Transcriptomics Analysis of the Toxicological Impact of Enrofloxacin in an Aquatic Environment on the Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Sampling

2.2. Histopathological Analysis of the Hepatopancreas

2.3. Total RNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.4. De Novo Transcriptome Assembly

2.5. Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) Analysis

2.6. Enzymatic Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

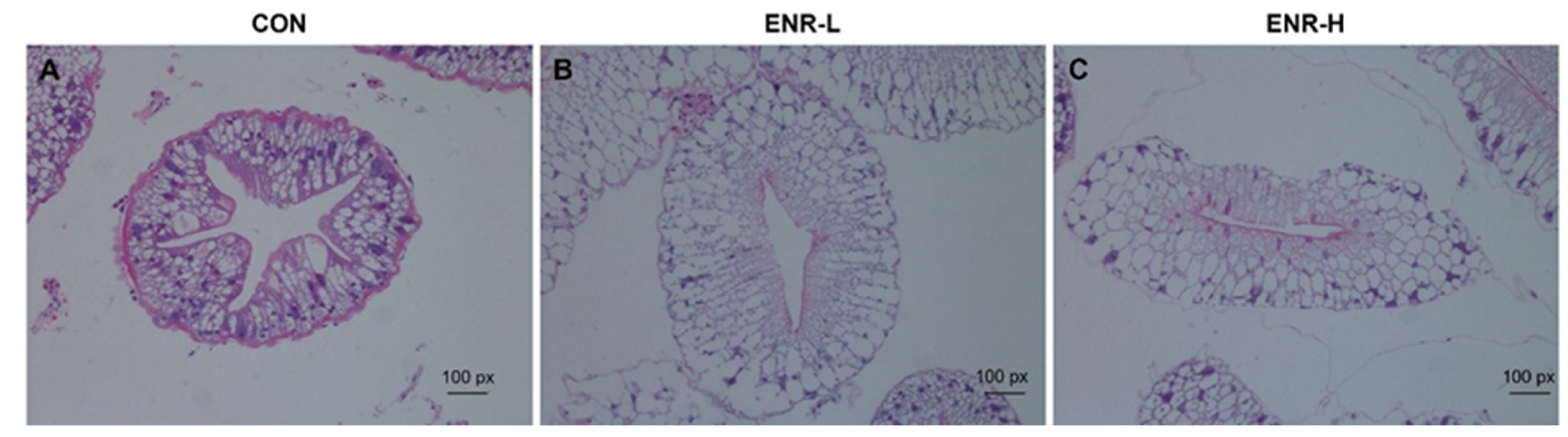

3.1. Enrofloxacin Residues Induced Hepatopancreas Injury in E. sinensis

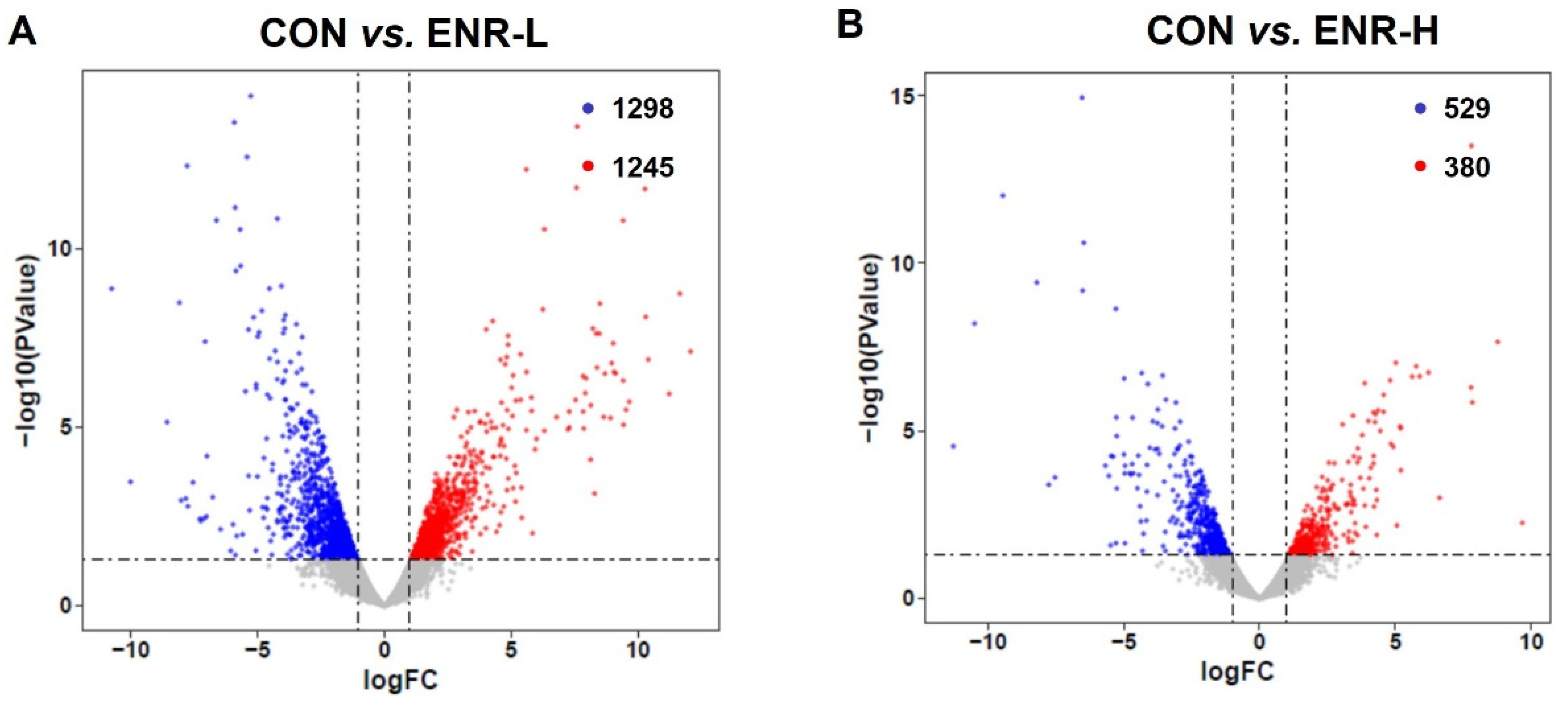

3.2. Enrofloxacin Residues Led to Multiple Gene Expression Disorders in the Hepatopancreases of Crabs

3.3. GO Analysis of DEGs Found Significant Enrichment of Biological Processes Related to Metabolism Process in Enrofloxacin Residue Groups

