Abstract

In today’s job market, effective social communication is crucial for employment success. We investigated “Cog ‘n’ Role”, a novel video modeling (VM) intervention that integrates video self-modeling (VSM) and social problem-solving therapy (SPST) to enhance socio-vocational skills in individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs). The intervention is delivered via “PowerMod”, an application featuring ready-to-use VM scenarios and enhanced accessibility options; our aim was to examine (a) the app’s social validity and (b) the effectiveness of the intervention in improving job-related social skills. Thirty-four adults with IDD used “PowerMod” to view video clips of common workplace scenarios and rated their experiences through questionnaires. Subsequently, seventeen adults who have social difficulties at work participated in four weekly therapy sessions featuring the “Cog ‘n’ Role” intervention via the PowerMod app. Socio-vocational skills were measured through questionnaires filled out by their counselors; participants found the adapted video clips to be significantly more comprehensible and relevant compared to non-adapted video clips. Additionally, the intervention group showed significant improvements in socio-vocational behaviors and a significant transition to jobs that required higher levels of independence. These findings provide preliminary evidence for the impact of this innovative intervention in enhancing socio-vocational skills among individuals with mild to moderate IDD.

1. Introduction

Employment is a significant challenge in the lives of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs). As with typical adults, being gainfully employed profoundly affects self-perception, sense of community, overall well-being, and quality of life [1,2]. Nevertheless, data consistently show that most employed individuals with IDD work part-time in entry-level positions with low incomes and limited access to employee benefits [3].

When evaluating job applicants, employers typically prioritize soft skills such as problem-solving, creativity, and social intelligence [4,5,6]. It is therefore important to acknowledge the role of social intelligence, a key component of soft skills, which refers to the ability to accurately assess others’ emotional states and respond appropriately through verbal content, tone of voice, and gestures [7,8,9]. In workplace settings, social intelligence enables employees to interpret implicit social cues, manage interpersonal dynamics, and adapt to changing social expectations [5]. This ability, often linked to Theory of Mind [10], plays a crucial role in workplace interactions and team dynamics.

Individuals with IDD often face significant challenges in developing and applying soft skills. They may struggle with impulse control, exhibit dependent or aggressive behaviors, or, in some cases, demonstrate inappropriate social responses such as sexually inappropriate behavior [11,12,13,14]. These difficulties in social interaction serve as substantial barriers to workforce integration, frequently resulting in economic and social dependence on family support [3,15].

Individuals with IDD face significant challenges in workplace interactions, particularly in understanding social norms, engaging in appropriate workplace behavior, and managing interactions with colleagues and customers [16]. These difficulties align with impairments in social intelligence. Given these challenges, interventions that explicitly target the development of social intelligence and adaptive workplace interactions are essential. However, traditional vocational training programs for individuals with IDD tend to focus on technical and task-related skills, placing less emphasis on the nuanced social and problem-solving abilities required for sustained employment [17]. To bridge this gap, evidence-based approaches such as video modeling (VM) and social problem-solving therapy (SPST) provide structured and effective methods for teaching complex socio-vocational skills [18,19].

With appropriate support tailored to their functional abilities and needs, individuals with IDD can successfully gain and maintain employment [20]. While some individuals may secure competitive jobs in the open labor market, many initially require structured employment frameworks such as sheltered workshops, particularly for those who need long-term support [21,22]. Sheltered workshops provide job skills training in a segregated setting, whereas supported employment programs facilitate community-integrated job placements with ongoing supervision [22]. Research indicates that targeted interventions, such as structured vocational training, provide individuals with IDD the social and vocational skills necessary for more independent work settings, allowing them to transition from sheltered employment to supported employment (e.g., through personalized interventions) [20].

When designing interventions for individuals with IDD, it is essential to ensure that programs are not only effective but also socially valid, i.e., they are acceptable, relevant, and meaningful, while providing a positive user experience for both participants and their caregivers [23]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends incorporating social validity principles to enhance care-receivers’ engagement, adherence, and the overall success of interventions [23,24].

Research in this field emphasizes that interventions should not only yield measurable outcomes but also be perceived as acceptable, beneficial, and meaningful from the participants’ standpoint. Social validity assessments are widely recommended to ensure that interventions align with the needs and expectations of individuals with IDD, their caregivers, and professionals. By prioritizing social validity, interventions can be refined to enhance their practical application and long-term sustainability [25].

Moreover, given that individuals with severe disabilities, including IDD, often have limited opportunities for choice and decision-making in their daily lives, ensuring the social validation of evaluation and intervention tools is particularly crucial [26]. Socially validated assessments are widely applied across rehabilitation, special education, and behavioral science fields to enhance the relevance and usability of interventions [25,27,28]. Integrating social validity into assessment and intervention design helps refine goals, optimize procedures, ensure implementation fidelity, and establish a foundation for selecting evidence-based methods tailored to the needs and preferences of participants [29]. Ultimately, this approach fosters a more user-friendly and effective experience.

Video modeling (VM) achieves learning through observation, as first presented by [30]. This evidence-based method involves individuals who lack proficiency in desired behaviors being given opportunities to view video clips demonstrating appropriately performed behaviors and then practicing them [31]. VM has been effective in improving social, vocational, academic, and self-care skills among both neurotypical individuals, such as caregivers and therapists, and people with disabilities, including those with autism and IDD [32,33,34,35,36]. A notable subset of VM is video self-modeling (VSM) [37], a self-observation-based learning approach that allows individuals to observe themselves behaving adaptively. Participants are video-recorded performing an activity and given external cues to achieve a more adaptive performance. They then view the recorded adapted performance [38].

Social problem-solving therapy (SPST) is another evidence-based approach based on the cognitive behavioral therapy model (CBT), designed to train individuals to cope more effectively with various life stressors [39]. It entails guided discovery, which involves asking questions to raise awareness of feelings and thoughts that drive behavior, role-playing to test and practice new behaviors, and positive reinforcement [40,41,42].

In the workplace, problem-solving skills are essential for handling misunderstandings with employers and colleagues, responding appropriately to feedback, and navigating unexpected challenges [43]. Individuals with IDD, who may struggle with these adaptive responses, can particularly benefit from problem-solving interventions to enhance their ability to analyze workplace situations, consider multiple solutions, and apply effective strategies to maintain employment stability [20].

VM and SPST may complement each other as interventions that support individuals with IDD in acquiring both observable workplace behaviors and the cognitive flexibility needed for adaptive social interactions. VM facilitates learning through observation and repetition, making it particularly effective for individuals with IDD, who often benefit from structured visual learning methods [44]. At the same time, SPST enhances this process by providing a structured framework for developing higher-order social reasoning skills, enabling individuals to analyze workplace interactions, anticipate consequences, and respond appropriately to social cues [45]. In combination, these methods offer a comprehensive approach to improving socio-vocational skills, bridging the gap between technical job training and the interpersonal demands of the workplace.

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of VM in skill acquisition for individuals with IDD, its application in vocational settings remains limited due to several key constraints. One significant barrier is the technical complexity and time investment required to develop and customize VM video clips, which discourages direct care staff from implementing this method in practice [46]. As a result, its widespread adoption in employment contexts has been hindered.

Moreover, existing research on VM has predominantly focused on teaching structured work sequences, such as step-by-step vocational tasks, or reinforcing basic social behaviors, such as greeting coworkers or offering assistance [47]. While these applications have proven to be beneficial, they do not adequately address the more complex socio-vocational challenges that individuals with IDD encounter in the workplace, such as resolving conflicts, understanding implicit workplace norms, or managing misunderstandings with employers and colleagues.

A systematic review has further highlighted the absence of VM interventions that incorporate a structured cognitive–behavioral framework to support social problem-solving among individuals with IDD [44]. Although recommendations exist advocating for the integration of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) into interventions for this population [48,49], no prior research has combined VM with SPST to target higher-order socio-vocational skills within employment contexts. This gap underscores the need for interventions that not only teach observable workplace behaviors but also enhance the underlying cognitive and social reasoning processes necessary for long-term vocational success.

We therefore developed and tested PowerMod, a customized, easy-to-use VM app, along with an intervention protocol called Cog ‘n’ Role, which is based on VM and SPST and designed to support the socio-vocational needs of individuals with IDD. This study aimed to address the following research questions:

- To what extent is PowerMod perceived as usable for individuals with IDD?

- To what extent is the Cog ‘n’ Role VM-SPST-based intervention effective for individuals with IDD?

Based on previous literature, we hypothesized the following:

- The VM app and its video clips will be positively regarded by participants with IDD, demonstrating high social validity in terms of relevance, comprehension, and ease of use.

- Cog ‘n’ Role will significantly improve socio-vocational behaviors, as measured by the SVSQ and WPQ.

- Cog ‘n’ Role would contribute to improved employment integration, including transitions from sheltered to supported employment.

