Abstract

Social media (SM) has become an unavoidable mode of communication for many young people today, leading to increasing importance in exploring its impact on mental wellbeing. This includes exploring the impact on those who may be more susceptible to developing mental health issues due to adverse childhood experiences, such as care-experienced young people. This study consisted of 22 semi-structured interviews with young people from the general population (n = 11) and care-experienced young people (n = 11). Thematic analysis revealed varying effects of SM, including positive effects such as entertainment, inspiration, and belongingness. However, other findings indicated that the design of SM is damaging for young people’s wellbeing. Age and developmental maturity appeared as key factors influencing the impact of SM on wellbeing, with the indication of further protective factors such as self-awareness, education, and certain SM design features. Specifically, care-experienced young people expressed how lived experiences of the care system can have both positive and negative effects on SM use while revealing the complex relationship between care experience, SM use, and wellbeing. These results can be used to inform SM design and policy and to provide suggestions for SM and wellbeing education among the general population and care-experienced young people.

1. Introduction

Social media (SM) platforms are prevalent in the lives of many young people, with research showing that 91–97% of 12–17-year-olds use SM platforms in the United Kingdom [1]. The definition of SM has been debated in the literature and a single, widely accepted definition is lacking [2]. In this research, SM is defined as an electronic platform that allows users to opportunistically connect, interact, and communicate with others. Two groups of young people in the stages of adolescence and early adulthood are explored in this study: those who are care-experienced and those who are not. With the high prevalence of SM use among young people today, it is vital to research the impact social media may have on their mental wellbeing. This is particularly important to explore with care-experienced young people as they are more susceptible to developing mental health issues and can be characterised as a vulnerable population [3]. Past research has offered largely mixed findings regarding wellbeing when investigating the impact of SM [4,5,6] and has mostly consisted of research with the general population, thus neglecting underrepresented populations such as care-experienced young people. So, gathering data from an underrepresented population will be beneficial to the academic literature in developing our knowledge of care-experienced young people’s lived experiences while also hoping to empower these young people to make change and contribute to research. Furthermore, recent systematic reviews [7,8] have suggested the need for more qualitative, exploratory studies on social media and wellbeing, which supports this research’s contribution. Therefore, these research gaps justify the rationale for this exploratory research and demonstrate the necessity to see if, and how, the needs of the care-experienced population differ to those non-care-experienced (as the care-experienced group is notably more susceptible to developing mental health issues), and the implications this has for SM design and policy.

Young people use SM regularly to confirm their role and position in friendship groups [9], and if access to SM is restricted, it is likely to produce anxiety in adolescents [10]. This is thought to occur mainly due to a phenomenon called FoMO (fear of missing out). FoMO is considered one of the biggest driving forces behind greater SM use among adolescents, with emotional investment in SM leading to anxiety about what they may be missing online when they are offline [11]. This results in increasing reliance on SM, greater use, and a higher likelihood of developing anxiety and depressive symptoms [12,13]. This is consistent with other research that outlines the relationship between SM use and dopamine. The persuasive design of SM (the high accessibility, nudges, and other design features that entice the user to keep checking the platform) causes a dopamine rush in the brain, leading to the feeling of reward and resulting in habitual behaviour [14].

Another aspect of SM that seems to have substantial impact on psychological wellbeing is feedback, often in the form of likes, comments, views, and other metrics visible on SM platforms. Li et al. [15] tested a large sample of young people and found that those who placed higher importance on peer feedback on SM posts (especially females) tended to have more symptoms of depression and low self-esteem, which is consistent with other research [16,17]. It has also been highlighted by researchers that SM profiles are often biased, only showing the positive side of life [18]; thus, comparing oneself to a seemingly ‘perfect’ other can result in reduced self-esteem and wellbeing.

On the other hand, alternative findings have suggested that SM can have positive effects on young people’s wellbeing and self-esteem, with research findings showing that Instagram users had lower anxiety, depressive symptoms, and lower levels of loneliness [19]. This could be due to multiple factors, such as SM providing a safe space for the maintenance of friendships, wellbeing, and creating communities to feel a sense of belongingness and social support [20,21,22,23]. In addition, research has demonstrated other positive impacts of SM use, such as relaxation, entertainment, and escapism from daily stressors [24,25]. There have also been findings that suggest some aspects of SM design can reduce the anxiety around being judged negatively and therefore have a positive influence on wellbeing, including ephemeral features like SM ‘stories’ and SM platforms that show fewer feedback mechanisms [26]. Hence, the research is mixed, unclear, and primarily studies the general population, suggesting the need for more exploratory and detailed research.

For care-experienced young people specifically, research has found both advantages and disadvantages of SM use for mental wellbeing. Positive effects include the reduction of isolation and loneliness (especially for care leavers), providing social interaction and support, and creating a community that makes the user feel like they belong [27,28,29]. This is especially important for care-experienced young people given their increased reliance on peers for social support and community [27]. In contrast, there are challenges for care-experienced young people online, including a heightened risk of online grooming, heightened emotional responses to SM content, and concerns for unmediated contact with birth families and thus safety [27,30]. Therefore, SM can be both beneficial and harmful for care-experienced young people, but more recent research is needed to explore the reasons why this may be.

When exploring mental wellbeing in young people, it is important to note that adolescence is a key stage in vulnerability; therefore, age and emotional development may have a significant impact on how SM is affecting young people. Adolescence is a vulnerable period for many aspects of mental wellbeing, such as low self-esteem [31,32]. This is due to multiple social and developmental processes that occur during adolescence, like the heightened salience of social norms, importance placed on friendships, peer feedback and approval, identity development, and increased self-consciousness [33,34,35,36,37]. Therefore, adolescence is a key developmental period to research as it creates questions regarding young people’s vulnerability in developing mental health concerns during this time and how this is impacted further by regular SM use, which can intensify the social and developmental processes mentioned [34].

Hence, the two research questions (RQs) of this study are as follows:

- RQ 1: How does regular SM use impact the mental wellbeing and self-view of young people, and how does this vary between young people who have and have not experienced the care system?

- RQ 2: How do adverse childhood experiences impact resilience to the effects of SM on the mental wellbeing of care-experienced young people?

The RQs were purposefully kept broad so as not to limit participants’ answers, to allow them the freedom to expand on topics, and to discuss what came naturally to them. The aim of this study was to explore the effects of SM on young people’s mental wellbeing to develop our understanding and make suggestions on how SM could be made a safer, more positive place for young people, whilst representing and sharing the lived experiences of an underrepresented population. Also, by exploring two participant groups, there is the further objective of investigating whether there may be differences in experiences of using SM and the subsequent effects on mental wellbeing between young people who have and have not experienced the care system.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used semi-structured interviews to allow for deep, personal exploration of, and discussion around, how SM influences young people’s mental wellbeing. Twenty-two interviews were conducted online using Microsoft Teams. A two-group design was utilised in which 11 young people from the general population and 11 care-experienced young people were recruited, with the intention of exploring how their experiences of SM differed. Recruitment was achieved through snowball sampling and with assistance from Nottingham City Council. Twitter was used to recruit care leavers through searching the hashtag ‘#CEP’ (which stands for care-experienced people) and private messaging potential participants who fell within the 13–25-year age range. Demographic details for the whole sample can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

Full ethical approval was granted by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Nottingham. Ongoing collaborations occurred with Nottingham City Council to ensure the appropriate safeguards were in place. Participants were required to have full parental or carer consent if under 16, or above if the carer felt it necessary, along with their own consent. Information sheets were provided via email and were available via the lead author’s professional webpage. Participants were debriefed at the end of the interview, though they were also provided with the opportunity for continued communication via email for any further questions or signposting to mental health services, if required. Participants were frequently reminded of their right to withdraw from the research and the option to skip questions at any time.

