Can Indigenous Knowledge Contribute to the Sustainability Management of the Aspiring Rio Coco Geopark, Nicaragua?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Process

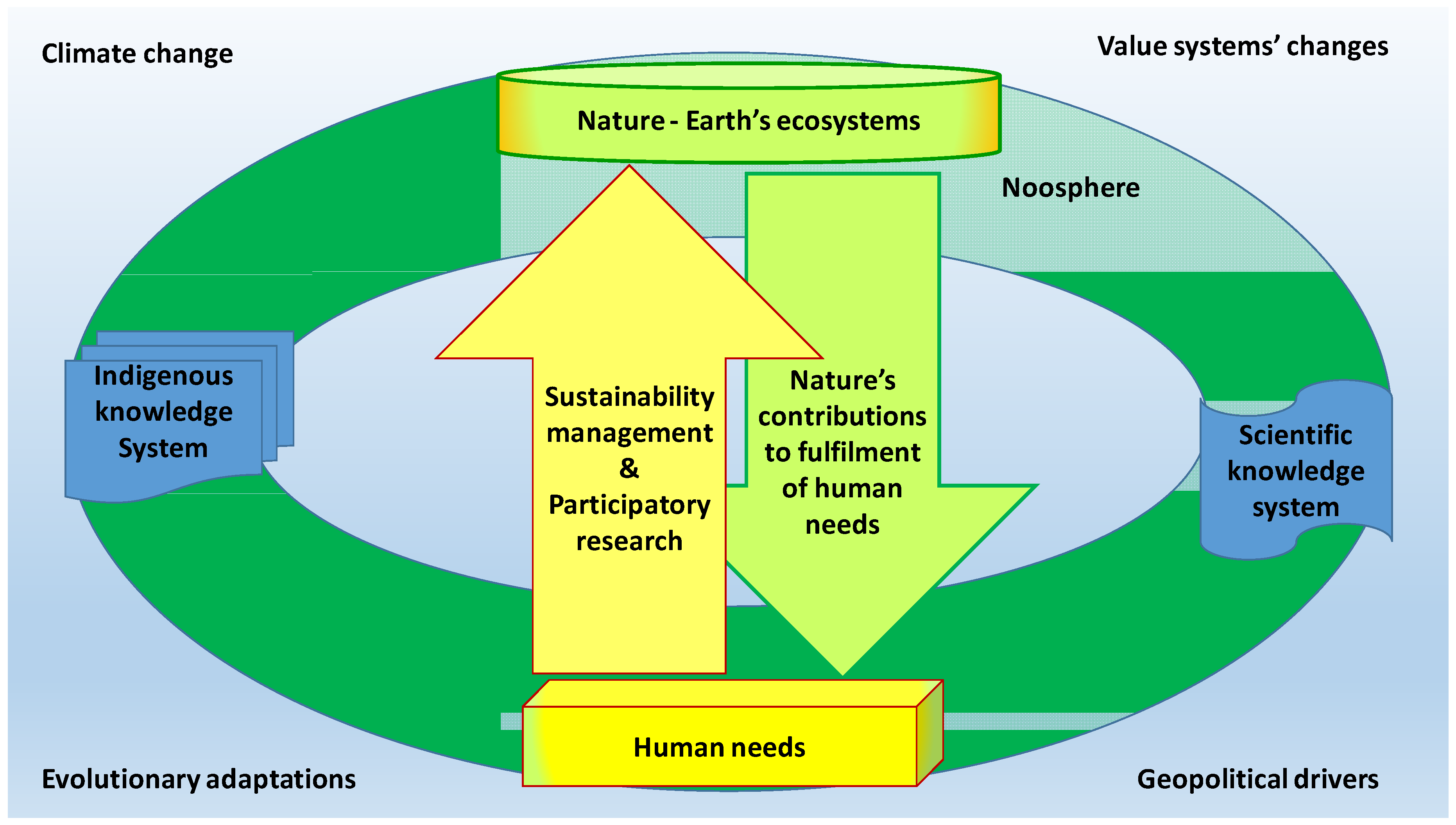

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Indigenous Konwledge and Meanings

