Maternal Factors and Utilization of the Antenatal Care Services during Pregnancy Associated with Low Birth Weight in Rural Nepal: Analyses of the Antenatal Care and Birth Weight Records of the MATRI-SUMAN Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population, and Sampling

2.2. Definition of Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

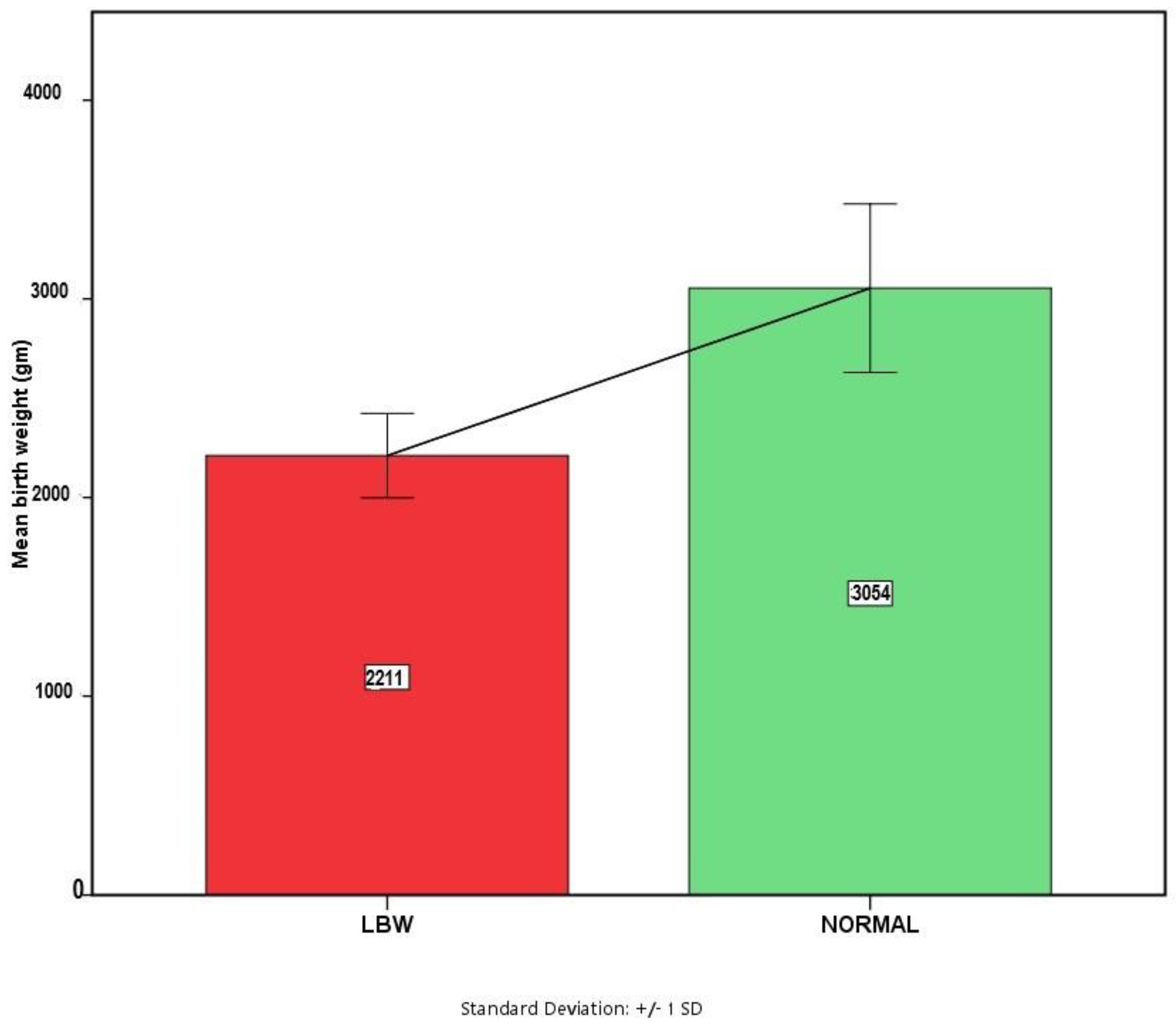

3.1. Status of Birth Weight

3.2. Maternal Factors and Utilization of Antenatal Care Services

3.3. Associations between Low Birth Weight and Maternal Factors and the Utilization of Antenatal Care Services

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wardlaw, T.M. Low Birthweight: Country, Regional and Global Estimates; Unicef: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Low Birhtweight. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/low-birthweight/ (accessed on 27 October 2018).

