Abstract

While male youths with mild intellectual disabilities (MIDs) display similar sexual development as their peers without MIDs, they experience higher rates of sexual and dating violence (SDV) and sexual risk behavior. Yet, little is known about effective gender-specific prevention for this population. Therefore, we conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a Dutch group-counseling program promoting psychosexual health and preventing SDV among male youths with MIDs aged 14–21 years—Make a Move+. The 120 participating male youths completed three questionnaires (baseline, post-test, 3-month follow-up; 77.5% retention). A subsample of 14 male youths and 5 trainers were interviewed pre- and post-program. With these multi-method, multi-informant data, we evaluated the program’s effectiveness on the six intended outcomes (attitudes (primary outcome), global self-esteem, skills, knowledge, SDV use and victimization, and sexual risk behavior) by (1) statistically comparing the self-reports of the intervention and control groups and (2) thematically analyzing interview data. We found limitations in the program’s integrity, and mixed evidence for the program’s effectiveness on attitudes, knowledge, skills, SDV use, and sexual risk behavior, and no evidence for effectiveness on global self-esteem or SDV victimization. We also found indications of adverse effects on SDV use and victimization. We offer suggestions for program refinement and future program evaluations.

1. Introduction

Young people with mild intellectual disabilities (MIDs), characterized by an IQ between 50 and 70, typically encounter cognitive and socio-emotional challenges (Patel et al., 2020). Despite these challenges, they generally show similar romantic and sexual development to their peers without MIDs (Baines et al., 2018; De Graaf et al., 2024). MIDs are the most prevalent disability worldwide, affecting about 1% of the adolescent population in Western countries (Patrick et al., 2021; Purugganan, 2018). This group exhibits specific vulnerabilities in psychosexual health, such as a heightened risk of unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and exposure to sexual and dating violence (Baines et al., 2018; Latvala et al., 2023). Sexual violence is defined as any non-consensual sexual activity, whether within romantic relationships, or between acquaintances or strangers (Graham et al., 2021, p. 439). This can range from unwanted touching and rape to the non-consensual sharing of explicit online content. Dating violence refers to psychological, physical, and sexual abuse between dating partners (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). These experiences are hereafter abbreviated as SDV. The consequences of SDV victimization among youth extend beyond immediate physical harm, to long-term physical, sexual, and mental health problems, as well as an elevated risk of re-victimization (Basile et al., 2020; Campo-Tena et al., 2024). Recognizing and addressing these risks is essential in supporting the healthy development of young people with MIDs.

Male youth with MIDs are particularly vulnerable to both using SDV, becoming victims of SDV, and engaging in risky sexual behaviors (De Graaf et al., 2024; Latvala et al., 2023; Verbeek et al., 2023a). Despite their evident need for psychosexual health education and support, they face significant barriers to receiving such education. Barriers include deflection of responsibility by caregivers and educators, and limited support for educators, which contributes to a non-comprehensive and normative education (Michielsen & Brockschmidt, 2021; Schaafsma et al., 2014). Moreover, the heterogeneity of this population requires tailoring to specific learning needs and accommodations that are not well integrated into the universal psychosexual health education (Michielsen & Brockschmidt, 2021). Also, whilst most youths rely on their social networks for information and support in their romantic and sexual development, youths with MIDs typically have limited social networks, which further increases their dependency on formal sexuality and relationships education (Frawley & Wilson, 2016; Gougeon, 2009). Thus, there is a critical need for programs aimed at promoting psychosexual health and preventing SDV and sexual risk behavior among male youth with MIDs.

Studies regarding sexuality education conducted specifically on male youth with MIDs are scant. Existing literature reviews on the related populations of youths and adults with MIDs highlight several gaps and limitations in the availability of programs and their content, as well as the evaluation of the studies (Brown et al., 2020; Gonzálvez et al., 2018; Hui, 2024; McCann et al., 2019; Paulauskaite et al., 2022; Perez-Curiel et al., 2023; Schaafsma et al., 2017; Stobbe et al., 2021). First, compared to girls and women, boys and men are less often included as participants in these programs. This indicates that currently, males with MIDs are underserved in supporting their psychosexual health. Second, existing programs predominantly focus on imparting knowledge about safe sex and risk avoidance, but lack a more comprehensive focus on other outcomes, such as relationships and pleasure. This is important, because youths with MIDs themselves express a desire to learn skills related to romantic relationships, sexual behaviors, and sexual enjoyment (Frawley & Wilson, 2016; Lofgren-Martenson, 2012). Moreover, most programs are not embedded in theories on behavioral change, psychosexual health promotion, or SDV prevention. This is important, because programs that lack theoretical underpinning are generally less effective (Scheirer, 2012). Also, some programs were insufficiently adapted for the cognitive and verbal challenges of people with MID. Third, very few studies evaluated specific programs for youths with MIDs compared to adults. Fourth, evaluation studies used mostly qualitative methods and/or the instruments lacked psychometrically robust measures, complicating the assessment of program effects. Finally, few evaluation studies investigated long-term outcomes.

A review of group counseling sexuality education programs to prevent the use of SDV among male youth in the general population has shown that these may be effective in changing attitudes and behaviors, but with small effect sizes and often only short-term effects on attitudes and lagged effects on behavior (Verbeek et al., 2023b). Regarding programs for youths with MIDs specifically, two evaluation studies were found reporting on the effectiveness of sexuality education programs aiming to promote psychosexual health and prevent SDV and risk behavior for female youth with MIDs. The first study evaluated the 17-session Iranian Sex Education Intervention for girls with MIDs (Hemati Alamdarloo et al., 2023). Results showed that girls who followed the program scored significantly higher at post-test than the control group on (some topics of) sexual knowledge. The second study evaluated the eight-session Dutch program Girls’ Talk+ for girls with MIDs (Van den Toren et al., 2022). The randomized controlled trial indicated that Girls’ Talk+ improved sexual knowledge and self-efficacy when negotiating contraception and indicating sexual desires and boundaries at post-test and three-month follow-up. However, positive effects on attitudes toward voluntary and equal sex at post-test had disappeared at follow-up. Moreover, effects on sexual risk behavior could not be assessed at 3-month follow-up, as too few girls reported sexual activity. In summary, although the few programs available appear promising, scientific knowledge on their effectiveness, specifically for male youth with MIDs, is lacking.

To expand our knowledge of effective promotion of psychosexual health and prevention of SDV and sexual risk behavior among male youth with MIDs, the aim of the current study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the Dutch group-counseling program Make a Move+ (MaM+), as it is currently implemented in practice. MaM+ is the only available program of its kind in the Netherlands for this specific population. The program was developed by Rutgers, the Dutch Centre of Expertise on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (https://rutgers.nl/, accessed on 18 December 2024). It is tailored to the unique needs of male youths with MIDs by using clustering of information, repetition of key content, and ‘hands-on’ methods (e.g., using clay to learn about anatomy). It takes a self-proclaimed positive approach to prevent the (1) use of SDV (i.e., perpetration), (2) SDV victimization, and (3) sexual risk behavior through improving the four intermediate outcomes: (1) attitudes toward positive, safe and acceptable sexual behavior and attitudes condoning SDV, (2) global self-esteem, (3) romantic and sexual interaction competency and peer pressure resilience skills, and (4) sexual knowledge. Apart from a pilot process evaluation conducted by the program developer in 2018, the integrity and effectiveness of the MaM+ program had not been previously rigorously evaluated after being implemented in a real-world setting.

To this end, we conducted a multi-method, multi-informant, block-randomized and controlled trial. Multi- or mixed-method evaluations of health-related and educational programs are currently considered the gold standard (Drabble & O’Cathain, 2015; Fetters & Molina-Azorin, 2020), specifically as they provide valuable in-depth insights into the real-world implementation and (perceived) effectiveness of programs on sensitive topics with hard-to-reach target groups, which are inherently complex (Banyard et al., 2023; Condomines & Hennequin, 2014; Michielsen & Brockschmidt, 2021). In this real-world pragmatic evaluation of MaM+, we considered the theoretical foundations and set-up of the program as well as its real-world integrity as something that we would investigate, and not influence. As the results on program effectiveness cannot be interpreted without information about program integrity, integrity will therefore provide a context in this effect evaluation. As Durlak (2015, p. 1124) stated, if we do not assess integrity, a program “may fail not because it lacks value, but because it was not implemented at a sufficiently high enough level to produce its effects”. This dual focus allows for assessing not only MaM+’s effectiveness in promoting psychosexual health and positive sexual behaviors, but to also understand how program integrity may aid in achieving these outcomes.

