Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, with increased home cooking and decreased restaurant dining, significantly altered seafood consumption patterns. By applying an ordered logit model to identify factors affecting seafood consumption during the pandemic, this study found that the shift in seafood consumption was driven by factors such as changes in meal preparation methods, more time spent at home, and shifts in financial situations. While take-out consumption boosted overall seafood intake, popular varieties saw a rise in home consumption, while high-end seafood suffered from decreased demand as consumers focused more on home dining. This study underscores the importance of supporting suppliers, restaurants, and retailers dealing with high-end seafood, as they face economic challenges due to reduced consumption. In summary, pandemic-induced restrictions on mobility led to a notable transition from restaurant-prepared seafood to home-cooked options, highlighting the need for targeted policies to aid affected sectors.

JEL Classification Codes:

D12; Q13; Q22

1. Introduction

Studies have revealed that confinement measures implemented during the COVID-19 era to restrict human mobility have shocked various agricultural markets [1,2,3,4]. This shock is known to have affected consumers’ food consumption behaviors. After the COVID-19 pandemic, many studies have investigated how the pandemic influenced food consumption behavior [5,6]. Seafood was no exception, and studies have indicated that a reduction in demand, related to human mobility restriction, decreased seafood prices during periods where confinement measures were taken to prevent the spread of the coronavirus [7,8,9,10].

Most previous studies analyzing the effects of the pandemic on seafood consumption use secondary market data, such as wholesale price and trade volume [4,9], or media reporting [7]. There is still limited research employing survey data to capture the manner in which people’s daily consumption behavior was affected during COVID-19. The research of Engel et al. [11] is one of the few studies surveying US consumers to investigate the changes in seafood consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that although overall seafood consumption did not increase during the COVID-19 era, consumers tended to buy seafood for at-home consumption rather than for dining out purposes. De la Iglesia et al. [12] also demonstrated from a Spanish sample that a general rise in all types of seafood consumption occurred in the year 2020 compared to 2019, which is related to more seafood being prepared at home.

Aruga et al. [10] found that the effects on high-end and popular seafood prices resulting from changes in human mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic varied. Their results indicated that high-end seafood, typically consumed more frequently outside the home, was significantly impacted by the decline in human mobility during the state of emergency (SOE) from April to May 2020. Umino and Matsui [13] similarly propose that sales of high-end marine products through e-commerce (EC) platforms have surged as a result of more individuals staying at home during the COVID-19 era. They anticipate that this rise in EC sales may be linked to a decreased expenditure for dining out. Ito et al. [14] examined food demand in the Tokyo metropolitan area between 2019 and 2020 using home scan data. They observed that the rise in expenditure on food consumption in 2020 was predominantly associated with home consumption, whereas spending on dining out decreased significantly. Their analysis of own-price elasticity and the expenditure elasticity of demand indicated that ingredients for home cooking, including seafood, became more interchangeable with dining-out options and more complementary with other ingredients in 2020. However, they grouped seafood into a single category, overlooking the diverse seafood consumption patterns inherent in the Japanese fish-eating culture, thus suggesting the need for further comprehensive analysis.

While per-capita consumption of seafood in Japan has been decreasing over the past two decades [15], Toyosu, Japan’s largest wholesale seafood outlet, continues to be the world’s largest wholesale fish market [16]. Japan is known for its rich biodiversity regarding the types of fish caught around the surrounding sea, and around 400 to 500 types of species are consumed for eating purposes in Japan [17]. Thus, the Japanese seafood market is highly liquid, with a wide variety of products, and it is imperative to understand how changes in consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic might have impacted this seafood market.

With this background in mind, the primary objective of this study is to examine the impact of changes in eating habits among residents of the Tokyo metropolitan area during the pandemic in regards to the frequency of their seafood purchases. The Tokyo metropolitan area was selected for this study due to its status as the most densely populated region in Japan, rendering it the area most severely affected by COVID-19. More specifically, we investigate how alterations in meal preparation methods, increased hours spent at home, and shifts in household financial situations have impacted the frequency of seafood consumption. The second objective is to assess whether there were disparities in the shifts in seafood consumption between high-end and popular varieties; high-end seafood is typically consumed more frequently in restaurants, at higher prices, whereas popular varieties are commonly prepared at home and are available at lower prices. The hours spent at home increased following the announcement of the first SOE in the Tokyo area in April 2020, leading to fewer people dining out and more individuals preparing meals at home [18]. Consequently, we anticipate that these changes in eating habits have affected the frequency of seafood consumption, resulting in a preference for seafood more commonly consumed at home during the pandemic.

