Raising Voice at School: Preliminary Effectiveness and Community Experience of Culture and Practice at an Australian Trauma-Responsive Specialist School

Abstract

:1. Introduction

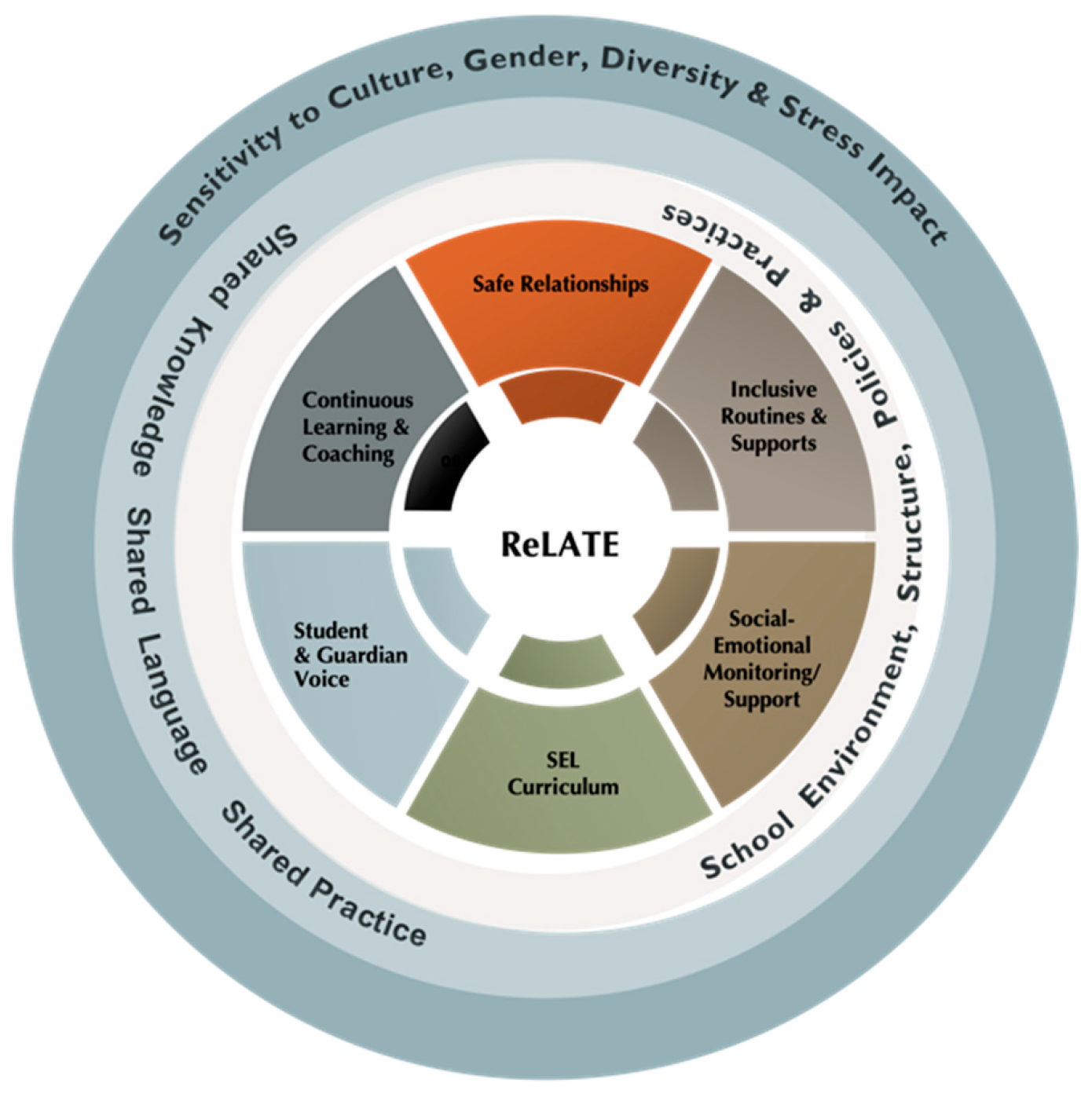

