Examining the Post-School Decision-Making and Self-Determination of Disabled Young Adults in Ireland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the processes shaping causal and proxy agency for young adults, particularly disabled young adults, as they prepare to leave school in Ireland?

- (2)

- What role do early educational experiences, interpersonal relationships, parental expectations, and self-expectations play in the levels of self-determination among disabled and non-disabled young adults, while accounting for a diverse array of personal and contextual characteristics?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources: Growing Up in Ireland

2.2. Variable Description

2.3. Analytical Approach

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Logistic Regression Results

4. Discussion

Future Research/Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Individual Characteristics | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Boys | 50.6 |

| Girls | 49.4 | |

| Disability Type | No disability | 76.8 |

| Intellectual/general learning difficulties | 8.1 | |

| Specific learning difficulties | 5.2 | |

| Socioemotional/behavioural difficulties | 5.7 | |

| Physical/sensory/speech difficulties | 2.0 | |

| Other | 2.2 | |

| Economic Vulnerability (EV) | No EV | 66.8 |

| EV | 33.2 | |

| Books at Home | Had <30 books | 40.5 |

| Had 30 books or more | 59.6 | |

| Primary Caregiver (PCG)’s Education | No degree | 80.1 |

| Degree | 19.9 | |

| School DEIS Status | Non-DEIS | 78.9 |

| DEIS | 21.1 | |

| Parental Expectation at Age 9 | No 3rd-level degree expected | 28.0 |

| 3rd-level degree expected | 72.0 | |

| Educational Outcome at Age 20 | University degree/higher education or above | 37.1 |

