Giant Bird Tracks (Family Gastornithidae) from the Paleogene Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington, USA, with a Review of Gastornis Distribution

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Landslide History

1.2. Gastornithid Footprints at Racehorse Creek Landslide

1.3. Gastornithid Tracks from Racehorse Creek

1.4. Previous Gastornithid Track Reports

2. Geologic Setting

2.1. Age and Stratigraphy

2.2. Chuckanut Formation Paleontology

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Morphometric Data

4.2. Locomotion Evidence from the Racehorse Creek Trackway

4.3. Paleoenvironment

5. Discussion

5.1. Previous Research

5.2. Paleoecology

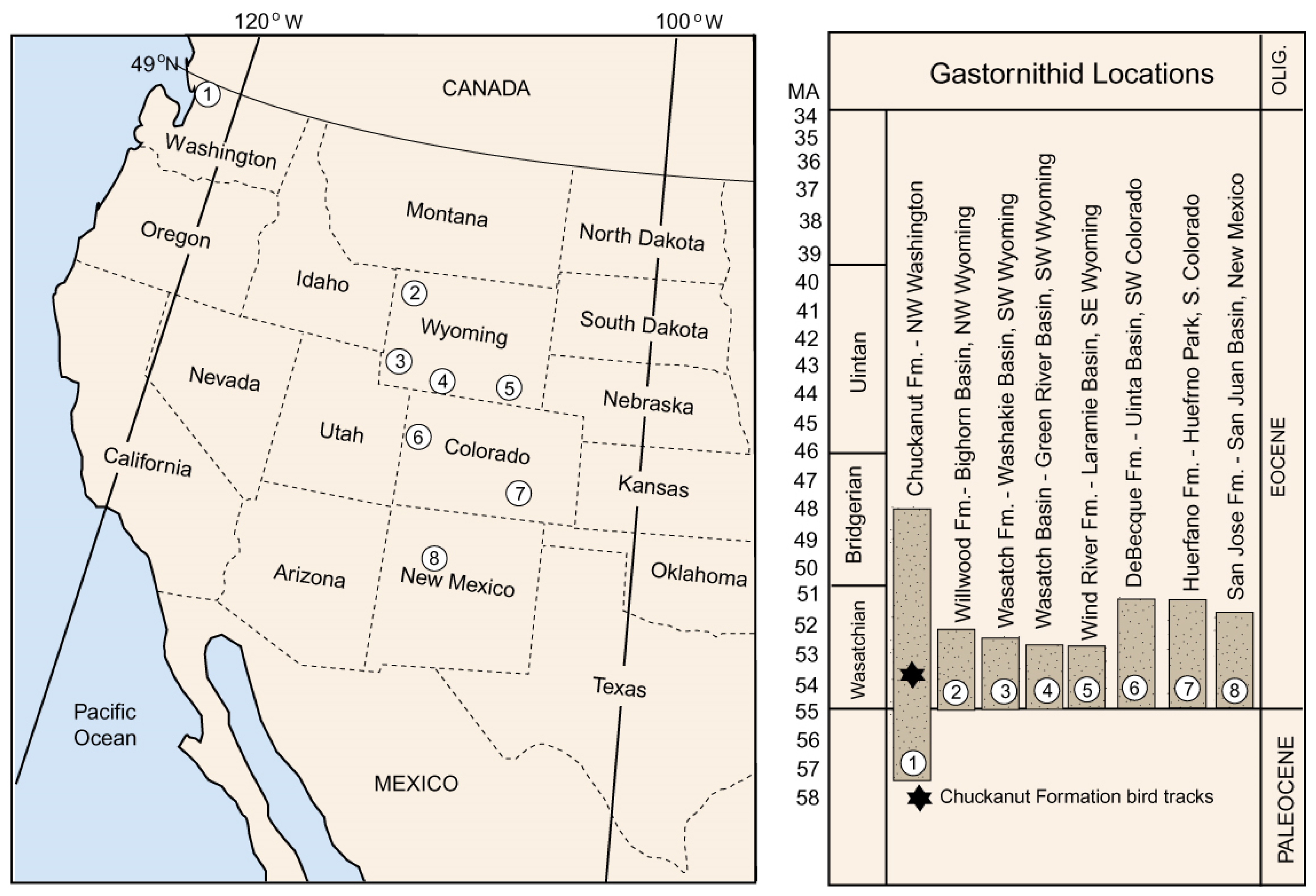

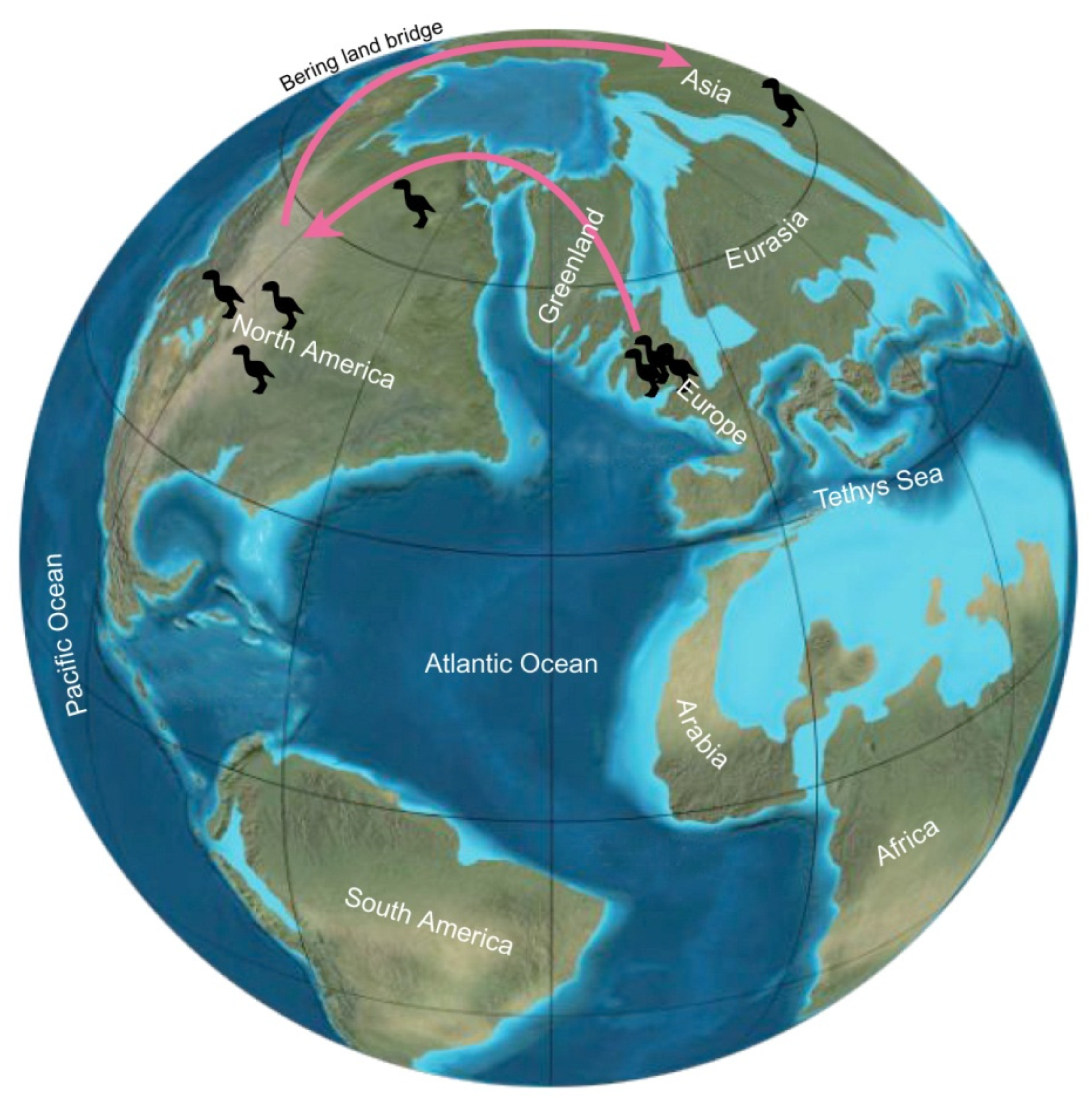

5.3. Geologic and Geographic Range

5.4. Other Fossil Evidence of Gastornithids

5.5. Eggs

5.6. Possible Sexual Dimorphism

6. Summary

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crider, J.G.; Tucker, D.S.; Clark, D.H.; Linneman, S.R. The 2009 Racehorse Creek Landslide: Forensic dynamics of a large, complex catastrophic mass movement. In Proceedings of the 2009 Portland Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, Portland, OR, USA, 18–21 October 2009; Volume 41, p. 498. [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe, G.E.; Tucker, D.S.; Kemplin, K.I. Giant Eocene bird footprints from northwest Washington, USA. Palaeontology 2012, 55, 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, B.H.; Brunengo, M. Racehorse Creek Landslide Zonation Project, Whatcom County; Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources: Olympia, WA, USA, 2006; 43p.