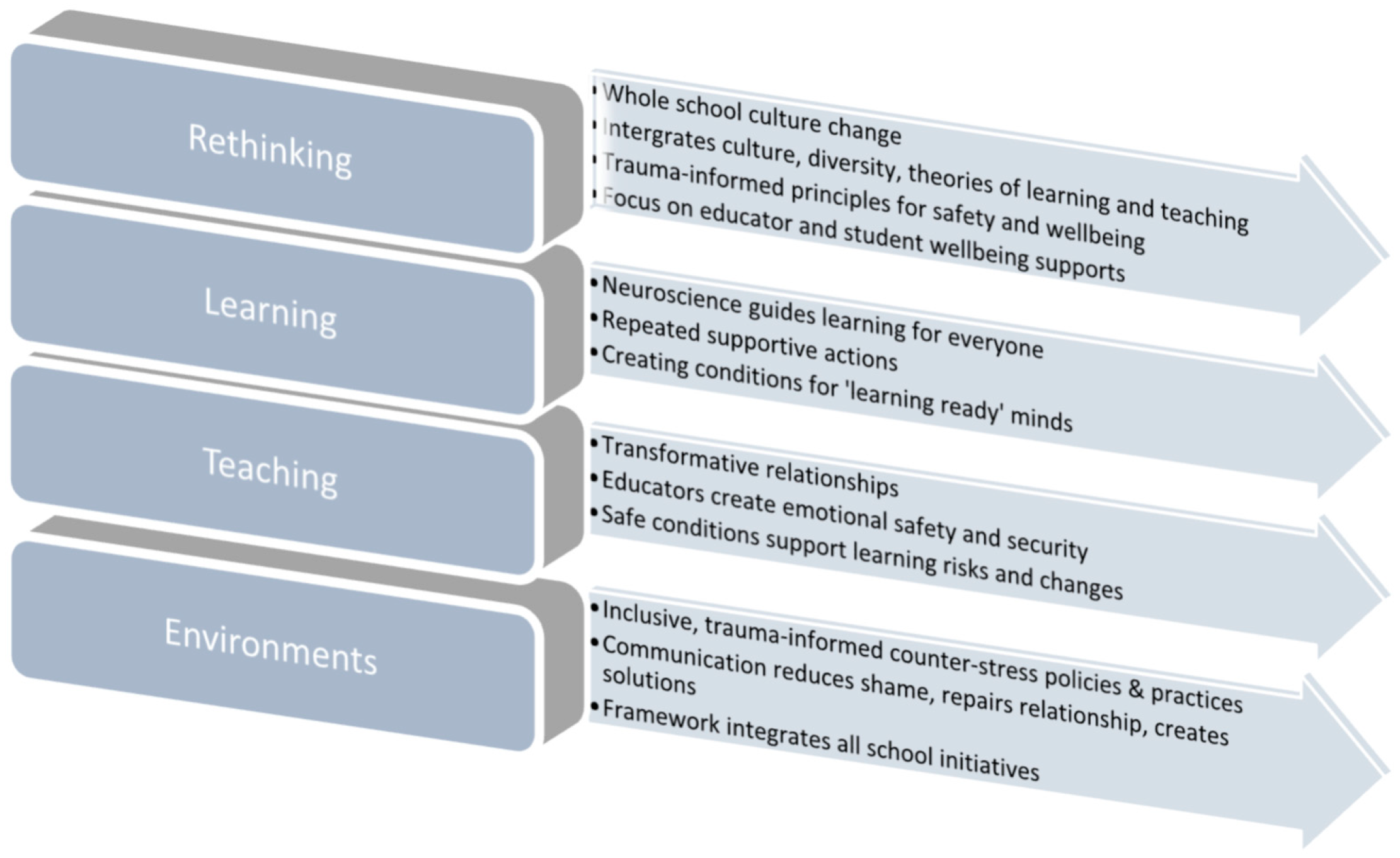

1.1. The Reframing Learning and Teaching Environments (ReLATE) Model

1.2. Purpose of the Study

- What is the evidence of improved student attendance, wellbeing outcomes, and academic progress?

