Pro-Apoptotic Effect of Rice Bran Inositol Hexaphosphate (IP6) on HT-29 Colorectal Cancer Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

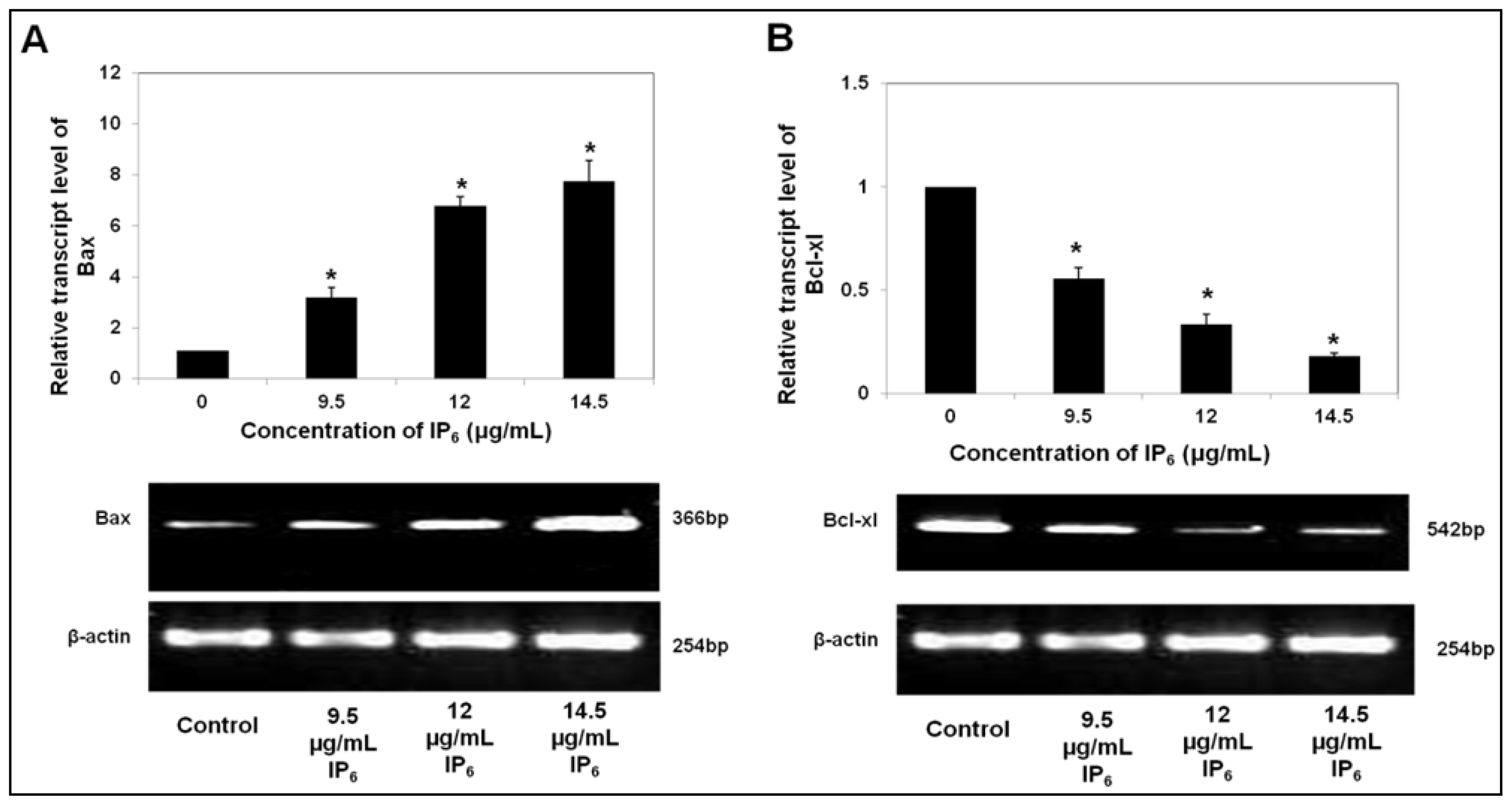

2.1. IP6 Induces Apoptosis and Regulates the mRNA Level of Pro- and Anti-Apoptotic Bax and Bcl-xl Expression

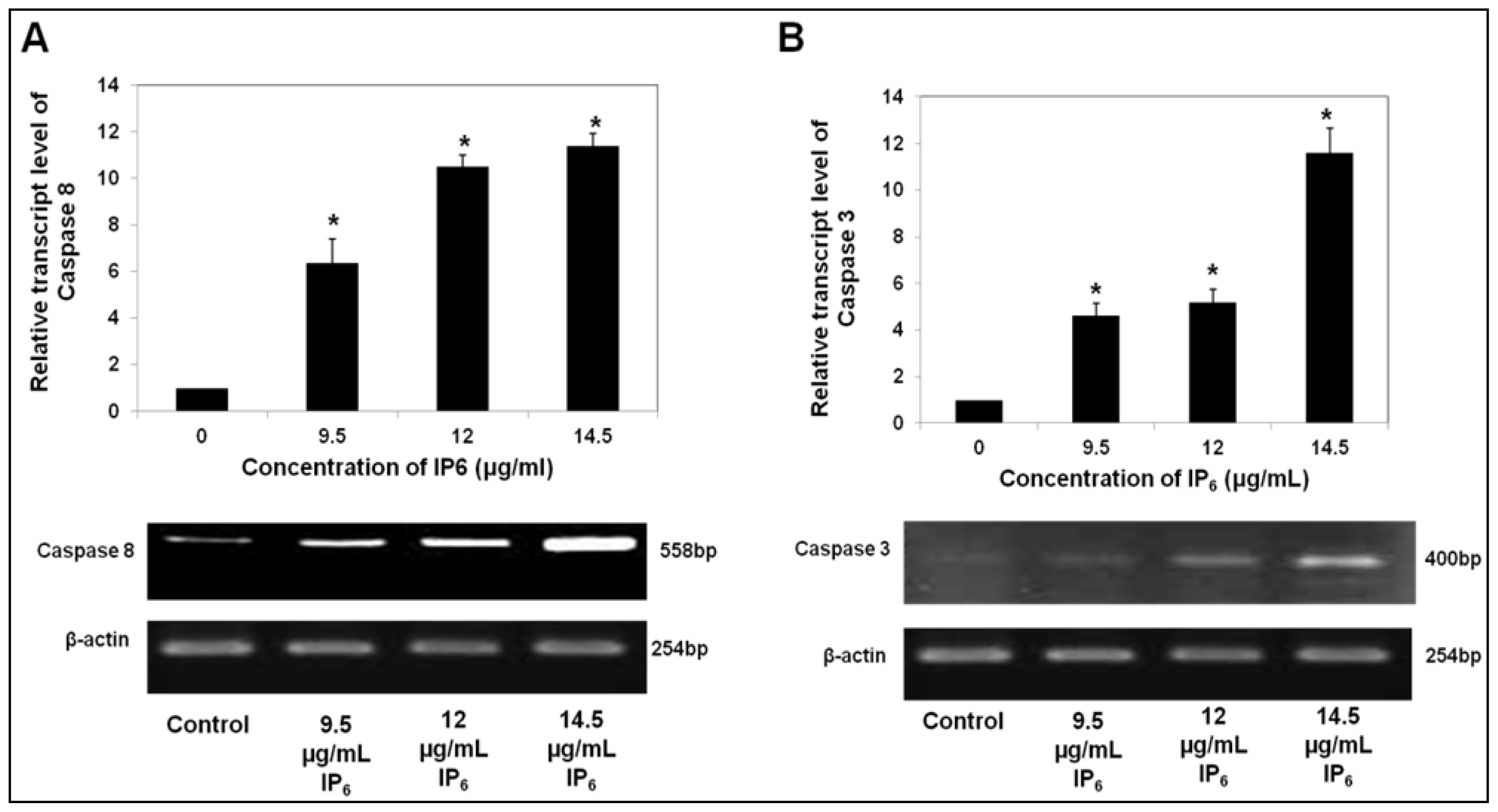

2.2. IP6 Upregulates Caspase Gene Expression

