Purple-Colored Urine Induced by Cefiderocol: A Case Report and Comprehensive Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

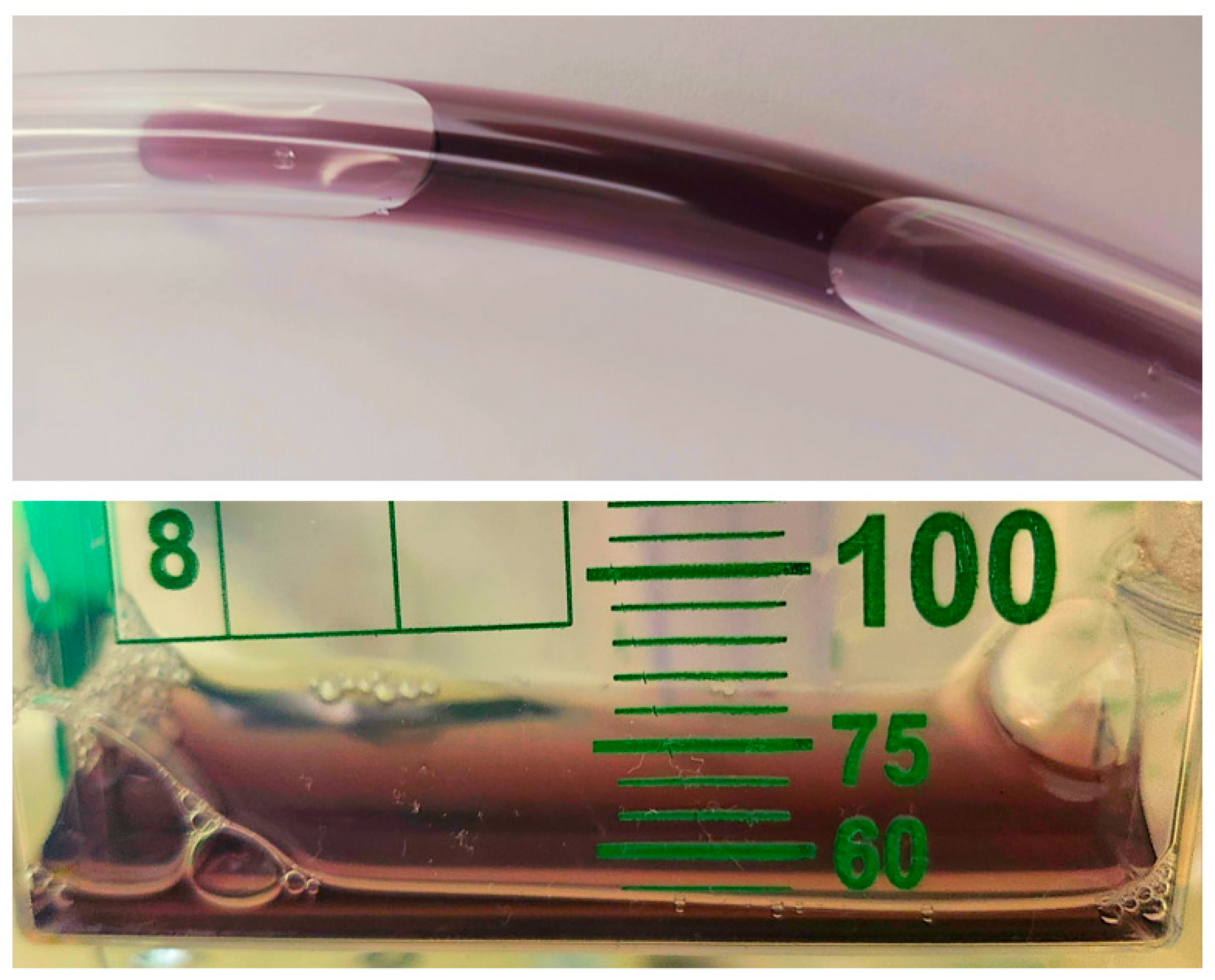

2. Case Presentation

3. Methods

4. Results

| First Author, Year of Publication | Patient Age (In Years) | Gender | Past Medical History | Presenting Symptoms | Source of the Infection | Isolated Organism/s | Isolation Site of Organism/s | Administered Antibiotics | Iron Supplementation/Blood Transfusion | Reported Urine Color/Time to Urine Discoloration | Resolution Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis et al., 2022 [6] | 63 | Female | Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis status post bilateral lung transplantation | Complication of the transplant surgery | Hospital-acquired pneumonia | MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Deep tracheal aspirate | Cefiderocol | IV Ferric gluconate 250 mg | Dark red/on day 14 of cefiderocol initiation; after first dose of iron infusion | Urine color normalized after completion of iron repletion |

| Shaik et al., 2023 [4] | 64 | Male | Down syndrome, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, seizure disorder, and chronic respiratory failure | Increased lung secretions and desaturation | Ventilator-associated pneumonia | DTR- Pseudomonas | Endotracheal aspirate | IV vancomycin, cefiderocol, IV amikacin, micafungin | No | Purple/on day 5 of cefiderocol initiation | Urine color normalized after cefiderocol discontinuation |

