Abstract

Biodegradable materials are emerging as a sustainable alternative to conventional petroleum-based plastics across packaging, sanitation, and agriculture sectors. These materials naturally decompose into harmless substances within a specified period, completing an eco-friendly lifecycle. However, the widespread adoption of biodegradable plastics depends on building confidence among consumers, manufacturers, and regulators regarding their effectiveness. This study employed a mixed-methods approach to investigate the key factors influencing biodegradable plastics’ sustainability, integrating theoretical frameworks with survey data collected from Malaysian plastic users aged 15 and above. Results revealed that individual characteristics, particularly environmental self-identity, significantly influence behavioural intentions toward sustainable practices, such as choosing eco-friendly packaging. The findings contribute to the theoretical understanding of biodegradable plastics adoption in developing markets while providing actionable insights for government and corporate stakeholders. This study recommends targeted awareness campaigns emphasising environmental self-identity to reduce conventional packaging use and promote biodegradable alternatives. By incorporating these identity-focused messages into marketing communications, organisations can enhance public awareness and market perception of biodegradable products.

1. Introduction

The ubiquity of plastic materials in modern society spans diverse applications, from textiles and electronics to healthcare items and packaging [1]. Non-biodegradable plastics, characterised by their artificial or semi-artificial organic molecular composition, have revolutionised manufacturing through their exceptional properties—mechanical strength, lightness, flexibility, and durability—while maintaining cost-effectiveness compared to traditional materials like paper, glass, and metals [2]. These characteristics have made non-biodegradable plastics indispensable in contemporary industrial processes and consumer products, fundamentally transforming global manufacturing paradigms.

However, this widespread adoption has created significant environmental challenges. Global petroleum-based plastic production reached 367 million tonnes in 2023 [3], with annual plastic waste generation exceeding 40 million tonnes. Alarmingly, 93% of this waste ends up in oceans and landfills, where its degradation releases substantial amounts of CO2 and hazardous substances—each kilogramme of plastic producing approximately 2.8 kg of CO2 when burned [4]. The accumulation of microplastics in marine ecosystems has reached critical levels, with recent studies detecting these particles in remote Arctic ice cores and deep-sea sediments [5].

In response to these environmental concerns, biodegradable plastics have emerged as a promising sustainable alternative. These materials, derived from natural resources such as cellulose, starch, and other carbohydrates, offer a crucial advantage. This material can be broken down by microorganisms like bacteria, algae, and fungi under specific environmental conditions [6]. Advanced biotechnology techniques have enabled the development of next-generation biodegradable plastics with enhanced mechanical properties and controlled biodegradation rates [7]. The global biodegradable plastics market reflects this potential, with production projected to reach 7.5 million tonnes by 2024 [8], driven by rising fossil fuel prices and increasing environmental regulations.

Despite their environmental benefits, the widespread adoption of biodegradable plastics faces several challenges. These include higher production costs, mechanical limitations [9], and complex sustainability considerations in an increasingly globalised market [10]. Recent life cycle assessments have revealed that the sustainability of biodegradable plastics involves intricate trade-offs between environmental impact, economic viability, and social equity considerations [11].

The transition to biodegradable plastics in developing economies like Malaysia presents unique challenges and opportunities. While several studies have examined global trends in biodegradable plastics adoption [3,12], limited research has investigated the specific determinants of biodegradable plastic sustainability in the Malaysian context [13]. This gap is particularly significant given Malaysia’s position as a key manufacturing hub in Southeast Asia and its recent environmental initiatives, including the National Plastic Sustainability Roadmap 2024–2030 [14].

This study addresses this research gap by investigating the key determinants of biodegradable plastic sustainability in Malaysia’s manufacturing sector. This study develops a comprehensive conceptual framework integrating environmental, economic, and social factors, providing valuable insights for industry stakeholders and policymakers. This research is particularly timely as organisations increasingly incorporate environmental sustainability into their strategic planning while navigating the complex landscape of sustainable manufacturing practices.

2. Recent Advances in Biodegradable Plastic Production

The global plastic crisis has reached unprecedented levels, with an estimated 400 million tons of plastic waste generated annually [15]. This environmental challenge has catalysed intensive research into biodegradable alternatives, particularly over the past three decades [16]. Recent advances in this field have opened new possibilities for sustainable packaging solutions while addressing growing environmental concerns. The development of biodegradable plastics has evolved significantly, with researchers exploring various polyesters, non-biodegradable polymers, and innovative composites. A breakthrough came with the development of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), which are completely biodegradable polyesters produced by microorganisms [17]. These materials have shown promising results in both durability and decomposition rates, making them potential candidates for widespread commercial adoption.

Performance requirements for biodegradable plastics in food-packaging applications remain stringent, necessitating materials that can maintain structural integrity across diverse environmental conditions while ensuring food safety [18]. Recent innovations have focused on enhancing thermal stability, moisture resistance, and mechanical properties through various approaches, including nanotechnology integration and polymer blending [19]. The emergence of novel processing techniques has significantly improved the production efficiency of biodegradable plastics. Advanced bacterial fermentation methods have reduced production costs by up to 40% compared to traditional methods [20]. Additionally, incorporating agricultural waste as feedstock has created a dual benefit: waste reduction and sustainable material production.

Climate change concerns have accelerated the transition toward zero-emission manufacturing processes [21]. This shift has prompted research into carbon-neutral production methods for biodegradable polymers. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of using atmospheric CO2 as a feedstock for polymer synthesis, potentially creating a circular economy approach to plastic production [22]. Emerging technologies in enzyme engineering have revolutionised the biodegradation process. Scientists have identified and modified specific enzymes that can accelerate the decomposition of biodegradable plastics under controlled conditions [23]. This breakthrough addresses one of the major challenges in biodegradable plastic development: ensuring complete decomposition within a reasonable timeframe.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in scaling up production while maintaining cost-effectiveness [24]. Recent market analyses suggest that biodegradable plastics currently represent only 1% of global plastic production, which is expected to grow significantly by 2030 [25]. The industry faces the ongoing challenge of balancing performance requirements with environmental benefits and economic viability. Research increasingly focuses on “smart” biodegradable materials that can respond to environmental triggers, enhancing their functionality while maintaining their eco-friendly characteristics [26]. These innovations, combined with stricter environmental regulations and growing consumer awareness, are expected to accelerate the adoption of biodegradable plastics across various industries.

3. Research Methods and Materials

3.1. Research Philosophical Justifications

Bloomberg and Volpe [27] describe a knowledge claim as a specific argument for what and how the researcher might learn. A research design includes anything from broad assumptions or explanations to particular data collection and analysis methods. As a result, all judgments should be based on knowledge claims or philosophical reasons (world views) that underpin overall decisions at every level of study. The world views of a researcher are the beliefs that guide their research [28]. Morgan [29] defined world perspective as a shared set of beliefs that influences the information sought and how the researcher collects and analyses evidence. As a result, global views are critical in directing the research endeavour of performing a mixed-methods study [30,31]. According to Bloomberg and Volpe [27] and Creswell and Plano Clark [32], world perspectives differ in the research’s ideas’ components. They are ontology (the nature of reality), epistemology (the connection between the researcher and the subject of the study), axiology (the role of value), rhetoric (the language of research), and study procedures (methodology). The worldviews that drive the entire research process are explained in the following sections.

In order to fulfil this study’s research aims, social constructionism and post-positivism methodologies were used in this study’s design. This methodology is called “sequential exploratory mixed methods research” because it allows the methods to complement and produce more thorough results. Social constructionism is an ontological position that asserts that social actors continually accomplish social phenomena and their meanings [32]. Social constructivism is the ontology adopted in the first phase of research. Post-positivism argues that the discovery is only a reasonable measure of the truth; reality will never be fully grasped. Post-positivism is a term that accurately describes today’s quantitative researchers [33]. In this work, the post-positivist ontology guides all decisions taken throughout the quantitative phase. Therefore, this paper aims to detail the many research approaches used to examine the factors that influence the sustainability of biodegradable materials. A mixed-methods study method is used to investigate these factors and foresee how they may affect the sustainability of biodegradable plastics.

3.2. Research Strategy

This study, conducted from February 2022 to January 2023, discusses sequential exploratory mixed methods concerning the research methods used to investigate the determinants for the sustainability of biodegradable plastics. This study aims to improve biodegradable plastics’ effectiveness by creating a conceptual underpinning for their long-term sustainability. In order to achieve the research objectives, the analysis was performed in two stages, as illustrated in Table 1. In the first phase, the researcher decided to learn more thoroughly, explain more, and qualitatively pinpoint the quantitative survey results. Consequently, the first four research questions typically drive the qualitative process. In the qualitative study (phase one), multiple cases were chosen to enhance transferability to other contexts, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), government agencies (national solid waste management department), and biodegradable plastic producers were the participants. In the second stage (quantitative research), the researcher aims to analysed statistical relationships between the variables [34]. Therefore, in this study, researching factors influencing the sustainability of biodegradable plastics is followed by an inductive approach of reasoning to understand the phenomena and come to a point to integrate the relationship of factors with the sustainability of biodegradable plastics. Therefore, based on the phase one result, the finding of the qualitative phase was used as the input for the development of the quantitative phase of this study. So, despite the prevalence of many theories in the domain, it was decided to understand what is happening in reality and how new knowledge can be created [35]. Therefore, a deduction approach is followed; the developed hypotheses are based on theory and examine the variables’ relationship. The sequential explanatory design has drawbacks, such as difficulties initially obtaining ethics approval for the entire project (as researchers may not know how the participant selection for the second phase will be conducted until the first phase has been completed).

Table 1.

Research methodology, research strategy, and research design.

