Abstract

Background/Objectives: Sleep is essential to human health, playing a vital role in physical and mental well-being. Sleep disorders can lead to significant health complications, such as cardiovascular problems, diabetes, obesity, and depression. In Brazil, plants such as passionflower (Passiflora spp.), chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) and mulungu (Erythrina spp.) are widely used in folk medicine for their sleep-promoting properties. This article reviews the existing literature on the sleep-promoting effects of these plants, focusing on the Brazilian context and popular knowledge of their use. Methods: An integrative literature review was conducted, including scientific articles in English and Portuguese from PubMed, Scielo and Google Scholar databases. Ethnobotanical studies documenting the traditional use of these plants in Brazil and clinical and preclinical research on their sleep-promoting effects were included. Results: The juice and infusion of the leaves and fruits of passionflower are mainly used to treat anxiety and insomnia, chamomile flower tea is used for its sedative effects, and mulungu bark decoctions are used for their sedative and anxiolytic properties. These popular uses are supported by scientific studies demonstrating the efficacy of these plants in treating insomnia, anxiety, and stress. Conclusions: The recognition of traditional knowledge and the inclusion of these plants in RENISUS highlights their importance for public health in Brazil. However, more rigorous clinical trials are needed to confirm their efficacy and safety and ensure their safe integration into modern medicine.

1. Introduction

Quality sleep is essential for human health and plays a crucial role in both physical and mental well-being. Insomnia can lead to cognitive issues, including difficulty concentrating, reduced learning ability, and significant mood swings. Sleep issues are common and can negatively impact overall health, increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and depression [1]. During sleep, the brain undergoes a ’cleansing’ process. Metabolic waste accumulated during wakefulness is cleared, promoting neural health and overall well-being [2]. Sleep also promotes memory consolidation. This process allows new information to be integrated into long-term memory [3].

Medicinal plants have been used by different cultures throughout history to treat various ailments, including sleep disorders [4]. In Brazil, passionflower (Passiflora spp.), chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.), and mulungu (Erythrina spp.) are widely recognised for their medicinal properties. Among their many health benefits, their calming, anxiolytic, and anti-inflammatory properties stand out, along with their ability to promote sleep and alleviate insomnia. In addition, these plants have great cultural and historical significance in Brazil and have been traditionally used in folk medicine [5,6,7,8,9,10].

Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla L., and Erythrina mulungu Mart. are listed in RENISUS (the National List of Medicinal Plants of Interest to the SUS) due to their potential to generate products relevant to the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS). Their inclusion underscores their significance for public health and reinforces the need for the safe and effective use of traditional medicinal plants in integrative and complementary health practices [11].

Passiflora spp. (Passifloraceae), commonly known as passionflower or passion fruit, is native to tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas [12]. Passionflower has a long history of use in traditional Brazilian medicine and is valued for its calming and sedative properties. Ethnobotanical studies show that the leaves and flowers of this plant are often used to prepare teas and extracts for the treatment of insomnia, anxiety, and other nervous disorders [13]. Research by Dhawan and colleagues [14] highlights flavonoids as the main bioactive compounds responsible for these effects, in addition to their proven antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [15].

Matricaria chamomilla L. (Asteraceae) is widely used in traditional medicine around the world, including in Brazil. Chamomile is known for its anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, and calming properties [16]. Ethnobotanical studies suggest its use in the relief of gastrointestinal symptoms such as colic and indigestion, and in the treatment of anxiety and insomnia [17]. Sah and colleagues [18] identified the presence of apigenin and other flavonoids as key compounds responsible for the therapeutic effects of chamomile.

Erythrina mulungu Mart. (Fabaceae) is a native Brazilian tree traditionally used for its anxiolytic and sedative properties [19]. Rambo and colleagues [20] identified Erythrina-type alkaloids that contribute to the pharmacological properties of the plant.

This study aimed to review the literature on the sleep-promoting effects of passionflower, chamomile, and mulungu, with a focus on studies conducted in Brazil and an emphasis on traditional knowledge of their use. In addition, this work aims to valorise the richness of Brazilian traditional knowledge and ancestral practices in health care and well-being.

2. Results

The literature search yielded 124 relevant articles. After the initial selection and exclusion of ineligible studies, 29 articles were included in the review, all classified as ethnobotanical studies. These articles provided a comprehensive overview of the sleep-promoting effects of the plants studied. The results for each species are presented in the following tables: Table 1 summarises studies on passionflower, Table 2 on chamomile, and Table 3 on mulungu.

Table 1.

Sleep-inducing properties of passionflower (Passiflora spp.) according to traditional use in Brazil.

Table 1.

Sleep-inducing properties of passionflower (Passiflora spp.) according to traditional use in Brazil.

| Species | Popular Name in Brazil | Effect | Plant Part | Preparation Method | Study Area * | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passiflora coccinea Aubl. | Maracujá | Sedative | Leaves, fruit pulp | Infusion, water maceration, juice | Eldorado, Jacupiranga and Sete Barras (SP) | [21] |

| Passiflora alata Curtis Passiflora edulis Sims | Maracujá, maracujá-do-mato, maracujá-de-casa, maracujina | Soothing, “for nerves”, “tranquilliser” | Leaves, fruits | Jam, fruit, juice | Porto Alegre (RS) | [22] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Maracujá | Sedative | Fruit pulp | Juice | Northeast | [23] |

| Passiflora sp. Passiflora caerulea L. | Maracujá | Treats nervousness, anxiety and insomnia; sedation | Nm ** | Nm | Pelotas, Morro Redondo, Canguçu, Turuçu, Arroio do Padre (RS) | [24] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims Passiflora cincinnata Mast. | Maracujá, maracujá-do-mato | Soothing | Leaves | Decoction | Aiuaba (CE) | [25] |

| Passiflora edulis | Maracujá | Soothing | Nm | Nm | Durandé (MG) | [26] |

| Passiflora incarnata L. | Maracujá | Soothing, anti-fatigue | Fruits | Juice | Queimadas (PB) | [27] |

| Passiflora edulis Passiflora sp. | Maracujá, maracujá-açu | Soothing | Leaves, fruits | Tea, “lambedor” | Camocim de São Félix (PE) | [28] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Maracujá | Soothing | Fruit peel | Powder | Picuí (PB) | [29] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Maracujá | Sleep aid; treats distress and anxiety | Fruit peel, leaves, flower | Nm | Porteirinha (MG) | [30] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Maracujá | Soothing | Leaves | Infusion | São Gabriel (RS) | [31] |

| Passiflora alata Curtis | Maracujá | Soothing | Nm | Nm | Vale do Juruena region (MT) | [32] |

