Comparison of the Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Vulnerable and Non-Vulnerable Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Types of Studies

2.2.2. Types of Participants

2.2.3. Types of Outcome

- Depressive symptoms measured by validated tools such as Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [24], Beck’s Depression Inventory II (BDI) [25], Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [26], Depression subscale of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [27], and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [28];

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Assessment of Study Quality

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Publication Bias

3. Results

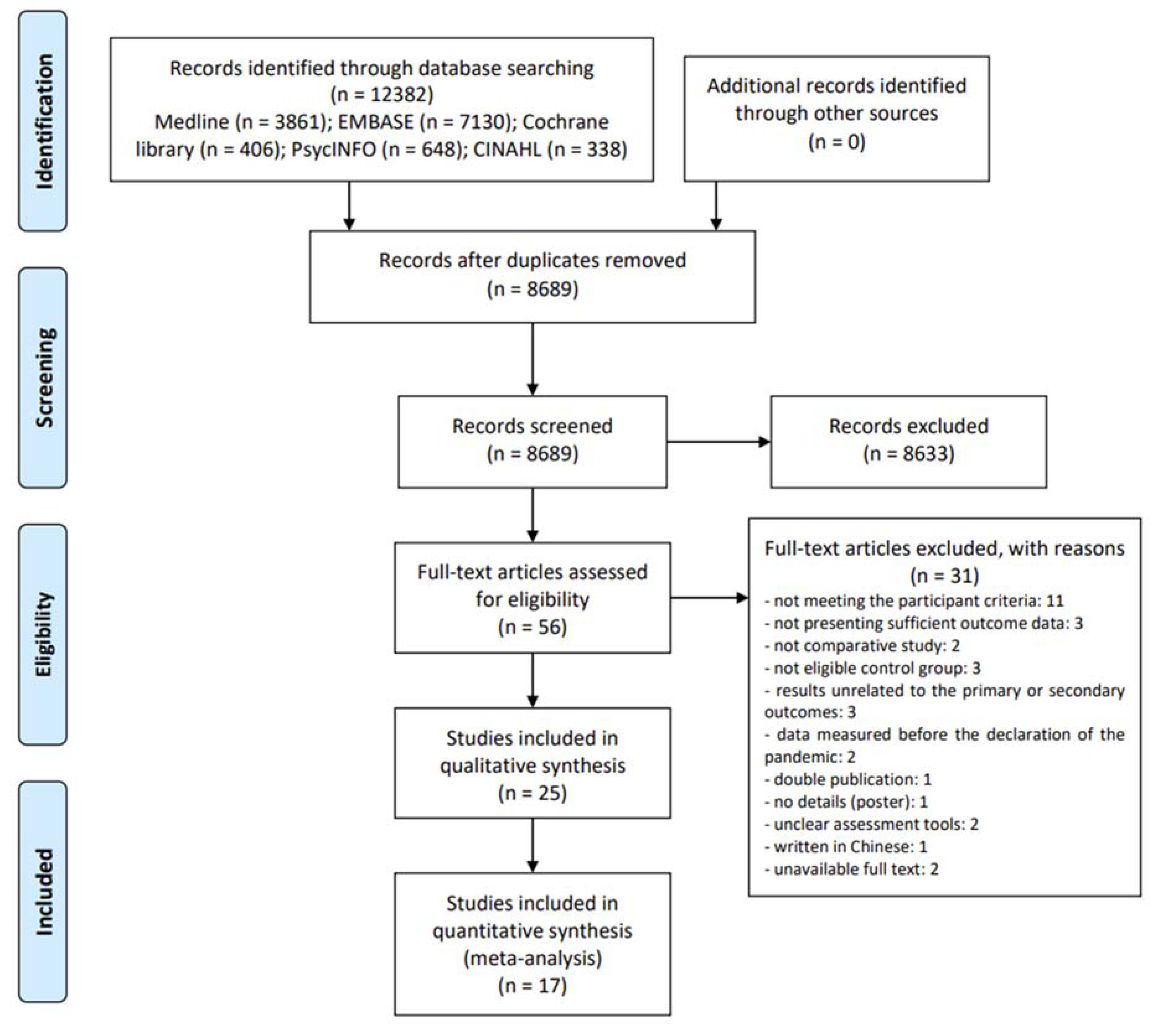

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Methodological Qualities of Included Studies