| Non-university 3rd-level degree | 16.4 | |

| Non-university sub-degree | 6.9 | |

| Further education and training (FET) | 22.4 | |

| Did not finish programme | 4.8 | |

| No post-school education | 12.3 |

| Variable Name | Description |

|---|---|

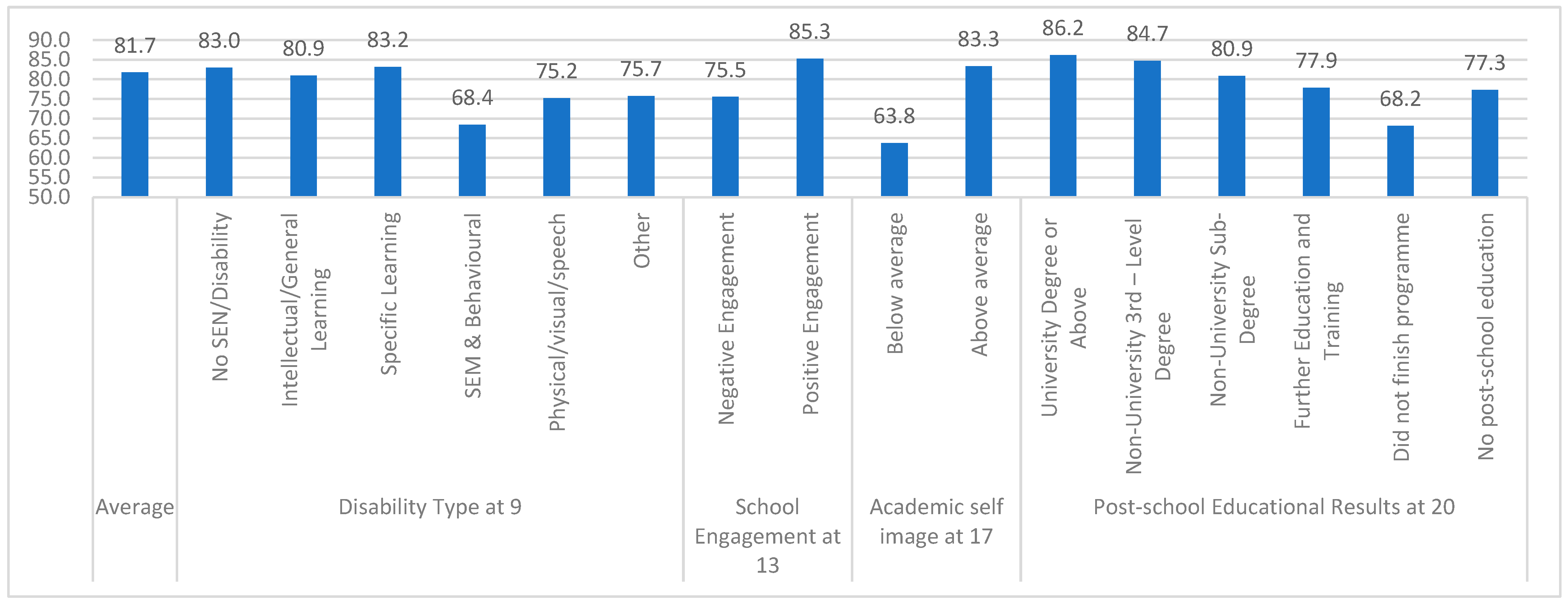

| Outcome variable | We examined students’ perceived decision-making and self-determination skills development using Wave 4 data from the Young Person Main Questionnaire. At age 20, young people were surveyed on how much their school helped them in areas such as ‘decide what to do after leaving school’, ‘think for yourself’, ‘prepare you for adult life’, ‘prepare you for the world of work’, ‘know how to acquire a new skill’, ‘know how to go about finding things out for yourself’, and ‘increase your self-confidence’. Responses were categorised as ‘a lot’, ‘some’, and ‘no help’. A binary variable was created to distinguish students with higher positivity towards self-determination skills support (top 81.7% of the scale) from those with lower positivity. |

| Individual characteristics | Gender and disability type at age 9 are independent variables exploring individual student characteristics. Teachers identified four primary disability types: physical, speech, learning, and emotional/behavioural difficulties. Primary caregivers (typically mothers) supplemented this information by identifying children with specific learning difficulties, communication disorders, or coordination issues. The teacher-reported Strengths and Difficulties Scale (SDQ) identified children with mental health or emotional/psychological challenges. Children identified by caregivers as experiencing hampered daily activities, ‘slow progress’, or speech and communication difficulties are categorised as ‘other’ if not classified under the four main disability types. In cases of multiple disabilities, children are categorised according to the type of disability most likely to impact their academic performance (e.g., a child with both general learning/intellectual and physical disabilities is categorised as having a general learning/intellectual disability). |

| Family resources | Family resources in this study consider socioeconomic indicators, cultural and social capital, and the broader community environment. Parental education, defined as the highest educational attainment of the primary caregiver (usually mothers), is constructed as a binary variable (third-level degree or not) using Wave 1 data. Economic vulnerability is a composite measure derived from latent class analysis, covering income poverty, household joblessness, and financial strain using the first three waves of data. Additionally, the number of books in the home at age 9 serves as a measure of social and cultural capital, reflecting investment in achievement during middle childhood. Neighbourhood characteristics are also considered, as they provide critical contexts for adolescent development. Neighbourhood characteristics were captured through students’ responses to the statement ‘This [neighbourhood] is a safe area’ at age 17, using a four-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. |

| Academic achievement | Academic achievement is closely associated with self-determination skills development. We use Drumcondra reasoning test scores at age 13 to capture academic performance in earlier years. Students’ educational pathways at age 20 (Higher Education, Further Education and Training, or other) serve as indicators of more recent academic performance. |

| School engagement | School engagement was assessed through students’ responses to the question, ‘How do you feel about school in general?’ using a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘I like it very much’ to ‘I hate it’ at Wave 2, with positive engagement indicated by liking school and negative engagement reflecting dislike. The quality of interactions between students and teachers was captured by students’ self-reported conflict levels with teachers at age 13, based on instances of the student being reprimanded for misbehaviour or untidy/late work by their teacher. School absence in this study was measured by the number of school days missed at age 9 based on teacher reports, with students missing over 10 days classified as having higher absenteeism. |

| Parental educational expectation | Parental educational expectations were measured by the primary caregiver’s anticipation regarding their child’s post-secondary educational path at age 9. A binary variable distinguishes between expectations of achieving a third-level degree and all others. |

| Self-expectation | Young people’s self-expectations were assessed by their academic self-image relative to peers at age 17, using a binary variable to differentiate those perceiving above-average performance from others. |

| School characteristics | The socioeconomic profile of schools was captured by students’ participation in the DEIS programme, which supports schools with a high prevalence of socially disadvantaged students. A binary variable was created to distinguish students attending DEIS schools from those in non-DEIS schools at any wave of data collection. |