| Passiflora sp. | Maracujá do mato | Soothing; resolves nervousness | Leaves, fruits, roots | Infusion | Exu (PE) | [33] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Maracujá | Soothing | Nm | Powder, juice | Cuité (PB) | [34] |

| Passiflora sp. | Maracujá do mato | Soothing | Leaves | Decoction, juice | Antonina do Norte (CE) | [35] |

| Passiflora edulis | Maracujá | Resolves nervousness | Leaves | Infusion, decoction | Vitória da Conquista (BA) | [36] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Maracujá | Treats anxiety and insomnia | Flower, leaves | Juice, infusion | Cuitegi (PB) | [37] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims. | Maracujá | “To relieve nervousness” | Fruits, leaves | Juice, infusion | Northeast region (17 cities) | [38] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims. | Maracujá | Soothing, treats insomnia | Leaves, fruits | Decoction, juice | Maceió (AL) | [39] |

| Passiflora cincinnata | Maracujá do mato | Stress relief, treats anxiety and insomnia | Leaves | Nm | Juazeiro do Norte (CE) | [40] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Maracujá | Soothing to sleep | Leaves | Tea | São João das Missões (MG) | [41] |

* Abbreviations in brackets refer to Brazilian states: SP—São Paulo; RS—Rio Grande do Sul; CE—Ceará; MG—Minas Gerais; PB—Paraíba; PE—Pernambuco; MT—Mato Grosso; BA—Bahia; AL—Alagoas. ** Nm = not mentioned in the original article.

Table 2.

Sleep-inducing properties of chamomile according to traditional use in Brazil (Matricaria chamomilla L. is the accepted species name in World Flora Online).

Table 2.

Sleep-inducing properties of chamomile according to traditional use in Brazil (Matricaria chamomilla L. is the accepted species name in World Flora Online).

| Species | Popular Name in Brazil | Effect | Plant Part | Preparation Method | Study Area * | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matricaria recutita | Camomila | Sedative; sedative for children | Leaves, seeds | Internal use | Eldorado, Jacupiranga and Sete Barras (SP) | [21] |

| Matricaria chamomilla | Camomila | Soothing | Nm ** | Nm | Marília (SP) | [42] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Camomila | Resolves nervousness | Flowers | Cooking | Juazeiro (BA) | [43] |

| Chamomilla recutita (L.) | Camomila | Soothing | Leaves, seeds | Decoction | Aiuaba (CE) | [25] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Camomila | Soothing | Nm | Nm | Durandé (MG) | [26] |

| Chamomilla recutita L. | Camomila | Soothing | Flowers | Infusion | Queimadas (PB) | [27] |

| Chamomilla recutita | Camomila | Soothing | Leaves, flowers | Tea | Camocim de São Félix (PE) | [28] |

| Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert | Camomila | Soothing, stress relief | Flowers | Tea, bath | Picuí (PB) | [29] |

| Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert | Camomila | Resolves nervousness | Flowers | Tea | Nova Palmeira, Frei Martinho (PB) | [29] |

| Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert | Camomila | Tranquiliser, sleep aid | Leaves, flowers | Nm | Porteirinha (MG) | [30] |

| Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert | Camomila | Soothing | Flowers | Tea | Puxinanã (PB) | [44] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Camomila | Soothing | Flowers | Infusion | São Gabriel (RS) | [31] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Camomila | Soothing | Nm | Nm | Vale do Juruena region (MT) | [32] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Camomila | Soothing, treats insomnia | Nm | Infusion | Cuité (PB) | [34] |

| Matricaria chamomila L. | Camomila | Resolves nervousness, soothing, treats insomnia | Flowers, seeds, leaves | Infusion | Antonina do Norte (CE) | [35] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Camomila | Tranquiliser | Flowers | Infusion | Vitória da Conquista (BA) | [36] |

| Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert | Camomila | Anti-anxiety | Flowers | Decoction | Cuitegi (PB) | [37] |

| Chamomilla recutita L. | Camomila | Soothing | Flowers | Tea | Barra de Santa Rosa, Cuité, Nova Floresta, Baraúna, Picuí e Jaçanã (RN) | [45] |

| Matricaria recutita L. | Camomila | Soothing | Flowers | Infusion, decoction | Maceió (AL) | [39] |

| Matricaria chamomilla (L.) Rauschert | Camomila | Resolves nervousness; tranquiliser | Flowers | Decoction, infusion | Araçagi (PB) | [46] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Camomila | Treats insomnia, stress and anxiety; soothing | Flowers | Infusion | Juazeiro do Norte (CE) | [40] |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Camomila | Soothing | Flowers | Nm | Brejo da Madre de Deus (PE) | [47] |

* Abbreviations in brackets refer to Brazilian states: SP—São Paulo; BA—Bahia; CE—Ceará; MG—Minas Gerais; PB—Paraíba; RS—Rio Grande do Sul; MT—Mato Grosso; RN—Rio Grande do Norte; AL—Alagoas; PE—Pernambuco. ** Nm = not mentioned in the original article.

Table 3.

Sleep-inducing properties of mulungu (Erythrina spp.) according to traditional use in Brazil.

Table 3.

Sleep-inducing properties of mulungu (Erythrina spp.) according to traditional use in Brazil.

| Species | Popular Name in Brazil | Effect | Plant Part | Preparation Method | Study Area * | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Treats insomnia | Bark | Infusion or decoction of a handful in one litre of water | Northeast | [23] |

| Erythrina mulungu Mart. Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Calming, treats insomnia and anxiety | Bark, flower, leaf, fruit, seeds | Nm ** | Northeast | [48] |

| Erythrina mulungu Mart. Ex. Benth | Mulungu | Treats nervousness and insomnia | Leaves, bark | Boiling, infusion, steeping | Petrolina (PE), Juazeiro and Sento-Sé (BA) | [43] |

| Erythrina speciosa | Mulungu | Treats nervousness, anguish, insomnia | Nm | Nm | Pelotas, Morro Redondo, Canguçu, Turuçu and Arroio do Padre (RS) | [24] |

| Erythrina speciosa Andrews | Pau-cebola, pau-sabão, mulungu | Calming | Nm | Nm | Durandé (MG) | [26] |

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Treats insomnia | Bark | Maceration | Queimadas (PB) | [27] |

| Erythrina mulungu | Mulungu | Calming | Leaf and bark | Tea | Camocim de São Félix (PE) | [28] |

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Treats stress and insomnia | Bark | Tea, tincture, traditional herbal syrup preparation (“lambedor”) | Nova Palmeira (PB) | [29] |