- George, O. GIS Investigation of Scarps on Slide Mountain, Western Whatcom County, Washington. Masters’ Thesis, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA, USA, 2012; 80p. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.Y. Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Tectonic Setting of the Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 1984; 221p. [Google Scholar]

- Lapin, T.J. Geologic Map of the Bellingham 1:100,000 Quadrangle, Open-File Report 2000-5, Washington; Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources: Olympia, WA, USA, 2000.

- Racehorse Creek, Washington Geologic Survey/Department of Natural Resources, Olympia, WA, USA. Available online: https://wa100.dnr.wa.gov/north-cascades/racehorse-creek (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Buffetaut, E. Footprints of giant birds from the Upper Eocene of the Paris Basin: An ichnological enigma. Ichnos 2004, 11, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andors, A.V. Report on an Alleged Avian Footprint from the Eocene of King County Washington; Unpublished report; Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History: New York, NY, USA, 1992; 9p. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J.; Lockley, M.G. A probable Diatryma track from the Eocene of Washington: An intriguing case of controversy and skepticism. Ichnos 2004, 11, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.Y. Stratigraphy, age, and paleogeography of the Eocene Chuckanut Formation. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1984, 27, 2–106. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.Y. Fluvial sedimentation in a rapidly subsiding basin. Sediment. Geol. 1984, 38, 361–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.Y. Eocene strike-slip faulting and nonmarine basin formation in Washington. In Strike-Slip Deformation, Basin Formation, and Sedimentation; Biddle, K.T., Christie-Blick, N., Eds.; Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists Special Publication 37; Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1985; pp. 