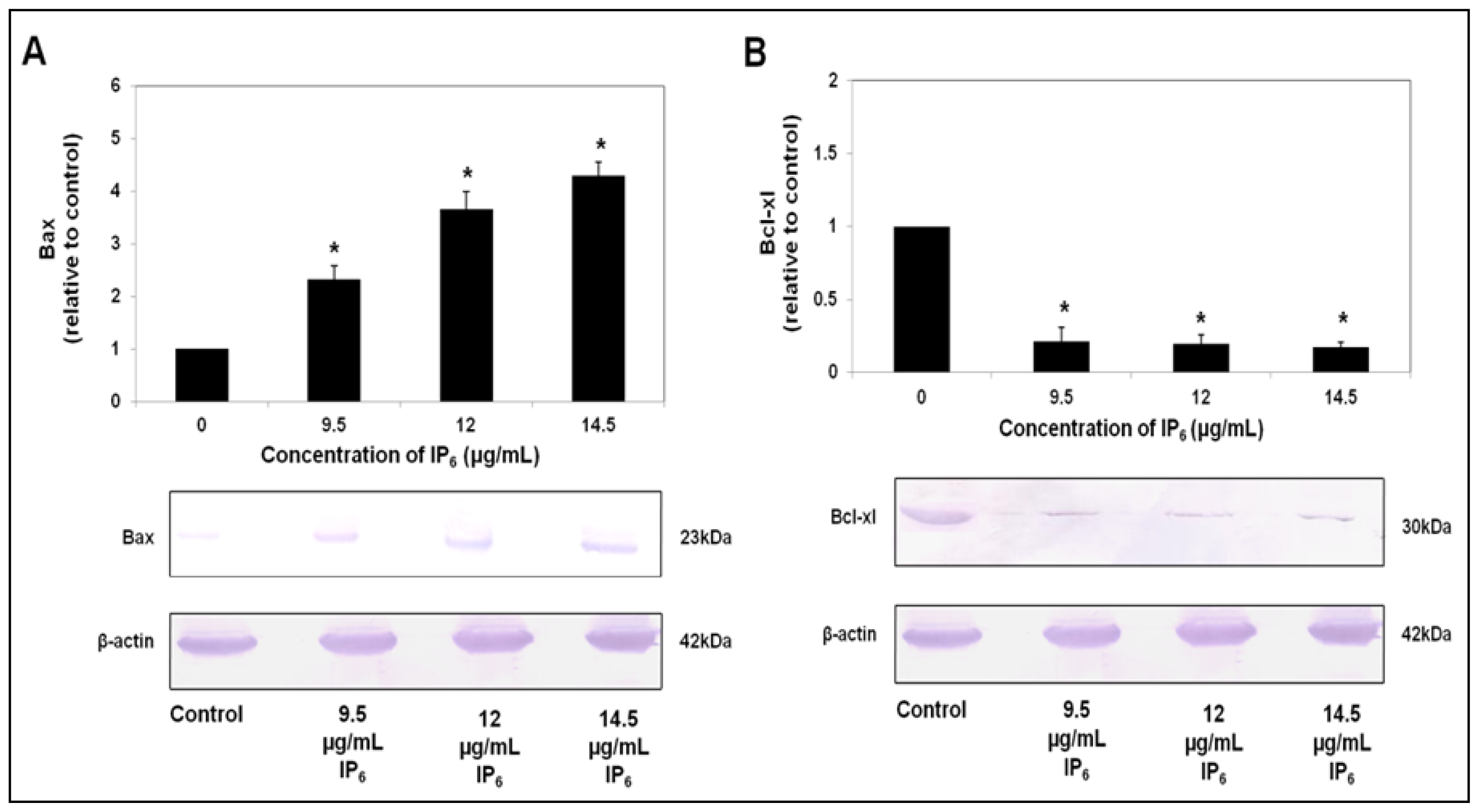

2.3. IP6 Modulates Apoptosis Related Protein Expression, Bax and Bcl-xl

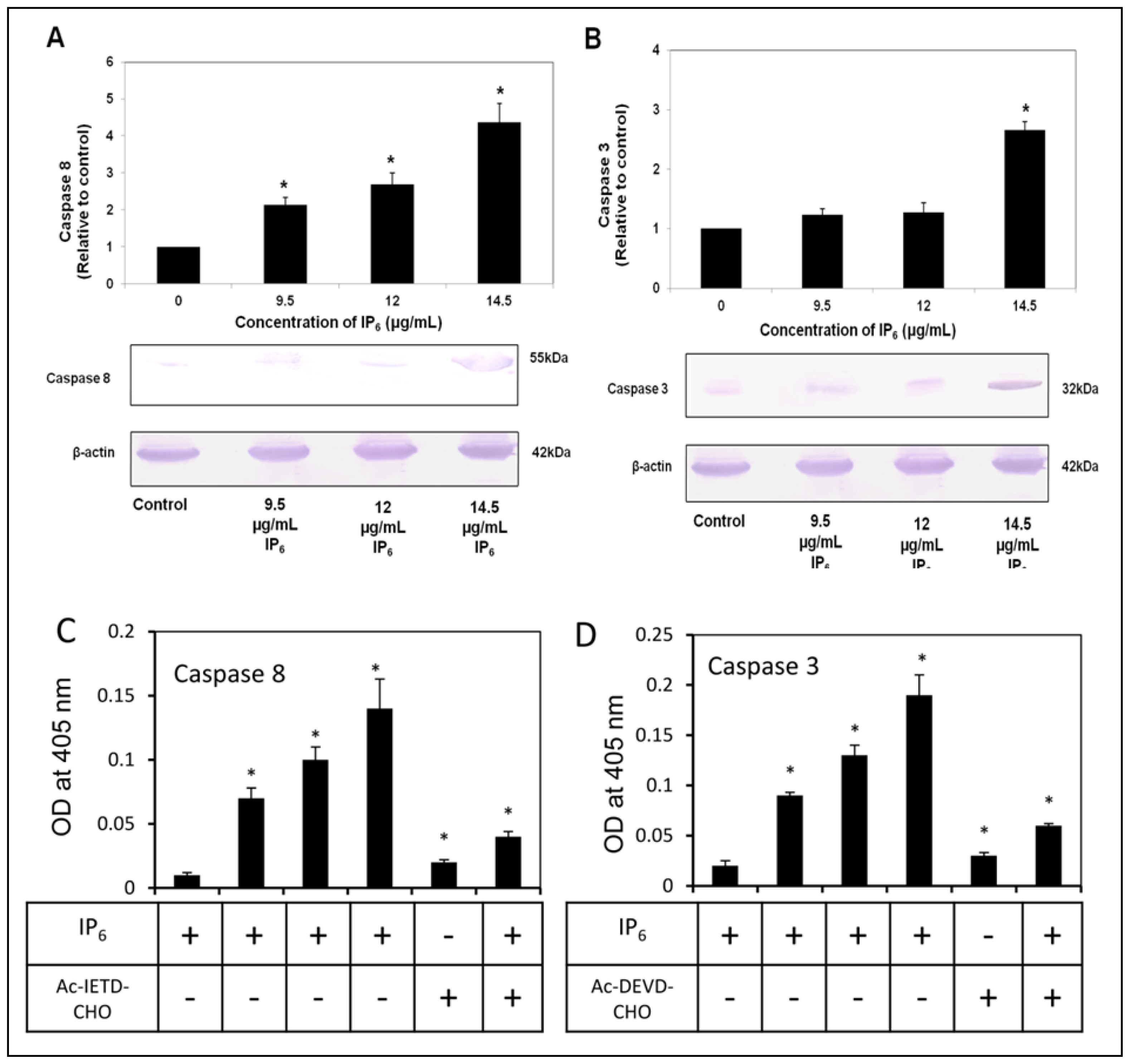

2.4. IP6 Activates Caspase-8 and -3

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Sections

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Sample Preparation

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Quantification of Apoptosis Related Genes by Real-Time PCR

4.5. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

4.6. Western Blot Analysis

4.7. Measurement of Caspase-3 and 8 Activities

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Shin, H.R.; Bray, F.; Forman, D.; Mathers, C.; Parkin, D.M. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: Globocan 2008. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 2893–2917. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R.; Naishadham, D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA: Cancer J. Clin 2012, 62, 10–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, W.C.; Weinberg, R.A. Mechanisms of disease: Rules for making human tumor cells. N. Engl. J. Med 2002, 347, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar]

