Patient Satisfaction with Pre-Hospital Emergency Services. A Qualitative Study Comparing Professionals’ and Patients’ Views

Abstract

:1. Introduction

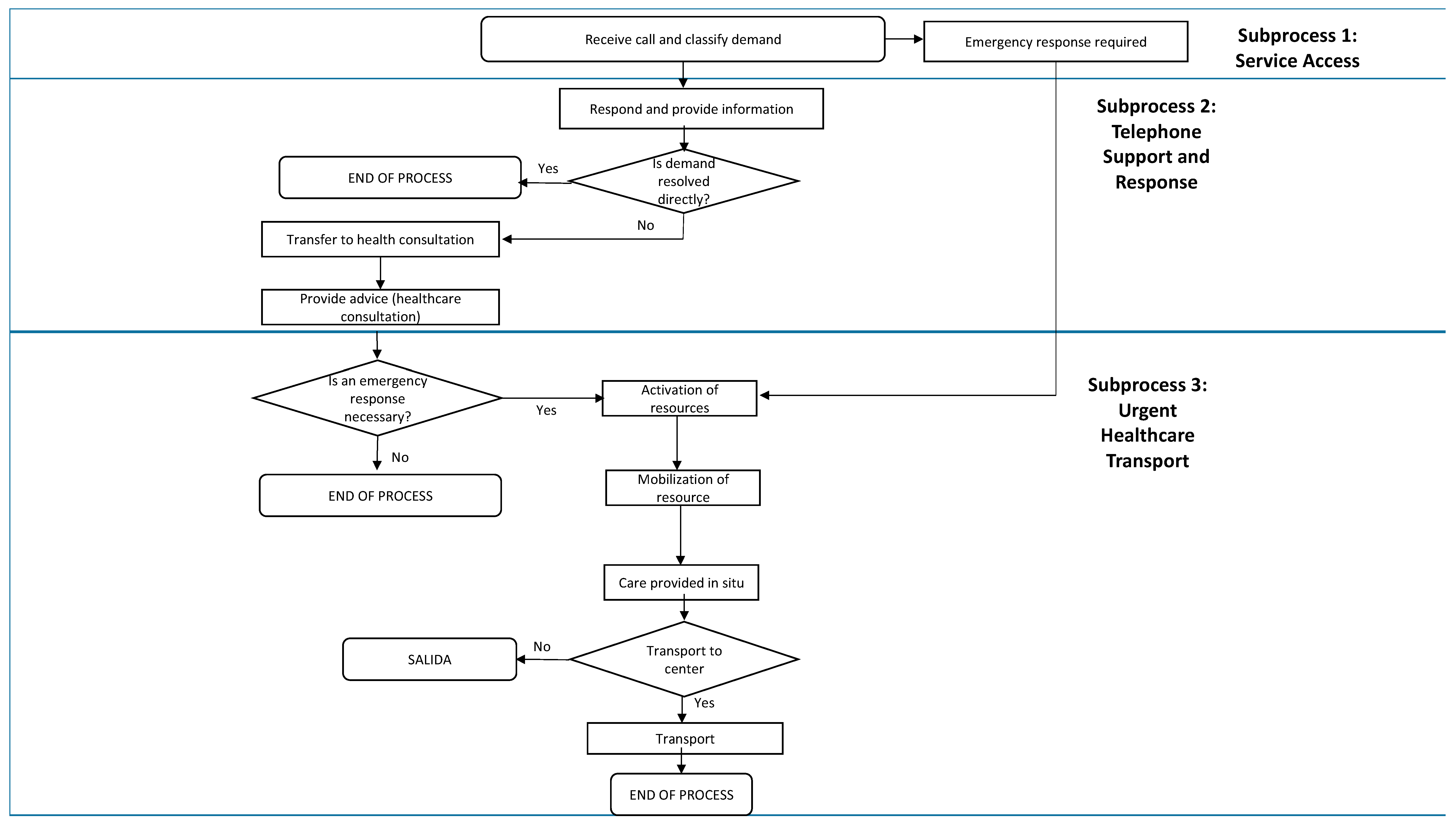

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. First Phase: Literature Review

