Providers’ Perspectives on Communication Barriers with Language-Discordant Patients in the Critical Care Setting: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Quality Assessment

3. Results

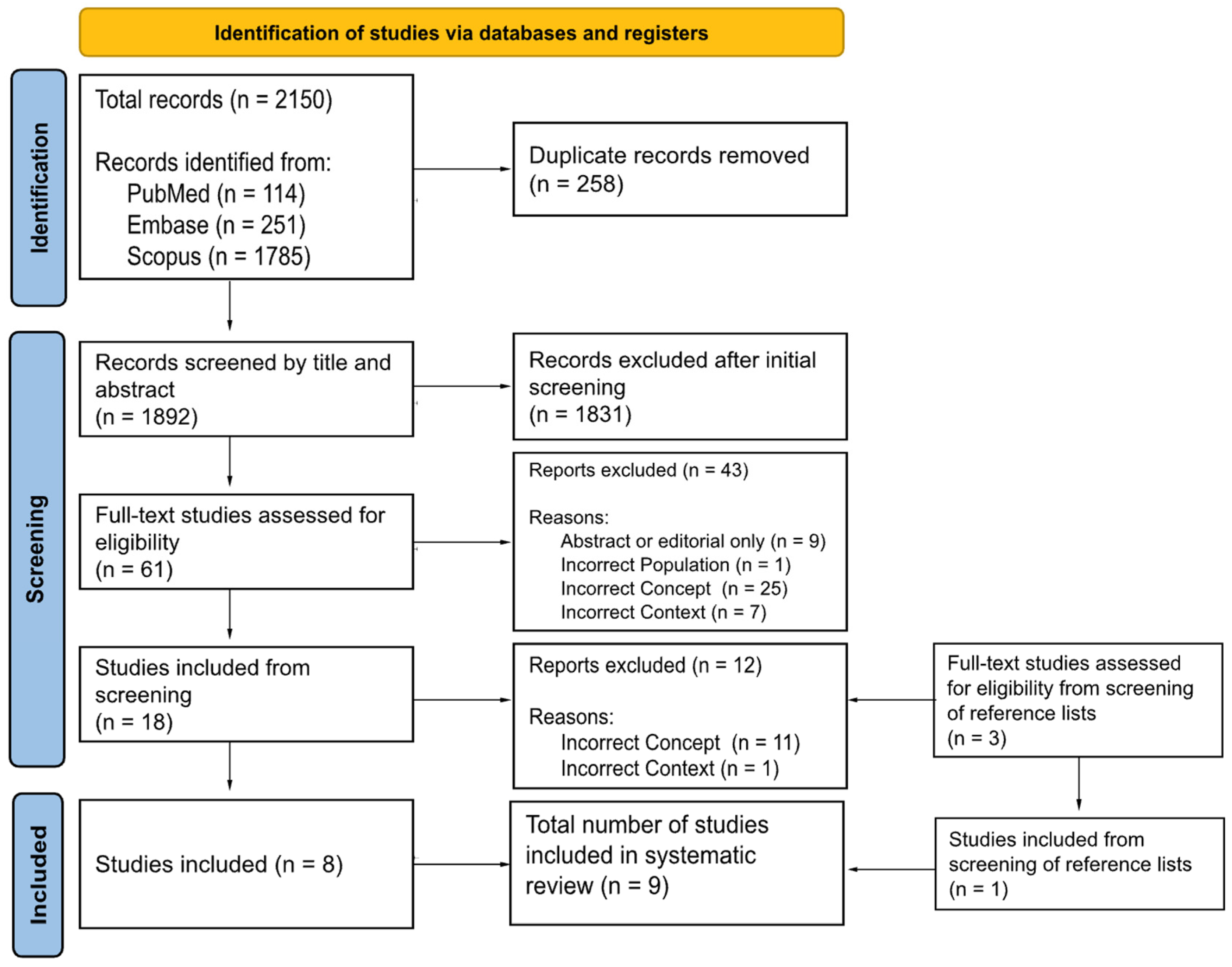

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Study Setting

3.4. Study Participants

3.5. Study Design

3.6. Quality of Included Studies

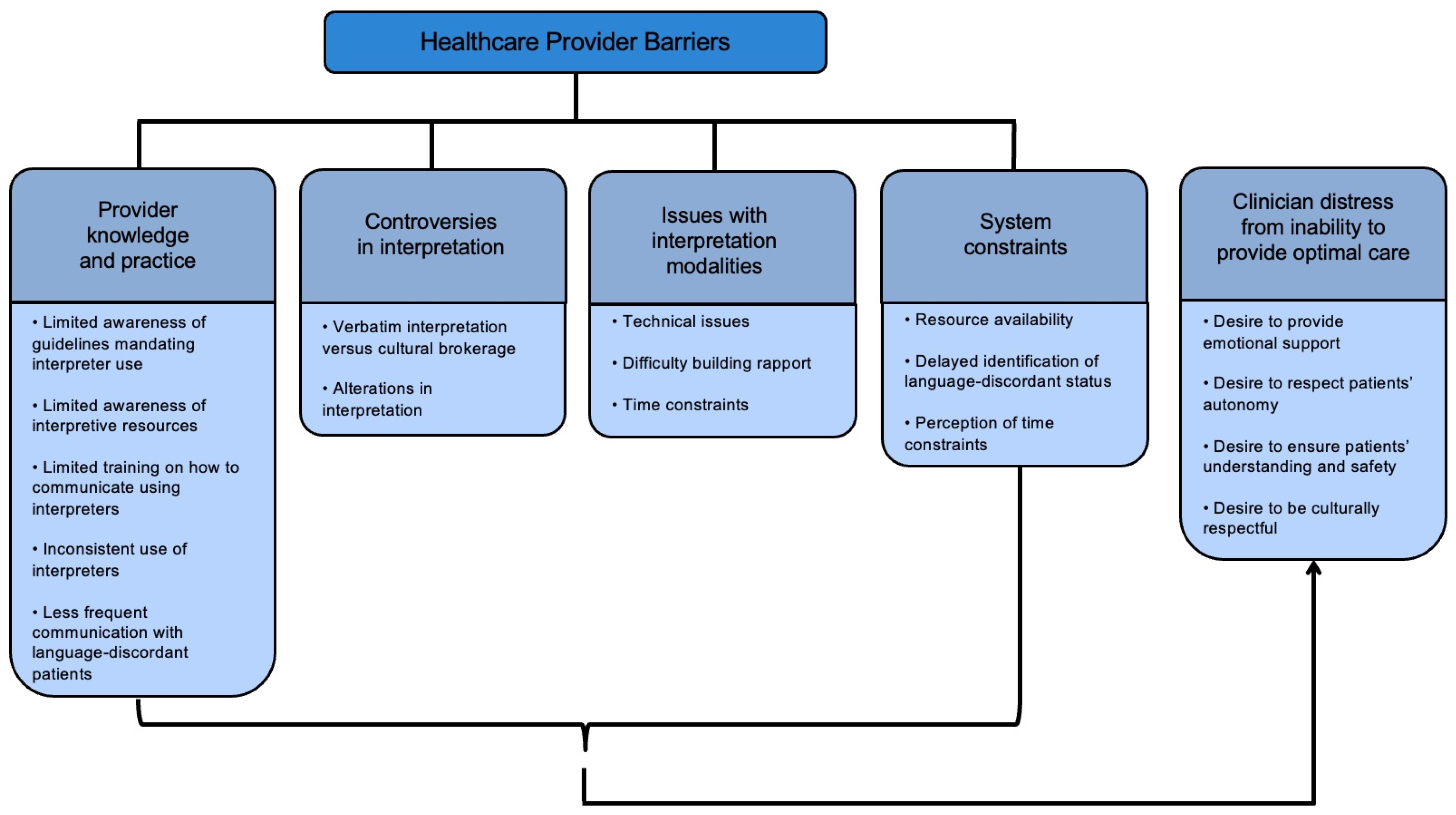

3.7. Themes

3.8. Provider Knowledge and Practice

3.8.1. Limited Awareness of Guidelines Mandating Professional Interpreter Use

3.8.2. Limited Awareness of Interpretive Resources

3.8.3. Limited Training on How to Communicate Using Professional Interpreters

3.8.4. Inconsistent Use of Professional Interpreters

3.8.5. Less Frequent Communication with Language-Discordant Patients

3.9. Controversies in Interpretation

3.9.1. Verbatim Interpretation Versus Cultural Brokerage

3.9.2. Alterations in Interpretation

3.10. Issues with Interpretation Modalities

3.10.1. Technical Issues

3.10.2. Difficulty Building Rapport

3.10.3. Time Constraints

3.11. System Constraints

3.11.1. Resource Availability

3.11.2. Delayed Identification of Language-Discordant Status

3.11.3. Perception of Time Constraints

3.12. Clinician Distress Stemming from Inability to Deliver Optimal Care for Language-Discordant Patients

3.12.1. Desire to Provide Emotional Support

3.12.2. Desire to Respect Patients’ Autonomy

3.12.3. Desire to Ensure Patients’ Understanding and Safety

3.12.4. Desire to Be Culturally Respectful

4. Discussion

4.1. Provider Knowledge and Practice

4.2. Controversies in Interpretation

4.3. Issues with Interpretation Modalities

4.4. System Constraints

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

7. Strengths and Weaknesses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary of Terms

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| LEP | limited English-proficient |

| NHLBI | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| US | United States |

References