4. Research Method 1—In-Depth Interviews

The guidance for an interview is referred to as the interview protocol. It specifies what should be stated at the start of the interview to identify oneself and the subject of the conversation. The study’s methodology began with interviews conducted at companies that manufacture biodegradable plastic and government agencies and non-governmental organisations in Malaysia. These interviews aimed to summarise these entities’ roles in understanding the determinants for the sustainability of biodegradable plastic. The conclusions of this qualitative study were based on interviews with seven persons from seven distinct organisations in Malaysia. The research population comprised three different types of Malaysian organisations: two government agencies, two non-governmental organisations, and three firms that manufacture biodegradable plastic. The interviews were conducted online using Google Meetings. The interviews were of varying lengths and were conducted at times convenient for the interviewers and the people being interviewed.

The organisations were selected based on their demonstrated commitment to environmental issues, which was demonstrated either by the awarding of environmental honours to them or the existence of ecologically significant patents on their premises. Organizations, such as those that produce biodegradable plastic, government agencies, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), served as the unit of analysis for this study to obtain a deeper comprehension of the phenomenon. Each interview took an hour and a half to complete, and we were able to consider all of the questions asked carefully. After that, we transcribed the interviews and looked at the data using within- and between-case analyses. Correct translation procedures were employed to ensure that the comments were coherent. This was carried out to make sure that the comments were true. The researcher entered the interview data and the qualitative data provided by the participants into the ATLAS.ti 9 programme and transcribed the interviews.

This section follows the framework of the segment on the methodology, and it discusses in full every facet of the testing technique. The information acquired during this enquiry may be saved, interpreted, and assessed with the help of the ATLAS.ti 9 software. Those unfamiliar with the ATLAS.ti 9 ecosystem will likely be confused by the use of terms like “quotation”, “relations”, and “network”, all of which are technical terms. Following an initial textual analysis, the researcher might employ the open coding feature of the ATLAS.ti 9 programme. Using this feature, the researcher may find several vital words and phrases that pertain to the article’s or topic’s subject matter.

Participant Demographics

Seven participants from seven different Malaysian organisations were interviewed for this qualitative research. Three biodegradable plastic companies, since there are limited biodegradable plastic companies currently in Malaysia, two government agencies, and two NGOs from diverse Malaysian organisations made up the study’s population. The snowball technique for purposeful sampling was utilised, and it was with its help that the questioned informants were selected. The number of interviews was kept to a minimum to prevent information overload. Following the first round of questions, the interview was concluded since there was no new information to be gathered from additional sources of information after the initial round of questions. For instance, on 24 March 2023, from eleven in the morning to twelve-thirty in the afternoon, an interview with the first participant, a manager at one of the biodegradable plastic firms in Malaysia, took place. On 2 April 2023, from noon to 1:30 p.m., an interview with the second participant (a non-governmental organisation) took place. Pseudonyms have been used instead of the informants’ real names to protect their identities and preserve their secrecy. Table 2 provides more information on the participants.

Table 2.

Profile of informants.

Table 2 reveals that all informants had senior positions and worked for the company for over five years. They were all senior members of staff. Master’s and bachelor’s degrees were also awarded to them. Because of this, each informant is highly knowledgeable and skilled about environmental issues and biodegradable plastics production. They are also recognised for their expertise in disseminating knowledge about the factors determining biodegradable plastic’s sustainability.

5. To Explore the Factors Influencing the Sustainability of Biodegradable Plastics

According to the findings from phase one, individual factors were identified as the most important predictors of the sustainability of biodegradable plastics in Malaysia. The dimensions of individual factors considered for this study are environmental value, environmental knowledge, environmental attitude, perceived benefits, perceived risk, social norm, personal norm, regulatory pressure, responsibility ascription, and sustainability behavioural intention. The interviews made it evident that the participants preferred to discuss the elements that affect the long-term survival of biodegradable polymers since they thought doing so was easier. Regarding the technology’s cost, the participants also addressed their expectations for biodegradable polymers in ecologically friendly packaging. Most participants based their estimation of ecologically suitable packaging on their individual assessments of biodegradable plastic materials. Their conception of eco-friendly packaging concerns market appeal and what occurs after consumption (such as degradability, recyclability, renewability, awareness, market penetration availability, and price).

Biodegradable’s market share and success rates are influenced by their sustainability certifications, clients, resources, governmental regulations, and technology (says Producers number one, two, and three). The price of biodegradable plastics is frequently higher than that of regular plastics. Manufacturers are discouraged by this since it lowers their profit margins. Traditional and recycled plastic titans dominate Malaysia’s plastics sector. They oppose the biodegradable plastics industry in general and consider biodegradable plastics to be a competitive threat (Says producer number one). Therefore, as a dynamic structure, the company reflects on an environment that challenges varied and unusual behaviours when dealing with sustainability. The environment of an organisation involves variables or individuals within (internal) and outside (external) the organisation, which are influenced by the process in some way. Typically, these individuals have vested interests in the organisation’s success.

5.1. Environmental Value

Environmental behaviour is described as a representation of the kinds of interaction developed between the environment and the cultural aspects. “Environmental value is concerned with the generally consistent concepts about topics such as the population limit that the planet is approaching and the link between the sustainable development held by the general public”. As a result, according to NGO1, customers’ use of environmentally friendly products is motivated by a feeling of social duty. This behaviour is the outcome of concern for the environment. Several researchers, including [36,37], have studied and verified the validity of values and their link to environmental concerns behaviour. NGO2 highlighted that consumers’ environmental considerations are one of the factors that influence their ecologically responsible behaviour. According to P2, a sense of duty toward the environment is one of the most beneficial elements for sustainability behaviour among Malaysian consumers. Because of this, “customers who are more concerned about the environment than the ordinary consumer are more inclined to embrace and buy environmentally friendly products”.

5.2. Perceived Benefits

Sustainability’s behavioural intention is to consider preserving the planet for both the present generation and future generations to improve such aspects. In order to enhance sustainability behavioural intention, a product’s perceived benefit must have several features related to consumer views of the product’s value. According to Gounaris et al. [38], customers’ purchase intentions were positively affected by perceived value. People are more likely to purchase products when they believe their value is high. According to NGO number one responses, customers place a high value on perceived value, and firms must grasp this to gain a competitive edge in the marketplace. A crucial aspect of achieving and maintaining a competitive edge in a hyper-competitive market is creating and transferring value to the customer. Because perceived value substantially impacts consumer happiness, trust, and behavioural intentions, examining its aspects might help firms better understand their customers’ needs [39]. The results of a more in-depth investigation of the consumer value of various environmentally friendly items demonstrate that, in most cases, customers do not reap any immediate benefits from a product’s lower environmental effect. In most circumstances, improvements in environmental quality are the only benefit to customers when substantial portions of the global population engage in generalised environmentally friendly purchasing behaviour. According to producer number three, currently, consumers are concerned with protecting the ecosystem and sustainable growth. However, there is also a paradox of individuals having supportive attitudes to nature in the scope of environmental protection but attempting to demonstrate negative environmental behaviours.

5.3. Regulatory Pressure

By offering incentives to encourage polluting firms to minimise pollution, the regulatory approach attempts to avert environmental concerns. The incentive-based strategy has the advantage of encouraging the development of creative and affordable pollution control techniques. External pressure is a major factor in environmental activities, and different external pressures can result in various internal organisational reactions. Following government agency number four replies, legislative push and demand-pull have been recognised as the most critical external determinants of sustainable behaviour intention. Following government agency number three responses, concerns about sustainable growth and environmental preservation are among the greatest challenges organisations face today. It is possible that the introduction of new or enhanced legislation relating to products and waste disposal would make it essential for organisations to recuperate used products that they have manufactured or to take them back after the product has reached the end of its usable life span. Regulations are typically seen as having the largest impact on a company’s ability to conduct sustained operations. Governmental and nongovernmental organisations pressure organisations to implement environmentally sustainable strategies by enacting measures to protect the ecosystem (Says government agency two). This motivates competitors to introduce green policies in their own businesses. Government legislation is also effective for restricting a company’s operations, increasing manufacturing prices, and prompting technology investigations, which must follow defined requirements [40]. Finally, influential customer companies could use their power to change the production activities of their manufacturers to meet their specifications.

5.4. Environmental Knowledge

Participants also speculate that environmental consciousness may influence consumers’ perspectives and preferences regarding biodegradable plastics. Understanding the environment is crucial for making decisions about their life, including what to buy [41]. Rajendran & Wahab [42] claim that environmental information is applied throughout the customer’s product evaluation stage, when their appraisal of items may result in favourable or unfavourable decisions and judgements. Moreover, consumer perception is a sort of environmental knowledge essential for helping customers examine or evaluate their purchase behaviours [42]. Additionally, the more knowledgeable consumers are about eco-products, the more favourably they perceive them, enhancing their desire to purchase them (Says producer number two). As a result, it is acknowledged that environmental awareness is crucial for altering attitudes and intents. According to Klein et al. [43], customers’ decisions to buy green items were impacted by their understanding of the environment (biodegradable plastic). This demonstrates that customers’ intellectual responses to a product’s environmental qualities are represented by ecological knowledge. In terms of product environmental factors, the effects on the environment are more potent and have a greater emotional impact [44].

5.5. Social Norm

In order to achieve group goals and maintain communal activities, social norms are the rules and standards that govern or regulate the behaviour of group members [45,46]. Social norms are based on informal social sanctions or rewards that guarantee desirable behaviour is observed, as opposed to the obligatory legal system [47]. Social norms are behavioural standards that have progressively evolved through social interaction and experience and are used to control people’s actions to preserve social order. Descriptive norms are behavioural standards created by the activities of the majority of a group’s members, such as “75% of consumers have already made green consumption”, according to Farrow et al. [48]. Descriptive norms can be used to describe acceptable or unacceptable (prohibited) behaviour. People may learn more about descriptive norms by looking at examples of the best, safest behaviours in various contexts. Compared to other information, this information is connected to accomplishing efficient personal objectives and is more likely to excite the person’s heuristic information-processing mode.

5.6. Personal Norm

Thøgersen [49] describes personal norms as “feelings of moral responsibility to execute or refrain from certain behaviours”. Personal norm is “used to denote the self-expectations for specific conduct in particular contexts established by the individual” [50]. Having apprehensive behaviour is a personal norm, which is a moral duty that individuals have [51]. According to previous research [52,53], personal norms are among the most powerful influences on customer behaviour. According to Prakash and Pathak’s [54] research, personal norms are associated with a customer’s purchasing intention.

