Abstract

We aimed at developing and validating a scale on the beliefs and attitudes of mental health professionals towards services users’ rights in order to provide a valid evaluation instrument for training activities with heterogeneous mental health professional groups. Items were extracted from a review of previous instruments, as well as from several focus groups which have been conducted with different mental health stakeholders, including mental health service users. The preliminary scale consisted of 44 items and was administered to 480 mental health professionals. After eliminating non-discriminant and low weighting items, a final scale of 25 items was obtained. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses produced a four-factor solution consisting of the following four dimensions; system criticism/justifying beliefs, freedom/coercion, empowerment/paternalism, and tolerance/discrimination. The scale shows high concordance with our theoretical model as well as adequate parameters of explained variance, model fit, and internal reliability. Additional work is required to assess the cultural equivalence and psychometrics of this tool in other settings and populations, including health students.

1. Introduction

The mental health sector has undergone two fundamental transformations in the last half century, namely Deinstitutionalization and Recovery [1]. Both processes have involved an increase in service users’ autonomy and freedom of choice. The Recovery movement has mostly been driven by service users themselves, which has entailed a significant increase in participation, and consequently a reduction in paternalistic behaviours carried out by professionals. These processes have also improved the professionals’ awareness of service users rights, and have led to a reduction of coercive measures and a shift from symptom reduction to rehabilitative and recovery approaches [2].

Despite all these improvements, many service users still report stigmatizing attitudes, including professional paternalism and emotional estrangement [3,4]. Therefore, receiving a mental health diagnosis is still considered as a predisposing factor that can lead to the experience of stigma from both the social environment [5] and mental health professionals [6].

Stereotypes depicting mental health service users as incompetent, weak, incurable, and violent lead to social discrimination and coercive professional practices [7]. Some examples are involuntary inpatient and outpatient treatments, forced medication, overmedication, electroconvulsive therapy under duress, mechanical restraints, seclusion, isolation, and arbitrary legal incapacitations and guardianships. The underlying beliefs that influence the decisions that professionals make appear to be formed by a lack of awareness of one’s own prejudices [4]. In this sense, the perception by some professionals that the moral side of their decisions is not relevant to the recovery process may contribute to the acceptance of coercion as a standard practice [8].

Given the extent of the consequences of stigma and coercion towards mental health service users, it is essential to raise awareness among mental health professionals in order to foster non-stigmatizing and empowering attitudes through frameworks such as Recovery [9] and Citizenship [10]. In the context of planning and implementation of these training and awareness activities, there is a need to evaluate the impact this has on the beliefs and attitudes of professionals through standardised measures.

Previous Measures

The first scale that included beliefs and attitudes among mental health professionals towards mental health service users was developed by Gilbert and Levinson [11]. This scale was used as a method to understand mental health practices on a continuum from custodial to humanistic [12]. Another scale dealing with professionals opinions about mental illness was validated shortly afterwards [13]. Alongside these early developments, Goffman re-defined the word “stigma” to refer to a non-physical, invisible signal, making a person’s social status undesirable [14]. Relatedly, different mental health stigma measures have been developed and are usually applied to the general public [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], mental health service users [23], and some others to professional audiences [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Another issue that has also generated assessment tools is the stigma perceived by those in the medical profession in general towards psychiatry in particular [30].

Over the last decades, in parallel to the rise of the Rehabilitation and Recovery movements, professionals have become more conscious of the need to offer a non-discriminant care based on users’ rights. In this context, measures on recovery-based knowledge [31,32,33], attitudes [34], expectations [35], and practices [36,37,38,39,40,41,42] have been developed (see Table 1). These instruments have enabled the evaluation of dozens of projects which have implemented the philosophy of recovery in many health institutions. However, there are also limitations of these instruments, including the impossibility of administering the attitudes and knowledge measures at baseline with lay professionals, given that they assume a certain degree of knowledge of the principles of recovery. Furthermore, all current professional stigma instruments are designed for certain professional groups [24,25,26,29] or mental health conditions [27,28]. Finally, scales measuring recovery practices assume that some level of implementation of these practices has already been done.

Table 1.

