In-Cabin Air Quality during Driving and Engine Idling in Air-Conditioned Private Vehicles in Hong Kong

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vehicle Recruitment and In-Cabin Air Measurements

2.2. IAQ Measurements

2.3. Questionnaires

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Questionnaire Result

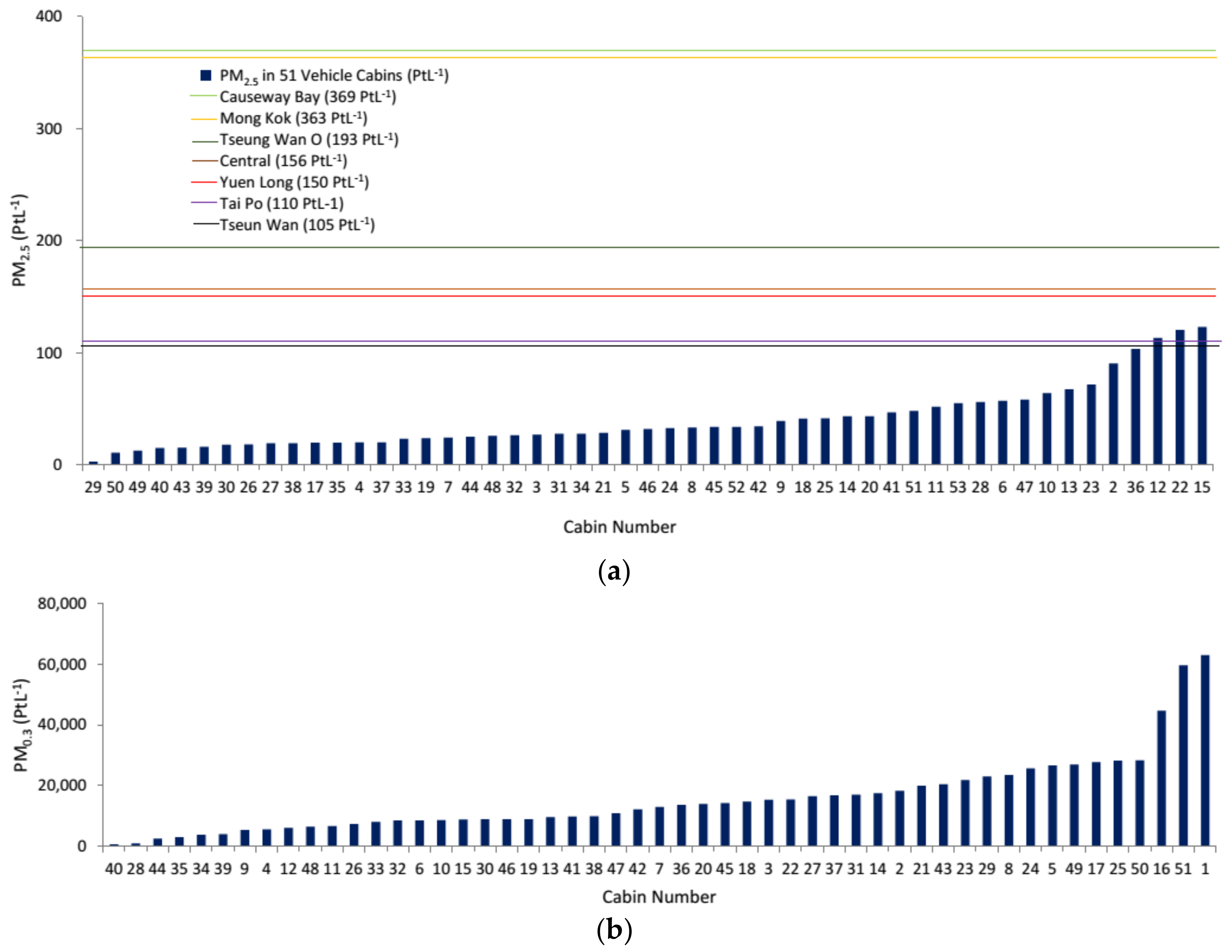

3.2. PM2.5 and PM0.3

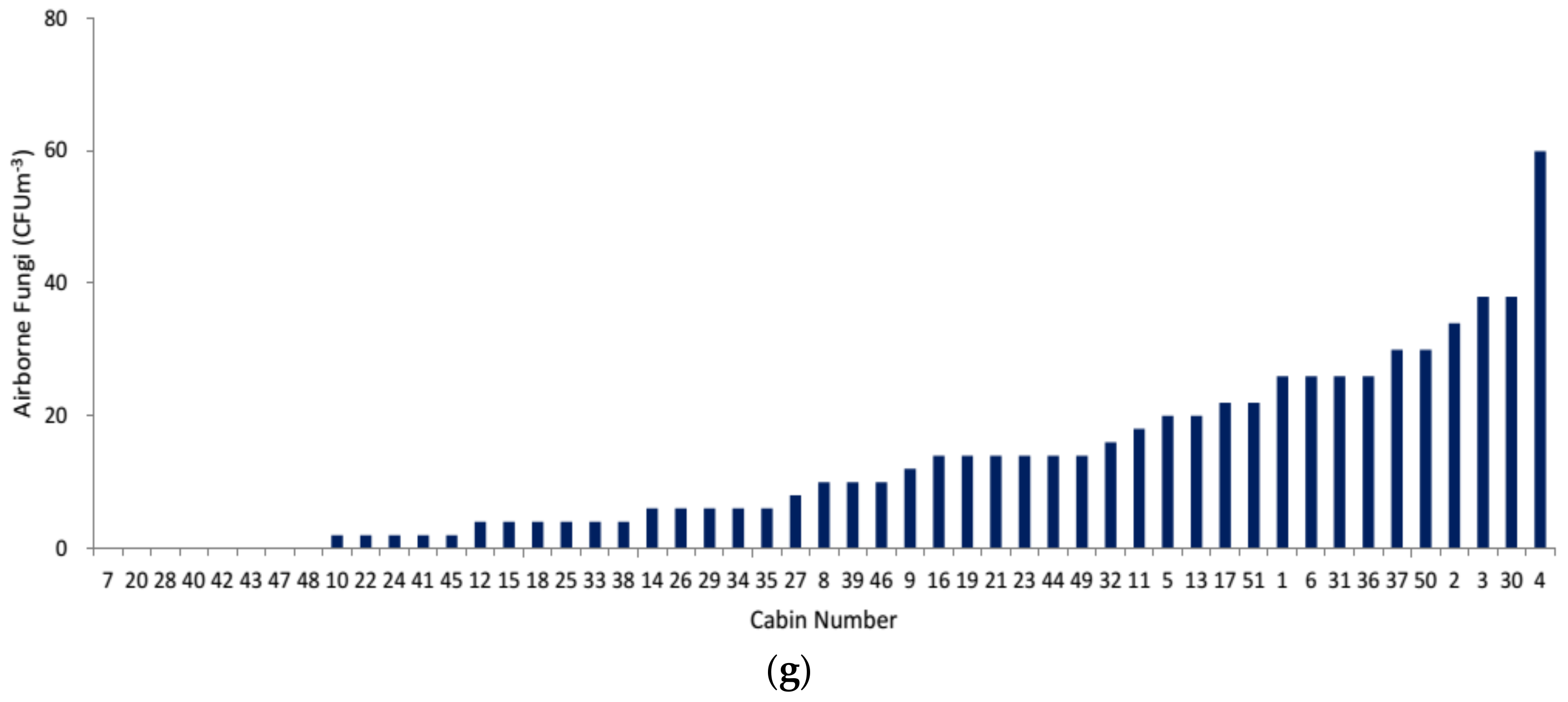

3.3. CO