2. Phase 1: Social Validity Study

2.1. Social Validity: Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants

A convenience sample was used due to the practical constraints of conducting research within an existing workplace setting. It consisted of 34 participants aged 24 to 67 years (Mdn = 33.5, IQR = 23.5, 43.5). Additional demographic details are presented in Table 1. Participants in the sheltered workshop (n = 24) performed manual tasks requiring fine and gross motor skills, such as sorting, packaging, counting, and assembling products in a controlled setting. Participants in supported employment (n = 10) were employed in various retail and food service environments, holding roles that required self-management and social skills, such as assisting customers, organizing the store, and preparing food while meeting productivity expectations and maintaining high-quality standards. They received individualized support from an employment counselor on a daily or weekly basis, tailored to their specific needs.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study sample.

Twenty-seven participants were diagnosed with mild IDD and seven with moderate IDD, in accordance with the DSM-5 [50]. Participants were selected based on their ability to provide meaningful feedback essential for the usability study. Inclusion criteria focused on individuals who demonstrated basic expressive communication skills, such as the capacity to convey thoughts or preferences, and could articulate their experiences and perceptions related to the intervention. These criteria were aligned with best practices for social validity assessment, which emphasize the importance of including participants who can directly express their opinions on an intervention’s usability and relevance [51]. By ensuring that participants had at least a moderate ability to communicate their experiences, we aimed to obtain meaningful insights into PowerMod’s usability from the perspective of its intended users.

2.1.2. Instruments

Adapted Videos

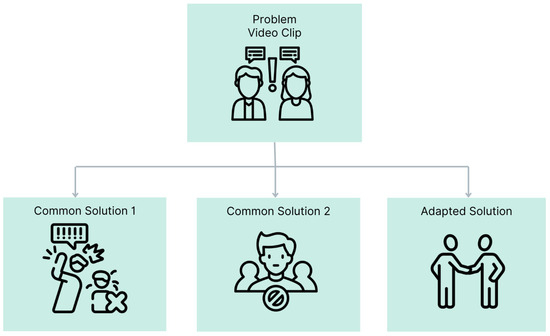

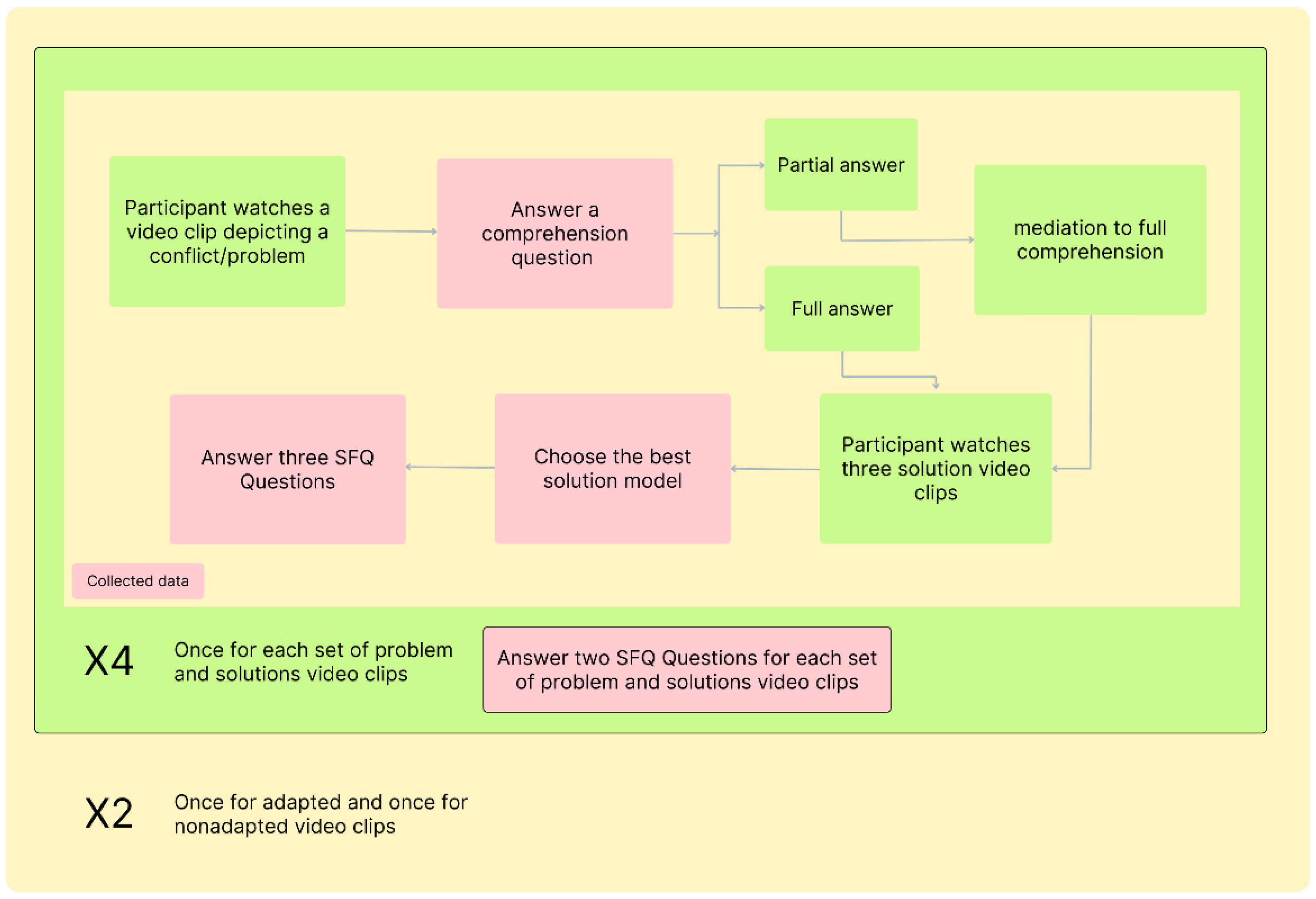

This study used four groups of customized VM scenarios depicting common conflicts in the work environment of people with IDD. Each group included one video clip that presented a social or behavioral “problem” and three video clips showing alternate ways to respond to that conflict; only one of the three video clips depicted adaptive behavior, henceforth referred to as “solutions” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Video modeling scheme.

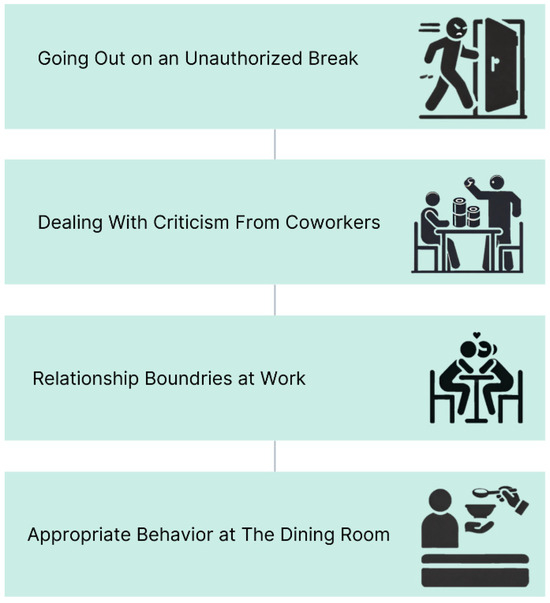

In accordance with [48] recommendation to simplify tools relative to the information processing abilities of people with IDD, the content of the video clips was prepared in consultation with a focus group of eight professionals experienced in working with individuals with IDD. The group included two video modeling specialists and six staff members from sheltered and supported employment programs, comprising managers, coordinators, and counselors. These professionals identified the selected topics as common socio-occupational challenges frequently observed among individuals with IDD in vocational settings. Specifically, they emphasized difficulties such as delaying gratification, coping with mistakes, communicating with employers and colleagues, and self-advocacy as significant barriers to sustained employment for this population. The video clips were then developed based on cognitive-linguistic recommendations for simple language and expressions familiar to people with IDD, including speaking at a suitable pace, filming in a natural and familiar work environment, and reducing visual and cognitive overload [43,52,53]. The topics recorded are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Filmed topics.