- Singh, U.; Ueranantasun, A.; Kuning, M. Factors associated with low birth weight in nepal using multiple imputation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Zupan, J. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet 2005, 365, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, F.C.; Barros, A.J.; Villar, J.; Matijasevich, A.; Domingues, M.R.; Victora, C.G. How many low birthweight babies in low- and middle-income countries are preterm? Rev. Saude Publica 2011, 45, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, M.S. Intrauterine growth and gestational duration determinants. Pediatrics 1987, 80, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qadir, M.; Bhutta, Z.A. Low birth weight in developing countries. In Small for Gestational Age; Karger Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2009; Volume 13, pp. 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Alderman, H.; Behrman, J.R. Reducing the incidence of low birth weight in low-income countries has substantial economic benefits. World Bank Res. Obs. 2006, 21, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Srinivasan, S.R.; Yao, L.; Li, S.; Dasmahapatra, P.; Fernandez, C.; Xu, J.; Berenson, G.S. Low birth weight is associated with higher blood pressure variability from childhood to young adulthood: The bogalusa heart study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 1, S99–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, J.E. The nutritional basis of the fetal origins of adult disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ediriweera, D.S.; Dilina, N.; Perera, U.; Flores, F.; Samita, S. Risk of low birth weight on adulthood hypertension—Evidence from a tertiary care hospital in a south asian country, sri lanka: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larroque, B.; Bertrais, S.; Czernichow, P.; Leger, J. School difficulties in 20-year-olds who were born small for gestational age at term in a regional cohort study. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risnes, K.R.; Vatten, L.J.; Baker, J.L.; Jameson, K.; Sovio, U.; Kajantie, E.; Osler, M.; Morley, R.; Jokela, M.; Painter, R.C.; et al. Birthweight and mortality in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, P.; Murray-Kolb, L.E.; Tielsch, J.M.; Katz, J.; LeClerq, S.C.; Khatry, S.K. Associations between preterm birth, small-for-gestational age, and neonatal morbidity and cognitive function among school-age children in nepal. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashish, K.C.; Nelin, V.; Wrammert, J.; Ewald, U.; Vitrakoti, R.; Baral, G.N.; Malqvist, M. Risk factors for antepartum stillbirth: A case-control study in nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M.S. Determinants of low birth weight: Methodological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull. World Health Organ. 1987, 65, 663–737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sebayang, S.K.; Dibley, M.J.; Kelly, P.J.; Shankar, A.V.; Shankar, A.H.; Group, S.S. Determinants of low birthweight, small-for-gestational-age and preterm birth in lombok, indonesia: Analyses of the birthweight cohort of the summit trial. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2012, 17, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gizaw, B.; Gebremedhin, S. Factors associated with low birthweight in north shewa zone, central ethiopia: Case-control study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, 44, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, V.; Sauer, K.; Karkee, R.; Zhao, Y. Factors associated with small size at birth in nepal: Further analysis of nepal demographic and health survey 2011. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, V.; Zhao, Y.; Sauer, K. Role of antenatal care and iron supplementation during pregnancy in preventing low birth weight in nepal: Comparison of national surveys 2006 and 2011. Arch. Public Health 2014, 72, 2049–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Population; New ERA; ICF International. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011; Ministry of Health and Population; New ERA: Kathmandu, Nepal; ICF International: Calverton, MD, USA, 2012.

- Ministry of Health and Population; New ERA; ICF International. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016; Ministry of Health and Population; New ERA: Kathmandu, Nepal; ICF International: Calverton, MD, USA, 2017.

- Singh, J.K.; Kadel, R.; Acharya, D.; Lombard, D.; Khanal, S.; Singh, S.P. ‘Matri-suman’ a capacity building and text messaging intervention to enhance maternal and child health service utilization among pregnant women from rural nepal: Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.K.; Acharya, D.; Kadel, R.; Adhikari, S.; Lombard, D.; Koirala, S.; Paudel, R. Factors associated with smokeless tobacco use among pregnant women in rural areas of the southern terai, nepal. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2017, 15, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, L.; Dahal, D.R.; Govindasamy, P. Caste ethnic and regional identity in nepal: Further analysis of the 2006 nepal demographic and health survey. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FA58/FA58.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2018).