3.4. Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Vulnerable Groups

3.4.1. Depressive Symptoms: Primary Outcome

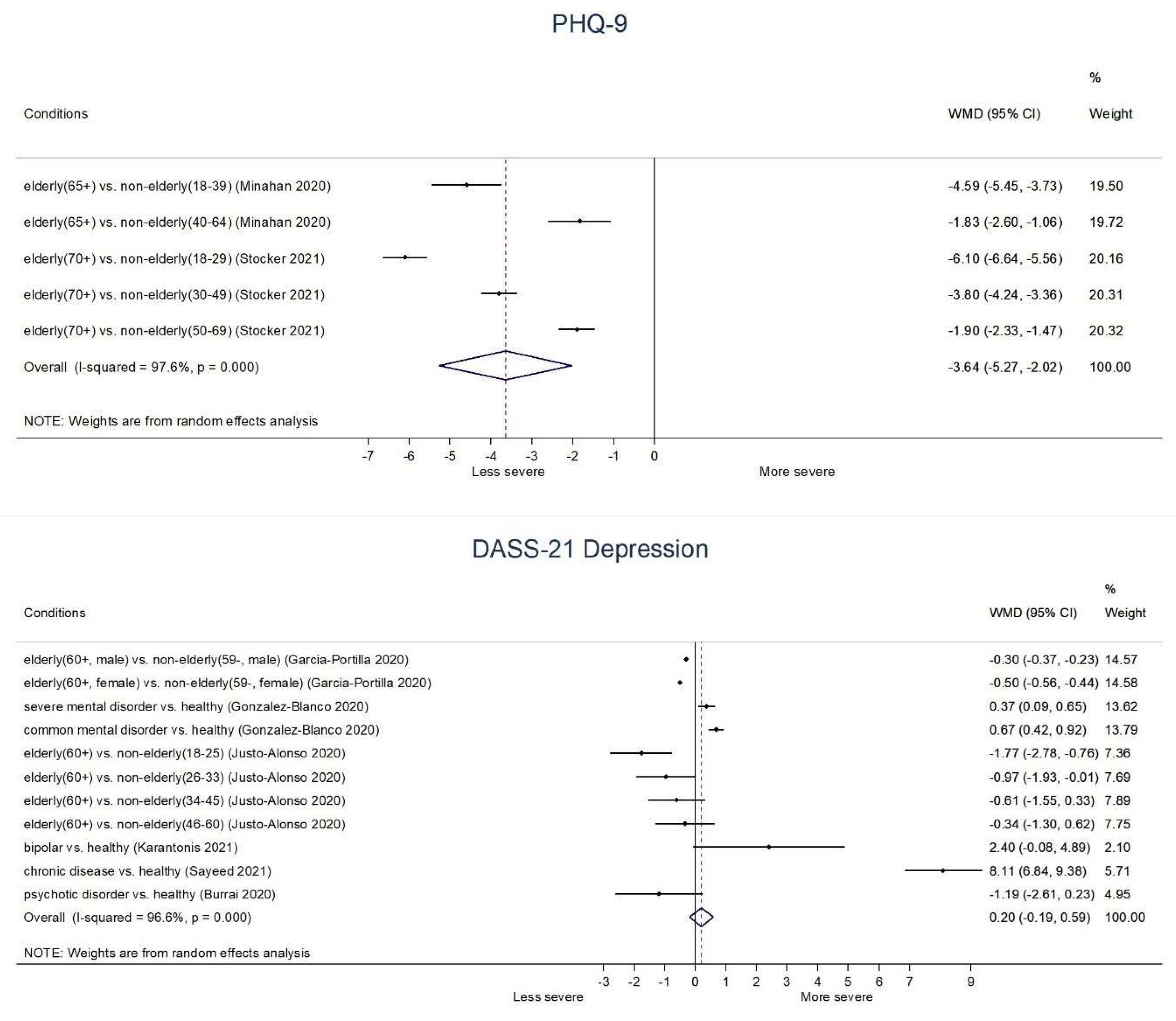

- Elderly: In the context of COVID-19, elderly (65+ or 70+) groups generally showed significantly lower depressive symptoms than non-elderly groups on PHQ-9 (WMD −4.59, 95% CI: −5.45 to −3.73 (65+ vs. 18–39 age); −1.84, −2.60 to −1.06 (65+ vs. 40–64 age); −6.10, −6.64 to −5.56 (70+ vs. 18–29 age); −3.80, −4.24 to −3.36 (70+ vs. 30–49 age); −1.90, −2.33 to −1.47 (70+ vs. 50–69 age)) as well as DASS-21 Depression score (−1.77, −2.78 to −0.76 (60+ vs. 18–25 age)); (−0.97, −1.93 to −0.01 (60+ vs. 26–33 age)). In addition, there was borderline significance between elderly (60+) group and 34–45 age group (−0.61, −1.55 to 0.33) or 46–60 age group (−0.34, −1.30 to 0.62) on DASS-21 Depression score. Moreover, both male elderly (60+) (−0.30, −0.37 to −0.23) and female elderly (60+) (−0.50, −0.56 to −0.44) showed significantly lower DASS-21 Depression score than male non-elderly (59−) and female non-elderly (59−), respectively (Figure 2).

- Chronic disease: Patients with pulmonary hypertension patients (PHQ-4: 2.30, 1.58 to 3.02), patients with chronic disease (DASS-21 Depression: 8.11, 6.84 to 9.38), and patients with Parkinson’s disease (HADS-Depression: 1.07, 0.13 to 2.01) showed significantly higher depressive symptoms than healthy control. However, there was no significant difference between patients taking immune suppressants compared to healthy control in the HADS-Depression score (−0.22, −1.98 to 1.54) (Figure 2, Supplementary File S4).

- Severe mental illness: Patients with SMI (CES-D: 7.71, 5.70 to 9.72; DASS-21 Depression: 0.37, 0.09 to 0.65) and patients with common mental disorder (DASS-21 Depression: 0.67, 0.42 to 0.92) showed significantly higher depressive symptoms than healthy control. In addition, there was borderline significance between patients with bipolar disorder and healthy control (DASS-21 Depression score: 2.40, −0.08 to 4.89), and patients with psychotic disorder and healthy control (DASS-21 Depression score: −1.19, −2.61 to 0.23) (Figure 2).

- Pregnant: Pregnant women showed significantly higher depressive symptoms than non-pregnant women on DASS-21 Depression (1.47, 0.78 to 2.16), but not on BDI-II (0.79, −0.68 to 2.26) (Supplementary File S4).

