3. Results

While it is difficult to present quantitative analysis on the problem, we try to discuss the results qualitatively, aiming for technological precision and quantitative assessment only where possible (e.g., in the case of written codes, data and specific information). The full data set (including codes, queries and responses) is available in

Supplementary Materials, which might be necessary for full assessment by the reader, as the full query text inclusion would boast the paper significantly.

Supplementary Materials availability is highlighted in the papers “

Supplementary Materials” and “Data Availability Statement” section.

3.1. General Questions Regarding Building a Smart Home Application, Specification of a Controller

In the first step, we asked ChatGPT which controller we should use for developing a smart home application.

ChatGPT: “Sure! There are several options for micro-controllers that you can choose from for your smart home project. Here are 6 examples from different manufacturers:

Arduino Uno: This is a popular micro-controller board that is easy to use and has a large community. It has 14 digital input/output pins, 6 analog inputs and a 16 MHz quartz crystal.

Raspberry Pi: This is a small, affordable computer that can run a full operating system. It has a variety of input/output options, including GPIO pins, USB ports and Ethernet.

ESP32: This is a powerful micro-controller with built-in Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity. It has 34 GPIO pins, 18 analog inputs and a dual-core processor.

STM32F4 Discovery: This is a development board based on the STM32F407VGT6 micro-controller. It has 168 MHz Cortex-M4 CPU, 1 MB Flash memory, and 192 KB RAM.

PIC18F4520: This is a popular micro-controller from Microchip Technology. It has 32 KB Flash memory, 1.5 KB RAM and 36 I/O pins.

NXP LPC1768: This is a micro-controller based on the ARM Cortex-M3 architecture. It has 512 KB Flash memory, 64 KB RAM and a variety of input/output options.

These are just a few examples, and there are many other micro-controllers available on the market. You will need to choose the one that best fits your project’s requirements in terms of processing power, memory and input/output options.”

At this point, we asked ChatGPT to give arguments on choosing a device.

ChatGPT: “Sure! Here are some arguments for choosing each of the micro-controllers I listed:

Arduino Uno: The Arduino Uno is a popular choice for beginners and hobbyists because it is easy to use and has a large community. There are many tutorials and examples available online, making it easy to get started. It has a simple programming environment and is compatible with a wide variety of sensors and shields.

Raspberry Pi: The Raspberry Pi is a powerful micro-controller that can run a full operating system, making it suitable for more complex projects. It has a variety of input/output options, including GPIO pins, USB ports and Ethernet, making it versatile and flexible. It can also run software like Python, making it easy to integrate with other tools and services.

ESP32: The ESP32 is a powerful micro-controller with built-in Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity. This makes it ideal for projects that require wireless communication, such as remote control or monitoring. It has a large number of input/output pins and a dual-core processor, making it suitable for projects that require a lot of processing power.

STM32F4 Discovery: The STM32F4 Discovery is a development board that is based on the STM32F407VGT6 micro-controller. It has a high processing speed and a large amount of memory, making it suitable for complex projects. It also has a wide range of input/output options, including USB, Ethernet and audio.

PIC18F4520: The PIC18F4520 is a popular micro-controller from Microchip Technology. It has a relatively low cost and a large number of input/output pins, making it ideal for projects that require a lot of sensors or actuators. It also has a large community and many examples available online, making it easy to get started.

NXP LPC1768: The NXP LPC1768 is a micro-controller based on the ARM Cortex-M3 architecture. It has a large amount of memory and a variety of input/output options, making it suitable for a wide range of projects. It also has a powerful processor and can run at high speeds, making it ideal for projects that require fast processing.

In summary, each of these micro-controllers has its own strengths and weaknesses, and the best one for your project will depend on your specific requirements. Factors to consider when choosing a micro-controller include processing power, memory, input/output options and community support.”

We can say, that the information is accurate, and the bot was giving logical arguments with precise information on this very general initial case.