2.2. Second Phase: Qualitative Research

2.3. Perception of Professionals

2.4. Perception of Patients

3. Results

3.1. First Phase: Literature Review

3.2. Second Phase: Qualitative Research

3.2.1. Accessibility

3.2.2. Response Capacity

3.2.3. Professionalism

3.2.4. Transport Conditions

3.2.5. Capacity for Resolving the Situation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koos, E. The Health of Regionsville; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 1966, 44, 166–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, R. Surveillance and monitoring. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1974, 3, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder-Pelz, S. Social psychological determinants of patient satisfaction: A test of five hypotheses. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982, 16, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzia, J. How valid and reliable are patient satisfaction data? An analysis of 195 studies. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1999, 11, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, J.J. La satisfacción del paciente: Teorías, medidas y resultados. Todo Hosp. 2006, 224, 90–97. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.; Dornan, M. What patients like about their medical care and how often they are asked: A meta-analysis of the satisfaction literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 1988, 27, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicios de Urgencias y Emergencias 112/061. Datos 2015. Available online: http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/SIAP/Estadisticas.htm (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Hadsund, J.; Riiskjær, E.; Riddervold, I.S.; Christensen, E.F. Positive patients’ attitudes to pre-hospital care. Dan. Med. J. 2013, 60, A4694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swain, A.H.; Al-Salami, M.; Hoyle, S.R.; Larsen, P.D. Patient satisfaction and outcome using emergency care practitioners in New Zealand. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2012, 24, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisah, A.; Chew, K.S.; Mohd Shaharuddin Shah, C.H.; Nik Hisamuddin, N.A. Patients’ perception of the ambulance services at Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. Singap. Med. J. 2008, 49, 631–635. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, S.; Knowles, E.; Colwell, B.; Dixon, S.; Wardrope, J.; Gorringe, R.; Snooks, H.; Perrin, J.; Nicholl, J. Effectiveness of paramedic practitioners in attending 999 calls from elderly people in the community: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007, 335, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.W.; Lindsell, C.J.; Handel, D.A.; Collett, L.; Gallo, P.; Kaiser, K.D.; Locasto, D. Postal survey methodology to assess patient satisfaction in a suburban emergency medical services system: An observational study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2007, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, P. Ambulance satisfaction surveys: Their utility in policy development, system change and professional practice. JEPHC 2003, 1, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Persee, D.E.; Key, C.B.; Baldwin, J.B. The effect of a quality improvement feedback loop on paramedic-initiated nontransport of elderly patients. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2002, 6, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Neumayr, A.; Gnirke, A.; Schaeuble, J.C.; Ganter, M.T.; Sparr, H.; Zoll, A.; Schinnerl, A.; Nuebling, M.; Heidegger, T.; Baubin, M. Patient satisfaction in out-of-hospital emergency care: A multicenter survey. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.; Coster, J.; Chambers, D.; Cantrell, A.; Phung, V.-H.; Knowles, E.; Bradbury, D.; Goyder, E. What Evidence Is There on the Effectiveness of Different Models of Delivering Urgent care? A Rapid Review; School for Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Booker, M.J.; Shaw, A.R.G.; Purdy, S. Why do patients with ‘primary care sensitive’ problems access ambulance services? A systematic mapping review of the literature. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamam, A.F.; Bagis, M.H.; AlJohani, K.; Tashkandi, A.H. Public awareness of the EMS system in Western Saudi Arabia: Identifying the weakest link. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togher, F.J.; O’Cathain, A.; Phung, V.H.; Turner, J.; Siriwardena, A.N. Reassurance as a key outcome valued by emergency ambulance service users: A qualitative interview study. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 2951–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronsson, K.; Björkdahl, I.; Wireklint Sundström, B. Pre-hospital emergency care for patients with suspected hip fractures after falling—Older patients’ experiences. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 3115–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kietzmann, D.; Wiehn, S.; Kehl, D.; Knuth, D.; Schmidt, S. Migration background and overall satisfaction with pre-hospital emergency care. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 29, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keene, T.; Davis, M.; Brook, C. Characteristics and outcomes of patients assessed by paramedics and not transported to hospital: A pilot study. Australas. J. Paramed. 2015, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Studnek, J.R.; Fernandez, A.R.; Vandeventer, S.; Davis, S.; Garvey, L. The association between patients’ perception of their overall quality of care and their perception of pain management in the pre-hospital setting. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2013, 17, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togher, F.J.; Davy, Z.; Siriwardena, A.N. Patients’ and ambulance service clinicians’ experiences of pre-hospital care for acute myocardial infarction and stroke: A qualitative study. Emerg. Med. J. 2013, 30, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, A.; Ekwall, A.; Wihlborg, J. Patient satisfaction with ambulance care services: Survey from two districts in Southern Sweden. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2011, 19, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A.; Knowles, E.; Turner, J.; Nicholl, J. Acceptability of NHS 111 the telephone service for urgent health care: Cross sectional postal survey of users’ views. Fam. Pract. 2014, 31, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasqueiro, S.; Oliveira, M.; Encarnação, P. Evaluation of telephone triage and advice services: A systematic review on methods, metrics and results. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2011, 169, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ström, M.; Marklund, B.; Hildingh, C. Callers’ perceptions of receiving advice via a medical care help line. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2009, 23, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, C.; Soriano, F.; Morant, F. Análisis de la calidad percibida por los usuarios externos de la Unidad de Coordinación de Transporte Sanitario no Asistido de Alicante. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2011, 26, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, R.; Humphreys, J. Evaluation of a telephone advice nurse in a nursing Managed pediatric community clinic. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2008, 22, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.; Avies-Jones, A. An audit of the NICE self-harm guidelines at a local accident and emergency department in North Wales. Accid. Emerg. Nurs. 2007, 15, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.; O’Keeffe, C.; Coleman, P.; Edlin, R.; Nicholl, J. Effectiveness of emergency care practitioners working within existing emergency service models of care. Emerg. Med. J. 2007, 24, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halter, M.; Marlow, T.; Tye, C.; Ellison, G.T. Patients’ experiences of care provided by emergency care practitioners and traditional ambulance practitioners: A survey from the London Ambulance Service. Emerg. Med. J. 2006, 23, 865–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forslund, K.; Kihlgren, M.; Ostman, I.; Sørlie, V. Patients with acute chest pain—Experiences of emergency calls and pre-hospital care. J. Telemed. Telecare 2005, 11, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.; O’Keeffe, C.; Coleman, P.; Edlin, R.; Nicholl, J. A National Evaluation of the Clinical and Cost Effectiveness of Emergency Care Practitioners; 2005 Medical Care Research Unit (MCRU); University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Machen, I.; Dickinson, A.; Williams, J.; Widiatmoko, D.; Kendall, S. Nurses and paramedics in partnership: Perceptions of a new response to low-priority ambulance calls. Accid. Emerg. Nurs. 2007, 15, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snooks, H.; Kearsley, N.; Dale, J.; Halter, M.; Redhead, J.; Cheung, W.Y. Towards primary care for non-serious 999 callers: Results of a controlled study of “Treat and Refer” protocols for ambulance crews. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2004, 13, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cariello, F.P. Computerized Telephone Nurse Triage. An Evaluation of Service Quality and Cost. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2003, 26, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A.; Turner, J.; Nicholl, J.P. The acceptability of an emergency medical dispatch system to people who call 999 to request an ambulance. Emerg. Med. J. 2002, 19, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A.; Munro, J.F.; Nicholl, J.P.; Knowles, E. How helpful is NHS Direct? Postal survey of callers. BMJ 2000, 320, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, J.M.; González, N.; Bilbao, A.; Aizpuru, F.; Escobar, A.; Esteban, C.; San-Sebastián, J.A.; de-la-Sierra, E.; Thompson, A. Predictors of patient satisfaction with hospital health care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, J.J.; Tomás, O.; Pérez-Jover, V.; Nebot, C.; Rodríguez-Marin, J. Predictors of patient satisfaction in surgery. Surgery 2009, 145, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petek, D.; Kersnik, J.; Szecsenyl, J.; Wensing, M. Patients’ evaluations of European general practice—Revisited after 11 years. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2011, 23, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjertnaes, O.A.; Strømseng Sjetne, I.; Iversen, H. Overall patient satisfaction with hospitals: Effects of patient-reported experiences and fulfilment of expectations. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2012, 21, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Yes | Country | Objective | Measurement Method | N | Dimensions Assessed of the Perceived Quality | Most Relevant Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 [16] | Austria and Switzerland | Evaluate patient satisfaction regarding the call, treatment, transport, and hospital admission into the emergency medical service in Austria and Switzerland. | Survey, multicentric study | Austria: 291 (response rate, 44.5%) Switzerland: 240 (response rate, 49.7%) Total: 531 (response rate, 46.7%) | 4 dimensions: emergency call, emergency treatment, transport, and hospital admission. 48 quality indicators: wait time, time dedicated to patient, treatment, skills of healthcare personnel (medical, emotional, listening, social, education, friendliness), cordiality, professionalism, treatment efficacy (pain relief), information, decision making, culture, intimacy, comfort during transport, safety during transport. | In 91.7% of cases, the general satisfaction with the emergency treatment obtained a very high score (between 90 and 100 points). The average scores in all quality criteria evaluated exceeded 90 points (out of 100) except for some items referring to the social skills of healthcare professionals (85.8 medical, 84.8 emotional, 86.3 listening, 83.3 social). |