3.4.2. Anxiety: Primary Outcome

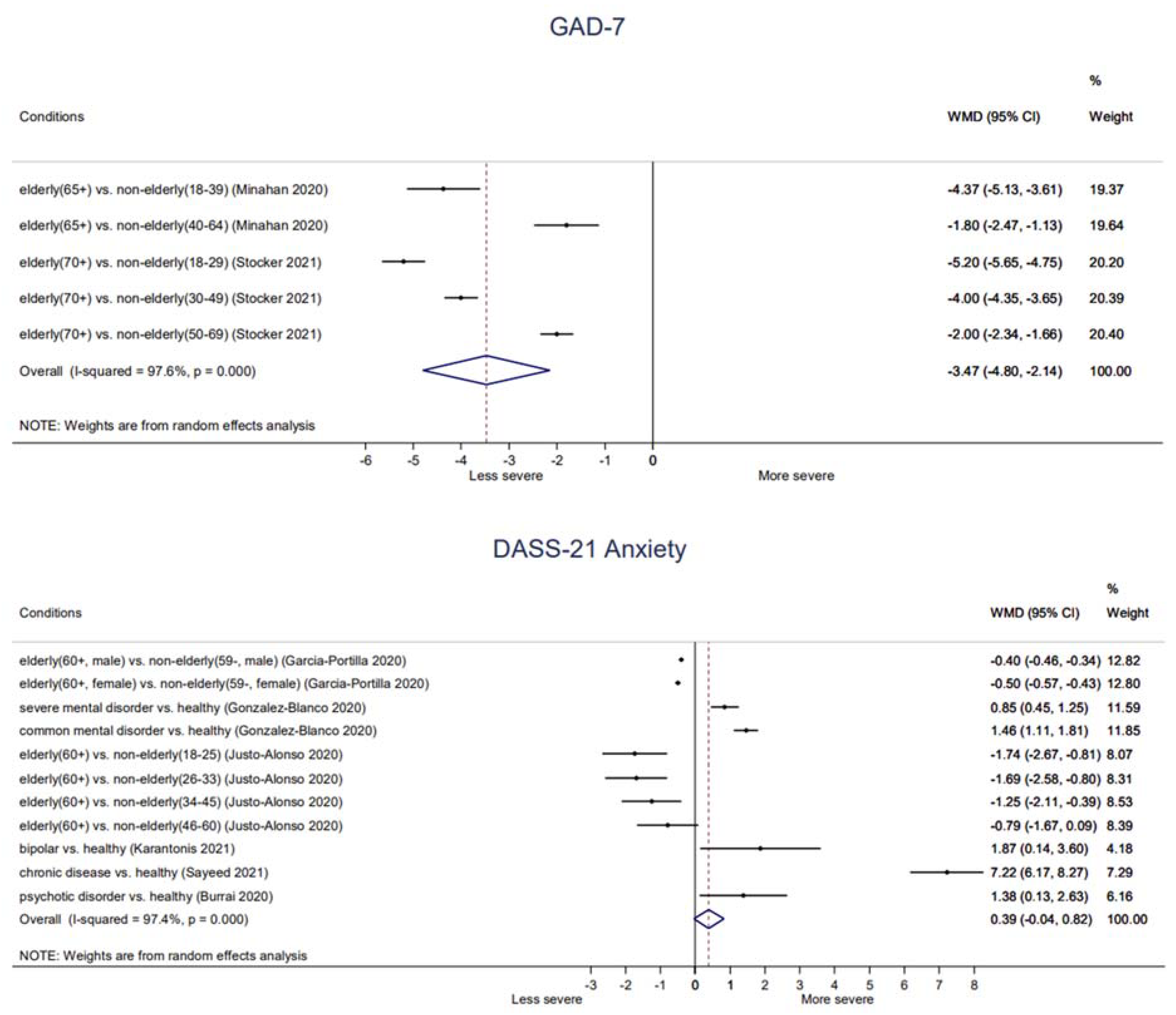

- Elderly: Elderly (65+ or 70+) groups generally showed significantly lower anxiety symptoms than non-elderly groups on GAD-7 (−4.37, −5.13 to −3.61 (65+ vs. 18–39 age); −1.80, −2.47 to −1.13 (65+ vs. 40–64 age); −5.20, −5.65 to −4.75 (70+ vs. 18–29 age); −4.00, −4.35 to −3.65 (70+ vs. 30–49 age); −2.00, −2.34 to −1.66 (70+ vs. 50–69 age)) as well as on DASS-21 Anxiety score (−1.74, −2.67 to −0.81 (60+ vs. 18–25 age); −1.69; −2.58 to −0.80 (60+ vs. 26–33 age); −1.25; −2.11 to −0.39 (60+ vs. 34–45 age)). In addition, there was borderline significance between elderly (60+) group and 40–60 age group (−0.79, −1.67 to 0.09) on DASS-21 Anxiety score. Moreover, both male elderly (60+) (−0.40, −0.46 to −0.34) and female elderly (60+) (−0.50, −0.57 to −0.43) showed significantly lower DASS-21 Anxiety score than male non-elderly (59−) and female non-elderly (59−), respectively (Figure 3).

- Chronic diseases: There were no significant differences between patients taking immune suppressants (1.38, −0.31 to 3.07) or patients with Parkinson’s disease (0.27, −0.62 to 1.16) compared to healthy control on HADS-Anxiety score. In addition, children with chronic illness (STAI-S: −2.64, −7.90 to 2.62) or children with cystic fibrosis (STAI-S: −1.00, −5.79 to 3.79) did not show significantly different state anxiety compared to healthy peers. However, children with chronic illness showed significantly higher trait anxiety (STAI-T: 6.23, 0.55 to 11.91) than that of healthy peers. Patients with chronic disease showed significantly higher anxiety symptoms (DASS-21 Anxiety: 7.22, 6.17 to 8.27) than that of healthy control (Figure 3, Supplementary File S4).

- Severe mental illness: Patients with SMI (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Anxiety: 3.71, 2.34 to 5.08; DASS-21 Anxiety: 0.85, 0.45 to 1.25), patients with bipolar disorder (DASS-21 Anxiety: 1.87, 0.14 to 3.60), patients with psychotic disorder (DASS-21 Anxiety: 1.38, 0.13 to 2.63), and patients with common mental disorder (DASS-21 Anxiety: 1.46, 1.11 to 1.81) showed significantly higher anxiety symptoms than healthy control (Figure 3).

- Pregnant: There were two conflicting results on state anxiety between pregnant and non-pregnant participants, that one found that that of pregnant women was significantly lower than that of non-pregnant women (STAI-S: −4.66; −7.32 to −2.00), while the other one found no significant difference (STAI-S: 1.15; −1.31 to 3.61). Otherwise, trait anxiety (STAI-T: −3.46, −6.12 to −0.80) and anxiety symptoms (HADS-Anxiety: 0.80, 0.09 to 1.51) of pregnant women were significantly lower than those of non-pregnant women (Supplementary File S4).