To narrow down the focus, we gave Arduino or Raspberry Pi as a choice. Early investigations showed that the answers give a broader point of view at the beginning of a query-set, so a narrowed approach is beneficial for a start. The bot was able to distinguish the two different systems, with reasonable responses on the general overview regarding the two systems capabilities. It gave advantages and disadvantages about the use.

ChatGPT: “Both the Arduino and Raspberry Pi controllers have their advantages and disadvantages when it comes to building a smart home.

Arduino is a microcontroller board that is designed for simple projects that require low power and have limited processing requirements. It is a good choice if you want to control simple sensors such as temperature, humidity and light sensors. Arduino is easy to use and is ideal for beginners who are starting to learn about microcontrollers.

On the other hand, Raspberry Pi is a small computer that is capable of running a full operating system. It is more powerful than Arduino and has a wider range of capabilities. Raspberry Pi is a better choice if you want to integrate complex sensors such as cameras, voice recognition and machine learning. It also has the capability of connecting to the internet, which allows for remote control and monitoring of your smart home devices.

Therefore, the choice of controller depends on the complexity of your project and the sensors you want to integrate. If you are building a simple smart home system, then an Arduino controller would suffice. However, if you want to build a more advanced system that requires complex sensors and internet connectivity, then Raspberry Pi would be a better choice.”

We found that the answer contained some correct information; however, some other information can be argued with. The discussion did not go to the level of more recent advances of the systems. Arduino also offers newer devices (Portenta family [

24], established in 2020) for higher-level tasks with similar capabilities to the Raspberry lineup. This information was either omitted by the timely limit of the background training data for ChatGPT 3.5 or by the fact that ChatGPT is orienting its answers towards the more common knowledge established over a longer period. According to Hernando, the origins of Arduino can be traced back to 2003–2005 [

25], so the answer given by the bot was a more superficial assumption based on a longer-term general knowledge. The final conclusion of ChatGPT was found to be acceptable; most of the information was valid; and it could argue along a wide range of commercially available products without obvious bias towards one or the other.

3.2. Sensors and Specifications

We also asked for specific types of sensors, where the bot suggested temperature, light, motion, humidity, gas, water and smoke sensors and their combinations with short descriptions, which helps accessibility to the topic even at a beginner level. We emphasize again that, for full analysis, the reading of

Supplementary Materials is recommended.

While the scope would be too wide for analyzing all types, we focused first on temperature sensors. ChatGPT suggested five “popular” alternatives: DHT11, DHT22, LM35, DS18B20 and BME280. It provided short descriptions for each type in its answer. Each component is valid and widely used by hobbyists and professionals in the field. The query followed with light sensors. ChatGPT gave a mix of the types (e.g., photoresistors, photodiodes, phototransistors) and specific sensor modules (e.g., TSL2561, BH1740) in its five-step answer. To sum up, the bot was mixing types and specific commercial components in the answer, which is inconsistent in its manner.

Altogether, from two questions on “specific light sensors” and “specific light sensor models”, the bot listed six components and three type descriptions (with a repeated description on photoresistors). It was clear that slightly different queries affected the answer inconsistency, but the effect seemed rather minor and seemed to be originated from the randomness of each individual answer by the bot. Again, the bot was mixing types and components.

As for motion sensors, five examples were listed. The listing was presented in a third format, where the declared type was followed with a specific component name as well. (e.g., PIR Motion Sensor (HC-SR501)). However, inconsistencies were found, as for five different types, only three actual sensor components were listed, the rest was again general listing. The bot did not provide a real module for infrared motion sensors and laser motion sensors. The same mixed listing was found in the case of humidity sensors. Albeit the bot could give five actual sensor types this time, only one type was specified on its working principle (capacitive humidity sensor (SY-HS-220). Gas, water level and smoke detectors were also sorted by incoherent listing; however, all types were found to be commercially available.