| 2015 [17] | United Kingdom | Assessment of the quality and safety of emergency care. | Systematic review | 45 reviews and 102 empirical studies | -- | Satisfaction with telephone triage varied between 55–97%. Dissatisfaction between 2.3–18.3% was greater when patients expected to be supplied with an ambulance. There was less satisfaction with nurses than with physicians. |

| >2015 [18] | >United Kingdom | Review of studies on ambulance use by primary care patients. | Systematic review | Of 31 studies, 1 study satisfaction | -- | Satisfaction decreases sequentially depending upon the number of different services that establish contact with the patient before receiving definitive care. |

| 2015 [19] | Saudi Arabia | Degree of knowledge of the emergency service in Jeddah. | Survey in public places | 1534 residents of the city of Jeddah | Knowledge of the number to call, ambulance request, time for ambulance to arrive, preference for a single centralized telephone number or one for each service, confidence of the paramedics in the treatment performed, coverage, trust, whether a male may attend to a female patient without a male relative present. | 22% considered ambulance coverage adequate. 32% waited less than 30 min for the ambulance. 18% considered that if no male was within the residence, nobody could enter it to provide care for a female. |

| 2014 [20] | United Kingdom | Aspects that ambulance users value. | Interview: personal (n = 18) and telephone (n = 12) | 22 patients and 8 wives (n = 30) | Positive and negative aspects of the experience with the ambulance services. | Peace of mind was emphasized. Peace of mind that they were receiving adequate advice, treatment, and care by the attending ambulance personnel. The professional behavior by the personnel provided peace of mind, the confidence they show in the care, communication, a short wait for receiving assistance, and continuity during transfers. |

| 2013 [9] | Denmark | Learning the perception that patients have about the entire “chain of survival” before arriving at the hospital, from the moment they dial 112 until they arrive at the hospital, as well as the impact that using different levels of urgency has on the patient’s overall impression. | Mail survey | 1419 (response rate, 58%) | General impression, care, treatment, information, confidence, response time. | In general, 98% of patients who called 112 defined the pre-hospital care as either “very good” (82%) or “good” (16%). The overall impression was more positive in cases when patients had been informed about the expected response time and when the evaluation of the degree of urgency by the SEM coincided with the patient’s self-evaluation. The level of urgency perceived by the patients was often lower than that evaluated by the SEM. The highest scores were observed in relation to how the ambulance was driven (91%), the confidence in how the ambulance personnel (including pre-hospital nurses and physicians) handled the situation (91%), and the respect by the personnel (90%). The lowest scores were related to the apparent preparation of hospital personnel upon patient arrival (72%), sufficiently rapid ambulance arrival (74%), and sufficient involvement by family members (77%). The specific aspects that had a high relationship with the patient’s overall impression and obtained low scores were the following: care provided by calling 112 [79.1 (75.8–82.4)], ability of the ambulance personnel to explain to them what was being done to them [79.3 (77.1–81.6)], and involvement by family members in accordance to the needs of the patient [76.9 (74.0–79.7)]. |

| 2013 [21] | Sweden | Describe the experiences of elderly patients who have used pre-hospital emergency services after a fall due to a suspected hip fracture. | Interview in patient’s homes | 10 elderly patients | Experience with the ambulance service. | 3 themes emerge: efficiency (the service was efficient, structured, and rational); that relative to the meeting (in the relationship that is established, during the meeting, between the personnel and patient the elements highlighted most are the dialog and tact, as well as the combination of empathy and medical knowledge); and suffering (they feel they are excluded from the decisions and confused by the drugs to relieve pain). |

| 2013 [22] | Germany | Investigate the effects of the sociodemographic factors of the patient or his/her relatives with the satisfaction with the care of the pre-hospital emergency services. | Paper and online questionnaire | 57 immigrant users and 161 nonimmigrant users | First part: sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education level, birthplace of patients, and their nationality). Second part: factors related to incidents occurring during the emergency services (sensations, emotions during the care provided by the emergency service). The third part analyzed factors related with the service and the experience with the emergency service. Its last section analyzed the overall satisfaction with the pre-hospital emergency service. | Most aspects related to satisfaction are explained by aspects related to the service rather than by sociodemographic aspects. The fact of being an immigrant does not show a significant relationship whereas the fact of having better or worse German language skills was related negatively with satisfaction. Professional, social, and emotional competencies were related significantly with the satisfaction of hospital pre-emergency services. (See annex: questions asked) |

| 2012 [23] | Australia | Analyze what factors of patients were determinant in the paramedics for not taking them to the hospital. | Semi-structured telephone interview | 20 patients | Experiences of the participants in the adopted decision, the factors that influenced such decision, and the consequences of not being transported to the hospital. | The reasons for not going to the hospital were varied (they only sought assistance, advice and/or support; the problem was resolved before the ambulance arrived; they did not want to go to the hospital for personal reasons, etc.). On most occasions, they did not remember the advice given to them by the paramedics or whether they had advised them about anything. All patients expressed high satisfaction with the ambulance service. |

| 2012 [10] | New Zealand | Determine the experience and opinions of patients in relation to the first extended care paramedic (ECP) before considering its implementation in other locales within the region. Determine if patients consider that the Urgent Community Assistance model is effective and acceptable, and whether there are differences in satisfaction with the care provided by groups of paramedics: standard service of urgent ambulance and extended assistance. | Face to face or telephone survey (depending upon the patient preference) | 100 (50 patients who had been attended to by the standard urgent ambulance service and 50 attended to by urgent community assistance) | Wait times (from placing the call until the ambulance arrives; from hospital arrival until care begins); time of dedication; treatment; satisfaction with evaluation at home; clarity of the information about treatment; preference on assistance location (home vs. hospital); information about what to do in case of deterioration; general satisfaction with care received; information about transport to hospital; comfort during transport (ambulance). | Patient satisfaction with the care received was very high regardless of the group of paramedics that cared for them, and the location wherein they were cared for (9.5–9.6/10 home; 9.8/10 hospital). 100% considered that the treatment received by paramedics was adequate. 77.8% preferred or would have preferred to be cared for in their home. 93.5% of patients who received healthcare in their home considered that they had been informed clearly about the treatment. 91.8% of patients who were transported felt comfortable in the ambulance and 96.2% received information on the reasons for the transport. |