All interview sessions occurred between June 2021 and May 2022, lasted 30–60 min, and were recorded using Microsoft Teams. The study began with the lead researcher explaining what would happen during the study, reminding the participant of their right to withdraw, and ensuring all participants were comfortable. After the interview had concluded, participants were thanked during the debrief and received an Amazon voucher as compensation for their time. Upon completion of the studies, transcripts were generated through Microsoft Stream and anonymised to protect participants’ identity.

A discussion guide was used by the lead researcher, consisting of main questions and prompts. Key questions included broad questions regarding how SM made the young people feel, and then more specific questions relating to social comparison, peer approval, identity, and more. For the full discussion guide used for the interviews, see Appendix A. The guide was followed roughly and used to steer conversation back on track if participants became distracted. Terms such as wellbeing and identity were not pre-defined within the interviews, instead allowing participants to self-define and ask for clarification if required (see Appendix A for examples of clarifying terms). This approach enabled freedom of interpretation for participants and was aligned with the interpretivist approach of allowing definitions to emerge during data analysis, where concepts are influenced by the researcher’s interpretation of the data [38].

Data were analysed using inductive reflexive thematic analysis to explore themes between participants, which allowed flexible engagement with the data [39]. The lead author conducted the analysis from an interpretivist positionality, with the second co-author blindly verifying the analysis. An experiential qualitative framework was adopted to explore the participants’ own perspectives [39], and coding was performed inductively. The analysis broadly followed the step-by-step guide described by Braun and Clarke [39,40]. The lead researcher first familiarized themselves with the data by reviewing and checking all transcripts thoroughly, and then transferring each transcript to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Initial codes were generated inductively to capture meaning, which were then organised in the spreadsheet. Initial groups were created by grouping initial codes according to similar concepts and patterns. The groups were then reviewed and developed into themes and subthemes, being named and defined in keeping with the phases outlined by Braun and Clarke [39,40].

Thematic analyses were conducted separately for both groups of participants. These were compared once themes had been developed for each to explore differences and similarities between them. The analysis process was completed using Microsoft Excel, creating an index system to track each code generated and to allow the corresponding raw data and participant to be easily located after the transcript had been copied to individual spreadsheets (for example, a code generated from line 50 of the transcript from participant A would be assigned the index A50). The lead researcher kept a reflexive journal throughout, as reflexivity is a crucial part of qualitative analysis due to researchers possessing unique positionality in relation to data interpretation [39,41]. This approach therefore enabled awareness of personal influences and is an activity that increases the confirmability and quality of reflexive thematic analysis [39].

3. Results

The reflexive thematic analysis led to the identification of four overarching themes and one group-specific theme. In addition, nine subthemes and six group-specific subthemes were developed. The themes and corresponding participant quotes can be seen in Table 2. When reporting the findings, some information is presented regarding the prevalence of some themes and subthemes among participants. It is important to note, however, that these proportions are just one indicator of prevalence across cases and are not intended to discount any other findings or the lived experience of the participants.

Table 2.

Themes and subthemes found from the thematic analysis. Those placed under one participant group only refer to group-specific findings.

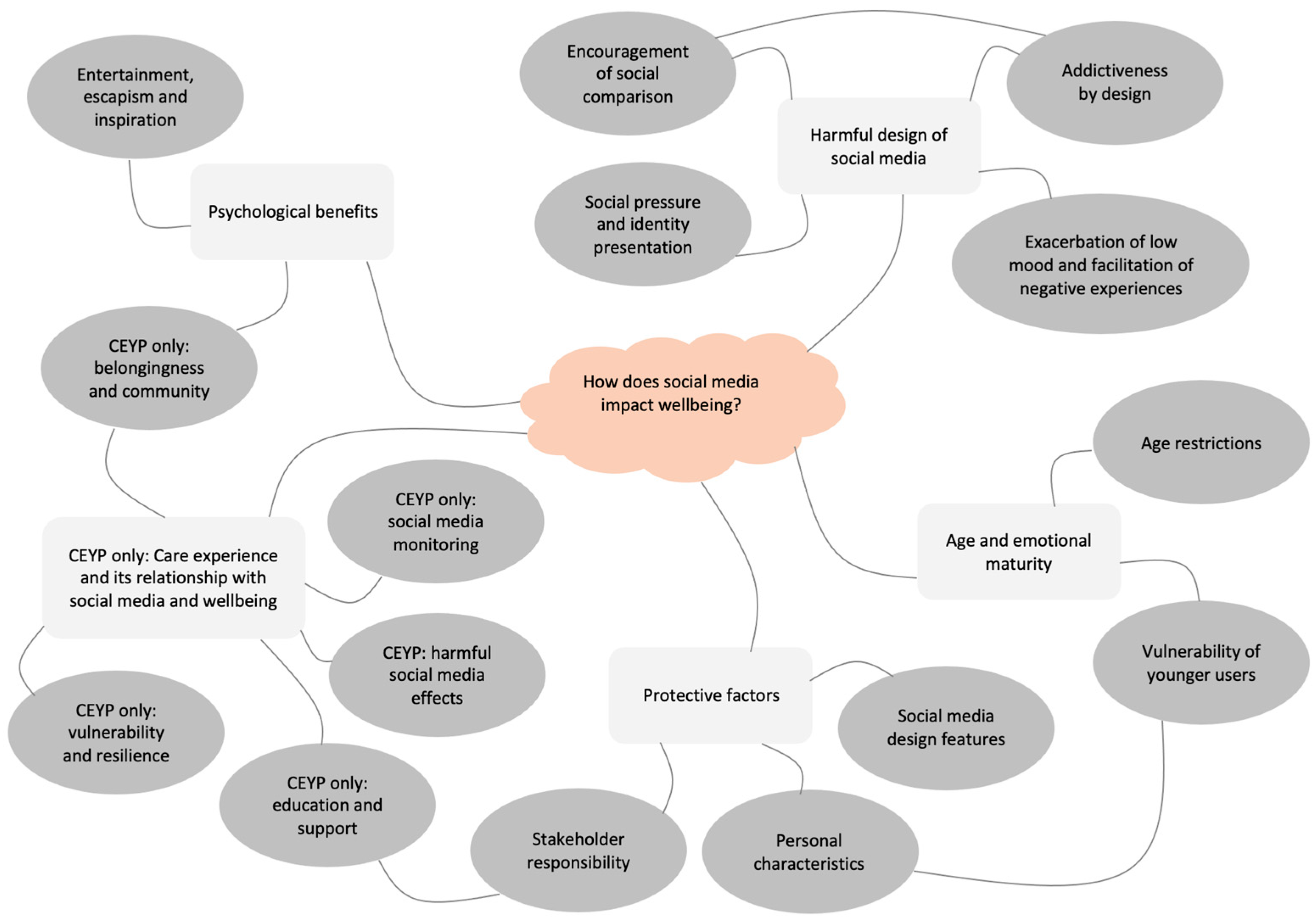

For ease of viewing and to see a visual representation of how the concepts are related, the findings are also displayed in a conceptual map in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

A conceptual map of the findings, with connecting lines showing how the concepts link (abbreviation CEYP stands for care-experienced young people).

