An Evaluation of Healthcare Information on the Internet: The Case of Colorectal Cancer Prevention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Brief Background of Colorectal Cancer Screening

2. Method

2.1. Data Source

| Variables | Definition | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |||

| Compliance with colorectal cancer screening | When did you do your most recent colorectal cancer screening? 1 = COL in past 10 years, or sigmoidoscopy in past 5 years (64%), or FOBT in past 2 years; 0 = otherwise (34%) | 0.65 | 0.48 |

| Independent Variables | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking and Access (Quantity Oriented Information) | |||

| The most recent time you looked for information on cancer, where did you look first? 1 = Internet (29%); 0 = others (71%) | 0.29 | 0.45 |

| In the past 12 months, you used the Internet to look for health or medical information, but did not know where to find it. 0 = very strongly disagree (60%); 1 = strongly disagree (8%); 2 = somewhat disagree (12%); 3 = somewhat agree (13%); 4 = strongly agree (6%) | 0.94 | 1.32 |

| The most recent time you looked for cancer information on the Internet, it took a lot of effort to get the information you needed. 0 = very strongly disagree (70%); 1 = strongly disagree (4%); 2 = somewhat disagree (9%); 3 = somewhat agree (13%); 4 = strongly agree (4%) | 0.73 | 1.25 |

| The most recent time you looked for information on cancer by: 1 = magazines, newspaper, radio, or television (18%); 0 = otherwise (82%) | 0.18 | 0.38 |

| The most recent time you looked for information on cancer, where did you look first? 1 = healthcare provider (19%); 0 = otherwise (81%) | 0.18 | 0.39 |

| Credibility and Reliance of the Cancer Information (Quality Oriented Information) | |||

| The most recent time you looked for cancer information on the Internet, you were satisfied with the information you found. 0 = very strongly disagree (69%); 1 = strongly disagree (1%); 2 = somewhat disagree (4%); 3 = somewhat agree (14%); 4 = strongly agree (12%) | 0.93 | 1.52 |

| The most recent time you looked for cancer information on the Internet, you felt frustrated during your search for the information. 0 = very strongly disagree (69%); 1 = strongly disagree (8%); 2 = somewhat disagree (9%); 3 = somewhat agree (8%); 4 = strongly agree (6%) | 0.67 | 1.20 |

| Regarding receiving information about cancer prevention and early detection on the Internet, how confident are you getting advice or information about cancer if you needed? 0 = very strongly disagree (62%); 1 = not confident at all (1%); 2 = slightly confident (3%); 3 = somewhat confident (11%); 4 = very confident (23%) | 1.27 | 1.75 |

| The most recent time you looked for cancer information on the Internet, the information you found was too hard to understand. 0 = very strongly disagree (70%); 1 = strongly disagree (11%); 2 = somewhat disagree (10%); 3 = somewhat agree (6%); 4 = strongly agree (3%) | 0.58 | 1.05 |

| Imagine that you had a strong need to get information about cancer. Where would you go first? 1 = Internet (16%); 0 = others (84%) (books, brochures, pamphlets, family, friend/co-worker, healthcare provider, library, magazines, newspaper, radio, telephone information, cancer organization, television, cancer research/treatment facility, others) | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| Access to the Internet to look for health or medical information for yourself in the past 12 months; and how much would you trust the information about cancer from newspapers? 0 = not at all (53%); 1 = a little (4%); 2 = some (10%); 3 = more (28%); 4 = a lot (5%) | 1.23 | 1.45 |

| Access to the Internet to look for health or medical information for yourself in the past 12 months; and how much would you trust the information about cancer from television? 0 = not at all (52%); 1 = a little (5%); 2 = some (9%); 3 = more (26%); 4 = a lot (8%) | 1.26 | 1.49 |

| Enabling Factors | |||

| Do you have Medicare health insurance? 1 = yes (56%); 0 = no (44%) | 0.56 | 0.49 |

| Not including psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, is there a particular doctor, nurse or other health professional that you see most often? 1 = yes (82%); 0 = no (18%) | 0.82 | 0.38 |

| What is your annual household income from all sources? 1 = ≤$35,000 (58%); 2 = >$35,000 and ≤$50,000 (14%); 3 = >$50,000 and ≤$75,000 (13%); 4 = >$75,000 (15%) | 1.85 | 1.13 |