ChatGPT was also asked to list the sensors by price, the bot was able to find ranges of the price, and it arranged a list based on the prices. The ranges seemed valid according to a manual search in popular web shops on the internet. All information seemed to be coherent with current availability for 10 components, but actual prices varied a bit (at the same or one range lower as the current prices). This might not only be due to the recent increase in prices—some components were inconsistently cheaper or more expensive in the list.

The bot suggested Arduino for the project previously, so the follow-up was coherently provided according to this controller type. In short, ChatGPT could carry forward the information precisely from question to question.

After the more general queries on sensors, we asked to suggest specific data for three different sensors. One query focused on the DHT11. The following specifications were given.

ChatGPT: “Here are the specifications of the DHT11 temperature and humidity sensor:

Temperature measurement range: 0 to 50 degrees Celsius with an accuracy of +/−2 degrees Celsius

Humidity measurement range: 20% to 90% RH (Relative Humidity) with an accuracy of +/−5%

Operating voltage: 3.3 V to 5 V DC

Current consumption: 2.5 mA max during conversion, 0.5 mA standby

Signal transmission distance: Up to 20 m

Sampling rate: 1 Hz (1 reading per second)

Response time: less than 5 s

Dimensions: 23 mm × 12 mm × 5 mm (L × W × H)

Digital output: Data is transmitted using a single-wire serial interface with a timing protocol that includes a start signal, data bits, and a checksum for error checking.

The DHT11 sensor is a low-cost, basic temperature and humidity sensor that is suitable for many simple projects. However, if you require higher accuracy, faster response time, or other features, you may need to consider a more advanced sensor.”

The bot was able to summarize the applicability of the sensor in an efficient manner, but a mistake was found. The response time was not accurate. The datasheet gives 6 s minimum, 10 s typical and 15 s max for this parameter [

26], compared to the bot’s version of “less than 5 s”. It was suggested that DHT11 has different datasheets available on the web, but an alternative, widely available datasheet version was also backing up our finding with precise response time values [

27]. We asked the same question for DS18B20 sensor too

Supplementary Materials, where we found that the maximum of the current draw was imprecise for the suggestions (1 mA suggested value vs. 1.5 mA in real life). For two other sensors (TLS2561, MQ-135), the operating voltages, active power consumption and operating temperatures were imprecise (for full details, see

Supplementary Materials), in the meanwhile, staying in similar range as the datasheet values. For TLS2561, ChatGPT gave an “Operating voltage range of: 2.7 V to 3.6V DC”, which is actually 0 V to 3.8 V according to datasheet [

28]. It was found that the “2.7 V to 3.6 V DC” was received from an application note [

29], where the “voltage range” noting is similarly confusing as it is missing the lower boundary of the range. For MQ.135: ChatGPT gave “Operating temperature: −10 to 50 °C”, which is actually max. 45 °C [

30].

Overall, this information can be crucial during design, so while ChatGPT can focus its interest on specific components, many details need validation by human hand. It is suggested that the bot was trained on older data or misleading information was found in the training dataset. Altogether it can be concluded that most of the given data were usable though some responses contained imprecise information in similar, easily confusing or deceiving range as original values found in technical specifications.

3.3. Workflow and Code

To aid embedded coding, ChatGPT was asked how to connect a DS18B20 temperature sensor to the Arduino [

31]. The component was chosen randomly from the previous set of results discussed in

Section 3.2. The answer was the following.

ChatGPT: “To connect a DS18B20 temperature sensor to an Arduino, you will need the following components:

Here are the steps to connect the DS18B20 temperature sensor to the Arduino:

Connect the Vcc pin of the DS18B20 sensor to the 5 V pin on the Arduino.

Connect the GND pin of the DS18B20 sensor to the GND pin on the Arduino.

Connect the data pin (middle pin) of the DS18B20 sensor to a digital input/output (I/O) pin on the Arduino. In this example, we will use digital pin 2.

Connect a 4.7 k ohm resistor between the data pin and the 5 V pin on the Arduino.

Connect the Arduino to your computer via USB cable.