Furthermore, personal values significantly shape Danish customers’ ecologically friendly behaviour [55]. It is well accepted that personal norms are a key determinant of consumer behaviour. Like politics, religion is essential in shaping people’s attitudes and actions [56]. Personal norms that have been activated are associated with sentiments of moral duty. People with strong personal norms to operate pro-environmentally feel morally obligated to do so in the environmental sphere [57]. In accordance with this, Stern et al. [58] asserted that pro-environmental conduct is connected with personal norms. This suggests that the stronger the moral imperative to act pro-environmental, the greater the number of individuals participating in pro-environmental behaviour [59].

5.7. Perceived Risk

Perceived risk is the possibility of a negative outcome occurring as a result of purchasing a product and is determined by the consumer’s judgement of the likelihood of such an outcome occurring. Consumer scepticism about green products may be reduced by lowering the customer’s perceived risk [60]. This may increase customer trust in green products [61]. The evaluation of perceived risk would influence a consumer’s purchasing decision since the perceived risk is a combination of undesirable consequences and uncertainty [62]. According to previous studies, consumers’ perceptions of risk influence their buying decisions and behaviours [61,63,64]. According to the perceived risk theory, consumers are more concerned with minimising their perceived risk than maximising their benefit [61]. Because of the information asymmetry, it is more difficult for purchasers to determine a product’s true worth before making a purchase [65]. As a result, the supplier is incentivised to engage in dishonest business practices [64]. As a result of the asymmetry of environmental knowledge between consumers and sellers, purchasers eventually become hesitant to acquire a product owing to their mistrust of the retailer.

5.8. Ascription of Responsibility

Edenbrandt et al. [66] define the ascription of responsibility as “the sense of personal responsibility for the difficulties”. According to Ebreo et al. [67], attributed guilt significantly predicted behaviour concerning the surroundings. According to the research, when the responsibility is placed on one’s own person, they are more likely to engage in waste reduction behaviour. According to Vaske et al. [68], a study on carbon footprint reduction revealed that an increase in the ascription of responsibility leads to an increase in reported environmental behaviour, favouring personal norms. De Groot & Steg [69] postulated that the assignment of responsibility would have a favourable impact on personal norms in light of their numerous research on pro-social intention. Prior studies have shown that assuming responsibility positively affects individual norms and intentions, especially in the area of environmentally beneficial behaviour. Consumers’ intentions to purchase environmentally friendly items are referred to as green behaviour.

5.9. Environmental Attitude

An attitude in response to an outside occurrence is a set mood, feeling, or viewpoint. According to NGO2, “Attitudes can be momentary or evolve into a permanent condition that influences a consumer’s efforts to evaluate a good, service, or anything similar, where they may acquire an attitude towards the object being measured”. The formation of particular behaviours is enabled because environmental factors may alter one’s attitude towards something. The functional definition of attitude is a consumer’s judgement of their likes and dislikes in response to any external stimuli. As established by P3, attitude results from a person’s beliefs about the consequences of their actions and their evaluations of whether or not those consequences would be beneficial. According to P2, currently, consumers are concerned with protecting the ecosystem and sustainable growth. However, there is also a paradox of individuals having supportive attitudes to nature in the scope of environmental protection but attempting to demonstrate negative environmental behaviours. Instead, based on various research that indicated the correlation between attitudes and behaviour, it is reasonable to conclude that an individual’s pro-environmental attitude (such as waste avoiding, recycling, and green consumerism) was significantly associated with the considered pro-environmental attitude behaviour. They are beginning to shift their buying behaviour to express their sympathy towards the environment and exercise a green attitude, says P1. This concludes that changes in attitudes can lead to a change in behaviour.

5.10. Sustainability Behavioural Intention

When referring to the elements that impact a certain behaviour, the term “sustainability behavioural intention” refers to considering the necessity of preserving the planet for both the present generation and the generations to come to improve such aspects. The more fervently one intends to act, the greater the likelihood that the purpose will be realised. According to the point of view of government agency number four, increased population growth, industrialisation, and economic development have contributed to increased demand for natural resources over the last few centuries. This has harmed the ecological systems of the planet as well as the environmental quality of human health. In today’s world, terms such as “climate change”, “sustainable”, and “green” have made their way into the vernacular, along with innovative strategies for coping with the negative effects of climate change [70]. The World Commission on Environment and Development of the United Nations defined sustainable development as “the implementation of sustainable behavioural patterns that would address the needs of the present generation without jeopardising future generations’ ability to meet their needs”. As a result, many environmental management and sustainable development initiatives can trace their roots back to this commission [71]. This suggests that for consumers to embrace sustainability measures, they need to investigate their individual consumption patterns’ impact on the surrounding environment and the generations that will come after them. Then, they need to adjust their lifestyles by selecting green or sustainable options and reducing their consumption levels by consuming less.

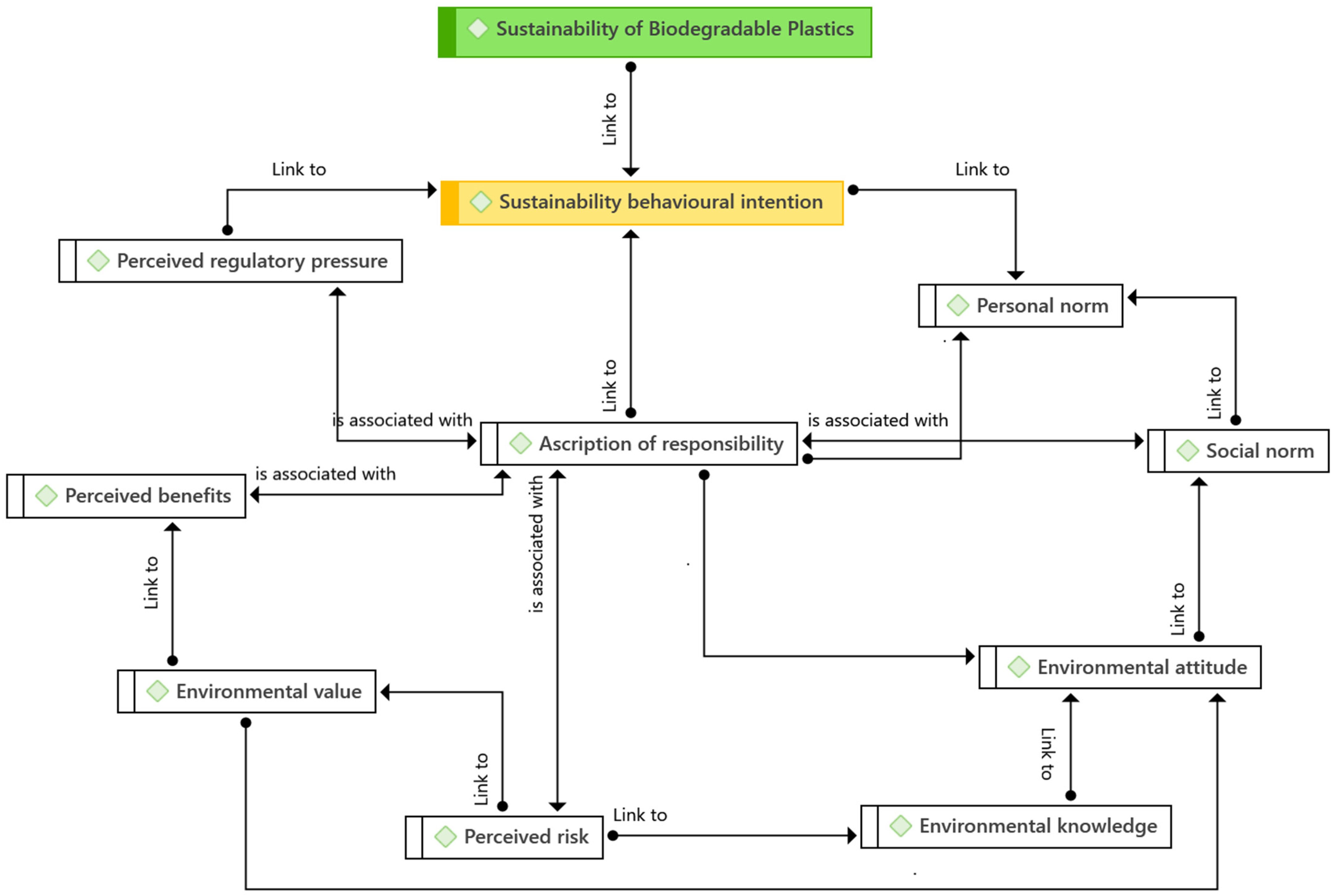

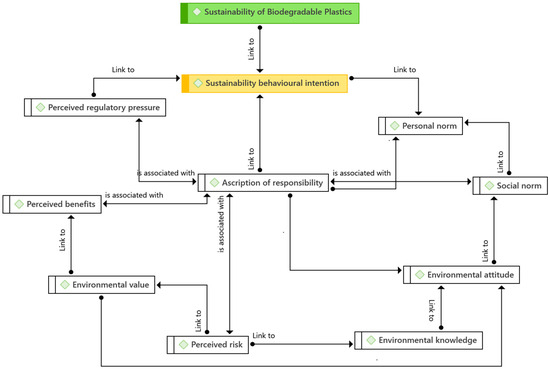

Experts actively seek solutions to environmental difficulties in this situation and are very worried about general health welfare [72]. Environmental consumerism and environmentally friendly products are two essential behaviours associated with environmental consciousness, as stated by Arısal & Atalar [73]. Use of energy-efficient light bulbs, household items with low energy consumption that may be recycled or repurposed, scents free of non-biodegradable chemicals, post-consumer garbage or plastics, and products manufactured from biodegradable materials are just a few examples. For many years, there has been fierce debate about biodegradable polymers. One side fervently favours the idea, while the other dismisses it as a fantasy with little chance of coming true. In addition, producer number one asserts that the advent of biodegradable plastic, also known as biodegradable plastic, is meant to solve environmental issues brought on by non-biodegradable plastics. This demonstrates how attitudes are shifting, with many planning to use biodegradable plastics rather than non-biodegradable ones. Figure 1 illustrates the characteristics that influence the demand for biodegradable plastics among consumers.