| 2012 [24] | USA | Determine if a relationship exists between the perception of the quality of the care and satisfaction of patients who have used healthcare transport regarding treatment for pain experienced in pre-hospital settings. | Retrospective review of patient satisfaction data | 2741 patients | Patient satisfaction scale using a 5-point Likert scale (Excellent to Poor). Scale items: knowledge and abilities of EMS personnel, attentive and caring attitude, instructions, or explanations about the treatment or tests, explanations given about any medication and its secondary effects with respect to race and culture, and the availability of the technology necessary for treating the patient in situ. As for the quality of the care provided, they are asked with a direct item. | 65.9% indicated that the care received was excellent. Of the patients who indicated that the treatment for managing pain was excellent when using non-severe transport services, 79.0% affirmed that the overall quality of the care was excellent, while only 21.0% of those patients indicated that they had received excellent overall care when the treatment for pain management was not. When the patients indicated that the emergency medical personnel was excellent in terms of the assistance given for reducing pain and explaining the treatment, they were 2.7 (95% confidence interval: 1.4–5.4) times more likely to claim that the overall quality of the care was excellent. |

| 2012 [25] | United Kingdom | Describe experiences of patients with angina pectoris or infarction who have used ambulances. | Semi-structured interview | 22 patients | Experiences with 4 main issues: communication, professionalism, treatment of the problem, and transport from home to the hospital. | For patients, knowledge and relational skills contribute to the perception of professionalism. They emphasize professional-patient communication as a key element, and the experience is more positive when they feel that their physical, emotional, and social needs have been addressed. |

| 2011 [26] | Sweden | Evaluate patient satisfaction with the healthcare assistance received from the ambulance service by using the Consumer Emergency Care Satisfaction Scale (CECSS). | Scale of measurement of patient satisfaction with the nursing care in the emergency room | 40 patients from two different regions (20 from each one) | Measures patient satisfaction with the care, competence, and education. | The average time of assistance by ambulance was 31 min. 93.1% of the participants chose the most positive response option for each question on the scale. The item valued most was “The nursing personnel took time to attend to my needs.” On this, all participants marked the most positive option. |

| 2011 [27] | United Kingdom | Explores the acceptability of the lone telephone number for urgent care, NHS 111. | Mail survey to those who had called 111 | 1769 responded (41% response rate), of which 872 supplied comments (49% of those who responded) | Multidimensional satisfaction: aspects of patient-centered care (relief, assistance from personnel), access (clarity upon when to use the service), communication and information (importance of the questions posed), technical quality (whether they advised correctly), and efficiency (speed in solving their problem). | 75% indicated that the advice given had been very useful, and 28% said it was sufficiently useful. Most of those surveyed (86%) indicated that they fully complied with the advice. 63% were very satisfied, and 19% were sufficiently satisfied with the service in general. Users were less satisfied with the relevance of the questions asked and with the accuracy and relevance of the advice given than with other aspects of the service. Users who were referred to call NHS 111 were less satisfied than those who had called directly. |

| 2010 [28] | Portugal | Systematic review of evidence on the TTAS (Telephone Triage and Advice Services), the impact they have on the healthcare systems, and the methods and measures used in these studies. | Systematic review of the literature | 55 papers | The studies reviewed on satisfaction use Likert-type scales to evaluate the quality of this telephone service. | In the specific case of studies of TTAS satisfaction, there are high levels of satisfaction declared by patients; however, in the studies reviewed, satisfaction is less when the TTAS constitutes a barrier to traditional care (for example, home visits). |

| 2009 [29] | Sweden | Assess user perception of telephone helpline handled by nursing. | Qualitative research. Unstructured interviews | 12 service users | Accessibility, perception about how the user was treated, and about the quality of the recommendation. | Accessible and trustworthy operators. Respect, courtesy, response capacity, correct self-care recommendations in the opinion of the users assessed positively. |

| 2009 [30] | Spain | Describe the quality perceived by external users of a non-medical health transport unit. | Interviews were given within the hospital upon arrival or after returning home. | 317 external users of the non-medical health transport of Alicante | Satisfaction of external customers with the service received: if an ambulance was requested by telephone or personally, when it was requested, the time it took the ambulance to pick them up, help and assistance to enter and exit the ambulance, driver friendliness and manners, courtesy shown to companion(s), time in transport, picking up other external customers on the same route, comfort during the trajectory, incidents during the trajectory, interior and exterior cleanliness of the ambulance, driving, and safety. | For 92.7% of users, the wait times for transport were under an hour, while in 7.2% of cases, the customer waited between 1 and 2 h. Transport was provided for services of rehabilitation and external consultations. When asked if they would recommend this service, 60.9% said they would surely recommend it, while 39.1% said they might recommend it. 57.7% of users said that the telephone service received to ask for transport was very good. The personal attention received in this service was assessed as very good by 53.3% of users. 52.6% indicated that the help and assistance during the service were very good. The friendliness and manners shown was assessed as very good by 60.2%. Courtesy and treatment shown toward companion(s) was valued as very good by 42.2%. 12.6% indicated that the comfort during the transport was very good. 29.3% thought that the ambulance interior was very clean. The driving and safety during transport were considered very good by 13.2% of its users. |

| 2008 [31] | USA | Evaluate the effectiveness of a pediatric nursing telephone counseling program in terms of satisfaction with the service and access to care by the guardians/parents of the pediatric patients. | Quasi-experimental study with 2 samples before introducing the telephone counseling program through nursing, and then again 8 months after program implementation | Pre-sample with 14 subjects (parents and guardians of children). Post-sample with 20 subjects (parents and guardians of children) | Questionnaire to evaluate the satisfaction and results of the telephone counseling given over the telephone. 19-item questionnaire: 13 Likert-type scale items, 5 closed-answer questions, and one open question. | The results showed that the parents/guardians of the pediatric patients who formed part of the nursing telephone counseling program were more satisfied with the advice provided, according to the telephone call, and the fact of making them participate in the decision making. The year prior to the implementation of the telephone counseling program, the call reception center received 5850 phone calls, while subsequent to implementation of the telephone service, the number of calls rose to 6003. |

