Promoting Mental Health in Adolescents: “Teens Mental+”, a Nursing Intervention Program Based in the Positive Mental Health Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- To promote adolescent mental health literacy: increase adolescents’ knowledge of what mental health is, the importance of mental health self-care, and what constitutes mental health.

- -

- To promote PMH in middle adolescents aged 12–14 years in educational centers.

- -

- To analyze the effectiveness of a PMH intervention in adolescents’ life satisfaction and psychological well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Target Population

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Measures

- -

- Positive Mental Health Questionnaire by Teresa Lluch (1999) [18]. This scale has been created and validated in its Spanish version. It consists of 39 items scored on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). It has no subscales, providing only an overall score.

- -

- Life Satisfaction Questionnaire (Huebner, 1991) [29] with its Spanish version recently validated by Galíndez and Casas, (2010) [30]. It consists of 7 items scored on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree). It has no subscales, providing only an overall score. There are 3 reverse items: 2, 3 and 4.

- -

- Riff’s Psychological Well-Being Questionnaire (1995) [31], Spanish version by Díaz et al. (2006) [32] and adapted to children and adolescents by Stavraki et al. (2021) [33]. This questionnaire includes 18 items in a total of 6 dimensions that assess self-acceptance, mastery of the environment, positive relationships with others, autonomy, personal growth and life purpose.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Intervention

3. Program Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blakemore, S.-J. Adolescence and Mental Health. Lancet 2019, 393, 2030–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pringle, J.; Mills, K.; McAteer, J.; Jepson, R.; Hogg, E.; Anand, N.; Blakemore, S.-J. A Systematic Review of Adolescent Physiological Development and Its Relationship with Health-Related Behaviour: A Protocol. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santre, S. Mental Health Promotion in Adolescents. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 18, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlack, R.; Peerenboom, N.; Neuperdt, L.; Junker, S.; Beyer, A.-K. The effects of mental health problems in childhood and adolescence in young adults: Results of the KiGGS cohort. Robert Koch-Inst. 2021, 6, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Ren, H.; Cao, R.; Hu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, C.; Mei, S. The Effect of COVID-19 on Youth Mental Health. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nearchou, F.; Flinn, C.; Niland, R.; Subramaniam, S.S.; Hennessy, E. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luengo-González, R.; Noriega-Matanza, M.C.; Espín-Lorite, E.J.; García-Sastre, M.M.; Rodríguez-Rojo, I.C.; Cuesta-Lozano, D.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. The Role of Life Satisfaction in the Association between Problematic Technology Use and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; Bonnie, R.J., Backes, E.P., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Afifi, R.A.; Bearinger, L.H.; Blakemore, S.-J.; Dick, B.; Ezeh, A.C.; Patton, G.C. Adolescence: A Foundation for Future Health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilar, L.; Štiglic, G.; Kmetec, S.; Barr, O.; Pajnkihar, M. Effectiveness of School-based Mental Well-being Interventions among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2023–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Breakdown: A Needed Fourth Step in the Conceptual Armamentarium of Modern Medicine. Soc. Sci. Med. 1972, 6, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moya, I.; Morgan, A. The Utility of Salutogenesis for Guiding Health Promotion: The Case for Young People’s Well-Being. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 32, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, G.F.; Roy, M.; Bakibinga, P.; Contu, P.; Downe, S.; Eriksson, M.; Espnes, G.A.; Jensen, B.B.; Juvinya Canal, D.; Lindström, B.; et al. Future Directions for the Concept of Salutogenesis: A Position Article. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Länsimies, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Hietasola-Husu, S.; Kangasniemi, M. A Systematic Review of Adolescents’ Sense of Coherence and Health. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 31, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Wilson, P.; Marcos-Marcos, J.; Morgan, A.; Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B.; Álvarez-Dardet, C. ‘A Synergy Model of Health’: An Integration of Salutogenesis and the Health Assets Model. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

