The Impact of the Gain-Loss Frame on College Students’ Willingness to Participate in the Individual Low-Carbon Behavior Rewarding System (ILBRS): The Mediating Role of Environmental Risk Perception

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Operating Status of ILBRS

1.2. Framing

1.3. Environmental Risk Perception

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.3. Experimental Method

- Collecting 2280 g of carbon energy means we can protect 1 square meter of the primeval forest which is the home of animals.

- Collecting 10,800 g of carbon energy means we can protect 10 square meters of Sanjiangyuan Park which is the home of the Chinese snow leopard

- Collecting 20,000 g of carbon energy means that one sand willow can be planted in the desert to stop the spread of the Mongolian desert by 1 square meter

- Collecting 50,000 g of carbon energy means that one camphor pine can be planted to help absorb 50 g/day of CO2 and slow down climate change.

- Collecting 80,000 g of carbon energy means we can plant an elm tree, stopping 1 square meter of arable land in the Yellow River basin from being washed away.

- Without collecting 2280 g of carbon energy, 1 square meter of virgin forest is destroyed without protection and animals lose their homes.

- Without collecting 10,800 g of carbon energy, 10 square meters of the Sanjiangyuan Park, home of the Chinese snow leopard, are destroyed due to lack of protection.

- Without collecting 20,000 g of carbon energy, 1 square meter of the Mongolian desert spreads forward due to the lack of a sand willow.

- Without collecting 50,000 g of carbon energy, the carbon dioxide we produce today worsens the climate as a result of the lack of a single camphor pine to absorb it.

- Without collecting 80,000 g of carbon energy, 1 square meter of arable land in the Yellow River basin is washed away by heavy floods due to the lack of a single elm tree to hold it in place.

- Questions on demographic variables: including gender, age, education, profession, city of residence.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Tests of Variance

