Synthesis, Characterization and Spectral Properties of Substituted Tetraphenylporphyrin Iron Chloride Complexes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

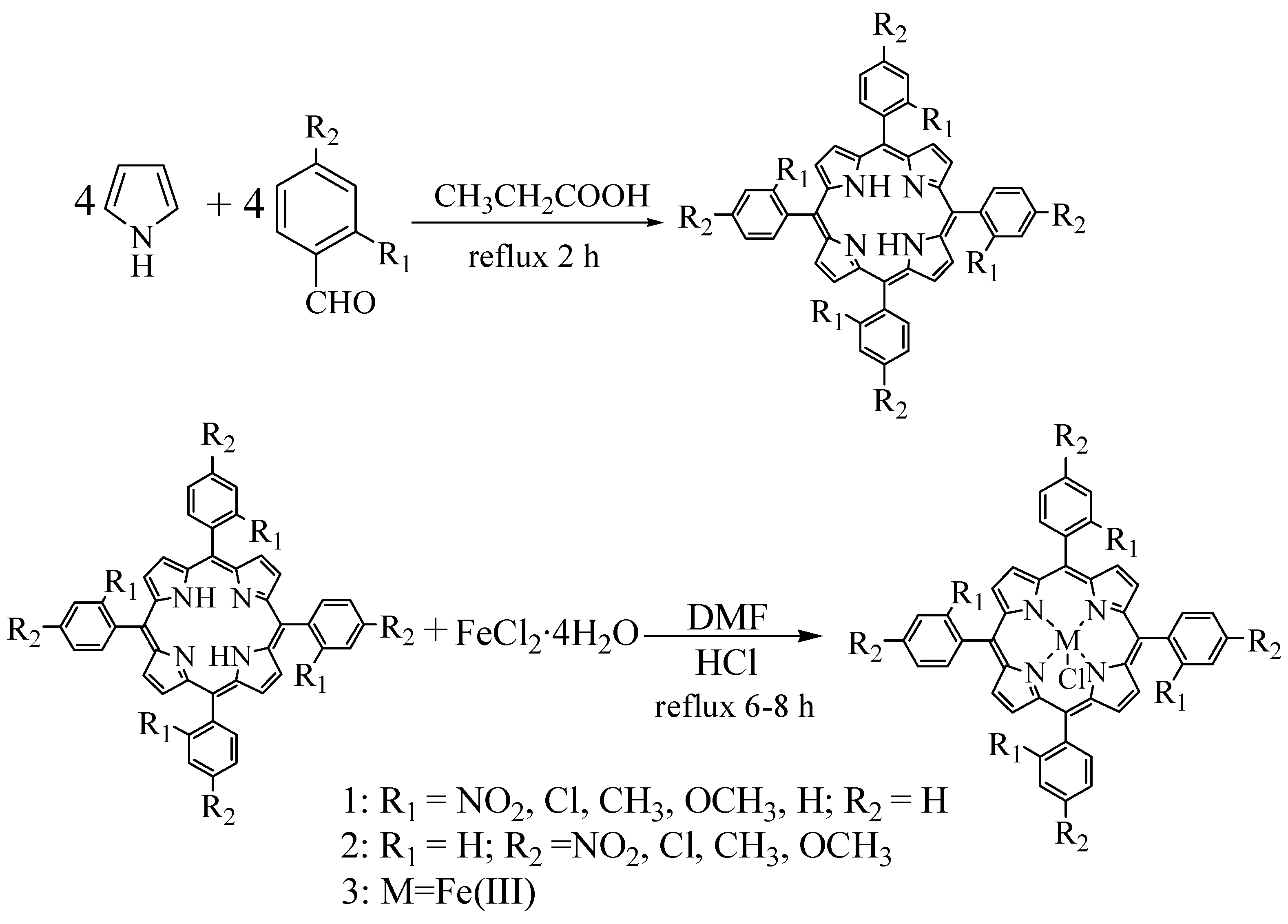

2.1. Synthesis with One-pot and Two-step Methods

2.2. Spectral Analysis of RTPPFe(III)Cl

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials and Instruments

3.2. Synthesis of RTPPFe(III)Cl

3.2.1. Synthesis–Adler Two-step Method

3.2.2. Synthesis–One-pot Mixed Solvent Method

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- Haber, J.; Matachowski, L.; Pamin, K.; Poltowicz, J. The effect of peripheral substituents in metalloporphyrins on their catalytic activity in Lyons system. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2003, 198, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharieva, O.; Trautwein, A.X.; Veeger, C. Porphyrin-Fe(III)-hydroperoxide and porphyrin-Fe(III)-peroxide anion as catalytic intermediates in cytochrome P450-catalyzed hydroxylation reactions: a molecular orbital study. Biophys. Chem. 2000, 88, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourre, L.; Simonneaux, G.; Ferrand, Y.; Thibaut, S.; Lajat, Y.; Patrice, T. Synthesis, and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of a diphenylchlorin sensitizer for photodynamic therapy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2003, 69, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesaga, M.; Orska, J.; Fiertek, D.; Izdebski, J.; Trojanowicz, M. Immobilized metal-ion affinity chromatography of peptides on metalloporphyrin stationary phases. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 1999, 364, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drain, C.M.; Russell, K.C.; Lehn, J.M. Self-assembly of a multi-porphyrin supramolecular macrocycle by hydrogen bond molecular recognition. Chem. Commun. 1996, 3, 337–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S.; Nagano, S.; Ishimori, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Morishima, I.; Egawa, T.; Kitagawa, T.; Makino, R. Roles of proximal ligand in heme proteins: replacement of proximal histidine of human myoglobin with cysteine and tyrosine by site-directed mutagenesis as models for P-450, chloroperoxidase, and catalase. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebert, D.W.; Dalton, T.P. The role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in endogenous signalling pathways and environmental carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Ji, H.B.; Chen, Y.X.; Han, Y.; Song, X.F.; She, Y.B.; Zhong, R.G. Oxidation of cyclohexane to adipic acid using Fe-porphyrin as a biomimetic catalyst. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2004, 8, 418–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Z.; She, Y.B.; Zhong, R.G.; Ji, H.B.; Zhang, Y.H.; Song, X.F. A green process for oxidation of p-nitrotoluene catalyzed by metalloporphyrins under mild conditions. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2006, 10, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, R.; Tehrani, A.A.; Fard, M.A.; Sadegh, B.M.M.; Khavasi, H.R. First catalytic application of metal complexes of porpholactone and dihydroxychlorin in the sulfoxidation reaction. Catal. Commun. 2009, 11, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, B. Metalloporphyrins as versatile catalysts for oxidation reactions and oxidative DNA cleavage. Chem. Rev. 1992, 92, 1411–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothemund, P. A new porphyrin synthesis. The synthesis of porphin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1936, 58, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.D.; Longo, F.R.; Finarelli, J.D.; Assour, J.; Korsakoff, L. A simplified synthesis for meso-tetraphenylporphine. J. Org. Chem. 1967, 32, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, J.S.; Schreiman, I.C.; Hsu, H.C.; Kearney, P.C.; Marguerettaz, A.M. Rothemund and Adler-Longo reactions revisited: synthesis of tetraphenylporphyrins under equilibrium conditions. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Maji, S.; Abhilash, G.J.; Pandey, S.; Sarkar, S. One-pot general synthesis of metalloporphyrins. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 7287–7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharghi, H.; Nejad, A.H. Phosphorus pentachloride (PCl5) mediated synthesis of tetraarylporphyrins. Helv. Chim. Acta 2003, 86, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Senge, M.O.; Smith, K.M. Simple methodology for syntheses of porphyrins possessing multiple peripheral substituents with an element of symmetry. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.R.; Latter, M.J.; Warrener, R.N. Porphyrin-containing molecular capsules: metal mediated dimerization of a bis-porphyrin cavity. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 2165–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha Gonsalves, A.M.d’A.; Varejao, J.M.T.B.; Pereira, M.M. Some new aspects related to the synthesis of meso-substituted porphyrins. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1991, 28, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.C.; Rocha Gonsalves, A.M.d’A. Controlled porphyrinogen oxidation for the selective synthesis of meso-tetraarylchlorins. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 4192–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, G.R., III; Chick, J.F.B.; Callinan, J.B.; Reid, C.G.; Auguscinski, W.P. A survey of acid catalysis and oxidation conditions in the two-step, one-flask synthesis of meso-substituted corroles via dipyrromethanedicarbinols and pyrrole. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 4159–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, N.; Kawamura, H.; Bougauchi, M.; Maruyama, K. Porphyrin synthesis from nitrocompounds. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 7483–7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothemund, P. Formation of porphyrins from pyrroles and aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1935, 57, 2010–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothemund, P.; Menotti, A.R. Porphyrin studies. IV. The synthesis of α,β,γ,δ-tetraphenylporphine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941, 63, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.D.; Longo, F.R.; Shergalis, W. Mechanistic investigation of porphyrin syntheses. I. Preliminary studies on ms-tetraphenylporphin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3145–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, J.S.; MacCrum, K.A.; Tyhonas, J.S.; Chuang, Y.Y. Investigation of a synthesis of meso-porphyrins employing high concentration conditions and an electron transport chain for aerobic oxidation. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.R.; Yang, K.X.; Tyhonas, J.S.; Maccrum, K.A.; Lindsey, J.S. Beneficial effects of salts on an acid-catalyzed condensation leading to porphyrin formation. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 12339–12360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.D.; Longo, F.R.; Kampas, F.; Kim, J. On the preparation of metalloporphyrins. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1970, 32, 2443–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, R.A.W.; Nunes, M.L.P.G.; Pereira, M.M.; Rocha Gonsalves, A.M.d’A.; Serra, A.C. Improved syntheses of 5,10,15,20-tetrakisaryl- and tetrakisalkylporphyrins. Heterocycles 1996, 43, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, K.; Spiro, T.G. Core expansion, ruffling, and doming effects on metalloporphyrin vibrational frequencies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 3793–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors. |