Figure 1.

Organisational factors influencing demand for biodegradable plastics.

5.11. Sustainability of Biodegradable Plastics

Numerous difficulties confront the manufacturers of biodegradable polymers. However, little research has been conducted to specifically analyse these challenges [74,75]. The researcher discovered some surprising things regarding the main challenges businesses face while developing biodegradable plastic goods via our contacts with the study’s enterprises. In order to begin with, it was found that a significant challenge in developing green products is fusing environmental and conventional product attributes. According to producer number two, delivering at a fair price is another problem. There are green alternatives for things like plastic, gasoline, cars, paper, ink, leather, and others, but they are too expensive to win over an industry or most consumers. Because of high research and manufacturing costs that make green products’ pricing uncompetitive, the adoption of green products is still being held up in several industries. According to producer number three, competing in many market areas is challenging against companies and brands that have not adopted green technology without government rebates and subsidies for businesses and consumers. Economics is another issue, according to the third producer, who said, “We are at a disadvantage when comparing plastic and biodegradable plastic pricing… We get no grants…”. To eliminate pollution, “our customers must pay taxes; the playing field is far from even”. Along with the price, other crucial aspects of environmental sustainability should be considered, including product quality, aesthetics, and claim believability.

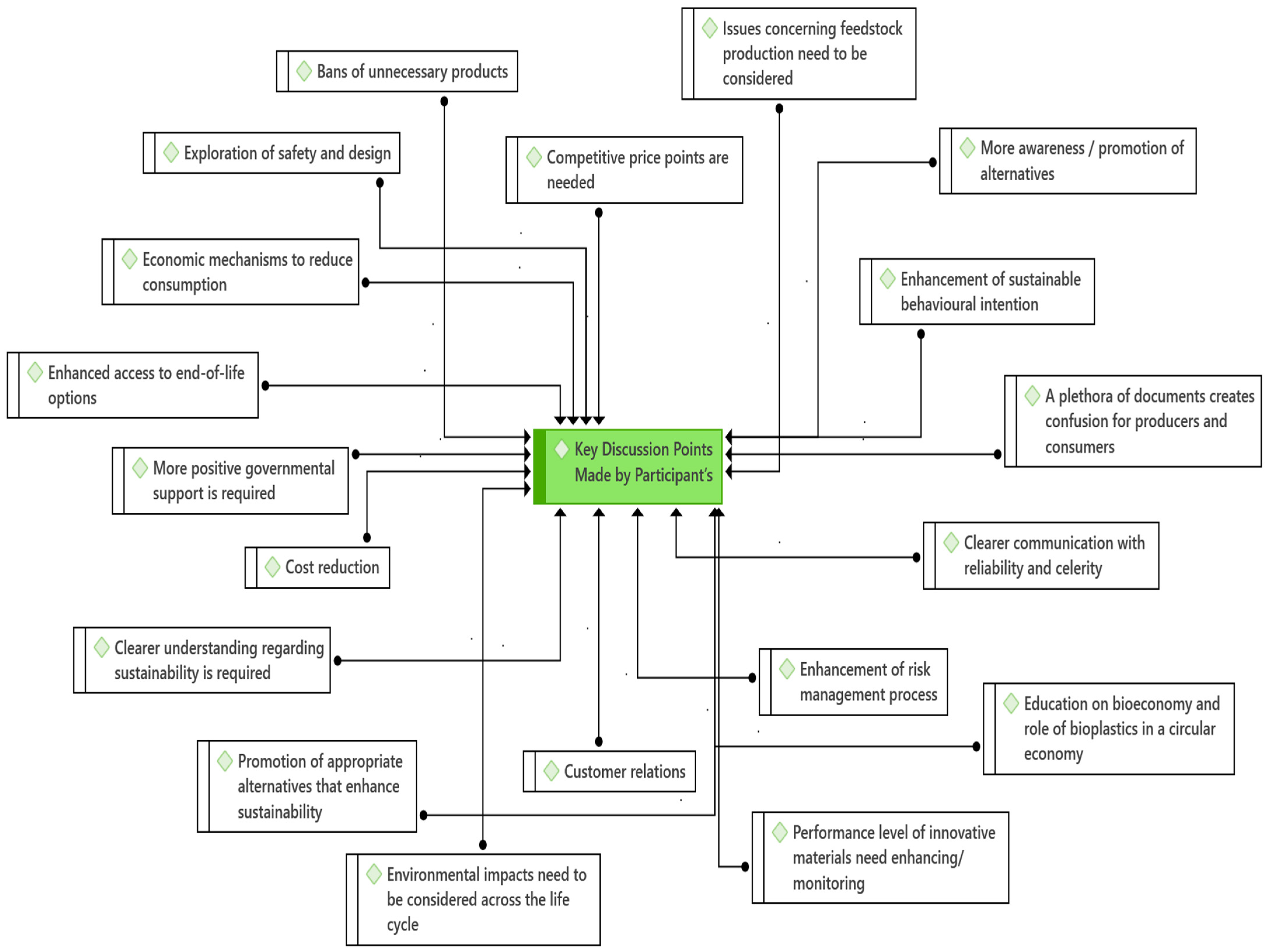

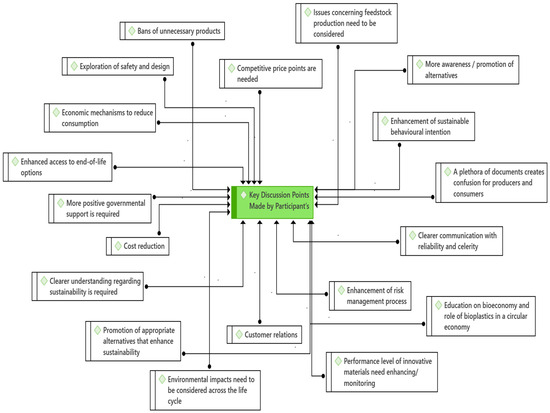

One major issue for companies that produce and promote biodegradable plastic materials is that customers do not understand the benefits of these products, as stated by NGO number one, who admits that “many people aren’t even aware… mass awareness isn’t there in the market…awareness is one of the important obstacles”. Producer three chimes in: “The buyers don’t realise the value of the enhanced sustainability of our products”. The market is unaware of the benefits of eco-design, such as waste minimisation. The toughest challenge is finding a way to use the response to climate change to one’s economic benefit in the long run. As an alternative, eco-labelling or third-party certification can help overcome client ignorance by identifying green products and establishing the authenticity of green promises. The challenges brought up by interviewees are highlighted in Figure 2, along with which policy tools should (theoretically) be applied to solve them.

Figure 2.

Overview of the critical concerns raised by the participants.

Another topic of discussion was how to organise and oversee resources both within and outside the product team, which is especially important for companies seeking third-party certification or an eco-label. The eco-labelling process can be lengthy, and working with several parties requires strong organisational abilities. This procedure is anticipated to go more smoothly as ecological specialists are increasingly included in the development and product design processes (says producer number one).

During our conversation, questions about government policies were also brought up. The pricing is the pull factor or the push factor for every new technology or product, according to producer number one: “There is no policy in Malaysia that encourages biodegradable plastic goods”. In order to make sure that all stakeholders are aware of the potential advantages of the biodegradable plastics industry, governing bodies should apply both push and pull factors. For instance, the pull factor is tax incentives for biodegradable plastics enterprises, whereas the push factor is laws banning single-use plastics. “Using electric automobiles as an example, before Tesla’s innovation, electric cars were unaffordable, but now they can be purchased for various prices… depending on the model” (says producer number three). What factors, then, encourage the adoption of such cutting-edge technologies? Government regulations must be passed, along with encouragement through tax breaks or other financial aid. “There is no law or regulation mandating the use of biodegradable polymers in substitution of non-biodegradable plastics” (says producer number three). There is no requirement to utilise biodegradable plastics in that legislative act, and therefore, if that is the case, businesses will choose the most lucrative course. That is the main justification, in my opinion.

People are already good at creating new policies. However, if a law is not upheld, it does not exist. A policy cannot be considered a law if it is not upheld. If there is no enforcement, it remains a policy document. Academics have suggestions for the Malaysian people but will not leave until they are implemented. It is just a collection of ideas. It is crucial to comprehend how company objectives and guidelines for creating biodegradable plastic products are created and presented. “The environmental goals, objectives, and policies for goods are created following the rules and paying a greater attention to the environment” (says producer number three). As a result, questions have been raised concerning the applicability and accessibility of current papers, which enable companies to swiftly take action to guarantee that they abide by laws and regulations in this situation. In order to address this, it is vital to assess current policies (as well as related materials like standards) to make sure that they are fully applicable and suitable for circumstances involving the usage of biodegradable plastic. In addition, it is important to provide a method that businesses can use to find, apply, and comply with policy papers that is simple to use, reliable, and consistent. This problem kept coming up during the participant’s engagement activities. The availability and comprehension of regulations and legislation were cited as potential roadblocks to using biodegradable polymers.

The results of this study show that individual circumstances significantly affect the sustainability of biodegradable polymers. Nevertheless, mixed results have been obtained due to conceptualisation discrepancies across these structures and the effect of the research setting. The results of this study also showed the necessity of evaluating the link, as mentioned above, in the dynamic and unpredictably changing biodegradable plastic industry. The structure, strategy, and performance of biodegradable plastics towards sustainability have only recently been examined via minimal studies into operations and behavioural intention towards sustainability, despite the industry’s commitment to global economic growth.

As a result, the researcher’s objective in the second phase (quantitative study) is to create a systematic method for assessing various aspects of the sustainability of biodegradable plastics. This technique will be created and standardised to make it easier to integrate systems and use various models to analyse and rate particular elements. The Malaysian instance will validate this technique and learn what Malaysians think about the sustainability of biodegradable plastics. It was therefore suggested that the goal be to research the specific influences of various aspects on the sustainability of the connection of biodegradable plastics in the Malaysian setting.