- How is the school experienced by the school community, i.e., students, guardians, educators, and agencies?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Ethics, and Informed Consent

2.2. Setting

2.3. Researchers, Participants, and Recruitment

2.3.1. Researchers

2.3.2. Participants and Recruitment

- Educators. A general outline of the study was emailed to the staff by the principal, with a follow-up invitation to participate in the study offered by the researchers at an all-of-staff meeting. The voluntary nature of the study was highlighted, and the explanatory statement and consent forms were distributed with an expression-of-interest form, interview, and focus group schedules.

- Guardians. Guardians were first notified, via the school newsletter, that researchers would be in the school and that there would be an opportunity to participate in the study to inform ongoing school practice development. The study was further introduced to guardians by staff from the school wellbeing team (reading from a script provided by the researchers) at the conclusion of each student’s regular learning support group meeting held at the beginning of the second school term; an expression-of-interest form was available so that contact details could be provided to the researchers.

- Students. Students were all enrolled at the school in grades F-12 (ages 6–18 years). Students were introduced to the study, alongside their guardians as outlined above. Students whose parents had consented to them participating were required to give their individual assent to participate. There were no exclusionary criteria.

- Agencies. A list of agencies, such as disability services and child and adolescent mental health services, that are regularly involved with students, the referring mainstream (public) schools, and the Catholic Education Office school governing body was provided by the wellbeing team co-ordinator. Initial contact was made via email, outlining the purpose of the study, the research team, and contact details for queries and options to register interest.

2.4. Materials and Procedures

Quantitative Data Gathering

- Attitudes Towards Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale

- 2.

- Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ—Parent Form)

- 3.

- Documentation: Reviews of Policies, Procedures, and Practice Manuals

- 4.

- Employee Engagement Survey (EES)

- 5.

- Department of Education and Training (DET) Review 2019

- 6.

- Catholic Education Melbourne School Improvement Survey (CEMSIS)

2.5. Qualitative Data Gathering

Analysis

2.6. Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics and Characteristics

3.2. Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

- Student Outcomes

- Educator Outcomes

- School Outcomes

- Sub-Themes:

- 1.

- Collective care and understanding. A collective understanding of school practices and a use of shared language was evident in interviews and focus groups. Students across all grade levels explained their personal regulation strategies and described what worked well for them, also describing strategies used by their peers: “I have friends here and we look-out for each other, we know each-others safety-plan and can help suggest stuff” (S2). Guardians spoke of educators at the school as being “teachers that just get-it, whatever they train them in here, they just get it” (G1). Several guardians differentiated between knowledge and understanding, stating, “there’s a difference between teachers’ being taught something and them understanding it”, and “it’s not just one teacher in this school… the whole school understands [my child]” (G5). Participants referred to the attitude of unconditional positive regard and expectations of success educators held and the positive impact that had on students, as summed by this guardian: “compared to other schools [this school] is like apples and oranges to be honest” (G3).

- 2.

- Feelings matter (wellbeing and social–emotional capacity). Educators distinguished their focus on wellbeing as follows: “It’s not that academics’ is not a priority, it’s that your heart would be to make sure the kid is actually coping first, to step back to ‘can we get you in school, engaged and safe?” (E5). They described paying attention to student and staff personal and collective wellbeing: “We’re aware of transference of anxiety from kids to teachers and that there can be a contagion effect with incidents” (E2); “Sticking to the de-brief process I think it’s really important to be able to heal and recover… and… wellbeing meetings… to talk about what teachers are dealing with, what they’re finding difficult” (E2). Students spoke with clarity and satisfaction of their improved emotional capacity and ability to name and recognise feelings and use strategies to regulate them when needed. Students commonly referenced the “zones of regulation” and regulation strategies as reasons why they felt good at school, as stated by this secondary student: “I’ve learnt how to deal with [stress], like ways we can prevent it from happening when we’re sort of getting in the ‘zone’”(S11); similarly, a primary student stated, “we learn how to tell the teachers, and actually talk about [strong emotions] instead of keeping it in, and it’s really calmer and I feel less stress because I have less presure on me” (S1). Improvement in emotional regulation at home was commonly reported by guardians: “Even at home, he’s different with his emotions. Like, I’ll have to growl… but the behaviour will stop. It won’t continue for hours and hours and hours, like it used to. His growth, emotionally, has been really good” (G6).