3.4. CO2

3.5. TVOCs

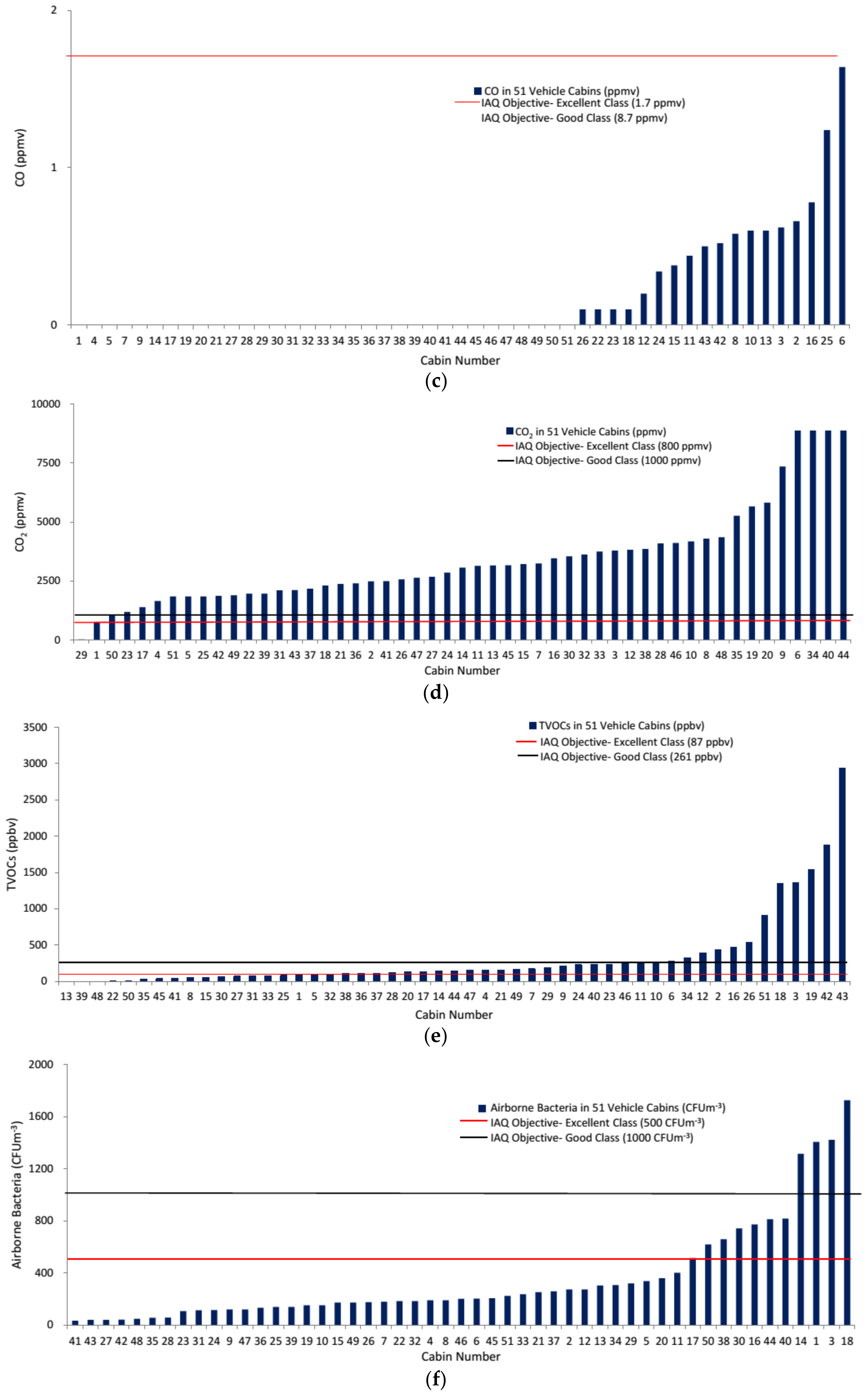

3.6. Microbial Counts

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts of High CO2 Concentrations on Air Quality, Comfort, Health and Road-Safety