Sustainability Principles Identification for Biodegradable Plastics

Sustainability principles identification for biodegradable plastics is one of the key measures for modern management, emphasising sustainable development. Triple bottom line (TBL) theory usually differentiates three dimensions for biodegradable plastics sustainability assessments: economic performance, social responsibility, and environmental protection.

- Economic Impacts of Biodegradable Plastics

The first measure to be involved in ascertaining biodegradable plastics’ sustainability measures the financial implications of the use of the product and the technique adopted in the production of biodegradable plastics [76]. Provisions of good remunerations and a safe environment for work are the techniques that can be used to ensure sustainable manufacturing methods [77]. In order to provide the economic impacts of sustained biodegradable plastics, it should be evaluated through strategies that can preserve cost-effectiveness, environment, human, and social capital for a very long time. The capital strategy will provide the theoretical strategy for measuring all shared resources in various units, which will afford stable, hypothetically comprehensive, and policy-relevant assessments among countries [78].

Therefore, the biodegradable plastics industry must retain diverse financial wealth types to attain economic viability—tangible and intangible assets. Equipment, land, structures, inventory, financing, etc., are tangible properties. On the other hand, intangible assets include a reputation for a brand, creativity, ethos, and employees’ tacit skills and talent [79]. Furthermore, the management of immaterial assets is interlinked with social and environmental aspects of sustainability, demonstrating the interlinked existence of the dimensions of sustainability. According to the study by Carroll, Hummel, Leaviss, Ren, Stevens, Everson-Hock, & Michaels [80], the basis for economic resilience is for a corporation to accept other aspects of responsibility, including its legislative, ethical, philanthropic, and environmental responsibilities or its social well-being [81].

- Social Impacts of Biodegradable Plastics

The second component of biodegradable plastics sustainability is that it should be able to assess the influences of goods and techniques on society [76]. The social impact, resource usage, and production system of biodegradable plastics should be evaluated through the populace’s outcomes and the workers’ social responsibilities. The past and present narratives explain that biodegradable plastics are commonly utilised as food packaging, meal provider ware, bags for the shop, yarns, and agricultural purposes [82]. Nevertheless, the only solution to trash is not the compulsory adoption of biodegradable plastics. There should be a strong aversion to and discouragement of littering, either on land or at sea, including any plastics. Proper awareness should be made by informing and educating the public about the appropriate ways of disposing and managing waste. The design of environmentally friendly products should be intentionally aimed at [83].

Biodegradable plastic materials have been created to decrease litter caused by discarded plastics, either biodegradable or as manure substitutes. It has been identified that biodegradable plastics are usually utilised in the packaging of disposables, and they are utilised in agriculture where biodegradability is recommended. The recently better-developed bio-based non-biodegradable plastics (bio-PE and bio-PET) can be utilised in food packaging [82]. There is growing awareness about the societal influence of packaging products made from “Biodegradable Plastics”. Many people are willing to change to an alternative packaging material with a lesser carbon impression or one produced from renewable resources. This situation has been the major motivation to improve biodegradable plastics to decrease plastic waste management in our society [84].

The social dimensions of biodegradable plastics sustainability are also reflected in corporate social responsibility (CSR) and are sometimes used interchangeably as “social sustainability” and as “CSR”. Trendafilova, Babiak, & Heinze [85] described CSR as “the company’s continuous contribution to ethical actions and contribute to economic growth while increasing its quality of life as well as the local and social communities at large. Equity issues are the core goals of minimizing poverty and increasing the health of developed nations”. So, social sustainability addresses a human’s cultural, economic, social, and emotional needs [86]. Societal capital tackles topics related to culture or communities, such as poverty, inequality, human rights, corruption, community development, welfare, family concerns, lack of schooling, public health, youth activity problems, and democracy. Developing corporate capital encourages trust in the company and its stakeholders, thus enhancing its credibility with its stakeholders [81].

- Environmental Impacts of Biodegradable Plastics

Another element involved in the sustainability of biodegradable plastics is measuring its influence on the environment due to using natural resources such as unrefined materials, energy, and landed property to produce biodegradable plastics. The process involves manufacturing plastic products capable of causing Greenhouse Gases (GHGs), tough liquid waste, air contamination, water contamination, and lethal substances [87]. The measurement of biodegradable plastics’ sustainability relating to the environment can be carried out by monitoring depleted resources and technological pollution while manufacturing products or services [82]. While the depletion of resources comprises usage of the land, usage of energy, usage of water, the use of fossil fuel, etc., the emission of the effluence consists of a change in climate, GHGs, contamination of water, contamination of the air, the release of a lethal substance, poisoning human, the release of cancer-causing agents, summer smog creation, acidification, eutrophication, etc. Assessment of the environment through strategic means is critical to creating sustainable products and services [88]. This strategy will ensure the development of policies, procedures, and packages that are sensitive and favourable to the environment [81,89].

The emphasis is on controlling the harmful environmental effects of company activities regarding ecological sustainability. According to Kopnina [90], in recent research on environmental sustainability, unrestrained economic development is one of the most significant risks to the natural world and ecological processes. Kasayanond, Umam, & Jermsittiparsert [91] describe environmental sustainability as protecting and renewing against recent and potent environmental dangers such as climatic change, global warming, pollution, erosion, and biodiversity depletion, which are global issues. Consumers are rapidly pressuring businesses to implement environmentally sustainable policies to boost efficiency [92].

The biodegradable plastics industry may contribute significantly to addressing increasing environmental issues by incorporating environmentally sustainable activities in their business activities. However, some administrators also find the gains outweighed by sustainable operation costs [93]. According to Morelli, some practitioners view environmental policy as an anti-business activity, hampering a corporation’s productivity and raising short-term production costs [94]. However, many proactive businesses are engaged in enhancing their environmental efficiency. These businesses perceive environmental protection as essential for satisfying different stakeholder groups’ requirements and a basic necessity for gaining a sustainable competitive edge in the marketplace [75]. Döhler et al. [83] proposed a parallel enhancement of environmental sustainability and profitability through environmental programme investments. They also argued that well-planned environmental standards could cause inventions that lower or increase the value of a commodity’s overall cost. These advances enable industries to use various inputs from raw materials to electricity and labour, thereby offsetting the expense of improvement and breaking the stalemate. Ultimately, increased capital efficiency renders firms more competitive than less competitive.