3.1. Theme 1: Psychological Benefits of SM

All 22 participants agreed that SM can have positive effects on wellbeing in various ways, including the provision of entertainment and inspiration. SM was described as funny and uplifting and was used to communicate and joke with friends, all of which had a positive impact on mood. Positive, downward comparisons (social comparisons against others who are perceived as inferior [42]) also occurred, which resulted in either motivation or inspiration. Some participants mentioned using SM as an escape from their mundane or stressful lives to improve their mood. Others discussed the benefit of receiving supportive and complimentary comments from friends and family on SM, particularly on photos of themselves or posts about their achievements, which would boost their self-esteem. This was illustrated by participant O, who described the confidence boost felt when receiving praise from peers on SM:

“Me and my friends… we all kind of like comment on each other’s posts like, oh “well done” if someone’s achieved something. It gives you that confidence boost.”—Participant O (general population).

Group-Specific Subtheme 1a: Belongingness and Community for Care-Experienced Young People

This subtheme, specific to the care-experienced group only, highlighted the importance of gaining a sense of community, belongingness, and identity from SM. A total of 9 out of 11 care-experienced participants reported psychological benefits from using SM platforms—primarily Twitter and Reddit—to connect, make friends, and give and gain support from others who had also experienced the care system. Seeing relatable content from others who were care-experienced and seeing similar, validating experiences had a significant positive effect on participants’ wellbeing. This enabled the young people to feel like they had somewhere to belong, as well as having a support network of other people who had been through similar life experiences. Using SM platforms for activism and to advocate for care-experienced people’s rights was also positive for participants’ mental health, as the young people felt it gave them a purpose and motivation. Participant AB described how they felt about the care-experienced community on Twitter and the influence this had on their wellbeing:

“I’ve found Twitter to be really good for my self-esteem… With the care experience community, it’s really helped me find a community I can relate to. I like seeing people who I have that in common with and being able to see them do well… Just joining Twitter and being part of the care-experienced community has had a hugely positive effect on me, it’s like empowered me… it’s so nice to have that community and sense of belongingness. Like peer support and representation, it’s so empowering.”—Participant AB (care-experienced).

3.2. Theme 2: The Harmful Design of SM

3.2.1. Subtheme 2a: Encouragement of Social Comparison

Around 82% of young people from both participant groups felt that the design of SM was harmful because it generally encouraged the users to compare themselves negatively against others through likes, comments, and other quantifiable feedback. Additionally, the participants felt that SM presented only the most favourable parts of a person’s life, which naturally made them feel as though they were not good enough or missing out on a more exciting life. This resulted in feelings of ‘FoMO’, which had negative implications for mental wellbeing, illustrated by participant AC:

“Yeah… Instagram, for example. Twitter as well. You can always see what your friends are up to or people you’re not so close with, you see that they’re doing, like going on holidays or going to fancy places. Sometimes you just compare yourself and go ‘I wish I was out, and I wish I was doing that really cool thing’. Yeah, because the self-esteem issue just kind of [makes you] wonder if you’re, let’s say, as high up in the social ranking as they are.”—Participant AC (care-experienced).

The idea that what is presented on SM is considered fake was expressed by participants, especially with the rising use of filters that change your facial structure and appearance. Some participants felt that filters were toxic and extremely damaging to self-esteem and wellbeing due to adding to the existing, toxic beauty standards that exist online, which young people compare themselves negatively against. Therefore, along with the already high beauty standards on SM to compare to, SM presents a world that is unrealistic and standards that are unattainable due to the ability to alter one’s appearance without others knowing.

3.2.2. Subtheme 2b: Social Pressure and Identity Presentation

The second subtheme showed that young people feel pressure from SM to fit in and seek approval through likes and feedback. The young people reported feeling pressure to use filters like others to live up to the beauty standards online, which resulted in lowered self-esteem and self-view due to not feeling good enough without a filter enhancing one’s appearance. For the care-experienced group especially, identity was discussed in detail and how this societal pressure via SM impacts upon identity formation. Approval was seen as important on SM for care-experienced people, so they were not seen as outcasts. This was a concern for some young people because they already felt different due to their care experience, so fitting in on SM was important for them. Likewise, multiple care-experienced participants mentioned the struggle they experience with identity and that SM does not help this struggle, but rather makes it more complex. This was mainly due to SM rapidly changing, with the trends and fashionable content ever evolving, which made identity formation complicated and subject to repeated and never-ending change. This was demonstrated by participant AA, who expressed their struggle with identity and the pressure they felt to fit in:

“I just never know who I am because I think now, especially with the internet. Like everything is so accessible and there’s just so many different trends and different ways of being a person… I do think it’s hard, because… I’ve never really felt like I’ve fitted in. I do feel like maybe there’s something in that… I feel like I have to fit in some way, and I need to find my group of people.”—Participant AA (care-experienced).

3.2.3. Subtheme 2c: SM Is Addictive by Design

Participants from both groups agreed that SM was designed to be addictive for all users, but especially young people due to the peer pressure they face to fit in, linking to Subtheme 2b above. Participants noted that SM provides a constant stream of content and makes it easy to continue scrolling endlessly, as well as pushing adverts and content that are tailored to your interests, thus facilitating excessive and continuous use. Mixed with the FoMO felt by participants (as seen in Subtheme 2a), this resulted in addictive behaviour for many of the participants. This had a negative impact on wellbeing overall, making participants feel unproductive in other areas of their life and like they lacked control over their SM use. This can be seen below in a quote from participant AI, who felt the persuasive design of SM makes it difficult for young people to disconnect from the online world:

“The way TikTok is built is, it makes you addicted to it because it’s all these really short videos. Obviously, it’s made that way on purpose, but it can be very addicting and I can imagine it being even harder for a teenager to disconnect from TikTok after scrolling for an hour.”—Participant AI (care-experienced).

3.2.4. Subtheme 2d: Exacerbation of Poor Wellbeing or Bad Mood and Facilitation of Negative Experiences

When asked if SM was ever used for self-care, approximately 60% of participants expressed that SM use did the opposite and instead made them feel worse if they were already in a bad mood or were struggling with their wellbeing. This was primarily because of the negative effects SM had on mental wellbeing stated within this theme, such as negative comparison against beauty standards, which, if felt during an existing low mood, would only exacerbate the negative feelings, as participant AF demonstrates:

“I don’t know if I necessarily would go to it [social media] if I was feeling down… I would be more inclined to feel badly if I was going on my social media, if I was already in a bad mood.”.—Participant AF (general population).

Participants also highlighted (the care-experienced group more so) that SM facilitated and provided a platform for other negative behaviour, namely general negativity or trolling, cyberbullying, and ignorance about social class or people from disadvantaged backgrounds. The young people felt that SM contributed to negativity in society by allowing users to post harmful and disrespectful content. Some care-experienced participants mentioned feeling stigmatised after reading content regarding care experience (as seen from participant AC below), or anger from reading ignorant and insensitive SM posts about marginalised groups such as care-experienced people.

“I know there’s been times where I felt stigmatized when I read things about care experience that’ve really got to me.”—Participant AC (care-experienced).

3.3. Theme 3: Age and Emotional Maturity

3.3.1. Subtheme 3a: Vulnerability of Younger Users

It was highlighted by 17 out of 22 participants that the younger generation are now growing up with SM and perhaps face more pressure to use it more often, leading to conversations around the importance of age. The older participants, aged 18 and above, reflected on their SM use during adolescence and conveyed that they felt much more vulnerable when they were younger towards the psychological effects of SM. This included feeling more pressure to fit in, negatively comparing themselves more to other peers, feeling a stronger need to receive likes and approval due to peer pressure at school, and having a stronger influence on identity. Some participants compared this to what they see now in younger siblings or friends, who appear much more impressionable and vulnerable on SM during their young age.