| Lupia et al., 2023 [8] | 82 | Male | Chronic kidney failure | Not documented | Nosocomial pneumonia | Carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter baumannii | Rectal colonization | Cefiderocol | No, but had an upper gastrointestinal bleeding | Dark brown chromaturia/on day 7 of cefiderocol initiation and day 1 of the bleeding | Urine color normalized 48 h after cefiderocol discontinuation |

| Smith et al., 2023 [10] | Early 70s | Female | DM complicated by peripheral neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease and bilateral diabetic foot ulcers | 1-week history of altered mental status and progressive purulent discharge from a non-healing diabetic foot ulcer on the right heel | Chronic osteomyelitis of the calcaneum of the right foot | XDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, XDR Acinetobacter baumannii, and Enterococcus faecalis | Tissue culture | IV vancomycin and meropenem. Then, switched to ampicillin-sulbactam and cefiderocol | No | Brown/on day 7 of cefiderocol initiation | Urine color normalized 3 days after cefiderocol discontinuation for another suspected side effect |

| Lescroart et al., 2023 [9] | 56 | Male | Myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock status post left ventricular assist device followed by heart transplant | Complication of the procedure | Left ventricular assist device driveline and pocket infection | CAZ-AVI resistant Pseudomonas aeruginona | Drive line site cultures | Caspofungin, and cefiderocol | One dose of IV ferric carboxymaltose 500 mg | Black urine/on day 22 of cefiderocol initiation; after first dose of iron infusion | Urine color normalized after 3 days despite the continuation of cefiderocol |

| Shapiro et al., 2024 [5] | 10 | Female | Refractory AML | Febrile neutropenia | Perianal cellulitis | NDM Escherichia coli | Blood culture | Cefepime, metronidazole and vancomycin, which was changed to cefiderocol, polymyxin-B and tigecycline | Received 1 unit of packed red blood cells on day 10 | Pinkish hue on day 2 of cefiderocol initiation then red on day 14 (4 days after receiving 1 unit of packed red cells) | Urine color normalized on the day of cefiderocol discontinuation |

| Shapiro et al., 2024 [5] | 12 | Female | Refractory B-cell ALL received CAR-T cell therapy with a course complicated by severe immunosuppression and graft failure | Respiratory failure | Pulmonary mucormycosis and bacterial pneumonia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Sputum culture | Cefiderocol (2 courses) | Received 3 units of packed red blood cells 6 days prior to starting cefiderocol | Reddish orange/on day 2 of cefiderocol initiation during both courses | Urine color normalized on the day of cefiderocol discontinuation |

| Shapiro et al., 2024 [5] | 5 | Male | Metastatic medulloblastoma | High fever | Not documented | Carbapenem-resistant, NDM-producing Escherichia coli | Blood culture | IV linezolid, cefepime and gentamicin, then meropenem, then cefiderocol | Received 3 units of packed red blood cells 6 days prior to starting cefiderocol | Purple/on day 2 of cefiderocol initiation | Urine color normalized on day 11 despite the continuation of cefiderocol |

| Present Report, 2024 | 56 | Female | Ischemic cardiomyopathy, HFrEF, advanced PAD, CVA, paraplegia, DM, recurrent UTIs | Foul smelling discharges from the sacral wound | Infected stage IV sacral pressure ulcer | Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii/nosocomialis, Proteus mirabilis | Wound culture | IV vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole then ampicillin/sulbactam, cefiderocol, and daptomycin | No | Purple/on day 3 of cefiderocol initiation | Given the poor prognosis patient was transitioned to comfort measures only. Urine began to clear one day after cefiderocol discontinuation |