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe, G.E.; Gannaway, W.L. Paleogeography and paleontology of the early Tertiary Chuckanut Formation, northwest Washington. Northwest Geol. 1997, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Haugerud, R. Preliminary report on significant thrusting and extension of the Earl Tertiary Chuckanut Formation, NW Washington. In Slave-Northern Cordillera Lithospheric Extension (SNORCLE) and Cordilleran Teconics Workshop; Cook, F., Erdmer, P., Eds.; Lithoprobe Report; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1998; 203p. [Google Scholar]

- Breedlovestrout, R.L. Paleofloristic Studies in the Paleogene Chuckanut Basin, Western Washington, USA. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA, 2011; 953p. [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe, G.E. The first discovery of a fish fossil (Phareodus sp.) from Paleogene fluvial deposits in Western Washington State, USA. Geosciences 2023, 13, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesquereux, L. On fossil plants collected by Dr. John Evans at Vancouver Island and at Bellingham Bay, Washington Territory. Am. J. Sci. 1859, 28, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. Descriptions of fossil plants collected by Mr. George Gibbs. Boston J. Nat. Hist. 1863, 7, 506–524. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, J.S. The Later Extinct Floras of North America; U.S. Geological Survey Monograph 35; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1898; 295p.

- Knowlton, F.H. Preliminary Report on Fossil Plants from the State of Washington, Collected by Henry Landes, 1901; Washington Geological Survey Annual Report, Part 1; Washington Geological Survey: Olympia, WA, USA, 1902; pp. 30–31.