- Rieger, P.T. The biology of cancer genetics. Semin. Oncol. Nurs 2004, 20, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, S.C.; Giovannucci, E.; Bergkvist, L.; Wolk, A. Whole grain consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: A population-based cohort of 60,000 women. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 92, 1803–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, L.R.; Harris, P.J. Studies on the role of specific dietary fibres in protection against colorectal cancer. Mutat. Res 1996, 350, 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kasim, A.B.; Edwards, H.M., Jr. The analysis for inositol phosphate forms in feed ingredients. J. Sci. Food Agric 1998, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jariwalla, R.J. Rice bran products: Phytonutrients with potential applications in preventive and clinical medicine. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res 2001, 27, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.M.; Cory, S. Bcl-2-regulated apoptosis: Mechanism and therapeutic potential. Curr. Opin. Immunol 2007, 19, 488–496. [Google Scholar]

- Martinou, J.-C.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondria in apoptosis: Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Youle, R.J.; Strasser, A. The BCL-2 protein family: Opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Dev. Mol. Cell Biol 2008, 9, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk, J.E.; Green, D.R. How do Bcl-2 proteins induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization? Trends Cell Biol 2011, 18, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Newmeyer, D.D.; Ferguson-Miller, S. Mitochondria: Releasing power for life and unleash in the machineries of death. Cell 2003, 112, 481–490. [Google Scholar]

- Gerl, R.; Vaux, D.L. Apoptosis in the development and treatment of cancer. Carcinogenesis 2005, 26, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Yue, P.; Zhou, Z.; Khuri, F.R.; Sun, S.Y. Death receptor regulation and celecoxib-induced apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 2004, 96, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.; Shamsuddin, A.M. Dose-dependent inhibition of intestinal cancer by inositol hexaphosphate in F344 rats. Carcinogenesis 1990, 11, 2219–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Vucenik, I.; Sakamoto, K.; Bansal, M.; Shamsuddin, A.M. Inhibition of mammary carcinogenesis by inositol hexaphosphate (phytic acid). A pilot study. Cancer Lett 1993, 75, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Vucenik, I.; Yang, G.Y.; Shamsuddin, A.M. Inositol hexaphosphate and inositol inhibit DMBA-induced rat mammary cancer. Carcinogenesis 1995, 16, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Norazalina, S.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Hairuszah, I.; Norashareena, M.S. Anticarcinogenic efficacy of phytic acid extracted from rice bran on azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in rats. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol 2010, 62, 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Nurul-Husna, S.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Hairuszah, I.; Abdah, M.A.; Norazalina, S.; Norsharina, I. Rice bran phytic acid (IP6) induces growth inhibition, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis on human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. J. Med. Plants Res 2010, 4, 2283–2289. [Google Scholar]

- Norazalina, S.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Hairuszah, I.; Sabariah, A.R.; Nurul Husna, S.; Norsharina, S. Antiproliferation and apoptosis induction of phytic acid in hepatocellular carcinoma (HEPG2) cell lines. Afr. J. Biotechnol 2011, 10, 16646–16653. [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner, M.O. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 2000, 407, 770–776. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchier-Hayes, L.; Lartigue, L.; Newmeyer, D.D. Mitochondria: Pharmacological manipulation of cell death. J. Clin. Invest 2005, 115, 2640–2647. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, P.; Krauskopf, A.; Basso, E.; Petronilli, V.; Blachly-Dyson, E.; di Lisa, F.; Forte, M.A. The mitochondrial permeability transition from in vitro artifact to disease target. FEBS Lett 2006, 273, 2077–2099. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, P.; von Stockum, S. The permeability transition pore as a Ca(2+) release channel: New answers to an old question. Cell Calcium 2012, 52, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Degterev, A.; Boyce, M.; Yuan, J. A decade of caspases. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8543–8567. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Singh, R.P.; Agarwal, R. Growth inhibitory and apoptotic effects of inositol hexaphosphate in transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate (TRAMP-C1) cells. Int. J. Oncol 2003, 23, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Schroterova, L.; Haskova, P.; Rudolf, E.; Cervinka, M. Effect of phytic acid and inositol on the proliferation and apoptosis of cells derived from colorectal carcinoma. Oncol. Rep 2010, 23, 787–793. [Google Scholar]