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Treats insomnia | Bark | Tea | Frei Martinho, PB | [29] |

| Erythrina mulungu Mart. ex Benth. | Mulungu | Sedative; treats depression | Leaf, inner bark, seed | Nm | Porteirinha (MG) | [30] |

| Erythrina velutina Willd | Mulungu | Calming | Bark and seed | Tea from the bark, bark soaked in water, crushed seed | Puxinanã (PB) | [44] |

| Erythrina verna Vell. | Corticeira, mulungu | Treats nervous system problems | Bark | Decoction and tincture | São Pedro do Iguaçu (PR) | [49] |

| Erythrina verna Vell. | Mulungu | Tranquilizer, resolves nervous crisis, treats depression, stress, and insomnia | Bark and leaves | Infusion, maceration | Norte Araguaia microregion (MT) | [50] |

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Treats insomnia | Bark | Decoction | Cuitegi (PB) | [37] |

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Treats sleep disorders | Bark (outer and inner), seeds | Infusion, decoction, fresh or powdered | Northeast region (17 cities) | [38] |

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Treats nervousness, antidepressant | Bark | Traditional herbal preparations (“garrafadas”) | Barra de Santa Rosa, Cuité, Nova Floresta, Baraúna, Picuí and Jaçanã (RN) | [45] |

| Erythrina velutina Vell. | Mulungu | Treats insomnia, anxiety, and depression | Bark | Infusion | Juazeiro do Norte (CE) | [40] |

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Mulungu | Calming | Bark | Nm | Brejo da Madre de Deus (PE) | [47] |

| Erythrina verna Vell. | Casca-de-mulungu | Treats insomnia | Bark | Tea | São João das Missões (MG) | [41] |

* Abbreviations in brackets refer to Brazilian states: PE—Pernambuco; BA—Bahia; RS—Rio Grande do Sul; MG—Minas Gerais; PB—Paraíba; PR—Paraná; MT—Mato Grosso; RN—Rio Grande do Norte; CE—Ceará. ** Nm = not mentioned in the original article.

3. Discussion

The practice of using medicinal plants is deeply rooted in the cultures and traditions of different regions of Brazil [51]. The diversity of Brazilian flora, exemplified in this study by passionflower, chamomile, and mulungu, contributes to the health and well-being of the population.

The reviewed ethnobotanical studies demonstrated a wide range of sleep-promoting effects associated with the traditional use of Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla, and Erythrina spp. in Brazil. The most reported benefits include treating insomnia, reducing anxiety, and relieving stress. In addition, these plants are often described as calming and sedative, contributing to relaxation and improved sleep quality. Other relevant effects include the treatment of nervous system disorders, as well as their role as tranquilisers and sleep aids. Some studies also highlight the calming effects of these plants, particularly in children. All these effects are related to good sleep health [1] and have been classified in this article as ’sleep-promoting effects’.

Although Passiflora spp. and Erythrina spp. comprise multiple species with different scientific names, the results show species that are popularly known in Brazil as passionflower (maracujá) and mulungu, respectively. This diversity in nomenclature justifies the inclusion of various species in the analysis, such as Passiflora edulis Sims, Passiflora coccinea Aubl., Passiflora alata Curtis, Passiflora caerulea L., Passiflora cincinnata Mast., Passiflora incarnata L., Erythrina velutina Willd., Erythrina mulungu Mart. ex Benth., Erythrina speciosa Andrews, and Erythrina verna Vell. Ethnobotanical studies reviewed here indicate that all these species have sleep-promotion properties. In contrast, despite historical variations in its nomenclature and other botanical names considered synonyms, Matricaria chamomilla remains the only chamomile species taken into account [52].

To discuss the effects of these plants on human health, the therapeutic effects reported by the scientific literature were analysed. The findings were then compared with the results of the ethnobotanical studies presented in this review.

Studies suggest that passionflower is used to treat anxiety and insomnia, possibly due to the presence of flavonoids and alkaloids such as vitexin and chrysin, which have anxiolytic and sedative effects [14,53]. Movafegh and colleagues [54] confirmed these effects in a clinical trial in which oral administration of Passiflora incarnata in tablet form (500 mg, Passipy™ IranDarouk) significantly reduced preoperative anxiety in patients compared with placebo. The tablets were administered 90 min before surgery and led to a significant reduction in anxiety levels without inducing sedation. Anxiety scores measured using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) were significantly lower in the Passiflora group than in the control group (p < 0.001). Initial scores were 4.6 ± 1.7 in the Passiflora group and 5.1 ± 2 in the control group. After 90 min, anxiety scores decreased to 3.88 in the control group and 0.97 in the Passiflora group [54].

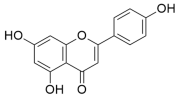

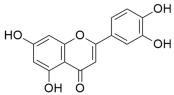

Chamomile is recognised for its calming and anti-inflammatory properties and has been shown to be effective in treating insomnia and anxiety [16,17]. Zick and colleagues [55] tested a standardised dry hydroethanolic extract of Matricaria recutita flowers (270 mg twice daily) and observed a reduction in sleep latency of about 16 min. In addition, it reduced the number of nighttime awakenings by 0.8 in patients with chronic insomnia. Although the results were moderate, they suggest that chamomile may have a beneficial effect on sleep quality [55]. The flavonoid apigenin, found in chamomile, binds to benzodiazepine receptors, specific proteins that modulate the activity of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter. This interaction produces sedative and anxiolytic effects, as indicated by Sepp and colleagues [56].

In addition, significant concentrations of luteolin and its glycosylated derivatives were identified and quantified in the hydroethanolic extract of Matricaria chamomilla flowers using UPLC-MS/MS [55]. Luteolin has well-documented anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties. These properties may contribute to the sedative and analgesic effects of chamomile [16,18,56].

Recent clinical trials have investigated the effectiveness of chamomile extract in improving sleep quality and reducing anxiety symptoms. A randomised, controlled trial by Adib-Hajbaghery and Mousavi [57] evaluated the effects of a spray-dried hydroethanolic Matricaria recutita extract on sleep quality in older adults. The treatment group received 200 mg of chamomile extract twice daily for 28 days, while the control group received a placebo. Both groups had poor sleep quality at baseline, as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), but the differences were not significant. However, after the intervention, the treated group improved their sleep quality compared to the placebo group (p < 0.05). This supports the potential of chamomile as a natural sleep aid [57].