2. Method

2.1. Make a Move+ Program

MaM+ was developed by Rutgers in 2017. The ultimate goal of the program was to prevent SDV use (i.e., perpetration), SDV victimization, and sexual risk behaviors among male youths with MIDs, aged 14–21 years. MaM+ consists of eight weekly, 90-min-long group counseling sessions including group discussions, quizzes, role plays, and other exercises, facilitated by two trainers certified by Rutgers following a two-day training. The program is designed to be implemented in organizations supporting youth with MIDs (e.g., special secondary education or (residential) youth care). The program starts by setting ground rules, basic information on anatomy, and practicing flirting in a respectful way. The program builds up to sexuality-related topics in later sessions, including sexual pleasure, sex online, safe sex, and consent. For more detailed descriptions of the program goals, inclusion criteria, content, set-up and trainers, see Supplement S1.

MaM+ had multiple intended intermediate and long-term outcomes. The primary outcomes of this study are attitudes, namely (1) attitudes toward positive, safe, and acceptable sexual behavior, and (2) attitudes condoning SDV. This is based on the focus of the program on these goals according to the manual, and the theoretically expected and empirically established link between attitudes, SDV use, and SDV victimization, and sexual risk behavior among the general population of youth (Li et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2021; Morales et al., 2018), and those with MIDs (Verbeek et al., 2023a). The other intermediate outcomes (i.e., global self-esteem, sexual knowledge, and skills) were considered secondary, as required by The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT, Andrade, 2015; Schulz et al., 2011). We hypothesized that the effects on primary and secondary outcomes would appear immediately post-program. Regarding behavioral outcomes, studies on similar programs for the general population show varying long-term effects, some at 3 months, but most at 12 months (for a review, see Verbeek et al., 2023b). As it is unlikely that effects on behavior would be measurable for MIDs youth shortly post-program (Van den Toren et al., 2022), we deemed MaM+’s outcomes of preventing SDV and sexual risk behavior exploratory.

2.2. Design

This randomized controlled trial was part of the Move Up! Project (Verbeek et al., 2021), in which we evaluated two Dutch group-counseling programs: Make a Move (MaM) and Make a Move+ (MaM+). Whereas MaM was aimed at male youth aged 12–18 years old in vocational education and youth care, MaM+ was specifically tailored to male youth with MIDs. The Move Up! Project was funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), project number 5550002017. The hypotheses and methods for the Move Up! Project (Verbeek et al., 2021), as well as the specific aims and analysis strategy for the current study (Verbeek et al., 2024) were pre-registered on the Open Science Framework in November 2021 and May 2024, respectively.

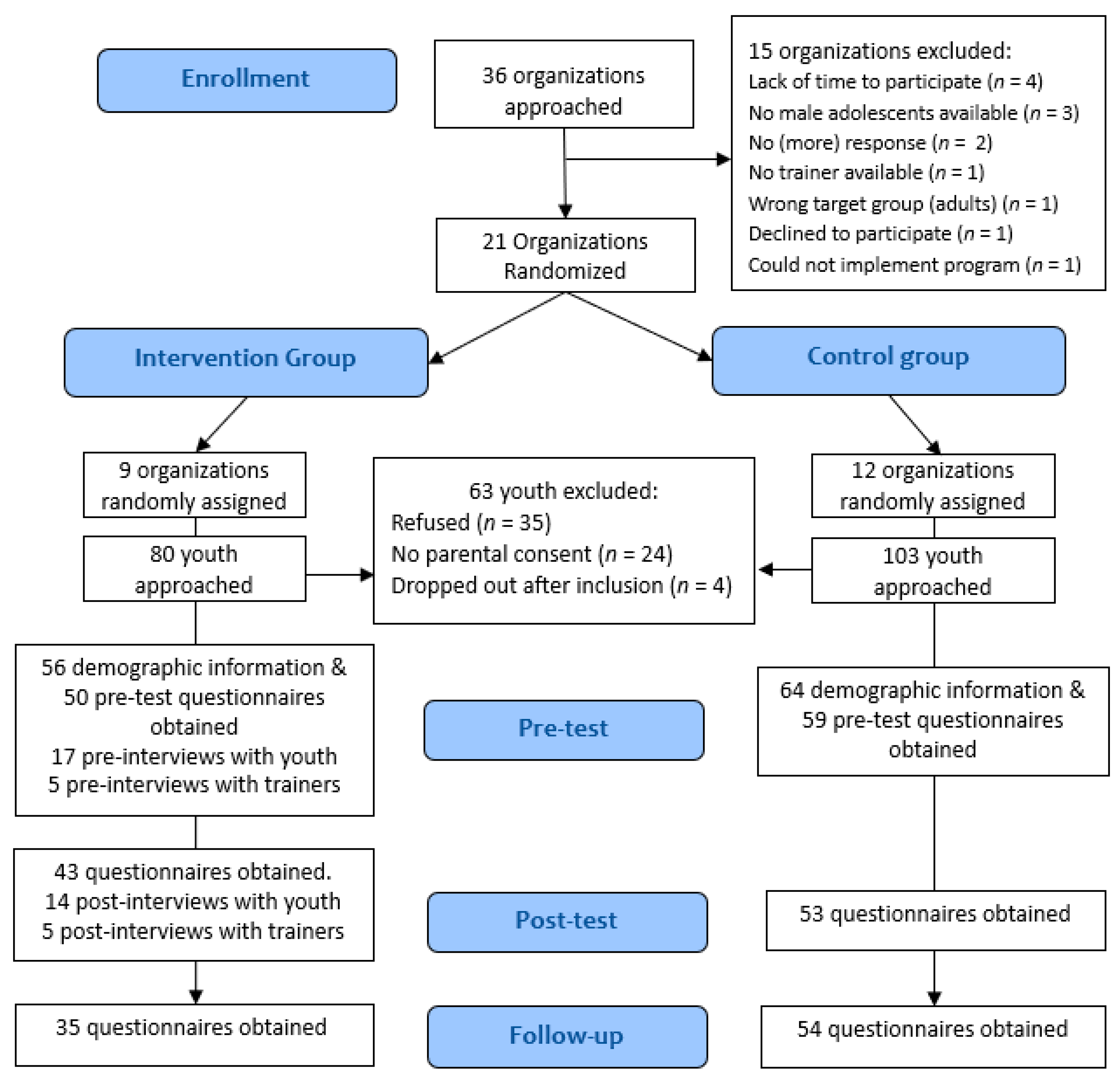

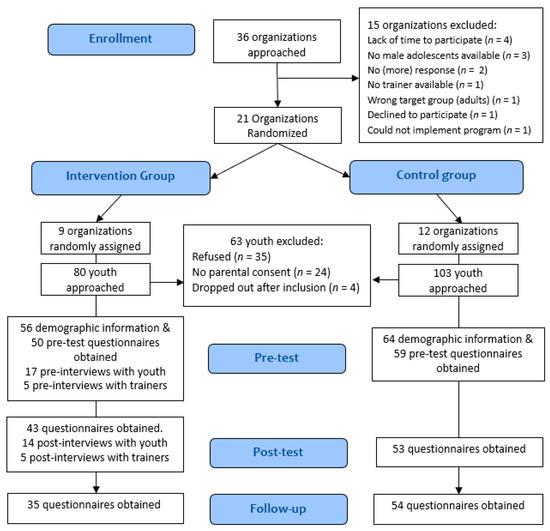

We conducted an unblinded, two-arm, cluster-randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of MaM+. Recruitment started in October 2020. Sample size was calculated a priori using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009), estimating a necessary 138 participants (69 per intervention arm) to detect small effects. Participating organizations were randomly assigned to the intervention group in which youth followed MaM+ during the study (i.e., between November 2021 and March 2023), or a waitlist control group, where youth received MaM+ after data collection ended, see Figure 1. Organizations that would take part in the project could differ on three different characteristics: (1) whether they were education or youth care or another type of organization, (2) whether the MaM+ trainer was internal staff or externally hired, and (3) whether they would be able to participate with one or two MaM+ groups during the course of the study. To ensure a balanced distribution of organization and trainer type, and cluster size over the intervention and control group, we used a stratified block randomization process. Hereto, organizations were first grouped into eight categories (i.e., based on these three characteristics, each with two options) before randomization. Two authors then conducted the randomization process per category by drawing lots together (i.e., four-eye principle). For example, for randomizing three schools with similar characteristics, we prepared four lots—two labeled “intervention” and two “control”—ensuring equal chances for assignment. One researcher would name for which organization a lot would be drawn, after which the other researcher would blindly draw a lot, and so on.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participating organizations and male youth. Note: youth in the intervention group participated in MaM+ between November 2021 and March 2023. Data were collected between October 2021 and July 2023. During the study, organizations were enrolled less frequently and therefore randomized individually to not slow down the enrollment process. This resulted in slightly unequal numbers of organizations between the intervention and control arms.