- Salvesen, G.S. Caspases: Opening the boxes and interpreting the arrows. Cell Death Differ 2002, 9, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Nijhawan, D.; Wang, X. Mitochondrial activation of apoptosis. Cell 2004, 116, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Katunuma, N.; Matsui, A.; Le, Q.T.; Utsumi, K.; Salvesen, G.; Ohashi, A. Novel procaspase-3 activating cascade mediated by lysoapoptases and its biological significances in apoptosis. Adv. Enzyme Regul 2001, 41, 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Pandurangan, A.K.; Dharmalingam, P.; Ananda Sadagopan, S.K.; Ramar, M.; Munusamy, A.; Ganapasam, S. Luteolin induces growth arrest in colon cancer cells through involvement of Wnt/β-catenin/GSK-3β. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol 2013, 32, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Czerski, L.; Nuñez, G. Apoptosome formation and Caspase activation: Is it different in the heart? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 2004, 37, 643–652. [Google Scholar]

- Shafie, N.H.; Mohd Esa, N.; Ithnin, H.; Md Akim, A.; Saad, N.; Pandurangan, A.K. Preventive Inositol Hexaphosphate (IP6) extracted from rice bran inhibits colorectal cancer through involvement of Wnt/β-catenin and COX-2 pathways. BioMed Res. Int 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, N.; Esa, N.M.; Ithnin, H.; Shafie, N.H. Optimization of optimum condition for phytic acid extraction from rice bran. Afr. J. Plant Sci 2011, 5, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pandurangan, A.K.; Dharmalngam, P.; Anandasadagopan, S.K.; Ganapasam, S. Effect of luteolin on the levels of glycoproteins during azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in mice. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev 2012, 13, 1569–1573. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, K.; Bai, B.R.; Devaraj, S.N. Cardioprotective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidins on isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in rats. Int. J. Cardiol 2007, 115, 326–333. [Google Scholar]

| Pair No | Primer Name | Accession No | Sequence Location | Oligonucleotides (5′–3′) Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bax | L22473 | nt 172–195 | F-AAGCTGAGCGAGTGTCTCAAGCGC |

| nt 516–537 | R-TCCCGCCACAAAGATGGTCACG | |||

| 2 | Bcl-xL | Z23115 | nt 381–402 | F-ATGGCAGCAGTAAAGCAAGCGC |

| nt 903–922 | R-TTCTCCTGGTGGCAATGGCG | |||

| 3 | Caspase-3 | U26943 | nt 340–361 | F-TTTGTTTGTGTGCTTCTGAGCC |

| nt 720–739 | R-ATTCTGTTGCCACCTTTCGG | |||

| 4 | Caspase-8 | X98172 | nt 1064–1087 | F-GGGACAGGAATGGAACACACTTGG |

| nt 1597–1621 | R-TCAGGATGGTGAGAATATCATCGCC | |||

| 5 | β-actin | X00351 | nt 936–955 | F-CTGTCTGGCGGCACCACCAT |

| nt 1170–1189 | R-GCAACTAAGTCATAGTCCGC |

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Shafie, N.H.; Esa, N.M.; Ithnin, H.; Saad, N.; Pandurangan, A.K. Pro-Apoptotic Effect of Rice Bran Inositol Hexaphosphate (IP6) on HT-29 Colorectal Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 23545-23558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141223545

Shafie NH, Esa NM, Ithnin H, Saad N, Pandurangan AK. Pro-Apoptotic Effect of Rice Bran Inositol Hexaphosphate (IP6) on HT-29 Colorectal Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(12):23545-23558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141223545

Chicago/Turabian StyleShafie, Nurul Husna, Norhaizan Mohd Esa, Hairuszah Ithnin, Norazalina Saad, and Ashok Kumar Pandurangan. 2013. "Pro-Apoptotic Effect of Rice Bran Inositol Hexaphosphate (IP6) on HT-29 Colorectal Cancer Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 12: 23545-23558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141223545