6. Related Theory and Hypotheses Development

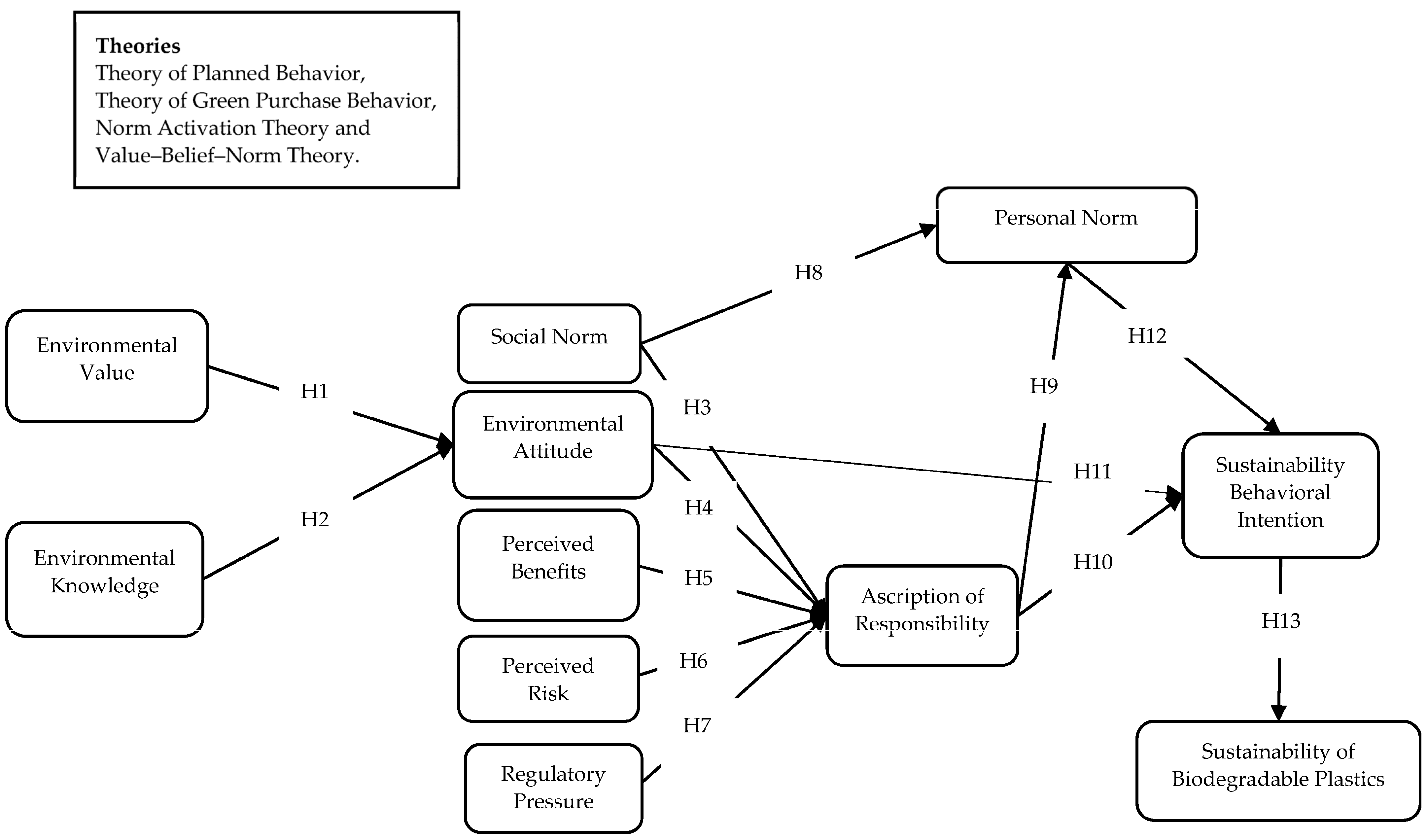

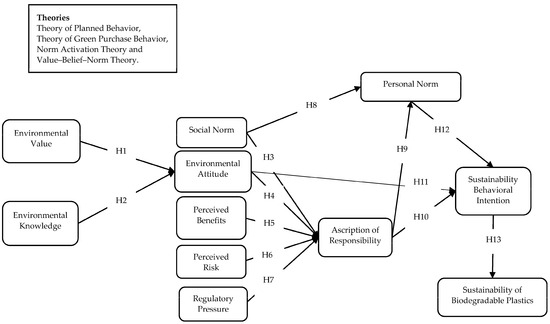

Green consumer behaviour is often viewed as altruistic by researchers who employ the value-belief norm theory (VBN), such as Choi et al. [95] and Nguyen et al. [96]. Others, such as Arli et al. [97], Khare [98], Prakash and Pathak [54], and so on, employ rational choice models like the theory of reasoned action (TRA) or the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) to explain such behaviour since they view it as self-interested. From the study’s multifaceted vantage point, sustainable prosocial behaviour is influenced by both internal and external factors [99]. Developing a holistic model that considers both internal and external elements is essential for analysing sustainable behaviour. This study’s theoretical underpinnings are based on the four guiding paradigms of the theory of planned behaviour, the theory of green purchasing, the theory of norm activation, and the theory of value and belief norms [100]. The unique contribution of this research is that it expands not only the extended theory of reasoned action, the theory of planned behaviour, the theory of green purchasing behaviour, and the theory of value beliefs and norms. As illustrated in Figure 3, this method takes into account the components of the theories of planned behaviour, green purchase behaviour, norm activation, and value–belief–norm to generate a list of variables to include in the proposed study model.

Figure 3.

Theoretical framework.

Hence, the following hypotheses were developed based on the strong evidence provided by the literature considering the individual factors influencing the sustainability of biodegradable plastics in Malaysia.

H1.

There is a positive effect of environmental value on the environmental attitude.

H2.

There is a positive effect of environmental knowledge on the environmental attitude.

H3.

There is a positive effect of the social norm on the ascription of responsibility.

H4.

There is a positive effect of environmental attitude on the ascription of responsibility.

H5.

There is a positive effect of perceived benefits on the ascription of responsibility.

H6.

There is a positive effect of perceived risk on the ascription of responsibility.

H7.

There is a positive effect of regulatory pressure on the ascription of responsibility.

H8.

There is a positive effect of the social norm on the personal norm.

H9.

There is a positive effect of the ascription of responsibility on the personal norm.

H10.

There is a positive effect of the ascription of responsibility on the sustainability behavioural intention.

H11.

There is a positive effect of environmental attitude on the sustainability behavioural intention.

H12.

There is a positive effect of the personal norm on the sustainability behavioural intention.

H13.

There is a positive effect of sustainability behavioural intention on the sustainability of biodegradable plastics.

7. Research Method 2—Online Questionnaire

This part lays out the plan for the second-stage quantitative research study. Quantitative research is where you will most often find a survey employed [101]. Phase two data collection was planned based on an evaluation of the study’s design. In correlational research, surveys are frequently used to collect individual responses that reveal their ideas, beliefs, and attitudes [102]. A survey assists researchers in verifying facts, estimating correlations, and making predictions based on the study’s aims and objectives. In order to better understand the relationships between antecedents and environmental behaviours, some studies have employed survey approaches.

Furthermore, surveys performed in person or over the phone lack anonymity. This is where online-based surveys excel because they may provide anonymity to participants [103]. In addition, online surveys provide several benefits, such as the convenience of collecting data and the timeliness of obtaining responses [104]. This research approach was used to give descriptive data on the profiles of organizational variables on the sustainability of biodegradable plastics in Malaysia to identify the state and standards of biodegradable plastics in Malaysia.

7.1. Questionnaire Design

Firstly, rating scales are a prominent technique in environmental research [105]. Second, a scale’s range of potential answers varies, and textbooks on the subject often depict the most prevalent 5- or 7-point versions [106]. Third, all scales utilised to measure the researched components in this study were of the 7-point Likert type. Fourth, scales derived from well-known instruments were revalidated for face validity and reliability and concept validity and reliability.

A self-administered online survey was employed in the second part of this study. A well-designed questionnaire can also aid in increasing response rates. Furthermore, responses were judged legitimate if participants comprehended the questions and could readily follow the flow of questions. It is critical to plan the flow of the questions carefully. This was accomplished using an approach Saunders et al. [101] developed for sequencing questions. As a result, research participants arranged questions logically and naturally. Individual factors (environmental value, environmental knowledge, environmental attitude, perceived benefits, perceived risk, social norm, personal norm, regulatory pressure, ascription of responsibility, and sustainability behavioural intention) were asked at the start of the survey. Biodegradable plastics’ long-term sustainability was investigated in response to these concerns. The survey concluded with a series of questions designed to collect demographic data. Before performing the official online survey, a pre-test and pilot test were organised in phase two of this research to ensure the validity of the question sequence. There were 57 questions on the survey, and its completion was estimated to take between 15 and 20 min. The survey questions were designed in Malay and English to allow respondents to reply in the language of their choosing, which enhanced the response rate and ensured that each respondent understood the questions on the questionnaire.

7.2. Population and Sampling Procedures

This research population comprises individuals voluntarily interested in this study in Malaysia. The sampling in this study applies G*power (version 3.1.9.7.) analysis. Sampling can be seen as a research strategy for assigning effective population participants in certain research [107]. Stratified random sampling under the probability sampling technique was chosen. Sekaran [108] acknowledged that the corresponding sampling reflects the same percentage of a collection of thresholds during the survey process. Therefore, G*Power is a way to measure statistical power analyses with various t-tests, F-tests, z-tests, and even similar tests [109,110].

This study’s sample size was calculated by applying [111] rule of thumb. Roscoe notes that this law is perfect for research with a sample of more than 30 and less than 500. In conjunction, Hair, Celsi, Money, Samouel, & Page [112] claimed that the sample size must be numerous times (preferably ten times or more) greater than most variables in the study for all multivariate research. Grover Vriens [113] suggested that a more comprehensive approach was applied to avoid improper sample size and to increase efficiency in calculating the sample size indicative of this study. Thus, roughly 138 minimum sample sizes were utilised in this survey following G*Power assumptions with the population level.

7.3. Data Collection

A post-positivist views the world objectively [114]. According to Scheuren [115], the term “survey” is frequently used to describe a technique of collecting data from a group of people. The online survey began in January 2024 and ended in March 2024. The survey method examines and collects people’s opinions, feelings, and ideas. In survey research, the response rate is the proportion of those requested to participate in the study to those who fill out the survey. Due to the possibility of variation between surveys, there are no set expectations for response rates. In Malaysia, questionnaires were sent to plastic users 20 years or older to obtain a significant response rate for this study. Customers in Malaysia who often used plastic-packed items were targeted by the study, which was carried out via a Google form (i.e., those aware of the negative consequences of plastic pollution). Emails and WhatsApp messages with information on the study and a link to the survey were given to PhD group platforms, Environmental Protection Society Malaysia members, and those who indicated an interest in participating. Only those who consented to participate in the online survey clicked the link and completed the questionnaire. Therefore, participants can opt-out without finishing the survey by doing something as easy as turning off the survey link and closing their web browser window. The prologue to the online survey, which could be accessed via a URL supplied in the survey invitation and the participant information forms sent out with the survey invitation, contained information about participants’ right to withdraw from the study. The data were also presented in the online survey’s preface. SmartPLS software was used to examine a total of 308 completed submissions.

7.4. Description of the Respondent Profiles

This section offers a descriptive analysis of the final sample, which details survey participants’ demographic and behavioural traits. The total dataset had 308 individuals, with 149 men (48.4%) and 159 women (59%) making up the final composition (51.6%). The sample’s gender distribution of men and women indicates the general population (males 49%, females 51%). The sample’s largest age groups, in terms of age distribution, were those between 15 and 40. (51.3% combined). The youthful population of Malaysians, with a median age of 30 years, is defined by the United Nations (2002) as those between the ages of 15 and 40. The majority of participants (53.6%) held bachelor’s degrees or higher, with postgraduate degrees (7.5%) being the most prevalent, according to their educational backgrounds. In total, 8.4% of the population possessed a qualification in a trade, and 20.1% had completed high school. Demographic data on the poll respondents indicated that they had relatively high levels of education, with more than half of the sample having completed a bachelor’s degree or above. This may indicate that most Malaysians with internet access are well-educated. As a result, the sample could not correctly reflect the educational background of the Malaysian population, which is considered a drawback of the research sample. The responses are then split into groups according to whether they are married. The total number of single respondents is 145, making up 47%, while the total number of married respondents is 163, making up 52.9%. The respondents are assumed to be knowledgeable about the topic and competent to participate in this survey based on their demographic profile.

Furthermore, the data are also organised based on the ethnic groups Malay, Chinese, Indian, and others. The total respondents are 158 people of Malay ethnicity, with 51.2%. The Chinese respondents are 85 persons (1.85%), Indians are only 44 persons (0.62%), and 21 persons are from other ethnicities. The respondents from different ethnic groups could be Iban, Melanau, Bugis, Bajau, and others from Sabah and Sarawak. Moreover, the respondent background based on nationality was acquired that all respondents (308 people) or percentages showed 100% of respondents were Malaysian citizens spread across several states in Malaysia.