- Pabst, M.B. The Flora of the Chuckanut Formation of Northwestern Washington—The Equisitales, Filicales, Coniferales; University of California Publications in Geological Sciences v. 6; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1968; 85p. [Google Scholar]

- Reiswig, K.N. Palynologic Differences Between the Chuckanut and Huntingdon Formation, Northwestern Washington. Masters’ Thesis, Western Washington University, Bellingam, WA, USA, 1982; 61p. [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe, G.E.; Girouard, S.P., Jr. A fossil trionychid turtle from the early Tertiary Chuckanut Formation of northwestern Washington. Northwest Sci. 2001, 75, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe, G.E. Invertebrate trace fossils in Paleogene fluvial strata in western Washington, USA. Ichnos 2023, 29, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, G.E. Lower Eocene footprints from northwest Washington, USA. Part 1: Reptile tracks. Geosciences 2019, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedlovestrout, R.L.; Evraets, B.J.; Parrrish, F.T. New Paleogene paleoclimate analysis of western Washington using physiognomic characteristics of leaves. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeocol. 2013, 392, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachos, J.; Pagani, M.; Sloan, L.; Thomas, E.; Billups, K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma topresent. Science 2001, 282, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachos, J.C.; Dickens, G.R.; Zeebe, R.E. An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature 2008, 451, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, G.E. Eocene bird tracks from the Chuckanut Formation, northwest Washington. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1993, 30, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, G.E. Eocene bird, reptile, and mammal tracks from the Chuckanut Formation, northwest Washington. Palaios 2002, 17, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, G.E.; Dillhoff, R.M.; Dillhoff, T.A. Geology and paleontology of the early Tertiary Chuckanut Formation. In Floods, Faults, and Fire. Geological Field Trips in Washington State and Southwest British Columbia; Stelling, P., Tucker, D.S., Eds.; Geological Society of America Field Guide 9; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2007; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Marnola-Gijarro, A.; Nudds, R.; Folkow, L.; Codd, J. Examining the accuracy of trackways for predicting gait selection and speed of locomotion. Front. Zool. 2020, 17, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Abourachid, A. Bipedal locomotion in birds: The importance of functional parameters in terrestrial adaptation in Anatidae. Can. J. Zool. 2000, 78, 1994–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andors, A.V. Giant Groundbirds of North America (Aves Diatrymidae). Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 1988; 577p. [Google Scholar]

- Andors, A.V. Paleobiology and relationship of the giant ground bird Diatryma (Aves Gastornithiformes). In Proceedings of the Twentieth International Ornithological Congress Wellington, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2–9 December 1990; pp. 536–571. [Google Scholar]

- Andors, A.V. Reappraisal of the Eocene groundbird Diatryma (Aves, Anserimorphae). In Papers in Avian Paleontology Honoring Pierce Brodkorp, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, Science Series; Campbell, K.E., Jr., Ed.; Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1992; Volume 38, pp. 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Andors, A.V. Diatryma among the dinosaurs. Nat. Hist. 1995, 104, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Buffetaut, E.; Angst, D. “Terrorcranes” or peaceful plant eaters: Changing interpretations of the paleobiology of gastornithidbirds. Rev. Paláobiologie 2013, 32, 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, D.; Buffetaut, E.; Lecuyer, C.; Amiot, R. A new method for estimating locomotion type in large groundbirds. Palaeontology 2016, 59, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usherwood, R.U. Why not walk faster? Biol. Lett. 2005, 1, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eadward Muybridge: Feet Off the Ground. The Guardian. 4 September 2010. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/sep/04/eadweard-muybridge-exhibition-rebecca-solnit (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Lockley, M. Tracking Dinosaurs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; 238p. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, W.D.; Granger, W. The skeleton of Diatryma, a gigantic bird from the Lower Eocene of Wyoming. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1917, 37, 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, M.W.; Hayward, M.D. Waterhole use by African fauna. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 2012, 42, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevost, C. Annonce de la dècouverte d’un oisseau fossiled et aillegiantes que, trouvéá la parie del’argile plastique des terrains paresiens. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Séances L’académie Sci. 1855, 40, 554–557. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert, E. Note sur le tibia du Gastornis parisiensis. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Séances L’académie Sci. 1855, 40, 579–582. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert, E. Note sur le femur du Gastornis parisiensis. Comptes Rendus Hebd. des Séances de L’académie des Sci. 1855, 40, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, V. Recherches sur la Oiseaux Fossils des Terrains Tertiares Infériurs des Environs de Reims; Imprimerie et Lithographie F. Keller: Reims, France, 1878; 69p. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, V. Recherches sur la Oiseaux Fossils des Terrains Tertiares Infériurs des Environs de Reims; Deuxième partie, Matot-Braine: Reims, France, 1881; pp. 75–170. [Google Scholar]