3.4. Molecular Function in GO Analysis of DEGs

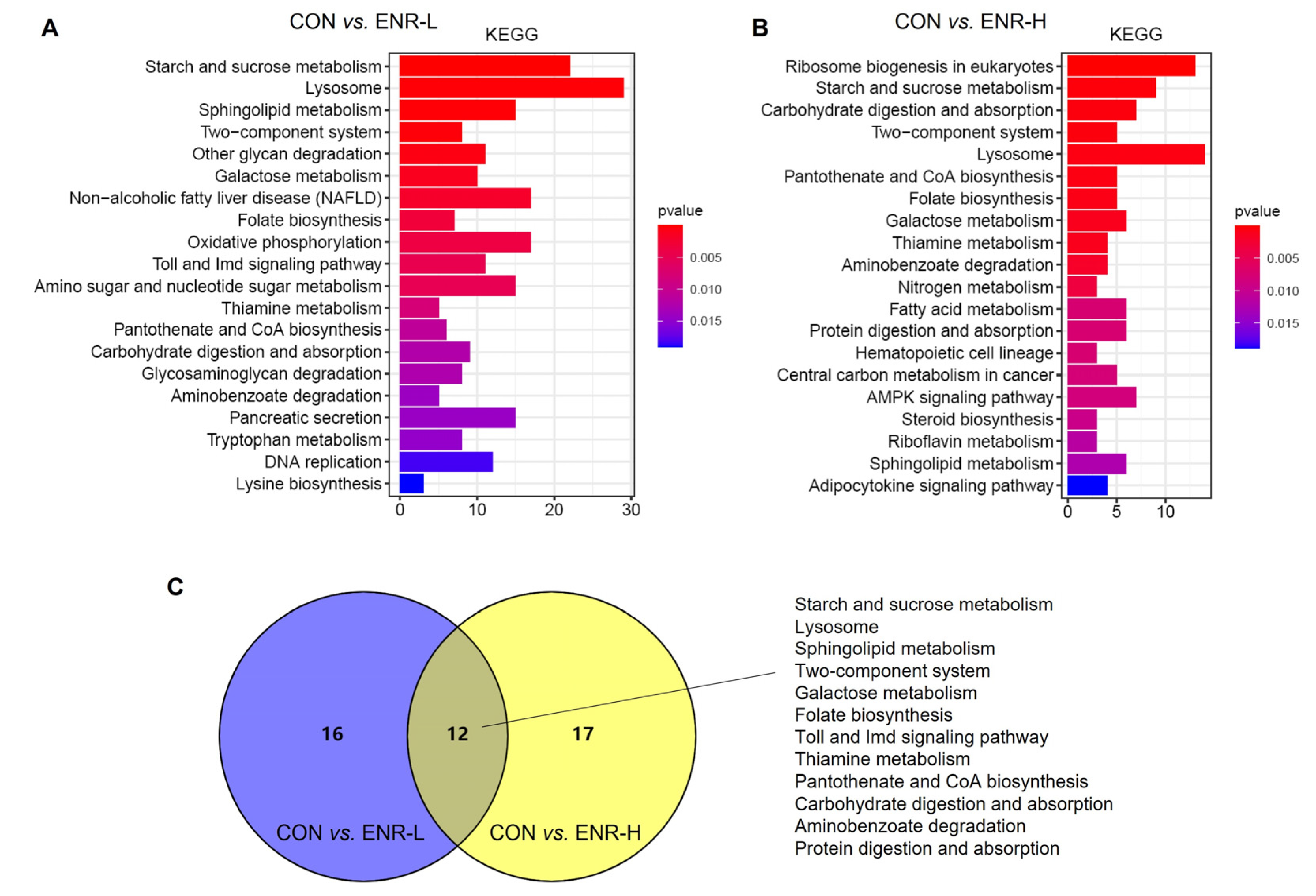

3.5. Results of KEGG Analysis of DEGs

3.6. Enrofloxacin Residues Led to Immune System and Metabolic Process Disorders in the Hepatopancreases of Chinese Mitten Crabs