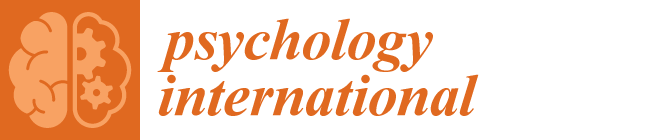

- Iasiello, M.; van Agteren, J.; Cochrane, E.M. Mental Health and/or Mental Illness: A Scoping Review of the Evidence and Implications of the Dual-Continua Model of Mental Health. Evid. Base 2020, 2020, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahoda, M. Current Concepts of Positive Mental Health; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Lluch Canut, M.T. Construcción de una Escala para Evaluar la Salud Mental Positiva; Universidad de Barcelona, Departamento de Metodología de las Ciencias del Comportamiento: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lluch Canut, M.T.; Universitat de Barcelona. Promoción de la salud mental positiva. Rev. Enferm. Salud Ment. 2015, 1, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Mental Illness and/or Mental Health? Investigating Axioms of the Complete State Model of Health. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Mental Health Promotive and Preventive Interventions for Adolescents: Helping Adolescents Thrive; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnsen, H.N.; Espnes, G.A.; Eilertsen, M.-E.B.; Ringdal, R.; Moksnes, U.K. The Relationship between Positive Mental Health Literacy and Mental Well-Being among Adolescents: Implications for School Health Services. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 35, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıdık, G.; Sisman, F.N. School-based mental health programs for improving psychosocial well-being in children and adolescents: Systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 12, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Sequeira, C.; Lluch, T. Programa de Promoción de la Salud Mental Positiva para Adultos (Mentis Plus+): Manual de Apoyo; Universitat de Barcelona, Deposito Digital, Colección OMADO: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, D.; Taylor, A.; Strelan, P. Factors Contributing to the Efficacy of Universal Mental Health and Wellbeing Programs in Secondary Schools: A Systematic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2023, 8, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.M.; Clarke, A.M.; Jenkins, R.; Patel, V. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Mental Health Promotion Interventions for Young People in Low and Middle Income Countries. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, J.; Oliveira, A.P.; Monteiro, F.; Sequeira, C.; Ferré-Grau, C. Promotion of Mental Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S. Initial Development of the Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1991, 12, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galíndez, E.; Casas, F. Adaptación y validación de la Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) con adolescentes. Estud. De Psicol. 2010, 31, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, D.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Blanco, A.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Gallardo, I.; Valle, C.; van Dierendonck, D. Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff [Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBS)]. Psicothema 2006, 18, 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Stavraki, M.; García-Márquez, R.; Bajo, M.; Callejas-Albiñana, A.I.; Paredes, B.; Díaz, D. Brief Version of the Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scales for Children and Adolescents: Evidence of Validity. Psicothema 2022, 34, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velten, J.; Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. Positive Mental Health Scale: Validation and Measurement Invariance across Eight Countries, Genders, and Age Groups. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 34, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.; Casey, L. The Mental Health Literacy Scale (MHLS): A New Scale-Based Measure of Mental Health Literacy. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, C.; Duarte, J.; Sampaio, F.; Coelho, J.; Gonçalves, A.; Santos, V.; Sequeira, C. Construction and Validation of the Positive Mental Health Literacy Assessment Scale in Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Ferré-Grau, C.; Canut, T.L.; Pires, R.; Carvalho, J.C.; Ribeiro, I.; Sequeira, C.; Rodrigues, T.; Sampaio, F.; Costa, T.; et al. Positive Mental Health in University Students and Its Relations with Psychological Vulnerability, Mental Health Literacy, and Sociodemographic Characteristics: A Descriptive Correlational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequeira, C.; Carvalho, J.C.; Gonçalves, A.; Nogueira, M.J.; Lluch-Canut, T.; Roldán-Merino, J. Levels of Positive Mental Health in Portuguese and Spanish Nursing Students. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020, 26, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado-Pardos, B.; Moreno-Arroyo, C.; Casas, I.; Lluch-Canut, T.; Lleixà-Fortuño, M.; Farrés-Tarafa, M.; Roldán-Merino, J. Positive Mental Health and Prevalence of Psychological Ill-Being in University Nursing Professors in Catalonia, Spain. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2017, 55, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factors | Conceptual Aspects |

|---|---|

| F1—Personal Satisfaction | This refers to satisfaction with yourself (self-concept/self-esteem), with your personal life and with your prospects. |

| F2—Prosocial Attitude | It includes a person’s sensitivity to his or her social environment, the attitude and desire to help and/or support others, and the acceptance of others and differential social facts. |

| F3—Self-Control | This is the person’s ability to cope with stress and conflict, emotional stress and conflict, emotional balance/emotional control, and tolerance to anxiety and stress. |

| F4—Autonomy | It includes the ability to make one’s own decisions using one’s own judgement, self-regulating one’s own behavior and maintaining a good level of self-confidence/self-esteem. |

| F5—Problem Solving and Self-Actualization | It refers to a person’s analytical capacity, decision-making skills, as well as their flexibility/ability to adapt to change, developing an attitude of continuous personal growth and development. |

| F6—Interpersonal Relationship Skills | It includes a person’s ability to communicate and establish intimate interpersonal relationships and empathy/ability to understand the feelings of others. It is the ability to offer emotional support. |

