Abstract

This study investigates how perceived parental criticism is associated with career confidence in students and workers, considering the mediating role of the fear of an uncertain future. In a rapidly changing labor market, students, as young individuals navigating early career decisions, experience heightened uncertainty about their future, especially regarding their professional paths. This research aims to verify whether perceived parental criticism negatively affects career confidence both directly and indirectly through the mediating role of fear of an uncertain future, and whether occupational status (being a student or already working) influences this relationship. Data were collected from a sample of 310 participants, consisting of 108 students and 202 workers. Multigroup structural equation models were used to test the mediation model simultaneously on students and workers. The results indicate that, in students, the relationship between parental criticism and career confidence is fully mediated by fear of an uncertain future, while in workers these associations are weaker and not significant. These findings suggest that students are more vulnerable to uncertainty, as they are in an early stage of career development, while workers may benefit from greater independence and emotional regulation skills. The study highlights the impact of perceived parental criticism on career confidence and the moderating role of occupational status, suggesting the need for interventions that reduce the fear of an uncertain future and encourage greater adaptability to career-related challenges.

1. Introduction

The current labor market, characterized by instability and changeability, is subject to rapid change and uncertain prospects (Greenhaus et al., 2008). Therefore, the issue of insecurity is more relevant than ever (Cheng & Chan, 2008). Uncertainty, along with career transitions and traumatic events such as job loss, requires workers to constantly adapt (Savickas, 2013). This implies the need to maintain continuous control over one’s career path and to be confident in one’s ability to cope with career-related challenges (Savickas, 2005; Van der Horst et al., 2017). Variables such as age, experience, and occupational status may have an influence. According to some theories (Carstensen et al., 1999; Charles, 2010), as people age and consequently gain experience, they tend to prioritize emotional and social goals, while younger people focus on goals related to information acquisition and long-term planning. This shift is related to a reduced future time perspective and the fact that career-related goals may have already been achieved for the most part. On the other hand, students, as younger individuals with a longer time horizon and fewer goals achieved, suffer from greater uncertainty due to the difficulty of predicting their future. Uncertainty tends to decrease moving towards more certain and immediate goals and reducing exposure to uncertain situations. Several studies (e.g., Gallup Organization, 2023) report that the so-called Gen Z (people born between 1995 and 2010) view their prospects as largely uncertain and nebulous in relation to their future careers and career aspirations, and at the same time report being affected by anxiety disorders. In support of this, some studies (Goodwin et al., 2020; Adams et al., 2022) suggest that anxiety appears more common among young adults and has increased more rapidly among 18- to 25-year-olds than in any other age group (according to the study, anxiety diagnoses doubled between 2008 and 2018). The degree of uncertainty and anxiety related to the future can also vary depending on employment status. Being a student or already employed can have a significant impact on these perceptions (Muchacka & Dec, 2023). In particular, the period of transition from school to work represents a particularly stressful phase, characterized by anxiety, fear, and adjustment difficulties (Carstensen et al., 1999; Muchacka & Dec, 2023). This condition, if not adequately managed, can impair effectiveness in finding employment, handling job interviews, and acquiring job skills (Muchacka & Dec, 2023). Inadequate family support could further affect anxiety levels. For example, in the meta-analytic study conducted by Yap et al. (2014), a strong relationship emerges between anxiety and aversiveness, defined as parental hostility toward the adolescent expressed, for example, through criticism, punishment, and conflict. The importance of family and social support has been widely recognized in the literature (Greenblatt et al., 1982; Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Moreover, many studies have confirmed positive relationships between parental support and career adaptability, showing how parents can convey a sense of competence and improve their children’s career resources (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Creed et al., 2009; Hirschi, 2009; Tian & Fan, 2014; Soresi et al., 2014; Guan et al., 2015, 2016, 2018; Han & Rojewski, 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Particularly, parental psychosocial support is associated with career concern and confidence (Hlad’o et al., 2020), two key dimensions of career adaptability, along with career control and curiosity (Savickas, 2005). These dimensions act as mechanisms for developing skills, exploring career options and opportunities, and managing periods of transition or unemployment (Koen et al., 2012). Therefore, they are considered essential in managing uncertainty both during the transition into the world of work and for those already within it (Porfeli & Savickas, 2012; Hirschi et al., 2018).