Open the Arduino IDE and create a new sketch.

In the sketch, include the OneWire and DallasTemperature libraries. These libraries can be installed from the Arduino IDE Library Manager.

Initialize the OneWire and DallasTemperature libraries in the setup() function of the sketch.

In the loop() function of the sketch, read the temperature data from the DS18B20 sensor using the DallasTemperature library functions. The code would look something like this:

In this code, we first define the data pin (digital pin 2) as ONE_WIRE_BUS. Then we initialize the OneWire and DallasTemperature libraries in the setup() function. In the loop() function, we first use the requestTemperatures() function to request the temperature data from the DS18B20 sensor. Then we use the getTempCByIndex(0) function to get the temperature in degrees Celsius. Finally, we print the temperature to the serial monitor and add a delay of 1 s before the next reading.

- 10.

Upload the sketch to the Arduino board, and open the serial monitor to see the temperature readings.”

According to the given response, we validated the steps by the datasheet. The component list was valid, as well the connections of the pins and components. Even highlighting the 1-Wire communication was correct. The official datasheet backs up our findings about the response [

31]. The suggested code is also working, but minimal knowledge of the IDE (Integrated Development Environment) is required to assess the steps given by the bot. We also did the query with the DHT11

Supplementary Materials, and we received again, convincing points. The datasheet was suggesting that the pin alignment was correct [

32]. However, there was a DHT library recommendation, which all authors agreed upon, that was not straightforward to understand and include with the work. Overall, it was found that more preliminary knowledge is required to use the second query, and it was found that the depth of the solution might vary from use case to use case.

To the question about the origins of the suggestions, ChatGPT responded with a sound answer:

ChatGPT: “I wrote the code example based on my knowledge and experience with using the OneWire and DallasTemperature libraries to read temperature data from a DS18B20 sensor. However, the code structure and some of the function calls may be similar to code examples found in the official Arduino documentation, online forums or tutorials.”

The question regarding the use of an MQ-4 gas sensor was also asked from the bot. This time the results were considerably less reliable. ChatGPT cited the datasheet of the MQ-4 sensor for a formula [

33], where the datasheet did not contain such information. So, human validation was again required at this point to validate the data provided by the bot. From this aspect, the formula was not included in the official support materials, so we can claim this part unreliable.

In the codes, commenting was also found for better understanding; however, the comments were not consequential in their amount and detail. It is a big advantage however that the tool was aware of commenting.

Altogether, ChatGPT can give partially plausible solutions for simple hardware and software tasks, like interfacing a controller and a sensor, but it also gave false findings, which elevates the need of human control over the results.

3.4. Literature Survey on the Topic

About the literature survey, the following question was given to ChatGPT: “Could you do a literature review on smart home control with Arduino for a research paper?” ChatGPT responded with a general introduction on the topic of Arduino in relation with smart home control and gave three literature references as examples. For example:

ChatGPT: “One study by Varghese et al. (2017) presented an Arduino-based smart home system that used a variety of sensors to monitor the temperature, humidity, gas levels and motion in a house. The system also included automatic control of lights and fans based on occupancy and environmental conditions. The authors reported that the system was able to improve energy efficiency and reduce utility costs.”

When we asked about the citations, ChatGPT provided a plausible response at first glance. The following citation was presented for the article above.

ChatGPT: “Varghese, J., Jayachandran, S., & Jayachandran, S. (2017). An Arduino based smart home system. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, 114(10), 505–514.”