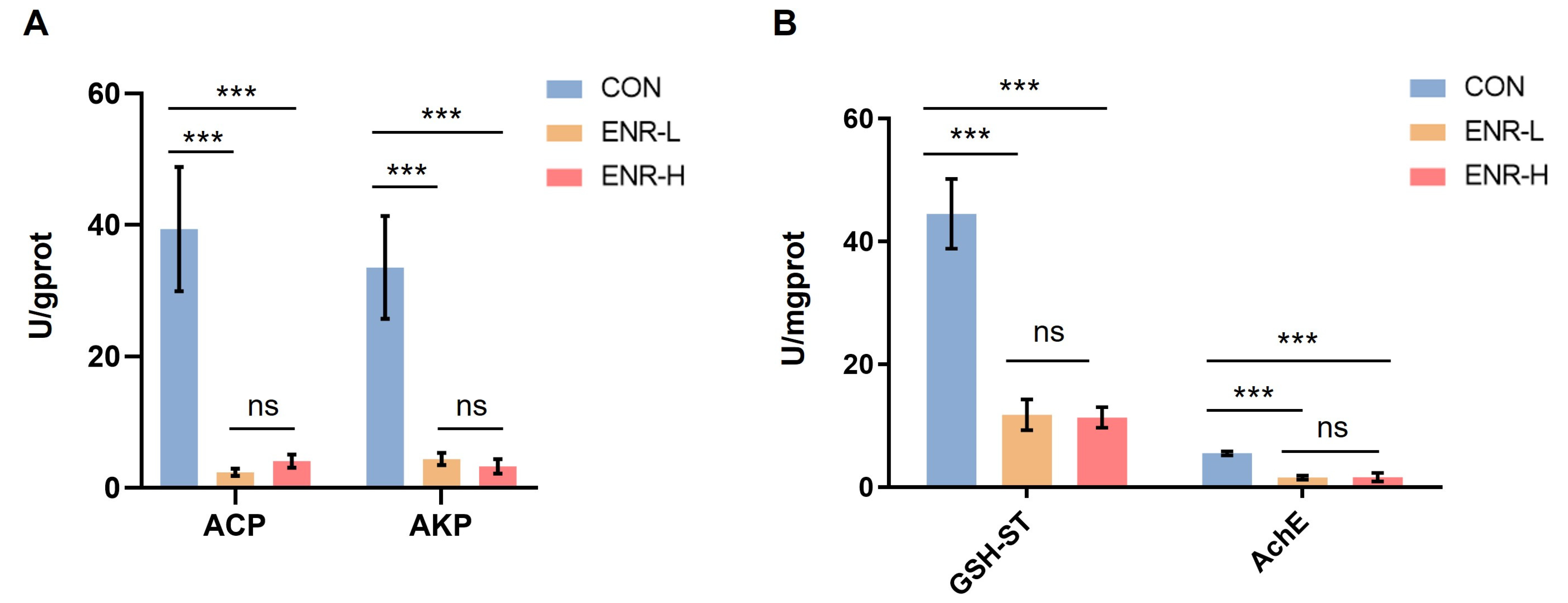

3.7. Immune Responses and Metabolic Enzymatic Activities following Exposure to Enrofloxacin Residues

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, C.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, L.; Fan, L.; Wu, W.; Meng, S.; Hu, G.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Dietary risk ranking for residual antibiotics in cultured aquatic products around Tai Lake, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 144, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liangwei, X.; Zhen, L.; Keyi, M. Analysis of genetic diversity in cultured populations of the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) by microsatellite markers. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2012, 35, 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L.; Huang, Z.; Fan, L.; Hu, G.; Qiu, L.; Song, C.; Chen, J. Health risks associated with sulfonamide and quinolone residues in cultured Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) in China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 165, 112184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koc, F.; Uney, K.; Atamanalp, M.; Tumer, I.; Kaban, G. Pharmacokinetic disposition of enrofloxacin in brown trout (Salmo trutta fario) after oral and intravenous administrations. Aquaculture 2009, 295, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, A.M.; Farmer, B.D.; Hawke, J.P. Improved Method for Determining Antibiotic Susceptibility of Flavobacterium columnareIsolates by Broth Microdilution. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 2008, 20, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.; McDermott, P.; Walker, R. Pharmacology of the fluoroquinolones: A perspective for the use in domestic animals. Vet. J. 2006, 172, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Meng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Huang, C. Pharmaco kinetics and tissue distribution of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in the Chinese mitten-handed crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 358, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-T.; Zhang, G.-D.; Sun, R.-Y.; Zhou, S.; Dong, J.; Yang, Y.-B.; Yang, Q.-H.; Xu, N.; Ai, X.-H. Determination of pharmacokinetic parameters and tissue distribution characters of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in Procambarus clarkii after two routes of administration. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 22, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, G.; Meng, Y.; Xu, X. Study on the pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin in the Chinese mitten-handed crab, Eriocheir sinensis, after different administration regimes. Aquac. Res. 2008, 39, 1210–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Yang, X.-L.; Zheng, Z.-L.; Yu, W.-J.; Hu, K.; Yu, H.-J. Pharmacokinetics and the active metabolite of enrofloxacin in Chinese mitten-handed crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquaculture 2006, 260, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wei, Y.; Sun, J.; Hu, K.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, R.; Yang, X. Effect of lactic acid on enrofloxacin pharmacokinetics in Eriocheir sinensis(Chinese mitten crab). Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A.; Lewbart, G.A.; Hancock-Ronemus, A.; Papich, M.G. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in Atlantic horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) after single injection. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 41, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, W.-H.; Zhou, S.; Yu, H.-J.; Hu, L.-L.; Zhou, K.; Liang, S.-C. Phannacokinetics and tissue distribution of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in Scylla serrata following oral gavage at two salinities. Aquaculture 2007, 272, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, M.; Castillo, M.; Marti, P.; Althaus, R.L.; Molina, M.P. Effect of Heating on the Stability of Quinolones in Milk. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 5427–5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ai, X.; Sun, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Dong, J.; Yang, Q. Residue, biotransformation, risk assessment and withdrawal time of enrofloxacin in red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii). Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.P.; Li, J.; Li, J.T.; Liu, P.; Chang, Z.Q.; Nie, G.X. Accumulation and elimination of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in the ridgetail white prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda following medicated feed and bath administration. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 37, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phu, P.M.; Douny, C.; Scippo, M.-L.; De Pauw, E.; Thinh, N.Q.; Huong, D.T.T.; Phuoc, V.H.; Phuong, N.T.; Dalsgaard, A. Elimination of enrofloxacin in striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) following on-farm treatment. Aquaculture 2015, 438, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.; Sun, J.; Fang, S.; Wei, Y.; Zheng, R.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, K. Effects of lactic acid on drug-metabolizing enzymes in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sisnensis) after oral enrofloxacin. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 223, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Gupta, S. The multifaceted role of glutathione S-transferases in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018, 433, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, B.; Feng, X.; Singh, B.R. Marine Glutathione S-Transferases. Mar. Biotechnol. 2007, 9, 513–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Meng, S.; Xiang, M.; Ma, H. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in cell metabolism: Roles and mechanisms beyond gluconeogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2021, 53, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebert, D.W.; Wikvall, K.; Miller, W.L. Human cytochromes P450 in health and disease. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vogt, G. Functional cytology of the hepatopancreas of decapod crustaceans. J. Morphol. 2019, 280, 1405–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ried, C.; Wahl, C.; Miethke, T.; Wellnhofer, G.; Landgraf, C.; Schneider-Mergener, J.; Hoess, A. High Affinity Endotoxin-binding and Neutralizing Peptides Based on the Crystal Structure of Recombinant Limulus Anti-Lipopolysaccharide Factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 28120–28127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, S.; Huo, G.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, R.; Hua, C.; Zhou, F. Transcriptomics provides insights into toxicological effects and molecular mechanisms associated with the exposure of Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis, to dioxin. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2023, 139, 104540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, I.; Yoshida, Y.; Suda, M.; Minamino, T. DNA Damage Response and Metabolic Disease. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: New perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D353–D361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Zhang, T.; Liang, H.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Z.; Sun, W. Immune defense, detoxification, and metabolic changes in juvenile Eriocheir sinensis exposed to acute ammonia. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 240, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Yin, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Yang, X. Immune response to abamectin-induced oxidative stress in Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 188, 109889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Shpigelman, A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Montesano, D.; Barba, F.J. Direct and indirect measurements of enhanced phenolic bioavailability from litchi pericarp procyanidins by Lactobacillus casei-01. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2760–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yan, G.; Pan, C.; Zhang, J. Antioxidative status, immunological responses, and heat shock protein expression in hepatopancreas of Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis under the exposure of glyphosate. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 86, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, A.; Dodd, M.S. Metabolism. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 607–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heindel, J.J.; Blumberg, B.; Cave, M.; Machtinger, R.; Mantovani, A.; Mendez, M.A.; Nadal, A.; Palanza, P.; Panzica, G.; Sargis, R.; et al. Metabolism disrupting chemicals and metabolic disorders. Reprod. Toxicol. 2017, 68, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, X.; Tran, N.T.; Huang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Ma, H.; Li, S. Innate immune responses and metabolic alterations of mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) in response to Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 87, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z. Lipid metabolism disorders contribute to the pathogenesis of Hepatospora eriocheir in the crab Eriocheir sinensis. J. Fish Dis. 2021, 44, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, C.; Chen, F. Connections between metabolism and epigenetics in cancers. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 57, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulukutla, B.C.; Yongky, A.; Le, T.; Mashek, D.G.; Hu, W.-S. Regulation of Glucose Metabolism—A Perspective from Cell Bioprocessing. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Kumar, A.; Carmeliet, P. Metabolic Pathways Fueling the Endothelial Cell Drive. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019, 81, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L.; Soeters, M.R.; Wüst, R.C.I.; Houtkooper, R.H. Metabolic Flexibility as an Adaptation to Energy Resources and Requirements in Health and Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ballabio, A.; Bonifacino, J.S. Lysosomes as dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Perl, A. Metabolism as a Target for Modulation in Autoimmune Diseases. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, G.; Khan, D.H.; Lee, J.B.; Mirali, S.; Zhang, L.; Schimmer, A.D. Mitochondrial and Metabolic Pathways Regulate Nuclear Gene Expression to Control Differentiation, Stem Cell Function, and Immune Response in Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 1052–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, H. Metabolic pathways and metabolites shaping innate immunity. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 39, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Shen, J.-L.; Wang, T.; Yang, B.; Liang, C.-S.; Jiang, H.-F.; Wang, G.-X. Ophiopogon japonicus inhibits white spot syndrome virus proliferation in vivo and enhances immune response in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 119, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Jin, J.; Jeon, S.; Moon, S.H.; Park, M.Y.; Yum, D.-Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, J.-E.; Park, M.H.; Kim, E.-J.; et al. SOD1 suppresses pro-inflammatory immune responses by protecting against oxidative stress in colitis. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, C. From oxidative stress to inflammation: Redox balance and immune system. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4240–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deretic, V. Autophagy in inflammation, infection, and immunometabolism. Immunity 2021, 54, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Mizushima, N.; Virgin, H.W. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 2011, 469, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deretic, V.; Saitoh, T.; Akira, S. Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ataş, H.; Gönül, M.; Öztürk, Y.; Kavutçu, M. Ischemic modified albumin as a new biomarker in predicting of oxidative stress in alopecia areata. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 49, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CON 1 vs. ENR-L 2 | CON vs. ENR-H 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Term | Count | p Value | Term | Count | p Value |

