Race-Based Social Rejection and Mental Health: The Role of Racial Identity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Moderators

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pascoe, E.A.; Richman, L.S. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chin, D.; Loeb, T.B.; Zhang, M.; Liu, H.; Cooley-Strickland, M.; Wyatt, G.E. Racial/ethnic discrimination: Dimensions and relation to mental health symptoms in a marginalized urban American population. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegrıa, M.; Canino, G.; Shrout, P.E.; Woo, M.; Duan, N.; Vila, D.; Meng, X.-L. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 359–369. [Google Scholar]

- Belle, D.; Doucet, J. Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among U.S. women. Psychol. Women Q. 2003, 27, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.; Beiser, M.; Kaspar, V.; Hou, F.; Rummens, J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression and coping: A study of southeast Asian refugees in Canada. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999, 40, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.T.; Metzger, I.W.; Leins, C.; Delapp, C. Assessing racial trauma within a DSM-5 framework: The UConn racial/ethnic stress & trauma survey. Pract. Innov. 2018, 3, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Neighbors, H.W.; Jackson, J.S. Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Health: Findings from Community Studies. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 200–208. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, L.; Vallejo, L. Ethnic discrimination and Latino depression: The mediating role of traumatic stress symptoms and alcohol use. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2015, 21, 517–526. [Google Scholar]

- Nadimpalli, S.B.; James, L.; Yu, F.; Cothran, F.; Barnes, L.L. The association between discrimination and depressive symptoms among older African Americans: The role of psychological and social factors. Exp. Res. Aging 2015, 41, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.L.; Ahn, S. Discrimination against Latina/os: A meta-analysis of individual-level resources and outcomes. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 40, 28–65. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sue, D.W.; Capodilupo, C.M.; Holder, A.M. Racial microaggressions in the life experiences of Black Americans. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2008, 39, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M. Complex Racial Trauma: Evidence, Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 18, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Menaghan, E.G.; Lieberman, M.A.; Mullan, J.T. The stress process. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1981, 22, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gone, J.P.; Hartmann, W.E.; Pomerville, A.; Wendt, D.C.; Klem, S.H.; Burrage, R.L. The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: A systematic review. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, D.K.; Kim, J.H.J.; Wu, K. The Japanese American wartime incarceration: Examining the scope of racial trauma. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondolo, E.; Hausmann, L.; Jhalani, J.; Pencille, M.; Atencio-Bacayon, J.; Kumar, A.; Kwok, J.; Ullah, J.; Roth, A.; Chen, D.; et al. Dimensions of Perceived Racism and Self-Reported Health: Examination of Racial/Ethnic Differences and Potential Mediators. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 42, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, N.I.; Lieberman, M.D. Why It Hurts to Be Left Out: The Neurocognitive Overlap Between Physical and Social Pain. In The Social Outcast: Ostracism, Social Exclusion, Rejection, and Bullying, 1st ed.; Williams, K.D., Forgas, J.P., von Hippel, W., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2005; pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J.S. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: A review of research. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmore, R.D.; Deaux, K.; McLaughlin-Volpe, T. An organizing framework for collective identity: Articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 80–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cokley, K. Critical issues in the measurement of ethnic and racial identity: A referendum on the state of the field. J. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 4, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Tummala-Narra, P. Ethnic identity, perceived support, and depressive symptoms among racial minority immigrant-origin adolescents. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2015, 85, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, A.; Tikhonov, A.; Ellman, L.M.; Kern, D.M.; Lui, F.; Anglin, D. Ethnic identity and perceived stress among ethnically diverse immigrants. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Phinney, J.S.; Horenczyk, G.; Liebkind, K.; Vedder, P. Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 493–510. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, R.M.; Shelton, J.N. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 1079. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, B.; Fan, W.; Tran, T.V.; Takeuchi, D.T. The role of racial/ethnic identity in the association between racial discrimination and psychiatric disorders: A buffer or exacerbator? SSM-Popul. Health 2019, 7, 100378. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh, S.A.; Taylor, A.B.; Stuhlsatz, G.L.; Neppl, T.K.; Lohman, B.J. Family and community support among sexual minorities of color: The role of sexual minority identity prominence and outness on psychological well-being. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2019, 16, 1593279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, H.F.; Wyatt, G.E.; Ullman, J.B.; Loeb, T.B.; Chin, D.; Prause, N.; Zhang, M.; Williams, J.K.; Slavich, G.M.; Liu, H. Cumulative burden of lifetime adversities: Trauma and mental health in low-SES African Americans and Latino/as. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2015, 7, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Coles, M.E.L.; Constantine, M.G. Racism-related stress, Africultural coping, and religious problem-solving among African Americans. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2006, 12, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.Y.; Kendall, D.L.; Webb, M. Religious coping moderates the relation between racism and psychological well-being among Christian Asian American college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 62, 87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowen-Reid, T.; Harrell, J. Racist Experiences and Health Outcomes: An Examination of Spirituality as a Buffer. J. Black Psychol. 2002, 28, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternthal, M.J.; Williams, D.R.; Musick, M.A.; Buck, A.C. Religious practices, beliefs, and mental health: Variations across ethnicity. Ethn. Health 2012, 17, 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, T.M.; Cavalhieri, K.E. The role of coping strategies in understanding the effects of institutional racism on mental health outcomes for African American men. J. Black Psychol. 2019, 45, 405–433. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz, L. Racial trauma recovery: A race-informed therapeutic approach to racial wounds. In The Cost of Racism for People of Color: Contextualizing Experiences of Discrimination; Alvarez, A.N., Liang, C.T.H., Neville, H.A., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census Reporter, April, 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/CA/INC110223#INC110223 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Glover, D.A.; Williams, J.K.; Kissler, K.A. Using novel methods to examine stress among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men and women. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 36, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondolo, E.; Kelly, K.P.; Coakley, V.; Gordon, T.; Thompson, S.; Levy ECassells, A.; Tobin, J.N.; Sweeney, M.; Contrada, R.J. The Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire: Development and Preliminary Validation of a Community Version. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 335–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B.; Cashman, L.; Jaycox, L.; Perry, K. The validation of a self-report measure of post-traumatic stress disorder: The post-traumatic diagnostic scale. Psychol. Assess. 1997, 9, 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E.B.; McLean, C.P.; Zang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Powers, M.B.; Kauffman, B.Y.; Rauch, S.; Porter, K.; Knowles, K. Psychometric properties of the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale for DSM–5 (PDS–5). Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1166. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, M.; Gillihan, S.; Rosenfield, D.; Jerud, A.; Foa, E. Reliability and validity of the PDS and PSS-I among participants with PTSD and alcohol dependence. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 617–623. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.T.; Malcoun, E.; Sawyer, B.A.; Davis, D.M.; Bahojb Nouri, L.; Bruce, S.L. Cultural adaptations of prolonged exposure therapy for treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in African Americans. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 102–124. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Prause, N.; Wyatt, G.; Williams, J.; Chin, D.; Davis, T.; Loeb, T.; Marchand, E.; Zhang, M.; Myers, H. Development of a composite trauma exposure risk index. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M.A.; Heilemann, M.V.; Ang, A.; Nevarez, F.; Mangione, C.M. Intimate partner violence, depression and PTSD among pregnant Latina women. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, E. Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in African American and Black Caribbean US adults. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, G.; DeCoster, J.; Huang, C.; Chiriboga, D. Race/ethnicity and the factor structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: A meta-analysis. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2011, 17, 381–396. [Google Scholar]