1.1. The Role of Career Resources in Managing Uncertainty

Numerous studies show that career adaptability is a key resource in career decision-making, as it supports decision-making even in uncertain work environments (Porfeli & Savickas, 2012; Duffy et al., 2015; Rudolph et al., 2017; Hirschi et al., 2018; Stead et al., 2022), provides awareness that alternatives exist in every situation, and increases the ability to be flexible and adaptable to different circumstances (Martin & Rubin, 1995). These skills are particularly relevant in today’s work environment, which, due to its instability and changeability, could easily trigger feelings of fear and insecurity in people who feel unable to effectively control their context (Weinstein & Ryan, 2011; Krijgsman et al., 2017). For students, career adaptability is particularly relevant, as it enables them to effectively manage change, novelty, and uncertainty by coping with academic demands in a dynamic educational environment (Burns et al., 2018). Better career resources provide students with a greater likelihood of finding quality employment after graduation, making the transition from student life to a professional career crucial (Koen et al., 2012; Guan et al., 2013; Feng et al., 2023). The social context is also considered an important career resource (Marciniak et al., 2021). The support offered by parents, teachers, and peers fosters positive attitudes toward careers and greater involvement in decision-making (Hirschi et al., 2011), making these figures essential in providing growth opportunities (Perry et al., 2010). The presence of support from family, schools, and peers can promote career exploration and planning, while its absence can hinder these processes, affecting satisfaction with career choices (Hirschi & Freund, 2014). Studies have shown that those who experience high levels of parental support are more likely to engage in proactive career management behaviors, thereby improving their employability (Perry et al., 2010; Hirschi et al., 2011; Hirschi & Freund, 2014). The perception of being supported by parents also seems to have a direct and positive influence on the development of vocational interests and decisions (Meszaros et al., 2009) and improved professional self-efficacy (Gushue & Whitson, 2006). Parental involvement is crucial to students’ career explorations because it fosters the acquisition of confidence in one’s abilities and motivation to pursue career goals (Kanten et al., 2021). Liang et al.’s (2020) study, which examined the mediating role of adolescents’ consideration of future consequences in the association between parental career-related behaviors and adolescents’ career adaptability, suggests that interventions aimed at helping parents engage in supportive behaviors (such as participating in career exploration activities and providing information about different types of jobs) could be effective strategies for encouraging curiosity and confidence in future career choices. Conversely, parental criticism or negative evaluations seem to convey the message of not being able to meet their parents’ expectations (Lewis, 1992; Filippello et al., 2015), potentially leading to the development of feelings of shame and a fear of failure (Teevan & McGhee, 1972).

1.2. Parental Support or Criticism?

Social support is a contextual variable that significantly influences career development processes (Lent et al., 2000) and is a significant predictor of career development (Hirschi, 2009). Family environment influences students’ career choices (Young et al., 2002; Krumboltz, 2009; Savickas et al., 2009; Blustein, 2011), contributing to creating a supportive environment for them to explore their professional paths (Lee et al., 2013; Bae, 2017). Parents, as the primary sources of support, play a crucial role in shaping self-efficacy, professional expectations, and the development of professional interests, intentions, and goals (Kenny & Medvide, 2013). On the other hand, when parents exercise excessive psychological control, this can generate insecurity and the perception of being unable to handle situations independently, leading to reduced autonomy and increased anxiety when performing tasks (Vansteenkiste et al., 2005; Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010; Nanda et al., 2012; Schleider et al., 2014). The literature often refers to parental criticism, defined as negative comments made by parents, reflecting a perceived lack of support and a dysfunctional pattern in the parent–child relationship (Ammerman & Brown, 2018). Parental criticism also seems to have long-term effects, influencing individuals even during adulthood. For example, in Zhu et al.’s (2022) research, perceived parental criticism plays a significant role in shaping the emotional environment and is associated with various psychological difficulties. Specifically, the results suggest that parental criticism is more strongly linked to negative emotions, particularly anger, and that its impact may be intensified in emerging adults experiencing depression. Despite the significant interest in it, there are limited studies in the literature that have considered the effect of parental criticism on adults. In existing research, parental criticism is associated with the feeling of not meeting expectations (Frost et al., 1990; Frost et al., 1993) and, consequently, insecurity regarding one’s abilities (Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010; Costa et al., 2015). This may lead to a fear of failure, which in turn increases the likelihood of underperformance (Ahmad et al., 2013; Costa et al., 2015). The fear of failure is linked to expectations of shame, humiliation, or embarrassment when completing a task and is therefore associated with task avoidance behaviors (Chuang et al., 2022). Being an internally driven fear, it is closely related to a lack of motivation in pursuing performance goals (Sagar & Lavallee, 2010; Giel et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2021), decreased levels of well-being and academic performance (Manuel et al., 2020), increased levels of anxiety and depression (Yap & Jorm, 2015), and higher dropout rates (Sagar & Lavallee, 2010). Another study highlighted a link between the fear of failure and achievement goal orientation in an academic context, showing that individuals with a strong fear of failure pursue achievement goals mainly to obtain contingent rewards and avoid negative consequences (Michou et al., 2014). These findings suggest that the fear of failure may act as a mediator, negatively influencing academic adjustment (Michou et al., 2014). This is a relevant aspect when considering career adaptation and career choices, as the fear related to uncertainty about one’s future may influence career resources and, specifically, career confidence (Hirschi, 2009).