Previous measures of mental health professionals’ beliefs and attitudes towards service users’ rights.

So far, there is a lack of multidimensional measures that can be used to assess training and awareness activities attended by different mental health professional groups with heterogeneous levels of knowledge and awareness of the importance of respecting service users’ rights. For this reason, the objective of this work is the development of a flexible instrument in order to measure the beliefs and attitudes related to service users’ rights among all types of mental health professionals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development

An initial set of 44 items was developed in Spanish by researchers with a lived experience of mental health problems. This set was reviewed by Catalan experts on stigma awareness and community mental health including board members of the Catalan Federation of First-Person Mental Health Organisations, where all the members have lived experience of mental health problems. Half of these items were derived from a systematic review of previous measures (see Table 1). We reviewed scales on stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs as well as recovery-based knowledge and practices. We found items related to three cognitive levels: attitudes, awareness and knowledge, and four thematic domains: empowerment/paternalism, recovery, stigma, and rights.

Additionally, we conducted 11 focus groups with mental health professionals, 7 focus groups with service users, and 1 focus group with relatives of service users. The first six groups carried with mental health professionals and those carried with service users and relatives were used for the adaptation to the current context of items based on the literature and the creation of a pool of 22 completely new items. In the last five groups carried with mental health professionals, the scale was presented at the beginning of the session, leaving time for participants to respond. During the discussion, professionals could comment on the content and contextualise how they had answered the items.

The order of the items was randomised before starting the administration of the scale. Regarding the anchor points of the scale, we chose a four-point Likert scale (I fully disagree, I disagree, I agree, I fully agree). This mode helps to minimise middle response bias, which is frequent in attitude research [43].

2.2. Sample and Procedure

The sample used for the psychometric validation of the Beliefs and Attitudes towards Mental Health Service Users’ Rights Scale (BAMHS) was comprised of a total of 480 Spanish-speaking mental health professionals. These professionals worked in a diverse range of settings, including inpatient care, outpatient care, rehabilitation, supported work, leisure and free time services, etc. Among these, there were psychologists (29%), mental health nurses (15%), social educators working in mental health settings (15%), psychiatrists (12%), mental health social workers (7%), occupational therapists (4%), and other allied professionals including primary care doctors and nurses and non-specialists working with mental health service users such as community health workers and administrative staff (15%). The average age was 40.13, ranging from 23 to 65 years of age. Approximately 77% of the sample were women.

Participants in the study were gathered from a pool of professionals who had participated in discussions, training sessions and awareness activities on mental health service user’s rights. The scale was designed to be used as a baseline and follow-up measure.

The study received ethical clearance from the University of Barcelona institutional review board (IRB00003099). All participants gave informed consent and the questionnaires were completed anonymously.

2.3. Analysis

Before analysing the data, we carried out a search for outliers by calculating the mean of all the responses for each participant. We excluded a total of seven questionnaires from the analysis as they were indicative of extreme values (most answers corresponding to one of the Likert scale anchor points).

We calculated frequencies, asymmetry, and kurtosis parameters, as well as item-total correlations for each item in order to decide upon their inclusion in exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFAs and CFAs, respectively), in addition to univariate and multivariate Item Response Theory (IRT) exploratory and confirmatory analyses. EFAs were combined with CFAs through the identification of stable and theoretically congruent dimensions appearing in consecutive principal components analyses, for which fit could be tested through structural equation modelling. In parallel, the discriminative capacity of each item was tested using uni- and multivariate IRT analyses. Through the analysis of item-total correlations, EFA, and CFA factor loading valences, items that indicated that they should be reversed were recoded, with higher scores indicating larger presence of negative attitudes or beliefs (see italicised items in Table S1). Finally, reliability was tested using Cronbach’s alpha. The psych [44], lavaan [45], ltm [46], and mirt [47] packages for the R software [48] were used to compute all the statistical analyses.