| Reinforcing Factors | |||

| An individual’s trust in healthcare provider from the following six items. 6 = minimum; 24 = maximum | 21.25 | 3.23 |

| During the past 12 months, how often did doctors or other health providers listen to you carefully? 1 = never (2%); 2 = sometimes (11%); 3 = usually (22%); 4 = always (65%) | 3.53 | 0.74 |

| How often did they explain things in a way you could understand? 1 = never (2%); 2 = sometimes (10%); 3 = usually (23%); 4 = always (65%) | 3.53 | 0.73 |

| How often did they show respect for what you had to say? 1 = never (1%); 2 = sometimes (7%); 3 = usually (16%); 4 = always (76%) | 3.68 | 0.64 |

| How often did they spend enough time with you? 1 = never (4%); 2 = sometimes (11%); 3 = usually (24%); 4 = always (61%) | 3.45 | 0.81 |

| How often did they involve you in decisions about your health care? 1 = never (4%); 2 = sometimes (11%); 3 = usually (22%); 4 = always (63%) | 3.48 | 0.81 |

| How much would you trust the information about cancer from a doctor or other health professional? 1 = never (3%); 2 = sometimes (6%); 3 = usually (31%); 4 = always (60%) | 3.52 | 0.70 |

| Predisposing Factors | |||

| Knowledge about CRC and CRC screening from the following six items. 0 = minimum point = 1%; 1 = 3%; 2 = 23%; 3 = 32%; 4 = 25%; 5 = 15%; 6 = maximum points = 1% | 3.27 | 1.17 |

| At what age are people supposed to start doing home stool blood tests? 1 = correct, The answer is “age = 50, or when a health provider says”. (33%); 0 = incorrect (67%) | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| In general, once people start doing home blood stool tests, about how often should they do them? 1 = correct, The answer is “every 1 ≤ 2years”. (53%); 0 = incorrect (47%) | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| At what age are people supposed to start having sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy exams? 1 = correct, The answer is “age = 50, or when a health provider says”. (39%); 0 = incorrect (61%) | 0.39 | 0.49 |

| In general, once people start having sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy exams, about how often should they have them? 1 = correct, The answer is “every 5 ≤ 10 years”. (12%); 0 = incorrect (88%) | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Getting checked regularly for colon cancer increases the chances of finding cancer when it is easier to treat. 1 = correct (89%); 0 = incorrect (11%) | 0.89 | 0.32 |

| Do you think having a family history of cancer may affect a person’s chances of getting cancer? 1 = correct (92%); 0 = incorrect (8%) | 0.92 | 0.26 |

| The sum of absolute risk, relative risk, and cancer worry of the following three variables. 3 = minimum; 9 = maximum | 4.41 | 1.45 |

| How likely do you think it is that you will develop colon cancer in the future? 1 = low (62%); 2 = moderate (30%); 3 = high (8%) | 1.46 | 0.64 |

| Compared to the average {man/woman} your age, would you say that you are {_} likely to get colon cancer? 1 = less likely (51%); 2 = about as likely (35%); 3 = more likely (14%) | 1.63 | 0.71 |

| How often do you worry about getting colon cancer? 1 = rarely or never (71%); 2 = sometimes (25%); 3 = all the time and often (4%) | 1.33 | 0.55 |

| Have any of your brothers, sisters, parents, children, or other close family members ever had cancer? 1 = yes (66%); 0 = no (34%) | 0.66 | 0.47 |

| |||

| The highest grade or year of school an individual completed. 1 = high school graduate or less (49%); 0 = otherwise | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| The highest grade or year of school an individual completed. 1 = some college or technical school (29%); 0 = otherwise | 0.23 | 0.42 |

| The highest grade or year of school an individual completed. 1 = college 4 years and more (27%); 0 = otherwise | 0.26 | 0.44 |

| Socio-Demographic Factors | |||

| What is your age? number of years, minimum = 55, maximum = 95 | 67.92 | 9.20 |

| Are you male or female? 1 = male (37%); 0 = female (63%) | 0.36 | 0.48 |

| Are you married, divorced, widowed, separated, never been married, or a member of an unmarried couple? 1 = married (49%); 0 = others (divorced, widowed, separated, never been married, a member of an unmarried couple) (51%) | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| Which one or more of the following would you say is your race? 1 = Non-Hispanic white (78%); 0 = otherwise | 0.80 | 0.40 |

| Which one or more of the following would you say is your race? 1 = Non-Hispanic black or African American (12%); 0 = otherwise | 0.10 | 0.29 |

| Which one or more of the following would you say is your race? 1 = Hispanic (10%); 0 = otherwise | 0.07 | 0.26 |