3.2. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

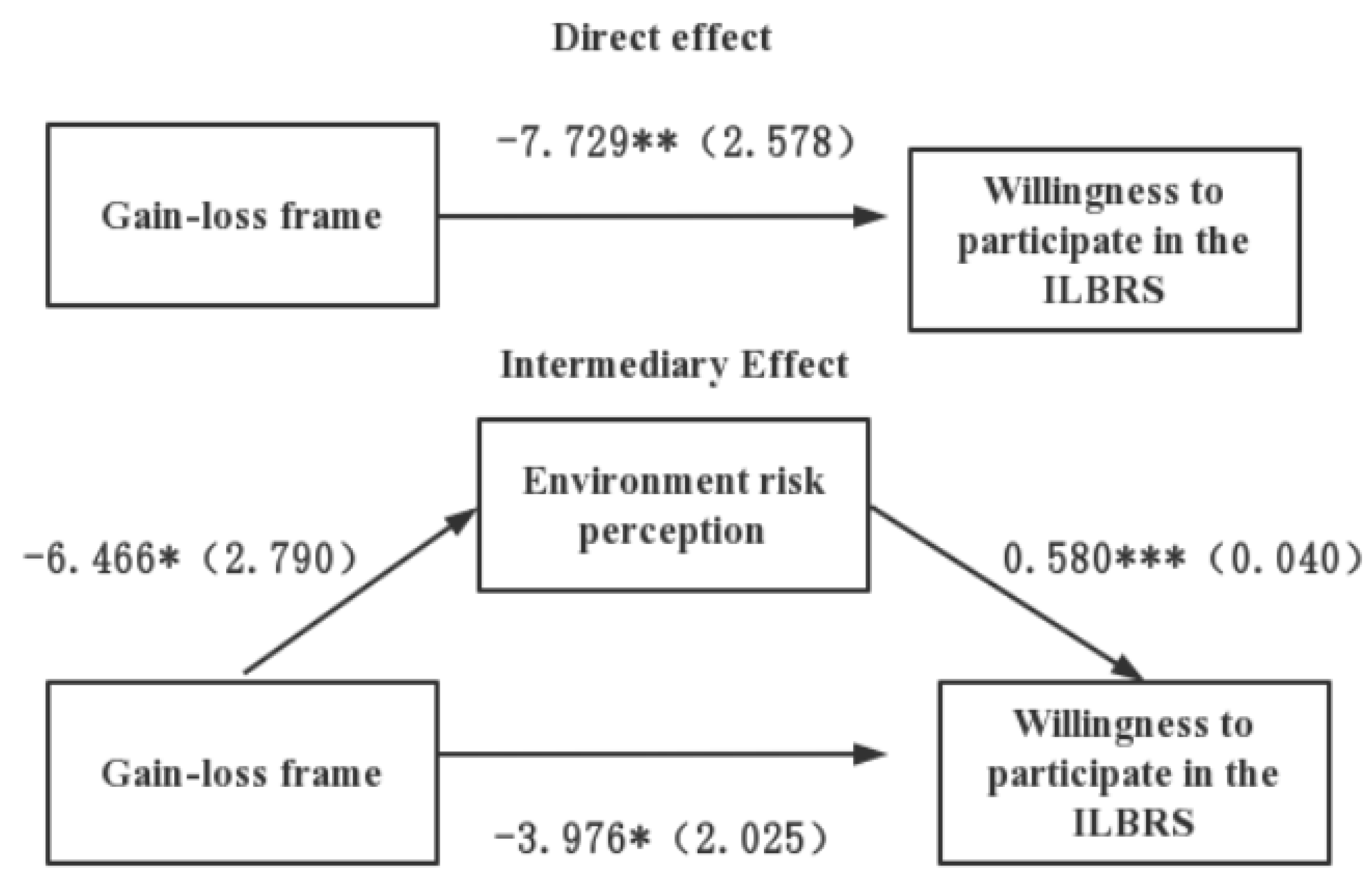

3.3. Intermediary Model Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions and Policy Recommendations

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, J.; Fan, Y.; Timilsina, G.; Xia, Y.; Guo, R. Understanding the economic impact of interacting carbon pricing and renewable energy policy in China. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2020, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Lin, B. Rethinking the choice of carbon tax and carbon trading in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 159, 120187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, T.; Chang, C.-T.; Fu, C.J. China’s renewable energy strategy and industrial adjustment policy. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 1382–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Lee, H. Taiwan’s renewable energy strategy and energy-intensive industrial policy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Sun, M.; Gong, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y. Chinese residents’ attitudes toward consumption-side climate policy: The role of climate change perception and environmental topic involvement. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Tao, L.; Wang, J. Establishing a digital carbon inclusion mechanism to promote a green revolution in lifestyle. Environ. Econ. 2021, 18, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, D.; Stadler, K.; Steen-Olsen, K.; Wood, R.; Vita, G.; Tukker, A.; Hertwich, E.G. Environmental Impact Assessment of Household Consumption. J. Ind. Ecol. 2016, 20, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zheng, S. Research on the Progress of Carbon Inclusion Mechanism Implementation in Guangdong Province. China Econ. Trade J. 2018, 8, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. How effective are eco-points in leading a green life?—An analysis of the policy design and implementation effect based on the Fuzhou Carbon Inclusion Public Service (Greenbelt) platform. China Ecol. Civiliz. 2021, 6, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y. Beijing’s Carbon Inclusion Practice: Closing the Loop on MaaS Platform with Millions of Users. 21st Century Business Herald, 26 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Song, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Mei, X. Ant Forest: An Internet practice of environmental public welfare. Tsinghua Manag. Rev. 2020, Z1, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Carbon Inclusion System Innovation: Bank’s “Personal Carbon Account” Launched Internal Test. China Securities Journal, 15 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hyper, Y. Exploring the Carbon Inclusion Mechanism for Energy-Saving Appliances to Stimulate New Motivation for Low-Carbon Living. Energy Conserv. Environ. Prot. 2022, 3, 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, W. A study on low carbon management of living based on carbon inclusiveness system—Xiong’an New Area as an example. Environ. Prot. Circ. Econ. 2022, 42, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoza, M.; Holz, J.; List, J.; Zentner, A.; Cardoza, M.; Zentner, J. The $100 Million Nudge: Increasing Tax Compliance of Businesses and the Self-Employed Using a Natural Field Experiment; Working Paper 27666; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen, R.; Andersen, A. Recommendations with a Nudge. Technologies 2019, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, M.; Mont, O.; Heiskanen, E. Nudging—A promising tool for sustainable consumption behavior? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R. Behavioral economics, consumption and environmental protection. In Handbook on Research in Sustainable Consumption; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Momsen, K.; Stoerk, T. From intention to action: Can nudges help consumers to choose renewable energy? Energy Policy 2014, 74, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Li, S.; Liang, Z. Small is big: Behavioral decision making contributes to social development. J. Psychol. 2018, 50, 803–813. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, G.M. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2009, 8, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Y. New ideas in the study of framing effects in behavioral decision making-from risky to intertemporal decision making, from verbal to graphic framing. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Xin, Z.; Lou, Z.; Gao, Y. Boost-based intervention strategies for environmental behavior. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 27, 1939–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tan, P. Applied research on frame effect and its application techniques. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropret, H.A.; Knežević, C.L. The effects of framing on environmental decisions: A systematic literature review. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhorst, J.; Klöckner, C.A.; Matthies, E. Saving electricity—For the money or the environment? Risks of limiting pro-environmental spillover when using monetary framing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlstone, M.J.; Lewandowsky, S.; Newell, B.R.; Sewell, B. The Effect of Framing and Normative Messages in Building Support for Climate Policies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, M.L.; Alhakami, A.; Slovic, P.; Johnson, S.M. The Affect Heuristic in Judgments of Risks and Benefits. J. Behav. Dec. Making 2000, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, U.; Damberg, S.; Frömbling, L.; Ringle, C.M. Sustainable Consumption Behavior of Europeans: The Influence of Environmental Knowledge and Risk Perception on Environmental Concern and Behavioral Intention. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 189, 107155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values. Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levin, I.P.; Schneider, S.L.; Gaeth, G.J. All Frames Are Not Created Equal: A Typology and Critical Analysis of Framing Effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1998, 76, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Pidgeon, N. Framing and communicating climate change: The effects of distance and outcome frame manipulations. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Whitaker, L. Promoting the Use of Reusable Coffee Cups through Environmental Messaging, the Provision of Alternatives and Financial Incentives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Framing Effects in Risky Decision Making: The Role of Immediate Emotions and Cognitive Reappraisal Strategies. Master’s Dissertation, Hunan Normal University, Hunan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Ekinci, Y.; Can, A.S.; Murray, J.C. Effectiveness of message framing in changing COVID-19 vaccination intentions: Moderating role of travel desire. Tour. Manag. 2022, 90, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.J. The Effects of Message Framing on Response to Environmental Communications. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1995, 72, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.A. Consumer Behavior as Risk Taking. In Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World, Proceedings of the 43rd Conference of the American Marketing Association; Hancock, R.S., Ed.; Marketing Classics Press: Decatur, GA, USA, 1960; pp. 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Götz, K.; Courtier, A.; Stein, M.; Strelau, L.; Sunderer, G.; Vidaurre, R.; Winker, M.; Roig, B. Chapter 8—Risk Perception of Pharmaceutical Residues in the Aquatic Environment and Precautionary Measures. In Management of Emerging Public Health Issues and Risks; Roig, B., Weiss, K., Thireau, V., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 189–224. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P. Perception of Risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiest, S.L.; Raymond, L.; Clawson, R.A. Framing, partisan predispositions, and public opinion on climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 31, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.C.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Klerkx, L. The persuasiveness of gain vs. loss framed messages on farmers’ perceptions and decisions to climate change: A case study in coastal communities of Vietnam. Clim. Risk Manag. 2022, 35, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, M. The Conquering of Climate: Discourses of Fear and Their Dissolution. Geogr. J. 2008, 174, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, A.; Jeong, D.; Chon, J. The impact of the risk perception of ocean microplastics on tourists' pro-environmental behavior intention. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 144782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominicis, S.D.; Fornara, F.; Cancellieri, U.G.; Twigger-Ross, C.; Bonaiuto, M. We are at risk, and so what? Place attachment, environmental risk perceptions and preventive coping behaviors. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G. Inclusive innovation of carbon trading mechanism. Globalization 2014, 11, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhonglin, W.; Lei, C.; Kit-Tai, H.; Hongyun, L. Testing and applicetion of the mediating effects. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2004, 36, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, T.A.; Rabinovich, A.; Marshall, D.; Bretschneider, P. The future that may (or may not) come: How framing changes responses to uncertainty in climate change communications. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Xu, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Lv, T.; Gan, X.; Shang, K.; Qiao, L. Playing Ant Forest to promote online green behavior: A new perspective on uses and gratifications. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse, R.; Gabrielyan, G.; Wolfenden, L.; Yoong, S.; Swigert, J.; Delaney, T.; Lecathelinais, C.; Ooi, J.Y.; Pinfold, J.; Just, D. Can changing the position of online menu items increase selection of fruit and vegetable snacks? A cluster randomized trial within an online canteen ordering system in Australian primary schools. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L.E.; Sadeghzadeh, C.; Koutlas, M.; Zimmer, C.; De Marco, M. Evaluation of three behavioral economics ‘nudges’ on grocery and convenience store sales of promoted nutritious foods. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 3250–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, R.; Hongyan, G.; Xiao, L. An empirical study of factors influencing public environmental behavior in China—Based on data from the 2019 Citizen Ecological and Environmental Behavior Survey. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 45, 8. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Level | Sample Size (N = 320) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 162 | 50.6 |