| 2008 [11] | Malaysia | Obtain a measure of the satisfaction of patients with the ambulance service at the Sains Malaysia University Hospital. | Interview given before arriving at the hospital | 87 patients who used the ambulance service | Vehicle (5 items), attitude (5 items), transport (5 items), professionalism (5 items), efficiency (3 items), and image (1 item). | The scores for all elements evaluated varied between 9.3 and 9.7 out of 10. |

| 2007 [12] | United Kingdom | Evaluate satisfaction with a new care service with paramedics for elderly persons with mild illnesses. | Experimental study. Mail questionnaire taken 28 days after calling 999 | 3018 patients over 60 years of age (n = 1549 interventions, persons who had been attended by this new paramedic counseling service, and n = 1469 control) | General satisfaction. | Patients included in the experimental group indicated to a larger extent to be “very satisfied” than those in the control group (85.5% vs. 73.8%, p < 0.001). |

| 2007 [13] | USA | Evaluate the quality of the medical emergency service (a paramedic service that establishes the type that the patient requires for transport to the hospital). | Mail survey to all those who had used the service from 2001 until 2004 | 851 patients who used this service | Courtesy, clarity of information, and overall satisfaction. | In the four years in which they were surveyed, 99.5% were satisfied. |

| 2007 [32] | United Kingdom | Analyze the perception of patients attended to in the emergency services. | Questionnaire on satisfaction with the emergency services | 43 users of the services | As a measure of the quality perceived in the patient questionnaire: wait time before being attended to, confidentiality and respect for rights, personalized attention, applied counseling, ability to listen and understand, delivery of informed consent. | Good performance translates into elevated patient satisfaction results. |

| 2007 [33] | United Kingdom | Evaluate the adequacy, satisfaction, and cost of the emergency professionals (ECP, Emergency Care Practitioner). Increase the understanding of the effect, if any, that emergency professionals have in offering healthcare services on a local level. Evaluate whether ECP efforts save costs. | 524 patients (245 experimental group (treated by ECP) and 279 in the control group (treated by the usual professional) | General satisfaction, future preference. | Three days after initial contact with the service, a greater number of patients from the ECP group than those from the control group affirmed to be “very satisfied” with the consultation (85.4%, n = 105 vs. 66.4%, n = 85). 77% (n = 100) of patients seen by the ECP said that in the future they would prefer to be treated by ECP professionals instead of any other type of healthcare professional. The emergency professionals provided more treatments (Chi2 = 26.0, p < 0.001, df = 1) and advice (Chi2 = 8.0, p < 0.001, df = 1). The ECP were more likely than the professionals from the control group to discharge patients at their very home instead of transporting them to the hospital, and of those who answered the follow-up questionnaire, it was more probable that the patients were very satisfied (Chi2 = 6.2, p < 0.001). | |

| 2006 [34] | United Kingdom | Compare the experience of patients who received care from emergency healthcare personnel (emergency care practitioners, ECP) with other patients who received care from traditional ambulance professionals (paramedics registered by the state or emergency medical technicians). | Mail questionnaire | 888 (response rate, 53.6%) | General satisfaction with the care: wait time, courtesy, attitude, listening, information, relevance of the treatment, adequacy of evaluation, comfort. | For most aspects related to the care, the majority of participants assigned “very” positive scores, although the frequency of these was less than 50% of that referring to “explanations about what would happen afterwards” (35.1–44.5%), “information provided” (38.0–44.8%), and “feel comfortable with what has happened” (40.6–45.1%). It was more likely that patients attended to by emergency healthcare personal, in comparison with those cared for by personnel of traditional ambulance services, to score “very” positively the “explanation by personnel about what would happen” (OR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.1–2.1) and the “thoroughness of the evaluation” (OR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.0–1.9) (although the difference in the latter was not maintained when controlling the variation in the transport). In short, the experiences of patients attended to by emergency personnel and those attended to by traditional ambulance services (paramedics or technicians) were similar and generally positive. However, in two areas, the care provided by emergency personnel was considered better. |

| 2005 [35] | Sweden | Determine how patients with acute chest pain experience the emergency call and their pre-hospital care. | Semi-structured interview (open questions) | 13 patients | How was your experience? | The patients express fear in that the telephone operator would not understand the seriousness of their problem. For patients who were alone, the ambulance wait was difficult and they were scared they would lose consciousness and that nobody would find them. Contact with the telephone operator was important for the patients, and the information that the ambulance was in route reassured them. Patients who had previously had an unsatisfying experience with a telephone operator hesitated at the time of making the call and took longer to complete it. For the patients, it was important that the treatment begin at home and continue along the way to the hospital and for the telephone operator to confirm that they would be attended to (“everything is going to be fine”). The patients said they felt safe upon hearing they would receive professional help and that the ambulance was well equipped. The secure feeling increased in cases in which the patient had the opportunity to remain in contact with the patient until the ambulance arrived. The patients stressed the importance of adequate information during the call (that the ambulance is on the way and the approximate wait time). Patients’ confidence increased when they were the center of attention, the treatment was individualized, and a highly qualified professional came to their home. |

| 2005 [36] | United Kingdom | Evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ECP care (a new professional figure from the emergency service who attends, filters, and diverts patient care in emergencies) in England on different telephone service routes. | Controlled observational survey. It measures satisfaction during one of the study phases with patient surveys. | 524 patients who answered the survey | They measure satisfaction on a Likert scale in accordance with the following items: personnel had manners, personnel were worried about me, personnel listened to me, personnel responded to my questions, personnel performed a thorough medical examination, medical treatment was excellent, satisfaction with the recommendations and advice given, and general satisfaction with the care received. | In each item, the results were better among those who were treated by this new professional profile. |

| 2005 [37] | United Kingdom | Assess the joint work between nurses and paramedics when attending to a medical emergency in the home, reducing the number of patients who must attend the hospital emergency services. To accomplish this, the experiences of both professionals and patients were explored. | Qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Paper surveys sent to patients of the pilot service (paramedic and nurse) and to the user who received the standard service (only paramedics). | 64 patients (27 from the pilot group and 37 from the standard group) 11 patients involved in Focus Groups | In the patient questionnaire, the main categories analyze: Reasons for calling an ambulance. Experience when the emergency service arrived and the treatment. Perception of the care received. Following the advice received. Among the group of professionals, the main categories analyzed (before and after implementing the pilot experience): Opinion about the introduction of the service. Expectations about the types of calls that the teams of nurses and paramedics must attend to. Possible benefits and drawbacks of the service. Skills and knowledge gained. Concerns. After implementation of the pilot experience: Number of calls taken, types, changes. Facilitators and inhibitors of the new service. Experience about the teamwork. Benefits and drawbacks of the new service. Skills and knowledge utilized. | Patients who received the pilot service were very enthusiastic about the opportunities of receiving care in their own home. It was also a positive experience for the professionals. They underwent greater job satisfaction and increased their skills and knowledge. |