1.3. Aims

Based on the literature reviewed and the gaps that have emerged, this study aims to test the following research hypotheses:

H1.

Parental criticism negatively relates to career confidence directly and indirectly through the fear of an uncertain future.

H2.

The relationships between the variables differ based on being a worker or a student.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

Data collection took place in January 2024. The sample was composed of 310 participants, of whom 108 were students (34.8%) and 202 were workers (65.2%). As for the student sample, 76% were female and 24% male. In terms of age, 20% were between 15 and 18 years old, 70% were between 19 and 25 years old, and 10% were over 25 years old. As for the sample of workers, 72% were female and 28% male. Overall, 34% were between 19 and 27 years old, 20% were between 28 and 37 years old, 20% were between 38 and 50 years old, 23% were between 51 and 65 years old, and 3% were over 65 years old. Regarding education, 7% had a middle school diploma, 36% had a high school diploma, and 57% had a university degree. As for their employment type, 23% were self-employed, 57% were employees or office workers, 5% were entrepreneurs or managers, 4% were retired, and 11% preferred not to declare.

2.2. Measures

To assess parental criticism, 4 selected items from the Perceived Criticism Inventory (PCI; Apparigliato et al., 2007) were used. This scale, consisting of 11 items in total, assesses the level of experienced criticism by one’s parents and refers to both the present and the past, since both the present and past tenses are included in the wording of items. Examples of items include “My parents scold (or used to scold) me, saying I am incompetent” and “My parents say (or used to say) they are disappointed with the results I achieve”. Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s alpha for this survey was 0.80.

To assess the fear of an uncertain future, the Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory (PFAI; Conroy, 2001; Conroy et al., 2002) was used, specifically Cluster C, which measures the fear of having an uncertain future through 4 items. An example of an item is “When I am failing, it upsets my plan for the future”. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha for this survey was 0.84.

In the student sample, career confidence was measured using the 3-item career confidence scale (e.g., “I am confident that I will achieve my occupational goals”) from the Career Resources Questionnaire–Adolescent version (CRQ-A; Marciniak et al., 2021), in its Italian adaptation (Pace & Sciotto, 2023). Each item was presented as a statement, and participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely false) to 5 (completely true). The Cronbach’s alpha for this survey was 0.91. In the worker sample, the adult version of the same questionnaire (CRQ; Hirschi et al., 2018) was used (e.g., “I am capable of successfully managing my career”). The Cronbach’s alpha for this survey was 0.93.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 29 for descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and multi-group analysis were performed with Mplus 8. Measurement invariance was assessed by comparing the two samples based on their role (student or worker), and the goodness-of-fit indices were examined. Progressively more constrained models were tested and compared to assess the measurement invariance (configural, metric, scalar, and strict). Additional constraints were considered appropriate and maintainable if the chi-square of the model did not change significantly and if the decrease in the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) between adjacent models was less than 0.01. When measurement invariance was supported, structural invariance could be examined. Structural invariance could only be examined if measurement invariance had been supported. The bootstrapping method with 5000 replications was used to assess the significance of the indirect effects. The estimation method adopted was the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method. The goodness-of-fit was evaluated using the following criteria: χ2 likelihood ratio statistic, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with associated confidence intervals. RMSEA values lower than 0.06 and CFI and TLI values greater than 0.90 indicated an acceptable fit.

3. Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlations between the variables are presented in Table 1. The difference between the two samples examined concerns career confidence, which was found to be negatively and significantly correlated with parental criticism and the fear of an uncertain future in the student sample, but not in the worker sample, where the direction of the relationship is negative but not statistically significant. In both samples, although the values are significantly higher in the case of students, parental criticism was found to be positively associated with the fear of an uncertain future.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, correlations among study variables, and scale reliability (students sample N = 108; workers sample N = 202).

Table 2 shows the fit values of the two CFA models separately for each sample, the multigroup analyses to test for fit invariance, and the structural models for each sample. All models show excellent fit. Measure invariance analyses show that there is no significant item bias in the data, indicating that the measures can be compared across groups. Structural model analyses for single groups and across groups also show an excellent fit, confirming an invariant pattern of relationships between study variables in the student and worker samples. On this basis, subsequent analyses could be carried out.

Table 2.

Goodness-of-fit values of CFA models and multigroup test for measurement invariance (ML estimation; students sample N = 108; workers sample N = 202).