Looking for the given citation in widely used search-engines (Google Scholar, Academia.edu) and in the article list of the given journal, it was found that this paper did not ever exist. The names of the authors were found in similar research topics, but it was an initial red flag that the second and third authors were the same (Jayachandran, S.). Also, the title is a fabricated one, as well as the rest of the bibliographic information. In the next step, ChatGPT was asked to give references to scientific literature (recommend articles) regarding Arduino as a sensor controller (also including the DOI numbers of the papers). The response was a list of five references, with similarly false information. During the investigations, an interesting aspect was revealed about the following suggested article:

ChatGPT: “J. R. de Sousa and M. F. de Sousa, “Data acquisition and control system based on Arduino platform for low-cost greenhouse monitoring,” Measurement, vol. 168, p. 108273, Jan. 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108273”

It turns out, there is no such article available on the web. But the DOI seemed to be in connection with the given journal, which would also fool the unsuspecting eye, believing that the reference is correct. The DOI is an existing one, but it does not refer to the given article. The paper of Ziolowsky et al. has nothing to do with the discussed applied sensors topic [

34].

For the question on the actual help for fitting sensors to Arduino, the bot provided five references with short descriptions, and four out of them were actually accessible. One of these examples was not a live link, but the browser forwarded the request to a proper one. The given link “

https://www.arduino.cc/en/Tutorial/HomePage (accessed on 29 March 2023)” seemed to forward us to the actual (current) document repository of Arduino [

35]. This case needed deeper assessment. The link was fed to the reliable Archive.Org “Wayback Machine”, and it turned out that the archived (March 2023) link is redirected to the actual repository as shown above with the following HTTP response [

36]:

16:41:50 March 26, 2023

Got an HTTP 302 response at crawl time | Redirecting to…

According to Archive.org [

36], it seemed that 04:07:56, 4 January 2022 was the last timestamp, when the originally suggested link was accessible. This is in line with the communicated capability of ChatGPT 3.5, that is, relying on a 2021 learning database—the bot could not know that the tutorials were removed to an alternative website.

3.5. An Outlook and Comparison with Bing

While the basic assumption to compare Bing to the closed database-trained ChatGPT 3.5 is not a balanced act, we asked the questions on controllers, argument on them, sensor types, specific information on getting started and specific literature. All details are available in

Supplementary Materials.

We found that Bing gave us five valid controllers (when asked about 4–6 different types, pointing to a middle solution in quantity). The arguments and information were valid, but the descriptions were a bit shorter. Out of five examples, four were the same with the recommendations of GPT. Also, Arduino was the primary choice here as well.

As for sensor types, Bing gave eight different sensors, where most of them were healthcare based ones. So the focus was much more precise in the case of ChatGPT. For a more specific query on temperature sensors, five different types were listed. DS18B20 was highlighted again as a widely used one. Bing could recommend altogether 17 valid links for tutorials and videos. This aspect is clearly realized by the connection to the web.

While we asked for at least five literature references, we were given five articles. Four articles were available of the five ones, but three articles were written by other authors as it was stated by the bot. Also, all of the DOIs were imprecise. Most links were cited from ResearchGate, which might come from the bias to search in open access materials and libraries. It can be stated that even this tool has problems, so literature survey with the tool is not acceptable from academic precision aspects.