7.5. Measurement Model Assessment: Construct Validity

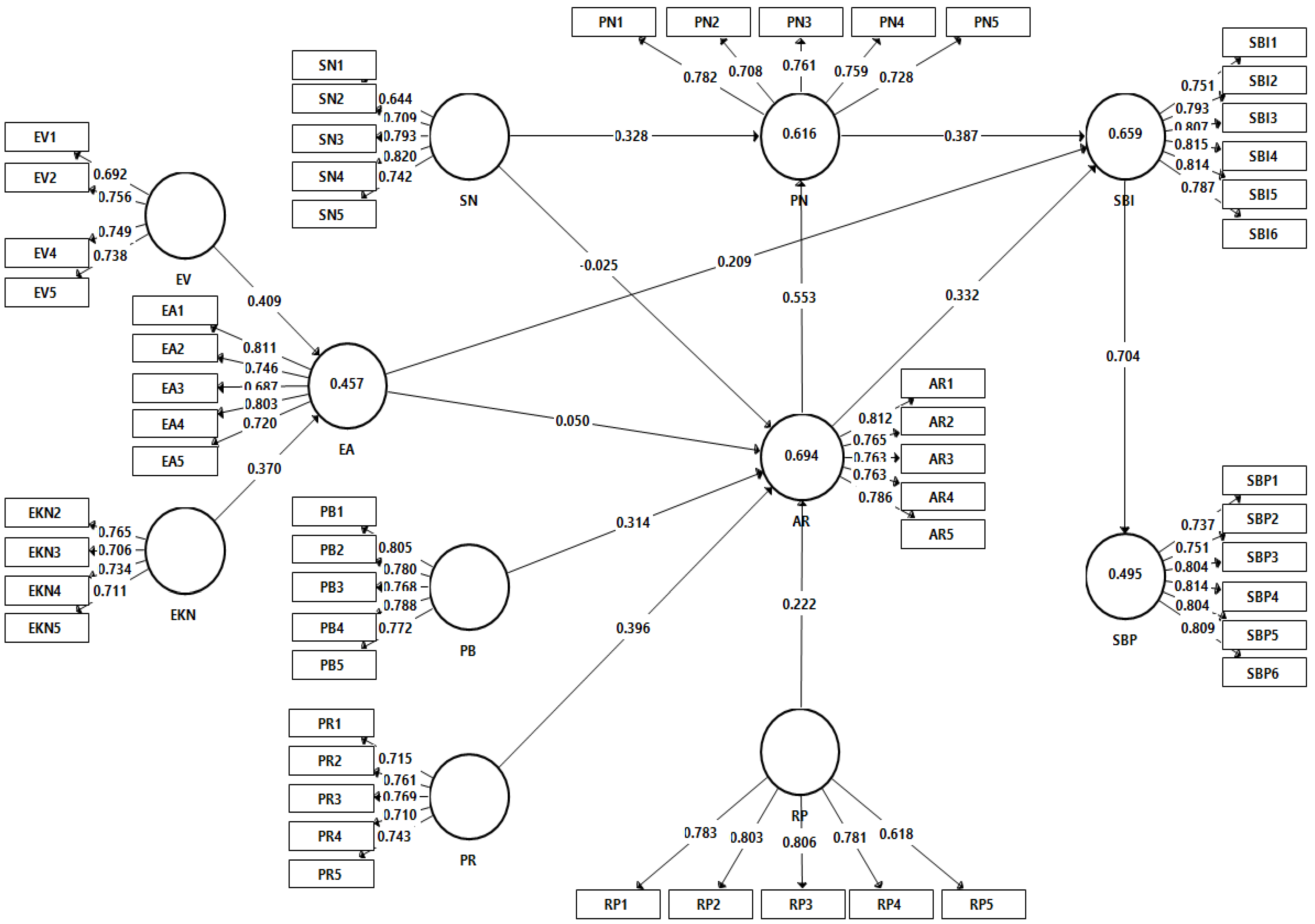

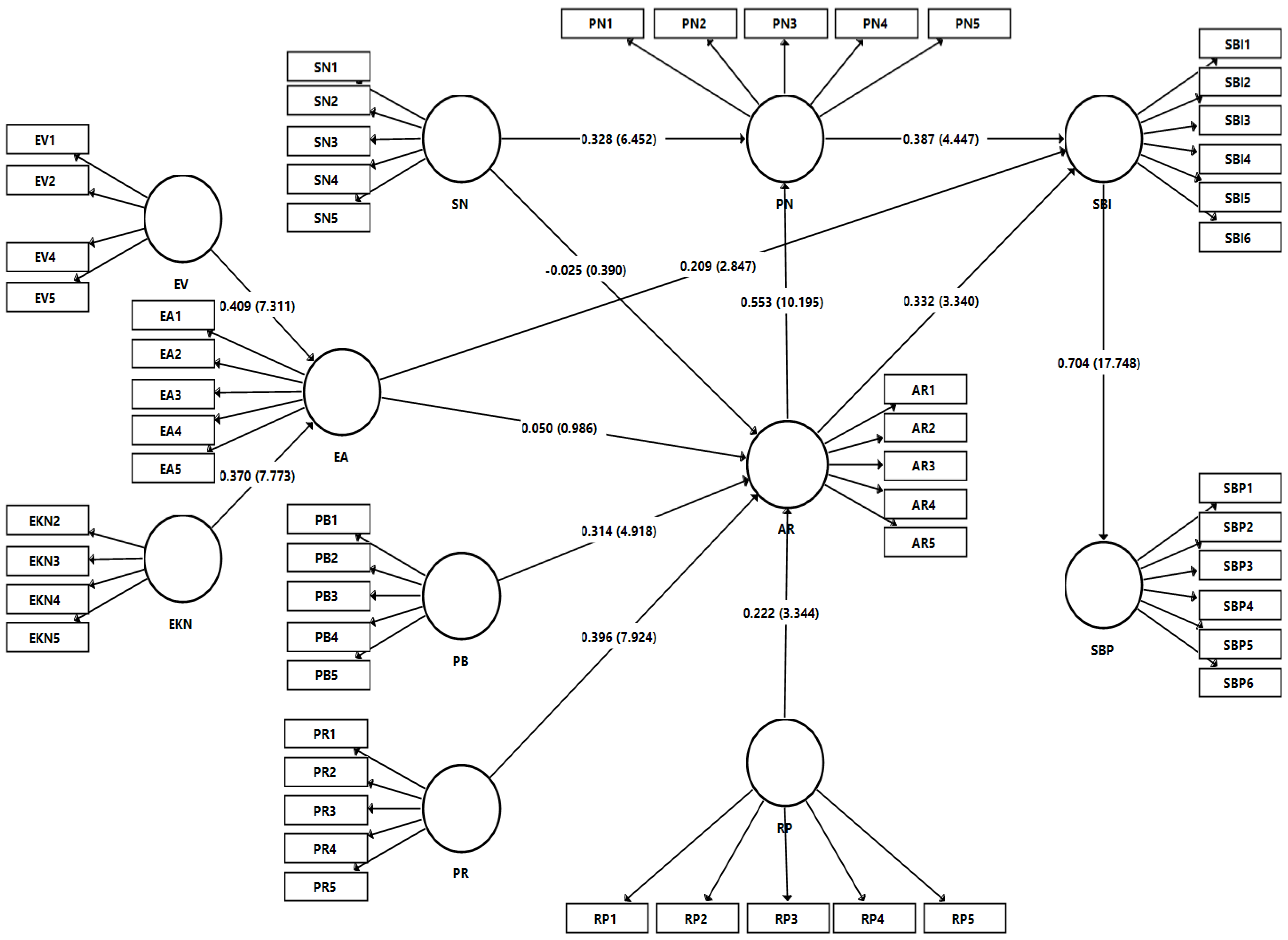

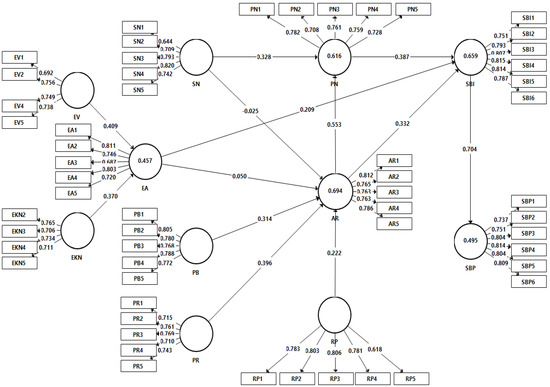

Construct validity is the degree to which a measure reflects the goal variable [116]. The study’s results might be in jeopardy if construct validity is not evaluated [117]. Two different indicators are needed to evaluate a measurement model’s convergent and discriminant validity. A measurement theory was established before the assessment, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

PLS path model.

Convergent validity requires outer loadings, an average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability. The measurement model’s variance for each construct was examined using external loadings, and the reliability of the indicators was assessed using the AVE [118]. Composite reliability was used to evaluate the internal consistency and reliability of each component and their relationship. A summary of the convergent validity assessment is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Convergent validity.

A new method for assessing the discriminant validity of variance-based SEM is the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) [119]. Henseler believes that the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) method is the best suitable for assessing the discriminant validity (DV) of the constructs [119]. In order to achieve DV [120], HTMT values should not exceed either the HTMT.85 value of 0.85 or the HTMT.90 value of 0.90 [121,122]. According to Table 4, no values have been found that have passed both the HTMT.85 and HTMT.90 tests, indicating that the discriminant validity has not been shown. Values of 0.95 and above are thus regarded as problematic.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity: heterotrait–monotrait ratio statistics.

In order to address the problem of a too-high HTMT, Hair et al. [123] suggested that researchers use bootstrap confidence intervals to assess if construct reliability is significantly higher than the required minimum. In order to determine if the HTMT value deviates significantly from 1.00 [119] or a lower threshold value, such as 0.85 or 0.90, which should be chosen based on contextual research, a bootstrap test may be performed. Researchers can assess if the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for HTMT is less than 0.90 or 0.85 in addition to the guidelines mentioned above [124]. As a consequence, as shown in Appendix A, the bootstrap confidence intervals result indicates that the HTMT value is much less than 1.00.