- Sears, J.; Khan, K.; Ardern, C.I.; Tamim, H. Potential for patient-physician language discordance in Ontario. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Census Bureau. Language Spoken at Home. Census.gov Web Site. Available online: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/language/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- McAuliffe, M.; Oucho, L.A. World Migration Report 2024; International Organization for Migration (IOM): Grand Saccone, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, M. Medical interpreting and the law in the European Union. Eur. J. Health Law 2012, 19, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershengorn, H.B.; Patel, S.; Mallow, C.M.; Falise, J.; Sosa, M.A.; Parekh, D.J.; Ferreira, T. Association of language concordance and restraint use in adults receiving mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 49, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barwise, A.; Jaramillo, C.; Novotny, P.; Wieland, M.L.; Thongprayoon, C.; Gajic, O.; Wilson, M.E. Differences in Code Status and End-of-Life Decision Making in Patients With Limited English Proficiency in the Intensive Care Unit. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriers to and Challenges in Health Care Utilization by Patients with Limited-English Proficiency in the Critical Care Setting: A Scoping Review Protocol. OSF Registries Web Site. Available online: https://osf.io/jry4z (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Qualitative Study) Checklist. 2023. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2017. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Barwise, A.K.; Nyquist, C.A.; Suarez, N.R.E.; Jaramillo, C.; Thorsteinsdottir, B.; Gajic, O.; Wilson, M.E. End-of-Life Decision-Making for ICU Patients With Limited English Proficiency: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Team Insights. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.; Angosta, A.D. The lived experiences of acute-care bedside registered nurses caring for patients and their families with limited English proficiency: A silent shift. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, N.R.E.; Urtecho, M.; Nyquist, C.A.; Jaramillo, C.; Yeow, M.