- 3.

- Trust (consistency, communication, and transparency). Consistency and trustworthiness were viewed as central features of the school, providing routines, predictability, consistent interactions, and follow-through, as expressed by guardian G3: “The students learn to trust them, and I think the teachers deliver on what they’ve said that they’re going to deliver on, so that provides the student the ability to trust by seeing the teachers can be believed”. Educators described the “Big 4” of predictability, consistency, routine, and structure as essential practices for building trust, limiting triggers, and creating environments where social–emotional capacity can be developed within individual student windows of tolerance.

- 4.

- Tell me what I do well, and plan with me to do better (strengths-based, proactive, and preventative). Participants emphasised the positive tone of the school and the proactive building of capacity across emotional, social, learning, and physical capacity, as expressed by a primary student: “They’re more open and instead of giving mean opinions, they give out good opinions. And they teach us how to control our emotions, how to be more kind and more open” (S6); guardians stated, “They all have a lot of nice things to say even though my child is not so nice at times. They tell you the positives, and the negatives are put like ‘here’s what we need to work with you on” (G8), and “it’s alright to get it wrong, then we know what you need help with’, is the message here” (G2). All community agencies emphasised how teachers displayed flexible responses, tailoring curriculum demands to the student’s cognitive availability on any given day: “It is also nice to see teachers meeting students where they are at on that day/in that phase of their life” (A2).

- 5.

- “I am hopeful for the future” (diversity, inclusivity, equity, and access). A secondary student summed the inclusivity of the school with “We all have our differences and it’s ok” (S2). A felt sense of being respected was commonly reported, as expressed by guardian G6: “They include [child’s] culture a lot, he feels very happy with that”. Being able to access the curriculum was also viewed as a distinguishing feature of the school: “They make little steps, like, break it down. Then I can do it and I get to do stuff I enjoy, and I’m interested in” (S2). Guardians considered that relationships at school contributed to improved attendance and learning: “It’s made a massive change to my child, they’re happier to come to school rather than hating school” (G6); “My son, he’s grown heaps emotionally, physically. His stability’s really, really, good. Even at home, he’s different with his emotions” (G10); and “I think even with the time taken on behaviour my child has learnt more here than at the past school” (G8). This theme was reiterated by the participants from community agencies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationality: Centring Connectivity and Optimal Belonging

4.2. Implications for Practice

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emerging Minds. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES): Summary of Evidence and Impact. National Workforce Centre for Child Mental Health. 2020. Available online: https://emergingminds.com.au/resources/background-to-aces-and-impacts/ (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Child Protection Australia. Report and Data Summary 2019–2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2020-21/contents/about (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Redmond, G.; Main, G.; O’donnell, A.W.; Skattebol, J.; Woodman, R.; Mooney, A.; Wang, J.; Turkmani, S.; Thomson, C.; Brooks, F. Who excludes? Young people’s experience of social exclusion. J. Soc. Policy 2022, 53, 236–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIWH. Australian Institute of Health & Welfare: Child Protection Australia 2021–2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2021-22/contents/summary (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Davis, W.; Petrovic, L.; Whalen, K.; Danna, L.; Zeigler, K.; Brewton, A.; Joseph, M.; Baker, C.N.; Overstreet, S.; The New Orleans Trauma-Informed Learning Collaborative. Centering trauma-informed approaches in schools within a social justice framework. Psych. Sch. 2022, 59, 2453–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network; NCTSN Schools Committee. Creating, Supporting, and Sustaining Trauma-Informed Schools: A System Framework; National Center for Child Traumatic Stress: Los Angeles, CA, USA; Durham, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi, S.A.; Flinn, R.E.; Jaure, V.B. Trauma-sensitive schools and social justice: A critical analysis. Urban Rev. 2020, 52, 482–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, A.N. Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. 2017. Available online: https://www.childabuseroyalcommissionresponse.gov.au (accessed on 29 January 2019).