3. Results

Frequencies, asymmetry, and kurtosis parameters for each original item can be seen in Table S1. Due to their low discriminative capacity, we decided to remove items with an asymmetry and kurtosis greater than 1 or less than −1 (eight items) and/or 90% of the cases included in one of the two halves of the Likert scale (nine additional items). We then calculated item-total correlations as well as a unidimensional IRT unconstrained latent variable model with the remaining 27 items. An item on professional pessimism (9), was removed because of nil (r = −0.034) correlation with the rest of items and low discrimination parameter (−0.057). All the remaining items had discrimination parameters above 0.5 within a unidimensional IRT model.

Consecutive exploratory factor analyses using Varimax and Oblimin rotations as well as exploratory IRT models were conducted with the 26 remaining items, using the eigenvalue-higher-than-one criterion in CFA and forcing the structure to 2, 3, and 4 factors in CFA and exploratory IRT. This procedure was repeated, temporarily excluding items with low and distributed loadings and low multivariate discriminant parameters. Once we identified a coherent item group (those that tended to remain under the same dimension with high factorial weights and discriminant parameters in different CFA and IRT analyses), we calculated its unidimensionality through Cronbach’s alpha and confirmatory factorial analyses as well as the discrimination parameters of the items. Each group was subsequently removed from the total pool of items and the whole process was repeated with the remaining items, until we obtained a congruent model (19 items) formed by four dimensions.

The dimensions were named as follows: system criticism/justifying beliefs (items 3, 10, 15, 16, 44), freedom/coercion (items 4, 6, 23, 34), empowerment/paternalism (items 1, 8, 27, 28, 38, 40), and tolerance/discrimination (items 12, 24, 25, 30). The dimensionality of the core model was analysed through confirmatory factor analysis showing a good fit (see Table S2). Discrimination parameters within a multidimensional IRT (MIRT) were also satisfactory (0.80–2.62). Additional items were added one by one, based on theoretical coherence, factor loadings and discriminant parameters in all EFAs and confirmatory IRT models which were incorporated during the previous process (see Table S2). We again tested the EFA weights (Table 2), reliability (Table 3), and unidimensionality (Table S2) for the whole set of 25 items and for each dimension. We also tested the fit of the whole model having added only a specific item (see Table 3 and Table S2). All items added to each subscale (11, 13, 14, 33, 37, and 39) improved its internal reliability and the fit of the whole model considered as unidimensional, without substantially affecting the fit of the four-dimensional model. As it can be seen in Table S2, adding item 21 worsened all unidimensionality parameters. Additionally, we considered that it could be included as part of the tolerance/discrimination subscale. However, it did not improve the reliability of that subscale, nor any of the rest, and hence, it was removed.

Table 2.

Factorial weights and discrimination data of the final item pool.

Table 3.

Reliability of the core structure, total scale, and four final dimensions including additional items *.

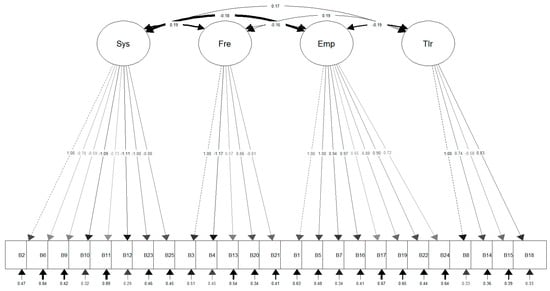

Figure 1 shows the CFA path diagram of the final model. Discrimination parameters within the final MIRT were also satisfactory (0.70–2.04, see Table 2). The final scale can be seen in Table 4 (original version in Spanish) and Table 5 (back-translated version in English).

Figure 1.

Structural equations diagram of the scale.

Table 4.

Spanish Version of the Beliefs and Attitudes towards Mental Health Service Users’ Rights Scale including scoring details.

Table 5.

English version of the Beliefs and Attitudes towards Mental Health Service Users’ Rights Scale including scoring details.

4. Discussion

According to our results, the BAMHS may be a useful tool to assess the impact of awareness and training activities on professionals’ beliefs and attitudes towards service users’ rights. This new scale offers flexibility and assumes no prior awareness or knowledge, making it especially suitable for its use in areas where user-led and progressive professional movements are carrying out activities with professionals without previous recovery knowledge or awareness of user rights violations.