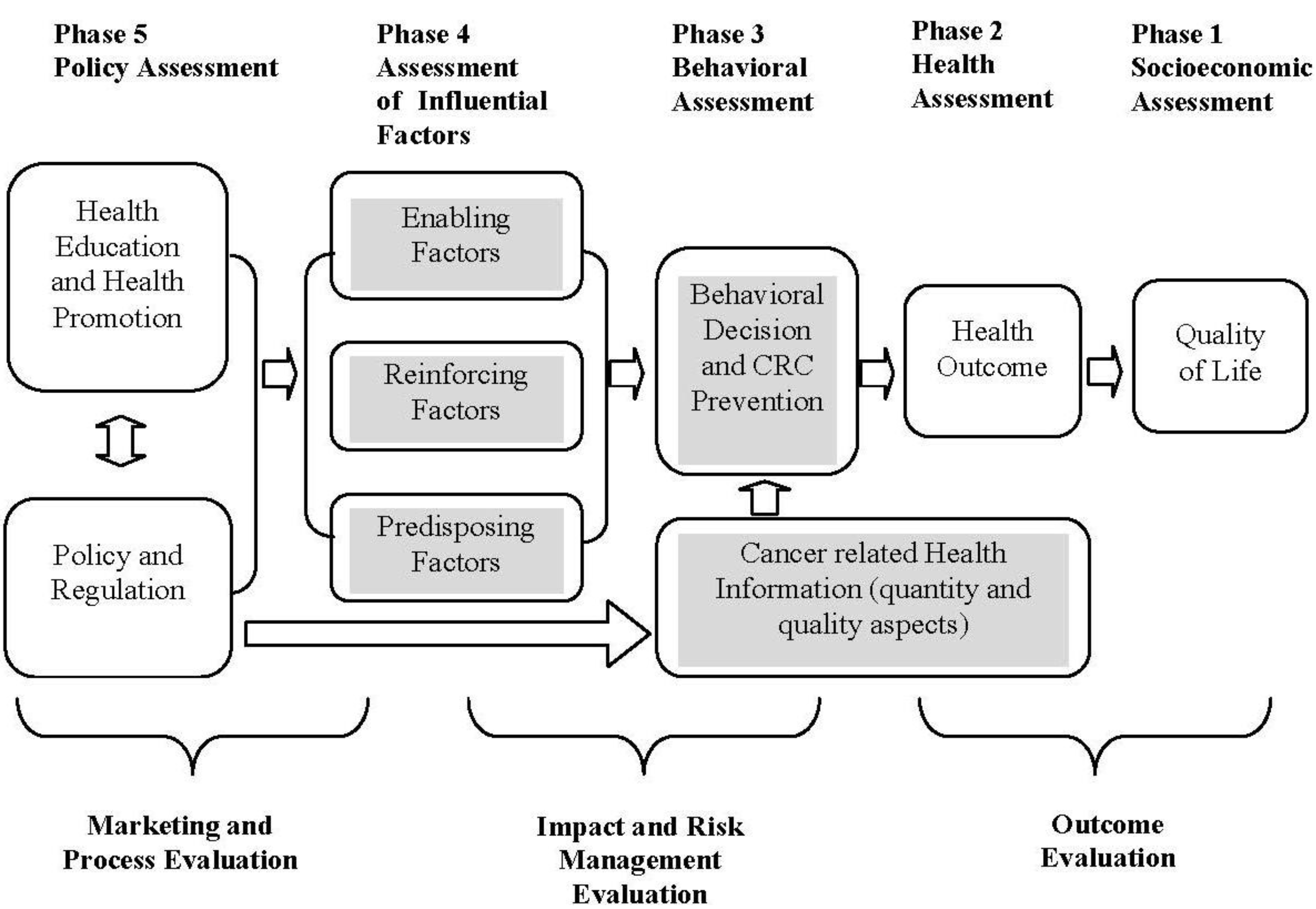

2.2. Empirical Framework

2.3. Statistical Model

i = 1,..., k

3. Results

3.1. Cancer Information Seeking and Access

| Variables | Estimate | p value | Marginal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |||