References

- Newman, L.A.; Madaus, J.W. An Analysis of Factors Related to Receipt of Accommodations and Services by Postsecondary Students With Disabilities. Remed. Spec. Educ. 2015, 36, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackorby, J.; Wagner, M. Longitudinal Postschool Outcomes of Youth with Disabilities: Findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study. Except. Child. 1996, 62, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, E.; McCoy, S.; Mihut, G. Exploring Cumulative Disadvantage in Early School Leaving and Planned Post-school Pathways among Those Identified with Special Educational Needs in Irish Primary Schools. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 48, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, E.; Ye, K.; McCoy, S. Educationally Maintained Inequality? The Role of Risk Factors and Resilience at 9, 13 and 17 in Disabled Young People’s Post-School Pathways at 20. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2022, 41, 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheochari, S.; Platt, L. Disability Differentials in Educational Attainment in England: Primary and Secondary Effects. Br. J. Sociol. 2019, 70, 502–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, K.W. Disability Simulations: Using the Social Model of Disability to Update an Experiential Educational Practice. Schole: J. Leis. Stud. Recreat. Educ. 2012, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, C.; Stalker, K. Children’s Experiences of Disability: Pointers to a Social Model of Childhood Disability. Disabil. Soc. 2006, 22, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A.; Beckett, A.E. The Social and Human Rights Models of Disability: Towards a Complementarity Thesis. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2021, 25, 348–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Self-Efficacy Beliefs as Shapers of Children’s Aspirations and Career Trajectories. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abery, B.H.; Karapetyan, L. Supporting the Self-Determination of Students with Special Education Needs in the Inclusive Classroom. In Inclusive Education Strategies: A Textbook; Tichá, R., Abery, B.H., Johnstone, C., Poghosyan, A., Hunt, P.F., Eds.; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA; UNICEF Armenia & Armenian State Pedagogical University: Yerevan, Armenia, 2018; pp. 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Abery, B.H.; Ticha, R.; Smith, J.G.; Grad, L. Assessment of the Self-Determination of Adults with Disabilities via Behavioral Observation: SD-CORES. 2017. (Unpublished work).