| carbohydrate metabolic process | 37 | 0.000136285 | carbohydrate metabolic process | 17 | 0.000478166 |

| obsolete electron transport | 27 | 0.004245120 | purine nucleobase metabolic process | 13 | 0.029346042 |

| tyrosine metabolic process | 13 | 0.001825573 | transcription and DNA-templated | 12 | 0.029356640 |

| regulation of GTPase activity | 13 | 0.005738756 | mRNA processing | 8 | 0.032290906 |

| tRNA aminoacylation for protein translation | 12 | 0.005255766 | viral release from host cell | 5 | 0.020254351 |

| glycerolipid metabolic process | 9 | 0.006135912 | tricarboxylic acid cycle | 3 | 0.008758657 |

| tryptophan metabolic process | 8 | 0.004595175 | pentose phosphate shunt | 3 | 0.021326841 |

| tRNA aminoacylation | 6 | 0.004389519 | regulation of blood coagulation | 2 | 0.004063707 |

| positive regulation of voltage-gated potassium channel activity | 5 | 0.001854393 | positive regulation of release of cytochrome c from mitochondria | 2 | 0.004063707 |

| regulation of synaptic transmission and cholinergic | 5 | 0.001854393 | tryptophan catabolic process to kynurenine | 2 | 0.006012747 |