PowerMod

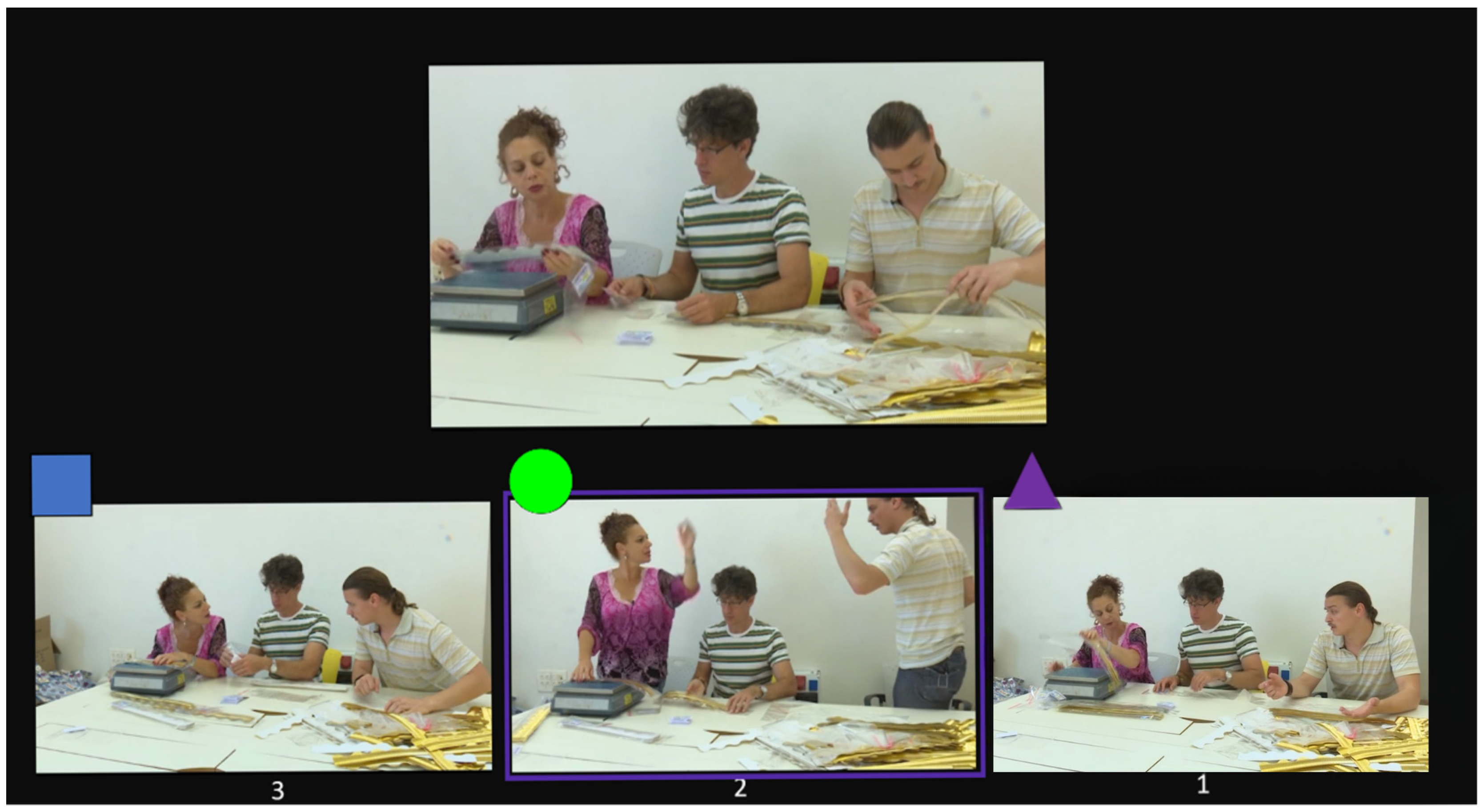

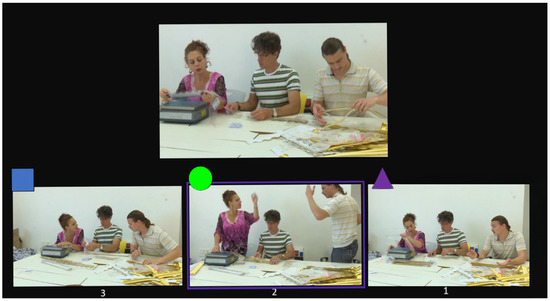

The video scenarios were presented using an interface developed for this study called PowerMod, which runs on Microsoft Office PowerPoint software (version 2016 and up). The interface includes a quick and easy template for building and displaying the video clips while documenting the participants’ choices (Figure 3). PowerMod was designed and programmed based on user trials of several “beta” platforms in a series of autism and IDD studies [38,54].

Figure 3.

PowerMod interface solution slide. Solution models that have already been watched are marked with a purple outline to assist in the choice-making process. The colored shapes on the top-left of each video clip facilitate orientation for participants who are unable to read. Consent has been obtained from all persons shown in the figure.

The template includes a dark background and simple icons adapted for people with IDD based on research and clinical recommendations [53]. Clicking on an image opens the linked video clip and returns viewers to their previous location when it ends. The system is structured to enable participants to view a video clip of a presented social problem, followed by three video clips of possible solutions. Participants choose their preferred response by clicking an icon; their selection is recorded and kept in a secure data repository.

PowerMod was developed to address specific research needs that were not fully met by existing platforms. While conventional video presentation tools allow for the display of video content, they do not typically support structured decision-making processes tailored for individuals with IDD or integrate automated response tracking. PowerMod facilitates the creation of video-based scenarios within an accessible user interface and enables systematic data collection, making it a suitable tool for studies and therapy sessions that require both participant engagement and response documentation.

2.1.3. Measurements

Comprehension Questions

After watching each video clip depicting a social problem, the participants were asked to “Describe what happened in this video” in their own words. These queries were used to confirm that the participants understood the depicted social problem before viewing the solutions. For each video clip, the examiner rated their comprehension level on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (does not know/cannot remember) to 5 (describes all aspects of the situation).

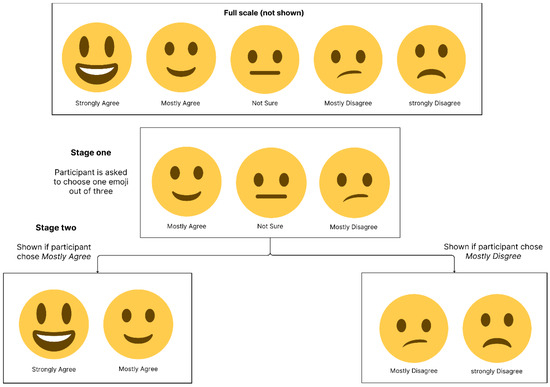

Adapted User Experience Questionnaire

The Short Feedback Questionnaire (SFQ) [55] is a user experience questionnaire that assesses participants’ responses to engaging in virtual tasks or computer games (see Table 2). The SFQ was adapted for participants with IDD and further modified for this study by retaining five items, which were general relevance (“happens in my setting”), ease of viewing, comfort while viewing, enjoyment, and personal relevance (“happens to me”). The original rating scale was adapted to enhance its usability by replacing the original five-point numeric scale with a five-point “smiley scale” (see Appendix A) [56,57]. Total scores ranged from 5 to 25.

Table 2.

Measurement properties.

Non-Adapted Videos

The non-adapted video clips were designed to reflect common solutions to workplace conflicts, as applied by populations with other disabilities (e.g., high-functioning autism and mental health conditions). In contrast, the adapted video clips were specifically tailored to the cognitive and social needs of individuals with IDD, incorporating simplified language, reduced visual complexity, and slower pacing. This distinction allowed us to evaluate whether the adaptations improved comprehension and social validity for the target population.