The current study is one of the first studies to survey Japanese households to understand their consumption of seafood during the pandemic era. Examining consumer behavior concerning seafood to furnish insights into how shifts in eating habits impacted seafood consumption during a pandemic will aid policymakers and stakeholders in fortifying the seafood industry amid future pandemics. Furthermore, acquiring a deeper understanding of how consumers might shift from dining out to eating at home will provide a valuable contribution to consumer behavior research. The second contribution of the study is to deepen the understanding of how changes in human mobility affected consumption behavior using primary source data, since most previous studies only relied on secondary data. Lastly, since the Japanese seafood market encompasses a wide array of species, identifying variations in consumption patterns among different types of marine products provides valuable insights for mitigating adverse impacts on the seafood market related to future pandemics.

2. About the Survey Sample

An online survey was conducted between 31 July and 19 August 2023, using the platform of an online survey company, iBRIDGE Corp. A total of 2000 participants, aged between 20 and 80, and residing in the Tokyo metropolitan area at the time of the survey, were selected from the pool of 13 million individuals using iBRIDGE Corp. The samples were chosen based on the 2022 population estimates of Japan. From this initial 2000 samples, a second round of screening was conducted, based on specific criteria. First, we aimed to include respondents who purchase seafood in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Thus, we screened out individuals who had been away from the area during the past month. Second, we sought respondents who resided in the Tokyo metropolitan area during the initial SOE in May 2020. Third, we screened the respondents to include those who purchase seafood products several times a year or more. Finally, to ensure respondents were knowledgeable about their household’s seafood expenses, we screened for individuals who were the primary grocery shoppers in their households. After applying these screening criteria to conduct stratified sampling, a total of 850 respondents were obtained for analysis purposes.

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of the survey sample. Since Japan is one of the countries with the highest aging population, it is noticeable that over half of the survey sample were aged 55 or above. It is also evident that nearly 70% of the respondents were female. In Japan, household chores are predominantly undertaken by women, and this corresponds with the results of a household survey regarding chore distribution, indicating that in nearly 70% of participating households, it is the wife who decides the daily menu [19]. As we screened the respondents based on their awareness of their household seafood expenses, we believe that the higher percentage of female respondents in our sample is linked to women primarily being responsible for household meals in Japan.

Table 1.

Description of the demographic variables.

3. Methods

The econometric analysis is structured around Equation (1), which outlines the random utility model.

Here, denotes the utility derived by the ith survey respondent selecting choice j. signifies the deterministic utility, expressed as a linear combination of observable random factors.

Following the methods of Adibfar et al. [20], the random utility is assumed to be the frequency of seafood purchases of interest, defined as . With this assumption, represents the underlying latent variable, and is the highest rank order such that . Then, is defined as:

Here, represent the threshold parameters such that . Then, the ordered logit model can be expressed as:

where and are vectors of observed explanatory variables and unknown parameters, and is a random error term, with a mean 0 and a variance . Besides this ordered logit model, we also estimated the heteroskedastic ordered logit (HOL) model by extending the model by taking into account the heteroskedasticity in the error term, as follows:

where denotes the vector of explanatory variables affecting the variance of the ith observation, and is its unknown coefficients. For estimating the HOL model, we assumed all the demographic variables presented in Table 1 to be heteroskedastic.