| sleep | 5 | 0.001854393 | viral DNA genome replication | 2 | 0.006012747 |

| obsolete peroxidase reaction | 5 | 0.006743223 | amino sugar metabolic process | 2 | 0.008303677 |

| response to oxidative stress | 5 | 0.008306801 | intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway | 2 | 0.010921666 |

| chlorophyll catabolic process | 4 | 0.000717921 | endoplasmic reticulum inheritance | 2 | 0.013852347 |

| lysine biosynthetic process | 4 | 0.007702752 | gene silencing by RNA | 2 | 0.017081801 |

| carboxylic acid metabolic process | 4 | 0.012737180 | cell wall macromolecule catabolic process | 2 | 0.028430117 |

| styrene catabolic process | 3 | 0.003663577 | histidine biosynthetic process | 2 | 0.028430117 |

| regulation of autophagy | 3 | 0.006128731 | protein import into mitochondrial matrix | 2 | 0.032724060 |

| photosystem II stabilization | 3 | 0.009375217 | 7-methylguanosine RNA capping | 2 | 0.037253517 |

| methane metabolic process | 3 | 0.013447069 | RNA methylation | 2 | 0.037253517 |

| CON 1 vs. ENR-L 2 | CON vs. ENR-H 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| logFC | p Value | logFC | p Value | |

| Immune system | ||||

| alkaline phosphatase | −5.909012989 | 2.99 × 10−14 | −1.36058962 | 3.84 × 10−2 |

| dual oxidase 1 | −3.065045953 | 3.06 × 10−3 | −2.19026803 | 1.42 × 10−2 |

| NF-kappa B inhibitor alpha | 1.680036355 | 1.13 × 10−2 | 1.668237232 | 2.98 × 10−2 |

| metabolic process | ||||

| venom phosphodiesterase 2-like | −2.154713643 | 1.46 × 10−4 | −1.70584579 | 5.71 × 10−3 |

| beta 1,4-endoglucanase | −4.572645684 | 6.59 × 10−3 | −2.81828784 | 1.40 × 10−2 |

| alpha-amylase | −1.803435554 | 1.97 × 10−2 | −1.50174728 | 1.70 × 10−2 |

| arylsulfatase A-like | −3.900096603 | 7.40 × 10−9 | −1.42018217 | 1.51 × 10−2 |

| ecdysteroid receptor (EcR) gene | −2.393264135 | 1.87 × 10−5 | −2.0989689 | 2.25 × 10−4 |

| beta-galactosidase-like | −2.452835189 | 4.92 × 10−5 | −1.93785202 | 8.92 × 10−4 |

| pantothenate kinase 3-like | −2.018241358 | 7.46 × 10−3 | −1.51740929 | 3.45 × 10−2 |

| carboxypeptidase B-like | −3.554127549 | 1.86 × 10−4 | −3.08832125 | 2.19 × 10−4 |

| trypsin-like serine proteinase | −4.213806456 | 4.03 × 10−3 | −3.9272743 | 5.16 × 10−6 |

| chitinase 3 | −2.837019698 | 2.05 × 10−3 | −1.33310288 | 4.96 × 10−2 |

| juvenile hormone esterase-like carboxylesterase 1 | −2.794416003 | 4.66 × 10−2 | −1.6048277 | 1.09 × 10−2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huo, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Hua, C.; Li, S.; Zhou, F. Transcriptomics Analysis of the Toxicological Impact of Enrofloxacin in an Aquatic Environment on the Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031836

Wang Q, Xu Z, Wang Y, Huo G, Zhang X, Li J, Hua C, Li S, Zhou F. Transcriptomics Analysis of the Toxicological Impact of Enrofloxacin in an Aquatic Environment on the Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031836

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qiaona, Ziling Xu, Ying Wang, Guangming Huo, Xing Zhang, Jianmei Li, Chun Hua, Shengjie Li, and Feng Zhou. 2023. "Transcriptomics Analysis of the Toxicological Impact of Enrofloxacin in an Aquatic Environment on the Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031836