- Gothberg, J.E.; Greene, G.; Kohler, P.D. District Implementation of Research-Based Practices for Transition Planning With Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Youth With Disabilities and Their Families. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2019, 42, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.; Lamptey, D.-L.; Cagliostro, E.; Srikanthan, D.; Mortaji, N.; Karon, L. A Systematic Review of Post-Secondary Transition Interventions for Youth with Disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 2492–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindstrom, L.; DeGarmo, D.; Khurana, A.; Hirano, K.; Leve, L. Paths 2 the Future: Evidence for the Efficacy of a Career Development Intervention for Young Women With Disabilities. Except. Child. 2020, 87, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, A.R.; Rifenbark, G.G.; Rogers, H.J.; Swaminathan, H.; Taconet, A.; Mazzotti, V.L.; Morningstar, M.E.; Wu, R.; Langdon, S. Establishing Construct Validity of a Measure of Adolescent Perceptions of College and Career Readiness. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2023, 46, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.B.; Song, J.Z.; Luong, D.; Perrier, L.; Bayley, M.T.; Andrew, G.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.; Chan, B.; Curran, C.J.; Dimitropoulos, G.; et al. Transitional Care Interventions for Youth With Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, P.-C. Using Self-Determination of Senior College Students with Disabilities to Predict Their Quality of Life One Year after Graduation. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, K.A.; Wehmeyer, M.L.; Palmer, S.B.; Rifenbark, G.G.; Little, T.D. Relationships Between Self-Determination and Postschool Outcomes for Youth With Disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. 2015, 48, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, K.A.; Shaw, L.A. The Impact of Personal Factors on Self-Determination and Early Adulthood Outcome Constructs in Youth With Disabilities. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2017, 27, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.; Migliore, A.; Butterworth, J. Self-Determination, Social Skills, Job Search, and Transportation: Is There a Relationship with Employment of Young Adults with Autism? JVR 2016, 45, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, L.; Ferrari, L.; Soresi, S.; Wehmeyer, M. Self-determination, Social Abilities and the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2007, 51, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, K.A.; Broussard, R. Exploring the Perceptions of Self-Determination of Individuals With Intellectual Disability. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 49, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, E.; Mumbardó-Adam, C.; Guillén, V.M.; Coma-Roselló, T.; Bravo-Álvarez, M.-Á.; Sánchez, S. Self-Determination in People with Intellectual Disability: The Mediating Role of Opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehmeyer, M.L. The Importance of Self-Determination to the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disability: A Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, E.E.; Kirby, A.V.; Hagiwara, M.; Shogren, K.A.; Ersan, D.T.; Brown, S. Family Role in the Development of Self-Determination for Youth With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Scoping Review. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 59, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishna, F.; Muskat, B.; Farnia, F.; Wiener, J. The Effects of a School-Based Program on the Reported Self-Advocacy Knowledge of Students With Learning Disabilities. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 57, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, S.; Sarver, M.D.; Shaw, S.F. Self-Determination: A Key to Success in Postsecondary Education for Students with Learning Disabilities. Remed. Spec. Educ. 2003, 24, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, B.; Klinger, L.G.; Pugliese, C.E. Self-Determination in Autistic Transition-Aged Youth without Intellectual Disability. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 4067–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrels, V.; Palmer, S.B. Student-Directed Learning: A Catalyst for Academic Achievement and Self-Determination for Students with Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 24, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, B.; Kraemer, B.; Steinbrenner, J.R.; Smith DaWalt, L.; Hall, L.J.; Hume, K.; Odom, S. Student, Educator, and Parent Perspectives of Self-Determination in High School Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 2164–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.W.; Lane, K.L.; Pierson, M.R.; Glaeser, B. Self-Determination Skills and Opportunities of Transition-Age Youth with Emotional Disturbance and Learning Disabilities. Except. Child. 2006, 72, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Convention On The Rights Of Persons With Disabilities—Articles. Available online: https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-articles (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Office of the Attorney General Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015. Available online: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2015/act/64 (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Department of Education Special Education. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation-information/b05378-special-education-section/ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Kenny, N.; McCoy, S.; Mihut, G. Special Education Reforms in Ireland: Changing Systems, Changing Schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education and Skills. DEIS Plan 2017: Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/24451/ba1553e873864a559266d344b4c78660.pdf#page=null (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Smyth, E.; McCoy, S. Investing in Education: Combating Educational Disadvantage; ESRI: Dublin, Ireland, 2009; ISBN 0-7070-0280-X. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Systems Theory. Ann. Child Dev. 1989, 6, 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. Handb. Child Psychol. 2007, 1, 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Greene, S.; Doyle, E.; Harris, E.; Layte, R.; McCoy, S.; McCrory, C.; Murray, A.; Nixon, E.; O’Dowd, T. Growing Up in Ireland National Longitudinal Study of Children. The Lives of 9 Year Olds; The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4064-2450-8. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, E.; Murphy, D.; Murray, A.; Smyth, E.; Watson, D. Growing up in Ireland: The Lives of 17/18-Year-Olds of Cohort’98 (Child Cohort); Government Publications: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, E.; O’Reilly, C.; Murray, A.; O’Mahony, D.; Williams, J.; Murphy, D.; McClintock, R.; Watson, D. Growing Up in Ireland-National Longitudinal Study of Children: Design, Instrumentation and Procedures for Cohort’98 (Child Cohort) at Wave 4 (20 Years of Age); Government Publications: Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, S.; Maître, B.; Watson, D.; Banks, J. The Role of Parental Expectations in Understanding Social and Academic Well-Being among Children with Disabilities in Ireland. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2016, 31, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, C.T.; Watson, D.; Maître, B.; Williams, J. Family Economic Vulnerability & the Great Recession: An Analysis of the First Two Waves of the Growing Up in Ireland Study. LLCS 2015, 6, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.; Quail, A.; Smyth, E. Growing Up in Ireland: Influences on 9-Year-Olds’ Learning: Home, School and Community; Government Publications: Dublin, Ireland, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4064-2642-7. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.; McDermott, E.R.; Elliott, M.C.; Donlan, A.E.; Aasland, K.; Zaff, J.F. Youth-Serving Institutional Resources and Neighborhood Safety: Ties with Positive Youth Development. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2018, 88, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milam, A.J.; Furr-Holden, C.D.M.; Leaf, P.J. Perceived School and Neighborhood Safety, Neighborhood Violence and Academic Achievement in Urban School Children. Urban Rev. 2010, 42, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Gaumer Erickson, A.; Kingston, N.M.; Noonan, P.M. The Relationship Among Self-Determination, Self-Concept, and Academic Achievement for Students With Learning Disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 2014, 47, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaumer Erickson, A.S.; Noonan, P.M.; Zheng, C.; Brussow, J.A. The Relationship between Self-Determination and Academic Achievement for Adolescents with Intellectual Disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 36, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, S.; Banks, J. Simply Academic? Why Children with Special Educational Needs Don’t like School. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2012, 27, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, U. Student Engagement, Academic Self-Efficacy, and Academic Motivation as Predictors of Academic Performance. Anthropologist 2015, 20, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiu, L.; Sun, B. School Engagement as a Mediator in Students’ Social Relationships and Academic Performance: A Survey Based on CiteSpace. IJCS 2021, 5, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, B.A.; Hajovsky, D.B.; McCune, L.A.; Turek, J.J. Conflict, Closeness, and Academic Skills: A Longitudinal Examination of the Teacher–Student Relationship. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 46, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.; Murray, E.; Phillipson, S. Student–Teacher Relationships and Student Self-Concept: Relations with Teacher and Student Gender. Aust. J. Educ. 2016, 60, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M. The Effects on Students’ Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties of Teacher–Student Interactions, Students’ Social Skills and Classroom Context. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 40, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.; Sosu, E.M.; Dare, S. School Absenteeism and Academic Achievement: Does the Reason for Absence Matter? AERA Open 2022, 8, 233285842110711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, N.N. Adolescent Adversity, School Attendance and Academic Achievement: School Connection and the Potential for Mitigating Risk. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottfried, M.A.; Kirksey, J.J. “When” Students Miss School: The Role of Timing of Absenteeism on Students’ Test Performance. Educ. Res. 2017, 46, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champaloux, S.W.; Young, D.R. Childhood Chronic Health Conditions and Educational Attainment: A Social Ecological Approach. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Fienup, D.M. Increasing Access to Online Learning for Students with Disabilities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Spec. Educ. 2022, 55, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lee, M.; Gershenson, S. The Short-and Long-Run Impacts of Secondary School Absences. J. Public Econ. 2021, 199, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.; Quail, A.; Smyth, E. The Effects of School Social Mix: Unpacking the Differences. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2014, 33, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.; Banks, J.; Shevlin, M. Insights into the Prevalence of Special Educational Needs. In Cherishing All the Children Equally? Ireland 100 Years on from the Easter Rising; Williams, J., Nixon, E., Smyth, E., Watson, D., Eds.; Oak Tree Press: Cork, Ireland, 2016; Chapter 8; pp. 153–174. Available online: https://www.esri.ie/publications/insights-into-the-prevalence-of-special-educational-needs (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Young, N.A.E. Childhood Disability in the United States: 2019. ACSBR-006. U.S. Census Bureau, 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2021/acs/acsbr-006.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Seen, Counted, Included: Using Data to Shed Light on the Well-Being of Children with Disabilities; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, S.; Varahra, A. A Systematic Review of Self-Determination Interventions for Children and Youth with Disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 5341–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, I.-C.; Molina, R.M. Self-Determination of College Students with Learning and Attention Challenges. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2019, 32, 359–375. [Google Scholar]