| |||

| Independent Variables | |||

| Cancer Information Seeking and Access (Quantity Oriented Information) | |||

| 3.252 b | 0.040 | 0.660 b |

| −0.200 | 0.283 | −0.041 |

| −0.490 | 0.129 | −0.099 |

| −0.523 | 0.290 | −0.106 |

| −0.526 | 0.237 | −0.107 |

| Credibility and Reliance of the Cancer Information (Quality Oriented Information) | |||

| 0.737 b | 0.018 | 0.150 b |

| −0.518 c | 0.082 | −0.105 c |

| 0.129 | 0.189 | 0.026 |

| 0.470 c | 0.092 | 0.095 c |

| −0.798 b | 0.016 | −0.162 b |

| 0.695 a | 0.004 | 0.141 a |

| −0.431 b | 0.036 | −0.088 b |

| Enable Factors | |||

| −0.618 | 0.238 | −0.126 |

| 1.945 a | 0.000 | 0.395 a |

| 0.227 c | 0.082 | 0.046 c |

| Reinforcing Factors | |||

| −0.049 | 0.338 | −0.010 |

| Predisposing Factors | |||

| 0.465 a | 0.000 | 0.094 a |

| 0.107 | 0.293 | 0.022 |

| 1.266 a | 0.001 | 0.257 a |

| |||

| −0.039 | 0.922 | −0.008 |

| 0.349 | 0.345 | 0.071 |

| Socio-Demographic Factors | |||

| 0.042 | 0.201 | 0.009 |

| −0.099 | 0.722 | −0.020 |

| −0.319 | 0.369 | −0.065 |

| 1.072 b | 0.020 | 0.217 b |

| −1.526 b | 0.025 | −0.310 b |

| Constant | −4.770 b | 0.050 | −0.968 b |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

3.2. Credibility and Reliance of the Cancer Information

3.3. Enabling, Reinforcing, and Predisposing Factors

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gray, B.H.; Scheinmann, R.; Rosenfeld, P.; Finkelstein, R. Aging without Medicare? Evidence from New York City. Inquiry 2006, 43, 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Strunk, B.C.; Ginsburg, P.B.; Banker, M.I. The effect of population aging on future hospital demand. Health Aff. 2006, 25, w141–w149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinner, K.; Pellegrini, C. Expenditures for public health: Assessing historical and prospective trends. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1780–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Thomas, G.D.; Boseman, L.A.; Beckles, G.L.; Albright, A.L. Aging, diabetes, and the public health system in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1482–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berland, G.K.; Elliott, M.N.; Morales, L.S.; Algazy, J.I.; Kravitz, R.L.; Broder, M.S.; Kanouse, D.E.; Muñoz, J.A.; Puyol, J.A.; Lara, M.; et al. Health information on the Internet: Accessibility, quality, and readability in English and Spanish. JAMA 2001, 285, 2612–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G.; Powell, J.; Kuss, O.; Sa, E.R. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the world wide web: A systematic review. JAMA 2002, 287, 2691–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman-Goetz, L.; Friedman, D.B. A qualitative study of Canadian aboriginal women’s beliefs about “Credible” cancer information on the Internet. J. Cancer Educ. 2007, 22, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustria, M.L.; Smith, S.A.; Hinnant, C.C. Exploring digital divides: An examination of eHealth technology use in health information seeking, communication and personal health information management in the USA. Health Inform. J. 2011, 17, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, M.A. The national cancer institute’s cancer information service: A premiere cancer information and education resource for the nation. J. Cancer Educ. 2007, 22, S2–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, J.F.; Keefe, R.H.; Volpe, F. Use of electronic technologies to promote community and personal health for individuals unconnected to health care systems. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, W.; Lewis, L.S.; Smith, T.L. Health-related message boards/chat rooms on the Web: Discussion content and implications for pharmaceutical sponsorships. J. Health Commun. 2005, 10, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, A.; Chiu, T.; McNaught, C. Screening Internet websites for educational potential in undergraduate medical education. Med. Inform. Internet Med. 2004, 29, 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D.S.; Willicombe, A.; Reid, T.D.; Beaton, C.; Arnold, D.; Ward, J.; Davies, I.L.; Lewis, W.G. Relative quality of Internet-derived gastrointestinal cancer information. J. Cancer Educ. 2012, 27, pp. 676–679. Available online: http://www.springerlink.com/content/k4480832172h1061/ (accessed on 19 August 2012). [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.J.; Ferranti, J. Patient-provider internet portals—Patient outcomes and use. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2011, 29, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.T.; Cohen, G.R. Striking Jump in Consumers Seeking Health Care Information. 2008. Available online: http://hschange.org/CONTENT/1006/1006.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2013).