Based on the above theoretical foundation, the factors affecting seafood consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic are analyzed using Equation (5):

For the dependent variable , we applied the frequency of buying high-end and popular seafood during the COVID-19 era. The details of the dependent variables are summarized in Table 2. “High-end COVID-19” and “popular COVID-19” denote the frequency of purchasing high-end and popular seafood during the pandemic. The lowest order, “never bought”, in the table represents those who did not purchase any high-end or popular seafood during the pandemic. High-end seafood is seafood with an average weekly price that is equal to or higher than JPY 800 (USD 5.4) per 100 g, such as bluefin tuna (kuro maguro), Japanese tiger prawn (kuruma ebi), and sea urchin (uni). Popular seafood is seafood with an average weekly price that is equal to or less than JPY 400 (USD 2.7) per 100 g, such as horse mackerel (aji) and sardine (iwashi) We differentiate between high-end and popular seafood as separate entities due to their distinctions in each consumption setting. Moreover, we rule out the notion that meat acts as a substitute for seafood in this study. This is supported by Ito et al. [14], who demonstrated, through their analysis conducted in 2020, that meat did not substitute for seafood. Table 2 shows that the percentage of people who did not buy seafood during the COVID-19 era was much higher for high-end seafood compared to popular seafood. This suggests there might have been a shift from high-end seafood to popular seafood during the pandemic.

Table 2.

Description of the dependent variables.

To ensure the reliability of the findings from consumption models during the pandemic era, we conducted additional analyses on models regarding the frequency of seafood consumption around the month when the survey was conducted, between 31 July and 19 August 2023. For this analysis, we utilized the dependent variables “high-end now” and “popular now”, each also comprising four ordinal categories.

To account for the heterogeneity of demographic backgrounds among respondents, we included demographic variables, encompassing age, gender, and parental status, denoted as demographics. As it is known that the cooking and shopping behaviors of consumers have changed during the pandemic [20,21], we also consider the changes in these aspects during the pandemic. Cooking includes whether the purchased seafood was consumed raw, boiled, or grilled. Preparation comprises the frequency of eating outside the home, using a delivery service, buying take-out meals, and cooking at home. Additionally, we examine how alterations in human mobility during the pandemic have influenced seafood consumption, as indicated by previous studies demonstrating that extended hours of remaining home have affected seafood prices [10,13]. To integrate this effect into our model, we incorporate mobility as a variable to account for the fluctuations in hours spent at home during the pandemic. Lastly, the monetary component encompasses changes in income, expenditures on food consumed at home, and expenditures for dining out, as COVID-19 is recognized to have impacted individuals’ income and consumption patterns [21,22]. The description of these variables is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of the control variables.

Table 3 shows that the percentage of people who ate out decreased during the COVID-19 era, suggesting that fewer people dined out during the pandemic. Meanwhile, more people cooked at home, and spending on home-cooked meals tended to increase during this period.

Finally, as a robustness test, we also estimated binary logit models for high-end and popular seafood products to examine the impact of the pandemic on the specific types of seafood consumption. The same independent variables were included in this binary model as those included in Equation (5), with the dependent variable indicating whether the individual purchased that type of seafood during the pandemic era. For high-end seafood, we analyzed non-frozen bluefin tuna, eel, and Japanese tiger shrimp within the high-end seafood category. Similarly, we tested the model for non-frozen horse mackerel, mackerel, and salmon to ascertain how each specific type of seafood within the popular seafood category was affected during the pandemic. These three seafood products ranked as the top three in terms of the percentage of respondents who reported in the survey that they had purchased them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Before finalizing the estimation models, we estimated the variance inflation factor (VIF) among the independent variables. The VIFs ranged between 1.10 to 2.05, ruling out the possibility of multicollinearity.

4. Results

4.1. Ordered Logit Model Estimation

We surveyed 850 respondents residing in the Tokyo metropolitan area during the first SOE period, which occurred between April and May 2020. An ordered probit model was applied to examine the potential effects of demographic background, cooking methods, meal preparation, hours spent at home, and financial conditions on seafood consumption frequency during the COVID-19 pandemic. The estimation results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ordered logit estimation.

First, among the demographic variables, age exerted a positive impact on high-end seafood consumption, suggesting that older individuals tended to purchase more high-end seafood during the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding aligns with the tendency for older people, particularly those aged over 60, to have a higher rate of seafood purchases compared to the younger generation in Japan [23]. Female respondents expressed a lower rate of seafood consumption during the pandemic. This might be attributed to the higher incidence of part-time female workers compared to males losing their jobs during the pandemic [24], leading them to reduce seafood consumption to save money. Table 4 also suggests that respondents who were married showed a higher rate of seafood consumption. This observation may imply that during the pandemic, individuals living within a family unit spent more time together and shared seafood meals, possibly due to the stay-at-home restrictions.