The main trial consisted of a baseline, immediate post-test, and 3-month follow-up measurement to quantitatively measure the outcomes using self-report questionnaires, see Figure 1. Pre- and post-program interviews were conducted with a subsample of intervention group youth and trainers. Recruiting a subsample was chosen to balance data completeness with feasibility of participation in a real-world setting, considering the already large burden placed on the school/youth care personnel and youth.

2.3. Procedure

We recruited organizations by contacting all trainers who had ever been certified to facilitate MaM+ via the program developer’s database with an information letter about the study, asking whether they and their organization were willing to participate. Next, we recruited trainers and organizations via school newspapers, LinkedIn, and already recruited trainers (i.e., snowball method). The inclusion criteria for organizations were that they (1) implemented or planned to implement the MaM+ program, (2) were able to implement MaM+ with at least one group of male youth with MIDs within the study timeframe, and (3) did not object to delaying MaM+ if randomized into the control group. After organizations agreed and MaM+ trainers signed informed consent, we randomized organizations by drawing lots. Two researchers conducted the process by drawing lots. For example, if three schools needed to be assigned, they prepared four lots—two labeled “intervention” and two “control”—ensuring equal chances for assignment. This method helped maintain evaluation rigor while achieving a fairly equal number of participants in each condition.

After randomization, intervention group organizations selected the eligible male youths to participate in MaM+, who were then invited to participate in the study. Control group organizations identified 6–16 male youths (i.e., equal to one or two MaM+ groups) to participate in the study.

Organizations selected the male youths—without involvement of the researchers—based on whether they considered them eligible for MaM+, as they would in a real-world setting, outside of the study. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the program included the following: an IQ of 50–70, at least some interest in romantic relationships and sexuality, no history of sexual offense or traumatic SDV experiences, and being able to function within a group setting. Fitting a real-world setting, some organizations applied other criteria (e.g., “All boys in year 3 follow MaM+”), see Table S2.1.

After selection, an organization contact person informed the eligible male youths through an informational video and letter from the researchers covering the study’s procedure and ethical standards, whereafter those agreeing to participate signed informed consent. For male youth under 16 or unable to fully understand consent—as estimated by the contact person—parents or legal guardians also signed informed consent. Those not participating in the study could still join MaM+.

From the intervention group, we recruited a subsample of six groups (i.e., three in schools and three in youth care) from which one trainer and a maximum of four male youths per group participated in two individual interviews: one before and one after the program. After the trainers agreed to participate, male youths from their MaM+ group were recruited via an additional informational video and letter from the researchers, after which they—and if applicable, their parents or legal guardians—signed informed consent.

The qualitative interviews were conducted using a semi-structured topic list by two researchers from Atria, Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History (https://atria.nl/, accessed on 18 December 2024): Researcher JK, a 29-year-old cis man of color with a bi+ sexual orientation and an educational university background in sociology, handled all the pre-interviews and post-interviews with the male youths and trainers except for post-interviews with the final intervention group. These were conducted by MS, a 30-year-old White cis heterosexual man with an educational university background in communication science and sociology. Interviews with male youths were conducted face-to-face or, if the youth left the organization, via telephone (n = 4), and lasted around 20 min (range 15–40 min). Interviews with trainers were held physically or online via Teams and lasted around 40 min. We audio-recorded the interviews and transcribed them verbatim for the qualitative analysis. The research protocol of Move Up! was evaluated by the Ethics Review Committee of the Department of Psychology, Education, and Child Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and approved (decision number 21-026).

2.4. Participants

2.4.1. Organizations

Twenty-one organizations participated in the study: five youth care organizations, twelve practical secondary education schools (i.e., schools for youths unable to attend regular secondary education and obtain a diploma, but possibly able to do practical work, mostly youth with MIDs), and four special education secondary schools (i.e., schools for youth with intellectual disabilities), see Table S1. Organization types were equally divided over the study arms.

2.4.2. Youth

A total of 120 male youths participated, aged 11 to 21 years (M = 15.02, SD = 1.46); 46.7% in the intervention group, see Figure 1). Characteristics of the male youths at baseline are presented in Table 1 and were described in Verbeek et al. (2023a). Regarding psychosocial functioning, assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, Van Widenfelt et al., 2003), 16.7% scored higher than 80% of male youths of the same age, and 30.3% scored higher than 90% of male youths of the same age on Total Problems (Vugteveen et al., 2022). Hence, 47% of our sample (55.1% of the intervention group) experienced at least some psychosocial problems.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participating male youth by condition at baseline.

2.4.3. Trainers

Twenty-seven MaM+ trainers were included in this study, of which 70.4% were female. They had M = 7.96 (SD = 5.66) years of experience working with the target group and had implemented the program 0–26 times, M = 4.04. Two trainers that we interviewed were also involved in the development of MaM+, and one of them also contributed to the certification of new MaM+ trainers at Rutgers. This may have impacted their relationship with or stance toward the program, although we have no evidence to support that this affected our results.

2.5. Program Integrity Evaluation

We assessed four elements of program integrity (Dane & Schneider, 1998; Lemire et al., 2023): (1) adherence (i.e., completeness of program delivery), (2) dosage (i.e., session length and number of sessions attended), (3) quality of delivery by trainers, and (4) participant responsivity (e.g., active participation and appreciation). See Point 12 in Supplement S1 for a description of the methods used.

2.6. Outcome Measures

2.6.1. Questionnaires

For details of the primary, secondary and exploratory outcome measures, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Quantitative and qualitative measures of program outcomes.

2.6.2. Interviews

As per our multi-method design, to supplement the quantitatively measured outcomes, we also assessed some program goals qualitatively using pre- and post-program interviews with male youth and trainers. Moreover, fitting a qualitative design, we asked open-ended questions to elucidate their perspectives on what youth had learned after the program without asking specifically about the a priori program goals, see Table 2.

2.7. Quantitative Analysis

To analyze the program’s effects using self-report questionnaires, we used intention-to-treat multilevel modeling in STATA version 17.0. Each outcome was tested separately, with scores on each timepoint (T0, T1, and T2) at Level 1, nested within individual youth at Level 2. This approach handles missing data at all timepoints, unequal spacing between measurements, and small samples well (Hox et al., 2017; Kwok et al., 2008; Twisk, 2021), allowing us to include all 120 participants in the model despite missing data on one or two timepoints. For all continuous outcomes, we ran Mixed Effects Linear (for normally distributed) and Poisson (for count variables) regression models to test intervention effects at immediate post-test and at 3-month follow-up, using the alternative repeated measures analysis recommended by Twisk (2021). Following this method, a regression model is specified with scores on the outcome at the three measurements as the dependent variable, and interaction terms between the intervention variable (intervention vs. control group) and T1 (post-test) and T2 (follow-up), but not T0 (baseline) as predictors. Results then represent the differences in change over time between groups, adjusted for the baseline scores. We used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to compare the groups on the dichotomous SDV outcomes, at immediate post-test and 3-month follow-up, controlling for baseline (Twisk, 2021). Finally, we conducted pre-registered robustness checks to see if clustering of participants within organizations would render different results

2.8. Qualitative Analysis

The interviews were analyzed in four steps by the first author and a research assistant, both with educational university backgrounds in developmental psychology and with 6 and 2 years of qualitative research experience, respectively. First, the research assistant openly coded all interviews using ATLAS.ti Version 24 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2023) to capture relevant information without imposing preconceived categories or themes (Boeije, 2014). Second, guided by our research questions, we used selective coding to identify codes related to participants’ accounts of the program’s effects, specifically examining changes in responses to effectiveness-related questions in the interviews before and after the MaM+ program, and specific program outcomes mentioned. Third, we organized emerging themes into pre-specified categories, namely the program goals. Fourth, we analyzed the differences and commonalities in responses to discern whether program effects were found in interviews with all male youth or trainers, selectively appeared among certain individuals, or were identified by one or two participants. We indicate this in the results as topics mentioned by ‘all’, ‘almost all’ (i.e., about 80%) or ‘most’ (i.e., more than half) of the participants, and more unique topics mentioned by ‘half’, ‘some’ (i.e., more than one or two, but less than half), or one or two participants. We translated interview quotes from Dutch to English to support and illustrate the findings.