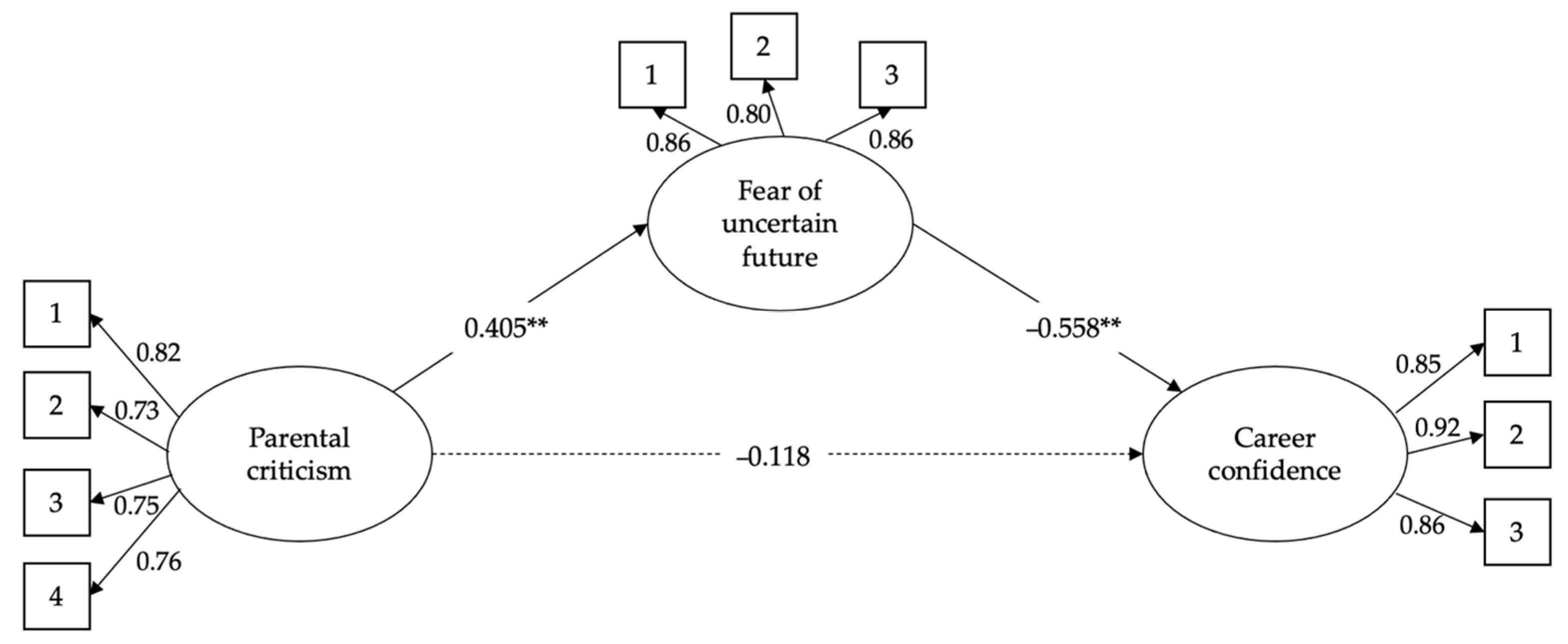

Figure 1.

The structural model for the students sample (N = 108). Note. ** p < 0.01.