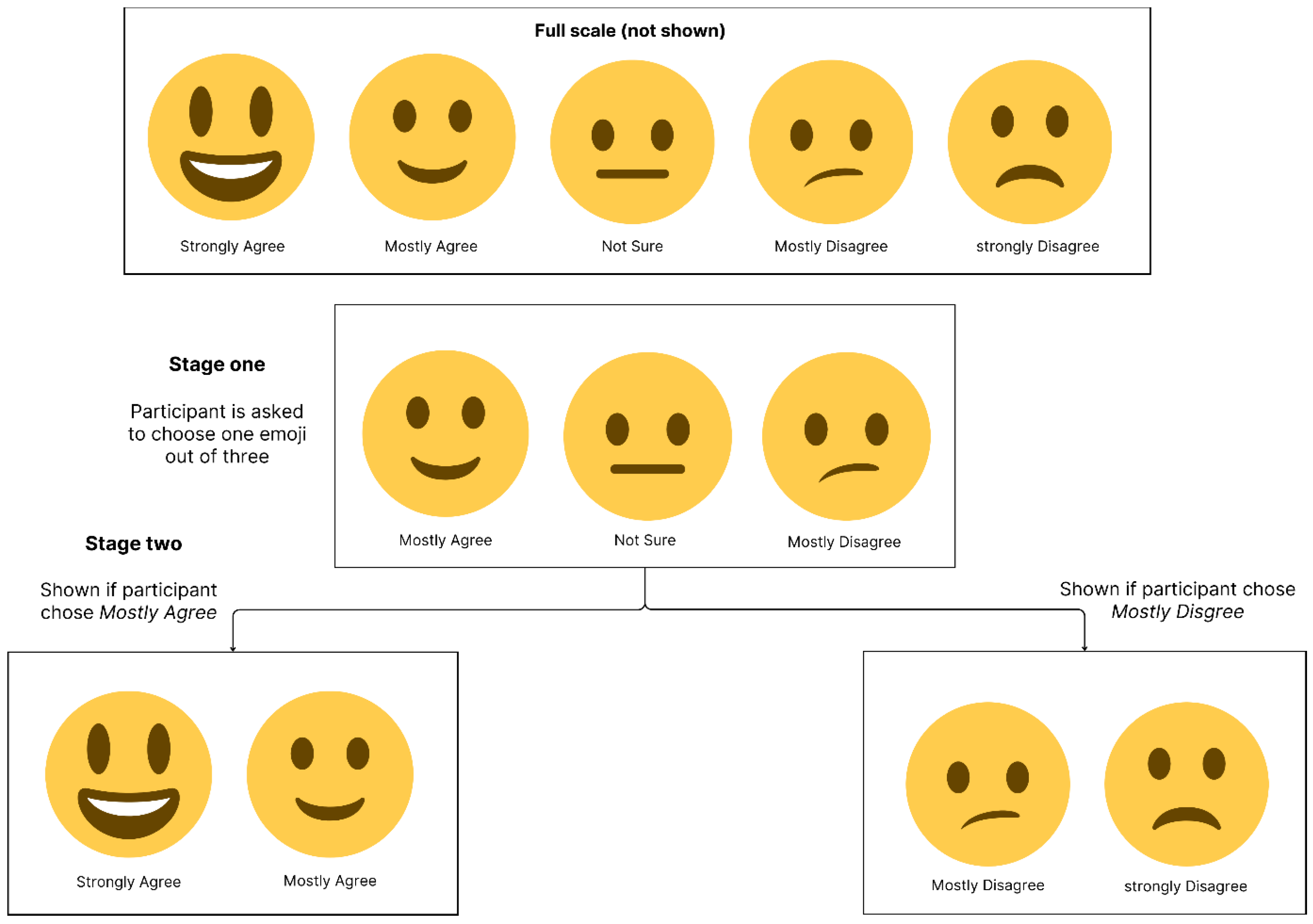

2.1.4. Procedure

Following approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences at the Haifa University (Approval No. 275/16) and the Director of Research at the Israel Ministry of Social Welfare, written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians, along with oral assent from the participants.

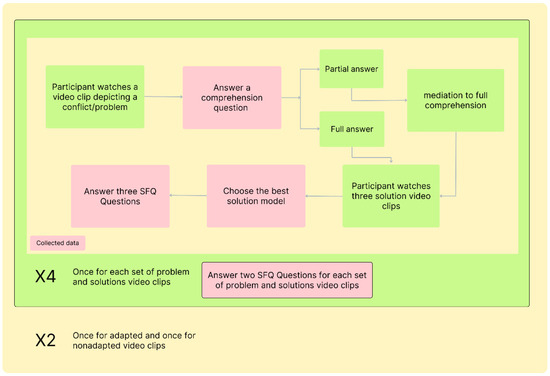

Participants watched a series of both adapted and non-adapted video clips, with each series comprising four sets of video clips focused on different work-related topics. After viewing each problem video clip, participants answered a comprehension question and selected the corresponding solution clip that they believed depicted the main character behaving appropriately. To ensure that all participants had a sufficient understanding of the video content before making their choices, those who provided a partial response to the comprehension question received mediation until full comprehension was reached. This process was applied consistently across all conditions. A detailed breakdown of the intervention process can be found in Appendix B. The SFQ questions were presented at the end of each video clip series. All 34 participants completed the SFQ for both the adapted and non-adapted video clips.

2.2. Social Validity: Data Analysis

The data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (version 29). Cronbach’s alpha was performed to establish the internal consistency of the SFQ and the responses to each comprehension question. Descriptive statistics, including medians and interquartile values, were calculated. Due to the small sample size and non-normal distribution of the data, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used to examine differences between the adapted and non-adapted SFQ and comprehension question ratings. The level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

2.3. Social Validity: Results

Most participants (84.6%) scored 3/5 and above in comprehension of the problem video clips. They could verbally describe what they had viewed, demonstrating their understanding of the situation. However, only 61.8% could correctly select the appropriate solution to the presented problems. The levels of comprehension for the adapted video clips (Mdn = 4.0, IQR = 3.25, 4.31) were significantly higher than those for the non-adapted video clips (Mdn = 3.6, IQR = 3.12, 4.0; Z = −2.36, p < 0.02). The general relevance of the adapted (Mdn = 3.67, IQR= 2.67, 4.54) was reported to be significantly more significant than the non-adapted video clips (Mdn = 2.63, IQR = 2, 3.75; Z = −2.71, p < 0.007). The reported sense of enjoyment, ease of viewing, and comfort were equally high (p = 0.78, p = 0.86, p = 0.95) for both the adapted and non-adapted video clips, with no significant differences between them.

3. Phase 2: Intervention Study

3.1. Intervention Study: Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants

In total, 17 participants with IDD (8 men and 9 women) were selected from the 34 participants of the Phase 1 study (Mdn = 34 years; IQR = 23, 63). Selection was based on the presence of at least one of four identified socio-vocational challenges, as reported by their counselors: difficulty waiting for shared breaks, inappropriate responses when confronted by peers, inappropriate sexual behavior, or behavior that does not align with accepted dining room norms. These behaviors were chosen as inclusion criteria because they represent common socio-vocational challenges among individuals with IDD and are directly addressed by the intervention.

3.1.2. Measurements

Social–Vocational Skills Questionnaire (SVSQ)

The SVSQ was developed specifically for this study to examine how participants coped with specific conflicts portrayed in the video clips. The questionnaire was designed in collaboration with the research supervisors, who have expertise in the field of IDD, to ensure that the statements were formulated in a clear and accessible manner for the target population. It also contained a demographic intro, depicting the participants’ current workplace (sheltered or supported). The 20-item questionnaire was completed by a counselor who was well acquainted with the participant. The items were divided into four topics: waiting for shared breaks, responding appropriately when confronted by peers, appropriate sexual behavior, and behavior while dining with friends. The responses were rated on a 5-item Likert scale, where 5 represents behavior that is always observed, and 1 represents behavior that is never observed.

Work Performance Questionnaire (WPQ) [59]

The WPQ was developed for people with autism and includes five skill areas required for work. Responses are rated on frequency and independence scales and are completed individually by the employee and their direct managers. Steinberger [60] demonstrated an internal reliability of α = 0.82 for the frequency scale and α = 0.87 for the independence scale. The current study used the questionnaire to measure the transfer of learned behaviors into different contexts.

To align with the intervention’s focus on socio-vocational skills, two domains from the WPQ were selected: (a) presentation (appearance at work) and (b) contact/interaction with colleagues and superiors. These domains were chosen because they reflect general workplace social skills, such as awareness of a professional appearance and engaging appropriately with coworkers and supervisors. In contrast to the SVSQ, which assesses specific socio-vocational challenges, these WPQ domains provide a broader evaluation of workplace social competencies

3.1.3. Procedure

Cog ‘n’ Role Intervention

Based on the CBT model, Cog ‘n’ Role is a VM intervention that addresses the socio-vocational skill training needs of people with IDD. It integrates VSM and SPST. A repeated measures design was used [61]. Specifically, outcome measures for each participant were taken at five time points, detailed in Table 3. During Time B (the intervention), participants attended four 45 min one-on-one weekly sessions. Each session addressed a different topic and was conducted according to a structured protocol in which the participant viewed video clips on that topic, experienced guided questioning, recorded role-play scenarios (video-self modeling), and received specific positive feedback for any demonstrated adapted behaviors (detailed in Appendix C). The occupational therapists who provided the intervention received training on how to conduct a flowing and logical session, including simple language, short sentences, and mediation (e.g., participants who gave partial answers could rewatch the video clips with pauses and a short verbal explanation). To ensure consistency in intervention delivery, the facilitators followed a standard protocol and engaged in ongoing discussions with a third researcher to address any procedural questions. This process ensured that any issues raised during the intervention were resolved in a uniform manner across sessions. Notably, the primary researcher who developed the protocol remained blinded to these discussions to prevent bias. In addition, special emphasis was given to reducing the likelihood of participants’ tendency to please the therapist and ensuring that their responses genuinely reflected their opinions, outlined in greater detail within the Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C.

Table 3.

Procedure timeline.