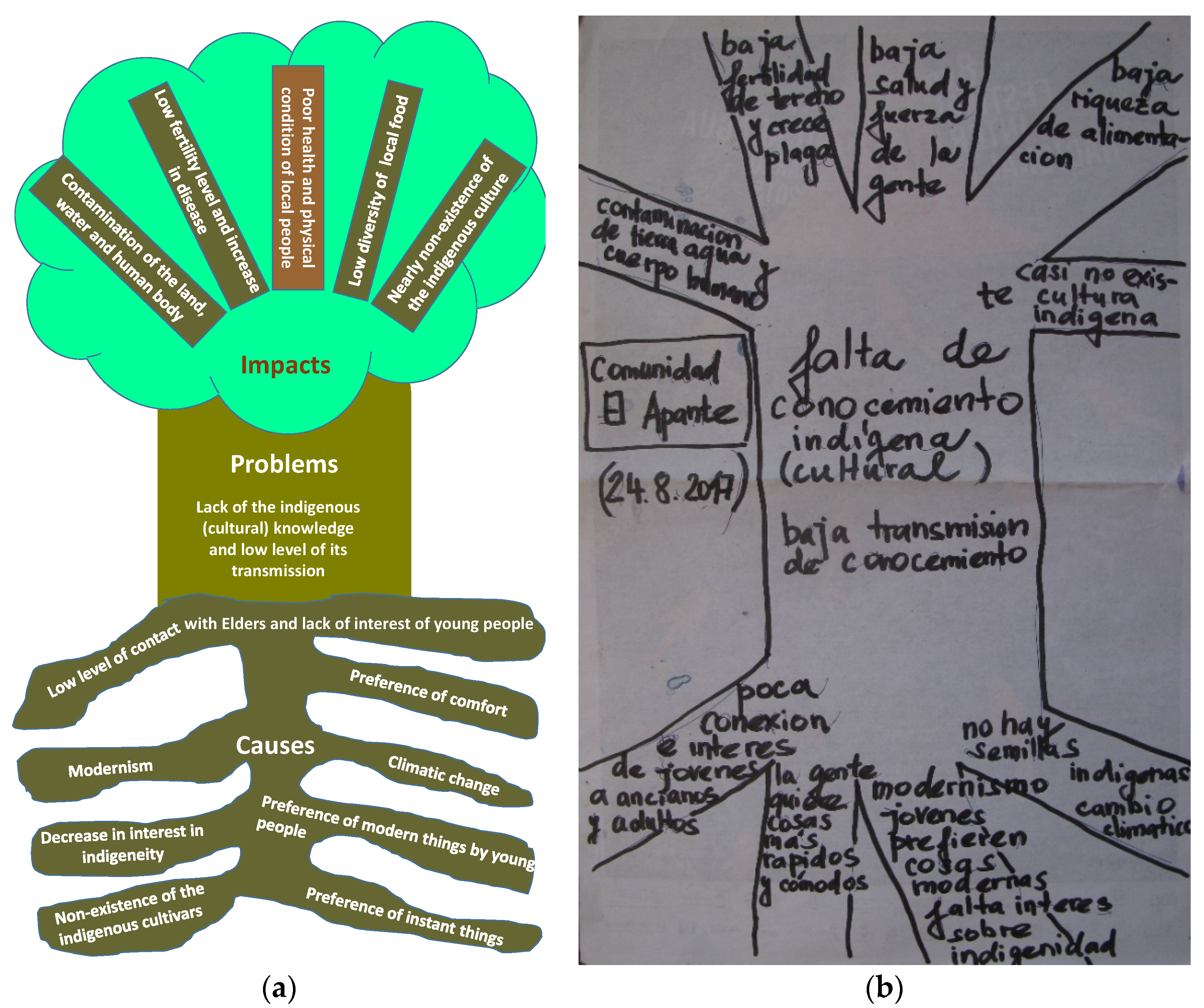

3.2. Problems Related to Local Sustainability Management Identified by Local Indigenous People

3.3. Indigenous Knowledge Potential for the Sustainability Management of the Geopark and Its Geotourism

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Sustainability, Maintanance, Transmission and Documentation of the Indigenous Knowledge