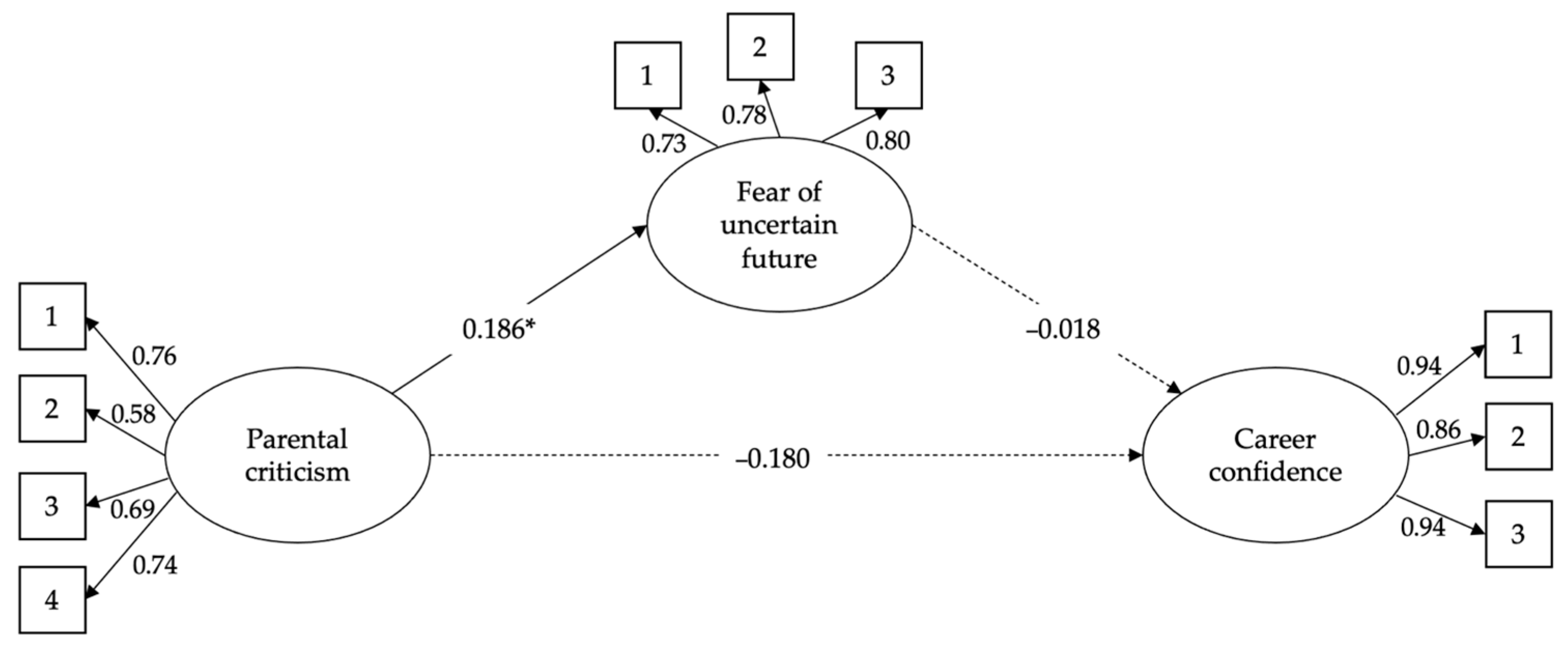

Figure 2.

The structural model for the workers sample (N = 202). Note. * p < 0.05.

As for the factor structure, all items saturate significantly on their factor, with factor loadings all above 0.50.

As for the relationships between the variables, as the correlation matrix suggested, the two models diverge significantly. In the student sample, fear of an uncertain future fully mediates the negative relationship between parental criticism and career confidence. As expected, parental criticism is positively related to fear of an uncertain future, which in turn is negatively related to career confidence. Parental criticism, therefore, does not act directly on career confidence, but only indirectly through the weight of the fear of an uncertain future. Hypothesis 1 is confirmed in the student sample, since the direction of the relationships between the variables is consistent with the hypothesis and mediation is total. The indirect effects are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Indirect effects using bootstrapping with 5000 replications (ML estimation; students sample N = 108; workers sample N = 202).

In contrast, in the sample of workers, the mediation model is not statistically significant, as the fear of an uncertain future did not show a significant association with career confidence. Another difference concerns the relationship between parental criticism and fear of an uncertain future, which, although statistically significant, has significantly lower values in the sample of workers than in the sample of students.

It can be concluded that Hypothesis 2 is fully confirmed, as there are substantial differences between the two samples based on occupational status.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to understand the relationship between perceived parental criticism, fear of an uncertain future, and career confidence, considering any differences related to occupational status (worker or student). It was hypothesized that the variables examined could interact differently based on whether one was still a student or already had a stable career.

The first research hypothesis was supported, confirming that parental criticism is negatively associated with career confidence through the effect of the fear of an uncertain future. As previously written, the literature has already widely supported the importance of parental support in career development and career adaptability among students. Several studies have shown that parental support can strengthen perceptions of competence, facilitate career adaptation (Creed et al., 2009; Guan et al., 2018), and positively affect career concern and confidence (Hlad’o et al., 2020) as well as career interests and decisions (Meszaros et al., 2009). This support is also reflected in improved employability, as greater family support is associated with proactive career management behavior (Hirschi et al., 2011; Hirschi & Freund, 2014). However, in the present study, the relationship between parental criticism and career confidence in the student sample is totally mediated by the fear of an uncertain future. In other words, parental criticism does not have a significant direct effect on career confidence, but it acts on confidence through the increase in the fear of an uncertain future. This finding is consistent with the literature on the effects of parental criticism on self-efficacy and with the idea that parental criticism or unrealistic expectations convey insecurity in general and in one’s professional abilities, specifically (Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010; Costa et al., 2015).

The hypothesized model was not statistically significant for the workers’ sample. Consequently, the second hypothesis, which assumed significant differences in the relationships between the variables depending on the role of student or worker, was also confirmed.

