Long Working Hours and Unhealthy Lifestyles of Workers: A Protocol for a Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

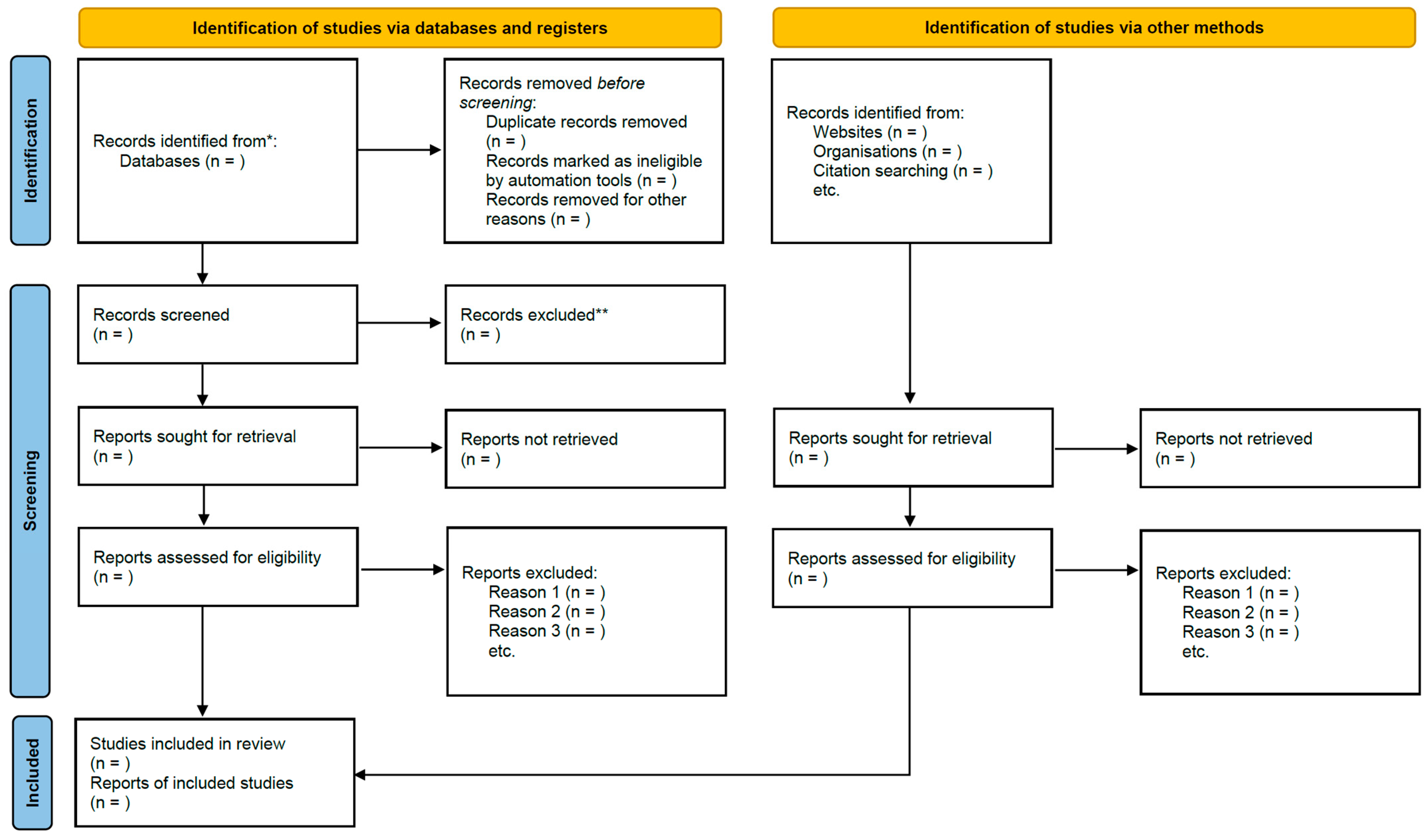

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Concept

2.1.3. Context

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Analysis and Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pega, F.; Nafradi, B.; Momen, N.C.; Ujita, Y.; Streicher, K.N.; Pruss-Ustun, A.M.; Technical Advisory, G.; Descatha, A.; Driscoll, T.; Fischer, F.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000–2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2021, 154, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi, A. Preventing overwork-related deaths and disorders-needs of continuous and multi-faceted efforts. J. Occup. Health 2019, 61, 265–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, Y. Decrease in Weekly Working Hours of Korean Workers from 2010 to 2020 According to Employment Status and Industrial Sector. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Min, J. Working hours and the regulations in Korea. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 35, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervasti, J.; Pentti, J.; Nyberg, S.T.; Shipley, M.J.; Leineweber, C.; Sorensen, J.K.; Alfredsson, L.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; et al. Long working hours and risk of 50 health conditions and mortality outcomes: A multicohort study in four European countries. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 11, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Jokela, M.; Madsen, I.E.; Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Lallukka, T.; Nyberg, S.T.; Alfredsson, L.; Batty, G.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; et al. Long working hours and depressive symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies and unpublished individual participant data. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2018, 44, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descatha, A.; Sembajwe, G.; Pega, F.; Ujita, Y.; Baer, M.; Boccuni, F.; Di Tecco, C.; Duret, C.; Evanoff, B.A.; Gagliardi, D.; et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pega, F.; Ujita, Y.; Brisson, C.; Clays, E.; Descatha, A.; Ferrario, M.M.; Godderis, L.; Iavicoli, S.; Landsbergis, P.A.; et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on ischaemic heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaki, M.; Jokela, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Fransson, E.I.; Alfredsson, L.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; Casini, A.; et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. Lancet 2015, 386, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.Y.; Park, H.; Seo, J.C.; Kim, D.; Lim, Y.H.; Lim, S.; Cho, S.H.; Hong, Y.C. Long working hours and cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 54, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, A.; Denison, H.J.; Corbin, M.; Barnes, L.; ’t Mannetje, A.; McLean, D.; Jackson, R.; Laird, I.; Douwes, J. Long working hours, sedentary work, noise, night shifts and risk of ischaemic heart disease. Heart 2023, 109, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadel, M.; Li, J.; Sembajwe, G.; Gagliardi, D.; Pico, F.; Ozguler, A.; Evanoff, B.A.; Baer, M.; Tsutsumi, A.; Iavicoli, S.; et al. Cumulative Exposure to Long Working Hours and Occurrence of Ischemic Heart Disease: Evidence from the CONSTANCES Cohort at Inception. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loef, M.; Walach, H. The combined effects of healthy lifestyle behaviors on all cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colpani, V.; Baena, C.P.; Jaspers, L.; van Dijk, G.M.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Dhana, K.; Tielemans, M.J.; Voortman, T.; Freak-Poli, R.; Veloso, G.G.V.; et al. Lifestyle factors, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Pan, X.F.; Chen, J.; Cao, A.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Pan, A. Combined lifestyle factors, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, S.; Neuenschwander, M.; Ballon, A.; Nothlings, U.; Barbaresko, J. Adherence to healthy lifestyles and incidence of diabetes and mortality among individuals with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Allen, N.B.