Second, the table illustrates that both high-end and popular seafood were more likely to be prepared either raw or grilled, with less spending on boiled seafood during the COVID-19 pandemic. This trend could be attributed to changes in meal preparation habits during the COVID-19 era. Individuals purchasing seafood for takeout purposes exhibited a higher consumption rate for high-end seafood, and since seafood for take-out purposes is more commonly prepared raw or grilled, it suggests that more people tended to opt for take-out meals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Third, the hours spent at home had a positive effect on the frequency of popular seafood consumption during the pandemic. This suggests that people consumed seafood more frequently at home rather than dining out during the state of emergency (SOE) period. This is likely related to the impact of the SOE request, which imposed restrictions on the operating hours of restaurants and bars, prompting people to return home earlier than they would have during periods before the SOE was announced.

Fourth, Table 4 also shows that individuals’ changes in their financial situation during the pandemic influenced seafood consumption. Those who allocated more of their expenses to eating at home experienced a decrease in the frequency of consuming high-end seafood. This outcome likely reflects a transition from dining out to eating at home, as high-end seafood is typically consumed at restaurants.

The estimation of the average marginal effects of the ordered logit model presented in Table 5. Table 6 further validates the aforementioned findings, indicating that older and married individuals increased their consumption of high-end seafood, while a greater preference was observed for raw and grilled seafood compared to boiled seafood during the pandemic. It is discernible that people who bought take-out food more frequently during the pandemic exhibited a higher frequency of seafood purchases. The impact of an increase in stay-at-home hours on popular seafood consumption shifted from negative to positive when individual purchase frequency remained the same or increased when compared to the pandemic era. Lastly, an increase in expenses spent on meals eaten at home had a negative effect on the frequency of popular seafood consumption.

Table 5.

Average marginal effects for the high-end seafood.

Table 6.

Average marginal effects for the popular seafood.

4.2. Robustness Tests

We also tested the same model using the heteroskedastic ordered logit model, as illustrated in Table 7. Here, the direction of the coefficient mostly aligned with that of the ordered logit model, while the eating out expense became significant at the 10% level for the popular seafood model during the pandemic. This negative sign for the eating out expense coefficient regarding popular seafood consumption indicates that when individual spending on eating out increased, the frequency of consuming popular seafood decreased. This could suggest that when people allocate more money to eating out, the frequency of purchasing popular seafood declines.

Table 7.

Heteroskedastic ordered logit model estimation.

Finally, Table 8 shows the result of the robustness test to examine how factors investigated in this study affected the high-end and popular seafood consumption by type of product. It is evident from the tuna and eel models that older individuals tended to purchase high-end seafood, while females consumed less during the pandemic. Meanwhile, it can be observed from the mackerel and salmon models that individuals with higher incomes tended to purchase popular seafood during the pandemic. The table also reveals that individuals preferred raw or grilled over boiled seafood when purchasing high-end seafood. An increase in takeout consumption was only significant at the 10% level, but it had a positive effect on high-end seafood consumption. Changes in the hours of staying at home did not become significant in any of the models. Based on the horse mackerel and mackerel models, it appears that there was an increase in popular seafood consumption among individuals whose income rose during the pandemic. Finally, similar to the results of the ordered logit model, an increase in expenditure on dining at home tended to have a decreasing effect on tuna and Japanese tiger shrimp consumption, indicating that the shift from dining out to eating at home during the pandemic reduced high-end seafood consumption.

Table 8.

Logit model estimation for the type of seafood purchased.