| 2004 [38] | United Kingdom | Develop and evaluate protocols for ambulance personnel when attending to non-serious cases, providing advice on self-care and referring to other services without using health transport. | Experimental study. With a battery of items, they measure satisfaction of the users of the service. The scale is a 5-point Likert. | 251 in the experimental group and 537 in the control group | They measure satisfaction with a battery of items: The ambulance personnel listened attentively when I spoke about my problem, the people were friendly, the number of tips given by them were adequate, a sensation of calm after talking with the physicians, satisfaction with the explanations, clear advice about when I must request more help, general level of satisfaction with the service personnel, they made us feel like we were wasting the physicians’ time. | A greater portion of the patients in the experimental group declared themselves satisfied. |

| 2003 [39] | USA | Evaluate the quality and cost of the telephone service based on a triage system by nursing. | In-person survey or a telephone survey (as per patient preference). | 300 tutors of pediatric patients aged 0 to 16 years who utilized the Computerized Telephone Nurse Triage system (CTNT). | SERVQUAL Questionnaire administered via the telephone. This contains 16 items grouped into 4 dimensions on a 7-point Likert scale. This questionnaire measures quality of the services based on perceptions: Sociodemographic variables: gender, relationship with child, age, education, type of employment, number of times call center has been utilized, age of child, gender of child, date of birth, number of children in the family. | The average SERVQUAL score was 6.42. For the confidence dimension, the score was 6, it was 6.71 for the sensitivity dimension, assurance of quality scored 6.47, and the empathy dimension was 6.65. Most users who called: working mothers assessed the quality of service highly. Neither the education, level of employment, age of the user, gender of the child, year of birth, whether the children were twins, nor the age of the children affected the quality of the service when evaluating. Parents (male) of children assessed the quality of the service at a lower level. The method of telephone triage is well accepted as an alternative to providing healthcare that can be useful for many parents of children. |

| 2003 [14] | Australia | Analyze the levels of satisfaction with ambulance services in the Australian state of Victoria. | Questionnaire | Cannot be determined | Those surveyed are more satisfied with the ambulance services than with the emergency services. | |

| 2002 [40] | United Kingdom | Analyze the acceptability of a telephone assistance system for emergencies (Emergency Medical Dispatch). | Mail surveys sent to two randomly selected samples of 500 users who had called 999 beforehand, and one year after implementing the EMD service. | 355 users from before the EMD system was implemented answered the system (72% response rate), along with 297 users one year after implementation (63%) | Speed by which the telephone was answered, number of questions asked, importance of the formulated questions, returning the call when necessary, satisfaction with the telephone call, whether advice was given, advice was not given but was necessary, satisfaction with the quantity of tips, use of the tip (if given). | There was a decrease in users who considered that all questions asked were relevant (81% vs. 70%), which did not affect the percentage of users who were very satisfied with the call to 999, which moved from 78 to 86%. Satisfaction levels with the quantity of counseling increased (35% vs. 56%). The proportion of those surveyed who were very satisfied with the service in general increased from 71 to 79%. In the written comments, two problems were detected: some users were given advice to carry out actions that subsequently proved to be unnecessary; and second, a small number of persons who called felt that the ambulance crew did not treat the situation as seriously as they would have liked. |

| 2002 [15] | USA | Analyze the effect of an educational program for ambulance medical professionals and a quality improvement cycle, which helps physicians decide upon the need for transporting patients over 65 years of age in an ambulance who have not been transported. | Pre- and post-observational study. Telephone interviews with patients over 65 years of age who had contact with the ambulance physician but were ultimately not transported. | 151 patients in the first phase and 109 patients in the second phase | One direct item that measures satisfaction. | In the first phase, 94.7% declared themselves satisfied. In the second phase, 100% declared themselves satisfied (OR = 0.08; p = 0.03). |

| 2000 [41] | United Kingdom | Analyze the usefulness of the new service, NHS Direct, 24 h of telephone assistance with nursing personnel, which was implemented to “provide information easier and faster for persons about health, illness, and the NHS so they become more capable of caring for themselves and their family members.” | Mail questionnaire sent to those who had called during a specific week of September 1998, which was sent a week after their call and, and subsequently two reminders. | 719 answered (71%), of which 579 left written comments (81%) | Usefulness of the nursing advice, the reason why the service was useful (peace of mind, help in contacting the correct service, learning to address problems on their own, avoiding contacting a service, learning to avoid future problems, carried out the advice (yes, completely; yes, some; no). | Most answered that the nursing advice was very or sufficiently useful (643; 95%); many carried out the advice given (566; 85%). The most common reason they found the advice useful was that it gave them peace of mind (425; 66%). |

| Professionals | Caller/User | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accessibility | |||

| 1.1 Telephone (061/112 service) | |||

| Confusion about the services offered by 061/112 “Some still keep referencing the former ‘Sanitat Respon,’ they think they are calling 112;” “People are very confused;” “People today, because of all the TV ads for 112, think that 112 is for everything. Even when the primary care centers have to provide information, they say to call 112, and the chain starts from there…” | 13 | Health and administrative consultations recognize 061 as a support service. 112 is mostly for emergency consultations “The last time I called, almost a year ago, I was having a heart attack. My brother was with me and I said we’re going to call because I had very strong chest pains, and they came right away.” | 8 |

| 1.2 Ignorance about alternatives to dialing 061/112 | |||

| Use of other alternatives (chat/email) to a lesser extent by users | |||

| “The main criticism of users, and why they use other channels, is the cost of the call. Users are asking you about urgent things by chat. My water just broke, I’m having contractions, or my daughter is choking, by chat…” “And emails to avoid paying for the service.” | 11 | “I made the consultation by email.” “I know about the mobile app, but I prefer to use the telephone.” “I didn’t know there were other ways to contact them.” “Email is slower than calling, because when calling, they respond right away.” | 6 |

| 1.3 Types of consultations made | |||

| Administrative and health consultations “Fever, consultations about fever;” “Anxiety … suicidal thoughts. ”“They would tell you about vaccinations, they would give you information related to the trip…;” “The type of health consultations is not for urgent things, but rather about fevers, vaccinations.” “Information about their health card.” | 11 | Greater demand for health consultations“ The telephone must be used for health emergencies.” “I called because I needed to make a consultation outside of my primary care center’s operating hours.” “It is an alternative to visiting your primary care center.” | 11 |