The results illustrate four final dimensions, namely: system criticism/justifying beliefs, freedom/coercion, empowerment/paternalism and tolerance/discrimination. The scale can be scored conveniently in any direction, with higher scores signifying higher respect or a higher violation of rights. We simply advise potential users to make it clear in the methodology of their research report. The final structure of the BAMHS showed an adequate fit according to CFA parameters, good reliability, and good discrimination parameters. Adding six items to the core model did not substantively affect the overall fit of the model, nor that of each of the modified dimensions or the discrimination capacity of each of the items. Additionally, none of the items that were included worsened the reliability of each dimension or the whole model.

The first dimension of the BAMHS materialises the professional beliefs that health-related professionals have which justify the status quo. Claiming that mental disorders are diseases like any other, that their aggressiveness is due to their mental disorders, that it is not possible to recover without the intervention of a professional, and even that some patients will never recover are statements that reinforce the need for mental health staff and their interventions. Regarding the former topic, some authors have stressed the role of biological and genetic attributions in the process of stigmatisation, including the belief that most mental disorders are chronic conditions [54,55]. In some way, understanding that mental disorders are unrecoverable biological conditions might tip the moral balance towards the justification of coercion [56]. Accordingly, professionals scoring high on this subscale might also think that they only use these measures when necessary. In this context, declaring someone incapacitated might be considered an adequate way of care. Finding a justification for the use of extraordinary measures in the very nature of mental disorders might facilitate the concealment between the use of such measures and stating that “mental health service users now have the same rights as other people” and that “mental health professionals, in general, work collaboratively with patients”. These types of assertions are related to the complacency usually found among some mental health professionals despite the continuous use of coercion [57,58,59].

The freedom/coercion dimension addresses recurrent topics with mental health professionals when discussing service users’ rights. The subscale includes questions on involuntary hospitalization, mechanical restraints, and, inversely, respect for service users’ autonomy. We would like to highlight that more than half of our sample believed that mechanical restraints are sometimes necessary and that one should be involuntarily hospitalised even if they do not pose a threat to others. This is in contrast to the evidence that shows a worse prognosis [60], iatrogenesis [61,62], and even death [63] for people subjected to such coercive measures. Conversely, restraint reduction has been shown to be feasible [64] and to reduce the risk of injury and medical leave among nursing staff [65].

The next subscale, empowerment/paternalism, represents a series of beliefs related to the supposed inability of people diagnosed with mental disorders to take charge of their lives including having children, making decisions regarding their treatment, or prioritizing treatment over dignity [66,67]. This justifies paternalism in the form of guidelines and constant support, with emotionally distant and value-free practices [68].

Finally, the fourth subscale tolerance/discrimination materialises widespread prejudices towards mental health service users. Discrimination occurs in different contexts; for instance, this can include employment discrimination (as many would not feel comfortable with a diagnosed teacher) which is evidenced through low occupational rates [69]. Likewise, social distance reflects the main reason for the stigma that people with mental health problems experience [70,71]. Other discriminatory practices include access to healthcare [72], and those included in legislation, such as the prohibition to vote [73].

The main limitation of this validation study is the use of a convenience sample formed by professionals willing to participate in awareness activities. This may have caused biases, such as social desirability, due to the profile of the participants in the activities in which this validation is contextualised. However, this scale is designed to evaluate changes in professionals willing to participate in activities where patients’ rights are discussed. Therefore, we believe that it can be a useful tool to evaluate awareness activities in the mental health field. Future work should culturally and linguistically adapt the tool for other territories and establish psychometric properties.

We believe that the BAMHS, a relatively brief scale tested in diverse mental health provision contexts with a wide range of professionals, can be used to measure the impact of recovery and anti-stigma Targeted, Local, Credible, Continuous Contact (TLC3) methodology-based interventions [74] carried with mental health professionals.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we believe that our instrument brings a new perspective to the measurement of beliefs and attitudes of mental health professionals in the context of the new era opened by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [75].