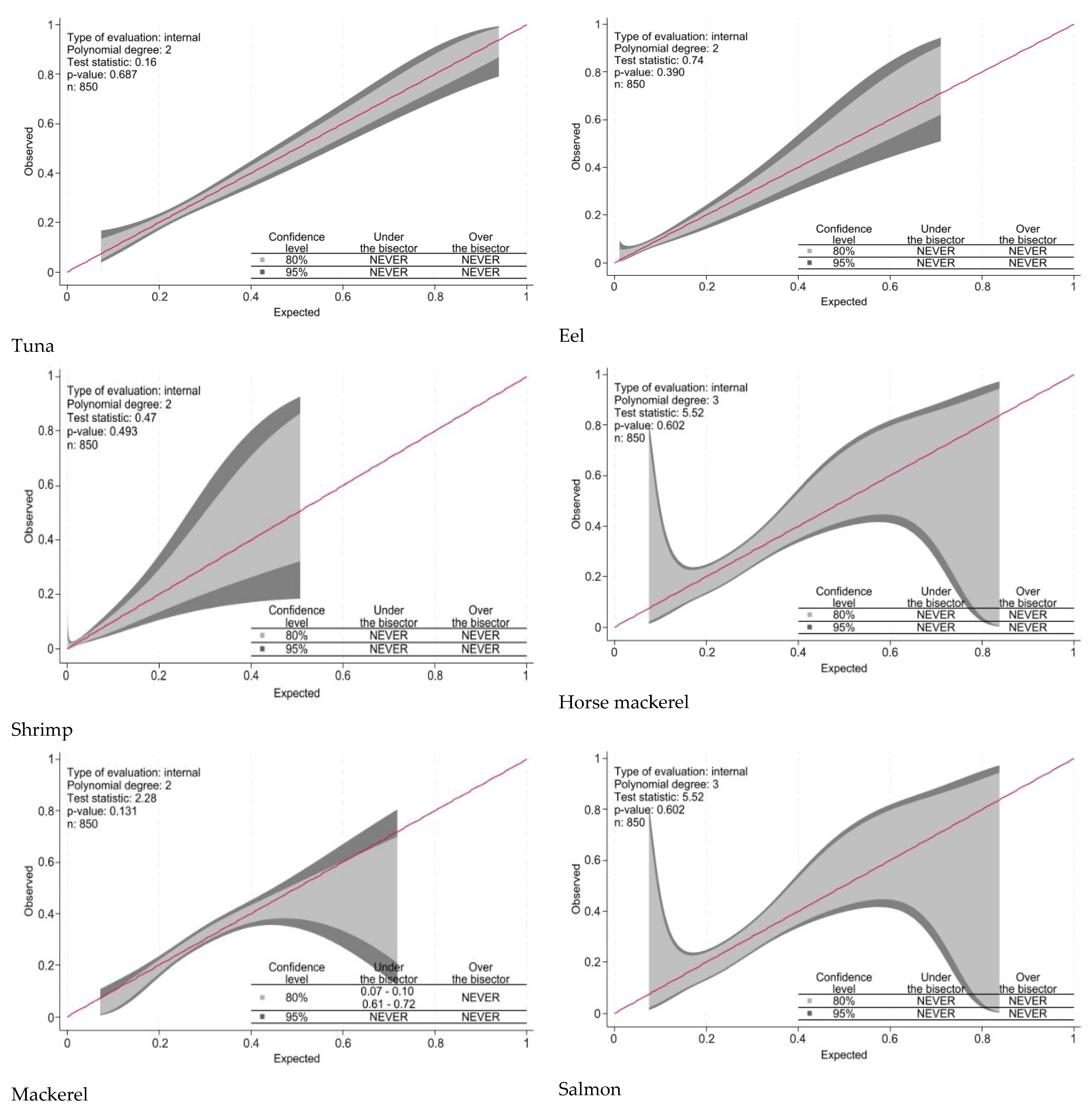

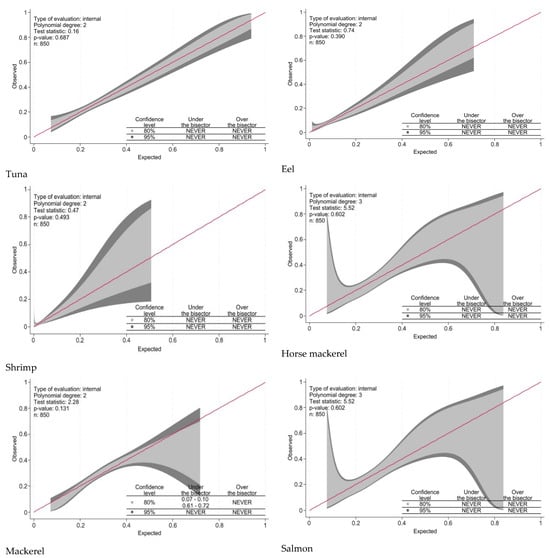

Finally, to test the goodness of fit of the binary logit models presented in Table 8, we conducted a calibration test developed by Nattino et al. [25]. The results of the calibration test in Figure 1 show that the null hypothesis of good calibration was not rejected at the 5% significance level, suggesting that all the linear logit models applied to the different types of fish were robust.