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Black, T.; Brewer, L.C.; Foraker, R.E.; Grandner, M.A.; Lavretsky, H.; Perak, A.M.; Sharma, G.; et al. Life’s Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association’s Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, e18–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Jokela, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Madsen, I.E.; Lallukka, T.; Ahola, K.; Alfredsson, L.; Batty, G.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; et al. Long working hours and alcohol use: Systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies and unpublished individual participant data. BMJ 2015, 350, g7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bully, P.; Sanchez, A.; Zabaleta-del-Olmo, E.; Pombo, H.; Grandes, G. Evidence from interventions based on theoretical models for lifestyle modification (physical activity, diet, alcohol and tobacco use) in primary care settings: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2015, 76, S76–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, X.; Wei, L.; Yang, K.; Jiao, M. The impact of high-risk lifestyle factors on all-cause mortality in the US non-communicable disease population. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, H.; Xu, F.; Qin, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, D.; Jia, S.; Zhang, Q. Combined lifestyle factors on mortality among the elder population: Evidence from a Chinese cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugulies, R.; Sorensen, K.; Di Tecco, C.; Bonafede, M.; Rondinone, B.M.; Ahn, S.; Ando, E.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Cabello, M.; Descatha, A.; et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2021, 155, 106629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Masuya, J.; Hashimoto, S.; Honyashiki, M.; Ono, M.; Tamada, Y.; Fujimura, Y.; Inoue, T.; Shimura, A. Long Working Hours Indirectly Affect Psychosomatic Stress Responses via Complete Mediation by Irregular Mealtimes and Shortened Sleep Duration: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escoto, K.H.; Laska, M.N.; Larson, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.J. Work hours and perceived time barriers to healthful eating among young adults. Am. J. Health Behav. 2012, 36, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.H.; Kim, D.H.; Ryu, J.Y. The relationship between working hours and the intention to quit smoking in male office workers: Data from the 7th Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2016–2017). Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 33, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.U.; Lee, W.T.; Kim, M.S.; Lim, M.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Won, J.U. Association between long working hours and physical inactivity in middle-aged and older adults: A Korean longitudinal study (2006–2020). J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2023, 77, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Lee, S.; Jeon, M.J.; Min, Y.S. Relationship between long work hours and self-reported sleep disorders of non-shift daytime wage workers in South Korea: Data from the 5th Korean Working Conditions Survey. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 32, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachito, D.V.; Pega, F.; Bakusic, J.; Boonen, E.; Clays, E.; Descatha, A.; Delvaux, E.; De Bacquer, D.; Koskenvuo, K.; Kroger, H.; et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on alcohol consumption, risky drinking and alcohol use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, E.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugulies, R. Working hours and cardiovascular disease. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2024, 50, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanis, E.; Ozdamar, O. Accommodating Employees with Impairments and Health Problems: The Role of Flexible Employment Schemes in Europe. Merits 2023, 3, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.; Thiese, M.S.; Allen, J.A. Assessing the Relationship between Physical Activity and Depression in Lawyers and Law Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Merits 2024, 4, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Set | Search | Search Details | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working hour | #1 | “Work Schedule Tolerance” [Mesh] OR workhour*[tiab] OR “working hour*”[tiab] OR “overtime*”[tiab] OR work time*[tiab] OR “overwork*”[tiab] OR “extended hour*”[tiab] OR “extended work*”[tiab] OR “work hour*”[tiab] OR “worktime*”[tiab] OR “long hour*”[tiab] OR working hour* [tiab] OR workhour* [tiab] OR “hours of work*”[tiab] OR “hours worked”[tiab] | 28,391 |