-E.; Thorsteinsdottir, B.; Wilson, M.E.; Barwise, A.K. Consequences of suboptimal communication for patients with limited English proficiency in the intensive care unit and suggestions for a way forward: A qualitative study of healthcare team perceptions. J. Crit. Care 2021, 61, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listerfelt, S.; Fridh, I.; Lindahl, B. Facing the unfamiliar: Nurses’ transcultural care in intensive care—A focus group study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 55, 102752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalec, B.; Maiden, K.M.; Ortiz, J.; Bell, A.V.; Ehrenthal, D.B. Providers’ Perceptions of Medical Interpreter Services and Limited English Proficiency (LEP) Patients. J. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2014, 9, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriksson, K.; Wigert, H.; Berg, M.; Nilsson, S. Health care professional’s communication through an interpreter where language barriers exist in neonatal care: A national study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patriksson, K.; Nilsson, S.; Wigert, H. Conditions for communication between health care professionals and parents on a neonatal ward in the presence of language barriers. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2019, 14, 1652060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, K.; Thornton, J.D.; Engelberg, R.A.; Jackson, J.C.; Curtis, J.R. Alterations During Medical Interpretation of ICU Family Conferences That Interfere with or Enhance Communication. Chest 2009, 134, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, N.R.E.; Urtecho, M.; Jubran, S.; Yeow, M.-E.; Wilson, M.E.; Boehmer, K.R.; Barwise, A.K. The Roles of medical interpreters in intensive care unit communication: A qualitative study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.; Abreu, M.; Barone, C.P.; Bachur, R.; Lin, H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: A comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2012, 60, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karliner, L.S.; Jacobs, E.A.; Chen, A.H.; Mutha, S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 727–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juckett, G.; Unger, K. Appropriate use of medical interpreters. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 90, 476–480. [Google Scholar]