- Bloom, S.L. Trauma theory. In Humanising Mental Health Care in Australia: A Guide to Trauma-Informed Approaches; Richard, B., Haliburn, J., King, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.J. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, 2nd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind & Body in the Transformation of Trauma; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/about.html (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Thomas, S.M.; Crosby, S.; Vanderharr, J. Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: An interdisciplinary review of research. Rev. Res. Educ. 2019, 43, 422–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.F. How Can Educators Create Safe and Supportive School Cultures? Massachusetts Advocates for Children: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Australian Curriculum; Australian Institute of Family Studies. Effects of Trauma on the Brain Development of Children. 2019. Available online: https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Berger, E.; Bearsley, A.; Lever, M. Qualitative evaluation of teacher trauma knowledge and response in schools. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2021, 30, 1041–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach; HHS Publication No. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SMA): Rockville, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 14–4884.

- Cole, S.F. Understanding trauma’s impact on learning: A pathway to creating a school culture where every child living through adversity can grow alongside peers. Sch. Adm. 2019, 2, 30. Available online: https://my.aasa.org/AASA/Resources/SAMag/2019/Feb19/Cole.aspx (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Baker, C.N.; Brown, S.M.; Overstreet, S.; Wilcox, P.D.; New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative. Validation of the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care Scale (ARTIC). Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2021, 13, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, S.L. Organizational stress as a barrier to trauma-informed service delivery. In A Public Health Perspective of Women’s Mental Health; Becker, M., Levin, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, W.; Berg, J.; Osher, D. Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative (TLPI): Trauma-Sensitive Schools Descriptive Study: Final Report; American Institutes for Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, D.H.; Tucker, P.D. Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement: A unified framework. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 513–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.F.; Eisner, A.; Gregory, M.; Ristuccia, J. Helping Traumatized Children Learn: Creating and Advocating for Trauma-Sensitive Schools; Massachusetts Advocates for Children: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval Gomez, A.; McKee, A. When special education and disability studies intertwine: Addressing educational inequities through processes and programming. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 587045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaki, N.; Hopson, L.M.; Middleton, J.S. Sanctuary model implementation from the perspective of indirect care staff. Fam. Soc. 2014, 95, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.C.; Morris, H.; Galvin, E.; Misso, M.; Savaglio, M.; Skouteris, H. Systematic Review of School-Wide Trauma-Informed Approaches. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2020, 14, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, M.; Holden, J. TCI-S Instructors of the Residential Child Care Project. In Therapeutic Crisis Intervention: Reference Guide, 1st ed.; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. Flourish; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, L. A review of school-based positive psychology interventions. Aust. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 28, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.A.; Donoghue, G.M. Learning strategies: A synthesis and conceptual model. npj Sci. Learn. 2016, 11, 16013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network Complex Trauma Task Force, NCTSN. 2003. Available online: https://www.nctsn.org/resources/complex-trauma-children-and-adolescents (accessed on 7 October 2019).