Regarding positionality of the first author and research assistant analyzing the qualitative data, the research assistant’s neurodivergence (i.e., autism) and interest in gender and sexual diversity may have increased sensitivity to related issues, while the first author’s specialization in normative adolescent development may have heightened alertness to risk-focused and restrictive views on youth sexuality.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Flow and Baseline Characteristics

In total, 21 organizations were randomized, 12 to the control group and 9 to the intervention group, see Figure 1. As the recruitment started in October 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer organizations were able to participate within the project’s timeframe than expected, resulting in a smaller final sample size of N = 120 than the intended N = 138. Moreover, 27 male youths were lost to follow-up (22.5%). Attrition analyses indicated that these male youths more often appeared in the intervention group, in youth care, and sexually experienced at baseline than retained youth. Also, they had more positive attitudes toward positive and acceptable sexual behavior, and more sexual knowledge at baseline. However, they did not differ in age, religiousness, sexual orientation, romantic relationship experience, or experience with sexual education from retained youth. Characteristics and outcome scores for the intervention arms at baseline are presented in Table 1, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

M (SD) on the continuous quantitative outcomes at baseline (T0), direct post-test (T1) and 3-month follow-up (T2) by intervention arm.

Table 4.

SDV use behaviors and SDV victimization experiences at the different timepoints for the intervention and control groups.

3.2. Program Integrity

See Point 12 in Supplement S1 for a description of the results, summarized below.

3.2.1. Adherence

On average, trainers reported implementing 74.9% of the program’s manual content completely. Our observations indicted a lower adherence of 42.2%. The discrepancy between the trainer’s reports and our observations is mostly due to differences between scoring a program element as completely or partially implemented. Whereas trainers filled in checklists over entire exercises, the researchers used a more detailed scoring form, including separate elements of each exercise, and scoring the introduction and end of each session. Researchers observed that repeating elements at the end of exercises or sessions, and role plays were often skipped. The main reasons trainers mentioned for skipping elements were time limitations and the youths’ limited attention span. Lastly, participants were not always selected according to inclusion criteria and contra-indices (see Supplement S1 point 4).

3.2.2. Dosage

On average, M = 7.15 (SD = 1.41) of the eight MaM+ sessions were offered to youth. In eight out of thirteen intervention groups, all eight sessions were offered. Three intervention groups (two different organizations) compressed eight sessions into seven, and in two groups, the MaM+ program was terminated after four sessions due to organizational difficulties. Sessions lasted 70 min on average, instead of 90 min. Youth attended 75% of the program on average, M = 6.00 (SD = 2.30) sessions. More than half (64.7%) missed at least one session.

3.2.3. Quality of Delivery

Trainers were aware of most program goals, prepared, and adapted the program content and intensity to the group. Participating youth rated their MaM+ trainers’ skills highly (M = 4.94 on a scale of 1–6), assessed with the B-test questionnaire (Van Erve et al., 2007). Youth reported their trainers as being clear, engaging, reliable, respectful, and giving positive feedback. Interviews with trainers revealed that some focused mainly on specific goals such as promoting safe sex or preventing the use of SDV, and some highlighted certain outcomes they focused on, such as sexting. Moreover, observations showed that trainers sometimes struggled or chose not to address the male youths’ negative behaviors (e.g., sexist or homophobic comments), or expressed attitudes contradicting program goals (e.g., against abortion). As such, quality of delivery may have varied between trainers, with some program goals receiving less attention (e.g., improving global self-esteem and sexual/romantic interaction competency), or being undermined (e.g., reducing attitudes condoning SDV).

3.2.4. Participant Responsivity

After MaM+, the interviewed youth rated MaM+ positively (M = 7.9 out of 10), with few suggestions for improvement. However, the participants were unsure of what to expect from MaM+ upfront, as the 15 min individual intake conversations to increase motivation and check for contra-indices were rarely performed. Interviews and observations revealed that during MaM+, trainers spent much time managing the youths’ behavior, and that the youth sometimes had difficulty participating actively (e.g., low concentration), possibly as most groups included youth that did not meet inclusion criteria (e.g., some interest in love and sexuality; able to function in a group setting).

3.3. Program Effectiveness

Our findings relating to evidence for program effectiveness from multiple methods (i.e., questionnaires and interviews) and multiple informants (i.e., trainers and male youth) will be integrated below.

3.3.1. Primary Outcomes: Sexual Attitudes

Based on the youths’ self-report questionnaires, we found no significant differences in change over time between the intervention and control groups in attitudes toward positive and acceptable sexual behavior or attitudes condoning SDV, see Table 4. The interviews partially supported this, with most male youth reporting that their attitudes about sex had not changed due to the MaM+ program. Some male youths explained that the program had just reaffirmed their pre-existing beliefs about sex, which may be reflected in participating male youth scoring relatively high on positive attitudes and relatively low on attitudes condoning SDV at baseline, see Table 3. Nevertheless, some male youth did report changes in their attitudes toward sex after MaM+. When comparing pre- and post-program interview responses on what youth found important during sex, participants expressed increased positive attitudes toward communication, mutual respect, consent, mutual sexual pleasure, and safe sex practices. For instance, one boy who was not able to offer an opinion on what he found important about sex before MaM+, said in the after-interview:

“At first, I just thought: you fuck, you don’t explain much. […] But now I learned: you must know that the other person likes something else than you, and that they know what you like, […] that you both agree with it, and you don’t just do it randomly.” [Male youth, secondary education, 14 years]

Two other male youth mentioned increased conservative sexual standards for themselves, such as not having sex on a first date. However, none explicitly mentioned changed gender-related attitudes underlying SDV, such as adversarial sexual beliefs.

Finally, trainers believed that MaM+ challenged youth’s views and potentially influenced their thinking about relationships and sexuality, but most did not express strong conviction in the extent of this impact: “[…] here and there I think they at least […] can think slightly more nuanced about it.” [Trainer secondary education, female].

3.3.2. Secondary Outcomes

Sexual Knowledge. Based on the youths’ self-report questionnaires, we found no significant differences in change over time between the two groups in sexual knowledge, see Table 4. In the pre-program interviews, trainers mentioned that they considered increasing youths’ sexual knowledge, especially regarding safe sex, as the main goal of MaM+.

Afterwards, they believed knowledge about safe sex and realistic expectations of sex had effectively increased. Male youth echoed this in the post-program interviews, with almost all mentioning at least one thing they learned during MaM+, specifically on safe sex topics. Some also mentioned improved sexual vocabulary and having learned about anatomy. One of them stated: “It’s good that I participated, because first I knew nothing. Nothing at all really. And now I know a lot.” [Male youth, secondary education, 14 years]

On the contrary, some male youth indicated to have forgotten the things they had learned during MaM+. Two male youths explicitly said they did not learn anything new.

Finally, we observed a pattern in the interviews that was not directly related to increased sexual knowledge due to MaM+, but to increased ability to acquire sexuality-related information. Concretely, two trainers mentioned that after MaM+, youth would sometimes ask them or their mentor questions about sex, and two youth also mentioned that if they had any future problems or questions with sex, they would ask their parents.