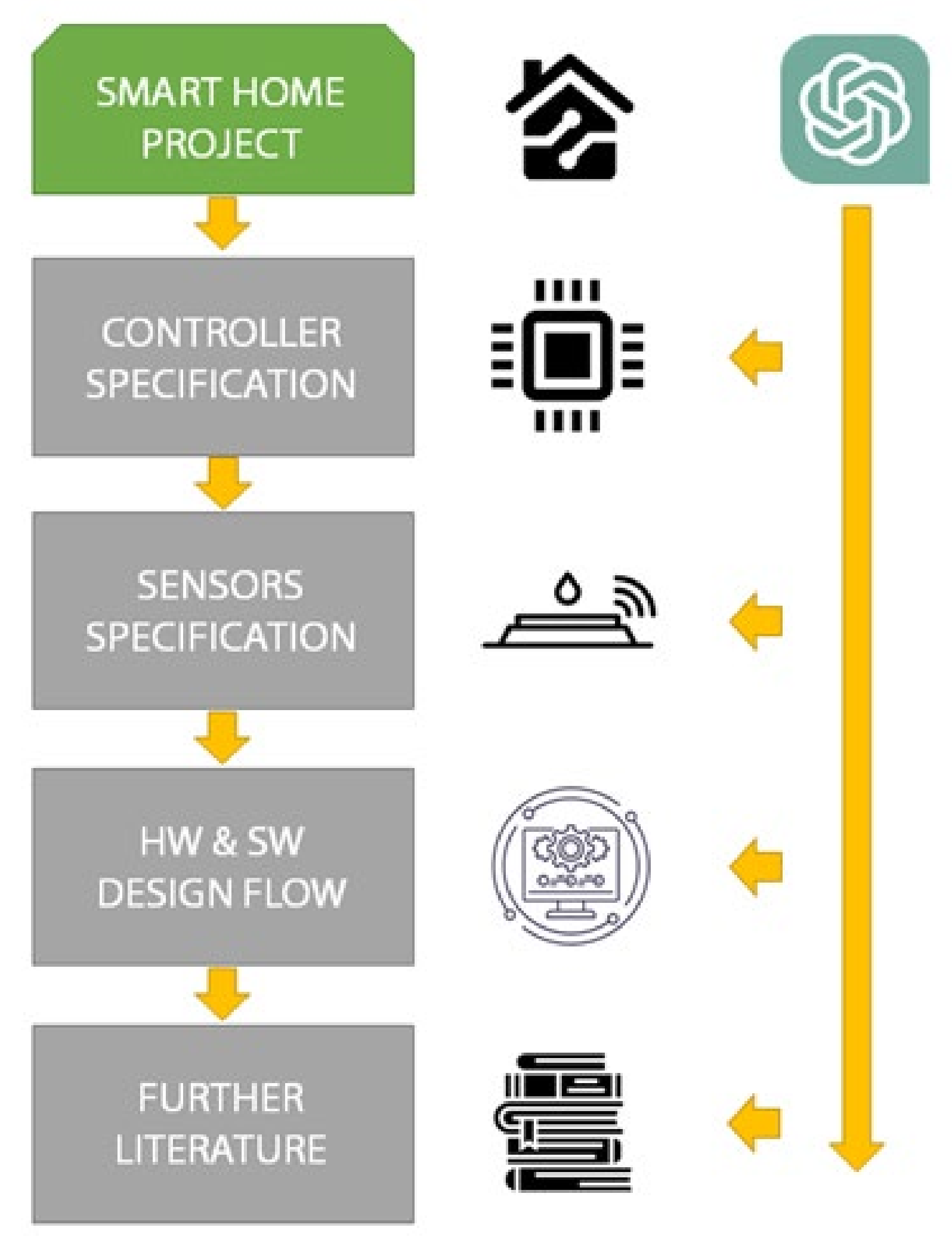

4. Discussion

The summary of our findings is presented in

Figure 2 and in the performance metrics

Table 1, based on the work of Lo [

37]. We found that ChatGPT was able to narrow down an initial assumption in developing a smart home project with a proper choice of controllers and sensors. The bot gave superficial but altogether usable recommendations for a controller, choosing from a wide range of items, limited by the its training. It also described a wide range of sensors for the project, with relevant descriptions accessible to even a beginner practitioner in the field.

As for the sensors and specifications, the bot was able to sort out different sensor types for the task, which were fitting to the request, and which are still on the market. The sorting of the sensors was correct from the aspect of the price, but the listings (or groupings) were inconsistent from the aspect of sensor type (by measurement principle) and actual sensor component type. We also found that most of the sensor specifics were correct, but around 10% of the given parameters were imprecise (albeit in range, close to the actual values). The bot was able to follow the discussion via initial assumptions fixed in the queries (such as following up with the Arduino platform). The bot was also giving popular examples and was not focusing on very specific components but widely available ones. If the training dataset is new enough, mistakes in given data could be less, and exact parameters could be more precise; however, various versions of datasheets floating around (e.g., in the case of cheap Far East sensors) might also leave space for confusion.

