to investigate whether a syntactic priming effect could be observed in the interaction between a less popular MT system and language learners. In addition, we aim at investigating whether it is possible to build an MT system constructed to train users’ language behaviour, and expose the participants to the output from this system, so this too remains an avenue for future work.