| Female | 158 | 49.4 | |

| Grouping | Group under loss framing | 164 | 51.3 |

| Group under gain framing | 156 | 49.7 | |

| Age | 17–25 Years old | 228 | 71.2 |

| Above 25 Years old | 92 | 28.8 | |

| Monthly living expenses | 500 RMB–1000 RMB | 39 | 12.2 |

| 1000 RMB–1500 RMB | 116 | 36.3 | |

| 1500 RMB–2000 RMB | 87 | 27.2 | |

| 2000 RMB–3000 RMB | 54 | 16.9 | |

| Above 3000 RMB | 24 | 7.5 | |

| Education | Bachelor Degree | 255 | 79.7 |

| Specialty | 33 | 10.3 | |

| Master’s Degree | 32 | 10.0 |

| Variables | M ± SD | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss Frame (N = 164) | Gain Frame (N = 156) | |||

| Willingness to participate in the ILBRS | 79.23 ± 19.03 | 71.50 ± 26.62 | 2.999 | 0.003 |

| Environment risk perception | 76.79 ± 21.99 | 70.33 ± 27.72 | 2.317 | 0.021 |

| Variables | Step 1 | Step 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 91.787 *** (11.285) | 94.607 *** (11.273) |

| Gender | −0.105 (2.624) | −0.083 (2.643) |

| Age | 0.017 (0.423) | 0.010 (0.421) |

| Education | −0.151 ** (2.918) | −0.131 (2.932) |

| Monthly living expenses | −0.025 (1.168) | −0.044 (1.174) |

| Frames | −0.133 * (2.672) | |

| F | 3.291 * | 3.743 ** |

| R2 | 0.040 | 0.056 |

| ΔR2 | 0.040 | 0.016 |

| Effect | Effect Value | Boot Standard | Low Limited of 95% | Upper Limited of 95% | Ratio of Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −7.729 | 2.578 | −12.800 | −2.658 | - |

| Direct effect | −3.976 | 2.025 | −7.960 | 0.008 | - |

| Indirect effect | −3.753 | 1.772 | −7.561 | −0.591 | 48.56% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qi, A.; Ji, Z.; Gong, Y.; Yang, B.; Sun, Y. The Impact of the Gain-Loss Frame on College Students’ Willingness to Participate in the Individual Low-Carbon Behavior Rewarding System (ILBRS): The Mediating Role of Environmental Risk Perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711008

Qi A, Ji Z, Gong Y, Yang B, Sun Y. The Impact of the Gain-Loss Frame on College Students’ Willingness to Participate in the Individual Low-Carbon Behavior Rewarding System (ILBRS): The Mediating Role of Environmental Risk Perception. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):11008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711008

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Ani, Zeyu Ji, Yuanchao Gong, Bo Yang, and Yan Sun. 2022. "The Impact of the Gain-Loss Frame on College Students’ Willingness to Participate in the Individual Low-Carbon Behavior Rewarding System (ILBRS): The Mediating Role of Environmental Risk Perception" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 11008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711008

APA StyleQi, A., Ji, Z., Gong, Y., Yang, B., & Sun, Y. (2022). The Impact of the Gain-Loss Frame on College Students’ Willingness to Participate in the Individual Low-Carbon Behavior Rewarding System (ILBRS): The Mediating Role of Environmental Risk Perception. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711008