5. Discussion

6. Clinical Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

References

- Singh, A.K.; Agrawal, P.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, O. Differentials of abnormal urine color: A review. Ann. Appl. Biosci. 2014, 1, R21–R25. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, L.M.; Reed, H.S. Hematuria. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2019, 46, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraireh, M.; Gharaibeh, S.; Araydah, M.; Al Sharie, S.; Haddad, F.; Alrababah, A. Violet discoloration of urine: A case report and a literature review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 68, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaik, M.R.; Shaik, N.A.; Hossain, S.; Yunasan, E.; Khachatryan, A.; Chow, R. Purplish Discoloration of Urine in a Patient Receiving Cefiderocol: A Rare Adverse Effect. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2023, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, K.; Ungar, S.P.; Krugman, J.; McGarrity, O.; Cross, S.J.; Indrakumar, B.; Hatcher, J.; Ratner, A.J.; Wolf, J. Cefiderocol Red Wine Urine Syndrome in Pediatric Patients: A Multicenter Case Series. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, T.C.; Arnouk, S. Dark Red Urine in a Patient on Cefiderocol and Ferric Gluconate. Ann. Pharmacother. 2022, 56, 1082–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karray, O.; Batti, R.; Talbi, E.; Ayed, H.; Chakroun, M.; Ouarda, M.A.; Bouzouita, A.; Cherif, M.; Slama, M.R.B.; Amel, M. Purple urine bag syndrome, a disturbing urine discoloration. Urol. Case Rep. 2018, 20, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupia, T.; Salvador, E.; Corcione, S.; De Rosa, F.G. Dark Brown urine in a patient treated with Cefiderocol. Infez. Med. 2023, 31, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Lescroart, M.; Noe, G.; Coutance, G. The black urine challenge. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2023, 25, e14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Foong, K.S. Cefiderocol-associated brown chromaturia. BMJ Case Rep. CP 2023, 16, e258207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Golden, A.R.; Zelenitsky, S.; Wiebe, K.; Lawrence, C.K.; Adam, H.J.; Idowu, T.; Domalaon, R.; Schweizer, F.; Zhanel, M.A. Cefiderocol: A siderophore cephalosporin with activity against carbapenem-resistant and multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Drugs 2019, 79, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69 (Supp. S7), S565–S575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, S.; Katsube, T.; Shen, H.; Tomek, C.; Narukawa, Y. Metabolism, excretion, and pharmacokinetics of [14C]-Cefiderocol (S-649266), a siderophore cephalosporin, in healthy subjects following intravenous administration. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 59, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Chaudhry, M.A.; Qureshi, N.; Cowley, B. Purple urine bag syndrome: An alarming hue? A brief review of the literature. Int. J. Nephrol. 2011, 2011, 419213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, P.; Merlo, J.; Beech, N.; Giles, C.; Boon, B.; Parker, B.; Dancer, C.; Munckhof, W.; Teng, H. The purple urine bag syndrome: A visually striking side effect of a highly alkaline urinary tract infection. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2011, 5, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Chamieh, C.; Liabeuf, S.; Massy, Z. Uremic toxins and cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease: What have we learned recently beyond the past findings? Toxins 2022, 14, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Chamieh, C. Influence Des Toxines Urémiques Sur La Morbi-Mortalité Cardiovasculaire Des Patients en Maladie Rénale Chronique Dans La Cohorte CKD-REIN. Université Paris-Saclay. 2024. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04625539 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Gautam, G.; Kothari, A.; Kumar, R.; Dogra, P. Purple urine bag syndrome: A rare clinical entity in patients with long term indwelling catheters. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2007, 39, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. VigiAccess. Available online: https://www.vigiaccess.org/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

| Category | Details | Examples/Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposing Factors | Patient-related conditions that increase risk | - Female sex - Dementia - Chronic constipation - Chronic renal disease - Alkaline urine - Increased urine bacterial load |

| Environmental Factors | Features of the medical setup that enhance PUBS risk | - Use of specific polyvinyl chloride-based urine bags |

| Catheterization | Type and duration of urinary catheterization | - Permanent/prolonged urinary catheterization (urethral or suprapubic) |

| Bacterial Causes | Specific bacteria capable of metabolizing indoxyl sulfate | - Proteus mirabilis - Klebsiella pneumoniae - Pseudomonas aeruginosa - Morganella morganii - Escherichia coli |

| Biochemical Pathway | Metabolism of tryptophan leading to pigment formation | - Tryptophan → Indole (intestinal bacteria) - Indole → 3-hydroxyindole (liver, via CYP2E1) - 3-hydroxyindole → Indoxyl sulfate (via sulfonation) - Indoxyl sulfate → Indirubin (red) and Indigo (blue) by bacterial enzymes in the catheter |

| Oxidative Process | Chemical oxidation leading to purple urine coloration | - Indirubin (red) + Indigo (blue) combine upon oxidation to create the characteristic purple hue |

| Medication-Related | Potential drug side effects | - Cefiderocol (antibiotic) |

| Urinary Environment | Local conditions in the urinary tract that facilitate pigment production and bacterial activity | - Catheter-associated biofilm formation - Stasis of urine - Alkaline pH enhancing enzymatic activity of bacteria |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bou Sanayeh, E.; Itani, H.; Moussa, E.; Glaser, A. Purple-Colored Urine Induced by Cefiderocol: A Case Report and Comprehensive Literature Review. Bacteria 2025, 4, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria4010009

Bou Sanayeh E, Itani H, Moussa E, Glaser A. Purple-Colored Urine Induced by Cefiderocol: A Case Report and Comprehensive Literature Review. Bacteria. 2025; 4(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria4010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleBou Sanayeh, Elie, Hadi Itani, Elie Moussa, and Allison Glaser. 2025. "Purple-Colored Urine Induced by Cefiderocol: A Case Report and Comprehensive Literature Review" Bacteria 4, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria4010009

APA StyleBou Sanayeh, E., Itani, H., Moussa, E., & Glaser, A. (2025). Purple-Colored Urine Induced by Cefiderocol: A Case Report and Comprehensive Literature Review. Bacteria, 4(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria4010009