- Dollo, L. Note sur la presence du Gastornis Edwardsii, Lemone dans l’ assisse inférieure de l’étage Landénien à Mesvin, près Mions. Bull. Roy. Hist. Nat. Belg. 1883, 2, 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, E.T. On the remains of a gigantic species of bird (Gastornis klaaseni n.sp.) from the Lower Eocene beds near Croyden. Trans. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1886, 12, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, E.D. On a gigantic bird from the Eocene of New Mexico. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. USA 1876, 28, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, O.C. A gigantic bird from the Eocene of New Jersey. Am. J. Sci. 1984, 48, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurfeldt, R.W. Further studies of fossil birds with descriptions o new and extinct species. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1913, 32, 274–284. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub, S. Ein Ratite beckenaus dem Bohnerz von Egerkingen. Ecol. Geol. Helv. 1928, 33, 274–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard, O.C. Un oisseux géant dans le depots éocenes du Mont-d’Or Lyonnais. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Séances L’académie Sci. 1936, 202, 965–967. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, K. Der Riesenlauvogels Diatryma aus dem Eozä Braunkhole des Geieltales. Hallesches Jahrbuh Für Mittelduetsche Erdgescguchte 1962, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, K. Neue Restedes Riesenlauvogels Diatryma aus dem Eozänendes Gieletales bie Halle (DDR). Mitteilungenaus dem Zoologischen Museum in Berlin, Band 54, Supllement Heft. Ann. Für Ornothologie 1978, 2, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, D.E. Nacheis des Riesenlaufvogels Diatryma in Eozänvon Messelbei Dharmstadt/Hessen. Notziblattdes Hessischen Landesmates Für Bodenforschubgzu Weisbanden 1965, 93, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.D. The status of the Late Paleocene birds Gastornis and Remiornis. Nat. Hist. Mus. Los Angeles Sci. Ser. 1992, 36, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, D.; Bufetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Amiot, R. “Terror birds” (Phorusracidae) from the Eocene of Europe imply trans-Tethys dispersal. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, G. Paleogene Fossil Birds; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; 262p. [Google Scholar]

- Buffetaut, E. New remains of the giant bird Gastornis from the Upper Paleocene of the eastern Paris Basin and relationships between Gastornis and Diatryma. Nues Jahrb. Für Geol. Und Paläntologie. Monatscheft 1977, 3, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E. L’Oiseux geant Gastornis; Interpretation, reconstitution et vulgarization de fossils inhabituels dans le France du XIXe siècle. Bull. Société Géologique Fr. 1997, 168, 805–811. [Google Scholar]