- Collins, J.W., Jr.; David, R.J. The differential effect of traditional risk factors on infant birthweight among blacks and whites in chicago. Am. J. Public Health 1990, 80, 679–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Madhavan, S.; Alderman, M.H. Low birth weight: Race and maternal nativity—Impact of community income. Pediatrics 1999, 103, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinman, J.C.; Kessel, S.S. Racial differences in low birth weight. Trends and risk factors. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakewell, J.M.; Stockbauer, J.W.; Schramm, W.F. Factors associated with repetition of low birthweight: Missouri longitudinal study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 1997, 11 (Suppl. 1), 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.P.; Alpass, F. Birth outcomes across ethnic groups of women in nepal. Health Care Women Int. 2004, 25, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, N. Maternal factors for low birth weight and preterm birth at tertiary care hospital. J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2015, 53, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.A.; Greenow, C.R.; Ariff, S.; Soofi, S.; Hussain, A.; Junejo, Q.; Hussain, A.; Shaheen, F.; Black, K.I. Factors associated with low birthweight in term pregnancies: A matched case-control study from rural pakistan. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 23, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Mu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; Scherpbier, R.; Guo, S.; Huang, X.; et al. Low birthweight in china: Evidence from 441 health facilities between 2012 and 2014. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 30, 1997–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, S.K.; Howlader, M.H.; Nahar, N. Educational status of the married women and their participation at household decision making in rural bangladesh. Int. J. Adv. Res. Technol. 2012, 1, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cribb, V.L.; Jones, L.R.; Rogers, I.S.; Ness, A.R.; Emmett, P.M. Is maternal education level associated with diet in 10-year-old children? Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2037–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Hu, W.; Luo, X.; Shen, Y. Interaction of prenatal care and level of maternal education on the risk of neonatal low birth weight. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2014, 35, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bates, L.M.; Maselko, J.; Schuler, S.R. Women’s education and the timing of marriage and childbearing in the next generation: Evidence from rural bangladesh. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2007, 38, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Khanal, V.; Singh, J.K.; Adhikari, M.; Gautam, S. Impact of mass media on the utilization of antenatal care services among women of rural community in nepal. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, K.; Agarwal, A.; Agrawal, V.; Agrawal, P.; Chaudhary, V. Prevalence and determinants of “low birth weight” among institutional deliveries. Ann. Niger. Med. 2011, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickute, J.; Padaiga, Z.; Grabauskas, V.; Gaizauskiene, A.; Basys, V.; Obelenis, V. Do maternal social factors, health behavior and work conditions during pregnancy increase the risk of low birth weight in lithuania? Medicina 2002, 38, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.R.; Giri, S.; Timalsina, U.; Bhandari, S.S.; Basyal, B.; Wagle, K.; Shrestha, L. Low birth weight at term and its determinants in a tertiary hospital of nepal: A case-control study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurewicz, J.; Hanke, W.; Makowiec-Dabrowska, T.; Kalinka, J. Heaviness of the work measured by energy expenditure during pregnancy and its effect on birth weight. Ginekol. Pol. 2006, 77, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bener, A.; Abdulrazzaq, Y.M.; Dawodu, A. Sociodemographic risk factors associated with low birthweight in united arab emirates. J. Biosoc. Sci. 1996, 28, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, Y.; Hotchkiss, D.R. The socio-economic determinants of maternal health care utilization in turkey. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, U. Nutrition and low birth weight: From research to practice. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Kader, M. Effect of women’s decision-making autonomy on infant’s birth weight in rural bangladesh. ISRN Pediatr. 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchemi, O.M.; Echoka, E.; Makokha, A. Factors associated with low birth weight among neonates born at olkalou district hospital, central region, kenya. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugssa, G.; Alemayehu, M.; Dimtsu, B. Socio demographic and maternal determinants of low birth weight at mekelle hospital, northern ethiopia: A cross sectional study. Open J. Adv. Drug Deliv. 2014, 2, 609–618. [Google Scholar]