3.4.3. Stress—Secondary Outcome

- Elderly: Elderly (60+) group showed significantly lower stress symptoms than non-elderly groups on DASS-21 Stress score (−3.37, −4.67 to −2.07 (60+ vs. 18–25 age); −2.97, −4.23 to −1.71 (60+ vs. 26–33 age), −2.65, −3.87 to −1.43 (60+ vs. 34–45 age), −1.54, −2.78 to −0.30 (60+ vs. 46–60 age)). In addition, both male elderly (60+) (−1.00, −1.11 to −0.89) and female elderly (60+) (−1.40, −1.52 to −1.28) showed significantly lower DASS-21 Stress score than male non-elderly (59−) and female non-elderly (59−), respectively (Supplementary File S4).

- Chronic disease: Patients with chronic disease showed significantly higher stress symptoms than healthy control on DASS-21 Stress score (8.72, 7.47 to 9.97) (Supplementary File S4).

- Severe mental illness: Patients with SMI (PSS: 1.84, 0.68 to 3.00; DASS-21 Stress: 0.42, 0.94 to 0.10) and patients with bipolar disorder (DASS-21 Stress: 2.91, 0.31 to 5.50) showed significantly higher stress symptoms than healthy control. However, patients with psychotic disorder showed significantly lower stress symptoms than healthy control on DASS-21 Stress (1.98, 3.50 to −0.46). Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in common mental disorder patients compared to healthy control in the DASS-21 Stress (0.19, −0.29 to 0.67) (Supplementary File S4).

3.4.4. PTSD—Secondary Outcome

- Elderly: Elderly (60+ or 65+) groups generally showed significantly lower PTSD symptoms than non-elderly groups on IES Total score (−0.38, −0.48 to −0.28 (65+ vs. 18–39 age); −0.16, −0.25 to −0.07 (65+ vs. 40–64 age)), IES-R Total score (−5.18, −8.39 to −1.97 (60+ vs. 18–25 age); −5.02, −8.17 to −1.87 (60+ vs. 26–33 age); −4.07, −7.16 to −0.98 (60+ vs. 34–45 age)), IES-R Hyperactivation score (−1.88, −2.86 to −0.90 (60+ vs. 18–39 age); −1.81, −2.77 to −0.85 (60+ vs. 26–33 age); −1.53, −2.47 to −0.59 (60+ vs. 34–45 age)), IES-R Evitation score (−2.10, −3.37 to −0.83 (60+ vs. 18–25 age); −1.48, −2.72 to −0.24 (60+ vs. 26–33 age)), and IES-R Intrusions score (−1.73, −3.15, −0.31 (60+ vs. 26–33 age); 1.37, −2.76 to 0.02 (60+ vs. 34–45 age)). Moreover, both male (60+) and female elderly (60+) showed significantly lower PTSD symptoms than their non-elderly counterparts (IES-Intrusive thoughts: −0.30, −0.41 to −0.19 (male 60+ vs. male 59−); −0.40, −0.52 to −0.28 (female 60+ vs. female 59−); IES-Avoidant Behavior: −0.20, 0.34 to −0.06 (male 60+ vs. male 59−); 0.60, −0.73 to −0.47 (female 60+ vs. female 59−)). A borderline significant difference was found between elderly (60+) and 34–45 age group (−1.17, −2.39 to 0.05) on IES-R Evitation. However, no significant difference was found between elderly (60+) and 46–60 age group (IES-R Total: −1.70, −4.85 to 1.45; IES-R Hyperactivation: 0.90, −1.85 to 0.05; IES-R Intrusions: −0.64, −2.05 to 0.77; IES-R Evitation: −0.15, −1.39 to 1.09). IES-R Intrusions score of elderly (60+) compared to that of 18–25 age group was also not significant (−1.21, −2.66 to 0.24) (Supplementary File S4).

- Severe mental illness: Patients with common mental disorder showed significantly higher intrusive thoughts and avoidant behavior than healthy control on IES-Intrusive thoughts (1.06, 0.62 to 1.50) and IES-Avoidant Behavior score (0.96, 0.52 to 1.40), respectively. In addition, there was borderline significance between SMD patients and healthy control on IES-Intrusive thoughts (0.44, −0.04 to 0.92). However, patients with SMI showed significantly lower avoidant behavior than healthy control (IES-Avoidant Behavior: −0.82, −1.32 to −0.32) (Supplementary File S4).

3.4.5. Sleep—Secondary Outcome

3.4.6. Positive/Negative Affect—Secondary Outcome

3.5. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. The Findings

4.2. Clinical Interpretation

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Suggestion of Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva Junior, F.; Sales, J.; Monteiro, C.F.S.; Costa, A.P.C.; Campos, L.R.B.; Miranda, P.I.G.; Monteiro, T.A.S.; Lima, R.A.G.; Lopes-Junior, L.C. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of young people and adults: A systematic review protocol of observational studies. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, G.; Iosco, C.; Taruschio, G. Mental Health and COVID-19: An Action Plan. 2020. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202004.0197/v1 (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Rubin, G.J.; Wessely, S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. BMJ 2020, 368, m313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajkumar, R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 52, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, S.; Zeev, A.; Ophir, M.; Eilat-Adar, S. Physical activity, resilience, emotions, moods, and weight control of older adults during the COVID-19 global crisis. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, S.; Rezeppa, T.; Thoma, B.; Marengo, L.; Krancevich, K.; Chiyka, E.; Hayes, B.; Goodfriend, E.; Deal, M.; Zhong, Y.; et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Blais-Rochette, C.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Noorishad, P.G.; Mukunzi, J.N.; McIntee, S.E.; Dalexis, R.D.; Goulet, M.A.; Labelle, P.R. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APA. One Year Later, a New Wave of Pandemic Health Concerns. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2021/one-year-pandemic-stress (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Jimenez, M.; Hormeño-Holgado, A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.B.; Benitez-Agudelo, J.C.; Perez-Palencia, N.; Laborde-Cárdenas, C.C.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic in public mental health: An extensive narrative review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health ATLAS 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241514019 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Lee, D.T.; Sahota, D.; Leung, T.N.; Yip, A.S.; Lee, F.F.; Chung, T.K. Psychological responses of pregnant women to an infectious outbreak: A case-control study of the 2003 SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 61, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmerswaal, D.; Muris, P. Children’s fear reactions to the 2009 Swine Flu pandemic: The role of threat information as provided by parents. J. Anxiety Disord. 2011, 25, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, Z.; Tian, W.; Liu, W.; Cao, Y.; Yan, J.; Shun, Z. Are the elderly more vulnerable to psychological impact of natural disaster? A population-based survey of adult survivors of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meyer, M.A. Elderly Perceptions of Social Capital and Age-Related Disaster Vulnerability. Disaster. Med. Public Health Prep. 2017, 11, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lancet, T. Redefining vulnerability in the era of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009, 3, e123–e130. [Google Scholar]