Resilience to Peer Pressure. Based on the youths’ self-report questionnaires, we found no significant differences in change over time between the groups on peer pressure resilience, see Table 4. The interviews indicated mixed perceptions of the effects on this outcome across organizations. On the one hand, trainers from one organization indicated that improved resilience to peer pressure was a key outcome of MaM+ for the youth in their group, with one boy from that organization indeed acknowledging: “I don’t think I wouldn’t get carried away in it in all cases, but I think now I can better recognize for myself: Hey, this is peer pressure.” [Male youth, youth care, 17 years] On the other hand, a trainer in another organization noted that peer pressure remained a significant challenge for the youth in her group: “No we were not able to [obtain that goal] with these boys: they were still in the middle of that. No, I don’t think that that did anything with this group. Pick your battles, right?” [Trainer, secondary education, female]

Romantic and Sexual Interaction Competency. We assessed MaM+’s outcome of improved romantic and sexual interaction competency only in the interviews with male youth pre- and post-program. When asking youth which of the things they learned during MaM+ they would use, some mentioned that they learned how to flirt using different steps, how to communicate, and how to have pleasurable sex: “Things I will use? Well, how to arouse someone, how you, like how to do it with your fingers or your penis. And yes, those kinds of things, how it works and all.” [Male youth, secondary education, 14 years]. Some also indicated that they learned to “take it slow”, both during sex, and when dating. For instance, one explained that what he would do during sex was “Just step by step. […] Taking it slow and being careful. Not when the other person is in pain. Just gently.” [Male youth, practical education, 16 years] Moreover, when asking youth whether MaM+ contributed to being able to talk more (openly) about sex, most confirmed that it did: “You learned a lot. And then you can handle it [talking about sex] better, I think.” [Male youth, practical education, 14 years]

Additionally, most male youths reported higher perceived confidence in flirting, dating, and sexual interaction on a scale of 1–10 than they did before MaM+. When asking about this increase, most youth perceived that this was at least in part attributable to the MaM+ program. For instance, some of them perceived that their confidence in flirting/dating increased through learning different flirting steps during MaM+. Also, most attributed their increased confidence in sex to having gained more knowledge on how sex works during MaM+. At the same time, both those whose perceived confidence had increased, and those whose perceived confidence had lowered, mentioned that a lack of real-life experience with dating and sex hindered translation of their newly acquired knowledge to their perceived interaction competency: “Well of course you still don’t have experience, so you don’t know…” [Male youth, secondary education, 14 years] and another said, “I know how some things… how you should do some things and I know that I might not be that good at it. […] So that’s why I gave myself a lower grade.” [Male youth, secondary education, 14 years]

Global Self-esteem. Based on the youths’ self-report questionnaires, we found no significant differences in change over time between the groups on global self-esteem, see Table 4. In the interviews, we did not specifically ask about the perceived changes in global self-esteem, and neither youth nor trainers mentioned that they perceived changes in global self-esteem as an outcome of the program.

3.3.3. Exploratory Outcomes

Safe Sexual Behavior. Small numbers of sexually active youth precluded reliable analyses of changes in sexual risk behavior. Nonetheless, a comparison between the pre-and the post-program interviews indicated that the realization of the importance of safe sex had increased through the MaM+ program, with more youths after MaM+ expressing intentions to have safe sex and use condoms in the future. For instance, upon the question which of the things he learned during the program he would use, one replied “[I will] always have safe sex. When I contract an STI, what to do.” [Male youth, youth care, 17 years]

Use of Sexual and Dating Violence. See all outcomes for use of SDV in Table 5. Based on the youths’ self-report questionnaires, we found no differences between the groups in having used any type of SDV between pre- and post-test, or between post-test and follow-up. However, Poisson Mixed-effects Regression analyses indicated that between the pre- and post-test, intervention group youth reported having used more different types of SDV than control group youth, B = 0.79. 95% CI [0.06, 1.52], p = 0.033.

Table 5.

Results of mixed-model group comparisons of change over time on the continuous outcomes at post-test and follow-up, controlled for the baseline.

In contrast, in the post-program interviews, some youths specifically indicated that after MaM+ they would respect other people’s boundaries more: “[I would] just put that other person at ease. Enjoy it. Don’t try to stress too much. And just do your best and if that woman does not want to, don’t do it” [Male youth, secondary education, 14 years].

Some trainers also reported in the interviews that they had witnessed behavioral changes after MaM+, for instance that male youths treated girls and their peers with more respect.

“I am very glad that we have this program. Because sometimes, before we started here with the boys, they would not treat girls with respect.” [Interviewer asks whether the boys do treat girls with respect now] “Yes, for sure.” [Trainer secondary education, female]

However, most trainers expected effects on behavior more in the long term:

“Maybe not immediately. But in the long term, they think about it like ‘This [behavior] was okay, this was not.’ I think in a few weeks if they get sent a [nude] picture, they will still forward it. They will not immediately connect the dots. But hey, some are fourteen, fifteen years old. […] You hope when they are eighteen, something sticks, and [hope] they will act on it. […] I think because they are still fully in their pubertal development […] I don’t think they are already very considerate of the other person in that respect” [Trainer youth care, male]

Experiencing Sexual and Dating Violence Victimization. Based on youth self-report questionnaires, our GEE logistic analyses indicated that relatively more male youth in the intervention group reported SDV victimization at post-test (48.8% versus 38.2%), OR = 1.29, 95% CI [0.45, 2.13], p = 0.003 and follow-up (36.8% versus 29.1%), OR = 1.07, 95% CI [0.19, 1.95], p = 0.017 than male youth in the control group, see Table 4. Also, Poisson Mixed-effects Regressions indicated that at post-test, the intervention group reported more different types of SDV victimization than the control group, B = 0.62, 95% CI [0.10, 1.14], p = 0.019.

This may be explained by some youth mentioning in the interviews that they learned about their own boundaries. For instance, one who could not answer any questions about sex before the program, said after MaM+: “[I learned] what I don’t want. […] and if there is doubt, I just wouldn’t do it. If you both hesitate.” [Male youth, practical education, 14 years]

It is notable that none of the male youths or trainers talked explicitly during the interviews about the youths’ victimization experiences and whether they increased or decreased due to MaM+, suggesting that this may not have been a specific theme that stood out to them. Nevertheless, Table 4 of youth self-reports indicates that more male youth reported SDV victimization than use of SDV at all timepoints.

Moreover, out of the male youths who reported having used SDV, most reported victimization at the same time, suggesting overlap in these experiences and SDV victimization to be a present theme among this target group.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the Dutch group-counseling program Make a Move+ that is aimed at psychosexual health promotion and SDV prevention for male youth with MIDs. Consistent with the current best-practices for evaluating complex programs (i.e., with multiple outcomes and implemented in various contexts, with heterogeneous target groups) in real-world settings, we used multiple methods (i.e., quantitative and qualitative) to collect data with multiple informants (i.e., male youth and trainers) in a randomized controlled trial.

We found mixed evidence for the effectiveness of MaM+ on positive and SDV-related sexual attitudes, sexual knowledge, skills, and SDV use. The self-report questionnaires provided no evidence for effectiveness on these outcomes. However, post-program interviews with male youth and trainers suggested that they did perceive improvements in some of the assessed attitudes, sexual knowledge, and SDV use (e.g., intentions to respect boundaries). Moreover, youth themselves indicated improvements in safe sex intentions (e.g., condom use), and romantic and sexual interaction skills. We found no evidence for effectiveness on global self-esteem, or SDV victimization. Moreover, we found some indications for differential or adverse effects. In the interviews, some trainers and male youth perceived positive changes in peer pressure resilience, whereas others did not, or specifically mentioned that in their perception MaM+ had not affected this outcome. Regarding SDV use and SDV victimization, in the self-report questionnaires male youth indicated higher SDV use and victimization after following MaM+, compared to youth in the control group.