- Geraghty, A.W.; Torres, L.D.; Leykin, Y.; Pérez-Stable, E.J.; Muñoz, R.F. Understanding attrition from international internet health interventions: A step towards global eHealth. Health Promot. Int. 2012, 28, pp. 442–452. Available online: http://heapro.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2012/07/10/heapro.das029.abstract (accessed on 19 August 2012). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.T.; Bellamy, S.L. Cancer information seeking preferences and experiences: Disparities between Asian Americans and Whites in the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J. Health Commun. 2006, 11, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, B.W.; Nelson, D.E.; Kreps, G.L.; Croyle, R.T.; Arora, N.K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Trust and sources of health information: The impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: Findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 2618–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.Y.; Liu, B.; Post, S.; Hesse, B. Health-related Internet use among cancer survivors: Data from the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2003–2008. J. Cancer Surviv. 2011, 5, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Afaq, F.; Mukhtar, H. Lifestyle as risk factor for cancer: Evidence from human studies. Cancer Lett. 2010, 293, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, S.; Murray, E.; Butler, C.; Wallace, P. Internet-based interactive health intervention for the promotion of sensible drinking: Patterns of use and potential impact on members of the general public. J. Med. Internet Res. 2007, 9, p. e10. Available online: http://www.jmir.org/2007/2/e10/ (accessed on 19 August 2012). [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.D.; Quinn, J.; Quinn, W.; Veledar, E. Surfing the net for medical information about psychological trauma: An empirical study of the quality and accuracy of trauma-related websites. Med. Inform. Internet Med. 2006, 31, 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, E.; Lo, B.; Pollack, L.; Donelan, K.; Catania, J.; Lee, K.; Zapert, K.; Tuner, R. The impact of health information on the Internet on health care and the physician-patient relationship: National U.S. survey among 1,050 U.S. physicians. J. Med. Internet Res. 2003, 5, p. e17. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1550564/ (accessed on 10 January 2012). [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.; Stubbs, D.; Woods, V. Psychological barriers to Internet usage among older adults in the UK. Med. Inform. Internet Med. 2005, 30, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, D.B.; Hoffman-Goetz, L.; Arocha, J.F. Readability of cancer information on the Internet. J. Cancer Educ. 2004, 19, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Basch, C.E.; Yamada, T. An evaluation of colonoscopy use: Implications for health education. J. Cancer Educ. 2010, 25, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.B.; Hoffman-Goetz, L.; Arocha, J.F. Health literacy and the World Wide Web: Comparing the readability of leading incident cancers on the Internet. Med. Inform. Internet Med. 2006, 31, 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Langbecker, D.; Janda, M. Quality and readability of information materials for people with brain tumours and their families. J. Cancer Educ. 2012, 27, pp. 738–743. Available online: http://www.springerlink.com/content/4785837868647377/ (accessed on 19 August 2012). [CrossRef]

- Selman, S.J.; Prakash, T.; Khan, K.S. Quality of health information for cervical cancer treatment on the Internet. BMC Women’s Health. 2006, 6, p. 9. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1550221/ (accessed on 12 June 2012). [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Finkelhor, D.; Becker-Blease, K.A. Classification of adults with problematic internet experiences: Linking Internet and conventional problems from a clinical perspective. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Purcell, K. Chronic Disease and the Internet. 2010. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Chronic_Disease_with_topline.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2012).