- Slusarz, C. The roles and experiences of medical interpreters in palliative care: A narrative review. Palliat. Support. Care 2023, 22, 2158–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.D.; Adelman, R.D.; Singh, V.; Gupta, R.; Moxley, J.; Sobota, R.M.; Tsai, S.; Abel, B.T.; Reid, M.C. Healthcare Provider Perspectives Regarding Use of Medical Interpreters During End-of-Life Conversations with Limited English Proficient Patients. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2022, 39, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karliner, L.S.; Perez-Stable, E.J.; Gildengorin, G. The language divide. The importance of training in the use of interpreters for outpatient practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2004, 19, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazori, A.Y.; Maron, M.I.; Osterbur, M.L.; Santos, D.; Marco, V.F.; Lin, J.; Cortijo, A.; Nosal, S.; Schoenbaum, E. Enhancing Medical Student-Interpreter Collaboration in an Urban Free Clinic. Fam. Med. 2019, 51, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, M.; Santos, M.T.; Marzan, M.; Green, E.H.; Milan, F.B. Teaching medical students how to use interpreters: A three year experience. Med. Educ. Online 2009, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.; Flora, J.; Basaviah, P.; Bryant, M.; Hosamani, P.; Westphal, J.; Kugler, J.; Hom, J.; Chi, J.; Parker, J.; et al. Interpreter and limited-English proficiency patient training helps develop medical and physician assistant students’ cross-cultural communication skills. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagels, P.; Kindratt, T.; Arnold, D.; Brandt, J.; Woodfin, G.; Gimpel, N. Training Family Medicine Residents in Effective Communication Skills While Utilizing Promotoras as Standardized Patients in OSCEs: A Health Literacy Curriculum. Int. J. Family Med. 2015, 2015, 129187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, N.; Partain, D.K.; Yeow, M.; Farfour, H.N.; Prokop, L.; Barwise, A. Learning to collaborate with medical interpreters in health professions education: A systematic review of training programs. Med. Teach. 2024, 46, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, A.D.; Dale, S.; Verbitsky-Savitz, N.; Andrecheck, S.; Zavotsky, K.; Eisenstein, R. Examining effectiveness of medical interpreters in emergency departments for Spanish-speaking patients with limited English proficiency: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2011, 57, 248–256.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatis, C.; Williamson, D.; Gould-Kabler, C.; Zone-Smith, L.; Detzler, I.; Roberson, J.; Maisiak, R.; Ackerman, M. Comparing in-person, video, and telephonic medical interpretation. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, T.R.; Leder, K.; Akinci, I.; Biggs, B. Improvements in patient care: Videoconferencing to improve access to interpreters during clinical consultations for refugee and immigrant patients. Aust. Health Rev. 2015, 39, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M.; Jeemi, Z.; Norman, R.; Dantas, J.A.R. Professional Interpreter Services and the Impact on Hospital Care Outcomes: An Integrative Review of Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L.; Fischer, A.; Noyes Soeller, A.; Cordova, R.; Gutierrez, Y.R.; Alford, L. Creating a Professional Ladder for Interpreters for Improvement of Care. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2016, 42, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masland, M.C.; Lou, C.; Snowden, L. Use of communication technologies to cost-effectively increase the availability of interpretation services in healthcare settings. Telemed. J. E Health 2010, 16, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajbhandari, P.; Keith, M.F.; Braidy, R.; Gunkelman, S.M.; Smith, E. Interpreter Use for Limited English Proficiency Patients/Families: A QI Study. Hosp. Pediatr. 2021, 11, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miazzi, M.M.; Pasqualone, A.; Zammit-Mangion, M.; Savoia, M.A.; Fanelli, V.; Procino, S.; Gadaleta, S.; Aurelio, F.L.; Montemurro, C. Improving Identification of Interpreter Need in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022057330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strings | Database | Date Accessed |

|---|---|---|

| (“limited English proficien*” or “primary language” or “second language” or “language preference”) and (“intensive care unit” or “ICU” or “critical care”) | PubMed, Scopus | 20 February 2024 |