The finding that MaM+ did not lead to changes in the primary outcome of youth’ attitudes is in line with findings on the effectiveness of similar programs for boys in the general population (Orchowski, 2019; Verbeek et al., 2023b). This may be because the effects of a relatively short intervention do not outweigh the many other influences from media, friends, and the broader community in which these attitudes are formed (Flood, 2020). However, the fact that MaM+ did not lead to an increase in our secondary outcome of sexual knowledge is inconsistent with findings on the effectiveness of similar programs for girls (Hemati Alamdarloo et al., 2023; Van den Toren et al., 2022). This inconsistency may be explained by masculine (vs. feminine) norms prescribing boys to appear sexually knowledgeable and experienced and lacking interest in education. These norms may inhibit them from actively participating in group-based (sexuality) education programs (Brush & Miller, 2019; Flood, 2020; Rogers et al., 2021). At the same time, youths reported improvements in the secondary outcome of new skills for flirting, dating, and sex. This increase in perceived skills is noteworthy, because in general, people with intellectual disabilities have criticized the education they received as lacking instruction on how to handle romantic relationships and have (pleasurable) sex (Lofgren-Martenson, 2012; Schaafsma et al., 2017). Our finding of seemingly adverse effects on the exploratory SDV outcomes might be explained by an initial increased awareness of male youth’s own and others’ boundaries, with a decline only to be expected later (Porat et al., 2024). Some male youth also reported to not yet have enough experience with sex and dating to know how well they could apply what they had learned during MaM+. This fits with the finding that effects on behavioral outcomes in comparable programs targeting the general population are more pronounced after a longer time than directly post-program (Verbeek et al., 2023b). Longer follow-up times may be needed to evaluate the behavioral outcomes of SDV programs in future evaluation studies. For instance, Miller et al. (2020) observed effectiveness on behavioral outcomes of an SDV prevention program at 1-year follow-up that had not appeared at the 3-month follow-up.

Our results may be further explained by factors related to the program’s design, intended outcomes, and its integrity in a real-world context. First, the variability in (the effects on) peer pressure resilience, as noted by trainers, indicates that the program may currently insufficiently address the recognition of, and resilience to, peer pressure among some youth. Individuals with intellectual disabilities are particularly sensitive to the influence of others and struggle with self-reflection (Patel et al., 2020), suggesting that more time and effort may be needed to properly address this outcome.

Second, some (lack of) effects may be explained by program integrity. For example, our study results indicated that 42.2% of the program’s content was delivered as intended (i.e., adherence): the sessions were (partially) shortened or omitted, and most male youths missed sessions (i.e., low dosage); the quality of the delivery varied, where the trainers sometimes failed to address negative behavior during the sessions; and the youths were not always selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria set by the program developer. Different results may be found if the program was implemented with a higher program integrity (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). For example, components that are considered essential for retaining knowledge, such as repeating elements, and for developing skills, such as role-playing exercises, were often skipped. This may explain the lack of demonstrated effects on variables such as sexual knowledge. Moreover, youths within the groups varied in sexual knowledge, sexual experience, and cognitive functioning, which may have complicated the trainers’ complete and uniform program implementation while meeting the diverse needs of the participants.

Third, MaM+ targets multiple complex goals—including SDV use and victimization, sexual risk behavior, attitudes, global self-esteem, skills, and sexual knowledge—within a relatively short timeframe. Aiming at the three final goals, the program may thus have been too broad to achieve all goals. In contrast, its variant for normatively developing male youth called Make a Move, focuses on only one final goal (i.e., SDV use) within the same eight-week timeframe. This may, for instance, explain why we found effects on peer pressure resilience for Make a Move (Verbeek et al., in press), but not for MaM+ in the current study, as in Make a Move, more content may have addressed that goal.

Fourth, as a previous study on the development of sexuality education programs for people with MIDs indicated, these programs tend to be based on individual determinants of negative psychosexual health outcomes such as cognitive or emotional difficulties and limited sexual knowledge, instead of mechanisms for behavioral change (Schaafsma et al., 2013). Whereas the Make a Move program is grounded in socio-cognitive theory and focused on changing the use of SDV by focusing on social norms, self-efficacy, and intentions in addition to attitudes and skills, MaM+ focuses on (1) sexual knowledge and (2) global self-esteem instead. These factors may contribute less effectively to the intended program outcomes, specifically related to SDV. First, although the fact that people with MIDs generally lack sexual knowledge is well-known (Brkić-Jovanović et al., 2021; Rowe & Wright, 2017), research has not yet proven that improving sexual knowledge is associated with improved sexual behavior outcomes among people with MIDs (Schaafsma et al., 2017; Verbeek et al., 2023a). This may be related to the difficulties people with MIDs experience with transferring knowledge to behavior and retaining or reproducing new knowledge (Patel et al., 2020). The youths in our study also indicated difficulties with retaining and reproducing knowledge in the interviews. Second, prior empirical studies on the association between self-esteem and SDV indicate mixed evidence, with some suggesting that higher global self-esteem might even increase chances of using SDV (Bolívar-Suárez et al., 2022; Loinaz et al., 2021; Williams & McCarthy, 2014). The male youth in our sample already reported relatively high self-esteem, along with relatively high levels of SDV, and we also found no association between global self-esteem and experiences with SDV (Verbeek et al., 2023a). These findings suggest that increasing sexual knowledge and global self-esteem (i.e., goals not guided by a theoretically relevant mechanism of behavioral change) may not be the most effective strategy to improve psychosexual health and prevent SDV among male youth with MID.

4.1. Recommendations

Based on our results on MaM+’s integrity and effectiveness and the literature on effective psychosexual health promotion and SDV prevention in male youth (with MID), we put forward four recommendations for practice: (1) critically review the optimal dosage of programs such as MaM+, matching the needs of the target population; (2) ensure the relevance of each goal; and (3) ensure their measurability. That is, program goals should be attainable for the target group, within the set timeframe, and it should be possible to scientifically evaluate them.

First, regarding optimal dosage, systematic reviews of programs to prevent SDV and promote safe sexual behavior among the general populations suggest that longer programs (e.g., at least 11 sessions) tend to be more effective (DeGue et al., 2014; Kirby & Laris, 2009; Verbeek et al., 2023b). Considering the need for repetition of youths with MID’s and their difficulties with consolidation, one could suggest that even longer programs may be needed. In contrast, considering the fact that organizations often juggle time limitations, another possibility may be to focus on fewer goals, and more focused content. A previous study tested a longer versus shorter program targeting sexual health for adults with intellectual disabilities (Gil-Llario et al., 2023). Whereas the initial 16-week version proved effective, a shorter 10-week version equally affected sexual knowledge, and better affected behavior. Importantly, this shorter version targeted fewer goals and had a more focused content (e.g., only promoting condom use, instead of discussing all contraceptives). For youths with MIDs, it may thus be important to not only consider whether a program is sufficiently dosed, but also whether it is parsimoniously tailored to the people with MIDs’ ability to process information. This may also require looking into session length more specifically. As we found that the trainers often skipped elements, we observed that youth were more attentive in earlier parts of sessions, and due to implementation constraints within organizations, the optimal session length may need to be shorter (e.g., 45–60 instead of 90 min, see Ezhumalai & Marimuthu, 2021; Reddy, 2015).

Second, MaM+ has eight goals, which may not all be relevant for male youth with MIDs (e.g., global self-esteem). At the same time, some important goals may have been lacking attention, such as SDV victimization (Brush & Miller, 2019). This is important, because although MaM+ aimed to address both SDV use and SDV victimization, neither trainers nor participants identified this as a core program outcome. Yet, almost half of the youth in our sample had experienced victimization, particularly those who also used SDV. Ignoring male victimization and violence perpetrated by boys/men against each other (e.g., homophobic bullying) is a missed opportunity for SDV prevention, as these experiences can normalize both using, and experiencing violence (Brush & Miller, 2019). Importantly, SDV victimization is a known risk factor for future perpetration, both online and offline (DeLago et al., 2020; Richards & Gillespie, 2021; Sparks et al., 2023). Thus, specifically addressing victimization may more comprehensively prevent SDV by aligning with the youths’ lived experiences, as is often performed in explicitly gender-transformative programs, and could be useful for the MID population as well (see Dworkin & Barker, 2019; Limmer, 2010; Orchowski, 2019).