In addition, a long-term randomised clinical trial by Mao and colleagues [58] investigated the effects of chamomile extract on generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). In this 38-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, participants initially received 1500 mg of pharmaceutical-grade chamomile extract daily for 12 weeks. The hydroethanolic extract of Matricaria chamomilla L. flowers has been standardised to provide 6 mg of apigenin-7-glucosides (Api-7Glc) per 500 mg capsule. Those who had a positive response were then randomised to either continue with chamomile therapy for a further 26 weeks or to switch to a placebo. The chamomile group maintained significantly lower levels of GAD symptoms than the placebo group (p = 0.0032), indicating a sustained anxiolytic effect. Although the time to recurrence of anxiety symptoms was longer in the chamomile group (11.4 ± 8.4 weeks) than in the placebo group (6.3 ± 3.9 weeks), this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.16). Chamomile treatment was well tolerated, with no serious adverse effects reported, and was even associated with a small reduction in blood pressure [58].

These findings support chamomile as a safe and effective alternative for improving sleep quality and reducing anxiety symptoms, particularly in older adults and those with GAD. However, further large-scale clinical trials are needed to confirm the therapeutic potential of chamomile.

Mulungu is traditionally used in Brazil for its sedative and anxiolytic properties [19,38]. Rambo and colleagues [20] have identified alkaloids, such as erysotrine and erythravine, that are thought to be responsible for these effects. Ribeiro and colleagues [59] demonstrated that Erythrina mulungu has anxiolytic potential comparable to diazepam in animal models. A hydroalcoholic extract of mulungu inflorescences was administered orally at acute doses of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg, and chronic doses of 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg. Mulungu treatment significantly reduced avoidance latencies in the T-maze test, without affecting escape measures, similar to diazepam and without impairing the animals’ motor activity.

Although these findings support the anxiolytic potential of Erythrina spp., clinical trials evaluating its efficacy in humans have been lacking until recently. Recent clinical trials have sought to evaluate the efficacy of Erythrina mulungu in anxiety management in humans. A randomised, placebo-controlled, triple-blind clinical trial by Cunha and colleagues [60] compared the effects of Erythrina mulungu (500 mg, Matusa® formulation), Passiflora incarnata (500 mg), and midazolam (15 mg) in patients undergoing third molar extraction. Anxiety levels were assessed using questionnaires and physiological parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. Passiflora incarnata showed anxiolytic effects comparable to midazolam. However, Erythrina mulungu did not differ significantly from the placebo, suggesting that its efficacy may be limited in acute anxiety scenarios, such as preoperative dental anxiety [60].

Erythrina mulungu showed an anxiolytic effect in patients undergoing bilateral third molar extraction in a randomised, double-blind, crossover study by Silveira-Souto and colleagues [61]. A dose of 500 mg of Erythrina mulungu (Matusa® formulation) was administered one hour before surgery. Patients showed a statistically significant preference for Erythrina mulungu over placebo, particularly among those with higher baseline anxiety levels. No significant differences in physiological parameters (blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation) were observed between the groups, despite subjective reports of reduced anxiety [61].

These findings highlight the complexity of the anxiolytic potential of Erythrina mulungu. While in vivo studies suggest potent sedative and anxiolytic effects, clinical evidence in humans remains inconclusive. This may be influenced by differences in study design, dosage, and the specific anxiety context being assessed. Further research, particularly large-scale clinical trials, is needed to determine the full therapeutic potential of Erythrina mulungu and its possible applications in modern medicine.

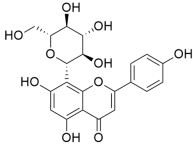

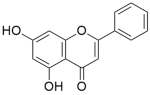

The key bioactive compounds of these medicinal plants, including alkaloids and flavonoids, are listed in Table 4. These compounds are likely to contribute to the anxiolytic and sedative effects reported in both traditional and clinical studies.

Table 4.

Key bioactive compounds in Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla, and Erythrina spp. and their biological properties.

Table 4.

Key bioactive compounds in Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla, and Erythrina spp. and their biological properties.

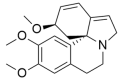

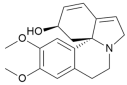

| Compound | Source Plant | Class | Molecular Structure * | Biological Properties |

| Vitexin | Passiflora spp. | Flavonoid |  | Anti-inflammatory [62] Antidiabetic [63] Antitumor [64] Neuroprotective [65] |

| Chrysin | Passiflora spp. | Flavonoid |  | Anti-inflammatory [66] Antitumor [67] Hepatoprotective [68] Neuroprotective [69] |

| Apigenin | Matricaria chamomilla | Flavonoid |  | Anti-inflammatory [70] Cardioprotective [71] Neuroprotective [72] Anxiolytic [73] |

| Luteolin | Matricaria chamomilla | Flavonoid |  | Anti-inflammatory [74] Antihypertensive [75] Anxiolytic [76] Antidepressant [76] |

| Erysotrine | Erythrina spp. | Alkaloid |  | Anxiolytic [77] Anticonvulsant [77] |

| Erythravine | Erythrina spp. | Alkaloid |  | Anxiolytic [78,79] |

* Molecular structures were drawn using ChemDraw® Ultra 12.0.2 (CambridgeSoft®).

The correlation between the bioactive compounds identified in Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla, and Erythrina spp. and their documented pharmacological properties highlights their therapeutic relevance. Although their anxiolytic and sedative effects have long been recognised in traditional medicine, scientific validation remains inconsistent. Clinical evidence on Passiflora spp. and Matricaria chamomilla is relatively robust, whereas studies on Erythrina spp., particularly Erythrina mulungu, are limited and somewhat contradictory. Preclinical research suggests the anxiolytic potential of Erythrina-type alkaloids. However, the lack of standardised methodologies and the absence of large-scale clinical trials hinder a conclusive understanding of their efficacy [20]. Future research should aim to fill these gaps and ensure that the therapeutic applications of these plants are supported by rigorous scientific evaluation and optimised for clinical use.

In Brazil, Passiflora spp. is widely known for its use in treating anxiety and improving sleep, often consumed as a juice, infusion, or decoction, primarily derived from its leaves and fruits [22,23,31]. Similarly, chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) is well recognised for its calming effects, and is commonly prepared as an infusion of its flowers [31,40]. Erythrina mulungu, highly valued in traditional medicine, is predominantly used in northeastern Brazil, where its bark is prepared as a decoction for its sedative properties [40,43]. The Brazilian Pharmacopoeia provides official guidelines for the extraction of these plants. According to its monographs, different species of Passiflora are officially recognised for their medicinal properties: Passiflora alata is prepared as an infusion of the leaves in water (1:50 w/v) for its anxiolytic and sedative effects; Passiflora edulis is also used in folk medicine as a sedative; while Passiflora incarnata is used for anxiety and insomnia, typically prepared as an infusion of its aerial parts [80,81]. Matricaria chamomilla is usually consumed as an infusion of its flowers (0.5–4 g per 150 mL of water) for its calming effects [82]. Erythrina mulungu is traditionally used as a decoction of the bark (0.5 g per 150 mL of water) for its sedative properties [82].