7.6. Structural Model Assessment: Hypothesis Testing

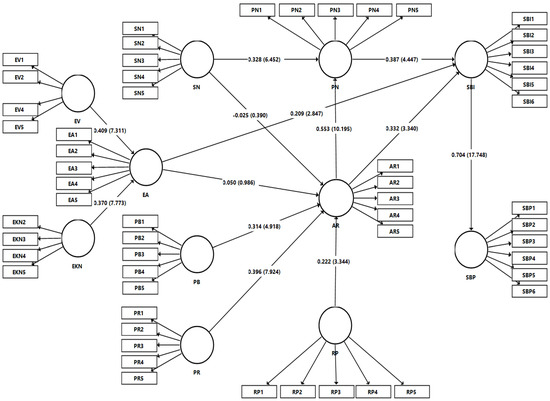

The research team continued using bootstrapping in SmartPLS to determine the hypothesis testing in the structural model after finishing the measurement model assessment and ensuring that the results adhere to all requirements. The researcher must do the bootstrapping with a sample size of 5000 and a significant alpha of 0.05 [125]. The researcher should also evaluate the Standard Coefficients Beta (Standard Beta) to see how one essential variable influences another variable [126]. The researcher cannot automatically conclude that the variables correlate significantly even if the outcome is positive [127]. In order to validate the hypothesis, the researcher needs to assess the interaction effects (t-value) [127]. Hair et al. [128] discovered that the t-value must be higher than 1.645 (t-value > 1.645) for the hypothesis to be accepted when the p-value is less than 0.05 and the one-tailed test is performed. Figure 5 and Table 5 display the outcomes of the hypothesis testing required by bootstrapping.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of structural model through PLS bootstrapping.

Table 5.

Summary of hypotheses testing.

Eleven of the thirteen research hypotheses that have been developed, as shown in Table 5, have significant connections that point in the hypothesised directions. With (=0.409, t = 7.311), the study demonstrates a strong relationship between environmental value and environmental attitude. With a value of (=0.370, t = 7.773), environmental knowledge and attitude have a positive connection. H1 and H2 are therefore supported. Additionally, the study demonstrates that social norms have a negative impact on how much blame is assigned (=−0.025, t = 0.390). H3 is thus not supported. With (=0.050, t = 0.986), the study similarly shows that the environmental attitude aspect has no discernible influence on attributing blame. H4 is thus not supported. The link between perceived benefits and the assumption of responsibility is positive, with a value of (=0.314, t = 4.918), and the association between perceived benefits and the assumption of duty is substantial, with a value of (=0.396, t = 7.924). Consequently, H5 and H6 are well supported. The analysis provides significant evidence for the remaining six hypotheses (H7–H13). Below is a description of the study results from hypothesis testing.

7.7. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

The R-square has been established in the literature as a measure of how much variation in the endogenous variable is analysed by its exogenous variable. The R-square displays the calibre of the variables included in the model [129]. The degree of R-square may be calculated using several variables, and these variables can be used as guidelines. For instance, Chin et al. state that an R-square value of 0.67 or above is deemed significant, 0.33 is considered moderate, and 0.19 is considered weak Chin et al. [130]. Table 6 depicts the R-squared values of the endogenous latent variable (ascription of responsibility, personal norm, environmental attitude, sustainability behavioural intention, and sustainability of biodegradable plastics).

Table 6.

Variance explained in the endogenous latent variable.

7.8. Effect Size

According to Hair and his co-author, researchers have reported on the predictive importance of impact size (f2) and basic traits [128]. Cohen’s [131] criteria state that the impact size must be less than 0.02 (0.10 to 0.14 = moderate, 0.15 to 0.34 = medium, and 0.35 and above = strong). According to Cohen’s criteria, the f2 was assessed; values between 0.10 and 0.14 indicated a small effect, 0.15 and 0.34 indicated a medium effect, and 0.35 and above indicated a strong effect [131]. All eleven factors were examined for f2, summarising the findings in Table 7.

Table 7.

Effect size.

7.9. Assessment of the PLS Predict

PLSpredict is a novel feature that allows researchers to evaluate the prediction power of a model outside of the sample [132]. The sample data are divided into k folds using PLSpredict, each around the same size as the sample data. The method produces a training sample after combining the k-1 folds, which is used to calculate the model’s parameters [132]. Utilising the data from this fold, the remaining fold is used as a holdout sample to assess the predictive potential of the model [133]. In other words, the holdout sample includes the cases for which forecasts will be made using model parameters calculated from the training sample. This process is repeated until each k fold has served as a holdout sample for the fold before it. However, depending on the sample size, the default number of folds (k) is often 10. However, this amount might be adjusted to either be higher or lower. According to Hair et al. [132], the model has weak predictive power if all of the item differences (PLS-SEM value) were higher than LM, medium predictive power if most of the item differences (PLS-SEM value) were lower than LM, and no predictive power if all of the item differences (PLS-SEM value) were higher than LM. The PLSpredict is shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Construct cross-validity redundancy.

8. Discussions of Findings

In order to support our hypothesis, we have drawn on several theoretical frameworks which stress the importance of consumer behaviour intention in forecasting the sustainability of biodegradable plastics. Thus, this study presents an integrated model for analysing the sustainability of biodegradable plastics that considers the individual’s internal and external features. This investigation confirmed experimentally the connections between the constructs founded in current theories with prosocial/pro-environmental objectives and the notions of awareness and attitude, social norm, personal norm, and behaviour within the theory of planned behaviour, theory of green purchase behaviour, norm activation theory, and value–belief–norm theory, which served as theoretical foundations for the formulation of this preliminary conceptual research model.

Considering waste management behaviour excels other sustainability behavioural intentions regarding economic and environmental benefits, governments and industries must create empirical methodologies to ensure proper knowledge. The literature on the sustainability of biodegradable plastics is limited, and there is a lack of relevant theoretical models to explain the sustainability of biodegradable plastics. Our research is an early attempt to examine the structural effects of the determinants toward the sustainability of biodegradable plastics. The researcher discovered that the model (individual components) did not explain much about the sustainability of biodegradable plastics (two hypotheses were rejected). Nonetheless, the researchers discovered that several of its components were a good predictor of the sustainability of biodegradable plastics. The aspiration of responsibility was a statistically significant predictor of sustainability behavioural intentions when all other norm activation concepts and environmental sustainability were considered. To put it another way, persons who accept personal responsibility for the consequences of their actions are more inclined to engage in waste reduction activities.

The researcher also feels that it is vital to examine variances in a personal norm based on whether or not they prefer to allocate responsibility for the immediate or distant consequences of their action as suggested by [134]. The researcher measured ascriptions of responsibility concerning social norms, environmental attitudes, personal norms, perceived risk, regulatory pressure, and perceived benefits because the literature suggests that these variables are better predictors of behaviour than other variables, such as age and gender. The study also discovered a statistically significant relationship between several norm activation theory components and sustainability behavioural intention, which is one of the most noteworthy findings. Ascription of duty was positively linked with regulatory pressure, perceived risk, and perceived advantages, to name a few variables. Respondents who anticipated the effects of their activities and those who felt a strong need to engage in environmentally friendly behaviours were more likely to express greater environmental concern than other respondents. This emphasises that environmental education efforts should be focused on making people aware of the consequences of their activities, or the lack of actions, on the environment. Individuals who are exposed to educational materials that include images or scenarios that depict the consequences of failing to reduce waste in family and community settings are more likely to (1) increase awareness of the negative consequences of their actions and (2) feel a strong commitment to implementing sustainability behavioural intentions.

People with these qualities are more likely to demonstrate their sustainability behavioural intention and waste reduction practices in the real world than others. Furthermore, as suggested by the findings, personal norms were associated with sustainability behavioural intentions, indicating that social norms may mediate between environmental attitude and sustainability behavioural intentions. The findings revealed that personal norms are highly connected with societal norms, sustainable behavioural objectives, and the desire to be more responsible. It is possible that personal standards have both direct and indirect impacts on sustainable behavioural goals and that these effects are mutually reinforcing.

The findings also demonstrate that environmental knowledge and environmental value have a statistically significant link with environmental attitude (environmental attitude). This discovery has met all of the assumptions and standards set out by Baron & Kenny [135], and it is compatible with the findings of the study conducted by [100,136]. As a result, the consumer is more likely to take a strong social stance and advocate for the value of green products. Consequently, the study reveals that the greater the level of concern a Malaysian consumer has for the environment, the greater the degree to which they will influence their attitude toward turning green and adopting a green mentality. In terms of the relationship between environmental attitudes and aspirations of responsibility, the results show that there is no path, which contradicts the hypothesis of this study. As a result, the hypothesis was rejected, contrasting with the study findings by Byrka et al. [137]. According to the findings of this study, although Malaysian consumers are already aware of the issue, this information does not affect their attitude. As a result, attitudes will not impact the level of becoming green and allowing people to embrace sustainable behavioural intents. Consequently, the green practitioner and policymaker may utilise this balance to plan and implement a more successful environmental awareness campaign to encourage people to adopt more sustainable lifestyle choices.

Another relationship worth investigating is the relationship between the aspiration of responsibility and sustainability behavioural intentions and the relationship between the remaining norm activation model concepts and sustainability behavioural intentions as predictors of sustainability behavioural intentions. Ebreo et al. [67] showed that both personal and societal norms influence recycling habits and that perceived repercussions increase the magnitude of their impacts. This study provides evidence in favour of this concept when applied to behavioural goals related to sustainability. This means that, as compared to societal standards, the desire for responsibility and sustainability behavioural intents are also connected to the long-term viability of biodegradable plastic. However, it is possible that this link is not direct. The presence of cognitive, emotional, and attitudinal processes between the two variables may make it difficult to establish a link between them. The researcher feels that this work has contributed to their efforts to develop a theoretical model that may forecast the long-term viability of biodegradable polymers.

Furthermore, the researcher discovered intriguing connections between yearning for responsibility and other factors, which can potentially have both theoretical and practical implications. Including an exploratory measure of sustainability behavioural intention proved useful in helping us better understand the relationships researchers discovered in this study regarding the sustainability of biodegradable plastics and other environmental issues.

9. Theoretical Contributions