4.2. Implementation of the Potential of the Indigenous Knowledge for the Aspiring Geopark Sustainability

4.3. Recommendation for the Aspiring Geopark Management and Future Research

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pásková, M.; Zelenka, J. Social responsibility role in tourism sustainability. In Proceedings of the Hradec Economic Days; Jedlička, P., Ed.; Gaudeamus: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Starik, M.; Kanashiro, P. Toward a theory of sustainability management: Uncovering and integrating the nearly obvious. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J.; Freeman, R.E.; Schaltegger, S. Applying stakeholder theory in sustainability management. Links, similarities, dissimilarities, and a conceptual framework. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.F.; Menzies, C.R. Traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous tourism. In Tourism and Indigenous Peoples; Butler, R., Hinch, T., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.; Ruhanen, L.; Whitford, M. Indigenous peoples and tourism: the challenges and opportunities for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Espeso-Molinero, P. Collaborative capacity building as a resilience strategy for tourism development in indigenous Mexico. In Tourism, Resilience, and Sustainability: Adapting to Social, Political and Economic Change; Cheer, J., Lew, A.A., Eds.; Routledge: Tranmere, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Farsani, N.T.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C. Geotourism and geoparks as gateways to socio-cultural sustainability in Qeshm Rural Areas, Iran. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M. Local and indigenous knowledge regarding the land use and use of other natural resources in the aspiring Rio Coco geopark. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Prague, The Czech Republic, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M. The potential of indigenous knowledge for Rio Coco Geopark Geotourism. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 15, 886–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M.; Hradecký, P. Aspiring Geopark Rio Coco (Nicaragua). In Proceedings of the SGEM Conference Proceedings, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pásková, M.; Dowling, R.K. The usage of local and indigenous knowledge in the management of geotourism destinations. In Proceedings of the SGEM Conference Proceedings, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.K. Global geotourism—An emerging form of sustainable tourism. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, D.; Roué, M. Indigenous knowledge, peoples and sustainable practice. In Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change; Timmerman, P., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guchteneire, P.; Krukkert, I.; Liebenstein, G. Best Practices on Indigenous Knowledge; Bowen, K., Morohashi, J., Eds.; Nuffic: Tha Hague, The Netherlands; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Roué, M.; Nakashima, D. Knowledge and foresight: The predictive capacity of traditional knowledge applied to environmental assessment. Intern. Soc. Sci. J. 2002, 54, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Learning and Knowing in Indigenous Societies Today; Bates, P., Chiba, M., Kube, S., Nakashima, D., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, V. Indigenous peoples and biodiversity. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity; Levin, S.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, A.; Parellada, A.; Newing, H. Indigenous peoples and biodiversity conservation in Latin America: From principles to practice. In Proceedings of the Pucallpa Conference; IWGIA Document No. 87; IWGIA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mallarach, J.M. Protected Landscapes and Cultural and Spiritual Values. Values of Protected Landscapes and Seascapes Series No. 2; Kasparek Verlag on behalf of IUCN, GTZ and Social de Caixa Obra Catalunya: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth, K.; Cronin, S.J. Volcanic structures and oral traditions of volcanism of Western Samoa (SW Pacific) and their implications for hazard education. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2009, 186, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.V.; Cronin, S.J. Welcoming a monster to the world: Myths, oral tradition, and modern societal response to volcanic disasters. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2008, 176, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henige, D. Can a myth be astronomically dated? (Iroquois League, oral tradition, solar eclipse). Am. Indian Cult. Res. J. 1999, 23, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, M. Oral traditions or situated practices? Understanding how indigenous communities respond to environmental disasters. Hum. Organ. 2012, 71, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-Prieto, J.L.; Rosado-González, E.; Ramírez-Miguel, X.; Oropeza-Orozco, O.; Cram-Heydrich, S.; Ortiz-Pérez, M.A.; Figueroa-Mah-Eng, J.M.; de Castro-Martínez, G.F. Erosion, culture and geoheritage; the case of Santo Domingo Yanhuitlan, Oaxaca, Mexico. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, D.W.; Catchpole, A.J.W.; Abel, K. Northern Athapaskan Oral traditions and the White River Volcano. Ethnohistory 1992, 39, 148–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fepuleai, A.; Weber, E.; Németh, K.; Muliaina, T.; Iese, V. Eruption styles of Samoan volcanoes represented in tattooing, language and cultural activities of the indigenous people. Geoheritage 2017, 9, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, P.M.; Frithz, N.M. Conocimientos del Pueblo Mayangna Sobre la Convivencia del Hombre y la Naturaleza. Peces y Tortugas Tomo 1; UNESCO Office: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gros, P.M.; Frithz, N.M. Conocimientos del Pueblo Mayangna Sobre la Convivencia del Hombre y la Naturaleza. Peces y Tortugas Tomo 2; UNESCO Office: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Colding, J.; Folke, C.; Elmqvist, T. Social institutions in ecosystem management and biodiversity conservation. Trop. Ecol. 2003, 44, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Samakov, A. Sacred Sites: Opportunity for Improving Biocultural Conservation and Governance in Ysyk-Köl Biosphere Reserve, Kyrgyz Republic. Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klubnikin, K.; Annett, C.; Cherkasova, M.; Shishin, M.; Fotieva, I. The sacred and the scientific: Traditional ecological knowledge in Siberian river conservation. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1296–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, V. Manual de Investigación Cultural Comunitaria: Herramientas Cultura y Desarrollo 1; UNESCO Office: San José, Costa Rica, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kassam, K.-A.S.; Graham, J.R. Indigenous knowledge, community participation, and traditional land use mapping. In Social Work & Aboriginal Peoples: Perspectives from Canada’s Rural and Provincial Norths; Brownlee, K., Neckoway, R., Delaney, R., Durst, D., Eds.; Lakehead University, Center for Northern Studies: Thunder Bay, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gratani, M.; Bohensky, E.L.; Butler, J.R.A.; Sutton, S.G.; Foale, S. Experts’ Perspectives on the Integration of Indigenous Knowledge and Science in Wet Tropics Natural Resource Management. Aust. Geogr. 2014, 45, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, S.J.; Gaylord, D.R.; Charley, D.; Alloway, B.V.; Wallez, S.; Esau, J.W. Participatory methods of incorporating scientific with traditional knowledge for volcanic hazard management on Ambae Island, Vanuatu. Bull. Volcanol. 2004, 66, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, S.B. Indigenous knowledge of biological resources and intellectual property rights: The role of anthropology. Am. Anthropol. 1993, 95, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, G.W. Traditional ecological knowledge and Inuit: Reflections on TEK research and ethics. Arctic 1999, 52, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, J.; Phillips, A. Indigenous and Traditional Peoples and Protected Areas. Principles, Guidelines and Case Studies; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK; WWF International: Gland, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Simonič, P. Etnography of Protected Areas. Engangered Habitats—Engangered Cultures; University of Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Kothari, A.; Oviedo, G. Indigenous and Local Communities and Protected Areas. Towards Equity and Enhanced Conservation Guidance on policy and practice for Co-managed Protected Areas and Community Conserved Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wiliamson, M.; Mendoza, M.J.; Valerio, L.; Garcia, R.; del Cid, V.; Mendoza, J.; Castro, W.; Salas, R. Pueblos Originarios y Afrodescendientes de Nicaragua Etnografía, Ecosistemas Naturales y Áreas Protegidas; IBIS-Education for development: Hong Kong, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Global Geoparks. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/earth-sciences/unesco-global-geoparks/top-10-focus-areas/ (accessed on 2 May 2018).