These findings highlight the cultural importance of these plants in Brazil. The traditional use of passionflower, chamomile, and mulungu in folk medicine reflects a deep appreciation of the country’s natural resources for promoting human health. Preserving this knowledge is essential to maintaining Brazil’s cultural identity and promoting alternative therapeutic options in medicine. In addition, the inclusion of Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla L., and Erythrina mulungu in RENISUS [11] reinforces the therapeutic potential and cultural significance of these plants in Brazil. These species provide complementary alternatives for the treatment of sleep disorders and anxiety, contributing to overall public health. However, more rigorous clinical trials are required to ensure the safety and efficacy of these treatments in humans. Further research on these plants could contribute significantly to promoting health and well-being in Brazil and globally.

In addition, the wide geographical distribution of the ethnobotanical studies analysed here is highly relevant to this discussion. The fact that studies have been conducted across different regions of Brazil—including the northeast, south, southeast, and midwest—demonstrates the widespread popularity and trust in these medicinal plants among different cultural groups. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of ethnobotanical studies, highlighting both Brazil’s cultural diversity and rich biodiversity.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of ethnobotanical studies conducted in Brazil between 2000 and 2024, including Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla L., and Erythrina spp. Created with MapChart.

The geographical diversity of these plants’ use demonstrates their cultural significance. The alignment between ethnobotanical findings and scientific studies further highlights the importance of recognising and valuing traditional knowledge across diverse cultural and ecological contexts. Each Brazilian region has its own unique practices and adaptations. This diversity enriches the understanding of the use of these plants and highlights traditional wisdom in utilising natural resources for health promotion.

The widespread use of Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla L., and Erythrina spp. for sleep-promoting effects also reinforces the need for public policies that support research and conservation of the biome. Protecting traditional knowledge ensures that its benefits remain widely accessible. This approach not only values Brazilian culture but also contributes to the country’s sustainability and biodiversity.

Herbal medicines containing two of the species studied are already registered with the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA). According to the ANVISA website [83], there are currently 45 registered herbal medicinal products containing Passiflora incarnata. Of these, 39 contain only Passiflora incarnata, while six are formulated in combination with other plant species, such as Valeriana officinalis, Crataegus rhipidophylla, and Salix alba. All these products are registered under the therapeutic class of anxiolytics, supporting the traditional use reports identified in this study.

In contrast, for Matricaria recutita, only one record was found for an anti-inflammatory ointment (Ad-muc®, Biolab Sanus Farmacêutica), with no registered herbal medicinal products specifically indicated for sleep promotion. Also, no registered medicines containing mulungu (Erythrina spp.) were found in the ANVISA database. This may indicate a gap in scientific research and validation, or in the regulatory framework for the official medicinal use of this species.

In addition, many of these herbal products registered with ANVISA are classified as PTFs (from the Portuguese Produtos Tradicionais Fitoterápicos, meaning traditional herbal products), as established by a resolution of the Collegiate Council (RDC No. 26/2014) [84]. This type of registration is based on traditional use, where the safety and efficacy of PTFs are based on the demonstration of their safety and effective use for more than thirty years. This type of registration emphasises the importance of traditional knowledge and its recognition within formal medicine. This is also evident in the National Policy on Integrative and Complementary Practices (PNPIC), which promotes the use of traditional treatments, such as phytotherapy, within the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) [85].

4. Materials and Methods

This article presents an integrative review of the existing literature to investigate the sleep-promoting effects of the popular use of Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla L. and Erythrina spp. in Brazil. The literature search was carried out in June 2024. The databases used were PubMed, Scielo and Google Scholar. The searches were conducted using specific keyword combinations in Portuguese and English to ensure that the results were relevant and specific. Keywords related to plants, location, context, and effects were defined in the search process. The search included the following keywords: species names ‘Passiflora spp.’, ‘Chamomilla recutita’ and ‘Erythrina mulungu’; Brazil” (English) and “Brasil” (Portuguese) were the keywords related to location; ‘ethnobotanical’ (Portuguese) and ‘ethnobotanical’ (English) were the keywords related to the context; and the keywords related to sleep-promoting effects were ‘ansiolítico’, ‘sedativo’, ‘calmante’, ‘insônia’ (Portuguese) and ‘anxiolytic’, ‘sedative’, ‘calming’, ‘insomnia’ (English).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: scientific articles in English and Portuguese; studies investigating the sleep-promoting effects of Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla L. and Erythrina spp., with emphasis on research conducted in the Brazilian context; and ethnobotanical studies documenting the popular use of these plants in Brazil. Papers written in languages other than English or Portuguese, those that did not correlate a sleep-promoting effect with the popular use of these plants in the Brazilian context, and those that were not ethnobotanical in nature, i.e., that did not document the traditional or popular use of the plants, were not included in this study.

During the data extraction process, key information from the selected articles was recorded. This included the plant species mentioned in each study, the popular name reported in Portuguese by interviewees in ethnobotanical studies, the sleep-promoting effects associated with traditional use, the plant parts used, the preparation method, and the study location.

The information was tabulated to facilitate interpretation, and the results were discussed considering the reviewed literature. This approach highlights their contributions to understanding the sleep-promoting effects of these plants in the context of traditional Brazilian medicine.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that Passiflora spp., Matricaria chamomilla L., and Erythrina spp. play significant roles in Brazilian folk medicine and are widely used for their sleep-promoting properties. Both clinical and preclinical trials validate the effects observed in traditional practice, particularly in the treatment of anxiety and sleep disorders.

Preservation and ongoing research into these medicinal plants are essential, not only because of Brazil’s rich biodiversity but also due to their cultural value and therapeutic potential. The inclusion of these plants in RENISUS highlights their importance and the need for further research to confirm their efficacy and safety, ensuring their safe integration into modern medicine.