Although the association was stronger in the student sample, in both samples parental criticism was positively associated with the fear of an uncertain future. This result is also in line with Zhu et al.’s (2022) study, according to which parental criticism also influences the emotional environment of adults. However, there may be protective factors acting on workers (e.g., greater life experience) that students do not have. The difference in employment status between students and workers may influence how parental criticism impacts career confidence. Because of greater employment stability, workers tend to have lower levels of anxiety than students, who instead experience a greater sense of uncertainty and insecurity (Moghe et al., 2021). Although the relationship between parental criticism and the fear of an uncertain future is negative and significant in the sample of workers, a statistically significant relationship between parental criticism and career confidence did not emerge among them. This difference may be due in part to the fact that already having a job allowed the achievement of career goals, which might have had a positive effect on career confidence. Hence, the effect of criticism received in the past is still active on the generic fear of uncertainty related to one’s future, but no longer has the power to act on career-related confidence. Finally, the difference found between students and workers can be explained by evolutionary theories related to age and uncertainty management. According to the Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (Carstensen et al., 1999) and the Integration of Strengths and Vulnerability model (Charles, 2010), as individuals gain experience, they tend to focus on more emotional and immediate goals, whereas those with a broader and more uncertain future time perspective focus on goals related to long-term planning. This may explain why students, who are still shaping their career paths, are more vulnerable to uncertainty, while workers with more defined goals are less influenced by parental criticism.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to verify the cause-and-effect relationships between the variables. Secondly, although in issues related to parental support, fears, and confidence it is of crucial importance to detect individual perceptions, the exclusive use of self-reported data could lead to bias in the responses. Moreover, factors such as age may influence perceptions of parental criticism and fear of the future in ways that cannot be controlled, introducing potential confounding variables that may have influenced the study results. Thirdly, the sample was rather limited, not fully balanced, and obtained by convenience sampling, and this sets limits on the generalization of the results.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study highlight the weight of perceived parental criticism in worsening the insecurities already naturally present in students. This also has a spillover effect on career-related perceptions, in line with most theories of career development (Savickas, 2005) and career resources (Hirschi, 2009), that indicate that many of the constraints people might encounter in their careers are mental in nature. From this perspective, working on accepting failure rather than demonizing it may be a more effective strategy for promoting confidence in one’s abilities. We believe that the results of the present study may be useful in conveying the message that viewing failure as a constructive opportunity for learning and personal growth could foster greater adaptability to future professional challenges.