- Dosier de Candidatura del Proyecto de Geoparque Río Coco; Archive of the Somoto Town Hall; Alcaldía de Somoto: Somoto, Nicaragua, 2017.

- Barth, F. An anthropology of knowledge. Curr. Anthropol. 2002, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Gregory, D.; Pratt, G.; Watts, M. The Dictionary of Human Geography, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Semple, E.C.; Ratzel, F. Influences of Geographic Environment, on the Basis of Ratzel’s System of Anthropo-Geography; H. Holt and Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Plan de Manejo Reserva Natural Serranía Tepesomoto y Pataste; Ministerio del Ambiente y los Recursos Naturales; MARENA: Managua, Nicaragua, 2008.

- Navarro-Genie, R. (Eveha Nicaragua, Managua, Nicaragua). Personal communication, 2018.

- Werner, P.S. Ethnohistory of the Early Nicaragua. Demography and Encomiendas of Communities; Occasional Publication No. 4; Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, The University at Albany: Albany, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Nicaragüense para el Desarrollo Sostenible FUNDENIC—SOS. Evaluación y Redefinición del Sistema de Áreas Protegidas Serranía de Tepesomoto-Pataste de las Regiones Pacífico y Centro Norte de Nicaragua. MARENA—PROTIERRA—CBA. Informe Final, 1–30 2000. Available online: http://www.bvsde.org.ni/Web_textos/MARENA/MARENA0217/EvalRedSistAreasProtSerraniaTepesomoto_%20Pataste.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2018).

- Diagnostico Socioeconomico Subcuenca Rio Tapacalí, Madriz; Archive of the San José de Cusmapa Town Hal; Alianza por la Resiliencia: San José de Cusmapa, Nicaragua, 2014.

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, J.; Corbin, A. Basics of Qualitative Research. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto-Dillon, L. Problem Tree Analysis, 2018 Sustainable Sanitation and Water Management Toolbox. Available online: https://www.sswm.info/planning-and-programming/decision-making/situation-and-problem-analysis/problem-tree-analysis (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Conradin, K. Ecological Sanitation in the Khuvsgul Area, Northern Mongolia: Socio-Cultural Parameters and Acceptance. Master’s Thesis, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E.; Brilha, J. Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.; Aicken, M. Indigenous Tourism. The Commodification and Management of Culture; Routledge: Tranmere, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pásková, M. Negative impacts of tourism and sustainable tourism as an alternative for regional development. In Proceedings of the 3rd Moravian Geographical Conference CONGEO’99, Regional Prosperity and Sustainability, Slavkov u Brna, Czech Republic, 6–10 September 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Research Topics | Research Questions |

|---|---|

| Indigenous land ownership | Is it possible to commercialize the indigenous land? Is the private ownership of the indigenous land possible? How is the indigenous land marked in terrain and how it is documented? |

| The traditional use of the stones and earth | How do you use different types of local stones? How do you use different types of local earth/clay? How long does the construction of your house last and which material do you use? |

| The traditional land use | Where and how large is your plot? Which kind of crops do you cultivate there? Do you rotate your crops? Do you use any fertilizers? Do you combine farming with forestry? Which techniques do you use to manage pest control? Which techniques do you use to prevent erosion? |

| Land conservation | What does the term “Mother Earth” mean to you? Do you follow/respect some natural processes when using the natural resources? Does the local indigenous authority cooperate with the state nature conservation? Have you noticed some significant changes in the local environment, in the quality and/or abundance of water, soil, forests, plants, animals etc.? |

| Indigeneity | What does it mean to you to be an indigenous person? What is specific about the indigenous person, how (s)he differs from the persons representing the dominant “colón” society (e.g., physiognomy, mentality, behaviour, system of values, perception of nature and universe, time and space, death and birth)? Which kind of practices and knowledge are principal for the indigenous identity? What do you know about the origin of your indigenous community, about your ancestors? |

| Education and transmission of knowledge | Are the indigenous knowledge and practices transmitted to the younger generation? Do you perceive the changes in the form of transmission? Do you perceive any effects of these changes on the indigenous identity and on the relation of local people to their land? |

| Position of Elders in the community | How do the Elders influence the decision-making processes of the community? How do the Elders influence the decision-making processes of the family? |

| Nature related spirituality in the daily practice, cosmology | How do you relate to the plants, animals, stones, water and universe? Do you observe the Moon‘s movement and other natural processes? How do you use it for the timing indication in your daily life practice such as farming, forestry, house construction, dating, etc.? |