- Kuy, S.; Tsai, R.; Bhatt, J.; Chu, Q.D.; Gandhi, P.; Gupta, R.; Gupta, R.; Hole, M.K.; Hsu, B.S.; Hughes, L.S.; et al. Focusing on Vulnerable Populations During COVID-19. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, e2–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Wilson, M. COVID-19: A potential public health problem for homeless populations. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e186–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. People with Certain Medical Conditions. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- de Miranda, D.M.; da Silva Athanasio, B.; de Sena Oliveira, A.C.; Silva, A.C.S. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Beck Depression Inventory: BDI-II: Manual; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; Psychology Foundation of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marteau, T.M.; Bekker, H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 31, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M.; Wilner, N.; Alvarez, W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom. Med. 1979, 41, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cameron, R.P.; Gusman, D. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Prim. Care Psychiatry 2003, 9, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, A.C.; Hindmarch, I. The Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire in psychopharmacological investigations—A review. Psychopharmacology 1980, 71, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. The Systematic Review of Prevalence and Incidence Data; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yassa, M.; Yassa, A.; Yirmibes, C.; Birol, P.; Unlu, U.G.; Tekin, A.B.; Sandal, K.; Mutlu, M.A.; Cavusoglu, G.; Tug, N. Anxiety levels and obsessive compulsion symptoms of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Turk. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2020, 17, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Kou, L.; Zhang, G.; Han, C.; Hu, J.; Wan, F.; Yin, S.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Investigation on sleep and mental health of patients with Parkinson’s disease during the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, R.; Tran, T.; Hammarberg, K.; Nguyen, H.; Rowe, H.; Fisher, J. Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) and General Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) data contributed by 13,829 respondents to a national survey about COVID-19 restrictions in Australia. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi Dadras, M.; Ahmadzadeh, Z.; Younespour, S.; Abdollahimajd, F. Evaluation of anxiety and depression in patients with morphea taking immunosuppressive drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayeed, A.; Kundu, S.; Al Banna, M.H.; Christopher, E.; Hasan, M.T.; Begum, M.R.; Chowdhury, S.; Khan, M.S.I. Mental Health Outcomes of Adults with Comorbidity and Chronic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Matched Case-Control Study. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinkham, A.E.; Ackerman, R.A.; Depp, C.A.; Harvey, P.D.; Moore, R.C. COVID-19-related psychological distress and engagement in preventative behaviors among individuals with severe mental illnesses. npj Schizophr. 2021, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinar Senkalfa, B.; Sismanlar Eyuboglu, T.; Aslan, A.T.; Ramasli Gursoy, T.; Soysal, A.S.; Yapar, D.; Ilhan, M.N. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety among children with cystic fibrosis and their mothers. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 2128–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, N.; Jahanian Sadatmahalleh, S.; Bahri Khomami, M.; Moini, A.; Kazemnejad, A. Sexual function, mental health, and quality of life under strain of COVID-19 pandemic in Iranian pregnant and lactating women: A comparative cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minahan, J.; Falzarano, F.; Yazdani, N.; Siedlecki, K.L. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Psychosocial Outcomes Across Age Through the Stress and Coping Framework. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, H.; Del Valle, M.V.; Canet-Juric, L.; Andrés, M.L.; Galli, J.I.; Poó, F.; Urquijo, S. Mental health of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karantonis, J.A.; Rossell, S.L.; Berk, M.; Van Rheenen, T.E. The mental health and lifestyle impacts of COVID-19 on bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justo-Alonso, A.; Garcia-Dantas, A.; Gonzalez-Vazquez, A.I.; Sanchez-Martin, M.; Del Rio-Casanova, L. How did Different Generations Cope with the COVID-19 Pandemic? Early Stages of the Pandemic in Spain. Psicothema 2020, 32, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Blanco, L.; Dal Santo, F.; García-Álvarez, L.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; Moya Lacasa, C.; Paniagua, G.; Sáiz, P.A.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Bobes, J. COVID-19 lockdown in people with severe mental disorders in Spain: Do they have a specific psychological reaction compared with other mental disorders and healthy controls? Schizophr. Res. 2020, 223, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Portilla, P.; de la Fuente Tomas, L.; Bobes-Bascaran, T.; Jimenez Trevino, L.; Zurron Madera, P.; Suarez Alvarez, M.; Menendez Miranda, I.; Garcia Alvarez, L.; Saiz Martinez, P.A.; Bobes, J. Are older adults also at higher psychological risk from COVID-19? Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobler, C.L.; Krüger, B.; Strahler, J.; Weyh, C.; Gebhardt, K.; Tello, K.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Sommer, N.; Gall, H.; Richter, M.J.; et al. Physical Activity and Mental Health of Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Muro, M.; Amadori, S.; Ardu, N.R.; Cerchiara, E.; De Fabritiis, P.; Niscola, P.; Dante, S.; Schittone, V.; Tesei, C.; Trawinska, M.M.; et al. Impact on Mental Health, Disease Management and Socioeconomic Modifications in Hematological Patients during COVID-19 Pandemia in Italy. Blood 2020, 136, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakiroglu, S.; Yeltekin, C.; Fisgin, T.; Oner, O.B.; Aksoy, B.A.; Bozkurt, C. Are the anxiety levels of pediatric hematology-oncology patients different from healthy peers during the COVID-19 outbreak? J. Pediatric Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 43, e608–e612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrai, J.; Roma, P.; Barchielli, B.; Biondi, S.; Cordellieri, P.; Fraschetti, A.; Pizzimenti, A.; Mazza, C.; Ferracuti, S.; Giannini, A.M. Psychological and Emotional Impact of Patients Living in Psychiatric Treatment Communities during Covid-19 Lockdown in Italy. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, Z.; Peng, S.; Wang, R.; Qi, L.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Ren, Y.; Song, X.; et al. The prevalence of psychiatric symptoms of pregnant and non-pregnant women during the COVID-19 epidemic. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sofiani, M.E.; Albunyan, S.; Alguwaihes, A.M.; Kalyani, R.R.; Golden, S.H.; Alfadda, A. Determinants of mental health outcomes among people with and without diabetes during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Arab Gulf Region. J. Diabetes 2021, 13, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciprandi, R.; Bonati, M.; Campi, R.; Pescini, R.; Castellani, C. Psychological distress in adults with and without cystic fibrosis during the COVID-19 lockdown. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021, 20, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, B.; Aktar, B.; Buran, S.; Tas, M.; Donmez Colakoglu, B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity, anxiety, and depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2021, 44, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; de Rooij, B.H.; Horevoorts, N.J.E.; May, A.M.; Vink, G.R.; Koopman, M.; van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Besselink, M.G.; Oerlemans, S.; Husson, O.; et al. Perceived Care and Well-being of Patients with Cancer and Matched Norm Participants in the COVID-19 Crisis: Results of a Survey of Participants in the Dutch PROFILES Registry. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yocum, A.K.; Zhai, Y.; McInnis, M.G.; Han, P. Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown impacts: A description in a longitudinal study of bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujang, M.A.; Sa’at, N.; Bakar, T.M.I.T.A. Sample size guidelines for logistic regression from observational studies with large population: Emphasis on the accuracy between statistics and parameters based on real life clinical data. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, J.E. Response rates and responsiveness for surveys, standards, and the Journal. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Sousa, A.; Mohandas, E.; Javed, A. Psychological interventions during COVID-19: Challenges for low and middle income countries. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 51, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, F.; González-Blanco, L.; García-Álvarez, L.; la Fuente-Tomás, L.; Moya-Lacasa, C.; Paniagua, G.; Valtueña-García, M.; Martín-Gil, E.; Álvarez-Vázquez, C.; Sáiz, P.P. 859COVID-19 lockdown in people with severe mental disorders in Spain: Do they have a specific psychological reaction? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 40, S475–S476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleskey, J.; Gruda, D. Risk-taking, resilience, and state anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: A coming of (old) age story. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 170, 110485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Alhazmi, A.K.; Mohammed, F.; Gazem, N.A.; Shabbir, M.S.; Fazea, Y. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ learning life: An integrated conceptual motivational model for sustainable and healthy online learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.R.; Agho, K.E.; Stevens, G.J.; Raphael, B. Factors influencing psychological distress during a disease epidemic: Data from Australia’s first outbreak of equine influenza. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ko, C.H.; Yen, C.F.; Yen, J.Y.; Yang, M.J. Psychosocial impact among the public of the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 60, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wańkowicz, P.; Szylińska, A.; Rotter, I. Insomnia, Anxiety, and Depression Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic May Depend on the Pre-Existent Health Status Rather than the Profession. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druss, B.G. Addressing the COVID-19 Pandemic in Populations with Serious Mental Illness. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 891–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alipour, Z.; Kheirabadi, G.R.; Kazemi, A.; Fooladi, M. The most important risk factors affecting mental health during pregnancy: A systematic review. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 24, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunier, A.; Drysdale, C. COVID-19 Disrupting Mental Health Services in Most Countries, WHO Survey; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, Y.; Finnie, T. Culture counts: The diverse effects of culture and society on mental health amidst COVID-19 outbreak in Australia. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibson, B.A.; Ghosh, D.; Morano, J.P.; Altice, F.L. Accessibility and utilization patterns of a mobile medical clinic among vulnerable populations. Health Place 2014, 28, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dorz, S.; Borgherini, G.; Conforti, D.; Scarso, C.; Magni, G. Comparison of self-rated and clinician-rated measures of depressive symptoms: A naturalistic study. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2004, 77, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogia, J.; Kulatunga, U.; Yates, G.; Wedawatta, G. Culture and the psychological impacts of natural disasters: Implications for disaster management and disaster mental health. Built. Hum. Environ. Rev. 2014, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hennein, R.; Mew, E.J.; Lowe, S.R. Socio-ecological predictors of mental health outcomes among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldmann, E.; Hagen, D.; El Khoury, E.; Owens, M.; Misra, S.; Thrul, J. An examination of racial and ethnic disparities in mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic in the US South. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrasseur, A.; Fortin-Bédard, N.; Lettre, J.; Bussières, E.-L.; Best, K.; Boucher, N.; Hotton, M.; Beaulieu-Bonneau, S.; Mercier, C.; Lamontagne, M.-E. Impact of COVID-19 on people with physical disabilities: A rapid review. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 14, 101014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, H.; Miller, W.C.; Esfandiari, E.; Mohammadi, S.; Rash, I.; Tao, G.; Simpson, E.; Leong, K.; Matharu, P.; Sakakibara, B. The Impact of COVID-19–Related Restrictions on Social and Daily Activities of Parents, People with Disabilities, and Older Adults: Protocol for a Longitudinal, Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e28337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesbrecht, G.F.; Bagshawe, M.; van Sloten, M.; MacKinnon, A.L.; Dhillon, A.; van de Wouw, M.; Vaghef-Mehrabany, E.; Rojas, L.; Cattani, D.; Lebel, C. Protocol for the Pregnancy During the COVID-19 Pandemic (PdP) Study: A Longitudinal Cohort Study of Mental Health Among Pregnant Canadians During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Developmental Outcomes in Their Children. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e25407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Snoswell, C.L.; Harding, L.E.; Bambling, M.; Edirippulige, S.; Bai, X.; Smith, A.C. The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemed. e-Health 2020, 26, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizheh, M.; Qorbani, M.; Arzaghi, S.M.; Muhidin, S.; Javanmard, Z.; Esmaeili, M. The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Hu, C.; Feng, R.; Yang, Y. Investigation of the Mental Health of Patients with Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. Chin. J. Neurol. 2020, 12, E003. [Google Scholar]