- Buffetaut, E. Are Gastornis and Diatryma cogeneric? Vertebr. Pal-Asiat. 2000, 38, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Milikovsky, J. Cenozoic Birds of the World. Part 1: Europe; Ninox Press: Prague, Czech Republic, 2002; pp. 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon, E.; Mourer-Chauviré, C.; Laurent, Y. Early Eocene birds from la Bourie, southern France. Act Paleontol. Pol. 2016, 61, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Buffetat, E. The giant bird Gastornis in Asia: A revision of Zhongaunus xichaunensis Hou 1980, from Early Eocene of China. Palaeontol. J. 2013, 47, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E. First evidence of the giant bird Gastornis from southern Europe: A tibiotarsus from the Lower Eocene of Sainte-Papoul (Aude, southern France). Oryctos 2008, 7, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, D.; Buffetaut, E. First mandible of Gastornis HÉBERT, 1855 (Aves, Gastornithidae) from the Thanetian (Paleocene) of Mont-de-Berru (France). Rev. Paléobiologie 2013, 32, 423–432. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, D.; Lécuyer, C.; Amiot, R.; Buffetaut, E.; Fourel, F.; Martineu, F.; Legendre, S.; Abourachid, A.; Herrel, A. Isotopic and anatomical evidence of an herbivorous diet in the Early Tertiary giant bird Gastornis. Implications for the structure of Paleocene terrestrial cosystems. Naturwissenschaften 2014, 101, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E.; Angst, D. Stratigraphic distribution of large flightless birds in the Palaeogene of Europe. In First Internatonal Congress on Stratigraphy; Rocha, R., Pais, J., Kulberg, J.C., Finney, S., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1005–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, D.; Buffetaut, E. Paleobiology of Giant Flightless Birds; ISTE Press—Elsevier: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Buffetaut, E.; dePloëg, G. Giant birds from the Uppermost Paleocene of Rivecourt (Oise, Northern France). Bolletim Cent. Port. Geo-História Pré-História 2020, 2, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Buffetaut, E.; Angst, D. An Introduction to Evolution and Paliobiology of Flightless Birds. Diversity 2022, 14, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E. The Unfinished Story of the Early Tertiary Giantbird Gastornis. Dansk Geologisk Forening, DGF Online Series. Available online: https://2dgf.dk/dgf-online-series/the-unfinished-story-of-the-early-tertiary-giant-bird-gastornis/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Milne-Edwards, A. Etude sur les rapports zoologiques du Gastornis parisiensis. Ann. Sci. Nat. Zool. Paléont. 1867, 7, 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Troxell, E.L. Diatryma, a colossal heron. Am. J. Sci. 1931, 22, 18034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R. On the affinities of the large extinct bird (Gastornis parisiensis, Hébert), indicated by a fossil femur and tibia discovered in the Lower Eocene Formation near Paris. Q. J. Geol. Soc. 1856, 12, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenciennes, A. Remarques à l’occasion d’une communication de M.Lartet sur le tibia d’oiseau fossile trouvé à Meudon. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Séances L’académie Sci. 1855, 40, 583–584. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, C.W. On the extinct birds of Patagonia. The skull and skeleton of Phororhacos inflatus Ameghino. Geol. Soc. Lond. 1899, 15, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaparte, C. Conspectus in eptorium et struthiorum. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Séances L’académie Sci. 1856, 43, 840–841. [Google Scholar]

- Witmer, L.M.; Rose, K.D. Biomechanics of the jaw apparatus of the giant Eocene bird Diatyrma: Implications for diet and mode of life. Paleobiology 1991, 17, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E.; LeLoeuff, J. A large French Cretaceous bird. Nature 1995, 37, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E.; LeLoeuff, J. A new giant groundbird from the Upper Cretaceous of southern France. J. Geol. Soc. 1998, 155, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E.; Angst, D. New evidence of a giant bird from the Late Cretaceous of France. Geol. Mag. 2013, 150, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angst, D.; Buffetaut, E.; Corral, J.C.; Suberbiola, X.P. First record of the Late Cretaceous giant bird Gargantuavis pholoinos from the Iberian Pennsula. Ann. Paléontologie 2017, 103, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E.; Angst, D.; Mechin, P.; Mechin-Salessy, A. A femur of the giant bird Garganuavis from the Late Cretaceous of Var (south-eastern France). Carnets Nat. 2019, 6, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Puyeo, M.; Puértolas-Pascuel, E.; Moreno-Azana, M.; Cruzado-Cabalerra, P.; Gasca, J.M.; Núnez-Lahnerta, C.; Canudo, J.I. First record of a giant bird (Ornithouromorpha) from the uppermost Maastrichtian of the Southern Pyranees, northeast Spain. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2021, 41, e1900210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.M.; Dawson, M.R. Vertebrate paleontology and the Cenozoic history of the North Atlantic region. Polarforschung 1978, 48, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, L. A new form of the Gastornithidae from the Lower Eocene of the Xuchuan, Honan. Vertebr. Palasiat. 1980, 18, 111–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kay, R.F. 100 years of primate paleontology. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2018, 165, 652–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dughi, R.; Sirugue, F. Sur le fragments decoquilles d’œufs fossils del’Eocène de Basse-Provence. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Séances L’académie Sci. 1959, 249, 959–961. [Google Scholar]