| Health, natural medicine | Do you collect some medicinal plants? Where do you collect them, is their abundance changing? Which ones and how do you use them? Do you perceive any changes in use of these plants; are the young people still interested in their use? |

| Customs, cuisine | Do you use some plants for cooking? Which plants, which parts of them and how? Do you collect them in the environs of your house or does your family cultivate them? |

| Local sights and legends | Which sites or natural phenomena of El Apante environs are of foremost importance for the local indigenous community? Why? Do you know some legend, myth or true story related to these sites or phenomena? |

| Geopark | Have you heard about the Rio Coco Geopark project? What does it mean to you (“Earth park”), what do you expect from this initiative? |

| Geotourism | What do you think about possibility of sharing your house for some days with some traveller? Would it be interesting for you? Would it be possible to share your knowledge and your time with him/her, and to let them eat and work with your family? |

| Research Locality | Applied Methods | Examples of the Observed Indigenous Knowledge | Illustrative Photography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household of Don Arcadio (77 years) and Doña Juana (76 years) Sector I (Sector Central) 840 m a.s.l. |

|

|  The “Malanga” washed on the stone  The fresh bark of the quebracho tree  Tortillas production as a daily routine  Lunar periodicity is at the core of indigenous cosmology |

| Household of Doña Rosa (73 years) Sector I (Sector Central) 857 m a.s.l. |

|

|  Ancient millstone found in El Apante surroundings, still used by Doña Rosa for crushing of coffee and corn |

| Household of Don Anatolín (79 years) Sector I (Sector Central) 870 m a.s.l. |

|

|  Don Anatolín (above) explains how to elaborate the “argana” bag (bellow)  |

| Household of Doña Santos (70 years) Sector II Ojo de agua 899 m a.s.l. |

|

| The stove made of the nearby clay |

| Household of Don José (45 years) Sector II Ojo de agua 910 m a.s.l. |

|

|  Natural bowls for beans, other “basic grains” and corn pancakes  |

| Household of Don José (84 years) Sector III Mangas Verdes (Geosite of aspiring Rio Coco Geopark) 1003 m a.s.l. |

|

|  The palm leaves still serve for production of bags, mats and baskets  |

| Household of Don Getrudo (53 years) Sector IV Marañon 954 m a.s.l. |

|

|  Eroded volcanic stone used as a manager for domestic animals and “ladrillos” prepared for burning  |

| Household of José (46 years) Cave near to El Arenal hill 798 m a.s.l. |

| The cave hidden at the foot of the El Arenal hill located near to the departmental border (between Madriz and Estelí) used as a house by the local family. Don José continues living there with his wife and three children as did his father. He expressed his happiness with their simple, but peaceful, undisturbed natural living environment, having the solid “roof” above his head, fresh water stemming from local spring and food provided directly by the “Mother Earth”. He cultivates beans and corn. |  Cave used for living by local family  |

| Indigenous house (“casa cultural” or “Casa Indígena”) Sector I 870 m a.s.l. |

|

|  Corn as a base of local diet (e.g., “atol” pudding) represents a fertility symbol  |

| Piedra Orocuina rock (Geosite of aspiring Rio Coco Geopark, near to the road to San José de Cusmapa) 1209 m a.s.l. |

| In the environs of this Tertiary volcanic formation, local archaeologists accompanied by the author discovered ancient pieces of ceramics and chiselled lithic material (mainly obsidian and flint) which indicates an indigenous ancestral settlement with possible ritual practices. Local inhabitants narrate legends related to the Piedra Orucuina, e.g., about three small houses (in reality large stones), they also relate about settlement of ancient peoples who had migrated from Guatemala and Honduras and they related that all rivers spring there. |  Piedra Orocuina, connected with indigenous legends, is hiding ancient ceramic and lithic relicts at its foot. These sites are archaeologically under-researched.  |