- Egede, L.E.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Frueh, B.C. Ensuring mental health access for vulnerable populations in COVID era. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 129, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, R.G.; White, K.; Lehman, D.R. Culture, stress, and coping: Internally-and externally-targeted control strategies of European Canadians, East Asian Canadians, and Japanese. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2004, 35, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study Design | Country | Ethnicity | Type of Vulnerability | Sample Size (M:F) | Mean Age (Year) | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yassa 2020 | prospective CC | Turkey | NR | Pregnant | G1 (pregnant): 203 G2 (non-pregnant):101 | G1: 27.4 ± 5.3 G2: 27.6 ± 4.1 | 1. STAI 20-item | 1-1. state anxiety: G1 > G2 + 1-2. trait anxiety: NS |

| García-Portilla 2020 | CS | Spain | NR | Elderly | G1 (60+): 1690 (831:859) G2 (59−): 13,363 (4308:9055) | G1: 65.9 ± 5.1 G2: (male) 66.5 ± 5.4, (female) 64.4 ± 4.8 | 1. DASS-21 2. IES | Female/Male 1-1. depression: G1 < G2 +/G1 < G2 + 1-2. anxiety: G1 < G2 +/G1 < G2 + 1-3. stress: G1 < G2 +/G1 < G2 + 2-1. intrusive thoughts: G1 < G2 +/G1 < G2 + 2-2. avoidant behavior: G1 < G2 +/G1 < G2 + |

| Cakiroglu 2020 | CS | Turkey | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients):15 G2 (healthy control): 33 | G1: 15.80 ± 2.11 G2: 15.00 ± 2.5 | 1. STAI 20-item | 1-1. state anxiety: NS 1-2. trait anxiety: G1 > G2 + |

| González-Blanco 2020 | CS | Spain | NR | SMI | G1 (SMI): 125 (48:77) G2 (CMD): 250 (96:154) G3 (HC): 250 (96:154) | G1: 43.25 ± 14.41 G2: 43.17 ± 14.27 G3: 43.27 ± 14.37 | 1. DASS-21 2. IES | 1-1. depression: G3 < G1 < G2 + 1-2. anxiety: G3 < G1 < G2 + 1-3. stress: G3 < G1 < G2 + 2-1. intrusive thoughts: G3 < G1 < G2 + 2-2. avoidant behavior: G1 < G3 < G2 + |

| Yocum 2021 | LS | United States | Multiethnicity | SMI | G1 (BD): 345 G2 (HC): 147 | G1, G2: 49 | 1. PHQ-9 2. GAD-7 3. PSQI | 1. depression: G1 > G2 § 2. anxiety: G1 > G2 § 3. sleep: G1 > G2 § |

| Minahan 2020 | CS | United States | Multiethnicity | Elderly | G1 (18–39): 375 G2 (40–64): 542 G3 (65–92): 398 | G1: 27.98 ± 5.18 G2: 55.44 ± 6.51 G3: 71.32 ± 5.10 | 1. PHQ-9 2. GAD-7 3. IES | 1. depression: G3 < G2 < G1 § 2. anxiety: G3 < G2 < G1 § 3. PTSD: G3 < G2 < G1 § |

| Pinkham 2021 | CS | United States | NR | SMI | G1 (SMI): 163 (64:99) G2 (HC): 27 (13:14) | G1: 42.74 ± 11.26 G2: 38.41 ± 12.24 | 1. CES-D 2. PSS 3. PROMIS-anxiety | 1. depression: G1 > G2 § 2. stress: G1 > G2 § 3. anxiety: G1 > G2 § |

| Al-Sofiani 2020 | CS | Saudi Arabia | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 568 (242:326) G2 (HC): 1598 (632:966) | NR | 1. PHQ-9 2. GAD-7 | 1. depression: G1 > G2 § 2. anxiety: G1 > G2 § |

| Senkalfa 2020 | CS | Turkey | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 45 (23:22) G2 (HC): 90 (46:44) | Median (IQR) G1: 99.0 mo (63.3–139.5) G2: 106.7 mo (53.0–159.1) | 1. STAI-C | 1. anxiety: G1 < G2 § |

| Dadra 2020 | retrospective CC | Iran | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 42 (8:34) G2 (HC): 42 (13:29) | Median (IQR) G1: 32 (24.5–47.75) G2: 37 (32–45.25) | 1. HADS | 1-1. anxiety: NS 1-2. depression: NS |

| Justo-Alonso 2020 | CS | Spain | NR | Elderly | G1 (18–25): 458 G2 (26–33): 729 G3 (34–45): 1358 G4 (46–60): 749 G5 (60−): 204 | G1, G2: 39.24 ± 12.00 | 1. DASS-21 2. IES-R | 1-1. depression: G5 < G4 < G3 < G2 < G1 + 1-2. anxiety: G5 < G4 < G3 < G2 < G1 + 1-3. stress: G5 < G4 < G3 < G2 < G1 + 2. G5 < G4 < G3 < G2 < G1 + |

| Balci 2021 | retrospective CC | Turkey | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 45 (30:15) G2 (HC): 43 (24:19) | Median (IQR) G1: 67 (60.00–73.50) G2: 66 (58.00–71.00) | 1. HADS | 1-1. depression: NS 1-2. anxiety: NS |

| Muro 2020 | CS | Italy | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 1113 G2 (HC): 1125 | Range G1: 11–93 G2: 13–85 | 1. DASS-21 | 1-1. depression: G1 > G2 § 1-2. anxiety: G1 > G2 § 1-3. stress: G1 > G2 § |

| Xia 2020 | CS | China | single ethnicity | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 119 (61:58) G2 (HC): 169 (76:93) | G1: 61.18 ± 8.77 G2: 59.84 ± 8.15 | 1. HADS 2. PSQI | 1-1. depression: G1 > G2 + 1-2. anxiety: G1 > G2 * 2. G1 > G2 + |