Third, it is important to assess whether all goals are measurable in program evaluations (Schaafsma et al., 2013). Behavioral outcomes (e.g., sexual risk behavior) may be difficult to assess among youths, as they can only be measured among those with any sexual experience since the end of the program. For instance, a recent study evaluating a gender-transformative program to increase psychosexual health among school-going adolescents found that effects on attitudes, sexual knowledge, and safe sex behaviors appeared especially among those that were or had become sexually active by the time of the follow-up measurement (Lohan et al., 2022). Therefore, when youth are not yet sexually active, it might be better to focus on skill development as a relevant outcome, rather than behavior. For instance, consent communication. As young men often rely on non-verbal cues and sexual scripts—including rape myths—over verbal communication during sex, they risk crossing boundaries (Cense et al., 2018; Jozkowski et al., 2014; Wilson, 2023). Yet, learning this skill is prudent, as a new Dutch law considers sexual harassment and any sexual activity without mutual, ongoing consent a criminal offense (Government of The Netherlands, 2024). Our study showed that MaM+ may aid male youths in developing this skill, as the youths reported increased intentions to use verbal communication, and to ‘take it slow’. Learning how to communicate about consent may prevent both the use of SDV, and SDV victimization (Ball et al., 2023; Scott & Graves, 2017). Future programs could explore how to further develop this skill, emphasizing the central importance of mutual consent in healthy safe and positive sexual interactions (McKinnon et al., 2024; Wilson, 2023). Including male youth in the process of developing the program may aid in its effectiveness (for an example, see Lohan et al., 2022).

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

While this study presented valuable insights into the effectiveness of the Make a Move+ program, it also has some limitations. First, a lack of existing, fitting, and validated measures of sexuality-related constructs for the target group of male youths with MIDs led us to adapt and shorten the instruments used and validated in general populations. Despite good reliability, we have not evaluated their validity after adaptation (for details, see Verbeek et al., 2023a). This is relevant for future effectiveness studies on such programs.

Second, using the youths’ self-report is an asset to this study, compared to the common practice of collecting data about the MID population from others (e.g., parents, caregivers, or teachers) who may not be fully aware of the youths’ private emotions, cognitions, and sexual experiences (Dekker et al., 2020; Hartini et al., 2021). To ensure understanding, we applied Language for all Principles (Moonen, 2021) to all materials, audiotaped the questionnaire to be listened to, and we were present during data collection to resolve any questions (for more details, see [View Only Link 1]). Yet, some youths may still have misunderstood or misinterpreted survey or interview questions, which sometimes became clear from the interview transcripts or during data collection. Research on instruments that suit MID populations is still in development (see Kooijmans et al., 2022), and is highly relevant for studying relational and psychosexual health promotion for this population. For behavioral concepts like interaction competency skills, it is particularly challenging to find appropriate (i.e., fitting, reliable and valid) measures. In our study, we used the qualitative interviews to gauge sexual and romantic interaction competency skills of the participating boys, which allowed us to ask follow-up questions and obtain a picture of which they felt they had learned. Yet, in future research, role playing or virtual reality technology may be explored to investigate these skills in a more valid and objective manner (Hakim & Hammad, 2021). However, it remains a challenge to measure skills that accompany future behaviors, as is often the case in studies on sexual behavior of young people (Kågesten & van Reeuwijk, 2021). Also, although we carefully specified our interview questions to balance obtaining information regarding perceived effectiveness of the program and yet not be leading, some participants may have responded overly positively about the program due to other reasons than learning something from it. This phenomenon has been described before as the ‘halo effect’ (Thorndike, 1920) where a person’s positive evaluation of one element of—in this case, the intervention (e.g., how fun the it was or how much participants liked the trainer)—may be extended to positive evaluations of other (unrelated) domains (Noor et al., 2023), in this case, experienced program effectiveness. This may explain some of the differences between the lack of effects found in the self-report questionnaires versus participants reporting perceived positive effects in the interviews.

Third, considering the population prevalence of male youth with MIDs in the Netherlands (i.e., around 1%) and compared to other research on MID populations, we recruited a relatively large study sample. Yet the sample size was smaller than intended, and retention was low, which limited the power to detect statistical effects. This means that our results need to be interpreted with caution. Future research could focus on person-specific designs and analyses (i.e., multiple measurements within the same person and focusing on within-person change) rather than variable-centered group comparisons. Such designs would also provide more in-depth information on what drives meaningful change in this population.

Fourth, as the youth and trainers expected the effects to appear in a few years rather than immediately post-program, our cluster RCT-design with a three-month follow-up may have been too short for a successful measurement of changes in the outcomes of SDV. Considering that most youths were not yet sexually active, nor planning to become so within a year, in the future effectiveness studies it may be relevant to repeat the outcome measurement at least one year later in young MID populations to evaluate the behavioral effects. Henceforth, developing more theoretical and evidence-based guidance on optimal follow-up periods for these programs that take into account young people’s developmental pathways and the variety in their levels of sexual experience, is needed.

5. Conclusions

This study was one of the first to evaluate an educational program aimed at promoting psychosexual health and preventing SDV and sexual risk behavior among male youth with MID, using a multi-method and multi-informant cluster RCT design. Overall, we found little evidence for the effectiveness of MaM+ in the context of its current implementation. Our results show mixed evidence for program effectiveness on the primary (i.e., attitudes), some secondary (i.e., knowledge and skills), and some exploratory outcomes (i.e., use of SDV and sexual risk behavior). On one secondary outcome (i.e., global self-esteem) we found no evidence for effectiveness. We also found indications of differential effects (e.g., on peer pressure resilience). Finally, we found some evidence of adverse effects on some exploratory behavioral outcomes (i.e., use of SDV and SDV victimization), where the male youths in the intervention group reported more such experiences after MaM+ than in the control group. Importantly, our study results also indicated specific challenges for program integrity that may currently negatively affect effectiveness, such as lowered adherence and dosage, variability in the quality of delivery, and the male youths’ difficulty to actively participate. Our findings warrant further optimization of program set-up, content, and integrity, followed by a comprehensive re-evaluation. Achieving relational and psychosexual health and well-being for youths with MIDs is a shared goal of researchers, practitioners, and program developers, and requires ongoing collaboration between these stakeholders. Uniting their scientific, experiential and practical expertise in an iterative process of development, evaluation and optimization will foster the development of sexuality education programs that effectively address the specific needs of male youths and their future romantic and sexual partners.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/youth5020042/s1, Supplement S1: TIDieR Checklist Make a Move+ (Harder et al., 2013). Supplement S2: Characteristics of the Participating Organizations and Trainers by Condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.V., D.v.d.B., M.P.C.M.L. and J.W.; Data curation, M.C.V. and E.A.W.S.; Formal analysis, M.C.V., D.v.d.B., E.A.W.S. and J.W.; Funding acquisition, D.v.d.B., M.P.C.M.L. and J.W.; Investigation, M.C.V.; Methodology, M.C.V., D.v.d.B., M.P.C.M.L. and J.W.; Project administration, M.C.V., D.v.d.B., M.P.C.M.L. and J.W.; Supervision, D.v.d.B., M.P.C.M.L., E.M. and J.W.; Validation, M.C.V., D.v.d.B., E.A.W.S. and J.W.; Visualization, M.C.V.; Writing—original draft, M.C.V.; Writing—review & editing, D.v.d.B., M.P.C.M.L., E.M., E.A.W.S. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of a larger project funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), project number 5550002017. This manuscript was drafted during a work visit to the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States, in collaboration with Prof. Dr. Miller. This work visit was funded by the Erasmus Trust Fund, a KNAW Van der Gaag Grant, and the Jo Kolk Studiefonds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Medical Ethical Testing Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) did not apply to the Move Up! study protocol, and that this study was therefore exempt from formal medical-ethical approval under Dutch law. Therefore, the full research protocol of Move Up! was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Department of Psychology, Education, and Child Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam (Application #21-086). We developed the study design, procedure, and instruments in close collaboration with an independent advisory committee consisting of academic researchers, practitioners, and Make a Move(+) trainers, all with relevant expertise for this project regarding its topic, target group and/or methodology.