| (“limited English proficien*” or “primary language” or “second language” or “language preference”) AND (“intensive care unit” or “ICU” or “critical care”) | Embase | 21 February 2024 |

| Author (Year) [Ref. #] | Location | Setting | Participants’ Characteristics | Number of Participants (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barwise (2019) [11] | Rochester, Minnesota, US | 3 adult ICUs in a large academic hospital | 16 physicians, 12 nurses, 12 interpreters | 40 |

| Coleman (2016) [12] | Las Vegas, Nevada, US | Adult acute care unit | 40 nurses | 40 |

| Espinoza Suarez (2021) [13] | Rochester, Minnesota, US | 3 adult ICUs in a large academic hospital | 16 physicians, 12 nurses, 12 interpreters | 40 |

| Listerfelt (2019) [14] | Sweden | 2 adult ICUs | 15 nurses | 15 |

| Michalec (2015) [15] | Newark, Delaware, US | Neonatal ICU in an academic community hospital | 36 providers, including postpartum nurses, labor and delivery/triage nurses, obstetric resident physicians, neonatal nurses, and attending physicians, nurse practitioners, and midwives | 36 |

| Patriksson (2019) [16] | Sweden | All neonatal units in Sweden | 858 providers including physicians, registered nurses, and nurse assistants | 858 |

| Patriksson (2019) [17] | Sweden | 3 neonatal ICUs | 10 parents and 10 providers including physicians, nurses, and nurse assistants | 10 |

| Pham (2008) [18] | Seattle, Washington, US | Adult ICUs in a large academic hospital and a community hospital | 9 physicians, 10 nurses, 26 non-nurse/physician clinicians, 70 families of patients | 45 |

| Suarez (2020) [19] | Rochester, Minnesota, US | 3 adult ICUs in a large academic hospital | 16 physicians, 12 nurses, 12 interpreters | 40 |

| Author (Year) [Ref. #] | Objective | Study Design | Analysis | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barwise (2019) [11] | To assess the perceptions of healthcare team members about the factors that influence end-of-life discussions and decisions for patients and family members with LEP in the ICU | Qualitative study with 1:1 interviews | Transcripts were coded to develop themes. | Language-discordant patients had less frequent clinician communication, impaired relationship building and understanding, and different cultural values and decision-making processes. |

| Coleman (2016) [12] | To explore the lived experiences of acute-carebedside nurses caring for patients and their families with LEP | Qualitative study with 1:1 interviews | Transcripts were coded to develop themes. | Clinicians had a desire to communicate, connect, provide good care, and be culturally respectful. |

| Espinoza Suarez (2021) [13] | To understand the healthcare team’s perceptions of the negative consequences of suboptimal communication | Qualitative study with 1:1 interviews | Transcripts were coded to develop themes. | Suboptimal communication may lead to the suboptimal assessment and treatment of patients’ symptoms, unmet expectations of patients and their families, decreased patients’ autonomy, unmet end-of-life wishes, and clinician distress. |

| Listerfelt (2019) [14] | To explore nurses’ experiences in caring for culturally diverse ICU patients | Qualitative study with focus groups | Transcripts were coded to develop themes. | Nursing staff caring for culturally diverse patients described challenges due to linguistic and cultural barriers. |

| Michalec (2015) [15] | To understand providers’ perspectives on working with PMIs | Qualitative study with focus groups | Transcripts were coded to develop themes. | Barriers to the utilization of PMIs include institutional barriers such as time and resource constraints and provider-level barriers such as personal biases. |

| Patriksson (2019) [16] | To examine healthcare professionals’ use of PMI and awareness of local guidelines for interpreted communication in neonatal care | Cross-sectional study using data from a national survey | Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test Fisher’s nonparametric permutation test | Barriers to the utilization of PMIs included lack of awareness of language legislation, unavailability of PMIs, use of PMIs in selective situations, and use of untrained interpreters. Nurse assistants had less awareness of best practices for PMI use compared with other provider types. |

| Patriksson (2019) [17] | To describe communication between neonatal healthcare professionals and parents in the presence of language barriers | Qualitative study with 1:1 interviews; observations from a field study | Transcripts were coded to develop themes. Themes were also extracted from a field study. | Providers preferred to use PMIs when communicating with patients’ parents, while patients’ parents preferred friends for interpretation or multilingual providers. |