The older participants expressed concern over the rising use of SM among very young users, as they only realised the detrimental effects of SM after they became older and more self-aware. Therefore, being older was found to be a protective factor against the negative effects of SM as self-awareness, reflection on usage, and confidence increase with age (more on this is discussed in Theme 4). Some participants also found that their sense of identity became more stable as they grew older, which resulted in feeling less pressure to change themselves or how they present themselves online.

3.3.2. Subtheme 3b: Age Restrictions

Despite the young people in this research having little to no knowledge of SM policies or rules except age limits and general data protection regulation (GDPR), once the Age-Appropriate Design Code [43] was explained by the researcher and discussed with the young people, participants agreed that SM was not abiding by these rules because it was so easy to see inappropriate and harmful content as a young person. It was also highlighted by participants that SM need to do better at both enforcing policies and removing harmful content.

In addition, participants felt strongly that age limits on SM need to be reassessed and better enforced, as participant J illustrates here:

“I think for some social media platforms that [age limits] should be enforced better because you wouldn’t want a 12-year-old on there because there’s some weird stuff on there. That’s the same for Instagram as well because that might affect their mental health… It should be like 14 in my opinion because we get more mature around that age.”—Participant J (care-experienced).

It was agreed among all participants that age limits are important in protecting young people online, although despite their importance they are easily avoided by young people. The participants explained that it is easy to enter a different date of birth when creating a SM account, rendering age limits useless. Despite many of the young people admitting they have entered incorrect dates of birth in SM platforms before, they went on to discuss the importance of age limits due to the damaging and subconscious impact of SM on young people’s mental wellbeing. Regarding the re-assessment and enforcement of age limits on SM, some participants felt age verification or parental approval could be used to improve the safety of young people. However, others felt this was controlling and not the correct way to resolve the issue. Others felt that emotional maturity was important to consider when re-evaluating age limits, as young people mature emotionally at different rates. Thus, an umbrella age limit would not suffice because it does not consider individual developmental and emotional maturity.

3.4. Theme 4: Protective Factors

3.4.1. Subtheme 4a: Personal Characteristics

A total of 18 participants across both groups reported that having the ability to self-regulate emotions helped protect them from negative mental health effects when using SM regularly. This included acts that primarily involved self-monitoring, such as actively deleting content or apps (as participant AA expresses below), deactivating accounts, or avoiding certain content on SM. Interestingly, some care-experienced participants reflected on their difficulty to self-regulate due to their past trauma, which, in turn, exacerbated the negative impact of SM. Other personal characteristics also helped to protect mental wellbeing, with the young people highlighting that high levels of confidence, self-awareness, self-esteem, and self-worth all act as protective factors. This was mainly because these young people only felt the effects of SM on a surface-level and, due to their strong self-concept, did not feel their mental health was impacted negatively by what they saw on SM. General awareness that SM was not an accurate portrayal of life was also highlighted as a protective feature.

“I used to use TikTok… but I had to delete it because it was just addictive […] I’ve not been very well… all I could do is lay in bed. I was just scrolling through social media and I just- it was making me so depressed because I just saw everyone going out and doing things… But it was like everyone was just living their life and I was stuck at home. And that’s when I ended up deleting TikTok, because I was just so miserable about it in the end.”—Participant AA (care-experienced).

3.4.2. Subtheme 4b: SM Design Features

This subtheme was highly significant in terms of prevalence, with 91% of participants discussing the role of SM designers in protecting young people from online harm. Participants highlighted the current design features that act as protective factors as well as potential design features that would aid this further. These included the ability to privatise your account to protect oneself from negativity or mentally triggering content, being able to block or report to remove harmful content, hiding likes to reduce the pressure to self-compare, the encouragement of honest and transparent content, and being able to tailor content to one’s interests. All these features protected the participants from the negative effects on mental wellbeing by increasing feelings of safety and reducing the natural tendency to negatively compare oneself to other people’s successes.

Whereas participants were glad these protective design features exist, the young people also mentioned that the design of SM could be improved further to protect them from harm. These suggestions included using better technology to improve the speed of detecting and removing harmful content, encouraging more age-appropriate content, using trigger warnings on all sensitive content, and taking action to reduce the addictive design of SM. This is illustrated by participant AB below, who felt that SM companies are irresponsible by not providing these design features that could protect young people from harm. Participants felt that if SM designers incorporated these suggestions, then SM would be much less likely to have a negative psychological effect on young users due to increasing the chances of protection from possible harm.

“And all the like glamorization of self-harm… I mean I get why young people do it, it’s a coping mechanism, but it’s social media’s responsibility to take that stuff down. They should be better at detecting this harmful stuff and taking it down faster. You know what’s been really good for me, I find trigger warnings really useful but again that’s not social media policy, that’s the users discretion. I just think social media has a lot to answer for.”—Participant AB (care-experienced).

3.4.3. Subtheme 4c: Stakeholder Responsibility

Participants explained that they had limited knowledge of any mental health policies or guidelines on SM. Therefore, the young people believed they should be educated more about SM, mental health policies, and any potential effects of SM on their mental health to prepare them. A total of 19 participants across both groups felt that if they were educated in these aspects, they would feel more protected and less likely to suffer any negative emotional effects. This education was felt to be the responsibility of educators, such as the government and schools. It was highlighted that current school curricula focused on teaching young people how to use SM for employment benefits, how to be cautious about what to post due to future employment, and the importance of privacy settings. Whereas participants acknowledged the importance of these aspects, they also believed that education and awareness about the potential psychological effects of SM is a crucial step in teaching young people how to use SM safely and to manage their emotional wellbeing, as demonstrated by participant O:

“I think it should be made more aware like in school, they should have that message put across saying “look, it doesn’t matter… you can’t make someone like your post.”—Participant O (general population).

As well as education, participants felt that SM companies and the government need to improve current policies to keep young people safe because they are currently failing. Participants felt that little is being done to protect young people online and that SM companies and the government need to take accountability and more responsibility for young people’s mental health, through both education and improving SM platforms. Furthermore, it was highlighted that more funding and resources are needed for young people’s mental health; however, SM companies are profit-focused and unwilling to spend money on design improvements that could help young people’s mental health. Therefore, SM companies need to reflect on their priorities and focus more on protecting the mental health of young generations. This subtheme is represented well by this quote from participant AD:

“I sometimes feel as though they [social media policies] are not fit for practice really. Social media companies should be held more accountable too… for example, Snapchat, Instagram, they give you the filters to put on, you’re given that, they provide them. So, it’s not like you’re having to go to another app to get that filter and then upload it to your snap. You can just do it on the actual platform. I think it’s wrong. Yeah, they shouldn’t be allowing that to happen.”—Participant AD (care-experienced).

3.5. Group-Specific Theme 5: Care Experience, SM Use, and Mental Wellbeing

3.5.1. Group-Specific Subtheme 5a: Vulnerability and Resilience

This first subtheme consisted of 10 out of 11 participants explaining that vulnerability starts at an elevated level in care experience due to the trauma and difficult life situations they have been through. However, this vulnerability made the young people feel more resilient to life challenges over time. Some participants believed that their increased resilience was due to time, experience, and age, whereas others felt it was due to the care experience specifically. For example, having to move around frequently in care made the young people feel more resilient and more capable of surviving change and challenges. Experience of the care system also resulted in validation for some participants, regarding their experiences with birth families and other trauma. One participant reported that their stable care experience in foster care, of which they admitted the stability was rare, allowed them to feel safe enough to find and establish their identity, which was beneficial for their resilience and mental wellbeing.