- Kiel, J.M. The digital divide: Internet and e-mail use by the elderly. Med. Inform. Internet Med. 2005, 30, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, L. Accessibility compliance rates of consumer-oriented Canadian health care web sites. Med. Inform. Internet Med. 2005, 30, 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2011–2013; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011. Available online: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-028323.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2012).

- DevCan: Probability of Developing or Dying of Cancer Software. Version 6.5.0. Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute, 2005. Available online: http://srab.cancer.gov/devcan (accessed on 15 August 2013).

- Eisen, G.M.; Weinberg, D.S. Narrative review: Screening for colorectal cancer in patients with a first-degree relative with colonic neoplasia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 143, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valantas, M.R.; Farmer, W.M.; DiPalma, J.A. Do gastroenterologists notify polyp patients that family members should have screening? South. Med. J. 2005, 98, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B.; Lieberman, D.A.; McFarland, B.; Smith, R.A.; Brooks, D.; Andrews, K.S.; Dash, C.; Giardiello, F.M.; Glick, S.; Levin, T.R.; et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps: A joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008, 58, 130–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, W.L.; Mansley, E.C.; Gold, K.F.; Wang, Q.; Reddy, P.; Pashos, C.L. Colorectal cancer screening attitudes and practices in the general population: A risk-adjusted survey. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2005, 11, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayyedi, P.; Achkar, E. Does fecal occult blood testing really reduce mortality? A reanalysis of systematic review data. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignone, M.; Rich, M.; Teutsch, S.M.; Berg, A.O.; Lohr, K.N. Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 137, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.; Cokkinides, V.; Eyre, H.J. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2004, 54, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winawer, S.; Fletcher, R.; Rex, D.; Bond, J.; Burt, R.; Ferrucci, J.; Ganiats, T.; Levin, T.; Woolf, S.; Johnson, D.; et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: Clinical guidelines and rationale—Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.E.; Kreps, G.L.; Hesse, B.W.; Croyle, R.T.; Willis, G.; Arora, N.K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K.V.; Weinstein, N.; Alden, S. The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS): Development, design, and dissemination. J. Health Commun. 2004, 9, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, C.E.; Butts, M.; Michels, L. The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria: What did they really say? Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furr, R.M. Evaluating Psychometric Properties: Dimensionality and Reliability. In Scale Construction and Psychometrics for Social and Personality Psychology; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.W.; Kreuter, M.W. Health Program. Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Humanities: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, M. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J. Polit. Econ. 1972, 80, 223–255. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, M. The Demand for Health: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, M. The Human Capital Model. In Handbook of Health Economics, 3rd ed.; Culyer, A.J., Newhouse, J.P., Eds.; Elsevier North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 247–408. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Yamada, T.; Walker, E. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of a classroom-based abstinence and pregnancy avoidance program targeting preadolescent sexual risk behaviors. J. Child. Poverty 2011, 17, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Chen, C.C.; Yamada, T. Economic evaluation for relapse prevention of substance users: Treatment settings and healthcare policy. Adv. Health Econ. Health Serv. Res. 2005, 16, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, A.C.; McDonald, E.M.; Gary, T.L.; Bone, L.R. Using the PRECEDE/PROCEED Model to Apply Health Behavior Theories. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 4th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jessey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 407–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, L. The family as producer of health—An extended Grossman model. J. Health Econ. 2000, 19, 611–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.-C.; Yamada, T.; Smith, J. An Evaluation of Healthcare Information on the Internet: The Case of Colorectal Cancer Prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 1058-1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110101058

Chen C-C, Yamada T, Smith J. An Evaluation of Healthcare Information on the Internet: The Case of Colorectal Cancer Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(1):1058-1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110101058

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Chia-Ching, Tetsuji Yamada, and John Smith. 2014. "An Evaluation of Healthcare Information on the Internet: The Case of Colorectal Cancer Prevention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 1: 1058-1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110101058

APA StyleChen, C.-C., Yamada, T., & Smith, J. (2014). An Evaluation of Healthcare Information on the Internet: The Case of Colorectal Cancer Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(1), 1058-1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110101058