- Vilagut, G.; Forero, C.; Barbaglia, G.; Alonso, J. Screening for Depression in the General Population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155431. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J.S. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A New Scale for Use with Diverse Groups. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, D.; Buhagiar, A. Psychometric evaluation of the Spiritual Coping Strategies scale in English, Maltese, back-translation and bilingual versions. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 42, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elliott, D.M.; Mok, D.S.; Briere, J. Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. J. Trauma. Stress 2005, 17, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, S.; Stein, J.A.; Siegel, J.M.; Golding, J.M.; Burnam, M.A. The prevalence of adult sexual assault: The Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area Project. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1987, 126, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Kern, M.L.; Rozek, C.S.; McInerney, D.M.; Slavich, G.M. Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Aust. J. Psychol. 2021, 73, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bor, J.; Venkataraman, A.; Williams, D.R.; Tsai, A. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet 2018, 392, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, T.; Gee, G.C.; Takeuchi, D.T. Racial discrimination and psychological distress: The impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheah, C.S.; Wang, C.; Ren, H.; Zong, X.; Cho, H.S.; Xue, X. COVID-19 racism and mental health in Chinese American families. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020021816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Banawa, R.; Oh, H. The mental health impact of COVID-19 racial and ethnic discrimination against Asian American and Pacific Islanders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 708426. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Qian, Y.; Wilkes, R. Anti-Asian discrimination and the Asian-white mental health gap during COVID-19. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2020, 44, 1851739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, A.; Yellow Horse, A.; Jeung, R. Stop AAPI Hate Mental Health Report. 2021. Available online: https://stopaapihate.org/mental-health-report/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Anderson, R.E.; Stevenson, H.C. RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Race, gender, and sexual harassment. S. Calif. Law Rev. 1991, 65, 1467. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 31, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, G.L.; Garcia, J. Identity, belonging, and achievement: A model, interventions, implications. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 17, 365–369. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, G.M.; Cohen, G.L. A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Anglin, D.M.; Dyar, C.; Alvarez, K. Intersectional approaches to risk, resilience, and mental health in marginalized populations: Introduction to the special section. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 2023, 132, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pearlin, L.I. The sociological study of stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1989, 30, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearlin, L.I. The life course and the stress process: Some conceptual comparisons. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 65, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean or N (S.D. or %) | |