3.2. Intervention Study: Data Analysis

Using SPSS (version 29), we examined employment type changes and whether the participants’ socio-vocational skills improved following the intervention. The non-parametric Wilcoxon test, along with Chi-square, Friedman, and Cochran’s Q tests, was performed to determine differences between measurement time points A1–A2, A2–A3, and A3–A4. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3.3. Intervention Study: Results

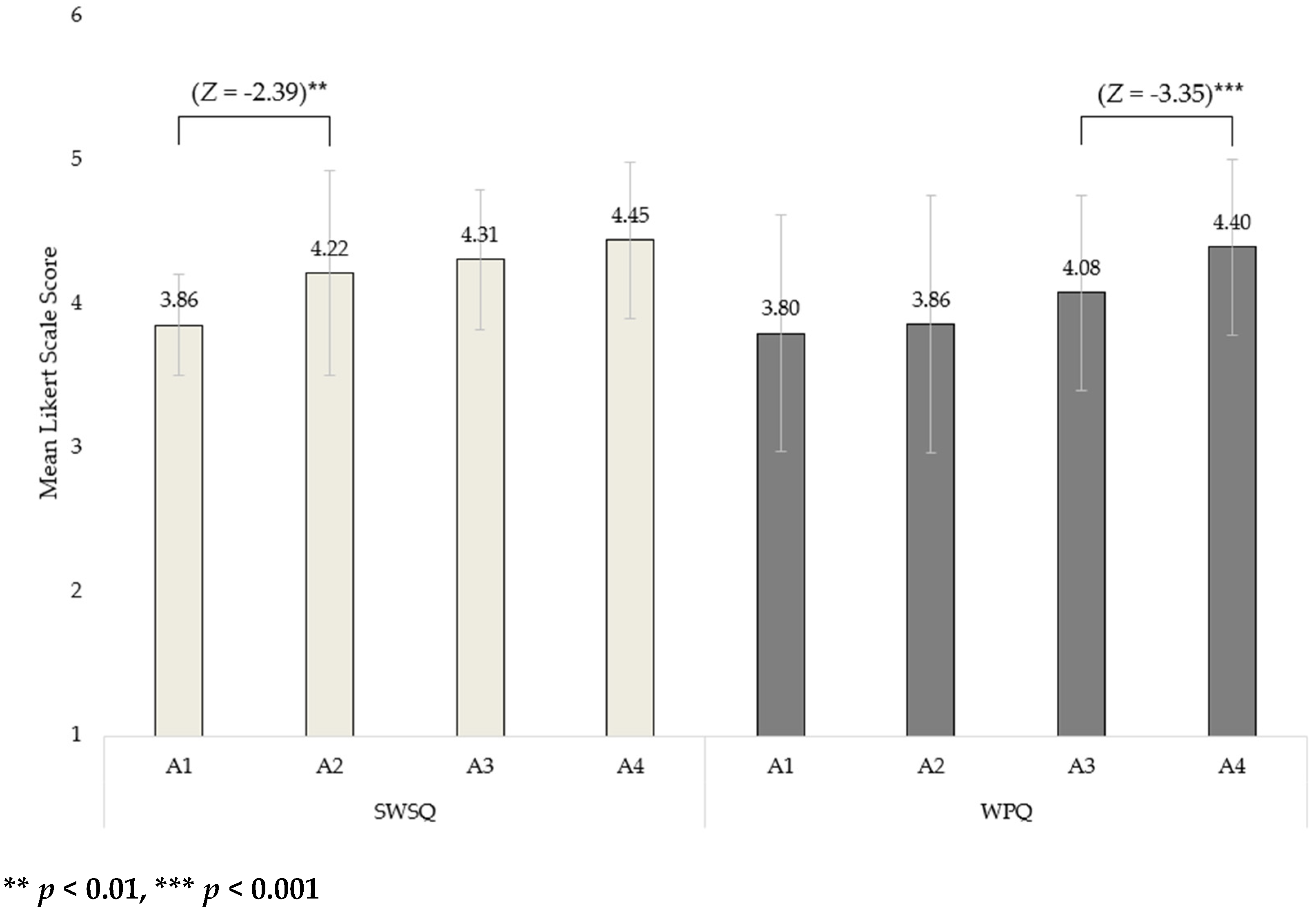

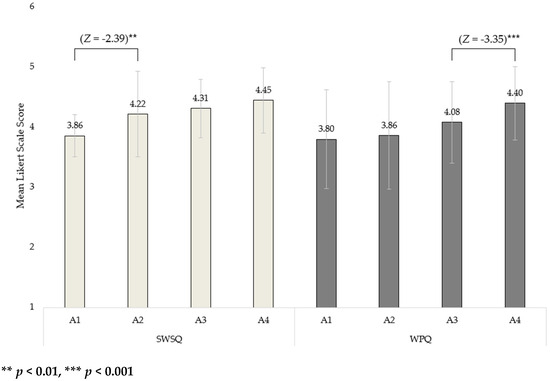

Seventeen participants were initially recruited; however, data from one participant were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires, resulting in a final sample of sixteen participants. Figure 4 shows significantly improved behaviors as measured by the SVSQ between the two pre-intervention time points A1 and A2 (Z = −2.39, p < 0.01), suggesting that only two VM exposures, separated by one month, were sufficient to enhance specific adaptive behaviors. No significant improvement in behavior was measured between time points A2 and A3 (Z = −0.68, p < 0.49), indicating that there was no further improvement in adaptive behaviors immediately after the intervention. However, between A2 and A3, the percentage of participants selecting non-adaptive solutions (e.g., the main character in the video clip leaving the work site for an unauthorized break) decreased from 31% to 16%. Friedman’s test revealed marginal differences in adaptive solutions, χ² (3, N = 16) = 7.57, p = 0.056, Kendall’s W = 0.16. Although the statistical significance was marginal, a post hoc analysis using Rosenthal’s formula [62] indicated a moderate effect size (Z = −1.87, p = 0.06, r = 0.46), suggesting a marginally significant but clinically meaningful reduction in non-adaptive responses.

Figure 4.

Differences in the SVSQ and WPQ measures between time points as measured using the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test. Bars represent means with standard deviations (SDs).

Significant improvement in behavior was observed on the WPQ between A3 and A4 (Z = −3.35, p < 0.001), reflecting a general improvement in socio-vocational skills one month after the intervention ended. Additionally, a significant change in employment type was observed (Cochran Q = 24.4, p = 0.001). Subsequent analysis using the McNemar test pinpointed that these changes occurred specifically between A3 and A4, with six of the seventeen participants (35%) transitioning to supported employment at follow-up (p = 0.031). A substantial effect size (Φ = 2.04) highlighted a meaningful shift in employment patterns during this period.

4. Discussion

This pilot study investigated the social validation and effectiveness of a video modeling application and intervention specifically tailored to enhance the socio-vocational skills crucial for securing and maintaining the employment participation of people with IDD. The results provide experimental support that a cognitively adapted and accessible VM app facilitates a user-friendly experience. This is also supported by a growing body of research that supports the notion that individuals with IDD can offer reliable and valid feedback on practical issues when presented with cognitively accessible tools.

For instance, studies underscore that technological innovations, such as cognitively accessible software on tablets, foster greater independence, accuracy, and efficiency, allowing individuals with varying intellectual capacities to respond autonomously to surveys compared to conventional methods [63,64,65]. Furthermore, collaborative research efforts and inclusive design strategies, such as simplified language and visual augmentations, enhance the feasibility and reliability of self-report measures for this population [66]. These affirm that with appropriate adaptations, people with IDD can actively and meaningfully engage in tailoring and improving the resources and services designed to support their needs.

Previous studies involving people with IDD have highlighted the necessity of assessing not only the enjoyment and usability of technology-based interventions but also their cognitive appropriateness [67,68]. They have also demonstrated that measuring the participant’s comprehension of a tested task is an important component of determining an intervention’s overall effectiveness [69,70]. Comprehension is particularly critical for social validity, as participants are more likely to perceive an intervention as acceptable, relevant, and meaningful if they can understand its content and purpose. In the current study, the significantly higher comprehension levels for the adapted video clips (Mdn = 4.0 vs. Mdn = 3.6 for non-adapted video clips; p < 0.02) suggest that the tailored adaptations not only improved understanding but also enhanced the social validity of the intervention itself. Ensuring that participants understand assessment and intervention materials and how to use them is likely an essential first step for meaningful learning and skill acquisition [68].

The availability of simple tools to support intervention is another critical consideration for technology-based interventions. Research in this field indicates that professional staff need to invest excessive amounts of time and resources when developing VM video clips or working on their session plans, and that this can lead to reluctance to use technology-based interventions [46,71]. By streamlining the process, simple-to-use apps such as PowerMod may address this challenge, enabling more efficient implementation of VM in care centers for individuals with IDD and reducing the barriers associated with technology-based interventions. The long-term impact of integrating such tools into professional settings is also noteworthy. In a follow-up survey conducted one year after PowerMod was introduced in sheltered employment facilities, professional and direct staff reported high confidence in using the online version, which included both structured presentations and a user guide [72]. These findings suggest that providing accessible and structured technological solutions can facilitate sustained adoption and integration of VM-based interventions in vocational environments for individuals with IDD.