| Physical activity/exercise | #2 | “Exercise”[Mesh] OR (physical[tiab] AND activit*[tiab]) OR (physical[tiab] AND inactivit*[tiab]) OR “exercise*”[tiab] OR fitness[tiab] OR sport*[tiab] OR aerobic*[tiab] OR “physical exercise”[tiab] OR workout*[tiab] | 918,344 |

| Nutrition/diet | #3 | “Diet, Food, and Nutrition” [Mesh] OR “diet, healthy”[Mesh Terms] OR “Diet”[MeSH Terms] OR diet*[tiab] OR nutrition*[tiab] OR food[tiab] OR food intake[tiab] OR (food[tiab] AND consumption*[tiab]) OR eat[tiab] OR appetite[tiab] OR feeding*[tiab] OR “Mediterranean diet”[tiab] OR (eating*[tiab] AND habit*[tiab]) OR (diet*[tiab] AND pattern*[tiab]) OR meal*[tiab] OR intake*[tiab] | 2,413,386 |

| Tobacco use | #4 | “Smokers”[Mesh] OR “Smoking”[Mesh] OR “Tobacco Use”[Mesh] OR “Tobacco Use Disorder”[Mesh] OR smoke[tiab] OR smoker*[tiab] OR smoking*[tiab] OR tobacco[tiab] OR cigarette*[tiab] OR sigarette*[tiab] OR nicotine*[tiab] | 474,260 |

| Sleep | #5 | Sleep*[tiab] OR insomnia*[tiab] OR asleep*[tiab] OR awakening[tiab] OR circadian[tiab] | 326,499 |

| Alcohol | #6 | “Alcohol Drinking”[Mesh] OR “alcohol*”[tiab] OR “wine”[tiab] OR “beer”[tiab] OR “liquor”[tiab] OR “spirit”[tiab] OR “alcoholism*”[tiab] OR “substance*”[tiab] OR “drink*”[tiab] OR (heavy[tiab] AND drink*[tiab]) OR (alcohol[tiab] AND depend*[tiab]) OR (alcohol [tiab] AND consumption*[tiab]) OR “alcoholic*”[tiab] OR (alcohol[tiab] AND abuse*[tiab]) OR (drink*[tiab] AND behavior*[tiab]) OR (alcohol[tiab] AND misuse*[tiab]) | 938,466 |

| Other keywords | #7 | “Health Behavior”[Mesh] OR “Health Risk Behaviors”[Mesh] OR “Lifestyle”[tiab] OR “health-related behavior*”[tiab] OR (life[tiab] AND style*[tiab]) OR (health[tiab] AND behavior*[tiab]) | 695,773 |

| Concept: lifestyles | #8 | #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 | 4,913,370 |

| Final | #10 | #1 AND #8 | 9065 |

| Main Category | Subcategory | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Authors | Name of the authors | |

| 2. Title | - | |

| 3. Journal | Published journal | |

| 4. Publication year | - | |

| 5. Origin (country) | The region where the study was conducted | |

| 6. Study design | Type Design | (i) Type of study (e.g., original research, review) (ii) Study design (e.g., qualitative study, cross-sectional, cohort) |

| 7. Population | Sample Size Characteristics | (i) Number of participants, mean follow-up period (ii) Characteristics of the sample (e.g., gender, age, occupation, industrial sector) |

| 8. Working hours | Categorization Measurement | (i) Categorization of working hours (ii) Measurement of working hours (e.g., self-reported, objectively measured) |

| 9. Lifestyle behaviors | Component Measurement | (i) Component of lifestyle behaviors (ii) Measurement of lifestyle behaviors |

| 10. Key findings | Narrative descriptions of the summary of the main findings |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, S.-U.; Won, J.-U.; Yoon, J.-H. Long Working Hours and Unhealthy Lifestyles of Workers: A Protocol for a Scoping Review. Merits 2024, 4, 431-439. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits4040030

Baek S-U, Won J-U, Yoon J-H. Long Working Hours and Unhealthy Lifestyles of Workers: A Protocol for a Scoping Review. Merits. 2024; 4(4):431-439. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits4040030

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Seong-Uk, Jong-Uk Won, and Jin-Ha Yoon. 2024. "Long Working Hours and Unhealthy Lifestyles of Workers: A Protocol for a Scoping Review" Merits 4, no. 4: 431-439. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits4040030

APA StyleBaek, S.-U., Won, J.-U., & Yoon, J.-H. (2024). Long Working Hours and Unhealthy Lifestyles of Workers: A Protocol for a Scoping Review. Merits, 4(4), 431-439. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits4040030