Figure 1.

Calibration test for internal validation.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic caused shockwaves in the food market, and the seafood market was no exception. Particularly, shutdowns and restrictions on restaurant operating hours had a detrimental impact on food consumed outside the home. The current study also detected traces of the influence of pandemic-related restrictions on human mobility on seafood consumption.

First, our findings indicated that an increase in individuals’ consumption of seafood for take-out purposes positively affected the frequency of seafood consumption during the pandemic. This result contrasts with that of Engle et al. [11], who observed a decrease in the frequency of take-out orders for seafood among US consumers during the pandemic. They noted that the decline was attributed to concerns regarding the quality, freshness, and safety of consuming seafood through take-out services. Given the widespread practice of purchasing sashimi (sliced raw fish) and sushi in Japan, ordering take-out seafood is more common and frequent compared to this practice in the US. Consequently, we conjecture that concerns regarding the quality or freshness of seafood for takeout did not significantly affect the consumption of take-out food in Japan. Another reason for the gap is that the Japan’s stay-at-home policy was a voluntary request made by the government, unlike the legally binding lockdowns implemented in other countries. Thus, it is suggested that this policy did not disrupt the food distribution system in Japan [26].

Second, the study confirmed that increased stay-at-home hours during the pandemic resulted in a higher frequency of popular seafood consumption. This finding is consistent with that of de la Iglesia et al. [12], who showed an overall increase in seafood consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Since popular seafood is more regularly consumed at home, this result indicates a shift in consumption from high-end seafood enjoyed outside the home to popular seafood being consumed at home due to more people remaining in their homes during the pandemic.

Finally, this study made it evident that as more people directed their spending towards dining at home, the frequency of consuming high-end seafood declined. This suggests that as fewer people dined at restaurants due to confinement measures, more people allocated their money towards home dining. This result is aligned with that of Aruga et al. [10], in which increased stay-at-home hours caused a sharp decline in luxury seafood prices.

Overall, the study results indicate that when human mobility is restricted during a pandemic, there is a shift in consumption from seafood prepared in restaurants to seafood consumed at home. Therefore, policies should be implemented to support suppliers, restaurants, and retailers dealing with high-end seafood, as they are likely to face economic challenges due to stagnant consumption. Additionally, policies should aim to help stabilize the seafood market and support the development of infrastructure to offer more takeout options for seafood. This is crucial, as there is likely to be an increase in seafood consumed at home during pandemics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A. and H.W.; methodology, K.A.; software, K.A.; validation, K.A.; formal analysis, K.A.; investigation, K.A. and H.W.; resources, K.A.; data curation, K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.; writing—review and editing, K.A. and H.W.; visualization, K.A.; supervision, K.A.; project administration, K.A. and H.W.; funding acquisition, K.A. and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [grant number JP 21H04738].