The results of Phase 2 demonstrated significant improvements in specific social and vocational functioning among most participants at their workplaces following just two pre-intervention exposures to the VM video clips (A1 versus A2). This finding indicates that the primary impact of the VM video clips facilitated awareness of nonadaptive behaviors and enabled skill enhancements. Similar results have been shown in other VM studies that emphasize the power of even minimal exposure as a key component in their methodologies [73,74,75].

Although immediate post-intervention outcomes did not show additional significant changes in behavior, participants were able to identify more adaptive solutions by the end of the intervention. This pattern suggests that while early exposures (A1–A2) were sufficient to raise awareness and initiate behavioral adjustments, additional exposures (A2–A3) did not immediately lead to further measurable changes in real-life situations, possibly due to the need for real-world application and reinforcement of these skills over time. These findings align with meta-analytical data on CBT interventions for individuals with IDD, which indicate that adaptive behaviors often require a more extended period to consolidate and generalize into real-life contexts [49]. Research has shown that behavioral and cognitive changes in this population tend to emerge progressively, with significant improvements frequently observed only in later follow-up assessments, sometimes months after the intervention’s completion [49]. Nevertheless, the selection rate for the adaptive solution video clips did increase significantly at A3, indicating that when participants were exposed to the video clips and asked to choose the best solution to the problem in their opinion, they made more informed choices. Most importantly, a general improvement in socio-vocational behaviors was noted one month after the intervention concluded, which could be explained by a covert learning process.

This improvement, documented via the WPQ, suggests a transfer of the learned behaviors into various socio-vocational contexts, including accuracy, responsibility, appearance, and relationships with the employer and colleagues. Such findings align with studies demonstrating continued learning and skill generalization in individuals with IDD beyond immediate post-intervention testing. For instance, O’Reilly et al. [76] reported that social skills training based on SPST resulted in a better outcome in the generalization tests than during the intervention itself, and up to four weeks post-intervention. Similarly, a VM program study [18] found further significant improvements in social behaviors during follow-up periods.

Furthermore, MacFarland et al. [77] found significant improvements in social skills across diverse contexts, even weeks after the initial training. This pattern of spontaneous learning post-intervention in these studies clarifies the improvement observed in the WPQ between the immediate post-intervention assessment (A3) and follow-up (A4). It suggests that individuals with IDD may exhibit unique learning trajectories, where the consolidation and application of skills extend beyond the structured training environment and are manifested more prominently during real-life application [78].

An important result showed that six of the seventeen participants transitioned to supported employment at follow-up. Although this shift suggests a potential positive impact of the intervention, it is important to acknowledge that other external factors may have also contributed to employment transitions. These changes were assessed based on reports from direct counselors, who documented any transitions from sheltered to supported employment. Given that this study did not include a control group, causal claims should be made with caution.

Despite these limitations, documenting actual employment transitions is particularly valuable, as field studies typically focus on reporting improved employment opportunities or the desired transition from the education system to employment, rather than concrete job placements [79,80]. Thus, our findings highlight the need for further research to systematically examine the factors influencing employment transitions in individuals with IDD.

5. Conclusions

This feasibility study highlights the potential of video modeling interventions, delivered through an accessible and user-friendly application, to enhance the socio-vocational skills of individuals with IDD. The findings demonstrate that with minimal exposure to cognitively adapted video clips, participants not only developed awareness of nonadaptive behaviors but also achieved a learning experience of desired skills. Improvements observed one-month post-intervention suggest that the learned behaviors were effectively transferred across diverse workplace contexts. These results underline the importance of combining a socially valid user-centered tool like PowerMod with a tailored intervention such as Cog ‘n’ Role. Furthermore, the transition of several participants to supported employment reinforces the value of interventions aimed at fostering inclusion, vocational independence, and success for people with IDD.

6. Limitations

While the convenience sampling method facilitated smoother access and higher engagement, it also limits the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should aim to replicate these results with more diverse and randomly selected samples to strengthen external validity. Furthermore, we recommend the inclusion of other socio-vocational skills beyond the four recorded for this study (e.g., managing a conversation with a colleague or the importance of teamwork and personal space).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.P., Y.B.R., S.Z., P.L.W. and E.G.; methodology, writing and editing, Y.B.R., S.Z., P.L.W. and E.G.; investigation and software, Y.B.R.; project administration, supervision, and funding acquisition, P.L.W. and E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Shalem Fund, grant number 181.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences at the Haifa University (Approval No. 275/16; approved on 17 May 2016) and the Director of Research at the Israel Ministry of Social Welfare.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians, along with oral assent from the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request. Video clips and additional information are available at https://videomodeling.kshalem.org.il/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Elwyn Israel association and Tami Martin for giving us the opportunity to conduct the intervention within their sheltered workshop with excellent cooperation and endless grace. We also thank Sandra Zukerman for her excellent statistical counseling and Rachel Kizony for her guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Smiley Scale

Figure A1.

Demonstration of the stages of answering the SFQ using field reduction.

Figure A1.

Demonstration of the stages of answering the SFQ using field reduction.

Appendix B. Social Validity Procedure

Participants with IDD were scheduled for individual meetings in quiet rooms with computers for a period of 30–40 min. They had the option of using headphones or external speakers while viewing adapted and non-adapted video clips. A comprehension question at the end of each problem video was used, with personalized mediation provided to those experiencing difficulty. Mediation included previewing instructions, such as “pay attention to their conversation and body language”, and guided questions such as “What did character X ask character Y?”. Three solution video clips in a randomized order were then presented, depicting different ways of responding to a challenging situation, with one showing adaptive behavior and the other two showing common inappropriate behaviors. Participants selected a response video in which they perceived the main character to act appropriately, and the selection was documented using PowerMod. The SFQ questions were presented in two stages: three questions at the end of each set of video clips (one problem scenario + three responses) and two additional questions at the end of all adapted video clips as well as at the end of all non-adapted video clips.

Figure A2.

Depiction of the social validity protocol.

Figure A2.

Depiction of the social validity protocol.