- Abery, B.H.; Stancliffe, R.J. An Ecological Theory of Self-Determination: Theoretical Foundations. Theory Self-Determ. Found. Educ. Pract. 2003, 25, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, B.A. Improving Transition Domains by Examining Self-Determination Proficiency among Gender and Race of Secondary Adolescents with Specific Learning Disabilities; Kansas State University: Manhattan, KS, USA, 2010; ISBN 1-124-42766-X. [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeyer, M.; Lawrence, M. Whose Future Is It Anyway? Promoting Student Involvement in Transition Planning. Career Dev. Except. Individ. 1995, 18, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, A.A. Self-Determination Perceptions and Behaviors of Diverse Students with LD During the Transition Planning Process. J. Learn. Disabil. 2005, 38, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shogren, K.A.; Scott, L.A.; Hicks, T.A.; Raley, S.K.; Hagiwara, M.; Pace, J.R.; Gerasimova, D.; Alsaeed, A.; Kiblen, J.C. Exploring Self-Determination Outcomes of Racially and Ethnically Marginalized Students With Disabilities in Inclusive, General Education Classrooms. Inclusion 2021, 9, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.S.; Leake, D. Teachers’ Views of Self-Determination for Students with Emotional/Behavioral Disorders: The Limitations of an Individualistic Perspective. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2011, 26, 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Chiu, H.-M.; Sin, K.-F.; Lui, M. The Effects of School Support on School Engagement with Self-Determination as a Mediator in Students with Special Needs. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2022, 69, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavendish, W.; Connor, D.J.; Perez, D. Choice, Support, Opportunity: Profiles of Self-Determination in High School Students with Learning Disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Multidiscip. J. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Jimenez, A.L.; Kershner, R. Transition to Independent Living: Signs of Self-determination in the Discussions of Mexican Students with Intellectual Disability. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2021, 49, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, I.; Vandenbossche-Makombo, J.; Fraser, S.L. Students’ Oppositional Behaviors and Engagement in School: The Differential Role of the Student-Teacher Relationship. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, K.A.; Plotner, A.J. Transition Planning for Students With Intellectual Disability, Autism, or Other Disabilities: Data from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 50, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandroo, R.; Strnadová, I.; Cumming, T.M. A Systematic Review of the Involvement of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Transition Planning Process: Need for Voice and Empowerment. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 83, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandroo, R.; Strnadová, I.; Cumming, T.M. Is It Really Student-Focused Planning? Perspectives of Students with Autism. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 107, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathmann, K.; Herke, M.; Bilz, L.; Rimpelä, A.; Hurrelmann, K.; Richter, M. Class-Level School Performance and Life Satisfaction: Differential Sensitivity for Low- and High-Performing School-Aged Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.; Smyth, E.; Watson, D.; Darmody, M. Leaving School in Ireland: A Longitudinal Study of Post-School Transitions. ESRI Res. Ser. 2014, 36, 2015-07. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 5.515 *** | 4.482 *** | 4.718 *** | 4.133 *** |