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Elleby, C.; Domínguez, I.P.; Adenauer, M.; Genovese, G. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Global Agricultural Markets. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, H.; Changotra, R.; Rajput, P.; Gautam, S.; Gollakota, A.R.; Arora, A.S. A Shock Like No Other: Coronavirus Rattles Commodity Markets. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 23, 6564–6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arita, S.; Grant, J.; Sydow, S.; Beckman, J. Has Global Agricultural Trade Been Resilient under Coronavirus (COVID-19)? Findings from an Econometric Assessment of 2020. Food Policy 2022, 107, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aruga, K.; Islam, M.M.; Jannat, A. Effects of the State of Emergency during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tokyo Vegetable Markets. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Sacchi, G.; Carfora, V. Resilience Effects in Food Consumption Behaviour at the Time of COVID-19: Perspectives from Italy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timpanaro, G.; Cascone, G. Food Consumption and the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Sustainability in Purchasing Choices. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, E.R.; Froehlich, H.E.; Gephart, J.A.; Cottrell, R.S.; Branch, T.A.; Agrawal, B.R.; Baum, J.K. Early Effects of COVID-19 on US Fisheries and Seafood Consumption. Fish Fish. 2021, 22, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amos, H.; Giron-Nava, A.; Nguyen, T.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Colleter, M.; Gonzalez-Espinosa, P.C.; Swartz, W. Collapse and Recovery of Seafood Wholesale Prices in Time of COVID-19. Fish Fish. 2022, 23, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aruga, K. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tokyo Wholesale Tuna Market. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Aruga, K.; Islam, M.M.; Jannat, A. The Impacts of COVID-19 on Seafood Prices in Japan: A Comparison between Cheap and Luxury Products. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engle, A.; Senten, J.; Kumar, G.; Dey, M. Pre- and Post-Pandemic Seafood Purchasing Behavior in the U.S. Aquaculture 2023, 571, 739491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Iglesia, R.; García-González, A.; Achón, M.; Varela-Moreiras, G.; Aperte, A.E. Fish, Seafood, and Fish Products Purchasing Habits in the Spanish Population during COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umino, N.; Matsui, T. Analysis of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sales of Marine Products in the Direct-to-Consumer EC. J. Reg. Fish. Econ. 2023, 63, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, N.; Maruyama, Y.; Wakamatsu, H. Consumer Food Demand in Japan before and after the beginning of COVID-19: AIDS Analysis Using Home Scan Data. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 920722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loew, C. Japan’s Latest Whitepaper Highlights Another Drop in Seafood Consumption. 2022. Available online: https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/japan-s-latest-whitepaper-highlights-another-drop-in-seafood-consumption (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- The Toyosu Shijou. Fisheries Market. Available online: https://www.toyosu-market.or.jp/en/fisheries-market (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Narita, M. Umi ni Kakomareta Nihon no Gyokakuryo (Fish Catch of a Country Surrounded by Sea, Japan). Available online: https://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/j/kikaku/wpaper/R4/attach/pdf/230602-6.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). Shoku Iku ni Kansuru Ishikichousahoukokusho (Nutrition Education Awareness Survey Report); MAFF: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syokuiku/ishiki/r03/pdf_index.html (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Gender Equity Bureau Cabinet Office (GEBCO). Kajotou to Shigoto no Balansu ni Kansuru Chousahoukokusho (Report on the Balance Between Household Duties and Work); GEBCO: Tokyo, Japan, 2020. Available online: https://www.gender.go.jp/research/kenkyu/pdf/balance_research_202003/01.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Gerritsen, S.; Egli, V.; Roy, R.; Haszard, J.; De Backer, C.; Teunissen, L.; Cuykx, I.; Decorte, P.; Pabian, S.; Van Royen, K.; et al. Seven Weeks of Home-cooked Meals: Changes to New Zealanders’ Grocery Shopping, Cooking and Eating during the COVID-19 Lockdown. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2021, 51 (Suppl. S1), S4–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibfar, A.; Gulhare, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Costin, A. Analysis and Modeling of Changes in Online Shopping Behavior Due to COVID-19 Pandemic: A Florida Case Study. Transp. Policy 2022, 126, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, T.; Li, Y. Analyzing the Impact of COVID-19 on Consumption Behaviors through Recession and Recovery Patterns. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). Wagakuni no Suisanbutu no Jukyu Shouhi wo Meguru Ugoki (Trends in the Supply-and-Demand and Consumption of Fish and Fishery Products in Japan); MAFF: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. Available online: https://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/j/kikaku/wpaper/r03_h/trend/1/t1_1.html (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Inoue, E. Koronaka de Akka Sita Jyosei no Koyou Shotokukankyo (Employment and Income Environment for Women Worsened under the COVID-19 Pandemic). JRI Rev. 2021, 7, 50–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nattino, G.; Finazzi, S.; Bertolini, G. A New Test and Graphical Tool to Assess the Goodness of Fit of Logistic Regression Models. Stat. Med. 2016, 35, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, M.; Cato, S.; Iida, T.; Ishida, K.; Ito, A.; McElwain, K.M. Variations in Early-Stage Responses to Pandemics: Survey Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan. Econ. Disasters Clim. Chang. 2022, 6, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).