- Bloom, S.L. Encountering trauma, countertrauma, and countering trauma. In Trauma and Countertrauma, Resilience and Counterresilience; Gartner, R.B., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, S.D. An ecological perspective on emerging trauma-informed teaching practices. Child. Sch. 2015, 37, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.C.; Morris, H.; Jones, A.; Skouteris, H.; Deppeler, J. Australian educators’ perceptions and attitudes towards a trauma-responsive school-wide approach. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2021, 15, 71–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.; Deppeler, J.; Skouteris, H.; Crain de Galarce, P.; Morris, H. Changing Educational Paradigms: Trauma-Responsive Relational Practice, Learnings from the USA for Australian Schools. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 138, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, D.G.; Koslouski, J.B.; Perkins, K.N.; Marsico, C.; Porche, M.V. An Evaluation of Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative’s (TLPI) Inquiry-Based Process: Year Three; Boston University, Wheelock College of Education and Human Development: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The MacKillop Institute & MacKillop Family Services. Available online: https://www.mackillopinstitute.org.au/ (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.; Fallot, R.D. Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: A vital paradigm shift. New Dir. Ment. Health Serv. 2001, 89, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, D.J.; Dadds, M.R. Australian data and psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2004, 38, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D. Furthering the use of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: Reliability with younger child respondents. Psych. Assess. 2004, 16, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, L.L.; Janssens, J.M.; Vermulst, A.A.; Van Der Maten, M.; Engels, R.C.; Otten, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher version in children aged 4–7. BMC Psychol. 2015, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diggins, J. Reductions in behavioural and emotional difficulties from a specialist trauma-informed school. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 38, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, E.; Martin, K. School trauma-informed practice policy. Building better schools with evidence-based policy: Adaptable policy for teachers and school leaders. In Building Better Schools with Evidence-Based Policy, 1st ed.; Allen, K.-A., Reupert, A., Oades, L., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champine, R.B.; Lang, J.M.; Mamidipaka, A. Equity-focused, trauma-informed policy can mitigate COVID-19’s risks to children’s behavioural health. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2021, 8, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temkin, D.; Harper, K.; Stratford, B.; Sacks, V.; Rodriguez, Y.; Bartlett, J.D. Moving policy toward a whole school, whole community, whole child approach to support children who have experienced trauma. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisconsin Department of Instruction [WDI Review Tool]. Wisconsin Review Tool for School Policies, Protocols, Procedures & Documents: Examination Using a Trauma-Sensitive School Lens. Available online: https://dpi.wi.gov/sites/default/files/imce/sspw/pdf/tsfidelitytool.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- Best Practice Australia Ltd. (BPA). Analytics. 2020. Available online: https://bpanz.com/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Department of Education and Training (DET). Progress Report, Independent Review. 2020. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Catholic Education Melbourne School Improvement Survey (CEMSIS). In Annual Report to the School Community; MacKillop Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://www.mackillopinstitute.org.au/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Ferguson, R.J.; Robinson, A.B.; Splaine, M. Use of the reliable change index to evaluate clinical significance in SF-36 outcomes. Qual. Life Res. 2002, 11, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, G.L. Reliable Change Index. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology; Kreutzer, J., DeLuca, J., Caplan, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. 2020. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K.A.; Kern, M.L.; Rozek, C.S.; McInereney, D.; Slavich, G.M. Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Aust. J. Psychol. 2021, 73, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpershoek, H.; Canrinus, E.T.; Fokkens-Bruinsma, M.; de Boer, H. The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Res. Pap. Educ. 2020, 35, 641–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiro, B.; Ward, A. Marginalized youth, mental health, and connection with others: A review of the literature. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2020, 37, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brené Brown (Host). Building Brave Spaces [Audio Podcast Episode]. Dare to Lead. 2022. Houston, Texas. Available online: https://brenebrown.com/podcast-show/dare-to-lead/ (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Brown, B. Atlas of the Heart; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dix, K.; Ahmed, S.K.; Carslake, T.; Sniedze-Gregory, S.; O’Grady, E.; Trevitt, J. Student health and wellbeing: A systematic review of intervention research examining effective student wellbeing in schools and their academic outcomes. Main report and executive summary. The Australian Council for Educational Research & Evidence for Learning. Adelaide, South Australia. 2020, pp. 1–67. Available online: https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/assets/Uploads/Main-Report-Student-Health-and-Wellbeing-Systematic-Review-FINAL-25-Sep-2020.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Jackson, C.K.; Porter, S.C.; Easton, J.Q.; Blanchard, A.; Kiguel, S. School Effects on Socioemotional Development, School-Based Arrests, and Educational Attainment. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 2020, 2, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicago Public Schools (CPS). Equity Framework: Creating and Sustaining Equity at the Individual, School, and District Level; Chicago Public Schools Office of Equity: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. The caring relation in teaching. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2012, 38, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A.S.; Darragh, J.J. Critical literacies on the university campus: Engaging pre-service teachers with social action projects. Engl. Teach. Pract. Crit. 2019, 19, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, A.M.; Galloway, M.K. Beyond individual effectiveness: Conceptualizing organizational leadership for equity. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2014, 13, 93–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J. Aboriginal Australia—Trauma stories can become healing stories if we work with therapeutic intent. In Humanising Mental Health Care in Australia: A Guide to Trauma-Informed Approaches; Richard, B., Haliburn, J., King, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, R. Teaching to the North-East: Relationship-Based Learning in Practice Kindle Edition; NZCER Press: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Teaching-North-East-Russell-Bishop-ebook/dp/B07S49YXHM (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Eley, E.; Berryman, M. Paradigm Lost: The loss of bicultural and relation-centred paradigms in New Zealand education and ongoing discrepancies in students’ experiences and outcomes. N. Z. Annu. Rev. Educ. 2020, 25, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures Used to Answer Research Questions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | Focus Groups | ARTIC-ED45 | 1 SDQ | 2 EES | 3 DET | 4 CEMSIS | Wisconsin DI 5 Review Tool | |