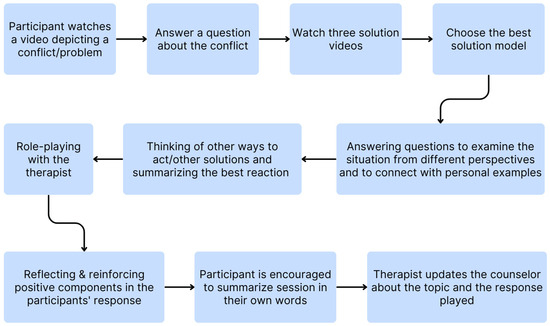

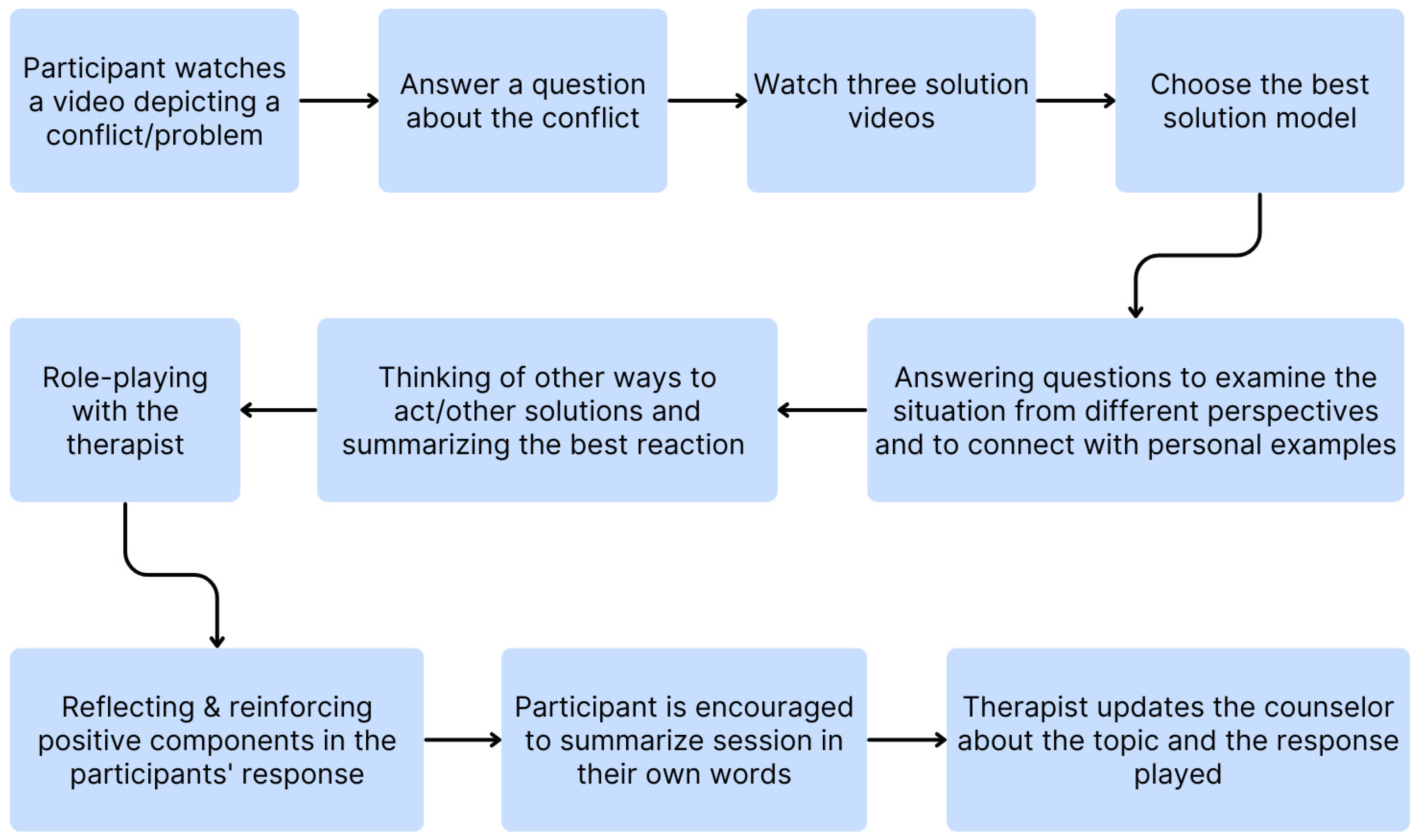

Appendix C. Cog ‘n’ Role Intervention Session Protocol

An illustration follows the text. Initially, the participant watched a video that showed a social problem. They were asked to explain what happened in the video and whether it was acceptable in the workplace. Next, they watched three solution video clips (only one showed an adapted solution) and chose the one that showed the most appropriate solution in their opinion. The participant was asked to analyze the situation from each video character’s perspective and emotions, think of additional solutions, and describe their or their colleagues’ behaviors in these situations. In the next stage, the participant was encouraged to think about appropriate responses to the problem shown. The examiner filmed herself and the participant role-playing (VSM) a chosen response. Then, the participant watched their video and was asked to express an opinion or comment on what they saw. The examiner not only reinforced the adapted behaviors the participant performed but also provided positive feedback, creating a supportive and encouraging environment. To help assimilate the principles learned from the session, a recall exercise was conducted at the end of each session to prevent short-term memory deficits [48,81,82]. Finally, to facilitate new behaviors, the participants’ counselors were updated on the topics and selected responses after each session. However, to avoid bias in the counselors’ responses to the study’s questionnaires, the counselors were not present at the intervention sessions.

Figure A3.

Illustration of the different stages of the protocol.

Figure A3.

Illustration of the different stages of the protocol.