| No. | Compounds | Optimum ratios of solvents (one-pot method) | Total yields (one-pot method) (%) | Total yields (two-step method) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | o-NO2TPPFeCl | 70:10:20 | 28.7 | 13.1 |

| 2 | o-ClTPPFeCl | 40:20:20 | 31.8 | 9.7 |

| 3 | o-CH3TPPFeCl | 40:20:20 | 33.6 | 16.7 |

| 4 | o-OCH3TPPFeCl | 70:10:20 | 32.5 | 5.7 |

| 5 | TPPFeCl | 70:10:20 | 38.3 | 18.4 |

| 6 | p-NO2TPPFeCl | 40:20:20 | 30.1 | 5.6 |

| 7 | p-ClTPPFeCl | 40:20:20 | 40.4 | 16.7 |

| 8 | p-CH3TPPFeCl | 70:10:20 | 32.7 | 15.4 |

| 9 | p-OCH3TPPFeCl | 40:20:20 | 35.9 | 13.0 |

| No. | Compounds | λmax (nm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soret bands | Q bands | |||||

| 1 | o-NO2TPP | 421 | 516 | 551 | 593 | 650 |

| 2 | o-ClTPP | 412 | 511 | 542 | 587 | 642 |

| 3 | o-CH3TPP | 416 | 512 | 544 | 589 | 645 |

| 4 | o-OCH3TPP | 417 | 512 | 545 | 589 | 643 |

| 5 | TPP | 417 | 514 | 538 | 585 | 620 |

| 6 | p-NO2TPP | 424 | 516 | 551 | 594 | 604 |

| 7 | p-ClTPP | 418 | 514 | 549 | 589 | 645 |

| 8 | p-CH3TPP | 419 | 516 | 551 | 592 | 647 |

| 9 | p-OCH3TPP | 421 | 518 | 555 | 593 | 650 |

| 10 | o-NO2TPPFeCl | 422 | 510 | 579 | ||

| 11 | o-ClTPPFeCl | 418 | 505 | 576 | ||

| 12 | o-CH3TPPFeCl | 416 | 511 | 585 | ||

| 13 | o-OCH3TPPFeCl | 418 | 513 | |||

| 14 | TPPFeCl | 418 | 507 | 572 | ||

| 15 | p-NO2TPPFeCl | 421 | 514 | 584 | ||

| 16 | p-ClTPPFeCl | 417 | 509 | 573 | ||

| 17 | p-CH3TPPFeCl | 418 | 452 | 511 | ||

| 18 | p-OCH3TPPFeCl | 420 | 509 | 572 | ||

| No. | Compounds | IR (cm−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| νN-H (δN-H) | ν=C-H | νC=C | νC=N | γ=C-H | νFe-N | νFe-Cl | ||

| 1 | o-NO2TPP | 3321 (968) | 3060 | 1606 | 1349 | 722 | — | — |

| 2 | o-ClTPP | 3325 (967) | 3056 | 1626 | 1346 | 750 | — | — |

| 3 | o-CH3TPP | 3315 (965) | 3016 | 1599 | 1348 | 739 | — | — |

| 4 | o-OCH3TPP | 3322 (966) | 3070 | 1580 | 1349 | 753 | — | — |

| 5 | TPP | 3309 (966) | 3051 | 1594 | 1352 | 732 | — | — |

| 6 | p-NO2TPP | 3322 (967) | 3055 | 1595 | 1347 | 800 | — | — |

| 7 | p-ClTPP | 3315 (965) | 3024 | 1627 | 1349 | 796 | — | — |

| 8 | p-CH3TPP | 3317 (967) | 3024 | 1561 | 1349 | 798 | — | — |

| 9 | p-OCH3TPP | 3320 (967) | 2925 | 1596 | 1346 | 805 | — | — |

| 10 | o-NO2TPPFeCl | — | 2925 | 1607 | 1345 | 740 | 999 | 367 |

| 11 | o-ClTPPFeCl | — | 2923 | 1673 | 1334 | 754 | 999 | 370 |

| 12 | o-CH3TPPFeCl | — | 3014 | 1598 | 1332 | 753 | 998 | 361 |

| 13 | o-OCH3TPPFeCl | — | 2934 | 1596 | 1334 | 756 | 998 | 360 |

| 14 | TPPFeCl | — | 2923 | 1597 | 1340 | 750 | 991 | 379 |

| 15 | p-NO2TPPFeCl | — | 2925 | 1595 | 1346 | 802 | 999 | 368 |

| 16 | p-ClTPPFeCl | — | 3133 | 1682 | 1338 | 805 | 999 | 359 |

| 17 | p-CH3TPPFeCl | — | 3022 | 1494 | 1338 | 799 | 999 | 360 |

| 18 | p-OCH3TPPFeCl | — | 2923 | 1605 | 1334 | 810 | 998 | 359 |

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Z.-C.; She, Y.-B.; Zhou, Y.; Song, X.-F.; Li, K. Synthesis, Characterization and Spectral Properties of Substituted Tetraphenylporphyrin Iron Chloride Complexes. Molecules 2011, 16, 2960-2970. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16042960

Sun Z-C, She Y-B, Zhou Y, Song X-F, Li K. Synthesis, Characterization and Spectral Properties of Substituted Tetraphenylporphyrin Iron Chloride Complexes. Molecules. 2011; 16(4):2960-2970. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16042960

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Zhi-Cheng, Yuan-Bin She, Yang Zhou, Xu-Feng Song, and Kai Li. 2011. "Synthesis, Characterization and Spectral Properties of Substituted Tetraphenylporphyrin Iron Chloride Complexes" Molecules 16, no. 4: 2960-2970. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16042960