|---|---|

| Age | m = 41.7 (10.2) |

| Gender | |

| men | 167 (72.61%) |

| women | 63 (27.39%) |

| Income a | |

| ≤1249/m | 157 (86.26%) |

| >1249/m | 25 (13.74%) |

| Education b | |

| less than high school | 58 (25.33%) |

| high school+ | 171 (74.67%) |

| Spiritual Coping | 55 (11.3) |

| Race-Based Social Rejection | 15.4 (5.9) |

| Racial/ethnic Identity | 12.1 (3.1) |

| PTS Symptoms | 12.3 (11.6) |

| Depression Symptoms | 17.9 (12.5) |

| Age | Gender | Income | Education | Spiritual Coping | Social Rejection | Racial Identity | PTSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.33 | |||||||

| <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Income | −0.1 | 0.03 | ||||||

| 0.1918 | 0.6696 | |||||||

| Education | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.05 | |||||

| 0.1928 | 0.9196 | 0.4664 | ||||||

| Spiritual Coping | 0.09 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.12 | ||||

| 0.1776 | 0.3915 | 0.8131 | 0.082 | |||||

| Social Rejection | −0.1 | −0.17 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.02 | |||

| 0.1294 | 0.0116 | 0.3441 | 0.2882 | 0.7359 | ||||

| Racial Identity | 0.13 | −0.003 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.07 | ||

| 0.059 | 0.9655 | 0.7288 | 0.3623 | <0.0001 | 0.2614 | |||

| PTS Symptoms | −0.18 | −0.26 | −0.1 | −0.13 | −0.07 | 0.44 | −0.09 | |

| 0.0056 | <0.0001 | 0.1683 | 0.0453 | 0.2711 | <0.0001 | 0.1945 | ||

| Depression Symptoms | −0.15 | −0.2 | −0.08 | −0.13 | −0.14 | 0.46 | −0.23 | 0.7 |

| 0.0275 | 0.0029 | 0.2758 | 0.055 | 0.0362 | <0.0001 | 0.0006 | <0.0001 |

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard | t Value | Pr > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error | ||||

| Age | −0.03590332 | 0.07593172 | −0.47 | 0.6368 |

| Gender (Men) | −3.13002031 | 1.72774789 | −1.81 | 0.0714 |

| Education (High School+) | −1.99247371 | 1.64876462 | −1.21 | 0.2282 |

| Spiritual Coping | −0.05192862 | 0.06721352 | −0.77 | 0.4406 |

| Racial Identity | −0.9572892 | 0.24640139 | −3.89 | 0.0001 |

| Social Rejection | 0.96053349 | 0.1231848 | 7.8 | <0.0001 |

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard | t Value | Pr > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error | ||||