| Pham (2008) [18] | To characterize the types, prevalence, and potential effects of alterations in interpretation during family conferences involving end-of-life discussions in the ICU | Qualitative study with 1:1 interviews | Interpretation alterations were grouped as additions, omissions, substitutions, and editorializations, then assessed for impact on communication. | There was a 55% chance of alteration during interpreted exchanges between clinicians and patients’ families. Over 75% of alterations had a potentially clinically significant impact. Of these potentially significant alterations, 93% were likely to have a negative effect. |

| Suarez (2020) [19] | To understand healthcare team perceptions of the role of PMI and interpretation modalities during end-of-life and critical illness discussions with patients and families who have LEP in the ICU | Qualitative study with 1:1 interviews | Transcripts were coded to develop themes. | The roles of PMIs included verbatim interpretation, health literacy guardian, and cultural broker. Clinicians acknowledged advantages and disadvantages to each interpretation approach. |

| Author (Year) [Ref. #] | Scale Used | Rating | Quality | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barwise (2019) [11] | CASP Qualitative | 7/10 | Moderate |

|

|

| Coleman (2016) [12] | CASP Qualitative | 7/10 | Moderate |

|

|

| Espinoza Suarez (2021) [13] | CASP Qualitative | 7/10 | Moderate |

|

|

| Listerfelt (2019) [14] | CASP Qualitative | 8/10 | High |

|

|

| Michalec (2015) [15] | CASP Qualitative | 7/10 | Moderate |

|

|

| Patriksson (2019) [16] | NHLBI Quality Assessment | 5/14 | Low |

|

|

| Patriksson (2019) [17] | CASP Qualitative | 6/10 | Moderate |

|

|

| Pham (2008) [18] | CASP Qualitative | 9/10 | High |

|

|

| Suarez (2020) [19] | CASP Qualitative | 9/10 | High |

|

|

| Themes | Articles Referenced |

|---|---|

| Provider Knowledge and Practice | |

| Limited awareness of guidelines mandating professional interpreter use | [16] |

| Limited awareness of interpretive resources | [13] |

| Limited training on how to communicate using professional interpreters | [16] |

| Inconsistent use of professional interpreters | [16] |

| Less frequent communication with language-discordant patients | [11] |

| Controversies in Interpretation | |

| Verbatim interpretation versus cultural brokerage | [11,17,19] |

| Alterations in interpretation | [18] |

| Issues with Interpretation Modalities | |

| Technical issues | [15,16,19] |

| Difficulty building rapport | [11,12,19] |

| Time constraints | [14,19] |

| System Constraints | |

| Resource availability | [11,14,15,16,17,19] |

| Delayed identification of language-discordant status | [15,17] |

| Perception of time constraints | [12,14,15] |

| Clinician Distress Stemming from Inability to Deliver Optimal Care for Language-Discordant Patients | |

| Desire to provide emotional support | [12] |

| Desire to respect patients’ autonomy | [11,13] |

| Desire to ensure patients’ understanding and safety | [11,12] |

| Desire to be culturally respectful | [11,15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, H.S.; Tsao, A.J.; Kim, M.I.; Luan-Erfe, B.M. Providers’ Perspectives on Communication Barriers with Language-Discordant Patients in the Critical Care Setting: A Systematic Review. Anesth. Res. 2025, 2, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/anesthres2010007

Seo HS, Tsao AJ, Kim MI, Luan-Erfe BM. Providers’ Perspectives on Communication Barriers with Language-Discordant Patients in the Critical Care Setting: A Systematic Review. Anesthesia Research. 2025; 2(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/anesthres2010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Hyun Seong, Amanda J. Tsao, Michael I. Kim, and Betty M. Luan-Erfe. 2025. "Providers’ Perspectives on Communication Barriers with Language-Discordant Patients in the Critical Care Setting: A Systematic Review" Anesthesia Research 2, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/anesthres2010007

APA StyleSeo, H. S., Tsao, A. J., Kim, M. I., & Luan-Erfe, B. M. (2025). Providers’ Perspectives on Communication Barriers with Language-Discordant Patients in the Critical Care Setting: A Systematic Review. Anesthesia Research, 2(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/anesthres2010007