References

- Gilson, C.B.; Carter, E.W.; Bumble, J.L.; McMillan, E.D. Family Perspectives on Integrated Employment for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2018, 43, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, S.; Nota, L.; Ginevra, M.C.; Soresi, S. Career Adaptability, Hope and Life Satisfaction in Workers with Intellectual Disability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsor, J.; Timmons, J.; Butterworth, J.; Migliore, A.; Domin, D.; Zalewska, A.; Shepard, J. StateData: The National Report on Employment Services and Outcomes Through 2018. 2021. Available online: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/ici_pubs/132/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Davies, A.; Fidler, D.; Gorbis, M. Future work skills 2020. Univ. Phoenix Res. Inst. 2011, p. 19. Available online: https://legacy.iftf.org/uploads/media/SR-1382A_UPRI_future_work_skills_sm.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Dean, S.A.; East, J.I. Soft Skills Needed for the 21st-Century Workforce. Int. J. Appl. Manag. Technol. 2019, 18, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.E. Skills for the 21st Century: A Meta-Synthesis of Soft-Skills and Achievement. Can. J. Career Dev. 2018, 17, 73–86. Available online: https://cjcd-rcdc.ceric.ca/index.php/cjcd/article/view/80 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Harris, J.C.; Greenspan, S. Definition and nature of intellectual disability. In Handbook of Evidence-Based Practices in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilitiesy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, B.; Kearney, K.B.; Brady, M.P.; Downey, A.; Torres, A. Teaching Small Talk: Increasing On-Topic Conversational Exchanges in College Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Using Remote Audio Coaching. Behav. Modif. 2021, 45, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader-Grosbois, N.; Houssa, M.; Mazzone, S. How could Theory of Mind contribute to the differentiation of social adjustment profiles of children with externalizing behavior disorders and children with intellectual disabilities? Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 2642–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolli, A.; Ricci, M.C.; Cerciello, F.; Ciotola, S.; Esposito, C.; Rega, A. The Importance of Mentalization Skills for Job Success. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2022, 3265. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3265/paper_6167.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- van den Akker, N.; Kroezen, M.; Wieland, J.; Pasma, A.; Wolkorte, R. Behavioural, psychiatric and psychosocial factors associated with aggressive behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and narrative analysis. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 327–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathje, M.; Schrier, M.; Williams, K.; Olson, L. The lived experience of sexuality among adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A scoping review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 75, 7504180070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Martín, J.; Simó-Pinatella, D.; Font-Roura, J. Assessment of Challenging Behavior Exhibited by People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinney, G.; Forde, J.; Hone, L.; Flanagan, L.; Smith, M. Safe and social: What does it mean anyway? Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2014, 43, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, K.M.; Mechling, L.; Sansosti, F.J.; Hall, A. The Use of Mobile Technologies to Assist with Life Skills/Independence of Students with Moderate/Severe Intellectual Disability and/or Autism Spectrum Disorders: Considerations for the Future of School Psychology. Psychol. Sch. 2013, 50, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, B.; Melekoğlu, M.A. Determination of employment-related social skills in the service sector for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 71, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, K.A.; Radley, K.C.; Schrieber, S.R.; Derieux, J.R. Vocational Social Skills Training for Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Pilot Study. J. Behav. Educ. 2023, 32, 212–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Handley, R.D.; Ford, W.B.; Radley, K.C.; Helbig, K.A.; Wimberly, J.K. Social Skills Training for Adolescents With Intellectual Disabilities: A School-Based Evaluation. Behav. Modif. 2016, 40, 541–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezu, A.M.; Nezu, C.M.; Gerber, H.R.; Damico, J.L. Emotion-Centered Problem-Solving Therapy. Compr. Clin. Psychol. Second Ed. 2022, 6, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevala, N.; Pehkonen, I.; Teittinen, A.; Vesala, H.T.; Pörtfors, P.; Anttila, H. The Effectiveness of Rehabilitation Interventions on the Employment and Functioning of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2019, 29, 773–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkas, M. Sheltered or Supported Employment Options for Secondary Education Students with Disabilities? IJASOS—Int. E—J. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2022, VIII, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalky, H.A. Employment outcomes for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A literature review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 109, 104656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.L.; Wheeler, J.J. Social Validity in Health Sciences. In The Social Validity Manual—Subjective Evaluation of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Chapter 10; pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger, A.; Barahona, C.; Cavalari, R.N.S.; Parent, V.; Luiselli, J.K.; DuBard, M. Social Validity Assessment of Job Satisfaction, Resources, and Support Among Educational Service Practitioners for Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2014, 26, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiselli, J.K. Social validity assessment. In Organizational Behavior Management Approaches for Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, M.L.; Shogren, K.A. Self-Determination and Choice. In Handbook of Evidence-Based Practices in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Singh, N.N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 561–584. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, C.; Tekin-Iftar, E.; Yikmis, A. Effects of Mother-Delivered Social Stories and Video Modeling in Teaching Social Skills to Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Spec. Educ. 2017, 50, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J.M. Using mixed methods to establish the social validity of a self-report assessment: An illustration using the Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA). J. Mix. Methods Res. 2011, 5, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, F.; de Boer, A.; Kupers, E.; Minnaert, A. It also takes teachers to tango: Using social validity assessment to refine an intervention design. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 107, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Menlove, F.L. Factors determining vicarious extinction of avoidance behavior through symbolic modeling. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bross, L.A.; Travers, J.C.; Huffman, J.M.; Davis, J.L.; Mason, R.A. A Meta-Analysis of Video Modeling Interventions to Enhance Job Skills of Autistic Adolescents and Adults. Autism Adulthood 2021, 3, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauminger-Zviely, N.; Eden, S.; Zancanaro, M.; Weiss, P.L.; Gal, E. Increasing social engagement in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder using collaborative technologies in the school environment. Autism 2013, 17, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, R.; Wilbanks, S.; Greif, A.; Bonk, S. Effects of a video modeling intervention to improve hand washing independence in children with disabilities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 105, e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olçay Gül, S. The Combined Use of Video Modeling and Social Stories in Teaching Social Skills for Individuals with Intellectual Disability. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2016, 16, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preas, E.; Carroll, R.A.; Van Den Elzen, G.; Halbur, M.; Harper, M. Evaluating the Use of Video Modeling With Voiceover Instructions to Train Therapists to Deliver Caregiver Training Through Telehealth. Behav. Modif. 2023, 47, 402–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubova, G.; Chen, B.B.; Al-Dubayan, M.N.; Gupta, S. Virtual Instruction in Teaching Mathematics to Autistic Students: Effects of Video Modeling, Virtual Manipulatives, and Mathematical Games. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2024, 39, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buggey, T.; Ogle, L. Video self-modeling. Psychol. Sch. 2012, 49, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Weiss, P.L.; Zancanaro, M.; Gal, E. Usability of a video modeling computer application for the vocational training of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 80, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezu, A.M.; Nezu, C.M.; Gerber, H.R. (Emotion-centered) problem-solving therapy: An update. Aust. Psychol. 2019, 54, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, A.J.; McWhirter, L. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Principles, Science, and Patient Selection in Neurology. Semin. Neurol. 2022, 42, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezu, A.M.; Nezu, C.M.; D’Zurilla, T. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Treatment Manual; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu, A.M.; Nezu, C.M. Emotion-Centered Problem-Solving Therapy. In Handbook of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Overview and Approaches; Wenzel, A., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 465–491. [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeyer, M.L.; Shogren, K.A.; Singh, N.N.; Uyanik, H. Strengths-Based Approaches to Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Brock, M.E. Systematic Review of Video-Based Instruction to Teach Employment Skills to Secondary Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2023, 38, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailey, S.H.; Miller, A.M.; Fogg, L. Social Problem Solving in Staffed Community Homes Among Individuals With Intellectual Disabilities and Their Staff. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, 7, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mois, G.; Lydon, E.A.; Mathias, V.F.; Jones, S.E.; Mudar, R.A.; Rogers, W.A. Best practices for implementing a technology-based intervention protocol: Participant and researcher considerations. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 122, 105373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Bouck, E.C.; Duenas, A. Using Video Modeling to Teach Social Skills for Employment to Youth With Intellectual Disability. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2020, 43, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, P.; Lindsay, W. Cognitive behavioral therapy. In Handbook of Evidence-Based Practices in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Singh, N.N., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Chapter 11; pp. 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Graser, J.; Göken, J.; Lyons, N.; Ostermann, T.; Michalak, J. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adults With Intellectual Disabilities: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2022, 29, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 0-89042-555-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.M.; Bird, F.L.; Maguire, H.; Luiselli, J.K. Organizational Behavior Management Approaches for Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781000430707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitpierre, G.; Tabin, M. From Social Vulnerability Assessment to Active Prevention Measures: A Decision-Making Perspective. In Decision Making by Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Integrating Research into Practice; Khemka, I., Hickson, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 469–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K. Towards a universal cognitive tool: Designing accessible visualization for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. ACM SIGACCESS Access. Comput. 2021, 131, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochhauser, M.; Weiss, P.L.; Gal, E. Enhancing conflict negotiation strategies of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder using video modeling. Assist. Technol. 2018, 30, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, P.L.; Bialik, P.; Kizony, R. Virtual Reality Provides Leisure Time Opportunities for Young Adults with Physical and Intellectual Disabilities. CyberPsychology Behav. 2003, 6, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Broghammer-Escher, S.; Baumann, K.; Surzykiewicz, J. Aspects of Spirituality and Life Satisfaction in Persons With Down Syndrome. J. Disabil. Relig. 2017, 21, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlot-van Anrooij, K.; Hilgenkamp, T.I.M.; Leusink, G.L.; van der Cruijsen, A.; Jansen, H.; Naaldenberg, J.; van der Velden, K. Improving Environmental Capacities for Health Promotion in Support Settings for People with Intellectual Disabilities: Inclusive Design of the DIHASID Tool. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, D.; Kizony, R.; Weiss, P.T.L. The Sony PlayStation II Eye Toy: Low-Cost Virtual Reality for Use in Rehabilitation. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2008, 32, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisman-Nitzan, M.; Schreuer, N.; Gal, E. Person, environment, and occupation characteristics: What predicts work performance of employees with autism? Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 78, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, M. Work Performance Questionnaire (WPQ) Questionnaire for a Functioning System in the Work of Employees with ASD: Establishing Reliability and Validity. ProQuest. 2019. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/work-performance-questionnaire-wpq-שאלון-להערכת/docview/2590017628/se-2 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Verma, J.P. Analysis of Variance and Repeated Measures Design. In Repeated Measures Design for Empirical Researchers; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Newark, NJ, USA, 2015; Chapter 2; ISBN 9781119052500. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ariel-ebooks/detail.action?docID=7104382 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Rosenthal, R.; Cooper, H.; Hedges, L. Parametric measures of effect size. Handb. Res. Synth. 1994, 621, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, D.K.; Stock, S.E.; King, L.; Wehmeyer, M.L.; Shogren, K.A. An Accessible Testing, Learning and Assessment System for People with Intellectual Disability. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 63, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.A.; Bacon, A.; O’Hara, D.; Davies, D.; Stock, S.; Brown, C. Using Cognitively Accessible Survey Software on a Tablet Computer to Promote Self-Determination among People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Développement Hum. Handicap Chang. Soc. 2015, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.; Krahn, G.L.; Buck, A.; Andridge, R.; Lecavalier, L.; Hollway, J.A.; Davies, D.K.; Arnold, L.E.; Havercamp, S.M. Putting “ME” into measurement: Adapting self-report health measures for use with individuals with intellectual disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 128, 104298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T. Inclusive Methods for Engaging People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in Research Practices; American Institutes for Research: Arlington, VA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://ktdrr.org/products/info-briefs/KTDRR-EngagingPeopleWithIDD-508.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Dekelver, J.; Daems, J.; Solberg, S.; Bosch, N.; Van de Perre, L.; De Vliegher, A. Viamigo: A digital travel assistant for people with intellectual disabilities: Modeling and design using contemporary intelligent technologies as a support for independent traveling of people with intellectual disabilities. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications (IISA), Corfu, Greece, 6–8 July 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, K.A.; Bonardi, A.; Cobranchi, C.; Krahn, G.; Murray, A.; Robinson, A.; Havercamp, S.M.; Andridge, R.; Arnold, L.E.; Barnhill, J.; et al. State of the Field: The Need for Self-Report Measures of Health and Quality of Life for People With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 18, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evmenova, A.S.; Behrmann, M.M.; Mastropieri, M.A.; Baker, P.H.; Graff, H.J. Effects of Video Adaptations on Comprehension of Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2011, 26, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.J.; Kelley, K.R.; Raxter, A. Effects of PEERS® Social Skills Training on Young Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities During College. Behav. Modif. 2021, 45, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, K.P. Incorporating Video Modeling into a School-Based Intervention for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 2013, 44, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Refael, Y.; Shidlovsky Press, Y. The Implementation Process of a Novel Evidence-Based Integrated Video Modeling Intervention to Improve the Social-Vocational Skills of People with Developmental Disabilities. Isr. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 2, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Bouck, E.; Duenas, A. The Effect of Video Modeling and Video Prompting Interventions on Individuals With Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2019, 34, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, L.A.; Travers, J.C.; Munandar, V.D.; Morningstar, M. Video Modeling to Improve Customer Service Skills of an Employed Young Adult With Autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2019, 34, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munandar, V.D.; Bross, L.A.; Zimmerman, K.N.; Morningstar, M.E. Video-Based Intervention to Improve Storytelling Ability in Job Interviews for College Students With Autism. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2021, 44, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.F.; Lancioni, G.E.; Sigafoos, J.; O’Donoghue, D.; Lacey, C.; Edrisinha, C. Teaching social skills to adults with intellectual disabilities: A comparison of external control and problem-solving interventions. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2004, 25, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarland, M.C.; Fisher, M.H. Peer-Mediated Social Skill Generalization for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability. Exceptionality 2021, 29, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffran, J.R. Statistical learning as a window into developmental disabilities. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2018, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Readhead, A.; Owen, F. Employment Supports and Outcomes for Persons with Intellectual and/or Developmental Disabilities: A Review of Recent Findings. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2020, 7, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giummarra, M.J.; Randjelovic, I.; O’Brien, L. Interventions for social and community participation for adults with intellectual disability, psychosocial disability or on the autism spectrum: An umbrella systematic review. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2022, 3, 935473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.L.; Meunier, J.; Peacock, G. Voices from the Field “Include Me”: Implementing Inclusive and Accessible Communication in Public Health. Assist. Technol. Outcomes Benefits 2022, 16, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ptomey, L.T.; Sullivan, D.K.; Lee, J.; Goetz, J.R.; Gibson, C.; Donnelly, J.E. The Use of Technology for Delivering a Weight Loss Program for Adolescents with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).