- Asmare, G.; Berhan, N.; Berhanu, M.; Alebel, A. Determinants of low birth weight among neonates born in amhara regional state referral hospitals of ethiopia: Unmatched case control study. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herceg, A.; Simpson, J.M.; Thompson, J.F. Risk factors and outcomes associated with low birthweight delivery in the australian capital territory 1989–90. J. Paediatr. Child Health 1994, 30, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.A. The evolution of dominance. Biol. Rev. 1931, 6, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdi, T.J.; Shah, S.U. Implementing perennial kitchen garden model to improve diet diversity in melghat, India. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2016, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, V.; Scott, J.A.; Lee, A.H.; Karkee, R.; Binns, C.W. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding in western nepal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9562–9574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, P.; Khatry, S.K.; West, K.P., Jr. Antenatal anthelmintic treatment, birthweight, and infant survival in rural nepal. Lancet 2004, 364, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocque, R.; Casapia, M.; Gotuzzo, E.; MacLean, J.D.; Soto, J.C.; Rahme, E.; Gyorkos, T.W. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of antenatal mebendazole to reduce low birthweight in a hookworm-endemic area of peru. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2006, 11, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Ni, Z.M.; Wang, G.; Liu, S.Y.; Li, C.; Yu, C.L.; Wang, Q.; Nie, S.F. Risk factors for low birth weight and preterm birth: A population-based case-control study in wuhan, china. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2017, 37, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakya, K.L.; Shrestha, N.; Kisiju, P.; Onta, S.R. Association of maternal factors with low birth weight in selected hospitals of nepal. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2015, 13, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Shaker El-Sayed Azzaz, A.; Martinez-Maestre, M.A.; Torrejon-Cardoso, R. Antenatal care visits during pregnancy and their effect on maternal and fetal outcomes in pre-eclamptic patients. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2016, 42, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.E.; Fraser-Lee, N.J.; Tough, S.; Newburn-Cook, C.V. The content of prenatal care and its relationship to preterm birth in alberta, canada. Health Care Women Int. 2006, 27, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogswell, M.E.; Parvanta, I.; Ickes, L.; Yip, R.; Brittenham, G.M. Iron supplementation during pregnancy, anemia, and birth weight: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urassa, D.P.; Nystrom, L.; Carlsted, A. Effectiveness of routine antihelminthic treatment on anaemia in pregnancy in rufiji district, tanzania: A cluster randomised controlled trial. East Afr. J. Public Health 2011, 8, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lechtig, A.; Habicht, J.P.; Delgado, H.; Klein, R.E.; Yarbrough, C.; Martorell, R. Effect of food supplementation during pregnancy on birthweight. Pediatrics 1975, 56, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.; Ismail, S.; Ashworth, A.; Morris, S.S. Influence of heavy agricultural work during pregnancy on birthweight in northeast brazil. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1999, 28, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defo, B.K.; Partin, M. Determinants of low birthweight: A comparative study. J. Biosoc. Sci. 1993, 25, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimmer, I.; Buhrer, C.; Dudenhausen, J.W.; Stroux, A.; Reiher, H.; Halle, H.; Obladen, M. Preconceptional factors associated with very low birthweight delivery in east and west berlin: A case control study. BMC Public Health 2002, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, A.K.; Bhatta, D.N. Low-birth-weight babies among hospital deliveries in nepal: A hospital-based study. Int. J. Womens Health 2015, 7, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | n = 402 (%) | Low Birth Weight | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n = 78 (%) | No, n = 324 (%) | |||

| Age | ||||

| <20 year | 91 (22.6) | 20 (25.6) | 71 (21.9) | 0.674 |

| 20-34 year | 278 (69.2) | 53 (67.9) | 225 (69.5) | |

| ≥35 years | 33 (8.2) | 5 (6.4) | 28 (8.6) | |

| Caste/ethnicity | ||||

| Upper caste group | 246 (61.2) | 27 (34.6) | 219 (67.6) | <0.0001 |

| Adibasi/Janajati | 89 (22.1) | 19 (24.4) | 70 (21.6) | |

| Dalit | 67 (16.7) | 32 (41.0) | 35 (10.8) | |

| Educational status | ||||

| Illiterate | 100 (24.8) | 46 (59.0) | 54 (16.7) | <0.0001 |

| Primary | 145 (36.1) | 21 (26.9) | 124 (38.3) | |

| Secondary and above | 157 (39.1) | 11 (14.1) | 146 (45.0) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Labor | 75 (18.7) | 36 (46.2) | 39 (12.0) | <0.0001 |