Our findings can lead to several practical applications, particularly for career counseling and educational programs aimed at supporting both students and early-career professionals in overcoming the negative effects of parental criticism and fear of an uncertain future. Since the perception of parental criticism negatively affects career confidence through the increased fear of an uncertain future, interventions in schools and universities should aim to help students develop resilience to external criticism. Many universities organize specific programs to improve the employability rates of their students, and these programs often include sessions that address social and environmental issues, but less often address issues related to cognitive constraints on career choices due to family experiences. Programs focusing on career adaptability and self-efficacy training could emphasize that setbacks, rather than limiting career potential, can serve as opportunities for growth. This could involve cognitive-behavioral techniques aimed at reframing negative thoughts, as well as workshops on emotional regulation to manage anxiety related to uncertainty. In general, these initiatives could help reduce the influence of external criticism and better align professional goals with personal values, leading to higher career satisfaction and confidence. It is also worth noting that the effect of parental criticism appears attenuated in the workers’ sample. This aspect highlights the need to implement a longitudinal research design among students to assess whether occupational experience can truly mitigate the burden of having an unsupportive family.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S. and F.P.; methodology, G.S.; data curation, C.M., G.S. and F.P.; writing – original draft preparation, C.M., F.P., G.C. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Palermo.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams, S. H., Schaub, J. P., Nagata, J. M., Park, M. J., Brindis, C. D., & Irwin, C. E. (2022). Young adult anxiety or depressive symptoms and mental health service utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(6), 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I., Vansteenkiste, M., & Soenens, B. (2013). The relations of Arab Jordanian adolescents’ perceived maternal parenting to teacher-rated adjustment and problems: The intervening role of perceived need satisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 49(1), 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammerman, B. A., & Brown, S. (2018). The mediating role of self-criticism in the relationship between parental expressed emotion and NSSI. Current Psychology, 37(1), 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apparigliato, M., Ruggiero, G. M., & Sassaroli, S. (2007). Il Perceived Criticism Inventory (PCI): Un nuovo strumento di valutazione del criticismo genitoriale. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale, 13, 275–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.-M. (2017). An analysis of career maturity among Korean youths using latent growth modeling. School Psychology International, 38(4), 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D. L. (2011). A relational theory of working. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E. C., Martin, A. J., & Collie, R. J. (2018). Adaptability, personal best (PB) goals setting, and gains in students’ academic outcomes: A longitudinal examination from a social cognitive perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S. T. (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 1068–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G. H., & Chan, D. K. (2008). Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 272–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y., Huang, T., Lin, S., & Chen, B. (2022). The influence of motivation, self-efficacy, and fear of failure on the career adaptability of vocational school students: Moderated by meaning in life. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 958334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, D. E. (2001). Progress in the development of a multidimensional measure of fear of failure: The performance failure appraisal inventory. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 14(4), 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D. E., Willow, J. P., & Metzler, J. N. (2002). Multidimensional fear of failure measurement: The Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(1), 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S., Soenens, B., Gugliandolo, M. C., Cuzzocrea, F., & Larcan, R. (2015). The mediating role of experiences of need satisfaction in associations between parental psychological control and internalizing problems: A study among Italian college students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P. A., Fallon, T., & Hood, M. (2009). The relationship between career adaptability, person and situation variables, and career concerns in young adults. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. D., Douglass, R. P., & Autin, K. L. (2015). Career adaptability and academic satisfaction: Examining work volition and self-efficacy as mediators. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q., Chen, X., & Guo, Z. (2023). How does role accumulation enhance career adaptability? A dual mediation analysis. Current Psychology, 42, 10426–10436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippello, P., Sorrenti, L., Buzzai, C., & Costa, S. (2015). Perceived parental psychological control and learned helplessness: The role of school self-efficacy. School Mental Health, 7, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. O., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Neubauer, A. L. (1993). A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 14(1), 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup Organization. (2023). Voices of Gen Z. perspectives on U.S. education, wellbeing and the future. Gallup, Walton Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Giel, L. I. S., Noordzij, G., Noordegraaf-Eelens, L., & Denktaş, S. (2019). Fear of failure: A polynomial regression analysis of the joint impact of the perceived learning environment and personal achievement goal orientation. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 33(2), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R. D., Weinberger, A. H., Kim, J. H., Wu, M., & Galea, S. (2020). Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008 e 2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 130, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenblatt, M., Becerra, R. M., & Serafetinides, E. A. (1982). Social networks and mental health: An overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 139(8), 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J. H., Callanan, G., & DiRenzo, M. (2008). A boundaryless perspective on careers. In J. Barling, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational behavior. Micro approaches (Vol. 1). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, P., Capezio, A., Restubog, S. L. D., Read, S., Lajom, J. A. L., & Li, M. (2016). The role of traditionality in the relationships among parental support, career decision-making self-efficacy and career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y., Deng, H., Sun, J., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Ye, L., Fu, R., Wang, Y., Zhang, S., & Li, Y. (2013). Career adaptability, job search self-efficacy and outcomes: A three-wave investigation among Chinese university graduates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y., Wang, F., Liu, H., Ji, Y., Jia, X., Fang, Z., Li, Y., Hua, H., & Li, C. (2015). Career-specific parental behaviors, career exploration and career adaptability: A three-wave investigation among Chinese undergraduates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y., Wang, Z., Gong, Q., Cai, Z., Xu, S. L., Xiang, Q., Wang, Y., Chen, S. X., Hu, H., & Tian, L. (2018). Parents’ career values, adaptability, career-specific parenting behaviors, and undergraduates’ career adaptability. The Counseling Psychologist, 46(7), 922–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushue, G. V., & Whitson, M. L. (2006). The relationship among support, ethnic identity, career decision self-efficacy, and outcome expectations in African American high school students: Applying social cognitive career theory. Journal of Career Development, 33(2), 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., & Rojewski, J. W. (2015). Gender-specific models of work-bound Korean adolescents’ social supports and career adaptability on subsequent job satisfaction. Journal of Career Development, 42(2), 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A. (2009). Career adaptability development in adolescence: Multiple predictors and effect on sense of power and life satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., & Freund, P. A. (2014). Career engagement: Investigating intraindividual predictors of weekly fluctuations in proactive career behaviors. Career Development Quarterly, 62(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., Nagy, N., Baumeler, F., Johnston, C. S., & Spurk, D. (2018). Assessing key predictors of career success: Development and validation of the career resources questionnaire. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(3), 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., Niles, S. G., & Akos, P. (2011). Engagement in adolescent career preparation: Social support, personality and the development of choice decidedness and congruence. Journal of Adolescence, 34(1), 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlad’o, P., Kvasková, L., Ježek, S., Hirschi, A., & Macek, P. (2020). Career adaptability and social support of vocational students leaving upper secondary school. Journal of Career Assessment, 28(4), 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanten, S., Kanten, P., & Yesiltas, M. (2021). The role of career self-efficacy on the effect of parental career behaviors on career exploration: A study on school of tourism and hotel management students. European Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 6(1), 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, M., & Medvide, M. B. (2013). Relational influences on career development. In S. D. Brown, & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 329–356). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Koen, J., Klehe, U.-C., & Van Vianen, A. E. (2012). Training career adaptability to facilitate a successful school-to-work transition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3), 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijgsman, C., Vansteenkiste, M., van Tartwijk, J., Maes, J., Borghouts, L., Cardon, G., Mainhard, T., & Haerens, L. (2017). Performance grading and motivational functioning and fear in physical education: A self-determination theory perspective. Learning and Individual Differences, 55, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumboltz, J. D. (2009). The happenstance learning theory. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(2), 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. H., Rojewski, J. W., & Hill, R. B. (2013). Classifying Korean adolescents’ career preparedness. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 13(1), 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. (1992). Shame: The exposed self. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y., Zhou, N., Dou, K., Cao, H., Li, J.-B., Wu, Q., Liang, Y., Lin, Z., & Nie, Y. (2020). Career-related parental behaviors, adolescents’ consideration of future consequences, and career adaptability: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(2), 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuel, G. L., Borrego, C. C., Granero-Gallegos, S., & González-Hernández, J. (2020). Effects of motivational climate on fear of failure and anxiety in teen handball players. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, J., Hirschi, A., Johnston, C. S., & Haenggli, M. (2021). Measuring career preparedness among adolescents: Development and validation of the career resources questionnaire—Adolescent version. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. M., & Rubin, R. B. (1995). A new measure of cognitive flexibility. Psychological Report, 76(2), 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meszaros, P. G., Creamer, E., & Lee, S. (2009). Understanding the role of parental support for IT career decision making using the theory of self-authorship. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(4), 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michou, A., Vansteenkiste, M., Mouratidis, A., & Lens, W. (2014). Enriching the hierarchical model of achievement motivation: Autonomous and controlling reasons underlying achievement goals. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 650–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghe, K. V., Kotecha, D., & Patil, M. (2021). COVID-19 and mental health: Impact on working people and students. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchacka, B., & Dec, B. (2023). Determinants of feelings of anxiety in students entering the job market. Labor et Educatio, 11, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, M. M., Kotchick, B. A., & Grover, R. L. (2012). Parental psychological control and childhood anxiety: The mediating role of perceived lack of control. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(4), 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, F., & Sciotto, G. (2023). Undergraduate students’ career resources: Validation of the Italian version of the career resources questionnaire. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J. C., Liu, X., & Pabian, Y. (2010). School engagement as a mediator of academic performance among urban youth: The role of career preparation, parental career support, and teacher support. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(2), 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfeli, E. J., & Savickas, M. L. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-USA Form: Psychometric properties and relation to vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C. W., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Career adaptability: A meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting responses, and adaptation results. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory. In Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sagar, S., & Lavallee, D. (2010). The developmental origins of fear of failure in adolescent athletes: Examining parental practices. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(3), 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In S. D. Brown, & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling (pp. 42–70). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. In R. W. Lent, & S. D. Brown (Eds.), Career development and counselling: Putting theory and research into work (2nd ed., pp. 147–183). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J. P., Duarte, M. E., Guichard, J., Soresi, S., Van Esbroeck, R., & van Vianen, A. E. M. (2009). Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 75(3), 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J. L., Vélez, C. E., Krause, E. D., & Gillham, J. (2014). Perceived psychological control and anxiety in early adolescents: The mediating role of attributional style. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(1), 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2010). A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: Proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Developmental Review, 30(1), 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soresi, S., Nota, L., Ferrari, L., & Ginevra, M. C. (2014). Parental influences on youths’ career construction. In G. Arulmani, A. Bakshi, F. Leong, & T. Watts (Eds.), Handbook of career development: International and cultural psychology (pp. 149–172). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Stead, G. B., LaVeck, L. M., & Hurtado Rua, S. M. (2022). Career adaptability and career decision self-efficacy: Meta-analysis. Journal of Career Development, 49(4), 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S., Eklund, R., & Arthur, C. (2021). Fear of failure in sport, exercise, and physical activity: A scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teevan, R. C., & McGhee, P. E. (1972). Childhood development of fear of failure motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21(3), 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y., & Fan, X. (2014). Adversity quotients, environmental variables and career adaptability in student nurses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Horst, A. C., Klehe, U., & Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M. (2017). Adapting to a looming career transition: How age and core individual differences interact. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Zhou, M., Lens, W., & Soenens, B. (2005). Experiences of autonomy and control among Chinese learners: Vitalizing or immobilizing? Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2011). A self-determination theory approach to understanding stress incursion and responses. Stress & Health, 27(1), 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M. B. H., & Jorm, A. F. (2015). Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalizing problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, M. B. H., Pilkington, P. D., Ryan, S. M., & Jorm, A. F. (2014). Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 156, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. A., Valach, L., & Collin, A. (2002). A contextual explanation of career. In M. B. Arthur, D. T. Hall, & B. S. Lawrence (Eds.), Handbook of career theory (pp. 206–224). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Y., Simons, J. S., & Goldstein, A. L. (2022). Dynamics of parental criticism and emerging adult emotional functioning: Associations with depression. Journal of Family Psychology, 36(8), 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).