3.5.2. Group-Specific Subtheme 5b: SM Monitoring

The second subtheme reflects on how care experience differs to the general, non-care-experienced childhood experience, drawing on the effect of the young people’s SM use being strictly monitored or completely restricted throughout their childhood by carers or social care staff. Approximately 64% of participants reflected on the advantages and disadvantages of this experience. Advantages included feeling safer and less at risk from dangerous behaviour, feeling protected from the negative effects SM can have on mental wellbeing, and feeling less obsessed with the need to be on SM all the time. Care-experienced young people who had strictly monitored SM use now believed they were less fixated on approval from likes and other SM features, which was beneficial to their mental wellbeing. On the other hand, participants reflected on the disadvantages of having a strictly monitored childhood. The primary disadvantage was the frustration caused by the exacerbation of feeling different and missing out on a regular childhood. Participants conveyed that it was already difficult to lead a ‘normal’ childhood while in care, so the strict monitoring of SM and mobile phone use made it even harder to fit in with other children. Whereas participants showed awareness of the importance of monitoring care-experienced young people’s SM for safety reasons, they were frustrated that this was necessary in the first place because it made them feel like an outcast.

3.5.3. Group-Specific Subtheme 5c: Beneficial SM Effects for Care-Experienced Young People

Comparably to Subtheme 1a, the feeling of belongingness, community, and support gained from SM use had a significantly positive impact on mental health and wellbeing. Being able to find similar communities and relate to other people had a positive impact on the self-esteem, identity, and general wellbeing of care-experienced young people. It was also highlighted by participants that care experience results in moving around regularly and thus it is important to maintain contact with foster carers, siblings, or other people they formed a close bond with. SM can therefore be useful when wanting to maintain contact with these individuals.

The care-experienced participants also gained validation from SM by connecting with other care-experienced people online, which has helped to validate some participants’ experiences of care and trauma. The importance of private accounts for safety reasons was also discussed by participants, with some reflecting that this SM feature is more important for people who have suffered trauma or have a complicated family background, so they can remain safe. Moreover, some participants use SM to advocate for and raise awareness of care experience and as a source of information about care experience. The ability to do this has had a positive impact on mental health and identity and has been an outlet for some of the participants to share their care experience with the hope of helping others. Participant AB described how impactful the care-experienced community has been for their wellbeing, often serving as a coping mechanism to avoid relapses of depression:

“I think for me, the use of social media for activism and advocacy has been massively impactful on my mental health […] When you’re in the care system, I felt completely fed up with the world. I thought everybody in the world was evil and like I’m just gonna be traumatised for the rest of my life […] I guess being empowered by other care-experienced people online, seeing what they’re doing to help others in the community, empowered me to get into activism and advocacy. And that is genuinely, I’ve got to say, it’s probably one of the biggest drivers in getting my mental health to stay stable for the first time ever. And the reason is, is it gives me that control back and that ability to go actually “that’s not OK” and kind of fight for something and it gives you purpose to get up in the morning. And, you know, times where I do feel like I’m slipping back into the depression, I feel like I can’t, almost, because I have somebody to fight for now that doesn’t have a voice. That’s been hugely impactful on my mental health.”—Participant AB (care-experienced).

3.5.4. Group-Specific Subtheme 5d: Harmful SM Effects for Care-Experienced Young People

This subtheme was substantial in size when considering the number of codes generated, with contributions from 7 out of 11 participants. Participants mentioned that being in care had made them more vulnerable, especially when younger, which, in turn, made them more vulnerable to the generic negative effects of SM. Some participants acknowledged that care-experienced people are highly susceptible to developing mental health issues or may already have mental health concerns themselves, so the increased vulnerability mixed with the societal pressure to use SM regularly is worrying when considering how SM can have a subconscious, negative impact on mental wellbeing.

It was also argued that avoiding mental health triggers in real life was mostly achievable, whereas this was difficult on SM due to the lack of control around what kind of content is viewed. Again, similarly to Subtheme 4a, older participants reflected on their own struggle to self-regulate their emotions due to their trauma, which they also saw in other care-experienced young people online. This made the young people feel more vulnerable online and feel that the risk of revealing too much or getting into dangerous situations was higher than that of the average population. Moreover, some participants felt more vulnerable because they lacked parental reassurance, support, and comfort from loved ones during childhood when on SM and facing challenges.

The care-experienced young people conveyed that they feel different due to having different family lives compared to their peers, which was heightened when comparing oneself to others online. Participants had already experienced many life obstacles and felt that, when compared to other young people online, their life was not worthy to share. The feeling of FoMO was thought to be more severe for care-experienced young people due to having to grow up quickly in care, as well as not having a regular or common upbringing and everything that comes with that adversity. Participants additionally revealed that SM expectations are even more unrealistic for care-experienced people due to obstacles they face, such as a lack of financial stability, a lack of familial support, and general limiting personal circumstances. Participant AJ specifically described how going to university was thought to be unattainable due to being a care leaver and the obstacles they face:

“I had this goal in my head for so many years that I would get to university and that was my goal. But it was so unattainable for a care leaver, I don’t know a single care leaver who’s gone to university… I know probably two or three girls out the whole of the UK.”—Participant AJ (care-experienced).

The final care-specific negative effect revolved around the pressure to find or create a stable identity. Being in care often resulted in an insecure identity and a lack of belongingness for some participants, which was worsened when comparing to other people’s ‘perfect’ lives on SM, so it was generalised by participants that this population feel more pressure to find an identity. Whereas this could have a positive effect if the young person found care communities to relate to on SM, it could also have a negative effect if an identity or community was not found. For example, one participant reflected on their unhealthy reliance on SM to find a purpose and sense of belonging in life because they do not receive that from family (see the illustrative quote used for Theme 5 in Table 2).

3.5.5. Group-Specific Subtheme 5e: Education and Support

This subtheme was primarily formed from ideas from older participants, with their age and experience being a key factor in their reflection on this topic. These participants reflected on their damaging SM use, including seeking out damaging content on SM for attention both before and during their care experience and wishing they had received more support from social care services. In addition to more support, participants felt that care-experienced young people should be taught to develop their emotional life skills as well as being taught how to use SM safely, so they are more prepared to deal with the psychological challenges that come with regular SM use. An example of these emotional life skills would be working on emotion and self-regulation, so they can learn how to effectively deal with the flood of emotions that come with using SM during adolescence.

It was pointed out by participants that the use of SM is increasing, so social care services need to stay up-to-date, work with this—and not deny or completely restrict it—and help young people prepare for this, especially for when they leave care and must deal with the consequences alone (as expressed by participant AH below). Participants believed this education and support around SM and mental wellbeing would ideally be balanced between keeping the young people safe while still granting them opportunities and trusting them to explore their interests. Likewise, any communication surrounding this education and support should be open, enable trust, and yet set boundaries to maximise comfort for everybody involved.

“We can’t run from social media and I think that everyone’s just put their heads in the sand […] You know, we need to consider contact, we need to consider support for birth family, better ways they can reach out later in the child’s life. […] I think the care system needs to catch up with social media, it’s getting more complex every day. It’s becoming more of an integral part of people’s day-to-day life, especially after lockdown. And actually, we’re not going to be able to stop it. It’s like a tsunami coming… you’re either going to learn how to work with it or you’re going to run.”—Participant AH (care-experienced).