| Agricultural work | 127 (31.6) | 24 (30.8) | 103 (31.8) | |

| Service/business/HH works | 200 (49.8) | 18 (23.0) | 182 (56.2) | |

| Family income | ||||

| 1st tercile | 138 (34.3) | 39 (50.0) | 99 (30.5) | <0.0001 |

| 2nd tercile | 128 (31.8) | 26 (33.3) | 102 (31.5) | |

| 3rd tercile | 136 (33.8) | 13 (16.7) | 123 (38.0) | |

| Head of family | ||||

| Herself | 90 (22.4) | 10 (12.8) | 80 (24.7) | 0.024 |

| Others (In-laws/ Husband) | 312 (77.6) | 68 (87.2) | 244 (75.3) | |

| Resided in MATRI-SUMAN intervention area | ||||

| Yes | 207 (51.5) | 31 (39.7) | 176 (54.3) | 0.021 |

| No | 195 (48.5) | 47 (60.3) | 148 (45.7) | |

| Origin of residence | ||||

| Terai | 288 (71.6) | 51 (65.4) | 237 (73.1) | 0.172 |

| Hill | 114 (28.4) | 27 (34.6) | 87 (26.9) | |

| Dietary habit | ||||

| Non-vegetarian | 320 (79.6) | 63 (80.8) | 257 (79.3) | 0.776 |

| Vegetarian | 82 (20.4) | 15 (19.2) | 67 (20.7) | |

| Parity | ||||

| Primi | 157 (39.1) | 22 (28.2) | 135 (41.7) | 0.029 |

| Multi | 245 (60.9) | 56 (71.8) | 189 (58.3) | |

| Sex of Child | ||||

| Male | 191 (47.5) | 28 (35.9) | 163 (50.3) | 0.022 |

| Female | 211 (52.5) | 50 (64.1) | 161 (49.7) | |

| Family size | ||||

| 4 and less person | 212 (52.7) | 12 (15.4) | 200 (61.7) | <0.0001 |

| >4 persons | 190 (47.3) | 66 (84.6) | 124 (38.3) | |

| Living room in family | ||||

| Insufficient | 176 (43.8) | 57 (73.1) | 119 (36.7) | <0.0001 |

| Sufficient | 226 (56.2) | 21 (26.9) | 205 (63.3) | |

| Domestic animals | ||||

| Yes | 159 (39.6) | 25 (32.1) | 134 (41.4) | 0.131 |

| No | 243 (60.4) | 53 (67.9) | 190 (58.6) | |

| Kitchen garden | ||||

| Yes | 267 (66.4) | 19 (24.4) | 248 (76.5) | <0.0001 |

| No | 135 (33.6) | 59 (75.6) | 76 (23.5) | |

| Variables | n = 402 (%) | Low Birth Weight | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n = 78 (%) | No, n = 324 (%) | |||

| ANC visit-end | ||||

| No | 35 (8.7) | 14 (17.9) | 21 (6.5) | 0.002 |

| <4ANC | 127 (31.6) | 29 (37.2) | 98 (30.2) | |

| 4 or More | 240 (59.7) | 35 (44.9) | 205 (63.3) | |

| Consumption of recommended dose of Iron and folic acid (IFA) | ||||

| Yes | 235 (58.5) | 34 (43.6) | 201 (62.0) | 0.003 |

| No | 167 (41.5) | 44 (56.4) | 123 (38.0) | |

| Immunized with recommended dose of Tetanus and diphtheria (TD) | ||||

| Yes | 328 (81.6) | 48 (61.6) | 280 (86.4) | <0.0001 |

| No | 74 (18.4) | 30 (38.4) | 44 (13.6) | |

| Consumed de-worming tablet | ||||

| Yes | 327 (81.3) | 47 (60.3) | 280 (86.4) | <0.0001 |

| No | 75 (18.7) | 31 (39.7) | 44 (13.6) | |

| Adequate rest and sleep taken | ||||

| SYes | 339 (84.3) | 59 (75.6) | 280 (86.4) | 0.019 |

| No | 63 (15.7) | 19 (24.4) | 44 (13.6) | |

| Additional food intake | ||||

| Yes | 99 (24.6) | 47 (60.3) | 52 (16.0) | <0.0001 |

| No | 303 (75.4) | 31 (39.7) | 272 (84.0) | |

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal factors | ||||

| Intervention area | ||||

| Yes | 0.55 (0.34–1.0) | 0.022 | 0.37 (0.16–0.83) | 0.009 |

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Caste/ethnicity | ||||

| Dalit | 7.4 (3.9–13.8) | 0.0001 | 4.2 (1.7–10.4) | 0.0001 |

| Adibasi/Janajati | 2.2 (1.1–4.2) | 0.0001 | 1.8 (0.8–5.1) | 0.216 |

| Upper caste group | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Educational status | ||||

| Illiterate | 11.3 (5.4–23.4) | 0.0001 | 8.1 (2.9–22.4) | 0.0001 |

| Primary | 2.2 (1.0–4.8) | 0.0001 | 1.6 (0.9–8.6) | 0.217 |

| Secondary and above | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Occupation | ||||