Informed Consent Statement

After organizations enrolled in the study, participants signed informed consent (for questionnaires and interviews) or gave passive consent (for observations) for every part of the study they participated in, as did parents or legal guardians for youth under 16 years old and those whom the contact person considered them unable to fully understand consent themselves.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available (on request) upon termination of the Move Up! project (Estimated Summer 2025), see the projects’ page (https://osf.io/a82hr/, access on 18 December 2024) for more information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andrade, C. (2015). The primary outcome measure and its importance in clinical trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(10), 15598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baines, S., Emerson, E., Robertson, J., & Hatton, C. (2018). Sexual activity and sexual health among young adults with and without mild/moderate intellectual disability. BMC Public Health, 18, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, B., Hoefer, S., Faulkner, M., Requenes, A., Brooks, T., Munoz, G., Pacheco, E., Poland, C., Salmeron, C., & Zelaya, A. B. (2023). Innovation in sexuality and relationship education in child welfare: Shifting toward a focus on ongoing conversations, connection, and consent. Prevention Science, 24(S2), 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V., Edwards, K. M., Rizzo, A. J., Segura-Montagut, A., Greenberg, P., & Kearns, M. C. (2023). Mixed methods community-engaged evaluation: Integrating interventionist and action research frameworks to understand a community-building violence prevention program. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 17(4), 350–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K. C., Clayton, H. B., Rostad, W. L., & Leemis, R. W. (2020). Sexual violence victimization of youth and health risk behaviors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(4), 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeije, H. R. (2014). Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen (2nd ed.). Boom Onderwijs Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar-Suárez, Y., Gómez, J. A. M., Yanez-Peñúñuri, L. Y., Anacona, C. A. R., & Gómez, A. M. G. (2022). Self-esteem, body image, and dating violence in Colombian adolescents and young adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13–14), NP11628–NP11651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić-Jovanović, N., Runjo, V., Tamaš, D., Slavković, S., & Milankov, V. (2021). Persons with intellectual disability: Sexual behaviour, knowledge and assertiveness. Slovenian Journal of Public Health, 60(2), 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M., McCann, E., Truesdale, M., Linden, M., & Marsh, L. (2020). The design, content and delivery of relationship and sexuality education programmes for people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of the international evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, L. D., & Miller, E. (2019). Trouble in paradigm: “Gender transformative” programming in violence prevention. Violence Against Women, 25(14), 1635–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, M. R. (1980). Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(2), 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Tena, L., Larmour, S. R., Pereda, N., & Eisner, M. P. (2024). Longitudinal associations between adolescent dating violence victimization and adverse outcomes: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(2), 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cense, M., Bay-Cheng, L., & Dijk, L. v. (2018). ‘Do I score points if I say “no”?’: Negotiating sexual boundaries in a changing normative landscape. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 2(2), 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, March 9). Preventing teen dating violence in injury prevention and control. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/about-teen-dating-violence.html (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Condomines, B., & Hennequin, E. (2014). Studying sensitive issues: The contributions of a mixed approach. Revue Interdisciplinaire Sur Le Management et l’Humanisme, 3(5), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, A. V., & Schneider, B. H. (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review, 18(1), 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graaf, H., Oldenhof, A., Kraan, Y., Beek, T., Kuipers, L., & Vermey, K. (2024). Seks onder je 25e: Seksuele gezondheid van jongeren in Nederland anno 2023. [Sex under the age of 25: Sexual health among youth in the Netherlands in 2023]. Utrecht: Eburon. Available online: https://rutgers.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Boek-S25-2023-incl-cover.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- DeGue, S., Valle, L. A., Holt, M. K., Massetti, G. M., Matjasko, J. L., & Tharp, A. T. (2014). A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(4), 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Haas, S., van Berlo, W., Bakker, F., & Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2012). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence in the Netherlands, the risk of revictimization and pregnancy: Results from a national population survey. Violence & Victims, 27(4), 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, L. P., Visser, K., van der Vegt, E. J., Maras, A., van der Ende, J., Tick, N. T., Verhulst, F. C., & Greaves-Lord, K. (2020). Insight into informant discrepancies regarding psychosexual functioning of adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(2), 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deković, M., van Aken, M. A. G., Reitz, E., van de Bongardt, D., Baams, L., & Doornwaard, S. M. (2018). Project STARS (Studies on Trajectories of Adolescent Relationships and Sexuality. Data Archiving and Networked Services. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLago, C., Schroeder, C. M., Cooper, B., Deblinger, E., Dudek, E., Yu, R., & Finkel, M. A. (2020). Children who engaged in interpersonal problematic sexual behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 105, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from randomized controlled trials to mixed methods intervention evaluations. In S. N. Hesse-Biber, & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry (pp. 406–425). Oxford Library of Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A. (2015). Studying program implementation is not easy but it is essential. Prevention Science, 16, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, S. L., & Barker, G. (2019). Gender-transformative approaches to engaging men in reducing gender-based violence: A response to Brush & Miller’s “Trouble in paradigm”. Violence Against Women, 25(14), 1657–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmerink, P. M., van den Eijnden, R. J., Ter Bogt, T. F., & Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2017). A scale for the assessment of sexual standards among youth: Psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezhumalai, S., & Marimuthu, R. (2021). Social Group Work with Adults having Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 8(1), 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M. D., & Molina-Azorin, J. F. (2020). Utilizing a mixed methods approach for conducting interventional evaluations. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(2), 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M. (2020). Engaging men and boys in violence prevention. Men, masculinities and intimate partner violence (pp. 155–169). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foshee, V. A., Benefield, T., Dixon, K. S., Chang, L., Senkomago, V., Ennett, S. T., Moracco, K. E., & Bowling, J. M. (2015). The effects of moms and teens for safe dates: A dating abuse prevention program for adolescents exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(5), 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frawley, P., & Wilson, N. J. (2016). Young people with intellectual disability talking about sexuality education and information. Sexuality and Disability, 34, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Llario, M. D., Fernández-García, O., Huedo-Medina, T. B., Estruch-García, V., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2023). Analysis of the differential efficacy of the reduced version over the extended version of an affective-sexual education program for adults with intellectual disabilities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 52(1), 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzálvez, C., Fernández-Sogorb, A., Sanmartín, R., Vicent, M., Granados, L., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2018). Efficacy of sex education programs for people with intellectual disabilities: A meta-analysis. Sexuality and Disability, 36, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougeon, N. A. (2009). Sexuality education for students with intellectual disabilities, a critical pedagogical approach: Outing the ignored curriculum. Sex Education, 9(3), 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of The Netherlands. (2024). New justice and security laws as of 1 July 2024. Available online: https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2024/07/05/new-justice-and-security-laws-as-of-july-1-2024 (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Graham, L. M., Embry, V., Young, B., Macy, R. J., Moracco, K. E., Reyes, H. L. M., & Martin, S. L. (2021). Evaluations of prevention programs for sexual, dating, and intimate partner violence for boys and men: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 22(3), 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A., & Hammad, S. (2021, December 9–10). Use of virtual reality in psychology. Conference on Multimedia, Interaction, Design and Innovation (pp. 208–217), Warsaw, Poland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, A. T., Knorth, E. J., & Kalverboer, M. E. (2013). A secure base? the adolescent–staff relationship in secure residential youth care. Child & Family Social Work, 18(3), 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. (2012). Self-perception profile for adolescents: Manual and questionnaires (pp. 31–45). Univeristy of Denver, Department of Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartini, S., Chamidah, A. N., & Herini, E. S. (2021). Sexual behavior problems in adolescents with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(F), 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemati Alamdarloo, G., Moradi, S., Padervand, H., & Zare Dorahi, A. (2023). The effect of sex education intervention on sexual knowledge of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 41(3), 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S. F. E. I. (2024). Sexual education for adolescents and adults with intellectual disabilities: Systematic review. Sexuality and Disability, 42(1), 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozkowski, K. N., Peterson, Z. D., Sanders, S. A., Dennis, B., & Reece, M. (2014). Gender differences in heterosexual college students’ conceptualizations and indicators of sexual consent: Implications for contemporary sexual assault prevention education. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(8), 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kågesten, A., & van Reeuwijk, M. (2021). Healthy sexuality development in adolescence: Proposing a competency-based framework to inform programmes and research. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 29(1), 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, D., & Laris, B. A. (2009). Effective curriculum-based sex and STD/HIV education programs for adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 3(1), 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]