4. Discussion

This detailed study offers a range of findings that contribute to our understanding of how SM impacts upon the mental wellbeing of young people from the general population and care-experienced young people. As well as this insight and development of knowledge, the widespread findings contribute to the existing literature in the multidisciplinary fields of psychology, sociology, and computer science and communication while also providing novel contributions from an underrepresented population (care-experienced young people). This discussion will explore the themes found from the reflexive thematic analysis and implications for real-world improvements to mental wellbeing.

4.1. Psychological Benefits of SM

The first theme found conveyed multiple emotional benefits of regular SM use, which were consistent with previous research [24,25] and provides one potential answer to RQ1. The care-experienced young people involved in the research expressed the importance of using SM for belongingness and to find relatable care-experienced communities, which expresses the importance of providing a social platform for young people from a minority group, such as those who have lived experience of the care system. These findings are consistent with existing literature that demonstrates how care-experienced young people can have trouble feeling a sense of belonging due to their past trauma and non-traditional family background [44]. This research also supports broader research that suggests young people who have low self-esteem may think of SM as a safe place to maintain friendships, which allows them to gain support and attention from others [20].

4.2. The Harmful Design and Consequences of SM

The second theme produced from this research conveys the numerous ways in which SM platforms can have a damaging impact on the self-view and wellbeing of young people, again providing more answers to RQ1. These primarily consisted of discussing the harmful impact of SM design (addictive in nature, with design features that encourage negative, upwards social comparison to others and subsequently result in reduced wellbeing and self-view). As well as these design features, SM in general also created prominent levels of social pressure to fit in with others and seek approval, especially in the form of SM likes. These findings are consistent with past literature, including research that has found SM design to be persuasive and thus often results in FoMO [12,14], that peer pressure is a key driving force in online behaviour [45], and that SM use can often result in upwards social comparisons and self-criticism [46].

These findings are also consistent when considering the developmental period of adolescence, as during this period there is a heightened salience of social norms, and more importance is placed on peer feedback [33]. Care-experienced young people primarily felt pressure in a unique way compared to the other group, as they felt pressure to ‘find’ an identity when on SM. This is consistent with psychological theories regarding identity. For example, Erikson’s [36] stages of psychosocial development suggest that identity is formed through life stage ‘crises’ in which identity clashes with confusion, and successful transitions are required to form a stable identity. So, a key period of instability occurs before adolescents form their identity, which causes vulnerability due to constant psychological and physiological changes [47]. As a result of this, any threats or stressors during this period of development can have worsened effects on identity [48]. Therefore, as care-experienced young people are likely to have experienced stressors, neglect, or trauma during their childhood, they are likely to struggle with an unstable identity [44].

The final subtheme in Theme 2 describes how SM can exacerbate poor mental health or low mood while also facilitating negative behaviour, such as cyberbullying. This was most relevant to the young people who were prone to low mood or for those who have existing mental health issues, as SM added to those existing feelings and exacerbated them by presenting a ‘perfect’ façade and encouraging negative, upward social comparison (as also suggested by Reinecke and Trepte [18]). The care-experienced participants agreed with this but additionally discussed the extra barriers care-experienced young people face due to their lived experiences of trauma and having such different lived experiences and opportunities compared to the average young person. Therefore, this supports the literature that shows care-experienced young people are more susceptible to developing mental health issues [3,49,50], which can be heightened further due to SM use.

Nevertheless, this finding also conveys that young people who may be prone to low mood or mental health issues can find that SM exacerbates this feeling and thus could be harmful for mental wellbeing. These concerns align with recent suggestions from Choukas-Bradley et al. [34], who proposed that the design features of SM (namely the ‘perfect’ and idealised content and the quantifiable and comparable feedback such as likes) significantly overlap with the social and developmental processes occurring in adolescence, such as the salience of peer feedback, social pressure, and heightened self-consciousness. Along with additional gender pressures for girls to look an ideal way, these conditions create the “perfect storm” for exacerbating body image concerns, which may extend to further mental wellbeing issues for some young people [34]. Thus, this finding and the consistent previous literature suggest that SM design may be harmful particularly for young females, as well as for those who may be prone to negative social comparison styles or mental health issues. Unfortunately, only a slight gender difference was apparent in this analysis which was not significant enough to warrant a separate theme. Therefore, while this study provides some support for this, more exploratory research focussing on gender is needed.

4.3. Age and Development

The third theme conveys that age and development are highly significant when considering the impact of SM on mental wellness. Older participants in this research (aged 16 plus) reflected that when they were younger, they did not realise the harmful impact that SM was having on their sense of self and general mental wellbeing. To support this further, the younger participants (15 years and under) reported predominantly positive effects of SM. It is impossible to say whether this is because they were simply not impacted negatively by SM, or whether any negative impacts were subconsciously occurring and would only be realised later as suggested by the older participants. If the younger participants did mention negative effects of SM, they reported not being significantly affected by them, in that they were able to ‘brush off’ whatever the feeling was (i.e., the impact was fleeting). Although, the older participants reflected on how damaging SM had been for their wellbeing when they were younger, suggesting that this may be a subconscious effect. Therefore, this finding adds to the importance of considering age and development (and subsequent vulnerability) when designing SM and creating policies and guidelines around SM use for young people. Moreover, it suggests the need for improved education and awareness of the potential emotional impact of SM on young people.

The second subtheme within the third theme was centred around age limits and restrictions. Participants felt that age limits were easily evaded, should be increased, and did not consider the importance of emotional maturity. Thus, this suggests that age limits on SM need to be reassessed. Despite this, the participants discussed how they had easily managed to evade age restrictions themselves to either join SM platforms when below the age limit or to view adult-restricted material. This suggests that participants may not honestly have believed that age limits can keep young people safe and that perhaps the design and protective measures on SM sites need to be reassessed considering the significance of age, emotional maturity, and developmental stages, rather than simply enforcing stricter age restrictions. Likewise, the participants had not heard of the Age-Appropriate Design Code, but once this was explained to them, they agreed that SM platforms are not adhering to these rules; hence, it needs to be enforced more effectively. This finding also shows that more education on existing policies to keep young people safe is needed to raise awareness among young people and how to protect mental wellness online.

4.4. Protective Factors

The first two subthemes within this theme describe two key protective factors that helped to safeguard young people from the damaging effects of SM. These factors were split into two categories: protective factors that were personal in nature and protective factors that stemmed from the design of SM platforms. Personal characteristics included self-awareness, confidence, high self-esteem, and self-reflection. In other words, having a strong self-concept seemed to protect the young people from taking part in behaviours or thinking styles that would contribute negatively to their emotional wellbeing. SM design features, such as hiding likes and private accounts, were also key in protecting young people’s mental health online, as other research has similarly found [26], and hence should be strongly considered by researchers, SM companies, and other stakeholders like policymakers and educators.