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/2/244/s1. Table S1, Descriptive data of the initial 44 item pool; Table S2, Evolution of confirmatory factor analysis fit and discrimination parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.E.O.; methodology, F.J.E.O.; software, F.J.E.O.; validation, F.J.E.O.; formal analysis, F.J.E.O.; investigation, F.J.E.O.; resources, F.J.E.O.; data curation, L.L.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.-B. and F.J.E.O.; writing—review and editing, F.J.E.O.; supervision, F.J.E.O.; project administration, F.J.E.O.; funding acquisition, F.J.E.O.

Funding

Dr. Eiroa-Orosa has received funding from the European Union’s Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 (2014–2020) under Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No 654808.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all colleagues of the Veus and Catalonia Mental Health Federations as well as the Catalan Alliance Against Stigma, Obertament, for their inputs, support and constant struggle. We also would like to thank William Bromage, Alicia Georghiades, Tim Lomas, Kirsten MacLean, Michael Rowe and Adil Qureshi for their help with the English version of the instrument.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eiroa-Orosa, F.J.; Rowe, M. Taking the concept of citizenship in mental health across countries. Reflections on transferring principles and practice to different sociocultural contexts. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L. The recovery movement: Implications for mental health care and enabling people to participate fully in life. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, C.; Noblett, J.; Parke, H.; Clement, S.; Caffrey, A.; Gale-Grant, O.; Schulze, B.; Druss, B.; Thornicroft, G. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, S.; Mantler, E.; Szeto, A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2017, 30, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schomerus, G.; Schwahn, C.; Holzinger, A.; Corrigan, P.W.; Grabe, H.J.; Carta, M.G.; Angermeyer, M.C. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012, 125, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, L.; Jormfeldt, H.; Svedberg, P.; Svensson, B. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards people with mental illness: Do they differ from attitudes held by people with mental illness? Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2011, 59, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, L.; Nieweglowski, K.; Corrigan, P.W. Structures and types of Stigma. In The Stigma of Mental Illness—End of the Story? Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lorem, G.F.; Hem, M.H.; Molewijk, B. Good coercion: Patients’ moral evaluation of coercion in mental health care. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabe, P.A.; Rollock, M.; Duncan, G.N. Teaching clinicians the practice of recovery-oriented care. In Handbook of Recovery in Inpatient Psychiatry; Singh, N.N., Barber, J.W., Van Sant, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, A.N.; Clayton, A.; Gambino, M.; Rowe, M. Social and clinical dimensions of citizenship from the mental health-care provider perspective. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2016, 39, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.C.; Levinson, D.J. Ideology, personality, and institutional policy in the mental hospital. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1956, 53, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.H.; Cohen, M.; Naranick, C.S. A validation study of the custodial mental illness ideology scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1958, 14, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Struening, E.L. Opinions about mental illness in the personnel of two large mental hospitals. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1962, 64, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffman, E.; Guinsberg, L. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Prentice-Hall: New Yok, NY, USA; London, UK; Toronto, ON, Canada, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Markowitz, F.E.; Watson, A.; Rowan, D.; Kubiak, M.A. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.M.; Dear, M.J. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophr. Bull. 1981, 7, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Rose, D.; Little, K.; Flach, C.; Rhydderch, D.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Development and psychometric properties of the Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS): A stigma-related behaviour measure. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2011, 20, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penn, D.L.; Guynan, K.; Daily, T.; Spaulding, W.D.; Garbin, C.P.; Sullivan, M. Dispelling the Stigma of Schizophrenia: What Sort of Information Is Best? Schizophr. Bull. 1994, 20, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans-lacko, S.; Little, K.; Meltzer, H.; Rose, D.; Rhydderch, D.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Mental Health Knowledge Schedule. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.G.; Cullen, F.T.; Frank, J.; Wozniak, J.F. The Social Rejection of Former Mental Patients: Understanding Why Labels Matter. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 1461–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, A.H.; Gelder, M.G.; Rix, S.; Meltzer, H.I.; Rowlands, O.J. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teachman, B.A.; Wilson, J.G.; Komarovskaya, I. Implicit and Explicit Stigma of Mental Illness in Diagnosed and Healthy Samples. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 25, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritsher, J.B.; Otilingam, P.G.; Grajales, M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 121, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Papish, A.; Modgill, G.; Patten, S. The development and psychometric properties of a new scale to measure mental illness related stigma by health care providers: The Opening Minds Scale for Health Care Providers (OMS-HC). BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, L.G.; McConnell, H.; McGrew, J.; Salyers, M.P. Explicit and implicit stigma of mental illness as predictors of the recovery attitudes of assertive community treatment practitioners. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2017, 54, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gabbidon, J.; Clement, S.; van Nieuwenhuizen, A.; Kassam, A.; Brohan, E.; Norman, I.; Thornicroft, G. Mental Illness: Clinicians’ Attitudes (MICA) Scale-Psychometric properties of a version for healthcare students and professionals. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 206, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christison, G.W.; Haviland, M.G.; Riggs, M.L. The Medical Condition Regard Scale. Acad. Med. 2002, 77, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen Danacı, A.; Balıkçı, K.; Aydın, O.; Cengisiz, C.; Uykur, A.B. The Effect of Medical Education On Attitudes Towards Schizophrenia: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2016, 27, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.C.; Angell, B.; Vidalon, T.; Davis, K. Measuring perceived procedural justice and coercion among persons with mental illness in police encounters: The Police Contact Experience Scale. J. Commun. Psychol. 2010, 38, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burra, P.; Kalin, R.; Leichner, P.; Waldron, J.J.; Handforth, J.R.; Jarrett, F.J.; Amara, I.B. The ATP 30—A scale for measuring medical students’ attitudes to psychiatry. Med. Educ. 1982, 16, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedregal, L.E.; O’Connell, M.; Davidson, L. The Recovery Knowledge Inventory: Assessment of Mental Health Staff Knowledge and Attitudes about Recovery. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2006, 30, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabe, P.A.; Fenley, G. Project GREAT Recovery Based Training Procedures Manual. Ph.D Dissertation, Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Salyers, M.P.; Rollins, A.L.; Bond, G.R.; Tsai, J.; Moser, L.; Brunette, M.F. Development of a scale to assess practitioner knowledge in providing integrated dual disorders treatment. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 34, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkin, J.R.; Steffen, J.J.; Ensfield, L.B.; Krzton, K.; Wishnick, H.; Wilder, K.; Yangarber, N. Recovery Attitudes Questionnaire: Development and evaluation. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2000, 24, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyers, M.P.; Brennan, M.; Kean, J. Provider Expectations for Recovery Scale: Refining a measure of provider attitudes. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2013, 36, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casper, E.S.; Oursler, J.; Schmidt, L.T.; Gill, K.J. Measuring practitioners’ beliefs, goals, and practices in psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2002, 25, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deane, F.P.; Goff, R.O.; Pullman, J.; Sommer, J.; Lim, P. Changes in Mental Health Providers’ Recovery Attitudes and Strengths Model Implementation Following Training and Supervision. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killaspy, H.; White, S.; Wright, C.; Taylor, T.L.; Turton, P.; Schützwohl, M.; Schuster, M.; Cervilla, J.A.; Brangier, P.; Raboch, J.; et al. The development of the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care (QuIRC): A measure of best practice for facilities for people with longer term mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strating, M.M.H.; Broer, T.; van Rooijen, S.; Bal, R.A.; Nieboer, A.P. Quality improvement in long-term mental health: Results from four collaboratives. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, C.E.; Codd, R.T.; Terry, C. Assessing the validity of implicit and explicit measures of stigma toward clients with substance use disorders among mental health practitioners. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Finnerty, M. Recovery-Oriented Practices Index (ROPI); University of Minnesota: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, M.; Tondora, J.; Croog, G.; Evans, A.; Davidson, L. From Rhetoric to Routine: Assessing Perceptions of Recovery-Oriented Practices in a State Mental Health and Addiction System. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2005, 28, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, G. Exploring the effect of a middle response category on response style in attitude measurement. Qual. Quant. 2008, 42, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. An Introduction to Psychometric Theory with Applications in R. Available online: https://personality-project.org/r/book/ (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizopoulos, D. ltm: An R package for latent variable modeling and item response theory analyses. J. Stat. Softw. 2006, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, R.P. mirt: A Multidimensional Item Response Theory Package for the R Environment. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A language and Environment For Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Penn, D.L.; Kommana, S.; Mansfield, M.; Link, B.G. Dispelling the Stigma of Schizophrenia: II. The Impact of Information on Dangerousness. Schizophr. Bull. 1999, 25, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, S.A.; George, L.; O’Connell, M.; Sylvestre, J.; Kirkpatrick, H.; Browne, G.; Odueyungbo, A.O.; Davidson, L. Recovery-oriented service provision and clinical outcomes in assertive community treatment. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2011, 34, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbic, S.P.; Kidd, S.A.; Davidson, L.; McKenzie, K.; O’Connell, M.J. Validation of the Brief Version of the Recovery Self-Assessment (RSA-B) Using Rasch Measurement Theory. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2015, 38, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salyers, M.P.; Tsai, J.; Stultz, T.A. Measuring recovery orientation in a hospital setting. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2007, 31, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam, A.; Glozier, N.; Leese, M.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Development and responsiveness of a scale to measure clinicians’ attitudes to people with mental illness (medical student version). Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 122, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albee, G.W.; Joffe, J.M. Mental Illness Is NOT “an Illness Like Any Other”. J. Prim. Prev. 2003, 24, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J.; Haslam, N.; Sayce, L.; Davies, E. Prejudice and schizophrenia: A review of the “mental illness is an illness like any other” approach. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 114, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molewijk, B.; Kok, A.; Husum, T.; Pedersen, R.; Aasland, O. Staff’s normative attitudes towards coercion: The role of moral doubt and professional context—A cross-sectional survey study. BMC Med. Ethics 2017, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlin, I.N. Resistance to change in mental health professionals. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1969, 39, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.; Pilgrim, D. ‘Pulling down churches’: Accounting for the British Mental Health Users’ Movement. Sociol. Health Ill. 1991, 13, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, C. Towards Critical Social Work Practice in Mental Health. J. Progr. Hum. Serv. 2003, 14, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, F.L.; McCullough, C.S.; Timmons, M.E. A Synthesis of What We Know About the Use of Physical Restraints and Seclusion with Patients in Psychiatric and Acute Care Settings: 2003 Update. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2003, 10, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, S.B.; Jensen, T.N.; Bolwig, T.; Olsen, N.V. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism following physical restraint. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2005, 111, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.S. Deep venous thrombosis and fatal pulmonary embolism in a physically restrained patient. Ugeskr. Laeger 2005, 167, 2294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morrison, A.; Sadler, D. Death of a Psychiatric Patient during Physical Restraint. Excited Delirium—A Case Report. Med. Sci. Law 2001, 41, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulet, M.-H.; Larue, C.; Dumais, A. Evaluation of seclusion and restraint reduction programs in mental health: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 31, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, J.; Goldstein, R. The economic cost of using restraint and the value added by restraint reduction or elimination. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005, 56, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, J. Can paternalism be justified in mental health care? J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 28, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelto-Piri, V.; Engström, K.; Engström, I. Paternalism, autonomy and reciprocity: Ethical perspectives in encounters with patients in psychiatric in-patient care. BMC Med. Ethics 2013, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, D.; Young, M.; Caplan, A. Defining mental illnesses: Can values and objectivity get along? BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, H. Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2006, 19, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overton, S.L.; Medina, S.L. The Stigma of Mental Illness. J. Couns. Dev. 2008, 86, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.N.; Barber, J.W.; Van Sant, S. Handbook of Recovery in Inpatient Psychiatry; Singh, N.N., Barber, J.W., Van Sant, S., Eds.; Evidence-Based Practices in Behavioral Health; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-40535-3. [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft, G.; Rose, D.; Kassam, A.; Kassman, A. Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2007, 19, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, S.; McMillan, J.; Comley, Z.; Smith, A.; Brayley, J. Mental health recovery and voting: Why being treated as a citizen matters and how we can do it. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P.W. Best Practices: Strategic Stigma Change (SSC): Five Principles for Social Marketing Campaigns to Reduce Stigma. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 824–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Treaty Ser. 2006, 2515, 3. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).