Future research should focus on robust clinical trials to validate their traditional uses and explore new therapeutic applications, as well as further examine the cultural significance of these plants in various regions of Brazil. The combination of traditional knowledge with modern science can provide effective and innovative solutions to global health challenges, benefiting both Brazilian and global populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.d.O. and P.C.A.; methodology, P.C.A.; validation, D.B.d.O. and C.C.R.; formal analysis, P.C.A.; investigation, P.C.A.; data curation, C.C.R. and P.C.A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.A.; writing—review and editing, P.C.A. and C.C.R.; supervision, D.B.d.O.; project administration, C.C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro (UENF).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Irwin, M.R. Why Sleep Is Important for Health: A Psychoneuroimmunology Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.J.; Liao, Y.; Thiyagarajan, M.; O’Donnell, J.; Christensen, D.J.; Nicholson, C.; Iliff, J.J.; et al. Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain. Science 2013, 342, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekelmann, S.; Born, J. The Memory Function of Sleep. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feizi, F.; Namazi, N.; Rahimi, R.; Ayati, M.H. Medicinal Plants for Management of Insomnia: A Systematic Review of Animal and Human Studies. Galen 2019, 8, e1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.R.; Rodrigues, R.A.; Ramos, A.S.; da Cruz, J.D.; Ferreira, J.L.P.; da Silva, J.R.A.; Amaral, A.C.F. Herbal Medicinal Products from Passiflora for Anxiety: An Unexploited Potential. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 6598434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, M.J.; Barboza, T.J.S.; Vianna, M.G.; Garcia, R.; Mansur, E.; Ignacio, A.C.P.R.; Pacheco, G. A Comparative Study of Phytoconstituents and Antibacterial Activity of in Vitro Derived Materials of Four Passiflora Species. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2018, 90, 2805–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti-Perdigão, P.; Serrano, M.A.R.; Flausino, O.A.; Bolzani, V.S.; Guimarães, M.Z.P.; Castro, N.G. Erythrina mulungu Alkaloids Are Potent Inhibitors of Neuronal Nicotinic Receptor Currents in Mammalian Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrico, L.D.; Angelini, A.; Figueiredo, A.S.; de Sá Eufrasio, B.; Vedolin, E.C.; Noqueli, L.V.; Brasesco, L.A.; Santiago, R.D.D.S.; Yamato, M.A.C.; Cardoso, M.A.P. A study of the use of mint (Mentha x villosa Huds), passion fruit leaf (Passiflora edulis), Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) and Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) teas in the treatment and prevention of anxiety: A bibliographic review. Braz. J. Dev. 2022, 8, 61985–62005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, R.C.M. Evidence of Gastrointestinal Activity of Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L. = Chamomilla recutita L.): An Integrative Review. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Amazonas, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2021. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/biblio-1291766?lang=en (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Santiago, I.F.; Damasceno, H.G.M.C.; Cavelet, L.C. Pharmacological Profile of Erythrina velutina (E. mulungu) in Anxiety Disorder. Rev. Ibero Am. Humanid. Ciênc. Educ. 2022, 8, 1711–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. RENISUS–National List of Medicinal Plants of Interest to SUS. Espécies Vegetais; 2009. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/sus/pdf/marco/ms_relacao_plantas_medicinais_sus_0603.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Zhang, J.; Tao, S.; Hou, G.; Zhao, F.; Meng, Q.; Tan, S. Phytochemistry, Nutritional Composition, Health Benefits and Future Prospects of Passiflora: A Review. Food Chem. 2023, 428, 136825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lim, H.S.; Lee, H.H.; Kim, T.H. Role Identification of Passiflora incarnata Linnaeus: A Mini Review. J. Menopausal. Med. 2017, 23, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhawan, K.; Dhawan, S.; Sharma, A. Passiflora: A Review Update. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 94, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narain, N.; Shanmugam, S.; de Souza Araújo, A.A. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Analgesic, Anti-Inflammatory and Antipyretic Effects of Bioactive Compounds from Passiflora Species. In Medicinal Plants; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 243–274. ISBN 9783030312688. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, R.; Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A.; Kumari, A.; Rathore, S.; Kumar, R.; Singh, S. A Comprehensive Review on Biology, Genetic Improvement, Agro and Process Technology of German Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). Plants 2022, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mihyaoui, A.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Charfi, S.; Candela Castillo, M.E.; Lamarti, A.; Arnao, M.B. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.): A Review of Ethnomedicinal Use, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Uses. Life 2022, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, A.; Naseef, P.P.; Kuruniyan, M.S.; Jain, G.K.; Zakir, F.; Aggarwal, G. A Comprehensive Study of Therapeutic Applications of Chamomile. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, T.L.; Acho, M.A.; Samuel, V.O.; Ohoro, C.R.; Ramulondi, M. Erythrina velutina Willd.: A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319 Pt 2, 117273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambo, D.F.; Biegelmeyer, R.; Toson, N.S.B.; Dresch, R.R.; Moreno, P.R.H.; Henriques, A.T. The Genus Erythrina L.: A Review on Its Alkaloids, Preclinical, and Clinical Studies. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1258–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasi, L.C.; Oliveira, G.P.; Carvalhaes, M.A.; Queiroz-Junior, M.; Tien, O.S.; Kakinami, S.H.; Reis, M.S. Medicinal plants popularly used in the Brazilian Tropical Atlantic Forest. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, G.S.; Mentz, L.A. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used by Residents of the Ponta Grossa Neighborhood, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Iheringia Sér. Bot. 2006, 61, 83–103. Available online: https://isb.emnuvens.com.br/iheringia/article/view/185 (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- de Fátima Agra, M.; de Freitas, P.F.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M. Synopsis of the plants known as medicinal and poisonous in Northeast of Brazil. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2007, 17, 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceolin, T. Conhecimento sobre Plantas Medicinais entre Agricultores de Base Ecológica da Região Sul do Rio Grande do Sul. Master′s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Pelotas, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cartaxo, S.L.; de Almeida Souza, M.M.; de Albuquerque, U.P. Medicinal Plants with Bioprospecting Potential Used in Semi-Arid Northeastern Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 131, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuler, A.C. Ethnobotanical Survey in the Rural Community of São José da Figueira, Durandé, MG, Brazil. Bachelor′s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alegre, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, S.; Alves, R.; Barbosa, J.; Brasileiro, T. Medicinal Plants Used by a Community in the Semi-Arid Region of Paraíba, Northeastern Brazil. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2012, 93, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S. Local Botanical Knowledge of Medicinal Plants in a Rural Community in the Agreste of Paraíba (Northeastern Brazil). Master′s Thesis, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.C. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Rural and Urban Communities of Seridó Paraibano, Northeastern Brazil. Master′s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Patos, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, C.V.; Oliveira, G.L. Medicinal Plants Used in Casa de Ervas Barranco da Esperança e Vida Association (ACEBEV), Porteirinha, MG. Rev. Fitos 2012, 7, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbler, L.; Santos, D.; Rodrigues, E.S.; Santos, N.R.Z. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in the Três de Outubro Neighborhood, São Gabriel, RS, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Biocienc. 2014, 12, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bieski, I.G.; Leonti, M.; Arnason, J.T.; Ferrier, J.; Rapinski, M.; Violante, I.M.P.; Balogun, S.O.; Pereira, J.F.C.A.; Figueiredo, R.C.F.; Silva, D.R.; et al. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants by Population of Valley of Juruena Region, Legal Amazon, Mato Grosso, Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 383–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, M.E.; de Alencar Ulisses, A.V.R.; Ribeiro, D.A.; de Oliveira, L.G.S.; de Macedo, D.G.; de Sousa, F.D.F.S.; de Menezes, I.R.A.; Sampaio, E.V.D.S.B.; de Almeida Souza, M.M. Plant Species as a Therapeutic Resource in Areas of the Savanna in the State of Pernambuco, Northeast Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 171, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, A.M. Utilização de Plantas Medicinais pela População de Cuité-PB na Atenção Primária à Saúde. Bachelor’s Thesis, Centro de Educação e Saúde, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Cuité, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, F.F.S. Medicinal Plants of the Caatinga in Urban and Rural Areas of the Municipality of Antonina do Norte, CE. Master′s Thesis, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Crato, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marisco, G.; Silva, T.S.S.; Assun, R.; Brendel, M.; Pungartnik, C. The Use of Herbal Medicine in a Rural Community in Vitoria da Conquista, Bahia, Brazil: An Indication for Pharmacological Studies. Int. J. Complement. Alt. Med. 2017, 7, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Silva, S. Conhecimento Botânico Local de Plantas Medicinais em uma Comunidade Rural no Agreste da Paraíba (Nordeste do Brasil). Master’s Thesis, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente. Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, K.D.N.; Guarniz, W.A.S.; Sá, K.M.; Oliveira, J.T.A.; Abreu, I.C.; Santos, J.P.; Matos, F.J.A. Medicinal Plants of the Caatinga, Northeastern Brazil: Ethnopharmacopeia (1980–1990) of the Late Professor Francisco José de Abreu Matos. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 237, 314–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, T.M.G.; de Carvalho Correia, A.C.; dos Santos, R.V.; Lemos, R.P.L.; da Silva, S.A.S.; Barreto, E. The Use of Medicinal Plants in Maceió, Northeastern Brazil: An Ethnobotanical Survey. Medicines 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.; Aparecida, E.; Mendonça, A.C.A.M.; Garcia, Í.R.; Lisboa, M.A.N.; Kamdem, J.P.; Cruz, G.V.; Silva, M.A.P.; Fernandes, G.P.; Júnior, J.T.C. Ethnoknowledge of Medicinal and Mystical Plants Used by Healers in Juazeiro do Norte, Ceará, Northeast Brazil. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2021, 20, 154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Alkmim, R.F. Traditional Knowledge of Medicinal Plants Used by the Xakriabá Ethnic Group. Bachelor′s Thesis, Instituto Federal Goiano—Campus Urutaí, Urutaí, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Macêdo, A.F.; Oshiiwa, M.; Guarido, C.F. Ocorrência Do Uso de Plantas Medicinais Por Moradores de Um Bairro Do Município de Marília-SP. Rev. Ciências Farm. Básica Apl. 2007, 28, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, E.C.S.; Vilar, F.C.R.; Perez, J.O.; Barbosa, J.; Freire, J.L.O.; Lima, A.N.; Dias, T.J. Medicinal Plants of the Caatinga: Ethnobotanical Survey in Open Markets of São Francisco Valley. Eng. Ambient. 2008, 5, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Filho, J.A. Ethnobotanical Study on the Diversity and Use of Medicinal Plants by Residents of the Municipality of Puxinanã, PB. Master′s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Patos, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, E.A.V.; Santos, I.S.; Lima, L.O.P.; Santos, A.P.M.; Lima, A.D.C.; Lima, A.K.V.O. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Species Used by Farmers in Rural Communities of Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2021, 21, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Ferreira, E.; Anselmo, M.D.G.V.; Guerra, N.M.; Silva, T.S.; Oliveira, R.S.; Santos, F.C.; Lima, J.R.; Alves, R.R.N. Local Knowledge and Use of Medicinal Plants in a Rural Community in the Agreste of Paraíba, Northeast Brazil. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 9944357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerschmidt, L.; Silva, R.A.P.; Cabral Sales de Melo, M.R. Use of Medicinal Plants by the Community of Fazenda Nova District, Brejo da Madre de Deus, PE, Brazil. Diversitas J. 2023, 8, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, U.P. Re-Examining Hypotheses Concerning the Use and Knowledge of Medicinal Plants: A Study in the Caatinga Vegetation of NE Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolson, M.; Hefler, S.M.; Dall′Oglio Chaves, E.I.; Gasparotto Junior, A.; Cardozo Junior, E.L. Ethno-Medicinal Study of Plants Used for Treatment of Human Ailments by Residents of the Surrounding Region of Forest Fragments of Paraná, Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 161, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.; Bieski, I.; Balogun, S.; Martins, D. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by Ribeirinhos in the North Araguaia Microregion, Mato Grosso, Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 205, 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Filho, G.B.; Souza Oliveira, M.S.F.; Lemos, M.F.M. The Use of Medicinal Plants for the Healing of Diseases in the Village and Its Relationship with the Work of Blessers and Prayers in the Indigenous Tradition of Tapeba, Potyguara, and Tabajara. Bachelor′s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Monsenhor Tabosa, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, O.; Khanam, Z.; Misra, N.; Srivastava, M.K. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.): An Overview. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2011, 5, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavaroli, A.; Di Simone, S.C.; Sinan, K.I.; Ciferri, M.C.; Angeles Flores, G.; Zengin, G.; Etienne, O.K.; Ak, G.; Fawzi Mahomoodally, M.; Jugreet, S.; et al. Pharmacological Properties and Chemical Profiles of Passiflora foetida L. Extracts: Novel Insights for Pharmaceuticals and Nutraceuticals. Processes 2020, 8, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movafegh, A.; Alizadeh, R.; Hajimohamadi, F.; Esfehani, F.; Nejatfar, M. Preoperative Oral Passiflora incarnata Reduces Anxiety in Ambulatory Surgery Patients: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Anesth. Analg. 