| Research Question | Participants: Students (S), Guardians (G), Educators (E), Agencies (A); School Documentation (D) | |||||||

| Q. 1 What is the evidence of improved student wellbeing outcomes and academic progress? | S; G; E; A | S; G; E | G | S; G; E | S; G; E | D | ||

| Q. 2 How is the school experienced by stakeholders, i.e., students, guardians, educators, and agencies? | S; G; E; A | S; G; E | E | E | S; G; E | S; G; E | D | |

| ARTIC-45 ED Subscale | Measure of School Personnel Attitudes |

|---|---|

| Are student behaviours and symptoms viewed as adaptive and malleable or intentional and fixed? |

| Should responses to problem behaviour focus on relationship, flexibility, kindness, and safety as the agents of change or focus on accountability and consequences? |

| Should staff be empathy-focused versus control-focused? |

| Do staff feel able and confident to meet the demands of working with traumatized students, or do they feel unable to meet the demands? |

| Do staff appreciate the effects of secondary trauma and cope by seeking support, or do they minimize the effects of secondary trauma and cope by ignoring or hiding the impact? |

| Do staff feel supportive of and confident about implementation of TIC versus concerned about implementation of TIC? |

| Does the wider system (e.g., administration, supervisors, colleagues) support TIC, or does it not support TIC? |

| Total mean score | Reflecting answers to all items of the ARTIC scale, this is a global score of attitudes toward TIC. |

| ReLATE Study Participant Demographics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Categories | Educator | Educator | Guardian | Guardian | Agency | Agency | Student | Student |

| N = 26 | % | N = 26 | % | N = 6 | % | N = 22 | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 62.5 | 24 | 82.6 | 4 | 66.67 | 5 | 23 | |

| Male | 37.5 | 2 | 17.4 | 1 | 16.67 | 17 | 77 | ||

| LGBTIQ+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16.67 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not specified | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ethnicity | Australian Caucasian | 22 | 84.62 | 4 | 66.67 | 16 | 72.73 | ||

| Australian Aboriginal or TSI | 0 | 0 | 2 | 17.4 | 1 | 16.67 | 3 | 13.64 | |

| European (German, Serbian, British) | 3 | 11.11 | 1 | 1 | 16.67 | 1 | 4.55 | ||