| 1.4 User/Caller/Affected individual as persons who initiate the support service | |||

| Greater difficulty for resolving the problem when the caller is not the affected person“ A lot of people call who are not those affected.” “Many times the wife calls us, the wife of a 40–50 year-old who is right next to her, then she begins asking him questions, and you end up asking if she can just give him the phone.” | 15 | The caller does not realize that the assistance can be complicated when making contact with the affected person is not possible“ It wasn’t me who called; it was a family member who did.” “The last time I called, almost a year ago, I was having a heart attack. My brother was with me and I said we’re going to call because I had very strong chest pains, and they came right away.” | 3 |

| Professionals | Caller/User | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Call answered and classified | |||

| 2.1 First initial contact with the telephone operator | |||

| Rapid initial response if the call is made to 061 or 112 | |||

| “There are problems; a call reaches us after the patient had activated their medical alert button…” “Elderly people push the button, they talk to the medical alert people, and medical alert has neither resources nor physicians nor anything, so they transfer the call. Many times elderly callers are not aware that they are speaking with 061.” | 3 | “They are very fast;”“I didn’t have to wait;” “They are relatively fast.” “They answered the telephone quickly.” “I waited between 3 and 5 min.” | 5 |

| 2.2 Phone transfer to health professional | |||

| The phone transfer from the telephone operator to the specialist is perceived as the moment when a delay in care occurs | |||

| “The user calls and the telephone operator classifies the call, and tells the user that they will call him back as soon as possible.” [When there are other emergencies]. “You have to follow an algorithm because you have to guarantee that the information reaches the channels, then the protocol, sometimes depends upon whether the operator is new … It does not stop being a superficial tool as sometimes it turns out that if it is a hemorrhage, an ambulance is sent due to protocol, but just the same, a grandfather is calling you because he’s been having a slight nose bleed for all of three minutes. Then sometimes things are activated outside of protocol … an ambulance is sent and then, of course, I’m calling because my gums are bleeding.” “Of course, it’s different; it’s because of the priority. It’s not the same, a priority 0 enter the queue, and it’s different.” “The wait is between the telephone operator and the health professional, and there it can be 10 min.” | 18 | “I think they could have made me wait less time considering that it’s not a free phone call.” “They assist you quickly over the phone, but there is some delay in transferring you to the health professional;” “It depends upon the day, sometimes they don’t take long while other times they are slow;” “I had to wait a long time before they responded.” “A receptionist helps you first, taking your information, and then transfers you to a doctor or nurse.” “After talking to the first person, they transferred me directly to the health professional.” | 8 |

| 2.3 Repetition of the same information to different professionals | |||

| Request for the same information from the caller/user by different professionals “He takes some information and transfers the call;” “This makes the interrogation very difficult because the caller is already annoyed.” “By time the physician arrives, the patient has repeated the same thing 3 times.” “People complain that they repeat everything many times, that you always ask the same questions;” “This is already the fourth or fifth time!” “I have to say the same thing again?” | 5 | User/Caller assesses the questions asked as necessary concerns “They asked me the questions necessary for resolving my problem.” “They were very concise with the information they asked me about.” “The questions they ask are those necessary for learning what is happening to me.” | 7 |

| 2.4 Identification of the professional and his/her role | |||

| Role of the professional is not identified or assessed by the user/caller | |||

| “Sometimes they don’t listen, you know? I introduce myself as a nurse, but… ”“When the person attending is a nurse, it is sometimes necessary to make the user understand the nurse is completely capable of fulfilling her role.” “Many believe that a physician should take care of them.” | 8 | “I don’t recall them telling me what type of professional he was.” “I think the person who resolved the consultation was a doctor.” “A doctor and a nurse took care of me.” “The person who responds to your consultation is identified by the type of profession, but not by name.” | 11 |

| 3. Assessment of the care provided over the telephone | |||

| 3.1 Professionalism of the personnel who answered the telephone | |||

| The perception that professionalism increases the level of confidence in the user/caller | |||

| “And tell them we are going to help them.” “Speak with him and calm him down.” “Don’t be hesitant; I think he senses that it’s clear to you.” “I believe that what they want, depending upon the type of consultation, is to know what they can find and how they have to act. The uncertainty about how it might go for them causes some anxiety that you can lower if you give them that information.” | 15 | “I had the feeling that the person who treated me was a good professional.” “You can tell that they know about and control the information that you need.” “It seemed to me that the professional knew what she was doing.” | 6 |

| 3.2 Comprehension of the information provided by the caller/user | |||

| Elements that make the user/caller perceive that his/her demand is understood | |||

| “I repeat back what she has told me.” “The funny thing is that some times, if you listen until the very end, you do not resolve anything, but they literally say thank you for listening to me.” “Speak at the patient’s level.” | 8 | “I felt like I was understood.” “He asked me the necessary questions to understand what I needed.” “Most times they understand you, but it also depends upon the problem.” | 7 |

| 3.3 Kindness and empathy toward the user/caller | |||

| Sensation of kindness and capability of handling the emotions of the user/caller | |||

| “But they call right away to ask for assistance, and then you reassure them?” “Try to empathize with the patients. I understand that it is like this…” | 5 | “The professional who helped me was very kind.” “She treated me very well.” “They showed an interest in what was happening to me and were very kind to me.” | 6 |

| 3.4 Clarity of the information | |||

| Perception that the professionals provide clear information | |||

| “The information provided by the professional must be clear.” “Attempt to provide answers to the consultation.” | 3 | “The information provided by the professional was clear.” “He did not adapt the information to my level and so it was very difficult for me to understand what he was talking about.” | 2 |

| 3.5 Resolution of the problem | |||

| Resolving the problem that they have called about is essential for assessing the quality of the service | |||

| “The most important thing for assessing the quality of the call is to resolve the problem they called about.” “The emergency service resolved the problem for me.” “Try to provide answers the consultation.” | 3 | “They resolved the problem I called about.” “They did not answer my consultation.” “They told me I would receive the individual health card (TSI) within two weeks, but months passed.” “The resolved my consultation;” “Most of the times that I have called, they gave me the answer that I needed.” | 7 |

| Professionals | Caller/User | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4. Mobilization of the resource | |||

| 4.1. Arrival time of the healthcare resource | |||

| Arrival time in urban areas between 5 and 10 min after receiving of the call | |||

| “If it is within the coverage area, between 5 and 8 min.” | 5 | “The truth is that whenever I have called, they have taken 15 min at the most.” “061 gets there right away.” | 9 |