| Labor | 9.3 (4.8–18.1) | 0.001 | 5.9 (1.6–21.1) | 0.006 |

| Agricultural work | 2.3 (1.2–4.5) | 0.011 | 1.7 (0.5–5.3) | 0.332 |

| Service/ business/ HH works | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Family income | ||||

| 1st tercile | 3.7 (1.8–7.3) | 0.0001 | 1.1 (0.5–2.9) | 0.761 |

| 2nd tercile | 2.4 (1.1–4.9) | 0.016 | 1.4 (0.3–1.9) | 0.618 |

| 3rd tercile | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Head of family | ||||

| Others (In-laws/ Husband) | 2.2 (1.0–4.5) | 0.027 | 1.9 (0.6–5.5) | 0.206 |

| Herself | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Parity | ||||

| Multi | 1.8 (1.0–3.1) | 0.030 | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 0.758 |

| Primi | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Sex of child | ||||

| Female | 1.8 (1.0–3.0) | 0.023 | 2.0 (1.0–4.1) | 0.047 |

| Male | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Family size | ||||

| >4 persons | 8.8 (4.6–17.0) | <0.0001 | 5.6 (2.3–13.5) | <0.0001 |

| 4 and less person | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Living room in family | ||||

| Insufficient | 5.0 (2.9–8.8) | <0.0001 | 1.2 (0.4–3.5) | 0.664 |

| Sufficient | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Kitchen garden | ||||

| Yes | 0.09 (0.05–0.17) | <0.0001 | 0.15 (0.06–0.37) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Utilization of antenatal care services during pregnancy | ||||

| ANC visit | ||||

| No | 3.9 (1.8–8.3) | <0.0001 | 5.1 (1.1–22.6) | 0.029 |

| <4ANC | 1.7 (1.0–3.0) | <0.0010 | 3.4 (1.1–10.2) | 0.027 |

| 4 and more ANC | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Consumption of recommended dose of Iron and folic acid (IFA) | ||||

| No | 2.1 (1.2–3.4) | 0.003 | 3.0 (1.1–8.2) | 0.025 |

| Yes | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Immunized with recommended dose of Tetanus and diphtheria (TD) | ||||

| No | 3.9 (2.2–6.9) | 0.0001 | 2.2 (0.5–10.0) | 0.295 |

| Yes | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Consumed de-worming tablet | ||||

| No | 4.1 (2.4–7.3) | 0.0001 | 3.1 (1.0–13.8) | 0.049 |

| Yes | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Adequate rest and sleep taken | ||||

| No | 2.0 (1.1–3.7) | 0.020 | 1.5 (0.5–4.8) | 0.412 |

| Yes | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

| Additional food intake | ||||

| No | 7.9 (4.6–13.6) | 0.0001 | 3.6 (1.3–9.4) | 0.008 |

| Yes | 1.0 (ref.) | - | 1.0 (ref.) | - |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acharya, D.; Singh, J.K.; Kadel, R.; Yoo, S.-J.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, K. Maternal Factors and Utilization of the Antenatal Care Services during Pregnancy Associated with Low Birth Weight in Rural Nepal: Analyses of the Antenatal Care and Birth Weight Records of the MATRI-SUMAN Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112450

Acharya D, Singh JK, Kadel R, Yoo S-J, Park J-H, Lee K. Maternal Factors and Utilization of the Antenatal Care Services during Pregnancy Associated with Low Birth Weight in Rural Nepal: Analyses of the Antenatal Care and Birth Weight Records of the MATRI-SUMAN Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(11):2450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112450

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcharya, Dilaram, Jitendra Kumar Singh, Rajendra Kadel, Seok-Ju Yoo, Ji-Hyuk Park, and Kwan Lee. 2018. "Maternal Factors and Utilization of the Antenatal Care Services during Pregnancy Associated with Low Birth Weight in Rural Nepal: Analyses of the Antenatal Care and Birth Weight Records of the MATRI-SUMAN Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 11: 2450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112450

APA StyleAcharya, D., Singh, J. K., Kadel, R., Yoo, S.-J., Park, J.-H., & Lee, K. (2018). Maternal Factors and Utilization of the Antenatal Care Services during Pregnancy Associated with Low Birth Weight in Rural Nepal: Analyses of the Antenatal Care and Birth Weight Records of the MATRI-SUMAN Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112450