4.2. Idling Engine: Everyone Pays

4.3. Improving In-Cabin Air Quality

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Müller, D.; Klingelhöfer, D.; Uibel, S.; Groneberg, D.A. Car indoor air pollution-analysis of potential sources. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2011, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, P.L.; Harrison, R.M. Roadside and in-vehicle concentrations of monoaromatic hydrocarbons. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Eiguren-Fernandez, A.; Hinds, W.C.; Miguel, A.H. In-cabin commuter exposure to ultrafine particles on Los Angeles freeways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 2138–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiss, O.; Tirendi, S.; Barrero-Moreno, J.; Kotzias, D. Investigation of volatile organic compounds and phthalates present in the cabin air of used private cars. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudda, N.; Kostenidou, E.; Sioutas, C.; Delfino, R.J.; Fruin, S.A. Vehicle and driving characteristics that influence in-cabin particle number concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8691–8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knibbs, L.D.; Cole-Hunter, T.; Morawska, L. A review of commuter exposure to ultrafine particles and its health effects. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 2611–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bigazzi, A.Y.; Figliozzi, M.A. Impacts of freeway traffic conditions on in-vehicle exposure to ultrafine particulate matter. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 60, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Matsunaga, I.; Tomioka, K.; Kumagai, S. Interior air pollution in automotive cabins by volatile organic compounds diffusing from interior materials: I. Survey of 101 types of Japanese domestically produced cars for private use. Indoor Built Environ. 2006, 15, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiss, O.; Barrero-Moreno, J.; Kotzias, D. Measurements of volatile organic compounds in car showrooms in the province of Varese (Northern Italy). Indoor Air 2011, 21, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Wu, Y.; Gong, Y.; Wu, S.; Wu, X.; Zhu, S.; Liu, T. Investigation of volatile organic compounds exposure inside vehicle cabins in China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2016, 7, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riediker, M.; Devlin, R.B.; Griggs, T.R.; Herbst, M.C.; Bromberg, P.A.; Williams, R.W.; Cascio, W.E. Cardiovascular effects in patrol officers are associated with fine particulate matter from brake wear and engine emissions. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2004, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Riediker, M. Cardiovascular effects of fine particulate matter components in highway patrol officers. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007, 19, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra-Vargas, M.P.; Guzman-Grenfell, A.M.; Blanco-Jimenez, S.; Sepulveda-Sanchez, J.D.; Bernabe-Cabanillas, R.M.; Cardenas-Gonzalez, B.; Ceballose, G.; Hicks, J.J. Airborne particulate matter PM2.5 from Mexico City affects the generation of reactive oxygen species by blood neutrophils from asthmatics: An in vitro approach. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2009, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.Y.; Lau, W.L.; Lee, S.C.; Chan, C.Y. Commuter exposure to particulate matter in public transportation modes in Hong Kong. Atmos. Environ. 2002, 36, 3363–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.Y.; Lau, W.L.; Wang, X.M.; Tang, J.H. Preliminary measurements of aromatic VOCs in public transportation modes in Guangzhou, China. Environ. Int. 2003, 29, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.Y.; Lau, W.L.; Zou, S.C.; Cao, Z.X.; Lai, S.C. Exposure level of carbon monoxide and respirable suspended particulate in public transportation modes while commuting in urban area of Guangzhou, China. Atmos. Environ. 2003, 36, 5831–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.; Chan, L. Commuter exposure to aromatic VOCs in public transportation modes in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 308, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yan, M.; Liu, J. Comprehensive evaluation of the air quality of public transport in Beijing. Environ. Health 2008, 25, 514–516. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X.; Tian, H.L.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, B.J.; Xia, X.Q.; Zhang, J. Investigation and analysis of the air quality of subway line 1 in Zhengzhou. J. Prev. Med. Henan Prov. 2014, 25, 465–468. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.; Zheng, M.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, H.; Li, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhu, Y. Commuter exposure to particulate matter and particle-bound PAHs in three transportation modes in Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 204, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Indoor Air Quality Management Group. Guidance Noted for the Management of Indoor Air Quality in Offices and Public Places; The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Hong Kong, China, 2003.

- Indoor Air Quality Centre. Available online: http://www.iaqhk.com/control.htm (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- Environmental Protection Department, the Government of Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region. Available online: http://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/english/environmentinhk/air/prob_solutions/idling_prohibition.html (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- Jung, H. Modeling CO2 Concentrations in Vehicle Cabin; SAE Technical Paper (No. 2013-01-1497); SAE Technical: Troy, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration). Sampling and Analytical Methods: Carbon Dioxide in Workplace Atmospheres; Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- ACGIH (American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists). TLVs and BEIs; American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2011.