| 4.2. Telephone accompaniment until the professional assistance arrives | |||

| In most cases, there is no telephone accompaniment except for very specific situations | |||

| “Maintaining contact with the caller to guide the ambulance is not common because in some cases it may take half an hour.” “If the caller is on a ledge and tells you he is going to jump, you send the assistance but keep speaking with him.” | 2 | “They did not remain on the line until the ambulance arrived.” “As I was by myself, they told me to open the door, and they remained with me until the ambulance arrived.” “In some serious situations, it is necessary for the professional to remain on the line.” | 5 |

| 5. Arrival of the assistance and care provided in situ | |||

| 5.1. Assisting team | |||

| Difficulty of the caller in identifying the professional profile of the assisting personnel | |||

| “The caller does not identify between technicians and physicians.” | 3 | “I thought two nurses were coming.” “I don’t know what to say. There were two persons looking after me the whole time.” | 8 |

| 5.2. Care received | |||

| Special attention in transmitting confidence in the decisions made by the personnel | Care received that is perceived as correct and complete | ||

| “We say it confidently and explain why.” “They need to see us calm, and not act like chickens with their heads cut off.” | 3 | “The look at my oxygen levels, everything.” “They did several tests; they drew blood, and took my blood pressure.” | 6 |

| 5.3. Information | |||

| Explanations given to the user or family on care given and decisions made | |||

| “We try to explain to the user everything that we do to him.” “How she is, what she has, where we are taking her, what is the diagnosis.” “What we are doing and why.” | 3 | “They tell my family everything they do to me.” | 1 |

| 6. Decisions about the transport | |||

| 6.1. Choice of health center | |||

| In most cases, the professionals and the user negotiate the destination center | |||

| “We must negotiate more in the basic assisted transport than in the advanced ambulances because it depends upon the area.” “Here in Barcelona, we negotiate a fair amount, a lot … we almost always end up doing what the user demands even though it might not be the most suitable site.” | 5 | “They decided to take me to the hospital that does everything to me.” “They asked me what I thought about them taking me to my hospital and I said that was fine because it was closest to where I lived.” “I already told them to take me to my hospital.” | 8 |

| 6.2. Notifying family members of the user about the transport | |||

| Despite the inexistence of a protocol about notifying family members, in the cases in which the user requests such notification, it is attempted | Preference of the user him/herself to notify family members | ||

| “At some point, for humanity’s sake, you can notify family members if the user is elderly and unable to call.” “Sometimes they ask you, ‘Can you please call my daughter?’” “For humanity’s sake, not due to some protocol.” | 4 | “I wanted to notify my family so that they wouldn’t get any more alarmed than necessary.” “The team of professionals did not notify my family because I refused.” “I kept my family informed with my cell phone.” | 3 |

| 7. Care during transport | |||

| 7.1. Safety during transport | |||

| Safety mechanisms and protocols during vehicular transport for both users and professionals | 2 | Perception that the vehicle moves quickly but does so safely | 1 |

| “The little girl went with her harness and the nurse rode in the cab because everybody has to be seated.” “Safety is paramount. No professional may travel standing up.” | “They go fast but do so normally and safely.” | ||

| 7.2. Accompaniment by family members during transport | |||

| Possibility for the user to be accompanied by a family member within the cabin with exceptions for pediatric cases | |||

| “As a driver, you try to provide support for the family member who rides beside you during the transport. You try to redirect and control the situation so that when they reach the hospital, they feel a bit better.” “The mother or father always rides in the back with the child if the child is relatively stable. If we anticipate that the condition may worsen, then the family members ride up front.” “In a critical situation, the parent rides up front in the cab.” | 2 | “My family member rode up front.” “My mother also went along with me, in the part with the driver.” | 3 |

| 7.3. Safekeeping of personal belongings | |||

| Despite the inexistence of a protocol for collecting and safeguarding a user’s personal belongings when found in a public location, the personnel offer to take such belongings with them to the center of destination. | On some occasions, the personnel at the receiving center offer to safeguard a user’s personal belongings whereas on others, the user decides to take them with him/herself | ||

| “We try to give the user’s belongings to the police, but many times, they do not want them.” “Part of the report that we deliver in the hospital includes the user’s belongings. If they are valuable, they are turned over to a user’s family member, and the hospital is notified.” | 2 | “If you are in the ER and lucky, a professional appears, they safeguard your belongings.” “As I had my backpack with me, wherever the stretcher goes, so goes the backpack. I prefer not to leave my things in the hands of others.” | 2 |

| 8. Arrival at the health center | |||

| 8.1. Reception by the personnel at the receiving center | |||

| Triage is the moment in which the emergency healthcare transport personnel transfer responsibility for the user to the personnel at the receiving center | |||

| “Upon arrival at the center, triage is performed; at that moment, the user realizes that he is being taken care of by hospital personnel, and we move him from the stretcher to a hospital bed. It is at that moment that we disappear.” “The transport personnel inform the center personnel that they are passing the user to them, and at that moment, we leave the user in their care. When the user is removed from the stretcher, the activity by the transport personnel ceases.” | 2 | “Upon arrival at the center, we wait in the ER, they take you to triage, and you wait until your turn.” | 1 |

| Perception that an effective transfer of information is not always accomplished by the transport personnel to the personnel at the receiving center | |||

| “Hospital is completely full; they do not find anyone to leave me with, so many times, the transfer of information remains in the air.” “The transport personnel should insist a little bit in finding a doctor, because they leave you there with the information that you gave them.” “It depends upon the occasion. Sometimes, they leave you there with a long wait.” | 3 | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Alfranca, F.; Puig, A.; Galup, C.; Aguado, H.; Cerdá, I.; Guilabert, M.; Pérez-Jover, V.; Carrillo, I.; Mira, J.J. Patient Satisfaction with Pre-Hospital Emergency Services. A Qualitative Study Comparing Professionals’ and Patients’ Views. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020233

García-Alfranca F, Puig A, Galup C, Aguado H, Cerdá I, Guilabert M, Pérez-Jover V, Carrillo I, Mira JJ. Patient Satisfaction with Pre-Hospital Emergency Services. A Qualitative Study Comparing Professionals’ and Patients’ Views. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(2):233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020233

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Alfranca, Fernando, Anna Puig, Carles Galup, Hortensia Aguado, Ismael Cerdá, Mercedes Guilabert, Virtudes Pérez-Jover, Irene Carrillo, and José Joaquín Mira. 2018. "Patient Satisfaction with Pre-Hospital Emergency Services. A Qualitative Study Comparing Professionals’ and Patients’ Views" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 2: 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020233