2008, 106, 1728–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zick, S.M.; Wright, B.D.; Sen, A.; Arnedt, J.T. Preliminary Examination of the Efficacy and Safety of a Standardized Chamomile Extract for Chronic Primary Insomnia: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepp, J.; Koshovyi, O.; Jakstas, V.; Žvikas, V.; Botsula, I.; Kireyev, I.; Tsemenko, K.; Kukhtenko, O.; Kogermann, K.; Heinämäki, J.; et al. Phytochemical, Technological, and Pharmacological Study on the Galenic Dry Extracts Prepared from German Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) Flowers. Plants 2024, 13, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib-Hajbaghery, M.; Mousavi, S.N. The effects of chamomile extract on sleep quality among elderly people: A clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2017, 35, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.J.; Xie, S.X.; Keefe, J.R.; Soeller, I.; Li, Q.S.; Amsterdam, J.D. Long-term chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.D.; Onusic, G.M.; Poltronieri, S.C.; Viana, M.B. Effect of Erythrina velutina and Erythrina mulungu in Rats Submitted to Animal Models of Anxiety and Depression. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2006, 39, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, R.S.; Amorim, K.S.; Gercina, A.C.; Oliveira, A.C.A.; Menezes, L.S.; Groppo, F.C.; Souza, L.M.A. Herbal medicines as anxiolytics prior to third molar surgical extraction: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira-Souto, M.L.; São-Mateus, C.R.; Almeida-Souza, L.M.; Groppo, F.C. Effect of Erythrina mulungu on anxiety during extraction of third molars. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2014, 19, e518–e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Ding, R.; Lai, C.; Wang, H.; Fan, X.; Chu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Hua, T.; Yuan, H. Vitexin Attenuates Neuropathic Pain by Regulating Astrocyte Autophagy Flux and Polarization via the S1P/S1PR1-PI3K/Akt Axis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 981, 176848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yutharaksanukul, P.; Tangpromphan, P.; Tunsagool, P.; Sae-tan, S.; Nitisinprasert, S.; Somnuk, S.; Nakphaichit, M.; Pusuntisumpun, N.; Wanikorn, B. Effects of Purified Vitexin and Iso-Vitexin from Mung Bean Seed Coat on Antihyperglycemic Activity and Gut Microbiota in Overweight Individuals’ Modulation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, H.; Wen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Huang, W. Vitexin Inhibits TNBC Progression and Metastasis by Modulating Macrophage Polarization Through EGFR Signaling. J. Immunother. 2024, 47, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Shi, L. Vitexin Improves Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Attenuating Oxidative Injury and Ferroptosis via Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling. Neurochem. Res. 2023, 48, 980–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Gu, E.J.; Song, H.-Y.; Yoo, B.-G.; Park, J.E.; Jeon, J.; Byun, E.-B. Exploring the Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Novel Chrysin Derivatives through Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibition. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 50491–50503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, S.; Khodaei Ardakan, A.; Mehdizadeh Aghdam, E.; Mesbahi, A.; Montazersaheb, S.; Molavi, O. Induction of Immunogenic Cell Death and Enhancement of the Radiation-Induced Immunogenicity by Chrysin in Melanoma Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, D.; Sengupta, R. A Review on the Role of Phytoconstituents Chrysin on the Protective Effect on Liver and Kidney. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2024, 21, e251023222716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Jiao, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, M.; Li, Q.; Shabuerjiang, L.; Huang, G.; Song, Q.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Chrysin Inhibits Ferroptosis of Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury via Regulating HIF-1α/CP Loop. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.S.; Zheng, S.; Yin, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Zou, T.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Liao, C.; Xie, Z.; et al. Apigenin Ameliorates Imiquimod-Induced Psoriasis in C57BL/6J Mice by Inactivating STAT3 and NF-κB. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Fan, K.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, M.-L. Apigenin Attenuates TGF-β1-Stimulated Cardiac Fibroblast Differentiation and Extracellular Matrix Production by Targeting miR-155-5p/c-Ski/Smad Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 265, 113195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S. Neuroprotective Effects of Apigenin on Retinal Ganglion Cells in Ischemia/Reperfusion: Modulating Mitochondrial Dynamics in In Vivo and In Vitro Models. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, A. Apigenin: The Anxiolytic Constituent of Turnera aphrodisiaca. Pharm. Biol. 2006, 44, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Shen, F.; Liu, J.; Tang, H.; Teng, X.; Yang, F.; Liu, H. Luteolin Enhanced Antioxidant Capability and Induced Pyroptosis through NF-κB/NLRP3/Caspase-1 in Splenic Lymphocytes Exposure to Ammonia. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeing, T.; da Silva, L.M.; Mariott, M.; de Andrade, S.F.; de Souza, P. Diuretic and Natriuretic Effect of Luteolin in Normotensive and Hypertensive Rats: Role of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017, 69, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtari, T.; Lu, M.; El-Meghawry El-Kenawy, A. Potential Anxiolytic and Antidepressant-Like Effects of Luteolin in a Chronic Constriction Injury Rat Model of Neuropathic Pain: Role of Oxidative Stress, Neurotrophins, and Inflammatory Factors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 122, 110520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos Rosa, D.; Faggion, S.A.; Gavin, A.S.; Dantas, L.P.; Crestani, C.C.; Tavares, R.F.; Santos, C.F.; Oliveira, R.M.W. Erysothrine, an alkaloid extracted from flowers of Erythrina mulungu Mart. ex Benth: Evaluating its anticonvulsant and anxiolytic potential. Epilepsy Behav. 2012, 23, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flausino, O.; Santos, L.Á.; Verli, H.; Pereira, A.M.; Bolzani, V.S.; Nunes-de-Souza, R.L. Anxiolytic Effects of Erythrinian Alkaloids from Erythrina mulungu. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flausino, O.A., Jr.; Pereira, A.M.; Bolzani, V.S.; Nunes-de-Souza, R.L. Effects of Erythrinian Alkaloids Isolated from Erythrina mulungu (Papilionaceae) in Mice Submitted to Animal Models of Anxiety. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Formulário de Fitoterápicos da Farmacopeia Brasileira, 1ª Edição. 2011. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/informacoes_sistematizadas_relacao_maracuja_doce.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Informações Sistematizadas sobre o Maracujá-roxo (Passiflora incarnata). 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/composicao/sectics/daf/cbaf/arquivos/arquivos-plantas-medicinais-e-fitoterapicos/maracuja_vermelho.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Formulário de Fitoterápicos da Farmacopeia Brasileira, 2ª Edição. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/farmacopeia/formulario-fitoterapico/arquivos/2021-fffb2-final-c-capa2.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- ANVISA—Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Consultations. Available online: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/medicamentos/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada—RDC nº 26, de 13 de maio de 2014. Establishes the Registration of Herbal Medicines and Traditional Herbal Products. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2014/rdc0026_13_05_2014.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Política Nacional de Práticas Integrativas e Complementares no SUS—PNPIC. Brasília. 2006. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/pnpic.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).