| Karantonis 2021 | CS | Australia | NR | SMI | Group1 (BD): 43 (19:24) Group2 (HC): 24 (11:13) | G1: 25.3 ± 11.14 G2: 22.79 ± 12.81 | 1. DASS-21 | 1-1. depression: G1 > G2 * 1-2. anxiety: G1 > G2 * 1-3. stress: G1 > G2 * |

| López-Morales 2020 | LS | Argentina | NR | Pregnant | Group1 (pregnant):102 Group2 (non-pregnant): 102 | G1: 32.59 ± 4.73 G2: 32.54 ± 4.71 | 1. BDI –II 2. STAI | 1. depression: G1 > G2 § 2. anxiety: G1 > G2 § |

| Sayeed 2021 | prospective CC | Bangladesh | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 395 (305:90) G2 (HC): 395 (305:90) | G1: 38.37 ± 12.92 G2: 36.17 ± 6.95 | 1. DASS-21 | 1-1. depression: G1 > G2 + 1-2. anxiety: G1 > G2 + 1-3. stress: G1 > G2 + |

| Stocker 2021 | CS | Australia | NR | Elderly | G1 (18–29): 1337 G2 (30–49): 5148 G3 (50–69): 5897 G 4(70+):1447 | NR | 1. PHQ-9 2. GAD-7 | 1. depression: G4 < G3 < G2 < G1 § 2. anxiety: G4 < G3 < G2 < G1 § |

| Poll-Franse 2021 | retrospective CC | Netherland | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 4094 G2 (HC): 977 | G1: 63.0 ± 11.1 G2: 62.3 ± 13.0 | 1. HADS | 1-1. depression: NS 1-2. anxiety: G1 > G2 + |

| Dobler 2020 | prospective CC | Germany | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 112 (25:87) G2 (HC): 52 (17:35) | G1: 54.4 ± 14.0 G2: 52.3 ± 8.9 | 1. PHQ-4 | 1. depression: G1 < G2 + |

| Zach 2021 | CS | Israel | NR | Elderly | G1 (45–59): 645 (182:463) G2 (60–69): 393 (138:255) G3 (70+): 164 (60:103) | NR | A questionnaire for measuring depressive moods | 1. depression: G1 > G2 > G3 + |

| Burrai 2020 | CS | Italy | NR | SMI | G1 (SMI): 77 (51:26) G2 (HC): 100 (50:50) | G1: 46.61 ± 12.81 G2: 46.40 ± 11.52 | 1. DASS-21 | 1-1. depression: NS 1-2. anxiety: G1 > G2 * 1-3. stress: G1 < G2 * |

| Ciprandi 2020 | CS | Italy | NR | Chronic disease | G1 (patients): 712 (290:422) G2 (HC): 3560 (1450:2110) | NS | 1. CPDI | 1. stress: G1 > G2 § |

| Mirzaei 2021 | CS | Iran | NR | Pregnant | G1 (pregnant): 200 G2 (non-pregnant):201 | G1: 29.69 ± 5.85 G2: 32.59 ± 6.31 | 1. HADS | 1-1. depression: G1 > G2 + 1-2. anxiety: G1 > G2 + |

| Zhou 2020 | CS | China | NR | Pregnant | G1 (pregnant): 544 G2 (non-pregnant):315 | G1: 31.1 ± 3.9 G2: 35.4 ± 5.7 | 1.PHQ-9 2. GAD-7 3. PCL-5 4. ISI | 1. depression: G1 < G2 + 2. anxiety: G1 < G2 + 2. PTSD: G1 < G2 + 3.sleep: NS |

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yassa 2020 | N | U | U | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | U |

| García-Portilla 2020 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Cakiroglu 2020 | N | U | U | U | U | Y | U | Y | U |

| González-Blanco 2020 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Yocum 2021 | N | N | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Minahan 2020 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Pinkham 2021 | Y | N | U | Y | U | Y | U | Y | U |

| Al-Sofiani 2020 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Senkalfa 2020 | N | N | U | Y | U | Y | U | Y | U |

| Dadra 2020 | N | N | N | Y | NA | Y | U | Y | NA |

| Justo-Alonso 2020 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Balci 2021 | U | U | N | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | NA |

| Muro 2020 | U | U | Y | Y | U | Y | U | N | Y |

| Xia 2020 | N | N | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Karantonis 2021 | U | U | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| López-Morales 2020 | Y | N | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Sayeed 2021 | Y | N | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Stocker 2021 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Poll-Franse 2021 | Y | U | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Dobler 2020 | N | N | U | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Zach 2021 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Burrai 2020 | N | U | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Ciprandi 2020 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | U |

| Mirzaei 2021 | U | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Zhou 2020 | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Outcomes (Compared to Control Group) | Elderly | Chronic Disease | Pregnant | SMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health outcomes | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | ↓ * | Mixed (↑ *, NS) | Mixed (↑ *, NS) | Mixed (↑ *, ↓ *) |

| Anxiety | ↓ * | Mixed (↑ *, NS) | Mixed (↓ *,↑ *, NS) | ↑ * |

| Stress | ↓ * | ↑ * | - | Mixed (↓ *,↑ *) |

| PTSD symptoms | Mixed (↓ *, NS) | - | - | Mixed † (↑ *,↓ *) |

| Sleep disturbance | - | ↑ * | - | - |

| Positive affect | - | - | NS | - |

| Negative affect | - | - | NS | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nam, S.-H.; Nam, J.-H.; Kwon, C.-Y. Comparison of the Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Vulnerable and Non-Vulnerable Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010830

Nam S-H, Nam J-H, Kwon C-Y. Comparison of the Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Vulnerable and Non-Vulnerable Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010830

Chicago/Turabian StyleNam, Soo-Hyun, Jeong-Hyun Nam, and Chan-Young Kwon. 2021. "Comparison of the Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Vulnerable and Non-Vulnerable Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 20: 10830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010830

APA StyleNam, S.-H., Nam, J.-H., & Kwon, C.-Y. (2021). Comparison of the Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Vulnerable and Non-Vulnerable Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010830