The workflow of interfacing a sensor module to a controller was covered by the ChatGPT in a partially proper manner. It was able to give appropriate design solutions for physically interfacing the sensor module and also generated a code that provided correct syntax and references to the application of the given sensor module. The request was repeated with another sensor component, where the answers were similarly convincing, but contained minor errors. It must be noted that the task was relatively simple. However, at this level, the bot can help engineers in the learning phase or give an immediate response for a task, which would eventually require a significant amount of working hours.

The capability of the bot for a literature survey is found to be unreliable. It recommends seemingly correct and relevant citations for given technical themes. But all of them are fake, fabricated by relevant keywords, existing authors, journal names and DOIs, which are real but incorrect for the actual examples. It is suggested that in the nature of this LLM, the bot is assembling keyword-based information and cannot handle large, coherent data, like a literature citation. Or simply, the literature is not available to the bot due to commercial nature. In a very recent study, there is a suggestion, that the ChatGPT is more like a creative tool in case of literature analysis than exact documentation assistant [

38]. However, it further raises questions about how the information is handled in other scientific fields; as the aforementioned review material mentions [

39], most papers seem optimistic from the data organizing side capabilities (e.g., in hypothesis validation or the identification of gaps and inconsistencies in current knowledge). The fabricated literature responses had an added value though: It contained coherent listings of thematically correct key-words, which could further aid the literature survey of a human learner or a beginner in the field. It is important to note that for more technical or commercial related information (such as datasheets and tutorials), ChatGPT could provide four accessible links out of five. One link was an older one, but it was automatically redirected to a working page by the host.

It has to be also noted that the flow of the discussion cannot be reinstated or repeated in the same manner, so further information and branching discussions are given to the user distinctively from time to time. Our experiment presented a use case that is not classically reproducible in the traditional manner. This also makes it more difficult to assess the application of the tool from both technical and societal aspects.

Overall, our results are clarifying the technical depth and precision of the literature survey shown in [

5,

6,

11], showing that exact literature survey, or “searching” can be unreliable. The partially acceptable results with minor failures were similar to be found in [

4]. As we found, the accessibility and applicability of the tool points to a curious recommendation, which is similar to [

18,

19,

20]. The performance analysis was similar to other ChatGPT use cases [

37].

5. Conclusions

In this article, we investigated the applicability of the novel LLM-based ChatGPT for electrical engineering development of a smart home project. ChatGPT followed our queries with a consistent manner, focusing on the controller and narrowing down the question to different sensor types, their interfacing, some exemplary software and related literature.

It was found that the sensor recommendations were valid, but part of the given specification, prices, hardware-software integration and the resulting code were slightly imprecise, which needed human validation. Furthermore, the listings were inconsistent from the sensor type and commercial module type aspects.

It was found that, by requesting actual scientific literature (articles, journal papers), the results were fabricated, fake and unreliable. However, with limited usability, technical documentation was referenced correctly by ChatGPT, and the key words were found to be accurate.

Interestingly, it was found that Bing (connected to the web) made similar performance as the older ChatGPT 3.5 version, where controller choice was acceptable, sensor technical details were containing minor problems, and literature survey was unacceptable.

For the future, similar tasks should be investigated with the continuously evolving versions and the competitors, such as the recently launched Bing or the Bard platform. The work could be continued with the inclusion of PCB (printed circuit board) design and related simulations. Our work does not tackle the ethical side and fair, responsible use, which is a societal aspect. Concerns are high regarding the application of such tools; even leading professionals are asking for a “pause time” from AI developers to catch up with regulations. Also, it is suggested to focus on information technology and engineering R&D aspects during the development of further releases. As the tool is coming from the same broadly interpreted profession, as our field, it would be important for the tool to meet requirements in data precision (especially with literature and technical information), so that it does not include errors to the developers working with it.

The takeaway message is that, with proper regulations and future improvements, chatbots can be an effective device in electronics development projects, as a supplementary tool in the available, traditional toolset.