| New Zealand Caucasian | 1 | 3.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not specified | 2 | 7.41 | 2 | 17.4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9.09 | |

| Age (years) | ≤29 | 5 | 18.52 | 1 | 3.87 | 0 | 0 | Age | |

| 30–39 | 9 | 33.33 | 6 | 23.08 | 2 | 33.33 | 6–9 | 27.27 | |

| 40–49 | 9 | 33.33 | 15 | 57.69 | 3 | 50 | 10–14 | 31.82 | |

| ≥50 | 4 | 14.81 | 4 | 15.38 | 1 | 16.67 | 14–18 | 45.45 | |

| Teacher qualifications All teachers certified with Bachelor of Education minimum qualification | |||||||||

| Teaching experience (years) | ≤4 | 2 | 7.41 | ||||||

| 5 to 9 | 9 | 33.33 | |||||||

| 10 to 14 | 9 | 33.33 | |||||||

| 15+ | 5 | 18.52 | |||||||

| Level of trauma training 1–7 (1 = brief & little follow-up, 7 = very extensive & ongoing support) | <3 | 0 | |||||||

| 3–5 | 37.04 | ||||||||

| 5–7 | 62.96 | ||||||||

| Trauma training/support satisfaction | |||||||||

| 1 (low)–7 (high) | 1 to 3 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| 4 to 5 | 8 | 29.63 | |||||||

| 6 to 7 | 19 | 70.37 | |||||||

| Measure | Item | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| School statistics | Staff retention Staff attendance | 86.5 94.4 |

| Employee Engagement Survey | Level of engagement | (% of engaged staff) |

| Mid-2014 (year 1) Culture of Consolidation | 42 | |

| Mid-2015 (year 2) Culture of Success | 62 | |

| Mid-2019 (year 6) Culture of Success | 88.7 | |

| CEMSIS 1 2019 (April–May) Educator views |

| 85 |

| 75 | |

| 80 | |

| Student views |

| 71 (P 2); 51 (S 3) 72 (P and S) 62 (S) |

| Guardian views Primary age child (P) Secondary age child (S) |

| 85 (P); 82; 82 (S) 81 (P and S) 80 (P); 84 (S) 72 (P and S) |

| DET 4 (July 2019–Jan 2020) | NB: Regular attendance at school = attending 90% of the school year Student attendance at previous school (AVE across student population) Student attendance after 12 months at the school (AVE) Students with Individual Education Plans (IEPs) with 4 key goals Achievement or progress towards planned outcomes/goals 1379 IEPs created; 965 goals successfully achieved Academic goals achieved Attendance goals achieved Transition goals (to mainstream school, tertiary education, or employment training) Engagement goals | % 56 83 100 70 70 65 68 75 72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avery, J.C.; Galvin, E.; Deppeler, J.; Skouteris, H.; Roberts, J.; Morris, H. Raising Voice at School: Preliminary Effectiveness and Community Experience of Culture and Practice at an Australian Trauma-Responsive Specialist School. Trauma Care 2023, 3, 331-351. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3040028

Avery JC, Galvin E, Deppeler J, Skouteris H, Roberts J, Morris H. Raising Voice at School: Preliminary Effectiveness and Community Experience of Culture and Practice at an Australian Trauma-Responsive Specialist School. Trauma Care. 2023; 3(4):331-351. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3040028

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvery, Julie C., Emma Galvin, Joanne Deppeler, Helen Skouteris, Justin Roberts, and Heather Morris. 2023. "Raising Voice at School: Preliminary Effectiveness and Community Experience of Culture and Practice at an Australian Trauma-Responsive Specialist School" Trauma Care 3, no. 4: 331-351. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3040028

APA StyleAvery, J. C., Galvin, E., Deppeler, J., Skouteris, H., Roberts, J., & Morris, H. (2023). Raising Voice at School: Preliminary Effectiveness and Community Experience of Culture and Practice at an Australian Trauma-Responsive Specialist School. Trauma Care, 3(4), 331-351. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3040028