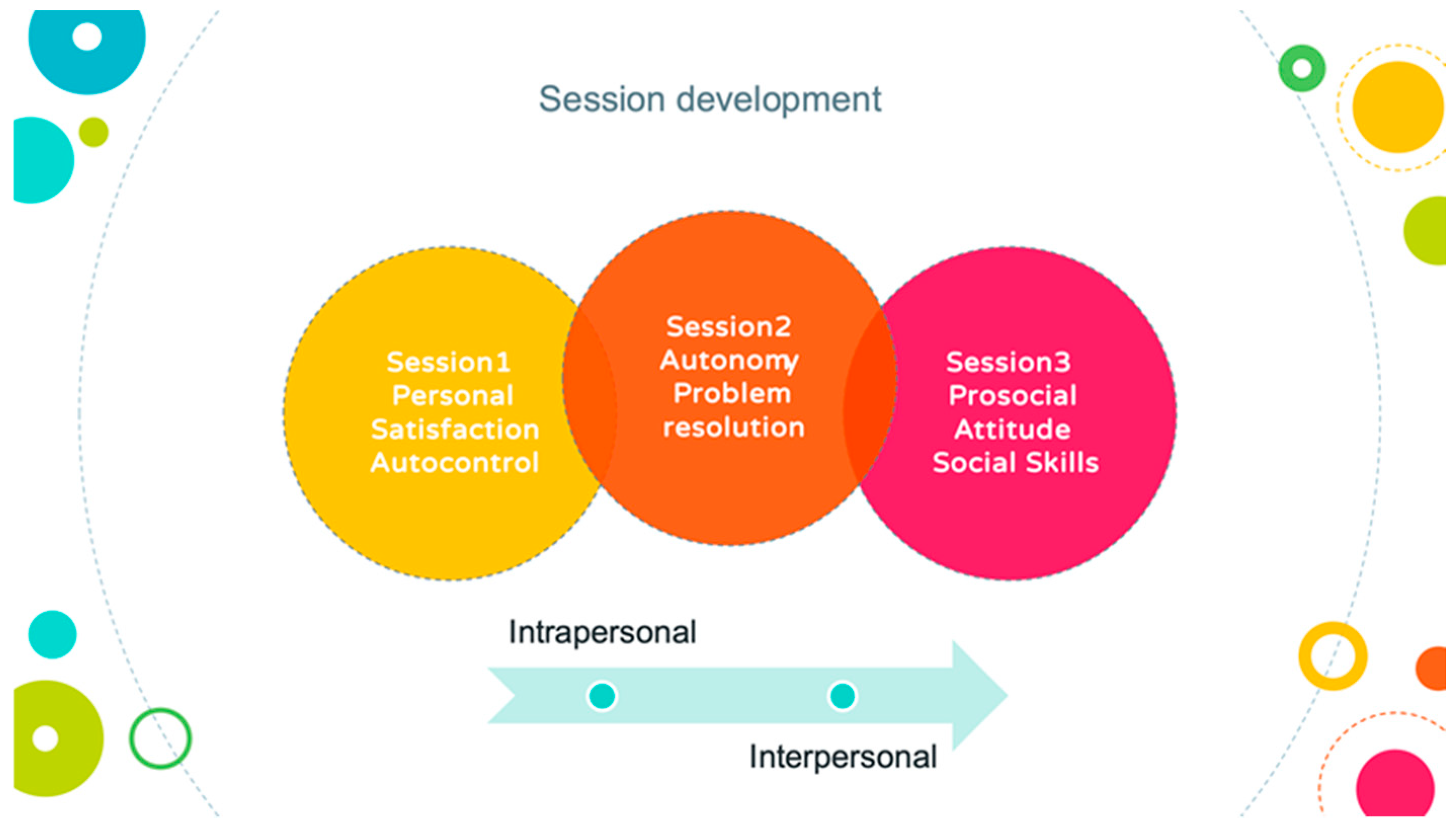

| Session 1: Tips for Feeling OK and Control My KOs | |

|---|---|

Objectives:

| Contents:

|

Resources:

| Activities:

|

Evaluation:

| |

| Session 2: More Capable Than I Think | |

|---|---|

Objectives:

| Contents:

|

Resources:

| Activities:

|

Evaluation:

| |

| Session 3: Be Social and Ask For Help | |

|---|---|

Objectives:

| Contents:

|

Resources:

| Activities:

|

Evaluation:

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Sastre, M.M.; González-Alegre, P.; Luengo-González, R.; Cuesta-Lozano, D.; Rodríguez-Rojo, I.C.; Lluch-Canut, T.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. Promoting Mental Health in Adolescents: “Teens Mental+”, a Nursing Intervention Program Based in the Positive Mental Health Model. Psychol. Int. 2024, 6, 710-721. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint6030044

García-Sastre MM, González-Alegre P, Luengo-González R, Cuesta-Lozano D, Rodríguez-Rojo IC, Lluch-Canut T, Peñacoba-Puente C. Promoting Mental Health in Adolescents: “Teens Mental+”, a Nursing Intervention Program Based in the Positive Mental Health Model. Psychology International. 2024; 6(3):710-721. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint6030044

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Sastre, María Montserrat, Patricia González-Alegre, Raquel Luengo-González, Daniel Cuesta-Lozano, Inmaculada Concepción Rodríguez-Rojo, Teresa Lluch-Canut, and Cecilia Peñacoba-Puente. 2024. "Promoting Mental Health in Adolescents: “Teens Mental+”, a Nursing Intervention Program Based in the Positive Mental Health Model" Psychology International 6, no. 3: 710-721. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint6030044