- Dughi, R.; Surgue, F. Distribution vertical des œufs d’piseaux de l’Eocène de Basse-Provence. Bull. Société Géologiquede Fr. 1962, 4, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dughi, R.; Sirgugue, F. Marnes à œuf d’Oiseaux du Paléocene de Basse-Provence. Bull. Société Géologique Fr. 1968, 10, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dughi, R.; Plaziat, J.-C.; Sirugue, F. La repartition stratigraphique des œufs d’oiseaux du groupe d’Oritholithus arcuatus D. et S parrapport aux faunes d’eau douce et marines du Sparnaciener du Thanétien de l’Aude. Compte Rendus Somm. Séancesde Société Géologiquede Fr. 1969, 1, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, D.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Amiot, R.; Smekyala, F.; Giner, S.; Méchin, P.; Amoros, A.; Leroy, L.; Guiomar, M. Fossil avian egg from the Paleogene of southern France: New size estimates and a possible taxonomic identification of the egg-layer. Geol. Mag. 2015, 152, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillers, S.C.; Preez, H.D.; Maritz, J.; Hayes, J.R. Growth curves of ostriches (Struthio camelus) from Oudshorn, in South Africa. Anim. Sci. J. 1995, 61, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunter, K.L.; Schalk, W.P.C. Genetic parameters for egg-chick and live-weight trait recorded in farmed ostriches (Struthiocamelus). Livest. Prod. Sci. 2004, 91, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common Ostrich. Available online: https://ebird.org/species/ostric2 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Cooper, R.G. Growth in the ostrich (Struthio camelus var. domesticus). Anim. Sci. J. 2005, 76, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M.; Worthy, T.H.; Ford, T.; Hoppitt, W.; Willerslev, E.; Drummond, A.; Cooper, A. Extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis. Nature 2003, 425, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

| Racehorse Creek Landslide | Racehorse Creek | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Linear Dimensions in mm; Angles in Degrees) | ||||||||||||

| WWU TR-57 A | WWU TR-57B | WWU TR-58B | WWU TR-58C | WWU TR-59B | WWU TR-66 | WWU-TR-67 | WWU-TR-68 | WWU TR-72 | WWU TR-73 A | WWU TR-73 B | WWU TR-74 A | |

| Width 1 | 245 | 225 | ~230 | ~230 | 265 | 280 | 230 | 225 | * | 285 | 285 | 60 |

| Length 2 | 285 | 262 | 280 | 285 | 245 | 250 | 260 | 285 | 285 | 230 | 260 | 60 |

| Digit II-IV angle | 66 | 67 | 64 | 66 | 84 | 86 | 82 | 80 | 84 | 97 | 102 | 92 |

| Digit III max. width | 48 | 52 | 50 | 48 | 58 | 47 | 50 | 55 | 55 | 95 | 110 | 21 |

| Interdigital angles | 30, 36 | 32, 35 | 32, 32 | 32, 34 | 43, 38 | 48, 38 | 45, 37 | 42, 38 | 42, 42 | 49, 48 | 54, 48 | 43, 49 |

| Length left digit 3 | 239 | 210 | 200 | 220 | 190 | 192 | 190 | 200 | 200 | 70 | 70 | 11 |

| Length right digit 3 | c. 205 | c. 200 | c. 200 | - | 222 | 210 | 195 | 228 | * | 82 | 60 | 11 |

| Heel pad imprint max. depth | 18 | 18 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 32 | 30 | 22 | 12 | ND | ND | ND |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustoe, G.E. Giant Bird Tracks (Family Gastornithidae) from the Paleogene Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington, USA, with a Review of Gastornis Distribution. Foss. Stud. 2025, 3, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3010004

Mustoe GE. Giant Bird Tracks (Family Gastornithidae) from the Paleogene Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington, USA, with a Review of Gastornis Distribution. Fossil Studies. 2025; 3(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustoe, George E. 2025. "Giant Bird Tracks (Family Gastornithidae) from the Paleogene Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington, USA, with a Review of Gastornis Distribution" Fossil Studies 3, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3010004

APA StyleMustoe, G. E. (2025). Giant Bird Tracks (Family Gastornithidae) from the Paleogene Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington, USA, with a Review of Gastornis Distribution. Fossil Studies, 3(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3010004