| age | −0.05895285 | 0.07090537 | −0.83 | 0.4066 |

| gender (men) | −5.25647312 | 1.62886805 | −3.23 | 0.0014 |

| education (high school+) | −2.30046618 | 1.54147419 | −1.49 | 0.1371 |

| spiritual Coping | −0.03758428 | 0.06158164 | −0.61 | 0.5423 |

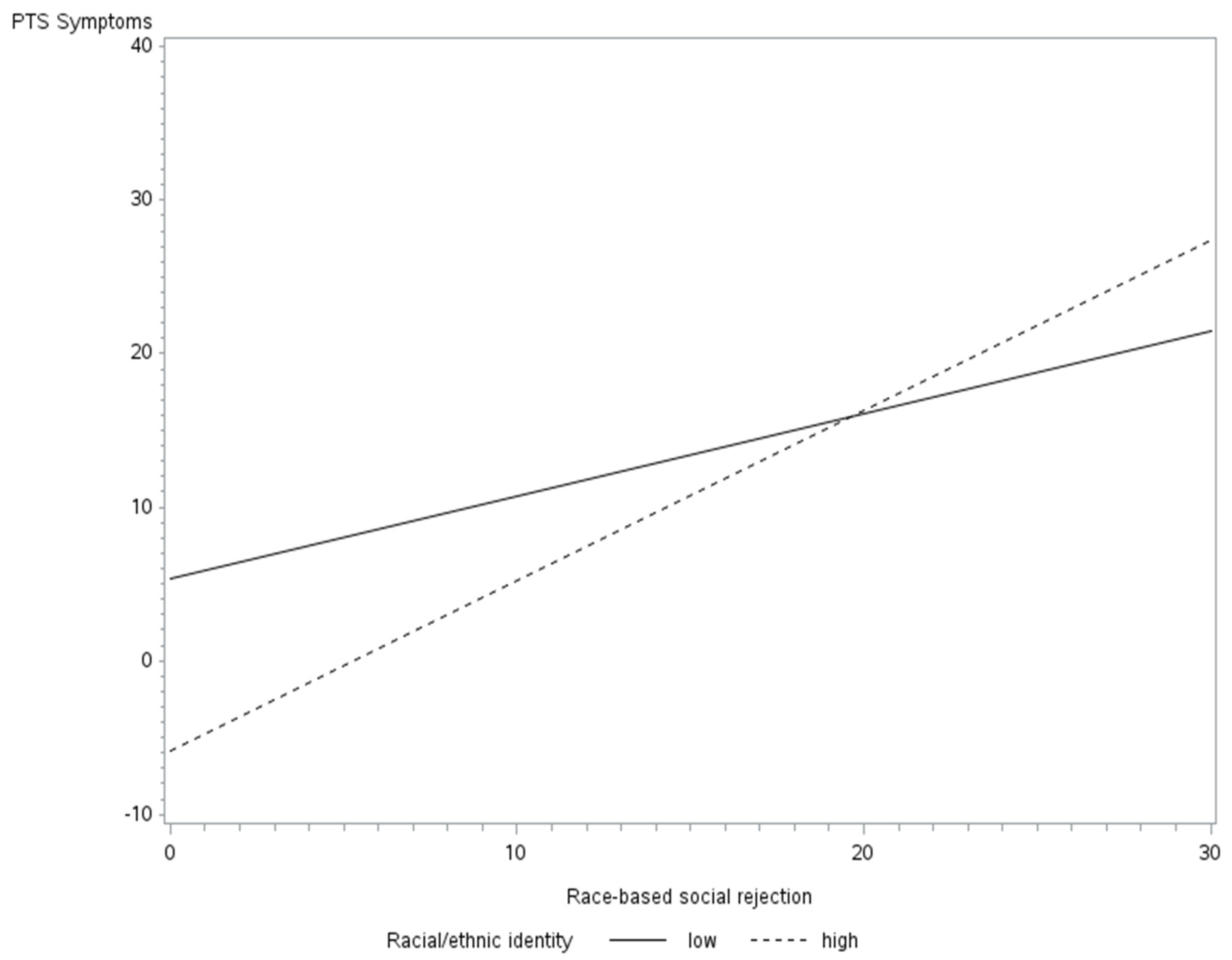

| racial identity (high) | −11.57913905 | 3.78853176 | −3.06 | 0.0025 |

| social rejection | 0.43766055 | 0.18090015 | 2.42 | 0.0164 |

| social rejection * racial identity (high) | 0.59214587 | 0.23154384 | 2.56 | 0.0112 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chin, D.; Loeb, T.B.; Zhang, M.; Cooley-Strickland, M.; Pemberton, J.V.; Wyatt, G.E. Race-Based Social Rejection and Mental Health: The Role of Racial Identity. Trauma Care 2025, 5, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare5020006

Chin D, Loeb TB, Zhang M, Cooley-Strickland M, Pemberton JV, Wyatt GE. Race-Based Social Rejection and Mental Health: The Role of Racial Identity. Trauma Care. 2025; 5(2):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare5020006

Chicago/Turabian StyleChin, Dorothy, Tamra B. Loeb, Muyu Zhang, Michele Cooley-Strickland, Jennifer V. Pemberton, and Gail E. Wyatt. 2025. "Race-Based Social Rejection and Mental Health: The Role of Racial Identity" Trauma Care 5, no. 2: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare5020006

APA StyleChin, D., Loeb, T. B., Zhang, M., Cooley-Strickland, M., Pemberton, J. V., & Wyatt, G. E. (2025). Race-Based Social Rejection and Mental Health: The Role of Racial Identity. Trauma Care, 5(2), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare5020006