| Female (Base: Male) | 0.806 ** | 0.832 * | 0.716 *** | 0.679 *** |

| Disability (Base: No disability) | ||||

| Intellectual/general learning | 0.751 # | 0.721 # | 0.671 # | 0.766 |

| Specific learning | 1.061 | 1.131 | 1.066 | 1.163 |

| Socio-emotional and behavioural | 0.503 *** | 0.533 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.553 *** |

| Physical/visual/hearing/speech | 0.650 # | 0.673 # | 0.720 | 0.711 |

| Other | 0.604 * | 0.597 * | 0.615 # | 0.657 |

| Economic vulnerability at wave 1, 2 or 3 (Base: No economic vulnerability) | 0.724 *** | 0.711 *** | 0.757 ** | |

| Parent has 3rd level degree (Base: Lower education) | 1.01 | 1.006 | 0.953 | |

| Had >30 books in house at 9 (Base: 30 books or less) | 0.757 *** | 0.793 ** | 0.782 ** | |

| Lived in a safe neighbourhood at 17 (Base: unsafe neighbourhood) | 1.762 *** | 1.786 *** | 1.66 *** | |

| Attended DEIS school at 9, 13 or 17 (Base: Did not attend DEIS school in any wave) | 0.997 | 0.983 | 1.064 | |

| Parental expectation at 9: 3rd level degree (Base: No 3rd level degree expected) | 0.91 | 0.934 | 0.851 | |

| More than 10 days of school missed at 9 (Base: missed 10 days or less) | 0.724 ** | 0.750 ** | ||

| Teacher conflict at 13 (Base: No teacher conflict) | 0.792 * | 0.888 | ||

| Positive school engagement at 13 (Base: Less positive) | 1.613 *** | 1.539 *** | ||

| Drumcondra test score at 13 (Base: Lowest quintile/1st quintile) | ||||

| 2nd quintile | 0.794 | 0.683 ** | ||

| 3rd quintile | 0.900 | 0.693 ** | ||

| 4th quintile | 0.739 # | 0.533 *** | ||

| 5th quintile | 0.693 * | 0.483 *** | ||

| Above-average academic self-image at 17 (Base: Average or below) | 2.381 *** | |||

| Post-school educational outcome (Base: University 3rd level degree) | ||||

| Non-university 3rd level degree | 0.860 | |||

| Non-university sub-degree | 0.559 *** | |||

| Further education and training | 0.496 *** | |||

| Did not finish programme | 0.499 *** | |||

| No post-school education | 0.520 *** | |||

| N of observation | 4681 | 4661 | 4164 | 4162 |

| N of schools | 837 | 836 | 789 | 789 |

| Pseudo R-square | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.033 | 0.054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, K.; McCoy, S. Examining the Post-School Decision-Making and Self-Determination of Disabled Young Adults in Ireland. Disabilities 2024, 4, 459-476. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030029

Ye K, McCoy S. Examining the Post-School Decision-Making and Self-Determination of Disabled Young Adults in Ireland. Disabilities. 2024; 4(3):459-476. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030029

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Keyu, and Selina McCoy. 2024. "Examining the Post-School Decision-Making and Self-Determination of Disabled Young Adults in Ireland" Disabilities 4, no. 3: 459-476. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030029

APA StyleYe, K., & McCoy, S. (2024). Examining the Post-School Decision-Making and Self-Determination of Disabled Young Adults in Ireland. Disabilities, 4(3), 459-476. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030029