In addition, this study found that young people felt that the role of protecting their mental health online fell into the hands of others as well as themselves, although this view of responsibility differed fractionally between participant groups. The non-care-experienced young people focussed more on the role of schools and other educators to protect their mental wellbeing online, suggesting the need for more education and awareness in school curricula around the relationship between SM and mental wellbeing. Alternatively, care-experienced young people focussed more on the responsibility of social care and policymakers, understandably due to their experience with social workers and, perhaps, the law and advocacy. Another potential reason for the focus on policymakers was due to care-experienced young people having an externally controlled upbringing, often led by social care professionals (SCPs) and governed by strict rules and guidelines. Consequently, while the focus varies for the two groups slightly, this finding conveys that there is an important responsibility from everyone involved in a child’s safety to protect them from online harm. This finding supports recent internet safety laws which recognise the responsibility of SM companies and other stakeholders to keep young people safe online, such as the Age-Appropriate Design Code and the Online Safety Bill, which will make SM companies legally responsible for preventing online harm [43,51].

4.5. Care Experience, SM Use, and Mental Wellbeing

This final theme draws on the data gathered from the care-experienced group only and describes how young people feel care experience directly affects both SM use and mental wellbeing, and how these two factors are linked. The first subtheme provided insight into how care-experienced young people feel more vulnerable, especially when younger and in the initial stages of being in care. This is consistent with the literature and psychological theories that suggest care-experienced young people are more vulnerable due to trauma and deprivation [52,53]. However, the participants expressed that they had developed into more resilient individuals with time and experience due to their lived experiences of the care system. This can be linked to the literature on ACEs (adverse childhood experiences), in that these events can make a young person more resilient through the development of healthy social relationships and experiences after surviving their individual trauma [54]. Thus, this provides an answer for RQ2 of this study. Likewise, another finding further conveyed that some participants found that being in care had validated their lived experiences of trauma, which had helped them with their mental recovery. This is a useful finding for the future of children’s social care, suggesting that trauma-informed practice and the acknowledgement and validation of a young person’s trauma can be beneficial to wellbeing.

The second subtheme in Theme 5 conveys how differently care-experienced young people’s SM is monitored during their childhood compared to non-care-experienced young people. As many care-experienced young people are not brought up in a traditional family unit, their experiences with the online world and typical parental monitoring differ significantly. This research found that care-experienced young people felt the strict SM monitoring from social workers had both advantages and disadvantages, concluding that a balanced approach is optimal. Therefore, this implies that professionals need to acknowledge the effect strict SM monitoring is having on care-experienced young people and work towards a more balanced approach to enhance and protect mental wellness. For example, this approach could maintain the aspect of safety and boundaries, while working to minimise the monitoring strategies that make care-experienced young people feel like an outcast. This finding is consistent with a report by Anderson and Swanton [55] of the Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership, in which these issues are also identified, and similar next steps are suggested.

The third and fourth subthemes within this theme outlined the care-specific positive and negative effects of SM on mental wellbeing. Primarily, the positives were the importance of SM for community, connection, and belongingness (as also expressed in Theme 1) and SM communities providing validation of lived experiences and mental wellbeing issues. This is again consistent with work by Stein [28] who found that care-experienced young people feel isolated once they leave care and thus turn to SM for support and community, as well as findings that have shown that SM has been beneficial for social interaction, support, and belongingness [27,29]. Therefore, this finding provides further support for the mental and emotional benefits of using SM for social connectedness, especially for those who struggle with identity.

Regarding negative effects on mental wellbeing, the care-experienced group highlighted again what has previously been included in other themes, namely that care-experienced young people are more vulnerable compared to others due to their lived experiences of trauma and neglect, they are more sensitive to FoMO and negative comparison, and they feel more pressure to find an identity because they are largely unsure of who they are during this developmental stage. All these factors align with the literature on care-experienced people stated previously and provide further support for the argument that care-experienced young people have notably unique needs, as their lived experiences can intensify the impact of SM on mental wellbeing. Therefore, SM platforms and policies need to listen and adapt to these needs going forward to protect care-experienced young people’s mental wellbeing.

The final subtheme in Theme 5 is a desire expressed by the care-experienced young people in this research: that they believe more education and support is needed for care-experienced young people to increase awareness of potential mental wellness effects from SM use. Not only is more education and support needed for these young people, but this needs to be carefully balanced between maintaining safety while not limiting opportunities. This is coherent with mediation suggestions from Livingstone et al. [56], who suggested more digital literacy training for parents, carers, and young people themselves to maximise online inclusion and opportunity, while increasing awareness of online risk. Thus, this study conveys that the views, needs, and desires of young people who are often underrepresented in research aligns with suggestions from leading academics too, showing that the opinions and voices of young people are important in research and should be considered by all stakeholders involved in keeping young people safe online.

4.6. Group Differences

The differences between the two participant groups are subtle. Most underlying concepts are similar for both groups, but the differences lie in the level of impact. For the care-experienced young people in this study, their lived experience of trauma and barriers that come with non-traditional upbringings exacerbate the impact SM can have on mental wellbeing. This has been demonstrated through both positive and negative aspects of SM. Therefore, it can be recommended that care-experienced young people have differing psychological needs that need to be met and adapted to by SM companies, the government, and SCPs, that are not yet being fulfilled due to the damaging effects discussed in this research. However, it is important to note that damaging psychological effects also occurred for young people from the general population, thus suggesting that SM companies and other stakeholders need to improve SM platforms for all young users if they wish to prioritise and protect youth mental health.

4.7. Implications, Recommendations, and Limitations

This research has several important implications for the future of SM design and policy. The first theme suggests that SM stakeholders need to acknowledge and prioritise the beneficial features of SM, such as those that encourage entertainment and inspiration. Equally, SM companies should acknowledge the benefits of platforms that enable underrepresented groups, such as care-experienced young people, to form communities for support and guidance, which this study has shown to be significantly beneficial for mental wellbeing. SM companies should also work to enhance the design features that protect young people’s mental health, such as hiding likes, the accurate tailoring of content, and good privacy settings (see Theme 4).

Secondly, SM companies have a responsibility to reflect and act upon how their platforms are impacting upon young people’s mental health and implement appropriate changes. It is apparent from this research that SM can have a damaging impact on self-view and general wellbeing. From the harmful consequences found, it can be concluded that SM designers should be held accountable and make a firm commitment to improve current algorithmic and design practices to prevent the encouragement of unattainable and biased beauty standards (particularly regarding filters and editing) and readdress the persuasive design of SM to reduce the addictive behaviour many young people are experiencing and the subsequent negative impact on wellbeing. Moreover, this study has conveyed the differing needs of care-experienced young people and young people who may be more prone to negative social comparison. Thus, this implies that these young people may need additional support both online and offline to lessen the negative impact SM may have on their wellbeing.

The third theme found in this study conveys the importance of age and individual development of young people when considering how SM affects mental wellbeing. Therefore, from this finding, it can be recommended that the implementation of the Age-Appropriate Design Code needs to be more seriously enforced and adhered to by SM platforms. In addition to this, SM designers should take these considerations into account and focus on providing more age-appropriate content. For example, rather than using age restrictions that are easily evaded by young people, they could incorporate content-filtering and other measures to protect younger users from seeing harmful content.

Similarly, from the information gained from Theme 3, it could be suggested that the realisation of SM having a negative impact on the sense of self during formative and important developmental years only occurs during older adolescence, once the ‘damage’ has already been done. Therefore, this implies that more education on the potential impact SM could have on wellbeing is needed during younger years of childhood and in early adolescence to raise self-awareness. This way, the young person can gain autonomy and may be able to recognise the impact of SM before it has damaged their sense of self and increased susceptibility to the development of mental health issues. This is also consistent with suggestions from Theme 4, in which having higher self-awareness can protect younger users from harmful impact. So, the encouragement of education and learning how to accept oneself and develop confidence is important for young people.