| The Indigenous Knowledge | Potential for the Sustainability Management of the Aspiring Geopark and Its Geotourism | Causal Conditions of the Potential Implementation and Intervening Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Use of stone, earth, plants and other natural resources for construction of houses, walls, and stoves, as manager, washboard, millstone, pestle, for production of furniture, dishes, baskets, sacks, bags, mats, etc. | Prevention of the soil, water and air contamination of the geopark territory through increased use of the natural recyclable materials, increase in the geotourism diversity through participatory interpretation of the use of the local volcanic stones and other natural materials | Systematic public education in geopark territory involving values system change, which can relieve the factors as market economy drivers, excessive demand for comfort and modernity, is needed. |

| “Family farming” mainly for auto-consumption, without any fertilizers (or just with organic ones), practice of agroforestry system (especially silvopastoral) and rotation system, using the ”dead barriers” and “living fences”, diverse composition of crops, the use of the local both cultivated and wild plants for cooking | Contamination prevention of the human body and local environment (caused by chemical preservatives and fertilizers, transport emissions, etc.) through an increased level of implementation of the organic, small size farming, agroforestry system, increase in the geotourism diversity through the participatory geo-gastronomic programs with use of local crops, plants and herbs including the interpretation of soil composition and characteristics | The rights of indigenous communities on their indigenous lands must no longer be violated. The organic, diversified “family farming” must be preferred to the large monocultural farming with chemical treatment. The visitors’ fear of the quality of the local hygiene should be relieved. |

| Local indigenous identity based on the connection to “Mother Earth” as basis of life | More holistic approach to conservation and interpretation of Earth heritage—an increased stress on the interconnection between the natural and spiritual values of the Earth heritage, increased geotourism authenticity through the participation of local indigenous geoguides and georangers | The conservative approach to nature conservation, strictly separating the science and culture, should be avoided; the acceptance of coexistence of the different, indigenous value system is needed. Local indigenous people must have opportunities for education concerning the local geology, ecology, archaeology and anthropology. |

| The position of Elders in the decision-making processes and mentoring | Involvement of voices of wisdom through engagement of Elders and women into the decision-making processes of geopark management, since they have proved to have higher level of indigenous knowledge | The consultation with “Consejos de Ancianos” (Councils of Elders) must be incorporated into the decision-making processes of the aspiring geopark management. |

| Spirituality and cosmology related to the land use and use of other natural resources, use of lunar methodologies enhancing the respect for cyclic natural processes | Implementation of the carrying capacity concept in Earth heritage conservation through observing the rhythm of local natural processes (leaving some time and space for recuperation of ecosystems and their various elements) | The public mistrust of spiritually based knowledge and conservative approach to nature conservation, strictly separating the science and culture, must be avoided. |

| Transmission of indigenous knowledge, practices and legends | An increase in the geotourism diversity and authenticity—a challenge for local geoguiding system with use of local indigenous knowledge including legends, myths and stories | The traditional intergenerational oral face-to-face communication must be supported. The system of education for local geoguides and Earth heritage interpretation must be prepared. |

| The use of medicinal plants and indigenous healing techniques | An improvement of the health and related knowledge of the geopark population, increase in the geotourism diversity through participatory geo-medical and geo-meditative programs with use of knowledge of the local plants and related specific soil characteristics | The conservative approach and prejudices to the “natural medicine” should be avoided. Local indigenous people must have opportunities for education concerning the local botany, ecology and anthropology. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pásková, M. Can Indigenous Knowledge Contribute to the Sustainability Management of the Aspiring Rio Coco Geopark, Nicaragua? Geosciences 2018, 8, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8080277

Pásková M. Can Indigenous Knowledge Contribute to the Sustainability Management of the Aspiring Rio Coco Geopark, Nicaragua? Geosciences. 2018; 8(8):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8080277

Chicago/Turabian StylePásková, Martina. 2018. "Can Indigenous Knowledge Contribute to the Sustainability Management of the Aspiring Rio Coco Geopark, Nicaragua?" Geosciences 8, no. 8: 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8080277

APA StylePásková, M. (2018). Can Indigenous Knowledge Contribute to the Sustainability Management of the Aspiring Rio Coco Geopark, Nicaragua? Geosciences, 8(8), 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8080277