- Walsh, D. The Drowsy Driving Off Switch-A simple control in vehicles could potentially reduce the prevalence of drowsy driving and have a huge impact on the number of crashes and associated deaths. Synergist 2012, 23, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Satish, U.; Mendell, M.; Shekhar, K.; Hotchi, T.; Sullivan, D.; Streufert, S.; Fisk, W.J. Is CO2 an indoor pollutant? Direct effects of low-to-moderate CO2 concentrations on human decision-making performance. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1671–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, W.K.; Park, K.H. Concentrations of volatile organic compounds in the passenger side and the back seat of automobiles. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 1999, 9, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, W.K.; Yu, C.H. Public bus and taxicab drivers’ work-time exposure to aromatic volatile organic compounds. Environ. Res. 2001, 86, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedoruk, M.J.; Kerger, B.D. Measurement of volatile organic compounds inside automobiles. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2003, 13, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Yang, T.; Tan, J.; Li, L.; Ge, Y. Characterization of VOC emission from materials in vehicular environment at varied temperatures: Correlation development and validation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Chen, X.; Xiong, J. Air quality inside motor vehicles’ cabins: A review. Indoor Built Environ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.H.; Van Langenhove, H.; Chigbo, S.I.; Amare, A.N.; Demeestere, K.; Walgraeve, C. Exposure to volatile organic compounds: Comparison among different transportation modes. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 94, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisel, C.P. Automobile, Bus, and Rail Passenger Air Quality. In Air Quality in Airplane Cabins and Similar Enclosed Spaces. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Hocking, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 4H, pp. 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Schlink, U.; Rehwagen, M.; Damm, M.; Richter, M.; Borte, M.; Herbarth, O. Seasonal cycle of indoor-VOCs: Comparison of apartments and cities. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO: The World Health Report: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, T.; Sundell, J.; Bischof, W.; Bohgard, M.; Cherrie, J.W.; Clausen, P.A.; Dreborg, S.; Kildeso, J.; Kjærgaard, S.K.; Løvik, M.; et al. ‘EUROPART’. Airborne particles in the indoor environment. A European interdisciplinary review of scientific evidence on associations between exposure to particles in buildings and health effects. Indoor Air 2003, 13, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawryk, N.J.; Weisel, C.P. Concentrations of volatile organic compounds in the passenger compartments of automobiles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996, 30, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonberg, R.P.; Gastmeier, P.; Kenneweg, B.; Holdack-Janssen, H.; Sohr, D.; Chaberny, I.F. The microbiological quality of air improves when using air conditioning systems in cars. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buters, J.T.; Schober, W.; Gutermuth, J.; Jakob, T.; Aguilar-Pimentel, A.; Huss-Marp, J.; Traidl-Hoffman, C.; Mair, S.; Mayer, F.; Breuer, K.; et al. Toxicity of parked motor vehicle indoor air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 2622–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, K.W.; Ge, Y.S.; Bin, H.U.; Ning, Z.W.; Zhao, S.T.; Zhang, Y.N.; Peng, X.I.E. Measurement of in-vehicle volatile organic compounds under static conditions. J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 19, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IAQ Parameters | Unit | 8-h Average | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent class | Good class | ||

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | ppmv | <800 | <1000 |

| Carbon monoxide (CO) | ppmv | <1.7 | <8.7 |

| Total volatile organic compounds (TVOCs) | ppbv | <87 | <261 |

| Airborne bacteria | CFUm−3 | <500 | <1000 |

| Questions | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car age | 0–2 years 27.5% | 3–5 years 31.4% | 6–10 years 27.5% | 10–18 years 13.6% | |

| Car mileage | 0–30,000 km 31.4% | 30,000–60,000 km 19.6% | 60,000–90,000 km 25.5% | 90,000–120,000 km 19.6% | No response 3.9% |

| Car usage | 3–4 days per week 37.2% | 5–6 days per week 37.2% | 7 days per week 25.6% | ||

| Frequency of cleaning | Every 1–2 weeks 21.6% | Every 1–2 months 33.2% | Every 1–2 years 21.6% | Never/Rarely 13.8% | Irregular 9.8% |

| Filter maintenance | Every 6 months 3.7% | Every 10,000 km 3.9% | Twice yearly 9.8% | Never 72.6% | |

| Filter types | Don’t know 96.1% | Original 3.9% | |||

| Suspected agents that could contribute to in-cabin TVOCs | No 68.6% | Plastic toys 2.0% | Fragrance 17.6% | Alcohol gel 3.9% | Do not know 7.9% |

| Air conditioner usage | All year 64.7% | Summer only 31.4% | Irregular 3.9% | ||

| Ventilation mode | Fresh air 19.6% | Recirculation 72.5% | Irregular 7.9% | ||

| Perceived pollution level along the travel route | Low 21.6% | High 21.6% | Average 56.8% | ||

| Any odors in cabin | No 70.6% | Yes 29.4% | |||

| Smoking in cabin | No 94.1% | Yes 5.9% | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barnes, N.M.; Ng, T.W.; Ma, K.K.; Lai, K.M. In-Cabin Air Quality during Driving and Engine Idling in Air-Conditioned Private Vehicles in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040611

Barnes NM, Ng TW, Ma KK, Lai KM. In-Cabin Air Quality during Driving and Engine Idling in Air-Conditioned Private Vehicles in Hong Kong. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(4):611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040611

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarnes, Natasha Maria, Tsz Wai Ng, Kwok Keung Ma, and Ka Man Lai. 2018. "In-Cabin Air Quality during Driving and Engine Idling in Air-Conditioned Private Vehicles in Hong Kong" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 4: 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040611