The final insight gained from this study is the glance into care-experienced young people’s lived experiences of care and how this can affect mental wellbeing and SM use. The findings convey the differing needs of care-experienced young people both in their general wellbeing, their wellbeing on SM platforms, and the way SM use should be monitored throughout childhood by SCPs. This study has shown that the effects the average young person feels from SM are amplified for care-experienced young people due to the lived experiences they have had and the extra barriers they face. As a result of this, both SM designers and policymakers need to consider this impact and work to create an online space that is safe and mentally positive for all users.

One limitation of this study is the small sample size. Whereas the sample size is average for a qualitative study, it can be considered small when reflecting on the transferability of the findings to wider populations. Likewise, there was a bias in the gender of participants, with more females being recruited than males, and some differences in ethnicity, thus limiting transferability and the comparisons made. The recruitment method may also have resulted in a biased sample. As stated, Twitter was used to recruit older participants through the hashtag ‘#CEP’ (care-experienced people). Although this was an effective way to recruit care leavers, many of the young people who used Twitter and the CEP hashtag were advocates for care-experienced people’s rights and were active members of the community. Therefore, it is understandable that a key finding of this research relays the voice of this online community, in that connection and community is an important part of SM use for care-experienced young people. Whereas this may be true and transferable for many others, it can be considered biased due to how the sample was recruited.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study used a semi-structured interview technique to gain detailed information into how SM affects young people, both from the general population and those who are care-experienced. Reflexive thematic analyses were completed for the two groups of participants, which were then compared to explore the differences between groups. The findings conveyed that young people could feel emotional benefits from regular SM use, such as entertainment and escapism. An insightful finding from the care-experienced group was the value of using SM for social connection and community to feel a sense of belongingness, which enhances mental wellbeing. On the other hand, SM design was criticised by the young people in this research for its addictive design and apparent encouragement to compare oneself negatively against others. This conveys the need for the SM industry to better adhere to responsible practices that prioritise user wellbeing and safety and the need for active steps in SM design and policy to reduce exposure to harm [5].

When looking at how young people could be protected from negativity online, several factors emerged. Firstly, age and development were shown to be significant factors in how SM impacts young people, thus suggesting that SM stakeholders need to consider this in design and policy adaptation. Furthermore, participants highlighted design features of SM that were beneficial in protecting youth mental health, which provides implications for SM companies. Along with these, recommendations for more education were provided to improve young people’s self-awareness and digital literacy, as strong self-concept was shown to be another protective factor. Finally, findings around care-experienced young people’s lived experiences of care and the impact this has had on mental wellbeing and SM use provide useful and novel insights that henceforth lead to recommendations for future SM design, policy, and SM monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., E.P.V. and C.J.C.; methodology, C.P.; formal analysis, C.P.; analysis blindly reviewed by, E.P.V.; investigation, C.P.; data curation, C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.; writing—review and editing, C.P., E.P.V. and C.J.C.; supervision, E.P.V. and C.J.C.; project administration, C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Horizon Centre for Doctoral Training at the University of Nottingham and is funded by: the EPSRC, UKRI grant number EP/S023305/1 and by the external partner The Biomedical Research Centre, University of Nottingham; the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health and Digital Technology; and the Haydn Green Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Nottingham reviewed this study as part of author CP’s doctoral thesis and was approved (ethics reference number: FMHS 137-1220).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participant(s) to publish their anonymised quotes in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions, and due to being part of the author CP’s doctoral thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Discussion guide for the interviews.

First, there will be an introduction from the researcher, saying something like this:

“Hello, I am Cecily, and this interview is part of a study I am doing about how social media makes us feel and how it may affect young people’s mental wellbeing. All your answers will be anonymised, so no one will know they come from you, and you can withdraw at any time without any explanation if you ever feel uncomfortable. You can also skip questions if they make you feel uncomfortable too. There are no wrong or right answers, I’m just interested in hearing your opinion and your experiences with using social media.”

There will then be an icebreaker, where the researcher will ask the following questions:

| Questions | |

| 1 | Do you use social media and how much? |

| 2 | What type of social media do you use? |

| 3 | Do you have a favourite and least favourite social media site? |

| 4 | Do you use different social media sites for different purposes? i.e., Instagram for photos, Twitter for news etc. |

After this, the main part of the interview will start, with the following questions:

| Questions [Category] | Probes | |

| 1 | How do you feel social media impacts upon your wellbeing? [Things like self-esteem, mood, wellness, confidence etc.] | Do you feel it has a negative or positive effect? Can ask them what their definition of wellbeing is and how social media use affects this |

| 2 | Do you find yourself comparing yourself to others? Is this in a negative or positive light? | How does this make you feel about your own self-image and worthiness? Do you feel inspired/positive when you compare, or do you feel less worthy/negative? Why do you think this might be? |

| 3 | Do you feel other people’s approval is important when posting things on social media? If so, why do you think this is? | How do you feel when looking at feedback on your posts? How do you feel if you receive a lack of feedback or likes? What level of importance do likes, or other feedback have for you? |

| 4 | How do you feel social media affects your identity and who you are as a person? | Do comments or feedback ever make you feel like you should change your personality or what you wear or how you act? Do you ever adapt your personality to ‘fit in’ with what you see online? If so, why? Do you feel like you have a different personality when you’re online compared to offline/in-person? |

| 5 | Can you tell me a story about a time social media made you feel unworthy or not good enough? | Why do you think it made you feel that way? |

| 6 | Can you tell me a story about a time social media made you feel uplifted or positive about yourself? | Why do you think it made you feel that way? |

| 7 | Do you ever use social media purposefully to help look after and improve your well-being? For example, if you’re feeling low one day, do you use social media to help you feel better? If so, how? | Do you think social media could make this easier in any way? Or have any other features that would make this better? |

| Break (if participant would like one) | ||

| 8 | Do you know any policies and guidelines that are in place to make sure social media isn’t harming young people’s wellbeing? | If they don’t understand what a policy is, explain in simpler terms. |

| [After discussing current guidelines briefly and in simple terms] | ||

| 9 | Do you feel like these are enough to make sure young people don’t let social media make them feel bad about themselves to an extent where it’s damaging their mental health? | If not, do you have any ideas on how you would change them or new ones that you’d like to see? |

For care-experienced participants only (remind participants that they do not have to discuss things that make them upset or uncomfortable, and remind them of their right to withdraw, stop, or take breaks):

- How do you feel your childhood and being in care has affected your social media use?

- Do you think your personal experiences have made you tougher and able to cope better with any negative effects? Or do you feel your experiences have had a more negative effect on how social media makes you feel?

- Why do you think this is?

Finally, the researcher will ask if the participant has anything else they would like to add. Then, participants will be thanked for their time, and asked if they have any further questions. The interview will then end.

References

- Ofcom. Children and Parents: Media Use and Attitudes Report 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/234609/childrens-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Aichner, T.; Grünfelder, M.; Maurer, O.; Jegeni, D. Twenty-Five Years of Social Media: A Review of Social Media Applications and Definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, W.; Jones, J. Addressing the mental health needs of looked after children in foster care: The experiences of foster carers. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, P.; Manktelow, R.; Taylor, B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 41, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. Social Media and Youth Mental Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/sg-youth-mental-health-social-media-advisory.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J.; Schouten, A.P. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesal, M.; Rahimi, C. The influence of social media use on depression in adolescents: A systematic review & meta-analysis. J. Arak Univ. Med. Sci. JAMS 2021, 24, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]